Blackouts and ‘funny do’s’

Blackouts are one of the most common presentations in neurology, accounting for 18% of new neurological outpatients. The most common causes are seizures or syncope. While a list of possible causes is long, the clinical history, particularly with an account from a witness, will usually define the nature of the attack and direct investigations.

Types of blackouts and ‘funny do’s’

Episodes with collapse

Tonic-clonic seizure

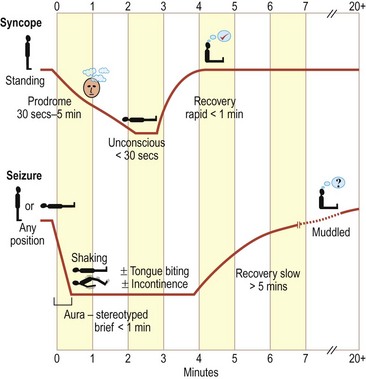

These may occur at any time and in any position (Fig. 1). The patient may have a warning (aura), such as a smell or taste or simply a strange feeling (see below). The aura is usually brief (a few seconds). There may be no warning. The patient may be observed to go blank or be lip smacking before losing consciousness. The patient then goes stiff and lets out a grunt. The arms and legs go stiff for a period and the jaw is clenched tight. This may be followed by a jerking of the limbs. This usually goes on for 2–3 min. The patient usually goes into a deep sleep. On coming round, the patient is muddled. Patients frequently bite their tongue and pass urine.

Syncope

There may be factors in the situation of the blackout that suggest syncopal episodes:

If it occurred after prolonged standing, in a hot place or after some distress such as the sight of blood. All these suggest a vasovagal syncope.

If it occurred after prolonged standing, in a hot place or after some distress such as the sight of blood. All these suggest a vasovagal syncope. If it is preceded by a palpitation, occurs without any prodrome or occurs with exertion – all suggest cardiac syncope, e.g. due to an arrhythmia or obstructive cardiomyopathy.

If it is preceded by a palpitation, occurs without any prodrome or occurs with exertion – all suggest cardiac syncope, e.g. due to an arrhythmia or obstructive cardiomyopathy. If it occurred in particular situations, e.g. micturition (micturition syncope) or cough (cough syncope).

If it occurred in particular situations, e.g. micturition (micturition syncope) or cough (cough syncope).Rarer causes of collapse

Subarachnoid haemorrhage

This may present with sudden severe headache followed by loss of consciousness.

Sleep disorders

These can enter the differential diagnosis of blackouts: a tendency to fall asleep suddenly and unexpectedly is seen in narcolepsy and sometimes in obstructive sleep apnoea. Patients with narcolepsy also may have episodes of loss of muscle tone at times of high emotion, such as laughter or tears: cataplexy.

Episodes without collapse

Partial seizures and complex partial seizures

Transient ischaemic attacks

The sudden onset of loss of any function of the nervous system can arise from vascular causes. Only rarely is consciousness lost (p. 70).

Migraine

Migraine may cause focal neurological symptoms of gradual onset over about 15–30 min. Typically these are visual symptoms, though numbness, tingling or speech disturbance can occur. The typical headache usually follows (p. 42), but may not, which may lead to consideration of other differential diagnoses (Table 1).

Table 1 Pattern of sensory and other symptoms in different types of attack

| Diagnosis | Typical duration | Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Partial seizure | Seconds to 3 minutes | Positive |

| Migraine | 10–30 minutes | Positive and negative |

| Transient ischaemic attack | Minutes to hours | Negative |

Investigation

This is directed by the history. All patients who faint should have an ECG. Although the yield is low, rare arrhythmias such as long Q-T syndrome should be excluded. If the patient is thought to have had a syncopal attack, the following investigations may be considered: fasting glucose, 24-h ECG, echocardiogram or tilt table test. If the patient is thought to have had a seizure, the following investigations could be considered (see p. 74 for discussion): MRI or CT brain scan, EEG, 24-h EEG or calcium. If the diagnosis is uncertain, investigation should be directed towards both syncope and seizure, concentrating particularly on treatable options.

Management

Management will depend on the cause. Patients who have had a blackout need to be advised about the regulations relating to driving (Box 1) and common sense advice about lifestyle, to avoid any situation that could put them or anyone else at risk, for example swimming; showering instead of taking a bath.

| Situation | Rule |

|---|---|

| Single seizure or blackout with seizure markers | Licence revoked for 1 year; 6 months if ECG and scan are normal |

| Single provoked seizure | Dealt with by DVLA on an individual basis Must inform DVLA |

| Recurrent seizures | Licence revoked until seizure free for 1 year |

| Seizures in sleep only | May drive despite continuing seizures, providing all seizures have been in sleep for at least 3 years |

| Transient ischaemic attacks | Usually can drive 1 month after a single episode |

| Transient global amnesia | No effect on driving |

| Simple faint | No effect on driving |