Chapter 56 Bites and Injuries Inflicted by Wild and Domestic Animals

For online-only figures, please go to www.expertconsult.com ![]()

Wild and domestic animal bites are distinct from other injuries suffered by humans. Tearing, cutting, and crushing injuries may be combined with blunt trauma caused by falls. Animal bites may cause local infection, and offending bacteria reside in numerous environmental sources. However, few traumatic lacerations are as regularly contaminated with as broad a variety of pathogens as are animal bites. Domestic animal bites are common, and their incidence is rising.43,201,297 Wild animal attacks are often more spectacular; however, in the developed world, injuries from domestic animals have a much greater health and economic impact. Humans are not a preferred natural prey of any animal, and, although some attacks are predatory, most attacks are caused by fear of humans (real or perceived), territoriality, protective instinct, or accident. Unfortunately, wild animal attacks may be sensationalized by the lay press, and animals given anthropomorphic characteristics that do not accurately reflect their instinctive responses; this may lead to public misunderstanding of animal behavior. Press reports may ignore the fact that wild animal attacks are rare and that wild animals are far less likely to cause injury than are their domestic counterparts.

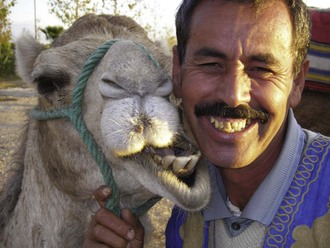

As human settlements and populations continue to grow and encroach on the natural world, the incidence of human–animal encounters will increase. Adventure-seeking humans may also seek out animal encounters that historically would have been avoided. A wolf sighting 100 years ago would have been cause for alarm, yet today people travel to Yellowstone National Park to see wolves in the wild and hope to get close enough to take pictures. The increased pressure of human proximity to animals increases the likelihood of an encounter resulting in a negative outcome (Figure 56-1).40

Other special features of human–animal encounters include attacking animals that may terrorize the victim and transmission of systemic diseases, many of which might cause substantial morbidity and mortality (for a discussion of zoonoses, see Chapter 59). In addition, treatment decisions are often made without a strong scientific basis, and management of wild animal attack victims is often based on a much more robust experience with domestic animal attacks (i.e., dog and cat bites).

General Epidemiology

According to the 2008 National Pet Owner Survey, 39% of all households in the United States own a total of 74.8 million dogs, and 34% own 88.3 million cats.10 During 1 year in Pennsylvania, county health officials reported 16,000 animal bites, 75% of which were dog related; the highest incidence of dog bite was among children less than 5 years old. Three-quarters of persons injured received wound treatment, and one-half received antimicrobials. Postexposure rabies prophylaxis administration was prescribed for attacks by species as follows: 44% for cats, 30% for dogs, 7% for raccoons, 4% for bats, 2.5% for squirrels, 2.1% for groundhogs, 2% for foxes, and 8% for all other species.230

Each year, dogs bite 1.8% of all Americans, resulting in 4.7 million wounds. More than 750,000 of these victims seek medical attention.75 Bites to children are common, especially among boys between the ages of 5 to 9 years.75 Over the course of 1 year in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 790 dog bites were reported, but an estimated 1388 went unreported; the annual incidence was 58.9 bites per 10,000 individuals.81 Of 279 reported injuries caused by animals to travelers, 51% were caused by dogs, 21% by monkeys, 8% by cats, and 1% by bats.144 In India, where stray dogs cause 96% of rabies cases, the annual dog bite rate is 25.7 per 1000 individuals, and the most common victims are males.3,86

The annual incidence of cat bites in the United States is approximately 400,000.303 A cat bites one in every 170 people each year, and 80% of these bites become infected.156 Biting cats are typically stray females, and most human victims are female.

Of the approximately 30 million Americans who ride horses, 50,000 a year are treated for horse-related injuries in an emergency department, principally because the rider is unrestrained and can fall off while traveling at speeds of up to 64.4 km/hr (40 mph). Horses can kick with a force of up to 907 kg (1 ton), and frequently bite. A 2-year review of animal bites in Oslo, Norway, revealed that horses caused 2% of 1051 recorded bites; 53% of these horse bite victims were children.104

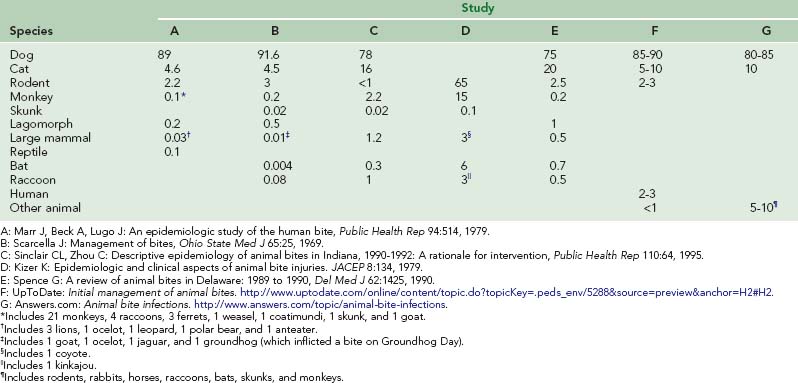

The American Ferret Association estimates that 6 to 8 million domesticated ferrets reside in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that the number of bites inflicted by ferrets—65 reported bites in 10 years—is substantially lower than that caused by dogs and cats (i.e., between 1 and 3 million)23 (Table 56-1). In Arizona, 11 ferret bites were reported over 11 months; with the ferret population estimated at 4000, the reported bite-to-ferret population ratio is approximately 0.3%.316 The risk of attack by a ferret is greatest among infants and small children.

In Sweden, 3 in 1000 citizens are injured by animals each year.46 Domestic animals accounted for more than 90% of injuries, moose accounted for 6% (almost all were involved in auto accidents), and all other animals accounted for 4%. However, bites were not examined separately, and many injuries occurred during vehicular accidents with animals. Some officials estimate there are two additional bites for every one reported, but a survey of children between the ages of 4 and 18 years old estimated an incidence of more than 36 times the reported bite rate. These figures are most likely based on domestic bites, although this was not specifically stated.32,33 During a 7-year period in Texas, 2% of all large-animal–related trauma was caused by wild animal attacks.243 From 2001 to 2005, there were 472,760 reports by poison control centers of animal bites and stings, which is an average of 94,552 reports per year.202

A 2006 GeoSentinel review of injuries to travelers from 1998 to 2005 showed a total of 320 reported animal-related injuries (i.e., 1.8% of all reported injuries).144 The review revealed that, among travelers, women were more likely than men to be injured by animals. Men were more likely to be injured by dogs, women by monkeys, and children suffered animal injuries at a higher rate than any other travel-related injury. By geographic region, travelers were most likely to experience animal-related injuries in Southeast Asia, followed by Asia, Australia and New Zealand, Africa, Latin America, North America, and Europe.144

Typical Victim

No published reports characterize the typical wild animal attack victim. Two U.S. state health departments report that, if all animal bites (including domestic) are considered, animal bites occur most often among male children between the ages of 5 and 9 years.302,306 However, more than 90% of animal attacks in these states are caused by domestic animals, so this group may not accurately reflect the typical victim of a wild animal attack. In developing countries, many persons are exposed daily to biting animal species that are considered “exotic” in the developed world.

Persons in certain occupations in developed countries (e.g., veterinary and animal control workers, laboratory workers) are at greatest risk for wild animal bites. One study reported that 65% of veterinarians had suffered an animal-related injury during the preceding 12 months.200 The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that, during a 5-year period, 186 occupational injury fatalities were caused by animal attacks and that the majority involved cattle.58 In one study of 102 animal control officers, the overall bite rate was 2 per 57 individuals per working day, which is 175 to 500 times the estimated rate for the general population (this study did not differentiate between wild and domestic animal bites).32 The incidence of biting varies with species exposure. In 2003, 93% of Wisconsin and Minnesota veterinarians were victims of dog or cat bites. Cattle and horses inflict the most injuries to veterinarians, with kicking, biting, and crushing being the top three mechanisms of injury.116

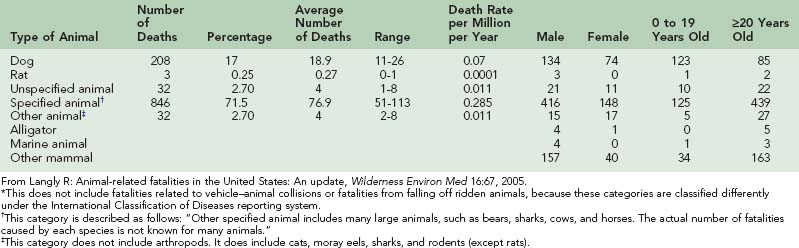

Several thousand people per year are killed by mammalian bites, with most of the deaths inflicted by maneating lions and tigers in Africa and Asia (Table 56-2). By way of comparison, the World Health Organization estimates that 5 million people per year are bitten and 125,000 killed by snakes and that additional millions are killed by insect-borne diseases.349

An estimated 200 persons are killed by animals in the United States each year; 131 of these die in traffic accidents involving deer.170 Bees kill approximately 43 persons, dogs 14, and rattlesnakes 10. Wild animals (e.g., bears, cougars) kill fewer people than do goats, rats, jellyfish, and captive elephants. More than 3 million people visit the wilderness in Yellowstone National Park every year, but the incidence of serious injuries by bears in the park is less than that of being struck by lightning.162

Circumstances Surrounding and Prevention of Animal Bites: Animal Behavior

Analysis of unintentional injuries shows that these are not random events but rather, are predictable events and have identifiable personal and environmental risk factors similar to those of diseases.350 For example, family pets cause most bites, and the animals are usually provoked in some way. Boys experience 150% to 250% the rate of injuries as compared with girls at every age350 (Table 56-3). Injuries are frequently sustained while playing with the animal.81 Most bites occur in the summer months during the late afternoon. Children sustain a higher percentage of head and neck bites than do adults and are more likely to require medical attention.130 Of all dog bites, 9% to 36% occur to the head and neck region, whereas this area is affected in 6% to 20% of persons who sustain cat bites.130 Understanding such patterns of animal bite injuries allows for improved prevention and treatment.

TABLE 56-3 Selected Demographics for Animal-Related Fatalities in the United States From 1991 to 2001* (Based on the International Classification of Diseases Reporting System Codes)

Prevention of animal bites requires thorough knowledge of the patterns of behavior and personalities of various species of animals. A person who wishes to avoid the bite of a particular species will often be able to gain expertise about that species’ behavior only from those who work with it regularly. Detailed information about animal behavior and the attack patterns of animals is also available on the Internet (Box 56-1).

BOX 56-1 Animal Behavior and Attack Prevention Websites

| Dog and cat bite prevention | http://www.cityoffortwayne.org/animal-bite-prevention.html |

| Dog bite prevention | http://www.petplace.com/dogs/preventing-dog-bites-things-to-do-before-you-get-a-dog/page1.aspx |

| Dog bite prevention and legal information | http://www.dogbitelaw.com |

| Moose attack prevention | http://www.survivaltopics.com/survival/survive-a-moose-attack/ |

| Cougar attack prevention | http://www.arkanimals.com/dlg/cougar_attack.htm |

| Wolf behavior and human encounters | http://fwp.mt.gov/wildthings/wolf/human.html |

| Hunter education | http://www.hunter-ed.com/index.html |

| General animal attack information | http://www.articlesbase.com/health-and-safety-articles/how-to-avoid-animal-attack-injury-444613.html |

| Wild animal attack compilation | http://www.attack.igorilla.com |

Basic Principles for Avoiding Animal Bites

Expert recommendations can reduce the chance of being attacked and bitten by a domestic animal (Box 56-2). Specific actions can be taken when an individual is threatened or under attack by a dog (Box 56-3). Dogs are guided by memory and instinct; fear and self-preservation are very strong instincts, so any perceived threat could lead to an attack. Territoriality is still ingrained in domestic dogs, even if humans provide for them. Protection of food can cause aggression, even in a docile dog. Any threat to a dog’s mate, offspring, or owner may result in an attack. Personality changes may lead to aggression; causes include illness (e.g., distemper) and physiologic factors (e.g., a female in heat).

BOX 56-2 Advice for Avoiding the Bites and Attacks of Common Pets*

Dogs

BOX 56-3

Suggested Actions If You Are Under Threat or Attacked By a Dog

Modified from Wilson S: Bite busters: How to deal with dog attacks, New York, 1997, Simon & Schuster; and wikiHow: How to handle a dog attack. http://www.wikihow.com/Handle-a-Dog-Attack.

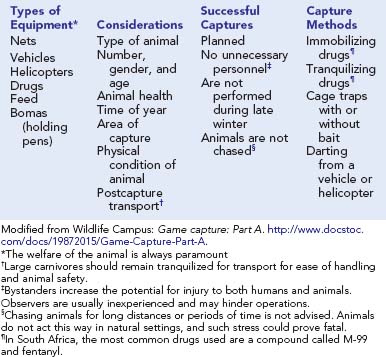

People often capture or restrain wild animals, thereby creating stress that may cause even the most benign animal to attack its captor. Allegedly tame animals are very likely to struggle. Even shy animals that are being captured for treatment of an injury may attack in self-defense and can inflict a life-threatening injury (e.g., goring). Therefore, all situations that involve animal restraint and capture are considered high risk, and careful study of the species’ behavior, the individual animal, and the physical environment and available resources should precede actual attempts at restraint (see Chapter 61).

Because people seem drawn to raising wild animals as pets,211 a large and lucrative market exists, particularly in the United States. No matter how they are raised, these animals remain wild and will never be as predictable, trustworthy, and nonaggressive as animals that have been domesticated for centuries. Often owners of these animals demonstrate a lack of common sense; consider the case of a pet Bengal tiger that attacked and killed its trainer, then did the same to its owner 6 weeks later.21,112

A major principle of animal behavior is that physical attack is often the animal’s last resort. Animals generally give ample warning regarding their intentions. Elaborate rituals and rules that encourage a nonviolent solution so that the victor may successfully defend its territory and itself with little or no injury govern spectacular contests between animals that occur in the wild. Humans can often avoid attack and injury by successfully interpreting visual, auditory, and olfactory warning signs. If a human slowly and carefully backs away without making sudden or threatening gestures, usually no harm will be done. However, the ideal reaction depends on the species. For example, mountain lions have been turned from a full charge by a human who acted aggressively or fought back.35 Given a choice of victims, such a predator prefers the fleeing and panicked victim who demonstrates expected behavior patterns.

If capture of an animal is essential, detailed preparation should be undertaken. For small animals, using nets or heavy cloth and wearing extremely heavy gloves and other protective clothing are advisable. Desperate animals can bite with tremendous force; large carnivores can easily amputate a gloved digit. A wolf can tear apart a stainless steel bowl with its teeth, and a hyena can bite through a 2-inch–thick wooden plank.92 Four men are needed to subdue an adult chimpanzee; an orangutan can maintain a one-fingered grip that an adult human cannot break. Larger animals generally require a team approach by animal control specialists with equipment such as nets, barriers, cages, and immobilizing drugs. Ideal immobilization techniques for various species are detailed in veterinary and wildlife management publications137,142 (Box 56-4).

Evaluation and Treatment of Injuries: Prehospital Care

Many of the complications and serious infections that occur as a result of animal bites are caused by inadequate first aid and delays in medical care. Local wound treatment should be initiated at the scene of the bite (Box 56-5); more than any other therapy, this can determine the course of healing. Simple first-aid measures must be initiated immediately unless definitive or better treatment is available within a short time. Pressure on the wound or pressure points controls most bleeding; avoid tourniquets unless blood loss cannot otherwise be controlled. If the victim is more than 1 hour from a treatment facility, cleanse the wounds at the scene as soon as resuscitation efforts are complete. Early cleansing reduces the chance of bacterial infection and is extremely effective for killing rabies and other viruses. Potable water, preferably boiled or treated with germicidal agents, is adequate for wound irrigation. Ordinary hand soap adds some bactericidal, virucidal, and cleansing properties. If 1% to 5% povidone–iodine in normal saline solution is available, it should be used as an irrigant. Alternatively, thoroughly irrigate the wound with at least a pint of soapy water and then gently debride it of dirt and foreign objects by swabbing with a soft, clean cloth or sterile gauze. Irrigation with a syringe is preferable (see Chapter 22).

BOX 56-5 Summary of Mandatory Animal Bite Wound Treatment for All Wounds

Selective Treatment (Wounds Selected By Risk Factors)

After cleansing, cover the wound with sterile dressings or a clean, dry cloth. Wounds of the hands or feet require immobilization. If the wounds are at high risk for infection, treatment is hours away, and an antibiotic such as amoxicillin–clavulanate (first line), a fluoroquinolone plus clindamycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole plus clindamycin, amoxicillin plus cephalexin (less effective), azithromycin, or doxycycline is available,1,102,308 then it is reasonable to start immediate treatment with an oral dose (Box 56-6). To most effectively prevent subsequent wound infection, antibiotics should be started within 1 hour of wounding. However, with a severe wound, it is worthwhile to provide the antibiotic, even if delivered substantially later. If antibiotics are unavailable, the wound is infection prone, and medical care is delayed, a simple remedy such as filling the wound with honey may be an effective antibacterial strategy.264 Because of its high osmolarity and weak hydrogen peroxide concentration when diluted, honey can be effective as an antibacterial when used in adequate quantities, although there are no randomized controlled trials to support this recommendation. The wound should be flooded with honey that has been slightly thinned with water and kept flooded like this until definitive treatment is available. The amount of honey needed will depend on the amount of exudate from the wound (because of dilution), and the frequency of dressing changes will depend on how rapidly the exudate dilutes the honey.

BOX 56-6

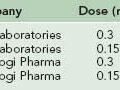

Recommended Empiric Oral Antibiotics for Bite Wound Prophylaxis and Treatment

| Antibiotic | Recommended Adult Dose | Recommended Child Dose* |

|---|---|---|

| Agent of Choice | ||

| A) Amoxicillin–clavulanate | 875/125 mg twice daily | 45 mg/kg per dose (amoxicillin component) twice daily |

| Alternate Combination Therapy: B or C (With Anaerobic Activity) Plus E, F, G, H, or I | ||

| B) Metronidazole | 500 mg three times daily | 10 mg/kg per dose three times daily |

| Or: | ||

| C) Clindamycin | 450 mg three times daily | 10 mg/kg per dose three times daily |

| Plus One of the Following: | ||

| D) Doxycycline | 100 mg twice daily | Not for use in children <8 yr old |

| E) Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole | 160/800 mg (1 DS tab) twice daily | 4 to 5 mg/kg (trimethoprim component) per dose* twice daily |

| F) Penicillin V potassium | 500 mg four times daily | 12.5 mg/kg per dose four times daily |

| G) Cefuroxime | 500 mg twice daily | 10 mg/kg per dose twice daily |

| H) Moxifloxacin | 400 mg once daily | Use with caution in children |

* Child dose should not exceed recommended adult dose.

Adapted from Endom EE: Initial management of animal and human bites. In Danzi DS, editor: UpToDate. Waltham, Mass, 2011, UpToDate.

Whenever possible, even in prehospital settings, wounds should be cleansed and irrigated thoroughly. Irrigation should be delivered with pressure equal to about 8 to 12 psi and debrided as effectively as possible. For some wounds that are not at high risk, attempting field closure is reasonable, and a loose closure with a dressing may help to decrease bleeding, prevent infection and make self-evacuation possible. However, in general, field closure of contaminated bite and claw wounds is not recommended. Further discussion of bandaging and wound-repair techniques may be found in Chapters 21, 22, and 23.

In addition to treating the bite victim, try to capture the offending animal for examination, if this can be done without risk of human injury in the process. Unusual behavior, such as unprovoked attack by a wild animal in broad daylight or a complete absence of fear of humans, should raise the suspicion for rabies (see Chapter 60). Live animal capture is optimal, but freshly killed animals are usually satisfactory for examination for fluorescent rabies antibody. Avoid damaging the animal’s head and brain (e.g., by gunshot or bludgeoning), because brain tissue is needed for analysis. Availability of the animal can eliminate the need for costly and uncomfortable rabies prophylaxis. If more than 1 hour will elapse before the animal can be transported to a hospital or public health department prepared to process the body for the determination of rabies, then refrigerate the body. For shipping, wrap the animal’s head and transport it in an insulated container with ice or ice packs. Do not use preservatives. Be sure to include the type of animal, details of the exposure, date of the animal’s death, victim information, and a description of the animal’s behavior in the report accompanying the specimen.304 An examination of the animal is not useful for most other diseases and will not help predict local wound infections. Therefore, use good judgment when deciding how much time and energy to expend on capture.

Evaluation and Treatment of Injuries: Hospital Care

Resuscitation with fluids and possibly blood products may be needed if there is extensive volume loss. When considering diagnostic imaging, the type of animal and its particular attack characteristics should be considered. Blunt trauma often accompanies penetrating injuries such as goring and trampling. Animal attack wounds classified as high risk for infection (Box 56-7) include deep puncture wounds, moderate or severe wounds with associated crush injury, wounds with areas of underlying venous or lymphatic compromise, wounds on the hands or in close proximity to a bone or joint, and bite wounds in compromised hosts (e.g., immunocompromised, absent spleen or splenic dysfunction, diabetes mellitus). Surgical consultation and hospital admission should be considered early in such cases.

BOX 56-7 Risk Factors for Infection from Animal Bites

High Risk

Location

Wound Management

Animal bites are not clean lacerations, and wounding may be compounded by crush injuries with devitalized tissue. All bites should be treated as contaminated wounds. Evaluate all victims of animal bites for blunt trauma and internal injuries, which may be less obvious than the bite wound (see Box 56-5). Internal organ, deep artery and nerve damage, and penetration of joints are all possible. Particularly in children, animal bites can penetrate vital structures, such as joints or the cranium.53,68 Radiographs may be employed whenever these injuries are suspected. A complete head-to-toe evaluation for trauma is advised in all but the most trivial and isolated bite injuries. Laboratory tests are of little use when evaluating animal bite injuries. Unless hematocrit is being assessed for evidence of blood loss, the complete blood cell count is not useful, because it is a nonspecific and unreliable gauge of infection. Definitive trauma evaluation and treatment are discussed in detail in Chapter 21.

Routine wound cultures obtained at the time of initial wounding do not reliably predict whether infection will develop or, if it does develop, the causative pathogens.135 Therefore, culturing an uninfected bite wound does not yield any useful data.49,60,135 If a bite wound appears infected, cultures and gram staining should be obtained before antibiotics are administered. It is useful to alert the laboratory technician that the culture is from a bite wound, because organisms such as Pasteurella multocida are often misidentified.

Many bite injuries are simple contusions that do not break skin. The infection potential of these injuries is low; superficial wound cleansing and symptomatic treatment of pain and swelling suffice. Treatment should include prompt and liberal application of ice or other cold packs during the first 24 hours. However, this is not beneficial for snakebite (see Chapters 54 and 55), and is obviously impractical in many locations.

When skin is broken, the risks of local wound infection or transmission of systemic disease are incurred. Infection can be caused by organisms carried in the animal’s saliva or nasal secretions, by human skin microbes carried into the wound, or by environmental organisms that enter the wound during or after the attack.225

Debridement removes bacteria, clots, and soil far more effectively than does irrigation.135 In addition, debridement is intended to create cleaner surgical wound edges that are easier to repair, heal faster, and produce a smaller scar. Topical antiseptic ointments (e.g., neomycin, bacitracin, polymyxin) are highly effective for promoting healing of minor skin wounds.146,206 Although topical ointments are appropriate for abrasions produced by animal bites, they may be less effective for punctures and sutured lacerations.

A sutured wound is covered by a simple, sterile, dry dressing to protect it from rubbing against clothing or repetitive minor trauma. Delayed primary closure requires that the wound be kept moist; this is usually done with a wet saline dressing twice daily until closure, which is generally planned for 72 hours after wounding.135

Wound Closure and Infection Risk Factors

Three major considerations govern the decision of whether to suture a wound: cosmetics, function, and risk factors. Cosmetic appearance virtually mandates suturing all facial wounds, which are usually low risk. Similar reasons may dictate closure of wounds on other visible portions of the body. Function is of critical importance for wounds of the hand, a high-risk area in which infection can have disastrous consequences. Thus, in general, all but the least complex hand wounds should initially be left open. Risk factors are many and complex, and provide a useful logical framework for making the decision of whether to suture, administer antibiotics, or undertake other treatments. For more information about surgical procedures, see Chapters 21 and 22.

The amount of time elapsed after wounding is a critical risk factor; the longer the interval, the more likely the chance for infection. After the first few hours, adequate wound cleansing is unlikely to be carried out. In developed countries, many victims are seen within hours of wounding, and the results are usually very good. In remote and undeveloped areas and countries, wounds commonly do not receive medical attention for half a day or more, thereby putting them into a high-risk category that may eliminate the possibility of primary repair. Certain species—including primates, wild cats, pigs, and large wild carnivores—seem to inflict infection-prone wounds. Wounds that involve crush injuries, puncture wounds, hands or feet, or affect a compromised host are at high risk for infection, and primary closure should only be attempted after careful consideration and with surgical consultation and concurrence in most cases. If primary closure is not chosen or deemed too risky, surgical consultation for a discussion of other options, including delayed primary closure or vacuum-assisted closure, is prudent.55,135

Many minimally contaminated bites can be safely sutured after proper wound preparation. Data suggest that carefully selected mammalian bite wounds can be sutured with approximately a 6% rate of infection.84 Two separate studies examining the risk of infection after primary closure reported rates of 7.8% (6 of 92 cases)214 and 5.5% (8 of 145 cases).84 The authors of the latter study concluded that the rate of infection after primary closure was acceptable, particularly if a good cosmetic outcome was needed.84

Bites of the Hand

Because hand bites are common and infection can be disastrous,334 the hand is considered at high risk for complications (see Box 56-7). The hand contains many poorly vascularized structures and tendon sheaths that poorly resist infection. The fascial spaces and tendon sheaths of the hand communicate with each other, and movement seals off the wound from external drainage and spreads bacteria and soil internally. Because of the unique anatomy of the hand, thorough irrigation of wounds is often impossible.

Data regarding hand wound infection have been collected mostly from experience with domestic dog and cat bites. From a retrospective study in Oslo, Norway, it was determined that nearly all hand bite wounds healed uneventfully when the wounds were left open, either without antibiotics or with penicillin after wound treatment.104 In another European center, the total infection rate was 18.8% in hand bite wounds; this rose to 25% when the hand wound was closed primarily. The average time from the injury to the first medical treatment was 11 hours in infected wounds and 2 hours in noninfected ones.7

Because of the high morbidity and permanent residual impairment that occurs with hand infections, treating them aggressively is best (see Box 56-5). Hand bite wounds should be irrigated, debrided if possible, and, in higher-risk wounds, initially left open.135,334 Small, uncomplicated lacerations can be repaired within 12 to 24 hours. The hand should be immobilized with a bulky mitten dressing in an elevated position, and the victim usually should be started promptly on antibiotics. Specialty consultation and follow up are mandatory for persons with established infection, and hospitalization should be considered. Persons who are not hospitalized should be rechecked daily until signs of infection clear. In the patient without initial evidence of infection, 5 days of splinting and oral antibiotics should suffice if no complications develop.62 Radiographic examination to search for fractures and imbedded foreign bodies should be considered for all significantly injured extremities.

Puncture Wounds

Punctures may occur as a result of biting, clawing, or goring. The infection rate is related to difficulty irrigating properly and degree of contamination, which is highest in bites. Puncture wounds can be contaminated with pieces of the victims’ clothing or shoes as well. Usually, attempts to irrigate narrow punctures simply result in rapid development of tissue edema from infused irrigant solution, which does not cleanse the wound. However, if the wound is large or can be held open wide enough to permit fluid to escape, irrigation is worth the effort. Large goring-type puncture wounds up to 20.3 cm to 25.4 cm (8 to 10 inches) deep from bison have a low incidence of infection when closed primarily after irrigation and debridement.96 For most smaller puncture wounds, irrigate or debride them as well as possible, suture only if cosmetic or functional considerations require it, and treat as having a high risk of infection.135 Use delayed primary closure liberally.

Facial and Scalp Wounds

Facial and scalp wounds tend to heal rapidly, with little risk of infection; in general, they may be sutured primarily, and do not require prophylactic antibiotics. Typical dog bites of the face and neck (including punctures) have an infection rate of only 3%, even when sutured.7,104,107,342 Generally the cosmetic closure of facial wounds is afforded by the lower incidence of infection. Standard of care in most cases is primary closure of an animal bite wound of the face.342

A major risk associated with facial and scalp wound victims of large carnivores is that the teeth can easily perforate the cranium, producing depressed skull fracture, brain laceration, intracranial abscess, or meningitis.78,260 In young children with such wounds, or in adult victims of large carnivore bites, computed tomography (or in the absence of computed tomography, skull radiography) should be routinely employed to look for evidence of perforation that would mandate immediate neurosurgical consultation and admission to the hospital.

Follow-Up Care

Assuming that the possibility of major or occult trauma has been ruled out, follow-up care for animal bites depends on the risk factors present (see Box 56-7) and the patient’s response to treatment. With only a superficial abrasion, infection is unlikely, and no return visit is needed. With an ordinary low-risk bite wound, one follow-up visit in 2 days to assess any infection will suffice. If the patient is very reliable and no sutures have been placed, a return visit may not be necessary. Infected wounds dictate much closer follow up, with the frequency depending on the wound’s response to treatment and the patient’s risk factors. In a high-risk wound or compromised patient, the initial follow-up visit should be made within 24 hours if the patient is not hospitalized.

Infection: Zoonoses and Rabies

Immense numbers of bacteria inhabit animals’ mouths and can be inoculated into a bite wound. Claw and scratch wounds may be contaminated with soil, urine, and feces. The exact pathogens vary depending on the biting species (Box 56-8). If inoculated in sufficiently large numbers, these microorganisms can cause localized cellulitis and abscess formation, the most common forms of infection. Wild animals also act as vectors for diseases, such as rabies, cat scratch fever, monkeypox virus, simian herpes virus, tularemia, hantavirus, tetanus, Q fever, and toxoplasmosis (see Chapters 59 and 60).

BOX 56-8

Common Bacteria in Animal Bites

| Dog Bites | Cat Bites | Large Reptiles (e.g., crocodiles, alligators) |

|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus speciesStreptococcus speciesEikenella speciesPasteurella speciesProteus speciesKlebsiella speciesHaemophilus speciesEnterobacter speciesDF2 or Capnocytophaga canimorsus Bacteroides speciesMoraxella speciesCorynebacterium speciesNeisseria speciesFusobacterium species | Pasteurella speciesActinomyces speciesPropionibacterium speciesBacteroides speciesFusobacterium speciesClostridium speciesWolinella speciesPeptostreptococcus speciesStaphylococcus speciesStreptococcus species | Aeromonas hydrophila Pseudomonas pseudomallei Pseudomonas aeruginosa Proteus speciesEnterococcus speciesClostridium species |

| Herbivore Bites | Swine Bites | Rodent Bites (i.e., rat-bite fever) |

| Actinobacillus lignieresii Actinobacillus suis Pasteurella multocida Pasteurella caballi Staphylococcus hyicus subspecies hyicus | Pasteurella aerogenes Pasteurella multocida Bacteroides speciesProteus speciesActinobacillus suis Streptococcus speciesFlavobacterium speciesMycoplasma species | Streptobacillus moniliformis Spirillum minus |

Data from Garth AP: Animal bites in emergency medicine. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/768875-overview.

Rabies

Rabies is discussed in detail in Chapter 60, so comments here are limited to brief remarks about epidemiology, assessment of risk in the bite victim, and local wound treatment.

The epidemiology of rabies varies widely in different parts of the world. In the United States, Western Europe, and Canada, wild animals are by far the main vectors of rabies, accounting for more than 88% of all reported cases from the past two decades.196 In India, 95% of rabies postexposure prophylaxis treatment is the result of bites from stray dogs.86 In recent years, rabies in humans has become an extremely rare disease in the United States, with only two cases occurring in 1997196 and one case in 2001.123 Since 1980, rabies-infected bats caused 58% of the human cases of rabies diagnosed in the United States.196 Of the more than 7437 cases of animal rabies reported in the United States in 2001, raccoons accounted for nearly 40% of the total. Foxes, bats, and skunks accounted for all but less than 1% of the remainder. Hawaii is the only state without any reported rabies.123 Foxes are the primary offenders in Europe; some countries have eliminated rabies in wild populations by using innovative vaccination programs.89

Because of local variations in animal vectors and endemics, consultation with the state or local health department is prudent before a decision is made to initiate rabies postexposure prophylaxis (PEP).196 Although the number of human cases has declined, about 18,000 people per year in the United States receive rabies PEP.134 In the rest of the world, virtually all rabies occurs in dogs. Worldwide, dogs account for 91% of all human rabies cases; cats 2%, other domestic animals 3%, bats 2%, foxes 1%, and all other wild animals only 1%.89,347 However, in the United States and Puerto Rico in 2004, 92% of all rabies cases were attributed to wildlife, with the majority being raccoons, skunks, and bats.196 It is important to note that 75% of animal injuries to travelers occurred in rabies-endemic countries, including Thailand, India, Indonesia, China, Nepal, and Vietnam.144 Each year in India, 25,000 humans die from rabies, and one-half million receive rabies vaccine.310 In Thailand, 50% of human rabies cases occur among children who are less than 15 years old.315 In Africa, Latin America, and most of Asia, dogs are the principal vector, although jackals are also a factor. In South America and Mexico, rabid vampire bats cause occasional human infection. During recent years, disruption of the natural ecology of vampire bats as a result of introducing humans and domestic animals to the rain forest has produced epidemics of rabies. In Israel, wolves and jackals are the chief vectors, and the mongoose prevails in Puerto Rico. In Eastern and Central Europe, the raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides) is an increasingly common vector.89

Thorough and rapid early treatment of wounds from suspected rabid animals may decrease viral load. Immediately cleanse all bite wounds and scratches with soap and water and a virucidal agent (e.g., povidone–iodine solution).302 Evaluate all persons exposed to a possibly rabid animal for rabies PEP. The CDC guidelines issued in 2009 recommend that, for previously unvaccinated persons, the entire dose of rabies immune globulin [20 IU/kg body weight] should be infiltrated at the wound site, if possible. In the United States, two types of rabies vaccine are currently available: human diploid cell vaccine and purified chick embryo cell vaccine. The chosen vaccine is given in 1-mL doses on days 0, 3, 7, and 14 after exposure. Rabies immune globulin should not be administered to previously vaccinated persons. Persons previously vaccinated should instead receive two 1-mL doses of vaccine (either purified chick embryo cell vaccine or human diploid cell vaccine) given on days 0 and 3.74 Further information about rabies pre-exposure prophylaxis and PEP is provided in Chapter 60.

Other Neurotropic Infections

Although Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is not caused by bites or wounds, oral transmission of this spongiform encephalitis has been reported to result from the regionally common practice of eating the brains of wild goats, pigs, or squirrels (even when cooked). CJD is characterized by progressive dementia, ataxia, and myoclonus, and is untreatable. It is caused by a virus also identified in the brains of domestic sheep and mule deer.187 Chronic wasting disease (CWD) is another transmissible spongiform encephalitis that is found in elk and deer in the Four Corners area of the United States (i.e., where Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah meet). Food-borne transmission of CJD has raised concerns that the species barrier (i.e., the difficulty an infectious disease encounters during transmission from one species to another as a result of structural protein differences between the agent and host) may not protect against CWD. In vitro conversion of CWD to a human infective form has been demonstrated, but further studies are needed. Between 2001 and 2003, six people—all of whom died—were identified as having a CJD variant. All were known to have consumed venison from CWD-endemic areas, although strong data linking CJD with exposure to CWD were lacking. The risk of transmission to humans, even in CWD endemic areas, remains extremely low.36 Mad cow disease is discussed in Chapter 59.

Indications for Wound Culture

Culture of fresh animal bite wound surfaces, whether judged quantitatively or qualitatively, is useless as a predictor of infection. Some of the pathogens of greatest concern (e.g., genus Eikenella) can take 10 days to grow out in culture, by which time most therapeutic decisions have been made. Other organisms (e.g., genus Pasteurella) are fastidious, hard to identify, and frequently missed by laboratory technicians, who rarely encounter them.150

If a wound is infected or if animal bite sepsis is suspected, obtain wound cultures to guide subsequent antibiotic therapy. In certain cases, cultures should be sent to reference laboratories, such as those in state health departments or at the CDC in Atlanta, Ga, because reference laboratories have successfully isolated more pathogens on identical samples sent simultaneously to both reference and local laboratories.314

Prophylactic Antibiotics

Currently, the weight of evidence does not support use of prophylactic antibiotics for wounds that are not high risk. Many animal bites, human and otherwise, are treated with prophylactic antibiotics, particularly bites to the hands or feet or if the victim is immune suppressed. Human-to-human bites, although outside the scope of this chapter, have similar risks for infection compared with other animal bites. A recent double-blind study of 125 people with superficial human bites showed no statistically significant difference in infection rates between antibiotic and placebo groups.52 A Cochrane Database Systems review of eight randomized controlled trials found no evidence that the use of prophylactic antibiotics is effective for cat or dog bites, except in the case of bites to the hand.225 The use of prophylactic antibiotics is advisable for wounds of the hand; the speed of development, frequency, severity, and complications of hand wound infections can be impressive.135,334 Persons with other risk factors may benefit from prophylactic antibiotics (see Box 56-6). These risk factors include prolonged time from injury to treatment; complex wounds with massive crushing; heavily contaminated wounds; wounds communicating with tendons; fractured bones or joint spaces; or medical conditions such as asplenia, diabetes mellitus, vascular insufficiency, and immune deficiency.

For bite wounds, treatment can begin only after wounding and bacterial inoculation; thus, antibiotics are never truly prophylactic. For major surgery, prophylactic antibiotics are of proved value only in carefully selected high-risk procedures and only if begun before surgery.329 Several controlled studies of dog bite wounds found no significant benefit for using prophylactic antibiotics to treat low-risk facial and scalp wounds.111,206 Other studies recommend the use of prophylactic antibiotics only for high-risk wounds or patients.104,107,155,334,342

To be most effective, prophylactic antibiotics must be administered early. The offending bacteria are already present in the wound when the victim is first seen. Therefore, bite victims who require early antibiotic treatment should be identified promptly, preferably during triage on entry to the treatment facility. The victim should receive immediate antibiotics by protocol; the intravenous route is by far the quickest. The current recommendation for duration of antibiotic prophylaxis is 3 to 5 days (see Box 56-6).

Therapy should be tailored to the largest variety of most likely pathogens for a particular type of bite. For most terrestrial mammals, the choice of antibiotic is based on experience with human, dog, and cat bites. However, with an alligator or crocodile bite, or other wounds incurred in freshwater, antibiotic choice should be directed against Aeromonas hydrophila174,226 (see Chapter 58).

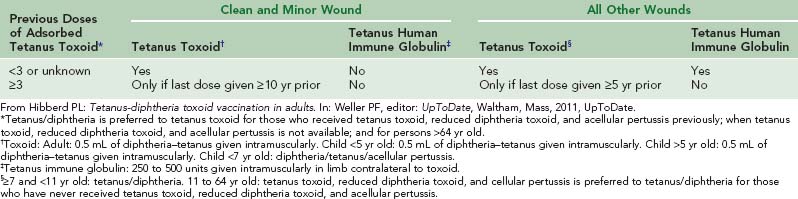

Tetanus Prophylaxis

In the United States, cases of human tetanus from animal bites exceed cases of rabies infection by a ratio of 2 : 1 each year.30 The spores of Clostridium tetani are ubiquitous in soil, on teeth, and in the saliva of animals; therefore, the risk of tetanus may be present from any animal injury that penetrates the skin. Rates of tetanus vaccination are highest in the developed world and fall dramatically in the developing world, with Somalia and Samoa having the lowest rates.346,348 For adults in the United States in 2007, the CDC reported that, out of a sample of 3525 people, 2.1% had received a tetanus booster (tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis) in the past 2 years, and the vaccination rate for tetanus during the prior 10 years was 57% (n = 1727).26,77 Because tetanus is preventable and many persons still do not receive tetanus immunoprophylaxis in accordance with guidelines, proper emergency prophylaxis against tetanus remains an important but often underaccomplished intervention (Table 56-4).

General Complications

Wound infection from animal bites should be treated like infection of any other traumatic wound. Elevate the wound, immobilize the affected part, remove sutures or staples if present, and provide antibiotic therapy (see Box 56-6). The 1999 Emergency Medicine Animal Bite Infection Study Group findings recommended that empiric treatment include a combined β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor antibiotic, a second-generation cephalosporin with anaerobic activity, or combination therapy with either penicillin and a first-generation cephalosporin or clindamycin and a fluoroquinolone.135,314 Additional studies recommend azithromycin, trovafloxacin, or telithromycin, which demonstrate good in vitro activity against unusual aerobic and anaerobic animal pathogens.150–152314 In 2002, a study showed that garenoxacin, a des-fluoro(6) quinolone, was very active against 240 aerobic and 180 anaerobic isolates from bite victims. It inhibited 403 of 420 (96%) isolates, including those of Moraxella spp., CDC group EF-4, Eikenella corrodens, all Pasteurella spp., and Bergeyella zoohelcum. Fusobacterium russii and 6 of 11 Fusobacterium nucleatum isolates of animal bite origin were resistant.153

Extremely rare pathogens can cause infection (see Box 56-8). Culture of debrided tissue is the only reliable identification technique, and sensitivity testing may take weeks. In 2002, a 7-year-old girl developed a wound infection as a result of a tiger bite; DNA sequence analysis revealed that one of the causative organisms was a previously undescribed subspecies of Pasteurella multocida, which the authors designated “Pasteurella multocida subspecies tigris.”63 This organism is usually sensitive to ciprofloxacin, cefoxitin, and perhaps rifampin.266 A diabetic patient developed tenosynovitis caused by Mycobacterium kansasii after an accidental bite by his pet dog,305 and Bergeyella zoohelcum has been reported as a fastidious species that is difficult to culture from patients with infected cat bites.294

Septic Complications

Bacteremia and sepsis, although theoretic risks with any animal bite pathogen, have so far been reported with only a limited number of species.9,133,197,260 Clinical manifestations include cellulitis, endocarditis, meningitis, pneumonitis, Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome, renal failure, shock, and death. Purpuric lesions are seen in one-third of cases and may progress to symmetric peripheral gangrene and amputation. House cats are an increasing source of human plague in the Southwest United States. Since the onset of the human immunodeficiency virus epidemic, Rochalimaea infection (bacillary angiomatosis) has also become more prominent, and is closely associated with exposure to cats. Although sepsis after an animal bite incident is reported more often among immunosuppressed patients (e.g., there was a case of fatal Pasteurella dagmatis peritonitis and septicemia in a patient with cirrhosis188), there are reports of fatal cases of purpura fulminans with gangrene, sepsis, and meningitis caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus among previously healthy patients after dog bites. 109,204

Allergic Reactions

Up to 11% of laboratory workers have allergic reactions to laboratory animal dander, hair, or urine.343 One case of proved hypersensitivity to rat saliva after a bite has been reported.157 The patient was subsequently proved to be allergic to the saliva (presumably to saliva proteins) and not to other portions of the rat. The bite produced lymphangitic swelling and itching that subsided within 24 hours. Two cases of anaphylaxis after dwarf hamster bites have also been reported.241

Psychiatric Consequences of Animal Attacks

Victims of traumatic or life-threatening events may develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This syndrome has been recognized by the authors as a result of wild animal attack, and is rarely reported in the scientific literature.108 After physical recovery from an attack, the victim may be plagued by recurrent nightmares and flashbacks of the event and may have an aversion to outdoor travel. Violent and multiple attacks or those associated with deep bites have a higher probability of causing PTSD symptoms.262 Critical incident stress debriefing and post-trauma intervention counseling may be important aspects of care for victims of animal attack.108 PTSD has been described among children who are victims of dog bites.262 In a 2004 study, 12 of 27 pediatric patients developed either complete or partial PTSD as a result of dog bites.262

Wild Animal Attacks

Canines

Coyotes

Coyotes (Canis latrans) have not only survived the onslaught of civilization in the United States but have thrived and multiplied. Perhaps as a result, more and more coyote attacks on people have been reported, even in urban areas such as Los Angeles.16,64,177 Most of these incidents occurred in Southern California near a suburban–wildland interface. One study done in 1982 was intended to show the coyote density at such a location. Traps were set for the animals within a one-half mile radius of a particular residence, and 55 coyotes were trapped during an 80-day period.176 Between 2004 and 2007, 541 coyotes were removed on average from Illinois; 312 were from the Chicago area alone. It is estimated that there are 1250 coyotes in the suburban area surrounding Washington, DC.311

Between 1998 and 2003, there were 41 coyote attacks on humans in California, and most were unprovoked; it appears that nonrabid coyotes are becoming more aggressive with humans.79 Rabies is less prevalent among coyotes and foxes with the advent of an oral rabies vaccine for these species.295

Attack incidents are typically preceded by a sequence of increasingly bold coyote behaviors. These may include nighttime coyote attacks on pets; sightings of coyotes in neighborhoods at night; sightings of coyotes during the morning and evening hours; attacks on pets during daylight hours; attacks on pets on leashes; chasing of joggers and bicyclists; and midday sightings of coyotes in the vicinities of children’s playgrounds318 (Figure 56-2, online).

FIGURE 56-2 A hiker at a trailhead bitten on the foot by a coyote while napping.

(Courtesy Luanne Freer, MD.)

Since the 1970s, more than 100 coyote attacks on humans have been recorded in Southern California, with one-half of these incidents involving children who are 10 years old or younger.79 There is one well-documented fatality of a child in 1981, who, despite being rescued by her father, died of blood loss and a broken neck.79 A 5-year-old boy in Middletown, New Jersey (about 64.4 km [40 miles] from New York City) was bitten by a coyote and required 46 stitches to his head.311 A 19-year-old woman was killed by two coyotes (likely coyote–wolf hybrids) in Nova Scotia, Canada while hiking on a trail in October 2009; the woman died of blood loss from multiple bite injuries, and, although one of the animals was wounded, neither coyote was captured.157

The safe environment provided by a wildlife-loving public, which rarely displays aggression toward coyotes, is considered a major contributing factor to the increasing numbers of attacks.79 There has been an increase in reports of coyote attacks in national parks by animals that are subsequently captured and found to be disease free.64

A coyote bite should be treated as a dog bite with respect to antibiotic choice and closure issues; if the animal cannot be captured and examined, rabies prophylaxis should be undertaken. Coyotes have been identified as the reservoir for the human pathogen Bartonella vinsonii sub sp. berkhoffii.80

Wolves

The gray wolf (Canis lupus), also known as the timber wolf, is the largest wild member of the Canidae family (Figure 56-3). There are an estimated 7000 to 11,200 gray wolves in Alaska and more than 5000 in the lower 48 states. Worldwide, the wolf population is estimated at 200,000 in 57 countries.106

Wildlife experts suggest that attacking wolves are habituated to humans and human food sources. However, most unhabituated wolves are traditionally timid. Historically the majority of predatory attacks occurred during the summer months, and victims were predominantly women and children. Predatory attacks by wolves against humans tend to occur in clusters, indicating that human killing is not normal wolf behavior but rather specialized behavior that single wolves or packs develop and maintain until they are killed.335

Throughout Europe and Asia, wolves have well-documented histories of cunning behavior, pack attacks, and human killing.209 In one Indian state, 100 children were injured and 122 killed between 1980 and 1986.274 Between 1840 and 1861, Russia reported 273 nonrabid wolf attacks, resulting in the deaths of 169 children and 7 adults.194 North America has fewer verified cases, although recent research indicates 80 events in Alaska and Canada during which wolves closely approached or attacked people (there were 39 cases of aggression by apparently healthy wolves and 29 cases of fearless behavior by nonaggressive wolves).208,224 Five wolf attacks on humans occurred within a 12-year period in Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario, Canada, and a kayaker was pulled from his sleeping bag by wolves in British Columbia, Canada.208 In 2005, a hiker in Northern Canada was eaten by wolves, although he likely died of other causes.121,145 Most recently, in March 2010, a woman was killed by wolves in Alaska in what is thought to be the first known fatal attack by wolves in the United States in modern times.235 Villagers in the area had noted increasing aggression from local wolves preceding the attack; wolves are the only large predator in the region, and had been entering the villages at night and frequenting the edges of settlements.

A substantial number of attacks by rabid wolves in Iran over a 10-year period provided the clinical population upon which the human diploid cell vaccine for rabies was tested.24 The reintroduction of wolves to wild habitat in the Yellowstone ecosystem and Idaho in 1995 has resulted in the successful proliferation of many new wolves. However, there has not yet been a negative human interaction since their release.158

Comparison of victims of fatal attacks by domestic dogs and wild wolf packs reveals distinct differences in bite-mark patterns; the necks and faces of domestic dog attack victims were the primary sites of injury, whereas a wolf-pack victim was spared damage to the neck but had facial tissue destroyed postmortem. Most punctures are found on the ventral aspect of victims of domestic canine attacks as opposed to dorsal punctures among victims of wild or feral canines. Wild canine bites involve characteristic crushed and macerated tissue and should be debrided carefully. Other treatment should follow the same guidelines as for victims of domestic canine attack. It is speculated that most wounds are attributable to the dominant animals of a pack. Differences in bite-mark patterns may be attributed to differences in genetics, training, breeding, socialization, and impetus of attack between wolves and dogs.344

Foxes

Most human attacks by foxes are inflicted by rabid animals; fox bites have caused eyelid lacerations among children who are sleeping in tents and leg punctures among adults.195,313,327 One child died of rabies from fox bites despite appropriate PEP.313 A rabid gray fox bit several people during a single afternoon in 2008 in Arizona.14 Foxes can cause more puncture wounds than other canines, making their bites more prone to infection. Oral vaccination of fox populations has led to a decline in the number of rabid animals.295

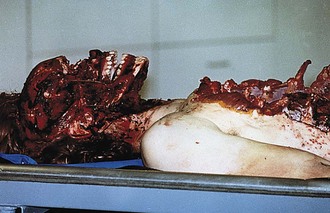

Hyenas

Hyenas have tremendously strong jaws, with a bite force of 1000 psi, and can leave teeth marks in forged steel (Figure 56-4). They have been known to amputate limbs and behead small children.210 The hyena frequently attacks humans in Africa, and, in certain areas in which locals leave dead or dying people in the bush for predators to eat, hyenas become accustomed to the taste of human flesh. Hyenas forage around campsites and villages, and are wary of awake people. During the summer months, when Africans sleep outside of their huts, many are assaulted with one clean, massive bite that removes the face or the entire head. Young children have been dragged from their huts while sleeping when a family member leaves briefly without latching the door, and it is common for the hyena to injure or amputate the thumb of a sleeping victim as it drags the victim (by the thumb) to a more convenient place for consumption.2 Campers are frequently bitten on the face or limbs while they sleep at night, particularly if they have left food nearby. Victims usually survive but are massively disfigured. In some parts of Africa, the hyena is a more consistent maneater than the leopard or lion.

Other Canines

In Australia, during a 5-year period, dingoes that had been habituated to people were responsible for 224 attacks on humans that required medical treatment and for several fatal attacks on children.272 However, dingoes are disappearing from Australia quickly183 and in general pose little threat to humans. Jackals are found in Africa, Southeast Europe, and Asia. Jackal attacks are typically only from rabid animals. In Sri Lanka in 2007, one village reported four different attacks by a jackal that was acting abnormally.281 In many areas of the developing world, the main concern with jackals is transmission of rabies to domestic dogs. Two other canines that traditionally hunt in packs are the cape hunting dog of Africa and the Indian “devil dog.” Although both are feared in their respective environments, typically they do not deliberately attack humans.

Felines

Big cats typically attack from behind and bite the neck and occiput of their prey in an attempt to maneuver their canine teeth between the victim’s cervical vertebrae and into the spinal cord.95,282,333 The goal of rapidly paralyzing the prey is also accomplished by a violent shake of the cat’s head, which fractures the cervical spine. In a study of fatalities from jaguar attack, 77% of victims were bitten on the nape of the neck, and one-half of the bites were made to the base of the skull.95 In 20% of cases, the killing bite was to the head, with at least one canine piercing the skull or ear canal. Cheetahs prefer to attack the throats of their prey, crushing the larynx and strangling the victim; this method is also used by lions and leopards.209 In addition, big cats claw their prey and produce deep, parallel, incised wounds. Several victims have died of exsanguination without evidence of strangulation or cervical spine injury.95,282 Because of the growing propensity for people in developed countries to keep exotic animals as pets or raise them for profit for hunting purposes, injuries by big cats can occur anywhere.

Wound care is the same as for other species, with special attention paid to evaluation for major internal injury. In particular, observe for penetration of deep structures of the cranium and neck, and rule out injuries of the cervical spine and deep cervical vessels (see Box 56-5).95 One victim with an apparently trivial puncture wound after a bite to the neck from a pet cougar was discharged from the emergency department.190 Within hours, her voice was hoarse; on return, she recalled that the cougar had shaken her in its jaws when it bit her, and air was found in the prevertebral and retropharyngeal spaces on radiographic examination.

If a big cat is encountered in the wild, humans should not run but instead stand their ground; running will provoke an instinctive response from the cat to chase. Humans should make themselves look as large as possible, such as by raising arms and jackets over the head. Shouting and acting aggressively may deter an attack. Humans should not turn their backs or crouch when confronted by a big cat. However, as with other large animals, fighting back once an attack has begun may cause a cat to abandon the attack.85

Like domestic cats, big cats usually carry Pasteurella as normal flora. Because of the deep penetration of their large teeth, Pasteurella septic arthritis, meningitis, and other serious deep infections can occur.143 Cat-scratch disease (Bartonella henselae), which is common with domestic cats, may also be transmitted by wild cats; it has been isolated in puma and bobcat populations in the Americas.90

Tigers

Tigers are a major threat to human life in the cats’ native regions.222 Although the number of tigers in the world is dwindling rapidly, historically they have been the number one animal killer of humans (see Table 56-2). Nonetheless, man-killing almost invariably results from stress (e.g., wounds, old age) or lack of natural prey and habitat that forces the animal to prey on humans. A tiger subsisting solely on human meat would have to kill approximately 60 adults per year; documented cases in selected regions have approached this rate over periods of up to 8 years.

Unlike leopards, tigers rarely enter human settlements, preferring to remain on the outskirts. Maneating tigers in India between 1906 and 1941 ate an estimated 125 persons each, and one had killed 436 persons. However, compared with lions, tigers are not thought to become exclusive man-eaters; rather, they are opportunistic man-eaters in lieu of plentiful natural prey, and tiger biologists hypothesize that these animals have become unafraid of man.222

Over the last five centuries, an estimated 1 million people have been eaten by tigers. During the nineteenth century, the tigers’ toll in India averaged 2000 victims per year. From 1930 to 1940, the annual number never dropped below 1300. During the late 1940s, this rate dropped to 800 per year, where it remains. In other regions, rapid habitat loss as a result of climate change has caused an increase in tiger attacks in the Sundarban Islands of Northern India. In this region, seven fisherman were reported to have been killed by tigers during the first half of 2008.125

Adult tigers are so powerful that their human victims are often killed instantly. It is not unusual for a limb to be severed with a single bite,117,205 and a tiger’s swiping blow to the human head can cause skull fracture.270 Like many big cats, tigers typically strike without warning from behind, biting the head and neck and often shaking the head violently so that it severs the victim’s spinal cord.193

Lions

The lion (Panthera leo) is grouped with the four big cats of the genus Panthera (Figure 56-5). Despite their appearance and reputation, lions are not as feared or respected by experienced hunters as are tigers (Figure 56-6). Lions are primarily scavengers, making fewer original kills than hyenas do.

Conversion to maneating has been blamed on drought, famine, and human epidemics in which large numbers of corpses are abandoned in the bush. Although some consideration has been given to the theory that infirm lions are more prone to maneating behavior and although tooth decay may explain some incidents, prey depletion in human-dominated areas is a likelier cause of lion predation on humans.256 In addition, there is an historic predator–prey relationship between Panthera and primate genus members, which suggests that maneating behavior is neither unusual nor aberrant.261 Lion attacks tend to cluster during harvest times and during periods when prey is scarce.254 Wounded or sorely provoked animals, usually in dense brush (Figure 56-7), kill the majority of hunters who succumb to lions.

American and Tanzanian scientists report that maneating behavior in rural areas of Tanzania increased from 1990 to 2005. At least 563 villagers were attacked and many eaten over this period.254 Lions are estimated to eat 300 to 500 Africans per year, and rank second to tigers among man-eaters. During the late 1930s and early 1940s, three generations of a single pride in Tanzania were credited with between 1500 and 2000 human kills. A protected population of 250 Asiatic lions in India has attacked 193 humans, killing 28 between 1977 and 1991; biologists credit drought and lion baiting for tourist shows for this carnage.283

Leopards

Leopards are the smallest of the four big cats in the genus Panthera (Figure 56-8). Like the other big cats, leopards suffer from a loss of habitat and hunting pressure that have reduced their range. Originally inhabiting wild land from Korea through Africa, leopards now exist primarily in sub-Saharan Africa, with isolated pockets across the Asian subcontinent. However, leopard numbers still top all others in the genus Panthera.

Most attacking leopards have been previously wounded or attacked by a dog; when wounded, trapped, or cornered, a leopard is unpredictable and ruthless, attacking the first person within striking distance. Unmolested and in normal health, the leopard is a shy and nervous animal with a marked fear of humans. Unlike a lion or tiger, the leopard relies on fast claw work and biting. Like the jaguar, the leopard may go for the neck (in an effort to sever the spinal cord) or attempt disemboweling by raking at the victim’s abdomen with its claws. The leopard seems inclined to retreat when much resistance is offered; the chance of surviving a leopard attack is higher than the chance of surviving a lion or tiger attack. There is a documented report of a man armed only with a screwdriver who fought and killed an attacking leopard.198,199 Before the era of antibiotics, three-fourths of people mauled by leopards died from wound infection; however, modern morbidity from these attacks is estimated to be less than 10%.25,92

Mauling by leopards is much more common than killing; estimated casualties are 400 per year, mostly in Africa. The leopard does not often turn into a man-eater; when it does, it attacks mainly children or sick adults. In the state of Bihar in India, leopards ate 300 people between 1959 and 1960.92 The maneating leopard of Rudraprayag in India killed 150 people between 1918 and 1926. Becoming increasingly bold, it eventually took its prey by banging down doors, leaping through windows, or clawing its way through the walls of mud huts. The Panar leopard killed more than 400 people after injury by a poacher made it unable to hunt normal prey.169 Like maneating lions, maneating leopards completely change their normal hunting patterns when the prey becomes exclusively human.

Jaguars

The jaguar is last of the four big cats in the genus Panthera and the only one native to the Americas; it is not known to be a man-eater. However, attacks do occur. In February 2007, a zookeeper in the United States was mauled to death by a jaguar.227 In January 2009, a Maryland zoo worker at a private zoo was badly mauled.139 There have also been undocumented reports of jaguar attacks in the jungles of South and Central America.

The jaguar has an exceptionally powerful bite, even relative to other big cats. It employs a variation of the deep throat bite and suffocation technique employed by other Panthera. Using its canine teeth, it pierces directly through the temporal bones of the skull between the ears of its prey, piercing the brain.124

Cougars

The North American cougar (Puma concolor), also called mountain lion or puma, is a clever and shy cat. It is the most widely distributed large animal on the American continent, and the second biggest cat in the Western hemisphere (after the jaguar), although it is more closely related to smaller cats. Cougars are encroaching with increasing frequency into populated areas of the western United States; this is probably because of human expansion into the wilderness and an increased population of protected cougars.192 The current cougar population in Oregon is estimated to be more than 5700,249 and the U.S. population of cougars is estimated at 16,000.321 Humans live, exercise, or picnic in cougar country with increasing frequency.309 Thus, modern suburban dwellers (who are typically ignorant of wild animal behavior) are now in regular close contact with cougars in their homes and parks, whether they know it or not.

In North America between 1890 and 2004, there were 88 confirmed cougar attacks on humans, resulting in 48 nonfatal injuries and 20 human deaths.13 More people have been attacked since 1975 than during the entire previous century,5,21,131 and most attacks occurred in the Western United States and Canada. Throughout the United States, cougars ranked sixteenth in recent years as an animal-related cause of deaths, just behind jellyfish and goats.275 In California, no attacks occurred from 1925 until 1986, when two children were attacked in a regional park in Southern California,190 and the first cougar attack in 34 years occurred in New Mexico in 2008.239

Victims jogging and biking may evoke a predatory response. Young animals that are forced out by adults and must find their own territory are the most frequent attackers of humans,192 and children tend to be the preferred victims: 64% of attacks and 86% of fatalities involve children.35,182,186 There has been only one alleged report of a cougar as a primary man-eater, but cougars commonly consume victims of their attacks (Figure 56-9).32,282

The cougar hunts like a domestic cat: crouching, slinking, sprinting, pouncing, and then breaking the neck of the prey. Neck, head, and spinal injuries are common and sometimes fatal. Like many potentially dangerous wild animals, the cougar can often be scared off by the victim’s aggressive behavior, even after the attack has begun.170 In 2002, a man fought off and killed an attacking cougar with a 7.5-cm (3-inch) pocketknife.328

Bobcats

Although it is unusual, bobcats occasionally attack humans. In most cases, the bobcat is rabid and unusually aggressive. In 2000, a Minnesota woman reported suffering puncture wounds to her hand and arm that were consistent with the bites of a bobcat. Another woman was the victim of a witnessed bobcat attack in Big Bend National Park.44 In this case, although experts believed that the animal was behaving normally, the victim was empirically treated for rabies exposure. A hunter sustained injury to the eye and ocular adnexa requiring surgical repair after a bobcat attack.173 Two people were attacked by a rabid bobcat in 2008 in Arizona while hiking in the mountains, suffering puncture wounds and scratches; the bobcat was described as unusually aggressive, and pursued the couple up a hill.132 A man in Florida reported being attacked by a rabid bobcat on his front porch, where he was clawed and bitten until he managed to strangle the animal.215

Primates

The Primates order is divided into two main groups: the prosimians, which have characteristics most like those of the earliest primates, and the simians, which is comprised of monkeys and apes. Simians are further divided into the New World monkeys of South and Central America and the Old World monkeys of Africa and Southeastern Asia (Figures 56-10 and 56-11; Figure 56-11, online).

Monkeys and other primates inflict vicious bites that virtually always become infected, despite use of prophylactic antibiotics.154 Although in developed countries human–primate conflict is a problem limited to laboratory workers, in tropical developing countries, large apes (e.g., baboons) are both at large and often aggressive. Weighing up to 40.8 kg (90 lbs), a large baboon can be dangerous and lethal, particularly when the animal has frequent contact with humans and loses fear of them. There are multiple reports of baboon attacks in South Africa against visitors, typically when the baboon is foraging for food.61 There have been numerous recent reports of packs of wild monkeys driven out of the jungle by hunger, attacking humans who get in the way of food sources.278,285,307 Feral macaque populations have been reported in regions of Texas and Florida.252

Monkeys often bite hands and have been known to amputate parts of fingers. A literature review revealed 132 cases of simian bites in which Bacteroides, Fusobacterium species, and Eikenella corrodens were isolated from some of the wounds.154 Three victims of simian bites with infected wounds grew diverse bacteria, including β-hemolytic streptococci, enterococci, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Enterobacteriaceae.154 At the present time, simian bites should be considered high risk and treated in the same manner as human bites.

Old World macaque monkeys (i.e., rhesus macaque, cynomolgus, and other Asiatic macaque monkeys) are often infected with simian herpes virus (B virus). Transmission to humans is rare, but the risk is real, especially for animal control and laboratory workers.114,240 As with rabies, local wound treatment may be important; of 61 persons bitten by probably infectious monkeys who received wound cleansing with cetrimide and iodine solution, none became infected.320 The mortality rate for B virus is 80% without treatment; through 2002, there were 26 documented cases of B virus infection in humans and 16 deaths. Twenty of the victims developed some degree of encephalitis. The most recently documented case occurred in 2008 and involved a woman who was bitten by a vervet monkey in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in Africa (see Chapter 59).244,331

The wild gorilla, despite its reputation and appearance, is shy and avoids humans. Although it may charge in defense, it seldom attacks, and can be easily confronted and forced to retreat. When a gorilla attacks, it typically takes one bite and runs. In Africa, gorillas are responsible for two or three attacks per year, none of which is fatal, and few of which are severe. Chimpanzees occasionally attack humans, but usually only if provoked or cornered. Rare instances of chimpanzees eating children and women have been reported. The baboon is responsible for one to two attacks per year, almost all in South Africa; these are usually by pets. Occasionally, maneating has been reported. The incidence of hunting and meat eating by these animals has increased over the last century, perhaps paralleling the evolution of humans into hunters and meat eaters.92

Herbivores and Ungulates

Wild Swine

Wild pigs are more likely to inflict injury than their domestic counterparts. With a population of over one-half million roaming the French countryside, wild pigs cause crop loss and occasionally gore and bite humans.213 A typical wild boar attack can result in multiple penetrating injuries to the lower part of the body caused by the boar’s tusks (Figure 56-12, online). In an unusual incident, an Indian laborer was gored from behind by a boar, which then returned and attacked his head while he was on the ground; the man died of severe craniofacial injuries.216,292

Domestic pigs can easily become feral, and such populations often revert to the behavior and appearance of a wild boar. In the United States, feral pigs—some weighing up to 181.4 kg (400 lbs) with 10.2-cm (4-inch) tusks and prolific breeding qualities (i.e., some litters of up to 19 have been reported)—are experiencing explosive population growth. More than 1.5 million wild swine roam the state of Texas, and motor vehicle collisions as well as attacks on humans are increasing.54 As of 2008, it was estimated that the population of 4 million feral hogs caused approximately $800 million worth of property damage per year in the United States.51 Swine wounds should be treated as high risk for development of infection, warranting broad-spectrum prophylactic antibiotics (perhaps parenterally) and close follow up if the victim is not admitted to a hospital.

African Buffalo

Known as one of the “big five” (i.e., the five most difficult African animals to hunt on foot: buffalo, lion, elephant, black rhino and leopard), African buffalo (Syncerus caffer) gore and kill more than 200 people each year. The unprovoked African buffalo usually does not attack. However, when provoked (i.e., shot or cornered), it charges, is difficult to avoid or stop, and can hook the victim 3 m (10 feet) into the air with its horns (Figure 56-13). Buffalo that charge humans are usually old solitary bulls that have left the safety of the large herds, most often because of wounds from poachers’ snares or spears, or from lion attacks. The buffalo is also wily and intelligent; wounded buffalo may lie in wait for trackers, or may double around and come up behind hunters on the trail, often with fatal consequences for the humans (Figure 56-14, online). One hunter was treed by a buffalo but could not get his feet high enough to keep them clear of the animal; the buffalo repeatedly hooked the man’s feet with his horns, eventually cutting them so that the hunter bled to death while still hanging in the tree. In another anecdotal series, a single buffalo injured several humans in one day; all of the wounds were impaling injuries through the anus.2

When the victim is prostrate, the buffalo gores into the ground with its horns and the heavy horny boss across its forehead and then whips its head from side to side, disemboweling the victim with the sharp horn tips. The horns are always covered with mud, so goring wounds may be heavily contaminated. However, victims who do not have major traumatic injuries generally do well.291