Bladder and Urethra

The bladder and upper urethra are composed of bundles of smooth muscle fibers arranged in a reticular lattice, the outermost bundles being more circular and the inner bundles more longitudinal in orientation at the bladder neck.1 The smooth muscle bundles blend into the striated muscle of the external urethral sphincter, which is derived from the pelvic diaphragm. The bladder is lined by transitional epithelium, which is sensitive to irritants such as bacterial toxins and various urinary crystals. The urethra and trigone are especially sensitive, and the presence of any irritant in these areas can create significant discomfort.

Proper function of the lower urinary tract depends on intact autonomic and somatic nervous innervation. The detrusor muscle of the bladder is innervated by both sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers. Storage functions are mediated by the sympathetic component, which arises from spinal levels T10–L1. The chemical mediator of this process is norepinephrine, which acts on β-adrenergic receptors in the fundus of the bladder and causes muscle relaxation for low-pressure storage of urine. The same sympathetic stimulus acts on the β-adrenergic receptors of the trigone, bladder neck, and proximal urethra to increase internal sphincter activity and promote continence during urine storage by maintaining outlet resistance. The external urinary sphincter, innervated by the pudendal nerve, progressively increases its tone as the bladder fills, providing additional resistance. As the child develops, the external sphincter may be consciously contracted at times of urgency or stress to prevent the unwanted passage of urine. Properly coordinated function of the external urinary sphincter relies on an intact sacral reflex arc which should be well developed in normal infants, but is variably functional in infants with spinal cord abnormalities or pelvic lesions.2,3

Spinal pathways connect the sacral micturition center with three areas in the brain stem, collectively referred to as the pontine micturition center.4 This center functions to inhibit urination during storage and to produce external sphincter relaxation during the voiding phase. Above this level are areas of cerebral cortex which oversee and modulate the autonomic process. It is the mature, integrated function of all these components that produces urinary continence.

Toilet training is, in large part, a learned phenomenon. It requires adequate recognition by the brain that micturition would be socially unacceptable in a given situation. With maturation, the bladder gains capacity, allowing for longer intervals between voiding. The approximate bladder volume in ounces may be estimated in a child as age in years plus 2. It may also be calculated by a more precise formula if needed.5 Infants void 20 times per day, which decreases to about ten times per day by age 3 years.6 The child also learns to resist the urge to void by voluntary contraction of the external sphincter until the detrusor contraction passes and the bladder once again relaxes. Thus, toilet training depends on the development of voluntary detrusor sphincter dyssynergia (DSD), which at times is dysfunctional.7 Finally, full bladder control relies on the child developing volitional control over the spinal micturition reflex to be able to initiate or inhibit detrusor contractions. Most children attain day and night continence by 4 years of age.

Childhood Incontinence

Incontinence is the term used for the unintentional loss of urine after toilet training is achieved. The following definitions are clinically useful:8

Enuresis or nocturnal enuresis: intermittent incontinence while sleeping

Primary nocturnal enuresis: never been continent at night

Secondary nocturnal enuresis: nighttime incontinence following a dry period of at least 6 months.

Daytime incontinence: daytime wetting after toilet training

Stress incontinence: urine leakage due to physically stressful activities such as coughing.

Urge incontinence: unintentional loss of urine when bladder urgency occurs.

The discussion of incontinence is divided into sections on nocturnal enuresis and daytime incontinence, realizing that some children have both. The current recommendation for children with nocturnal enuresis and daytime incontinence is to focus on daytime treatment first followed by nocturnal enuresis therapy.

Nocturnal Enuresis

About 15–20% of children at 5 years of age continue to have bed wetting.9–13 As so many children still wet at night before this age, it is considered within the range of normal and not termed nocturnal enuresis. After age 5, night wetting resolves at the rate of about 15% each year. By age 15 years, it has resolved in 99% of children.13

Etiology

Genetic.

Family history is significant. If both the parents had enuresis, 77% of their offspring will as well. If one parent was affected, 44% of the offspring are affected. If neither parent has a history, only 15% of their children have this problem.12,14

Developmental.

As children grow, bladder capacity increases significantly each year at a proportion greater than urine volume produced.11,15,16 Volitional control over bladder and sphincter also may mature at variable rates and may be related to subtle delays in perceptual abilities or fine motor skills.17

Urodynamic.

Studies show that enuretic episodes occur when the bladder is full, and they simulate normal awake voiding.16 Although nocturnal enuretic patients have more nighttime unstable bladder contractions, these are at low pressure and do not cause leakage.

Sleep Disorders.

Parents of children with nocturnal enuresis are generally convinced that these children sleep deeply and are difficult to arouse. However, this is probably not true. Enuretic patients sleep no more deeply than age-matched controls, wet in all stages of sleep, and show no different awakening patterns. Wetting episodes occur as the bladder fills throughout the night.18

Antidiuretic Hormone.

Antidiuretic hormone (ADH) is released from the pituitary in a circadian rhythm so that levels are higher at night and thus diminish urine output. Some children may undersecrete ADH at night resulting in bed wetting.19–22 Although some patients follow this pattern, others do not; the altered circadian patterns appear to normalize with maturation.23

Treatment

Enuretic Alarms.

Wetting alarms are devices that fit in the underwear of the patients. When moistened, an alarm is sounded. This type of conditioning therapy requires a motivated patient and parents. A variety of products are available with either an audio alarm, a vibrating alarm, or both. In our experience, the best alarm is simply one that is easy to set up and is able to wake the child. The parent may need to help arouse the child, take him or her to the bathroom, and reset the alarm. This may occur multiple times each night, particularly at the onset of therapy. In two studies, wetting alarms were shown to give the best long-term results when compared with other treatments.24,25 The length of treatment to achieve dryness varied between 18 nights and 2.5 months. Relapse may occur in 20–30% of treated children, but re-treatment can be successful.25

Medications.

Imipramine, a tricyclic antidepressant, has been used for many years. The exact mechanism of action is unknown. Initial success has been reported in the 50% range. However, a recent review showed only a 20% success with a relapse rate of 96%.26 Clinical practice reveals that the longer the initial treatment, the more benefit before the effect wanes. It is suggested that the medication be weaned slowly rather than stopped abruptly.

Side effects include anxiety, insomnia, dry mouth, nausea, and personality changes. An overdose can cause fatal cardiac arrhythmias.27 Therefore, medication safety in the home is important. Imipramine may improve response rates to the enuretic alarm.

Desmopressin is an analog of ADH that mimics its urine-concentrating activity without the vasopressor effect.28 The effect is dose dependent, usually requiring 20– 40 µg/day for success.

Complete dryness rates may be highest in patients with a strong family history of success. Efficacy and safety have been demonstrated in a number of studies, but long-term success remains lower than with alarm systems.28–30 Desmopressin may occasionally have side effects, including electrolyte changes, nasal irritation, and headaches. Desmopressin is available as a nasal spray. However, this route is not approved for treating nocturnal enuresis due to a higher incidence of hyponatremia. Parents should be warned to avoid over-hydration to prevent this side effect.

Oxybutynin is the most common drug used for enuresis. It is effective when day and nighttime wetting occur in the same patient, but has no benefit over placebo when nighttime wetting is the only symptom.31

Daytime Incontinence

The patient history is of paramount importance in sorting out the various categories of daytime incontinence.32,33 The physical examination and evaluation should always assess for an abdominal mass or tenderness, distended bladder, normal genitalia, signs of spina bifida occulta, perineal sensation, sacral reflexes, gait, lower extremity reflexes, and urinalysis. Radiographic evaluation, usually voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) and renal ultrasonography (US), are important in patients with UTI or complex incontinence patterns.

Bladder Instability

Bladder instability is by far the most common diagnosis in children with persistent daytime wetting.34 These children are usually toilet trained, but later develop increasing ‘accidents’ associated with urgency. They describe not knowing that the bladder contraction was coming. They dash to the bathroom or try to ‘hold it in.’ Boys grab and compress the penis, and girls often cross their legs and dance around or squat with the heel compressed over the perineum (Vincent curtsy). In our experience, children with hyperactivity disorders or a willful disposition appear prone to this pattern.

Treatment.

Effective treatment rests on managing all aspects of this condition simultaneously. Constipation is treated with fiber or laxatives, and mineral oil after initial bowel clean-out. Recurring UTIs are managed with prophylactic antibiotics. Bladder instability is treated with timed voiding at frequent intervals (an alarm watch for the child is helpful) and anticholinergics such as oxybutynin or tolterodine.35–37

Biofeedback has gained in popularity for treatment of the VD. Electrodes placed on the perineum near the genitourinary diaphragm can be attached to monitors, an audio signal, or a computer display so the children can learn to relax their external sphincter voluntarily, resulting in better voiding coordination.38–40 The process typically requires four to eight weekly visits, with follow-up as needed.

Neuromodulation has been used mainly in adults who have a refractory overactive bladder; however, there has been recent use in children. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) has been popular because of its non-invasive nature, though it requires numerous sessions. The TENS unit is thought to inhibit bladder activity via the pudendal–pelvic nerve reflex. Initial studies show promise with improvements ranging from 73–100% in small series.41,42

Initial success with any treatment is often followed by later relapse. If initial treatment is unsuccessful, it may be successful if re-tried later. Patients older than 8 years who fail treatment should be considered for urodynamic testing. Secondary VUR usually resolves (80%) as bladder function improves.43 The unstable bladder of childhood is usually age limited.

Isolated Frequency Syndrome

A separate, and much less common, group of children present with acute onset of urinary frequency. They appear healthy, are normal on examination, and have normal urinalysis and culture. They do not have true urgency or any wetting, but feel that they must urinate frequently, sometimes every 5 to 10 minutes. They void a very small amount each time. Most sleep through the night and void a large amount on awakening. The pattern may come and go over weeks or months.

Infrequent Voider/Underactive Bladder

On the other end of the voiding spectrum are those children who void only once or twice daily and may not urinate until afternoon after waking in the morning.44 These children have developed urinary retentive behavior without any bladder instability and have dilated, high-capacity, low-pressure bladders.45 Some show an aversion to bathrooms or exhibit excessive neatness, whereas many others appear reasonably adjusted. They may be somewhat prone to UTI and stress incontinence.

Continuous Incontinence

Hinman Syndrome

A small number of children demonstrate persistent incontinence, repeated febrile UTI, VUR, high bladder storage pressures, and very poor emptying.46 This appears to be a deeply ingrained ‘learned’ disorder of severe voluntary DSD. In these patients, the urinary tract has the appearance of a patient with a neurogenic bladder. There is hydronephrosis, a trabeculated bladder, reflux, and sometimes progressive loss of renal function (Fig. 56–1).

FIGURE 56-1 (A) This cystogram shows the typical findings in a patient with Hinman syndrome: trabeculated bladder and severe reflux. (B) This voiding study in the same patient demonstrates dilation of the posterior urethra (asterisk) as a result of chronic contraction of the external sphincter during voiding.

Aggressive therapy with prophylactic antibiotics, anticholinergics, alpha blockers, urodynamic biofeedback training, timed voiding, or clean intermittent catheterization (CIC) may be required.47,48 Some recalcitrant cases may require bladder diversion or augmentation to avoid renal failure. As with many ‘functional’ disorders, the severity of Hinman syndrome tends to wane with maturation, but progressive deterioration may not permit the surgeon to wait.

Neurogenic Bladder

True neurogenic dysfunction of the bladder in childhood results from acquired or congenital lesions that affect bladder innervation. Acquired lesions may occur from trauma to the brain, spinal cord, or pelvic nerves, or as a result of tumor, infection, or vascular lesions affecting these same structures. Congenital lesions include spina bifida and other neural tube defects (most common), degenerative neuromuscular disorders, cerebral palsy, tethered cord, sacral agenesis, and other causes.49

The most practical way to classify neurogenic bladder abnormalities is by a simple functional system: failure to store, failure to empty, or a combination of both.50 Failure to store urine may be caused by the detrusor muscle itself or by the bladder outlet. Detrusor hyperactivity or poor compliance causes elevated bladder pressures and incontinence on this basis. An incompetent bladder neck or urethral sphincter mechanism can be the outlet cause of failure to store urine even if storage pressures are reasonable. Failure to empty can be secondary to the hypotonic, neurogenic bladder which may not generate enough pressure to empty, or increased outlet resistance secondary to striated or smooth muscle sphincter dyssynergia. This classification helps to base treatment on urodynamic data.

Myelomeningocele

The most common cause of neurogenic bladder in childhood are neural tube defects, which range from occult spinal dysraphism to myelomeningocele.51,52 Myelomeningocele is most common, reported in about 1 in 1,000 live births with notable geographic variations.53,54 The etiology is multifactorial, with a clear familial association (2–5% sibling risk) and evidence that periconceptual folic acid supplementation (0.4 mg/day) reduces the risk by 60–80%.55 Improved treatment for the neurosurgical aspects of this lesion since the late 1970s has increased the survival rate. Ninety per cent of newborns with myelomeningocele have normal upper tracts. However, if the bladder is not treated, at least half of these patients show signs of upper tract deterioration or reflux within five years.56 Therefore, early urologic evaluation and continued follow-up is critical in these patients.57,58

Evaluation of the Newborn with Myelomeningocele

Fetal closure of myelomeningocele has been evaluated in a multi-institutional randomized controlled trial.59 The results showed ventriculoperitoneal shunting was reduced by 50% at 12 months of age as was improved psychomotor development and motor function in children who underwent fetal repair. However, fetal intervention was associated with increased maternal and fetal risks. Unfortunately, there is still limited long-term data to demonstrate improved bowel or bladder function for these patients.60

Generally, the newborn with myelomeningocele has had a thorough neurologic assessment, closure of the lumbar defect, and possibly even ventriculoperitoneal shunting before any evaluation of the urinary tract. The level of the bony defect does not predict the functional cord level because the spinal cord lesion may be partial and patchy. Before discharge, renal and bladder ultrasound should be performed to evaluate parenchymal quality, the presence of hydronephrosis, and the size and function of the bladder. A small number of these patients have an abnormal ultrasound. In such cases, VCUG and possibly a renal scan should be performed. If the ultrasound is normal, other studies can probably be delayed a few months. About 3–5% of these patients have VUR in the newborn period. The incidence of VUR increases with time, particularly in patients with untreated DSD or detrusor hyperactivity.49 Antibiotic prophylaxis is important and serum creatinine should be followed during the initial hospitalization. After closure of the defect, postvoid residuals should be measured before discharge from the hospital. CIC is begun if the residual urine is consistently greater than 15 ml. Crede’s maneuver should be avoided because it is ineffective in emptying the bladder and magnifies the detrimental effects of high intravesical pressure if DSD or VUR are present.

Newborn urodynamic (UD) evaluation has been shown to have prognostic value in determining bladder function. Bladder pressures higher than 40 cmH2O at the point of urinary leakage and those with DSD are much more likely to show upper tract deterioration or VUR.58 Other factors known to indicate bladder ‘hostility’ include hyperreflexic contractions and high storage pressures.61 Therefore, early UD evaluation (typically by 12 weeks of age) is essential to determine the frequency of follow-up studies and the timing of initiation of bladder therapy programs.

Childhood Management

Periodic reassessment of the anatomy and function of the urinary tract in patients with a neurogenic bladder is key because the clinical and UD picture may change with growth and spinal cord tethering.62 Initiation of a bladder management program is generally undertaken when there is worsening bladder ‘hostility,’ VUR, hydronephrosis, or infection. If the urinary tract is stable, such management may be delayed until social continence is desired.

The cornerstone of treatment programs for neurogenic bladder is CIC. Popularized in the early 1970s, CIC has revolutionized the treatment program for these children.62 The purpose of CIC is to provide periodic low-pressure emptying of the bladder, which can prevent or improve deterioration of the upper tracts.63,64 In younger children, this task is performed by the caretaker. As children become older and more responsible, they can assume this task.

CIC is associated with a high incidence of bacteriuria, varying greatly in different series.65,66 Bacteriuria is eventually found at least 60% of cases within one year, often with one or two symptomatic episodes per year.67 In patients with no VUR and with normal intravesical pressure, asymptomatic bacteriuria appears to have little clinical significance. However, in patients with high storage pressures and/or VUR, the likelihood for upper tract infection increases significantly.67 Infection with urea-splitting organisms (usually Proteus species) increases the potential for struvite stone formation.

Pharmacologic therapy for neurogenic bladder coupled with CIC is aimed at decreasing the pressures in the hypertonic, noncompliant bladder or increasing bladder outlet resistance to aid in obtaining continence. Anticholinergic drugs, such as oxybutynin, propantheline, or tolterodine, can be used to lower bladder storage pressures by blocking hypertonic detrusor activity.68 Imipramine may also be useful alone or in combination with the anticholinergic agents because it can both relax the detrusor and tighten the outlet. Inadequate vesical outlet resistance may also respond to α-adrenergic medications, such as pseudoephedrine. Often, the combination of anticholinergics, α-agonists, and CIC is required to gain adequate continence. Side effects of the anticholinergics may sometimes limit their use. Tolterodine and extended release oxybutynin are purported to cause fewer side effects than other anticholinergics. Instillation of oxybutynin directly into the bladder can lessen the side effects and still maintain a therapeutic response. Also, the recently developed oxybutynin cutaneous patch may offer improved treatment for these patients.69 Finally, cystoscopic injection of botulinum toxin type A received USA Food and Drug Administration approval in 2011 for detrusor overactivity in adults. Botox therapy has been applied to children with neurogenic bladder in an effort to decrease bladder pressures and increase compliance; however, data remains limited to small case series in children.70,71 The effects of the injection are short term and repeated injections are required.

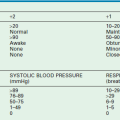

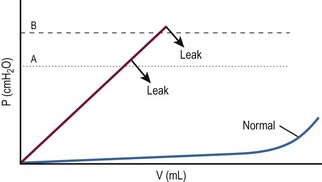

Urodynamic assessment may be elaborate in certain situations, but is usually a simple measurement of the pressure–volume relationship of the bladder during filling. It is performed using a double-lumen catheter in the bladder and involves simultaneous assessment of external sphincter function with a perineal electrode. It also can be performed with contrast material and monitored fluoroscopically to add information. Evaluation of bladder compliance, hyperreflexic contractions, leak-point pressure, stress leak-point pressure, and sphincter dyssynergia can be extremely helpful in choosing among treatment options. Figure 56-2 demonstrates the effect of anticholinergics in shifting the pressure–volume curve to the right and thus permitting the bladder to store more urine at any given pressure. Figure 56-3 shows the effect of α-adrenergic agonists on raising the leak-point pressure and thus improving continence.

FIGURE 56-2 Bladder filling pressure-volume curve in a patient with a neurogenic bladder. Note the shift of the curve to the right (A to B) when anticholinergics relax the detrusor, allowing lower pressure at any given volume.

FIGURE 56-3 Bladder filling pressure-volume curve demonstrating a higher leak-point pressure (from A to B), sometimes achieved with α-adrenergic agents such as pseudoephedrine and imipramine. The effect is to decrease incontinence at lower pressures.

In children with high bladder storage pressures and deterioration of the upper tracts that cannot be managed by CIC and pharmacologic therapy, temporary diversion with cutaneous vesicostomy may be necessary.72,73 Protection of the upper urinary tracts from high bladder pressures is thus accomplished until such time that other treatments can be effective. We reserve this treatment for infants who have serious deterioration of the upper tract and those who, for social, medical, or anatomic reasons, cannot be managed with the other aforementioned forms of medical treatment. As an alternative, some advocate urethral dilation in girls to diminish the leak-point pressure. Surprisingly, relatively long-term benefit has been found.74

Surgical Treatment

Treatment of VUR in the neurogenic bladder is much the same as that for the normal bladder.75 It is imperative that the bladder is adequately treated for poor compliance and hyperreflexia (CIC and anticholinergics) before and after operation to diminish the risk of recurrence.76

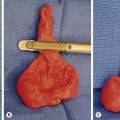

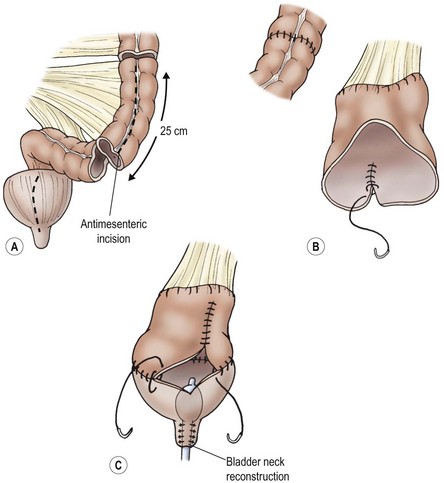

In some cases, bladder augmentation may be required. Bladder augmentation is designed to create a reservoir with good compliance and adequate capacity to store urine until it can be emptied by CIC at socially appropriate intervals. Detubularized segments of large or small bowel employed as a patch on the widely opened bladder (enterocystoplasty) are current popular techniques for augmentation (Fig. 56-4). Another approach is gastrocystoplasty, which was used in the 1990s, but has since fallen out of favor.77,78 Its advantages over enterocystoplasty include a decrease in mucus formation, a possible decrease in infection, and maintenance of electrolyte balance in patients with renal insufficiency. Unfortunately, the hematuria–dysuria syndrome may affect up to one-third of patients, which limits its applicability.79 This problem and other complications of enterocystoplasty— metabolic derangements secondary to the absorption of urine by the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, excessive mucus production, stone formation and even an increased risk of bladder cancer—have led to a search for other approaches.

FIGURE 56-4 Bladder enlargement by enterocystoplasty (sigmoid) and bladder neck reconstruction. Enterocystoplasty enlarges the bladder nicely but has significant potential complications, including occasional perforation, which may present as acute abdominal pain.

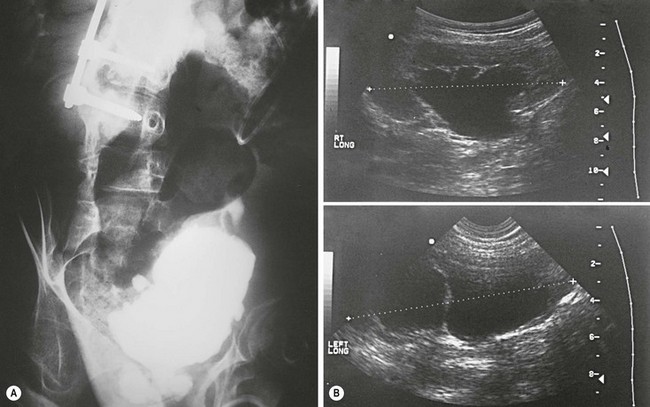

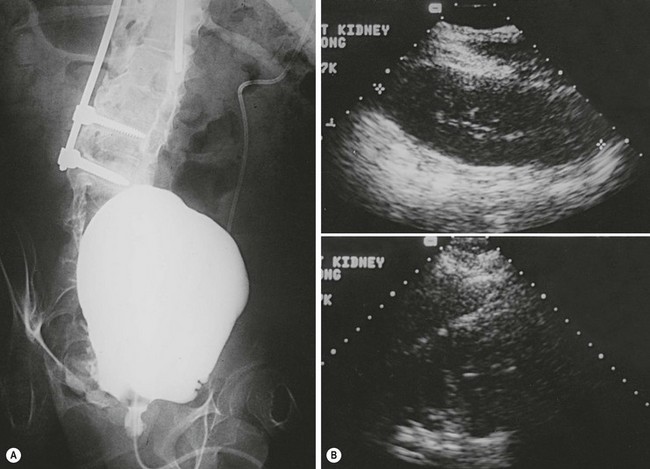

Bladder autoaugmentation or detrusorectomy is an alternative augmenting technique that may prove useful in selected patients (Figs 56-5 and 56-6).80 This approach involves removal of the detrusor muscle over the superior portion of the bladder, leaving the underlying bladder mucosa intact. This creates a large compliant surface, essentially a large diverticulum, which decreases bladder pressures and increases bladder capacity at the time of filling. The advantage of this technique is that the bladder epithelium is preserved and not replaced with gastrointestinal epithelium as in bowel augmentation, thus eliminating the problems associated with the secretory and absorptive functions of bowel mucosa. Long-term follow-up data on large numbers of children are lacking, but this technique appears to be a viable alternative for use in bladders with reasonable capacity and mainly poor compliance.81 The concept has been extended to create ‘composite’ bladders by placing demucosalized bowel or stomach patches over the urothelial bulge created in autoaugmentation.82,83 This concept of urothelial preservation during augmentation is carried forward by current innovative approaches to replace bladder wall with biodegradable scaffolds, typically seeded with urothelial and detrusor smooth muscle cells.84

FIGURE 56-5 (A) Radiographic and (B) ultrasonographic images of a patient with spina bifida showing a small, poorly compliant bladder and worsening hydronephrosis.

FIGURE 56-6 (A) Radiographic and (B) ultrasonographic images in the patient shown in Fig. 56-5 after bladder autoaugmentation, demonstrating improved bladder capacity and better compliance, which resulted in continence and diminished hydronephrosis.

Persistent incontinence, despite adequate treatment of the bladder to lower pressures and increase compliance, may require bladder outlet repair to increase resistance. The Young–Dees technique, which lengthens the urethra by infolding and tubularizing the trigone of the bladder, still has some advocates.85 Kropp’s procedure uses a tubularized anterior bladder strip reimplanted in the submucosa of the trigone to gain continence by a flap valve mechanism.86 Continence is commonly achieved, but catheterization is sometimes difficult.87 Pippi Salle’s procedure creates a similar (but easier to catheterize) flap valve by onlaying an anterior bladder wall flap onto a posterior incised strip up the middle of the trigone.88 Owing to the lack of a pop-off mechanism in both these procedures, if the bladder becomes overfilled, there is an increased potential for bladder rupture or for upper tract deterioration if high bladder pressure develops.

One of the more popular forms of increasing urethral resistance in a neurogenic bladder is by a bladder neck fascial sling.89–93 This procedure has many advocates and involves securing a rectus fascial strip (or other material) around the bladder neck and suspending it from the anterior rectus fascia or pubis. This elevates and compresses the urethra to increase outlet resistance.

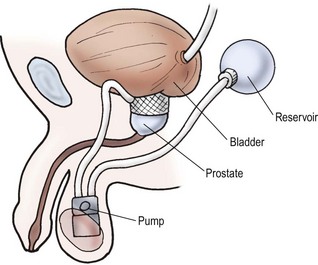

The artificial urinary sphincter is a fluid-filled pressurized cuff around the urethra or bladder neck, which can be deflated by a pump-reservoir device that permits the urethra to open and the bladder to drain (Fig. 56-7). The artificial urinary sphincter can also be used in higher-pressure bladders in conjunction with bladder augmentation.94 The main disadvantage is that it is a mechanical device that can erode into the urethra and malfunction over time. If the device is in situ long enough, it will eventually need revision. For this reason, we prefer to use autologous tissue techniques in children, when possible.

FIGURE 56-7 Typical artificial urinary sphincter. The scrotal pump moves fluid from the cuff to the reservoir to permit bladder emptying.

The periurethral injection of dextranomer/hyaluronic acid copolymer (Deflux™), Teflon, or polydimethysiloxane represents a simple, safe technique for enhancing urethral resistance in selected patients with poor intrinsic sphincter tone. It appears to be most applicable in patients requiring only a minimal increase in stress leak-point pressure. Long-term success is unlikely, and the usefulness of this approach in children is questionable.95,96

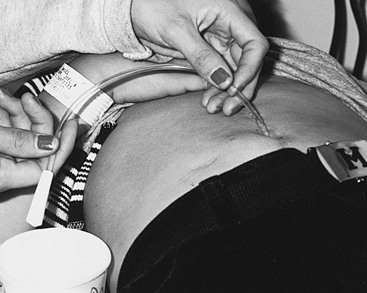

One beneficial adjunct in patients unable to self-catheterize their urethra (e.g., owing to spinal deformity, discomfort, or false passage) is the creation of a continent catheterizable stoma. This can be performed using the appendix or another small tubularized structure implanted into the bladder and anastomosed to the skin (Mitrofanoff principle).97,98 The implanted conduit can be hidden at the base of the umbilicus (Fig. 56-8)99 and CIC carried out using it. Alternatively, the appendix may be left in continuity with the cecum and brought to the skin as a catheterizable channel for irrigation/enemas for the neurogenic colon. In this circumstance, a small segment of ileum can be fashioned as a catheterizable Monti–Yang stoma.100 This concept has been a great adjunct to simplify catheterization for wheelchair-bound patients.

FIGURE 56-8 Umbilical positioning of an appendicovesicostomy permits easy access for clean intermittent catheterization. Some patients can remain in their wheelchairs and drain the bladder into the toilet through a catheter extender.

Cutaneous urinary diversion by ileal or colon conduit, or by cutaneous ureterostomy, is considered a last resort in these children. Long-term deterioration of the upper tracts is well documented in refluxing ileal conduits.101 Some protection of the upper tracts is afforded by a nonrefluxing colon conduit, but the success rate beyond two decades is uncertain.102 All reasonable efforts should be made to maintain ureteral drainage into the bladder.

Urethral Disorders

Urethral Prolapse

Urethral prolapse occurs in girls at a mean age of 5 years, with those of African descent being particularly prone to this problem.103 These patients present with dysuria, blood spotting on the underwear, and a bulging concentric purplish ring of prolapsed tissue at the urethral meatus (Fig. 56-9). Mild prolapse can be treated with an antibiotic ointment or estrogen cream applied to the area several times a day along with Sitz baths. There are times when a catheter is needed temporarily. In persistent cases, excision of the prolapsing tissue with reanastomosis of the skin edges is curative. Simple ligation of the prolapsing urethral epithelium over a Foley catheter is another described option. The prolapsed epithelium necroses and sloughs.

Meatal Stenosis

Meatal stenosis is the narrowing of the male urinary meatus following circumcision. It is thought to result from exposure and irritation of the meatus in the diaper.104,105 For reasons that are uncertain, the stenosis is always on the ventral aspect of the meatus, causing dorsal deflection of the urinary stream that is forceful. It is important for the physician to not only examine the meatus but also watch the child void. If the stream is not narrow in caliber or is not dorsally deflected, then the meatal stenosis is not significant enough to require treatment. Occasionally, voiding causes the web to tear, resulting in dysuria or a drop of blood after urination. Some boys will have ongoing inflammation around the meatus which will respond to topical steroid application (betamethasone 0.05 %).

Meatotomy may be necessary and can be performed under general anesthesia or as an office procedure. Lidocaine/prilocaine (EMLA) cream can be applied topically, covered with a bio-occlusive dressing, and left for one hour before meatotomy with oral midazolam for sedation in selected patients. This can lead to a painless office procedure.104 Once the glans is anesthetized, the ventral web is clamped with a hemostat and left for one minute for hemostasis. The ventral web is then incised one-half the distance to the coronal margin. Parents spread the meatus and apply ointment several times daily for 2–3 weeks. Meatal stenosis rarely recurs. Imaging studies and cystoscopy are not needed.

Megalourethra

Megalourethra is a rare genital anomaly, causing a deformed and elongated penis, that occurs in either a fusiform or scaphoid form (Fig. 56-10). These two forms differ in embryology and appearance. Megalourethra is seen more commonly in patients with prune-belly syndrome and has been reported in association with the VATER (vertebral defects, anorectal atresia, tracheoesophageal fistula, and renal dysplasia) syndrome.105

The less severe and most common form is the scaphoid variety, in which spongiosal tissue fails to invest the urethra.106 The more severe fusiform variety is caused by failure of the penile mesoderm to form spongiosal tissue or corpora cavernosa within the penis.107 It has been found in patients with prune-belly syndrome, stillborn fetuses, and patients with cloacal anomalies.108,109 Associated urologic anomalies have been described, including megacystis, reflux, bladder diverticula, and renal dysplasia.108 Upper tract assessment is indicated in all cases. Repair of the megalourethra relies on hypospadias techniques that tailor the urethra to a more normal size.

Urethral Duplication

Urethral duplications occur in varied forms and can be broadly classified as dorsal or ventral to the normal meatus.110–113 The duplication may be complete, but incomplete forms predominate. Occasionally, side-by-side duplications occur, usually associated with a duplicated phallus and bladder. Most commonly, the two channels form in the sagittal plane. The urethral channel closest to the rectum is generally the more functional conduit, having more normal spongiosal tissue and sphincter mechanism.113 The more dorsal urethra is often small and poorly developed, and will commonly be in an epispadiac position and associated with dorsal chordee. Partial duplications that course along the penile urethra have been called Y-type duplications.114 When the duplicated opening is in the perineum, it has been termed an H-type duplication.115

Treatment of urethral duplications must be individualized. When only a minor septum is present, cystoscopic division of the septum may be successful. Traditionally, with more significant duplications, efforts have been made to lengthen the ventrally-placed urethra to the tip of the penis using various hypospadias reconstruction techniques. Progressive dilation of the dorsal urethral channel to make it functional has also been advocated.116

Congenital Urethral Fistula

A urethral fistula can develop in the anterior urethra with incomplete development of the spongiosum, permitting a small diverticulum to form that ruptures antenatally.117 These are uncommon and difficult to repair due to the lack of spongiosal tissue around the fistula.

Urethral Strictures and Stenosis

Most urethral strictures are acquired. Trauma, inflammatory conditions, and instrumentation by medical personnel are common causes. Congenital urethral stenosis is rare and generally focal. These stenoses are usually in the bulbar urethra, within the area of embryologic joining of the bulbous urethra which arises from genital folds and the posterior membranous urethra which arises from the urogenital sinus. If this junction is misaligned or incompletely canalized, a focal stricture may develop.117

Both of these entities can be treated with an internal urethrotomy, resection and end-to-end anastomosis, or pedicle flap/free graft urethroplasty. One report suggests a single internal urethrotomy for short strictures followed by an open repair for failures may be the best approach.118

Urethral Atresia

In order to be compatible with life, a patent urachus must be present when urethral atresia develops. Reconstruction can be difficult, and a vesicostomy followed by creation of a catheterizable stoma may be the best alternative.98

Urethral Diverticulum or Anterior Urethral Valve

A urethral diverticulum can occur ventrally when the spongiosum is absent or is thinned. The distal lip of the diverticulum functionally serves as an anterior urethral valve, blocking the urinary stream as it flows antegrade (Fig. 56-11). The diverticulum progressively fills during urination and further compresses the urethra. This valve effect can cause marked proximal dilation.119–121 In some cases, there is a diverticulum with a narrow neck that does not function as a valve. Such a diverticulum may allow urinary stasis and can be a site of urethral infection.

FIGURE 56-11 This voiding cystogram shows an anterior urethral diverticulum (asterisk) that functions as a valve, causing outflow obstruction. Note the bladder trabeculation.

The diagnosis is made either by urethrogram or cystoscopy. Treatment is accomplished by endoscopic incision in the distal lip of the neck of the diverticulum or, if more pronounced, by open excision and closure of the urethral defect.122

Cystic Cowper’s Gland Ducts

Cowper’s glands are a pair of small glands located within the urogenital membrane. The ducts from these glands course distally and enter the ventral wall of the proximal bulbar urethra. These are analogous to the female Bartholin’s gland. Occasionally, these ducts become occluded, producing bulbar urethral filling defects and, occasionally, obstruction.123 Cystoscopically, this appears to be a thin membrane over a fluid-filled cyst, sometimes called a syringocele.124 If contrast enters a Cowper’s duct, tubular channels can be seen coursing parallel to the bulbar urethra. Treatment of Cowper’s duct cysts is endoscopic unroofing, but is not necessary unless there are clinical symptoms.

References

1. Yeung, CK, Sihoe, JD. Non-neuropathic dysfunction of the lower urinary tract in children. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, et al, eds. Campbell’s Urology. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2012. [3411–3230].

2. McGuire, E, Woodside, JR, Borden, TA, et al. Prognostic value of urodynamic testing in myelodysplastic patients. J Urol. 1981; 126:205–209.

3. Wan, J, Park, JM. Neurologic control of storage and voiding. In: Docimo SG, Canning DA, Khoury AE, eds. Clinical Pediatric Urology. UK: Informa Healthcare; 2007:765–780.

4. Zderic, S, Chacko, S, DiSanto, ME, et al. Voiding function: Relevant anatomy, physiology, pharmacology, and molecular aspects. In: Gillenwater JY, Grayhack J, Howards SS, et al, eds. Adult and Pediatric Urology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002:1061–1216.

5. Kaefer, M, Zurakowski, D, Bauer, SB, et al. Estimating normal bladder capacity in children. J Urol. 1997; 158:2261–2264.

6. Goellner, M, Ziegler, EE, Fomon, SJ. Urination during the first three years of life. Nephon. 1981; 28:174–178.

7. Allen, T, Kaplan, WE, Kroovand, RL. Sphincter dysynergia. Dialog Pediatr Urol. 1979; 2:1–8.

8. Neveus, T, von Gontard, A, Hoebeke, P, et al. Standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function in children and adolescents: Report from the standardization committee of the International Children’s Continence Society. J Urol. 2006; 176:314–324.

9. Miller, F. Children who wet the bed. In: Kolvin I, McKeith R, Meadow SR, eds. Bladder Control and Enuresis. London: W Heinemann Medical Books Ltd.; 1973:47–52.

10. Tietjen, D, Husmann, DA. Nocturnal enuresis. A guide to evaluation and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996; 71:857–862.

11. Yeung, CK. Nocturnal enuresis (bedwetting). Curr Opin Urol. 2003; 13:337–343.

12. von Gontard, A, Heron, J, Joinson, C. Family history of nocturnal enuresis and urinary incontinence: Results from a large epidemiological study. J Urol. 2011; 185:2303–2306.

13. Forsythe, W, Redmond, A. Enuresis in spontaneous cure rate: Study of 1,129 enuretics. Arch Dis Child. 1974; 49:259–263.

14. Bakwin, H. The genetics of enuresis. In: Kolvin I, MacKeith R, Meadow S, eds. Bladder Control and Enuresis. London: WP Heinemann Medical Books Ltd.; 1973:73–77.

15. Norgaard, J. Urodynamics in enuresis 1: Reservoir function pressure-flow study. Neurourol Urodyn. 1989; 8:199–211.

16. Norgaard, J. Pathophysiology of nocturnal enuresis. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl. 1991; 140:1–35.

17. Jarvelin, M. Developmental history and neurological findings in enuretic children. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1989; 31:728–736.

18. Norgaard, J, Hansen, J, Nielsen, J, et al. Simultaneous registration of sleep stages and bladder activity in enuresis. Urology. 1985; 26:316–319.

19. Norgaard, J, Pedersen, E, Djurhuus, J. Diurinal antidiuretic – Hormone levels in enuretics. J Urol. 1985; 134:1029–1031.

20. Puri, VN. Urinary levels of antidiuretic hormone in nocturnal enuresis. Indian Pediatrics. 1980; 17:675–676.

21. Rushton, H, Belman, AB, Zaontz, MR, et al. The influence of small functional bladder capacity and other predictors on the response to desmopressin the management of monosymptomactic nocturnal enuresis. J Urol. 1996; 156:651–655.

22. Eller, D, Austin, PF, Tanguay, S, et al. Daytime functional bladder capacity as a predictor of response to desmopressin in monosymptomatic nocturnal enureseis. Eur Urol. 1998; 33:25–29.

23. Hansen, M, Rettig, S, Siggaared, C, et al. Intra-individual variability in nighttime urine production and functional bladder capacity estimated by home recordings in patient with nocturnal enuresis. J Urol. 2001; 166:2452–2455.

24. Monda, J, Husmann, D. Primary nocturnal enuresis: A comparison among observation, Imipramine, Desmopressin Acetate and bedwetting alarm systems. J Urol. 1995; 154:745–748.

25. Glazener, CM, Evans, JHC, Peto, RE. Alarm interventions for nocturnal enuresis in children. Cochrane Data Syst Rev. (2):2005.

26. Glazener, CM, Evans, JHC, Peto, R. Tricyclic and related drugs for nocturnal enuresis in children. Cochrane Data Syst Rev. (Issue 3):2003.

27. Blackwell, B, Currah, J. The psychoparmacology of nocturnal enuresis. In: Kolvin I, MacKeith R, Meadow S, eds. Bladder Control and Enuresis. London: W Heinemann Medical Books Ltd; 1973:231–257.

28. Klauber, G. Clinical efficacy and safety of desmopressin in the treatment of nocturnal enuresis. J Pediatr. 1989; 114:719–722.

29. Rittig, SM, Knudsen, U, Sorensen, S, et al, Desmopressin and nocturnal enuresis: Proceedings of an internal symposium. Meadow S. Horus Medical Publications, England, London, 1989:43–54.

30. Zong, H, Yang, C, Peng, X, et al. Efficacy and safety of desmopressin for treatment of nocturia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of double-blinded trials. Int Urol Nephrol. 2011; 44:377–384.

31. Robson, W. Diurnal enuresis. Pediatr Review. 1997; 18:407–412.

32. MacKeith, R, Meadow, S, Turner, R. How children become dry. In: Kolvin I, MacKeith R, Meadow S, eds. Bladder Control and Enuresis. Philadelphia: LB Lippincott Co.; 1973:3–21.

33. Bernard-Bonnin, A. Diurnal enuresis in childhood. Canad Fam Physician. 2000; 46:1109–1115.

34. Fernandes, E, Veraier, R, Gonzalez, R. The unstable bladder in children. J Pediatr. 1991; 118:831–837.

35. Reinberg, Y, Crocker, J, Wolpert, J, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of extended release oxybutynin chloride and immediate release and long-acting tolterodine tartrate in children with diurnal urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2003; 169:317–319.

36. Munding, M, Wessells, H, Thornberry, B, et al. Use of tolterodine in children with dysfunctional voiding: an initial report. J Urol. 2001; 165:926–928.

37. Goessl, C, Sauter, T, Michael, T, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of tolterodine in children with detrusor hyperreflexia. Urology. 2000; 55:414–418.

38. Herndon, CD, Decambre, M, McKenna, PH. Interactive computer games for treatment of pelvic floor dysfunction. J Urol. 2001; 166:1893–1898.

39. McKenna, PH, Herndon, CD, Connery, S, et al. Pelvic floor muscle retraining for pediatric voiding dysfunction using interactive computer games. J Urol. 1999; 162:1056–1062.

40. Koenig, JF, McKenna, PH. Biofeedback therapy for dysfunctional voiding in children. Curr Urol Rep. 2011; 12:144–152.

41. Lordelo, P, Teles, A, Veiga, ML, et al. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in children with overactive bladder: A randomized clinical trial. J Urol. 2010; 184:683–689.

42. DeGennaro, M, Capitanucci, ML, Mosiello, G, et al. Current state of nerve stimulation technique for lower tract dysfunction in children. J Urol. 2011; 185:157–1577.

43. Koff, S, Murtagh, DS. The uninhibited bladder in children: Effect of treatment on recurrence of urinary infection and vesico-ureteral reflux. J Urol. 1983; 130:1158–1160.

44. DeLuca, F, Swenson, O, Fisher, JH, et al. The dysfunctional “lazy”bladder syndrome in children. Arch Dis Child. 1962; 37:197–223.

45. Bloom, D, Seeley, WW, Ritchey, ML, et al. Toliet habits and continence in children: An opportunity sampling in search of normal parameters. J Urol. 1993; 149:1087–1090.

46. Hinman, F. Non-neurogenic neurogenic bladder (the Hinman syndrome) fifteen years later. J Urol. 1986; 136:769–775.

47. Austin, P, Homsy, YL, Masel, JL, et al. Alpha-adrenegic blockage in children with neuropathic and non-neuropathic voiding dysfunction. J Urol. 1999; 162:1064–1067.

48. Austin, P. The role of alpha blockers in children with dysfunctional voiding. Scientific World Journal. 2009; 9:880–883.

49. Bauer, S. Neurogenic voiding dysfunction and non-surgical management. In: Docimo SG, Canning DA, Houry AE, eds. Clinical Pediatric Urology. UK: Informa Healthcare; 2007:781–818.

50. Steers, W, Barrett, DM, Wein, AJ. Voiding dysfunction: diagnosis, classification and management. In: Gillenwater JY, Grayhack JT, Howards SS, et al, eds. Adult and Pediatric Urology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002:1115–1216.

51. Mandell, J, Bauer, SB, Hallett, M, et al. Occult spinal Dysraphism: A rare but detectable cause of voiding dysfunction. Urol Clin North Am. 1980; 7:349–356.

52. Kaplan, W. Management of myelomeningocele. Urol Clin North Am. 1985; 12:93–101.

53. MacLellan, DL, Bauer, SB. Infection of the lower urinary tract. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, et al, eds. Campbell’s Urology. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:2193–2216.

54. Bauer, S, Joseph, DB. Management of the obstructed urinary tract associated with neurogenic bladder dysfunction. Urol Clin North Am. 1990; 17:395–406.

55. Weler, M, Shapiro, S, Mitchell, AA. Periconceptual folic acid exposure and risk of occult neural tube defects. JAMA. 1993; 269:1257–1263.

56. Bauer, S, Hallett, M, Khoshbin, S, et al. Predictive value of urodynamic evaluation in newborns with myelodysplasia. JAMA. 1984; 252:650–652.

57. Wang, S, McGuire, EJ, Bloom, DA. A bladder pressure management system for myelodysplasia: Clinical outcome. J Urol. 1988; 140:1499–1502.

58. Galloway, N, Mekras, JA, Helms, M, et al. An objective score to predict upper tract deterioration in myelodysplasia. J Urol. 1991; 145:535–537.

59. Adzick, NS, Thom, EA, Spong, CY, et al. A randomized trial of prenatal versus postnatal repair of myelomeningocele. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364:993–1004.

60. Carr, MC. Fetal myelomeningocele repair: Urologic aspects. Curr Opin Urol. 2007; 17:257–261.

61. Tarcan, R, Bauer, S, Olmedo, E, et al. Long-term follow up of newborns with myelodysplasia and normal urodynamic findings: Is it necessary? J Urol. 2001; 165:564–567.

62. Lapides, J, Diokno, AC, Silber, SJ, et al. Clean intermittent self-catheterization in the treatment of urinary tract disease. J Urol. 1971; 107:458–462.

63. Klose, A, Sackett, CK, Mesrobian, H. Management of children with myelodysplasia: Urologic alternatives. J Urol. 1990; 144:1446–1449.

64. Joseph, D, Bauser, SB, Colodny, AH, et al. Clean intermittent catheterization of infants with neurogenic bladder. Pediatrics. 1989; 84:78–82.

65. Cass, A. Urinary tract complications in myelomeningocele patients. J Urol. 1976; 115:102–104.

66. Plunkett, J, Braren, V. Clean intermittent catheterization in children. J Urol. 1979; 121:469–471.

67. Klauber, G, Sant, GR. Complications of intermittent catheterization. Urol Clin North Am. 1983; 10:557–562.

68. Abrams, P. Tolterodine, a new antimuscarinic agent: As effective but better tolerated than oxybutynin in patients with an overactive bladder. Br J Urol. 1998; 81:801–810.

69. Dmochowski, R, Davila, G, Zinner, N, et al. Efficacy and safety of transdermal oxybutynin in patients with urge and mixed urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2002; 168:580–586.

70. Schulte-Baukloh, H, Knispel, HH, Stolze, T, et al. Repeated botulinum-A toxin injections in treatment of children with neurogenic detrusor overactivity. Urology. 2006; 66:865–870.

71. Patel, AK, Patterson, JM, Chapple, CR. Botulinum toxin injections for neurogenic and idiopathic detrusor overactivity: A critical analysis of results. Eur Urol. 2006; 50:684–709.

72. Duckett, JJ. Cutaneous vesicostomy in childhood. Urol Clin North Am. 1974; 1:485–495.

73. Mandell, J, Bauer, SB, Colodny, AH, et al. Cutaneous vesicostomy in infancy. J Urol. 1981; 126:92–93.

74. Bloom, D, Knechtel, JM, McGuire, EJ. Urethral dilation improve bladder complicance in children with myelomeningocele and high leak point pressures. J Urol. 1990; 144:430–433.

75. Jeffs, R, Jonas, P, Schillinger, JF. Surgical correction of vesicoureteral reflux in children with neurogenic bladder. J Urol. 1976; 114:449–451.

76. Agarwal, S, McLorie, GA, Grewal, D, et al. Urodynamic correlates of resolution of reflux in myelomeningocele patients. J Urol. 1997; 158:580–582.

77. Adams, M, Mitchell, ME, Rink, RC. Gastrocystoplasty: An alternative solution to the problem of urological reconstruction in the severely compromised patient. J Urol. 1988; 140:1152–1156.

78. Adams, M, Bihrle, R, Rink, RC. The use of stomach in urologic reconstruction. AUA Update Series. 1995; 14:218–223.

79. Nguyen, D, Bain, MA, Salmonson, KL, et al. The syndrome of dysuria and hematuria in pediatric urinary reconstruction with stomach. J Urol. 1993; 150:707–709.

80. Cartwright, P, Snow, BW. Bladder augmentation: Early clinical experience. J Urol. 1989; 142:595–598.

81. Snow, B, Cartwright, PC. Bladder augmentation. Urol Clin North Am. 1996; 23:323–331.

82. Gonzalez, R, Buson, H, Reid, C, et al. Seromuscular colocystoplasty lined with ureothelium: Experience with 16 patients. Urology. 1994; 45:124–129.

83. Dewan, P, Byard, R. Autoaugmentation gastrocystoplasty in a sheep model. Br J Urol. 1993; 72:56–59.

84. Atala, A, Bauer, SB, Soker, S, et al. Tissue-engineered autologous bladders for patients needing cystoplasty. Lancet. 2006; 367:1241–1246.

85. Reda, E. The use of the Young-Dee Leadbetter procedure. Dialog Pediatr Urol. 1991; 14:7–8.

86. Kropp, K, Angwafo, FF. Urethral lengthening and reimplantation for neurogenic incontinence in children. J Urol. 1986; 135:533–536.

87. Kropp, K. Management of urethral incompetence in the patient with neurogenic bladder. Dialo Pediatr Urol. 1991; 14:6–7.

88. Salle, J, McLorie, GA, Bagli, DJ, et al. Urethral lengthening with anterior bladder wall flap (Pippi Salle procedure): Modification and extended indications of the technique. J Urol. 1997; 158:585–590.

89. McGuire, J, Lytton, B. Pubovaginal sling procedure for stress incontinence. J Urol. 1978; 119:82–84.

90. Bauer, S, Peters, CA, Colodny, AH, et al. The use of rectus fascia to manage urinary incontinence. J Urol. 1989; 142:516–519.

91. McGuire, E, Wang, C, Usitalo, H, et al. Modified pubovaginal sling in girls with myelodysplasia. J Urol. 1986; 135:94–96.

92. Elder, J. Periurethral and puboprostatic sling repair for incontinence in patients with myelodysplasia. J Urol. 1990; 144:434–437.

93. Norbeck, J, McGuire, EJ. The use of pubovaginal and puboprostatic slings. Dialogs Pediatr Urol. 1991; 14:3–4.

94. Gonzalez, R, Nguyen, DH, Koleilat, N, et al. Compatibility of enterocystoplasty and the artificial urinary sphincter. J Urol. 1989; 152:502–504.

95. Dyer, L, Franco, I, Firlit, CT, et al. Endoscopic injection of bulking agents in children with incontinence: Dextranomer/hyaluronic acid copolymer versus polytetrafluroethylene. J Urol. 2007; 178:1628–1631.

96. Lottmann, HB, Margaryan, M, Lortat-Jacob, S, et al. Long-term effects of dextranomer endoscopic injections for the treatment of urinary incontinence: An update of a prospective study of 61 patients. J Urol. 2006; 176:1762–1766.

97. Mitrofanoff, P. Cystostomie continente trans-appendiculaire dans le traitement des vessies neurolgigues. Chir Pediatr. 1980; 21:297–301.

98. Cain, M, Casale, A, King, S, et al. Appendicovesicostomy and newer alternatives for Mitrofanoff procedure: Results in the last 100 patients at Riley’s Children’s Hospital. J Urol. 1999; 162:1749–1752.

99. Keating, M, Rink, RC, Adams, MC. Appendicovesicostomy: A useful adjunct to continent reconstruction of the bladder. J Urol. 1993; 149:1091–1094.

100. Monti, P, Lava, R, Dutra, M, et al. Newer techniques for construction of efferent conduits based on mitrofanoff principle. Urology. 1997; 49:112–115.

101. Cass, A, Luxenberg, M, Gleich, P, et al. A 22 year follow up of ileal conduits in children with a neurogenic bladder. J Urol. 1984; 132:529–531.

102. Husmann, D, McLorie, GA, Churchill, BM. Nonrefluxing colonic conduits: A long-term life table analysis. J Urol. 1989; 142:1201–1205.

103. Brown, M, Cartwright, P, Snow, B. Common office problems in pediatric urology and gynecology. In: Pediatri Clin North Am. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1997:10911–11115.

104. Cartwright, P, Snow, B, McNees, D. Office meatotomy utilizing EMLA cream as the anesthetic. J Urol. 1996; 156:857–859.

105. Fernbach, S. Urethral abnormalities in male neonates with VATER association. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991; 156:137–140.

106. Stephens, F, Smith, ED, Huston, JM. Congenital intrinsic lesions of the anterior urethra. In: Congenital Anomalies of the Urinary and Genital Tracts. Oxford, England: Isis Media; 1996:119–124.

107. Dorairajan, T. Defects of spongy tissue and congenital diverticuli of the penile urethra. Aus NZJ Surg. 1963; 32:209–214.

108. Hudson, RG, Skoog, SJ. Prune-Belly Syndrome. In: Docimo SG, Canning DA, Khoury AE, eds. Clinical Pediatric Urology. UK: Informa Healthcare; 2007:1081–1114.

109. Shrom, S, Cromie, W, Duckett, J, et al. Megalourethra. Urology. 1981; 17:152–156.

110. Gross, R, Moore, T. Duplication of the urethra. Arch Surg. 1950; 60:749.

111. Das, S, Brosman, S. Duplication of the male urethra. J Urol. 1977; 117:452–454.

112. Woodhouse, C, Williams, D. Duplications of the lower urinary tract in children. Br J Urol. 1979; 51:461–487.

113. Salle, J, Sibai, H, Rosenstein, D, et al. Urethral duplication in the male: Review of 16 cases. J Urol. 2000; 163:1936–1938.

114. Williams, D, Bloomberg, S. Bifid urethra with three anal accessory tract (Y Duplication). Br J Urol. 1976; 47:877–882.

115. Stephens, F, Donnellan, W. H-Type urethral anal fistula. J Pediatr Surg. 1977; 12:95–102.

116. Passerini-Glazal, G, Araguna, F, Chiozza, L. P.A.D.U.A. (Posterior augmentation by dilating the urethra anterior). Procedure of choice for treatment of severe urethral hypoplasia. J Urol. 1988; 140:1247–1249.

117. Duckett, J, Snow, B. Disorders of the urethra and penis. In: Walsh P, Gittes R, Perlmutter A, Stamey T, eds. Campbell’s Urology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co.; 1986:2014–2015.

118. Hsaio, K, Baez-Trinidad, L, Lendvay, T, et al. Direct vision internal urethrotomy for the treatment of pediatric urethral strictures: Analysis of 50 patients. J Urol. 2003; 170:052.955.

119. Firlit, C, King, L. Anterior urethral valves in children. J Urol. 1972; 108:972–975.

120. Rudhe, U, Ericsson, N. Congenital urethral diverticuli. Ann Radiol. 1970; 13:289.

121. Williams, D, Retik, A. Congenital valves and diverticuli of the anterior urethra. Br J Urol. 1969; 41:228–234.

122. Firlit, R, Firlit, C, King, L. Obstruction anterior urethral valves in children. J Urol. 1978; 119:819–821.

123. Colodny, A, Lebowitz, R. Lesions of Cowper’s ducts and gland in infants and children. Urology. 1978; 11:321–325.

124. Maizel, S, Stephens, F, King, L, et al. Cowper’s syringocele: A classification of dilatations of Cowper’s gland duct based upon clinical characteristics of eight boys. J Urol. 1983; 129:111–114.