Bites

A wide variety of bites are seen in children. It is estimated that more than 1 million children are treated annually for bites (Table 12-1).1 In this chapter we concentrate on bites of interest to the surgeon. The reader is referred elsewhere for discussions of management of venomous stings and injuries from marine life and general details of wound management.

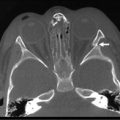

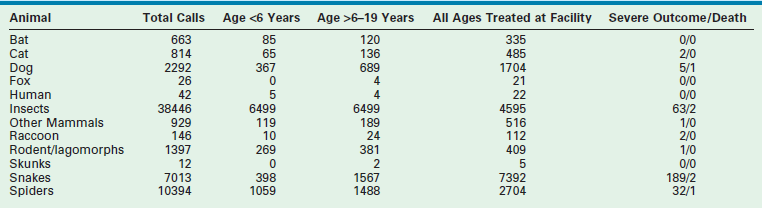

TABLE 12-1

Bites and Envenomations to Humans: Calls to Poison Centers in 2010

Data from Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, et al, editors. 2010 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers National Poison Data System (NPDS): 28th Report. Clin Toxicol 2011;49:910–41, Appendix.

Tetanus

The Gram-positive anaerobic organism Clostridium tetani is the causative agent for tetanus, a severe and often fatal disease. In 2009, there were a total of 18 cases (zero under 14 years of age) reported in the USA.2

There has been a low incidence rate of tetanus since a peak of 102 cases in 1975. Mortality from tetanus is associated with co-morbid conditions such as diabetes, intravenous drug use, and old age, especially when vaccination status is unknown. Infection can occur weeks after a break in the skin, even after a wound has seemed to heal. The ideal anaerobic surroundings allow spores to germinate into mature organisms producing two neurotoxins: tetanolysin and tetanospasmin.3 The latter is able to enter peripheral nerves and travel to the brain, causing the clinical manifestations of uncontrolled muscle spasms and autonomic instability. The incubation period varies from as short as two days to several months, with most cases occurring within 14 days.4 In general, the shorter the incubation period, the more severe the disease and the higher the fatality risk.

All wounds should be cleaned and debrided. Symptomatic and supportive care includes medications such as benzodiazepines to control tetanic spasms and antimicrobials for infection. Metronidazole (oral or intravenous, 30 mg/kg/day, divided into four daily doses, maximum 4 g/day) is the preferred antibiotic because it decreases the number of vegetative forms of C. tetani.5 An alternate choice is parenteral treatment with penicillin G (100,000 U/kg/day every four to six hours, not to exceed 12 million units/day) for ten to 14 days. Human tetanus immune globulin (TIG) is administered to adults and adolescents as a one-time dose of 3000–6000 units intramuscularly. Some experts recommend that children receive 500 units to decrease the discomfort from injection.5 Infiltrating part of the dose locally is controversial. Tetanus prevention in a potentially exposed patient depends on the nature of the wound and history of immunization with tetanus toxoid (Table 12-2).

TABLE 12-2

Wound Tetanus Prophylaxis Guideline

| Vaccination History (Td) | Clean/minor Wounds | All Other Wounds |

| ? or <3 doses | Td or Tdap—No TIG | Td or Tdap—TIG |

| ≥3 doses | Td or Tdap—No TIG if ≥10 years since last dose | Td or Tdap—No TIG if ≥5 years since last dose |

Data from American Academy of Pediatrics: Tetanus (lockjaw), Bite Wounds. In Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, Long SS (eds): Redbook: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL, American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009, pp 187-191, 655–60.

Cat, Dog, Human, and Other Mammalian Bites

Children are frequent victims of mammalian bites. The most common complication from bites is infection: cats, 16–50%; dogs, 1–30%, and humans, 9–18%.6 When the bite is from a cat, dog, or other mammal, the most common infectious organisms are Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Actinomycetes, Pasteurella species, Capnocytophaga species, Moraxella species, Corynebacterium species, Neisseria species, Eikenella corrodens, Haemophilus species, anaerobes, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and Prevotella melaninogenica.5,7,8 Human bites are a potential source not only for bacterial contamination but also for hepatitis B and, possibly, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.9

Recommendations for bite wound management are presented in Box 12-1. Evidence-based medicine studies concerning whether to close wounds are not conclusive. Distal extremity wounds, especially hand/fist to teeth, are at higher risk for infection. Whether minimal risk wounds require prophylactic antimicrobial therapy is also controversial. Antibiotics started within eight to 12 hours of the bite and continued for two to three days may decrease infection rate.5 The oral drug of choice is amoxicillin-clavulanate. For penicillin-allergic patients, an extended-spectrum cephalosporin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole plus clindamycin should be used.5

Rabies and Postexposure Prophylaxis

Rabies is a viral disease usually transmitted through the saliva of a sick mammal (e.g., dogs, cats, ferrets, raccoons, skunks, foxes, bats, and most other carnivores). The majority of reported cases in the USA are caused by raccoons, skunks, foxes, mongooses, and bats. Small rodents such as rats, mice, squirrels, chipmunks, hamsters, guinea pigs, rabbits and gerbils are almost never infected with rabies. Over the past decade, cats have been the most common domestic animal with rabies. Rabies-related human deaths in the USA occur one to seven times per year since 1975. Modern prophylaxis has proven nearly 100% successful. Worldwide, fatalities are about 40,000–70,000. The rabies virus enters the central nervous system and causes an acute, progressive encephalomyelitis from which survival is extremely unlikely. The human host has a wide range for the incubation period from days to years (most commonly weeks to months).

Prophylactic treatment for humans potentially exposed to rabies includes immediate and thorough wound cleansing followed by passive vaccination with human rabies immune globulin and cell culture rabies vaccines, either human diploid or purified chick embryo.10–12 Many factors help determine the risk assessment in deciding which patient benefits from post exposure prophylaxis and which regimen should be given. The risk of infection depends on the type of exposure, surveillance, epidemiology of animal rabies in the region of contact, species of animal, animal behavior causing it to bite, and availability of the animal for observation or laboratory testing for the rabies virus. The final decision for treatment with vaccines is complex. Therefore local, state, or CDC (Centers for Disease Control) experts are available for assistance. There is no single effective treatment for rabies once symptoms are evident.

Spider Bites

There are about 40,000 species of spiders that have been named and placed in about 3000 genera and 105 families.13 In regard to medically relevant spiders, few are known to cause significant clinical effects. In 2010, about 11,000 calls were made to USA Poison Control Centers (PCC) regarding spider bites.1 It is rare that a spider bite requires surgical care. Few spiders have been shown to have the ability to bite humans because their fangs cannot pierce the skin. The two most medically important spiders in the USA are Sicariidae (brown spiders) and Lactrodectus (widow spiders).

Brown Recluse Spiders

Loxoscelism is a form of cutaneous–visceral (necrotic–systemic) arachnidism found throughout the world with predilection for North and South America.14 There are four species of brown spiders within the USA that are known to cause necrotic skin lesions (Loxosceles deserta, L. arizonica, L. rufescens, and L. reclusa). L. deserta and L. arizonica can be found in the southwestern USA L. reclusa is the most common species associated with human bites. It is usually found in the south central USA, especially Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Tennessee, and Kentucky.15 Spiders can be transported out of their natural habitat but rarely cause arachnidism in nonendemic areas. L. reclusa is tan to brown with a characteristic dark, violin-shaped marking on its dorsal cephalothorax, giving it the nickname ‘fiddleback’ or ‘violin’ spider. The spider can measure up to 1 cm in total body length with a 3 cm or longer leg span (Fig. 12-1). These spiders only have three pairs of eyes whereas most spiders have four pairs.

FIGURE 12-1 Loxosceles reclusa (brown recluse, ‘fiddleback’) spider showing the classic violin-shaped marking on the back (dorsal side) of the cephalothorax. Note the long slender legs and oval body segment with short hairs. The arrow is pointing toward the classic violin marking. (From Ford M, Delaney K, Ling L, et al. Clinical Toxicology. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2001.)

The incidence of L. reclusa bites predominantly occurs from April through October in the USA. The venom of the brown recluse spider contains at least 11 protein components. Most are enzymes with cytotoxic activity.16 Sphingomyelinase D is believed to be the enzyme responsible for dermonecrosis and activity on red blood cell membranes.17–19 In addition to the local effects, the venom has activity against neutrophils and the complement pathway that induces an immunologic response.19–21 The resulting effect is a necrotic dermal lesion and the possibility that a systemic response will be life threatening.

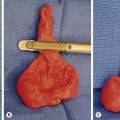

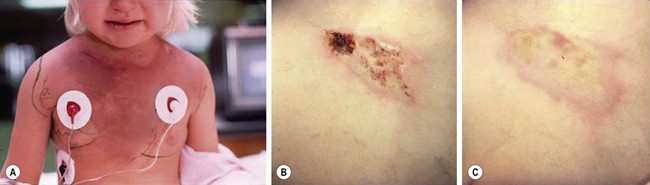

The prevalence of brown recluse spider envenomations is unknown. The victim may not feel the bite or may only feel a mild pinprick sensation. Many victims are bitten while they sleep and may be unaware of the envenomation until a wound develops. The majority of victims do not see the spider at the time of the bite.22 Typically, the bite progressively begins to itch, tingle, and become ecchymotic, indurated, and edematous within several hours.23 Often within hours, a characteristic bleb or bullae will form. The tissue under a blister is likely to become necrotic, but the extent of necrosis is not predictable. As the ischemia and inflammation progresses, the wound becomes painful and may blanch or become erythematous, forming a ‘target’ or ‘halo’ design. Inflammation, ischemia, and pain increase over the first few days after the bite as enzymes spread. Over hours to weeks, an eschar forms at the site of the bite. Eventually, this eschar sloughs, revealing an underlying ulcer that may require months to heal, usually by secondary intention (Fig. 12-2). On very rare occasions, the ulcer does not heal and may require surgical intervention.

FIGURE 12-2 (A) A 3-year-old girl hospitalized on the third day after a brown recluse spider bite for severe hemolytic anemia, hemoglobinuria, and ecchymosis (note the vast expansion of the ecchymosis secondary to hyaluronidase ‘spreading factor’ in the venom). There is no necrosis or ischemia, but a small bleb/blister is present over the right clavicle that, although not pathognomonic, is often present early in lesion progression. Also note that the cutaneous lesion is mild in comparison with this patient’s systemic presentation. (B) On the 15th day after envenomation, the lesion measures 5 cm × 2 cm. Multiple small areas of necrosis have become apparent in the past week. The largest area indicates the original bite size. The lesion’s edges have begun to involute with healing, and the ischemia is fading. (C) Nine months after the bite, the necrotic wound has healed with no significant scarring.

The need for hospitalization occurs if the patient develops systemic symptoms. Two studies documented that 14% to more than 50% of patients developed systemic symptoms, with fever being the most common symptom.10 Other common symptoms include a maculopapular rash, nausea and vomiting, headache, malaise, muscle/joint pain, hepatitis, pancreatitis, and other organ toxicity. Life-threatening systemic effects include hemolysis (intravascular and/or extravascular), coagulopathy, and multiple organ system failure. Secondary effects include sepsis, necrotizing fasciitis, and shock.24–26 Hemolysis usually manifests within the first 96 hours. However, late presentations can occur. When hemolysis does develop, it can take four to seven days (or longer) to resolve. Complications such as cardiac dysrhythmias, coma, respiratory compromise, pulmonary edema, congestive heart failure, renal failure, and seizures can occur.

The diagnosis of a brown recluse spider envenomation is largely one of exclusion as it is rare to see or identify the spider. While the wound can look classic for an envenomation, other etiologies must be considered (Box 12-2). Certain laboratory findings can be consistent with a brown recluse spider envenomation but are not specific in making the diagnosis (Box 12-3).

Controversy surrounds the treatment of dermal and systemic symptoms of loxoscelism. Medications such as dapsone, nitroglycerin, and tetracycline have been used. Also, hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) therapy has been advocated as has excision of the necrotic wound. However, none of these has proven to be effective in treating or preventing the ulcer development. In South America, an antivenom has been developed and used in the treatment of Loxosceles envenomations. Unfortunately, the usual long delay in seeking medical care often leads to ineffective use of this antivenom.27 An antivenom is not available in North America.

The use of dapsone, a leukocyte inhibitor, has been advocated in case reports and animal studies.28–30 However, other animal studies have shown no benefit from this treatment. In an animal study,31 piglets received venom and were randomized to receive one of four treatments: no treatment, HBO, dapsone, or dapsone with HBO. Neither dapsone, HBO, nor the combination treatment reduced necrosis compared with controls. A second study compared the use of HBO, dapsone, or cyproheptadine against no treatment in decreasing the necrotic wound after envenomation with L. deserta venom. No statistical difference was seen with respect to lesion size, ulcer size, or histopathologic ranking.32 In addition, the use of dapsone is not without risk, especially hypersensitivity reactions.33 Therapeutic doses of dapsone are associated with hemolytic anemia, methemoglobinemia, and other hematologic effects in patients with and without glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency.

Topically applied nitroglycerin as a vasodilator had been advocated but is not effective in preventing necrosis.34 Tetracycline has been shown to be effective. Rabbits were inoculated with Loxosceles venom and randomized to receive topical doxycycline, topical tetracycline, or placebo.35 Those who received topical tetracycline had reduced progression of the dermal lesion. However, treatment was started at six hours after envenomation, which may not be realistic after a human bite. In addition, the agents used for this research study are not commercially available in the United States. Further studies need to be performed before topical tetracycline can be recommended.

HBO has been advocated for treatment to prevent progression of the necrotic wound. The initial use of HBO was based on the belief that tissue hypoxia was partially responsible for the subsequent necrosis seen after a bite. As mentioned previously, no statistical differences were noted in animal studies that compared dapsone and HBO.31,32 Similar results have been seen in animal studies assessing the effect of HBO alone.36,37 However, a randomized, controlled trial of HBO in a rabbit model in which standard HBO was used showed a significantly reduced wound diameter at ten days.38 No significant change in blood flow at the wound center or 1–2 cm from the wound center was seen. HBO is expensive and not without complications. At the present time, much of the literature contradicts the benefit of HBO for brown recluse spider envenomations. As such, it is not currently recommended as a therapy for these bites, but may be helpful in patients with underlying/preexisting vascular compromise such as sickle cell anemia or diabetes.

Early surgical intervention is not helpful because the venom diffuses rapidly throughout the soft tissues surrounding the bite.39 In addition, patients may be more at risk for delayed wound healing and excessive scarring if operation occurs within the first 72 hours of the bite.40,41 Debridement of enlarging blebs is proposed with the theory that toxins exist within the blister fluid. However, necrosis almost always occurs beneath the blisters.42 The question is whether surgical intervention should be advocated late after envenomations? The wound from the brown recluse spider may take two to three months to heal. Thus, skin grafting of a non-healing necrotic area should be delayed up to 12 weeks to allow for neovascularization of the demarcated area.43

Treatment of systemic symptoms largely involves supportive care. Patients should be monitored closely for hemolysis (and children hospitalized) if systemic symptoms such as fever and rash develop. Systemic corticosteroids seem to suppress hemolysis and may be needed for five to ten days with a subsequent tapering dose.43 Methylprednisolone can be administered as a 1.0–2.0 mg/kg intravenous loading dose (no maximum) followed by a 0.5–1.0 mg/kg maintenance dose every six hours. Hydration to maintain good urine output is required to prevent acute renal tubular necrosis if hemolysis or hematuria occurs. Antibiotics are not generally required early in the care of these patients because the spider does not inoculate humans with bacteria. However, secondary infections can occur and lead to sepsis, toxic shock syndrome, and necrotizing fasciitis. These complications require close observation and antibiotic therapy to cover anaerobic, staphylococcal, and streptococcal infections.

Black Widow Spider

Black widow spiders (Latrodectus mactans) are found throughout North America.44 They can usually be found outdoors in warm, dark places, or in a garage or basement. They are web-making spiders and usually strike when their web is disturbed. The female spider is readily recognized as she is a black spider with a red marking on her abdomen in the shape of an hourglass. Widow spiders have a neurotoxic venom that is responsible for their clinical effects. The venom, α-latrotoxin, acts on the neuromuscular junction to cause depletion of acetylcholine at motor endings and catecholamines at the postganglionic sympathetic synaptic sites, which is followed by complete blockade of the neuromediator release.45

In the majority of cases, a pinprick sensation may be felt at the time of a bite. A ‘halo’ lesion may develop, but this tends to disappear within 12 hours of envenomation. A few hours after the bite, the regional lymph nodes and affected extremity may become tender. Depending on where the bite occurs, pain usually migrates to the large muscle groups in the thigh, buttock, abdomen or chest. The most common presenting complaint is intractable abdominal, chest, back, or leg pain, depending on the site of the bite.46 Board-like rigidity of the abdomen, shoulders, and back may develop that may lead to misdiagnosis of a surgical abdomen or other etiology. The pain generally peaks at two to three hours, but can last up to 72 hours.

Crotalid Snake Envenomations

In the USA, there are two major classes of poisonous snakes: crotalids and elapids. Crotalids, otherwise known as pit vipers, are indigenous to almost every state and account for the vast majority of poisonous snake bites in the USA annually. Most snake bites occur during the warm summer months when both snakes and humans are more active and thus more likely to come into contact with each other. It is thought that up to 20% of snake bites are ‘dry bites’ and do not result in envenomation.47

Crotalids can be classified into three major groups: rattlesnakes, cottonmouths (water moccasins), and copperheads. Copperheads are responsible for the majority of crotalid envenomations. In general, these bites are less severe and rarely result in systemic toxicity.48,49 Rattlesnake envenomations more commonly produce coagulopathy and systemic toxicity.

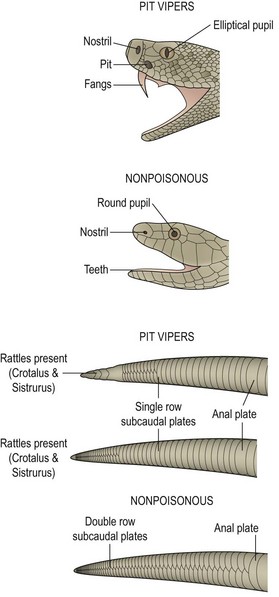

Crotalids have several physical features that help distinguish them from nonpoisonous snakes (Fig. 12-3). Crotalids have triangular heads and elliptical pupils. Nonpoisonous snakes have round heads and pupils. Crotalids have a single row of subcaudal plates/scales distal to the anal plate, whereas nonpoisonous snakes have a double row of subcaudal plates. Most importantly, crotalids have two retractable fangs and the characteristic heat-seeking pit located between the nostril and the eye. Nonpoisonous snakes have short, pointy teeth, but no fangs.

FIGURE 12-3 Identifying characteristics of pit vipers and nonpoisonous snakes. The presence or absence of a single row of subcaudal plates may be the only identifying feature in a decapitated snake. (From Ford M, Delaney K, Ling L, et al. Clinical Toxicology. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2001.)

Crotalid Venom Pharmacology/Pathophysiology

Crotalid venom is a complex mixture of proteins, including metalloproteinases, collagenase, hyaluronidase, and phospholipase.50 These enzymes act to destroy tissue at the site of envenomation. Damage to the vascular endothelium and basement membranes leads to edema, ecchymosis, and bullae formation. Concurrently with local tissue destruction, venom is absorbed systemically and can result in shock and coagulopathy. The potency of venom varies with the snake’s age, species, diet, and time of year.47 Even for the same snake, the composition and potency of venom can vary substantially based on these factors.

Clinical Effects

In questioning the patient, one should ascertain the circumstance and timing of the bite as well as any first aid methods that were used. Knowing what prehospital measures were instituted can be extremely helpful. Certain therapies such as incision, excision, and suction may result in significant local trauma and act to confound the assessment of local injury. The clinician should determine if the patient has previously received antivenom because sensitization can occur, thereby placing the patient at higher risk for an allergic reaction. Health care providers should be cautious regarding the reliability of the victim’s identification of the snake. It is often assumed that rattlesnakes will rattle their tails before biting. However, this is not always the case. Also, rattles may be absent from rattlesnakes due to shedding or trauma. Victims occasionally trap or kill the snake and bring it to the emergency department. Vigilance is necessary when examining these snakes because they are capable of biting again. Even dead snakes have been known to bite reflexively for up to an hour after they have been killed.47

Envenomations can result in significant local pain and swelling. The patient typically has two fang marks at the location of the bite. Often, there is mild bleeding or oozing from the wound. Swelling typically develops within one to two hours, and ecchymosis or bullae (some hemorrhagic) may appear. Several different grading systems have been developed to grade the severity of snake bites.47,51 The minimal, moderate, severe model is a simple tool that can help assess severity and determine the need for antivenom (Table 12-3).

TABLE 12-3

Clinical Grading of Snake Envenomations

| Grading | Comments |

| Minimal | Mild local swelling without progression; no systemic or hematologic toxicity |

| Moderate | Local swelling with proximal progression and/or mildly abnormal laboratory parameters (e.g., decreased platelets, prolonged coagulation studies) |

| Severe | Marked swelling with progression and/or significant systemic toxicity (shock, compartment syndrome) or laboratory abnormalities (severe thrombocytopenia/coagulopathy) |

Adapted from Gold BS, Dart RC, Barish RA. Bite of Venomous Snakes. N Engl J Med 2002;347:347–56.

Serial measurements of the extremity are required to detect progression of the swelling. The local effects have traditionally been documented by drawing a line demarcating the progression of the swelling. Unfortunately, this method requires subjective interpretation and can result in measurement variability. Measurement of the limb circumference is more objective and can be easily repeated to determine any progression (Fig. 12-4). These measurements should be recorded every 15 minutes for the first two hours and then less frequently (every 30-60 minutes). In addition to measuring the limb circumference, serial neurovascular examinations can identify ischemia or evidence of compartment syndrome.

FIGURE 12-4 A 15-year-old boy was bitten on his right hand by a timber rattlesnake. Note the significant swelling of the arm. Serial limb circumference measurements were documented; the lines mark the progression of the swelling. The patient did well after treatment with Fab antivenom.

Compartment syndrome is rare (<1–2%) after snake envenomation because it is unusual for a snake’s fangs to penetrate the muscle fascia.52 The true incidence is difficult to ascertain from the literature because many of the older case series report the use of prophylactic fasciotomies without measuring the compartment pressure.52–54 Although swelling may be severe, it is almost always localized to the subcutaneous tissue. If there is concern for compartment syndrome in the setting of severe pain and swelling, measurement of compartment pressures is needed. Even if elevated compartment pressures are found, treatment with antivenom is usually sufficient to reduce the elevated pressures and reverse the compartment syndrome.52–56 Given the efficacy and safety of the current crotalid antivenom, prophylactic fasciotomies are not routinely indicated in the setting of an envenomation.57 Recent evidence has shown that prophylactic fasciotomies worsen local effects and do not improve clinical outcomes.58,59 If compartment pressures are elevated, they should be re-measured after antivenom administration and repeat antivenom should be given, if needed. If the pressures remain elevated for more than 4 hours despite antivenom, then fasciotomy is indicated (Fig. 12-5). Measurement of finger compartment pressures is not possible. If significant concern exists about the viability of the finger, a digit dermotomy is indicated.59

FIGURE 12-5 The need for fasciotomy for compartment syndrome may be suggested by excessive swelling in the soft tissue, but compartment pressures are rarely elevated significantly. Prophylactic fasciotomy is based on the belief that it protects against compartment syndrome. Such practices are unnecessary and can be catastrophic in venom-defibrinated patients. (From Brent J, Wallace K, Burkhart K, et al. Critical Care Toxicology: Diagnosis and Management of the Critically Poisoned Patient. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005.)

Systemic manifestations present in a variable fashion after envenomation. Nonspecific symptoms and signs include nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, and metallic taste. Hypotension and shock can develop in severe cases. Severe rattlesnake envenomations often cause coagulopathy with a disseminated intravascular coagulation-like syndrome. Thrombocytopenia has been noted to be severe and prolonged after timber rattlesnake envenomations.60 Canebrake rattlesnake envenomations have been associated with significant rhabdomyolysis.61 Rarely, following envenomation, patients have been noted to have extremely rapid decompensation. In these cases, it is thought that the patient experiences either an immediate anaphylactoid-like reaction or receives a significant intravascular venom load.62

Management

Historically, different procedures and therapies have been advocated in the prehospital and in-hospital management of snake bites. Treatments such as cryotherapy and electric shock are associated with significant complications and are not recommended.63 It is commonly thought that tourniquets should be applied to the affected extremity. However, their use has not been found to improve outcomes and evidence suggests they may worsen local toxicity.64–66 Therefore, their use should be discouraged. Given the short transport times of most patients, the morbidity associated with tourniquet application (limb ischemia) outweighs any potential benefit. In those situations in which the victim is in a remote location that is hours away from an emergency department, the use of a constriction band should be considered. There are limited data to suggest that constriction bands decrease the rate of systemic venom absorption.64 Constriction bands differ from venous tourniquets in that they serve to impede lymphatic return rather than blood flow. When placed correctly, two fingers should easily slip under a constriction band.

Pressure immobilization is another modality commonly recommended for snake bites. It involves wrapping the entire limb in an elastic compression bandage and then immobilizing the limb in extension with a splint. Although likely effective in cases of elapid envenomations,67 their use in cases of crotalid envenomation should be discouraged despite a recent position statement supporting their use.68 Animal models of crotalid envenomation demonstrated pressure immobilization slightly prolonged the time to death but was associated with a significant increase in extremity compartment pressures.69,70 Additionally, it has been shown that pressure immobilization bandages are often applied incorrectly and can act as a tourniquet.71

Suction using a commercially available extractor device has been previously suggested. The concept is that the suction would pull the venom out of the wound if applied shortly after the bite. However, it has been demonstrated that these devices are not efficacious and remove less than 1% of injected venom.72 Also, these devices may actually increase the amount of local tissue destruction.73 Therefore, use of extractor devices in the prehospital or hospital setting is not recommended.

Incision therapy, often combined with suction, gained favor in the early 20th century. This procedure entailed making several parallel incisions longitudinally along the affected extremity. While early animal models demonstrated some survival improvement, subsequent human studies have failed to show any change in clinical outcomes.74 Incising the wound also risks injury to underlying tendons, nerves, and blood vessels, and increases infection rates.74–76

In-hospital management should initially focus on assessing and supporting the airway, breathing, and circulation. Anaphylactic reactions have been reported after envenomation.77 The initial evaluation should assess the patient for shock and hypoperfusion. Hypotension mandates aggressive resuscitation with crystalloid, antivenom (see later), and possibly vasopressors. If the patient arrives in the emergency department with a tourniquet on the extremity, it should be slowly loosened and removed over 20 to 30 minutes. Rapid removal of the tourniquet could result in a bolus of the venom into the central circulation, resulting in decompensation of the patient.64 Intravenous access should be obtained in the noninjured extremity, with placement of a second access line in those with significant envenomation. Opioids are often required for management of pain. The patient’s tetanus should be updated as needed. Prophylactic antibiotics are not warranted because the risk of infection resulting from snake bites is less than 5%.78 Although snakes carry pathogenic bacteria in their mouths, the majority of infections are secondary to the victim’s normal skin flora.

Antivenom is indicated for envenomations displaying more than minimal local effects (Box 12-4). The older Wyeth (Collegeville, PA) polyvalent antivenom that was introduced in the USA in 1954 is no longer manufactured. This product was a crudely purified, equine-derived IgG antibody directed against the venom of several crotalids. As it contained foreign proteins and was highly immunogenic, the incidence of immediate hypersensitivity reactions was high. Approximately 50% of recipients developed urticaria or signs of anaphylactic shock.79 Serum sickness, a delayed immunologic reaction to the foreign proteins, was much more commonly associated with this antivenom (approximately 50% of cases treated with more than five vials of the Wyeth antivenom).79 It typically occurs one to three weeks after antivenom administration and manifests clinically as a fever, rash, arthralgias, myalgias, and occasionally glomerulonephritis and pericarditis. It is generally self-limited and can be treated with corticosteroids and antihistamines.

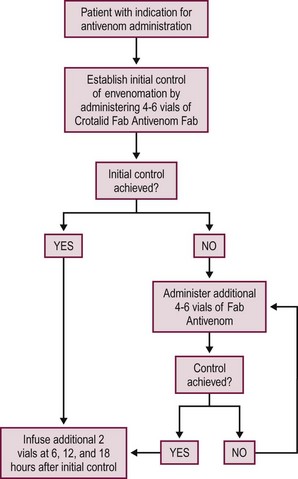

Fortunately, a new polyvalent immune Fab antivenom (CroFab, Protherics, Inc., Brentwood, TN) is available that is much safer and associated with significantly fewer adverse reactions. It is a highly purified product that contains the Fab fragments of IgG antibodies. The product is sheep-derived and is effective against all North American crotalid species. The incidence of immediate hypersensitivity reactions is less than 5% to 10%.80–84 Many of the hypersensitivity reactions are mild (urticaria) and do not prevent further antivenom administration. Anaphylaxis is uncommon. Likewise, the incidence of serum sickness is also less than 5%.83,84 The dosing of polyvalent immune Fab is based on the clinical severity and response of the patient to the antivenom (Fig. 12-6). The dosing is not weight based. Therefore, the dosing in children is the same as in adults. Skin testing is not required. Clinical trials have demonstrated improved outcomes when regular follow-up doses of antivenom were given for recurrence (see later) of local and systemic toxicity in those who received a single dose of antivenom. This resulted in the development of the currently recommended dosing schedule. Multiple studies have demonstrated that the polyvalent immune Fab antivenom is efficacious in ameliorating the local and systemic venom toxicity. Recent analysis of pediatric data also demonstrates excellent efficacy and safety in treating children as young as 18 months of age. There were no cases of anaphylaxis in pediatric patients (>100 cases) reported in five case series.85–89 Liberal use should be considered for bites involving the hands or feet because these envenomations are associated with significant morbidity and prolonged recovery.90

FIGURE 12-6 This schematic depicts management of the patient who needs crotalid polyvalent immune Fab antivenom.

Recurrence is defined as worsening of local and/or systemic toxicity after a period of improvement with antivenom therapy. This results from the pharmacokinetic differences between the antivenom and venom.91 The Fab components have a low molecular weight and are small enough to be freely filtered by the kidney. This results in an elimination half-life of Fab antivenom of about 15 to 20 hours versus venom that has a half-life of approximately 40 hours.91,92 Multiple reports have documented progression of swelling or worsening hematologic toxicity after antivenom therapy.80,83,93 Those patients who develop hematologic toxicity during initial treatment are at highest risk for recurrence. Administration of antivenom is usually effective in treating further local progression. Although hematologic toxicity does not typically result in clinically significant bleeding, further antivenom administration is not effective in completely normalizing hematologic abnormalities.83,94 Close monitoring is indicated, and treatment can be resumed in those with bleeding or markedly abnormal laboratory parameters.94

The disposition of patients who are bitten is dependent on the severity of the envenomation. Discharge after eight to 12 hours of observation can be considered in those circumstances in which it is thought that no significant envenomation occurred (dry bite).95 There should be no appreciable local swelling, and results of initial laboratory studies and repeat laboratory studies before discharge should be normal. Patients with local swelling or evidence of systemic toxicity should be admitted for further evaluation and management. Rattlesnake bite victims from those areas in which the Mojave rattlesnake is endemic should be monitored for neurotoxicity.

Coral Snake Envenomation

The coral snake is the only poisonous elapid snake native to the USA. While there are several species of coral snakes in the USA, the species of greatest concern is found in Florida and southern Georgia. These snakes are brightly colored and have bands in a distinctive pattern (black, yellow, red). This order gives rise to the common phrases, ‘red on yellow, kill a fellow’ and ‘red on black, venom lack,’ that can help to differentiate a coral snake from the nonpoisonous king snake. Unlike crotalids, coral snakes have round heads and pupils. Instead of fangs, they have short teeth. Up to 25% of bites result in no significant envenomation.96

Unlike crotalids that produce local tissue destruction and coagulopathy, venom from elapids is associated with neurotoxicity. After a bite, local effects tend to be mild. Of greater concern is the risk of progressive weakness and resulting respiratory failure. Neurologic symptoms (cranial nerve palsies, weakness) typically develop within two hours but may be delayed up to 13 hours.96 Given the lack of significant local effects, surgical management is not indicated.

Coral snake antivenom is an equine-derived IgG. In the largest series describing USA coral snake envenomations, immediate hypersensitivity reactions occurred in 15% of patients, whereas serum sickness was reported in 10%.96

References

1. Bronstein, AC, Spyker, DA, Cantilena, LR, et al. 2010 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS). Clin Toxicol. 2011; 49:910–1011.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary of Notifiable Diseases—United States, 2009. MMWR. 2011; 58:33.

3. Wu, DT. Tetanus. In: Wolfson AB, Hendey GW, Hendry PL, et al, eds. Harwood-Nuss’ Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:718–720.

4. Loscalzo, LI, Ryan, J, Loscalzo, J, et al. Tetanus: A clinical diagnosis. Am J Emerg Med. 1995; 13:488–490.

5. American Academy of Pediatrics. Tetanus (lockjaw), Bite Wounds. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, et al, eds. Redbook: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:187–191.

6. Capellan, O, Hollander, JE. Management of lacerations in the emergency department. In: Peth HA, editor. High Risk Presentations. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2003; 21:205–231.

7. Talan, DA, Citron, DM, Abrahamian, EM, et al. Bacteriologic analysis of infected dog and cat bites. N Engl J Med. 1999; 340:85–92.

8. Talan, DA, Abrahamian, EM, Moran, GJ, et al. Clinical presentation and bacteriologic analysis of infected human bites in patients presenting to emergency departments. Clin Infect Dis. 2003; 37:1481–1489.

9. Pretty, IA, Anderson, GS, Sweet, DJ. Human bites and risk of human immunodeficiency virus transmission. Am J Forens Med Pathol. 1999; 20:232–239.

10. Human rabies prevention. United States, 1999. Recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Morb Mortal wkly Rep. 1999; 48(No. RR-1):1–21.

11. World Health Organization. WHO expert committee on rabies. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2005; 931:1–121.

12. Rabies Prevention Policy Update. New Reduced-Dose Schedule. Committee on Infectious Diseases. Pediatrics. 2001; 127:785–787.

13. Coddington, JA, Levi, HW. Systematics and evolution of spiders (Araneae). Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1991; 22:565–592.

14. Sams, HH, Dunnick, CA, Smith, ML, et al. Necrotic arachnidism. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001; 44:561–573.

15. Vetter, RS. Spiders of the genus Loxosceles (Araneae, Sicariidae): A review of biological, medical, and psychological aspects regarding envenomations. J Arachnol. 2008; 36:150–163.

16. Forrester, LJ, Barrett, JT, Campbell, BJ. Red blood cell lysis induced by the venom of the brown recluse spider: The role of sphingomyelinase D. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1978; 187:355–365.

17. Rees, RS, Nanney, LB, Yates, RA, et al. Interaction of brown recluse spider venom on cell membranes: The inciting mechanism? J Invest Dermatol. 1984; 83:270–275.

18. Tambourgi, DV, Magnoli, FC, van den Berg, CW, et al. Sphingomyelinases in the venom of the spider Loxosceles intermedia are responsible for both dermonecrosis and complement-dependent hemolysis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998; 251:366–373.

19. Majeski, JA, Stinnett, JD, Alexander, JW, et al. Action of venom from the brown recluse spider (Lososceles reclusa) on human neutrophils. Toxicon. 1977; 15:423–427.

20. Futrell, JM, Morgan, PN. Inhibition of human complement components by Loxosceles reclusa venom. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1978; 57:275–278.

21. Kurpiewski, G, Campbell, JF, Forrester, LJ, et al. Alternate complement pathway activation by recluse spider venom. Int J Tissue React. 1981; 3:39–45.

22. Wright, SW, Wrenn, KD, Murray, L, et al. Clinical presentation and outcome of brown recluse spider bite. Ann Emerg Med. 1997; 30:28–32.

23. Wasserman, GS. Brown recluse and other necrotizing spiders. In: Ford MD, Delaney KA, Ling LJ, et al, eds. Clinical Toxicology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2001:878–884.

24. Williams, ST, Khare, VK, Johnston, GA, et al. Severe intravascular hemolysis associated with brown recluse spider envenomation. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995; 104:463–467.

25. Berger, RS, Adelstein, EH, Anderson, PC. Intravascular coagulation: The cause of necrotic arachnidism. J Invest Dermatol. 1973; 61:142–150.

26. de Souza, AL, Malague, CM, Sztajnbok, J, et al. Loxosceles venom–induced cytokine activation, hemolysis and acute kidney injury. Toxicon. 2008; 51:151–156.

27. Pauli, I, Puka, J, Gubert, IC, et al. The efficacy of antivenom in loxoscelism treatment. Toxicon. 2006; 48:123–137.

28. King, LE, Rees, RS. Dapsone treatment of a brown recluse bite. JAMA. 1983; 250:648.

29. Wesley, RE, Close, LW, Ballinger, WH, et al. Dapsone in the treatment of presumed brown recluse spider bite of the eyelid. Ophthalmic Surg. 1985; 16:116–117.

30. Barrett, SM, Romine-Jenkins, M, Fisher, DE. Dapsone or electric shock therapy of brown recluse spider envenomation? Ann Emerg Med. 1994; 24:21–25.

31. Hobbs, GD, Anderson, AR, Greene, TJ, et al. Comparison of hyperbaric oxygen and dapsone therapy for Loxosceles envenomation. Acad Emerg Med. 1996; 3:758–761.

32. Phillips, S, Kohn, M, Baker, D, et al. Therapy of brown spider envenomation: A controlled trial of hyperbaric oxygen, dapsone and cyproheptadine. Ann Emerg Med. 1995; 25:363–368.

33. Wille, RC, Morrow, JD. Case report: Dapsone hypersensitivity syndrome associated with treatment of the bite of a brown recluse spider. Am J Med Sci. 1988; 296:270–271.

34. Lowry, BP, Bradfield, JF, Carroll, RG, et al. A controlled trial of topical nitroglycerin in a New Zealand white rabbit model of brown recluse spider envenomation. Ann Emerg Med. 2001; 37:161–165.

35. Paixao-Cavalcante, D, van den Berg, CW, Goncalves-de-Andrade, RM, et al. Tetracycline protects against dermanecrosis induced by. Loxosceles spider venom. J Invest Dermatol. 2007; 127:1410–1418.

36. Strain, GM, Snider, TG, Tedford, BL, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen effect on brown recluse spider (Loxosceles reclusa) envenomation in rabbits. Toxicon. 1991; 29:988–996.

37. Merchant, ML, Hinton, JF, Geren, CR. Effect of hyperbaric oxygen on sphingomyelinase D activity of brown recluse spider (Loxosceles reclusa) venom as studied by 31P nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997; 56:335–338.

38. Maynor, ML, Moon, RE, Klitzman, B, et al. Brown recluse spider envenomation: A prospective trial of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Acad Emerg Med. 1997; 4:184–192.

39. Gomez, HF, Greenfield, DM, Miller, MJ, et al. Direct correlation between diffusion of Loxosceles reclusa venom and extent of dermal inflammation. Acad Emerg Med. 2001; 8:309–314.

40. Rees, R, Shack, B, Withers, E, et al. Management of the brown recluse spider bite. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1981; 68:768–773.

41. Rees, R, Altenbern, DP, Lynch, JB, et al. Brown recluse spider bites: A comparison of early surgical excision versus dapsone and delayed surgical excision. Ann Surg. 1985; 202:659–663.

42. Wasserman, GS, Lowry, JA. Loxosceles spiders. In: Brent J, Wallace KL, Burkhart KK, et al, eds. Critical Care Toxicology: Diagnosis and Management of the Critically Poisoned Patient. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby; 2005:1195–1203.

43. Wasserman, GS, Anderson, PC. Loxoscelism and necrotic arachnidism. Clin Toxicol. 1983-1984; 21:451–472.

44. Bond, GR. Snake, spider, and scorpion envenomation in North America. Pediatr Rev. 1999; 20:147–151.

45. Kunkel, DB. The sting of the arthropod. Emerg Med. 1996; 28:136–141.

46. Clark, RF, Wethern-Kestner, S, Vance, MV, et al. Clinical presentation and treatment of black widow spider envenomation: A review of 163 cases. Ann Emerg Med. 1992; 21:782–787.

47. Russell, FE. Snake Venom Poisoning. Great Neck, NY: Scholium International; 1983.

48. Scharman, EJ, Noffsinger, NJ. Copperhead snakebites: Clinical severity of local effects. Ann Emerg Med. 2001; 38:55–61.

49. Thorson, A, Lavonas, EJ, Rouse, AM, et al. Copperhead envenomations in the Carolinas. J Tox Clin Toxicol. 2003; 41:29–35.

50. Gold, BS, Dart, RC, Barish, RA. Bite of venomous snakes. N Engl J Med. 2002; 347:347–356.

51. Dart, RC, Hurlbut, KM, Garcia, R, et al. Validation of a severity score for the assessment of Crotalid snakebite. Ann Emerg Med. 1996; 27:321–326.

52. Cumpston, KL. Is there a role for fasciotomy in crotaline envenomations in North America. Clin Toxicol. 2011; 49:351–365.

53. Shaw, BA, Hosalkar, HS. Rattlesnake bites in children: Antivenin treatment and surgical indications. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002; 84:1624–1629.

54. Corneille, MG, Larson, S, Stewart, RM, et al. A large single center experience with treatment of patients with Crotalid envenomations: Outcomes with and evolution of antivenin therapy. Am J Surg. 2006; 192:848–852.

55. Tanen, DA, Danish, DC, Clark, RF. Crotalid polyvalent immune Fab antivenom limits the decrease in perfusion pressure of the anterior leg compartment in a porcine crotaline envenomation model. Ann Emerg Med. 2003; 41:384–390.

56. Gold, BS, Barish, RA, Dart, RC, et al. Resolution of compartment syndrome after rattlesnake envenomation utilizing noninvasive measures. J Emerg Med. 2003; 24:285–288.

57. Tanen, DA, Danish, DC, Grice, GA. Fasciotomy worsens the amount of myonecrosis in a porcine model of crotaline envenomation. Ann Emerg Med. 2004; 44:99–104.

58. Stewart, RM, Page, CP, Schwesinger, WH, et al. Antivenin and fasciotomy/debridement in the treatment of severe rattlesnake bite. Am J Surg. 1989; 158:543–547.

59. Hall, EL. Role of surgical intervention in the management of crotaline snake envenomation. Ann Emerg Med. 2001; 37:175–180.

60. Bond, GR, Burkhart, KK. Thrombocytopenia following timber rattlesnake envenomation. Ann Emerg Med. 1997; 30:40–44.

61. Carroll, RR, Hall, EL, Kitchens, CS. Canebrake rattlesnake envenomation. Ann Emerg Med. 1997; 30:45–48.

62. Curry, SC, O’Connor, AD, Ruha, AM. Rapid-onset shock and/or anaphylactoid reactions from rattlesnake bites in central Arizona [abstract]. J Med Toxicol. 2010; 6:241.

63. McKinney, PE. Out-of-hospital and interhospital management of crotaline snakebite. Ann Emerg Med. 2001; 37:168–174.

64. Burgess, JL, Dart, RC, Egen, NB, et al. Effects of constriction bands on rattlesnake venom absorption: A pharmacokinetic study. Ann Emerg Med. 1992; 21:1086–1093.

65. Sutherland, SK, Coulter, AR. Early management of bites by eastern diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus) studies in monkeys (Macaca fascicularis). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1981; 30:497–500.

66. Straight, RC, Glenn, JL. Effects of pressure/immobilization on the systemic and local action of venoms in a mouse tail model [abstract]. Toxicon. 1985; 23:40.

67. German, BT, Hack, JB, Brewer, K, et al. Pressure-immobilization bandages delay toxicity in a porcine model of eastern coral snake (Micrurus fulvius fulvius) envenomation. Ann Emerg Med. 2005; 45:603–608.

68. Markenson, D, Ferguson, JD, Chameides, L, et al. Part 17: First Aid: 2010 American Heart Association and American Red Cross Guidelines for First Aid. Circulation. 2010; 122(18 Suppl 3):S934–S946.

69. Bush, SP, Green, SM, Laack, TA, et al. Pressure immobilization delays mortality and increases intracompartmental pressure after artificial intramuscular rattlesnake envenomation in a porcine model. Ann Emerg Med. 2004; 44:599–604.

70. Meggs, WJ, Courtney, C, O’Rourke, D, et al. Pilot studies of pressure-immobilization bandages for rattlesnake envenomations. Clin Toxicol. 2010; 48:61–63.

71. American College of Medical Toxicology, American Academy of Clinical Toxicology, American Association of Poison Control Centers, European Association of Poison Control Centers and Clinical Toxicologists, International Society on Toxinology, Asia Pacific Association of Medical Toxicology. Pressure immobilization after North American Crotalinae snake envenomation. Clin Toxicol. 2011; 49:881–882.

72. Alberts, MB, Shalit, M, LoGolbo, F. Suction for venomous snakebite: A study of ‘mock venom’ extraction in a human model. Ann Emerg Med. 2004; 43:181–186.

73. Bush, SP, Hegewald, KG, Green, SM, et al. Effects of a negative pressure venom extraction device (extractor) on local tissue injury after artificial rattlesnake envenomation in a porcine model. Wilderness Environ Med. 2000; 11:180–188.

74. Wingert, WA, Chan, L. Rattlesnake bites in southern California and rationale for recommended treatment. West J Med. 1988; 148:37–44.

75. Tokish, JT, Benjamin, J, Walter, F. Crotalid envenomation: The southern Arizona experience. J Orthop Trauma. 2001; 15:5–9.

76. Arnold, RE. Results of treatment of Crotalus envenomation. Am Surg. 1975; 41:643–647.

77. Brooks, DE, Graeme, KA, Ruha, AM, et al. Respiratory compromise in patients with rattlesnake envenomation. J Emerg Med. 2002; 23:329–332.

78. LoVecchio, F, Klemens, J, Welch, S, et al. Antibiotics after rattlesnake envenomation. J Emerg Med. 2002; 23:327–328.

79. Dart, RC, McNally, J. Efficacy, safety, and use of snake antivenoms in the United States. Ann Emerg Med. 2001; 37:181–188.

80. Dart, RC, Seifert, SA, Boyer, LV, et al. A randomized multicenter trial of Crotalidae Polyvalent Immune Fab (ovine) antivenom for the treatment of crotaline snakebite in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2001; 161:2030–2036.

81. Lavonas, EJ, Gerardo, CJ, O’Malley, G, et al. Initial experience with Crotalidae Polyvalent Immune Fab (ovine) antivenom in the treatment of copperhead snakebite. Ann Emerg Med. 2004; 43:200–206.

82. Dart, RC, Seifert, SA, Carroll, L, et al. Affinity-purified, mixed monospecific crotalid antivenom ovine Fab for the treatment of crotalid venom poisoning. Ann Emerg Med. 1997; 30:33–39.

83. Ruha, AM, Curry, SC, Beuhler, M, et al. Initial postmarketing experience with Crotalidae Polyvalent Immune Fab for the treatment of rattlesnake envenomation. Ann Emerg Med. 2002; 39:609–615.

84. Cannon, R, Ruha, AM, Kashani, J. Acute hypersensitivity reactions associated with administration of Crotalidae Polyvalent Immune Fab antivenom. Ann Emerg Med. 2008; 51:407–411.

85. Pizon, AF, Riley, BD, LoVecchio, F, et al. Safety and efficacy of Crotalidae Polyvalent Immune Fab in pediatric crotaline envenomations. Acad Emerg Med. 2007; 14:373–376.

86. Offerman, SR, Bush, SP, Moynihan, JA, et al. Crotaline Fab antivenom for the treatment of children with rattlesnake envenomation. Pediatrics. 2002; 110:968–971.

87. Rowden, AK, Holstege, CP, Kirk, MA. Pediatric copperhead envenomations [abstract]. Clin Toxicol. 2007; 45:644.

88. Rowden, AK, Boylan, VV, Wiley, SH, et al. Crofab use for copperhead envenomation in the young [abstract]. Clin Toxicol. 2006; 44:696–697.

89. Feng, S, Stephan, M. What a bite—Review of snakebites in children [abstract]. Clin Toxicol. 2005; 43:712.

90. Spiller, HA, Bosse, GM. Prospective study of morbidity associated with snakebite envenomation. J Tox Clin Toxicol. 2003; 41:125–130.

91. Seifert, SA, Boyer, LV. Recurrence phenomena after immunoglobulin therapy for snake envenomations: I. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of immunoglobulin antivenoms and related antibodies. Ann Emerg Med. 2001; 37:189–195.

92. Seifert, SA, Boyer, LV, Dart, RC, et al. Relationship of venom effects to venom antigen and antivenom serum concentrations in a patient with Crotalus atrox envenomation treated with a Fab antivenom. Ann Emerg Med. 1997; 30:49–53.

93. Bogdan, GM, Dart, RC, Falbo, SC, et al. Recurrent coagulopathy after antivenom treatment of Crotalid snakebite. South Med J. 2000; 93:562–566.

94. Boyer, LV, Seifert, SA, Cain, JS. Recurrence phenomena after immunoglobulin therapy for snake envenomations: II. Guidelines for clinical management with Crotaline Fab antivenom. Ann Emerg Med. 2001; 37:196–201.

95. Lavonas, EJ, Ruha, AM, Banner, W, et al. Unified treatment algorithm for the management of crotaline snakebite in the United States: Results of an evidence-informed consensus workshop. BMC Emerg Med. 2011; 11:2.

96. Kitchens, CS, Van Mierop, LHS. Envenomation by the eastern coral snake (Micrurus fulvius fulvius). JAMA. 1987; 258:1615–1618.