Chapter 33 Bipolar disorder with psychotic symptoms

EPIDEMIOLOGY, AETIOLOGY AND CLASSIFICATION

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a heritable mental illness. Approximately 1% of US adults experience persisting mood swings and fulfill criteria for a DSM-IV diagnosis of BD.1 First-degree relatives of bipolar individuals are significantly more likely to develop the disorder than the population at large. Bipolar illness in one identical twin corresponds to a 70% risk that the other twin will also have the disorder and the concordance risk is estimated at 15% in non-identical twins.2 Recent findings from genetic studies suggest that decreased expression of RNA coding for mitochondrial proteins results in dysregulations of energy metabolism in the brain, and especially in the hippocampus.3 Dysregulations in hypothalamic circuits involved in maintaining normal circadian rhythms probably cause the affective and behavioural symptoms described in Western psychiatric nosology as bipolar disorder I and bipolar disorder II. It has been suggested that both phases of BD may be manifestations of chronic folate deficiency;4 however, the aetiology of BD is varied and complex. Acutely manic patients frequently have abnormal EEG activity which may predict responsiveness to conventional pharmacological treatments.5

According to conventional Western psychiatric nosology, mania is a complex symptom pattern that may encompass disparate affective, behavioural and cognitive symptoms, including pressured speech, racing thoughts, euphoric or irritable mood, agitation, inflated self-esteem, distractibility, excessive or inappropriate involvement in pleasurable activities, increased goal-directed activity, diminished need for sleep and, in severe cases, psychosis.6 According to the DSM-IV-TR,6 a manic episode is diagnosed when elevated or irritable mood persists for at least 1 week, is accompanied by at least three of the above symptoms, is associated with severe social or occupational impairment, and cannot be adequately explained by a pre-existing medical or psychiatric disorder or the effects of substance abuse. In contrast to frank mania, the diagnosis of a hypomanic episode requires sustained irritable or euphoric mood lasting at least 4 days but does not cause severe impairment in social or occupational functioning; three or more of the above symptoms; and exclusion of medical or psychiatric disorders that may manifest as these symptoms. According to the DSM-IV, bipolar I is diagnosed when an individual has experienced one or more manic episodes, while one or more hypomanic episodes are required for a diagnosis of bipolar II disorder. Bipolar I disorder can be diagnosed after only one manic episode; however, the typical bipolar I patient has had several manic episodes, and at least 80% of patients who experience mania will have recurring manic episodes.7 According to the DSM-IV, a history of depressive episodes is not required for a formal diagnosis of bipolar I disorder. In contrast, bipolar II disorder can be diagnosed only in cases when at least one hypomanic episode and at least one depressive episode have been documented. In both disorders moderate or severe depressive episodes typically alternate with manic symptoms; however, in ‘mixed mania’ symptoms of mania and depressed mood overlap. Another variant called rapid cycling is diagnosed when at least four complete cycles of depressed mood and mania occur during any 12-month period. A mild variant of bipolar disorder is called cyclothymic disorder. Cyclothymic disorder is diagnosed when several hypomanic and depressive episodes take place over a 2-year period in the absence of severe manic, mixed or depressive episodes. It is estimated that individuals diagnosed with bipolar I disorder are symptomatic approximately 50% of the time. Bipolar patients experience depressive symptoms three times more often than mania, and five times more often than rapid cycling or mixed episodes.8

Distinguishing between transient episodes of mania and acute agitation caused by a medical or psychiatric disorder can pose diagnostic challenges. A careful history is needed to establish a persisting pattern of mood changes fluctuating between depression and mania or hypomania. Conventional laboratory tests and functional brain imaging studies are used to rule out the presence of medical disorders that can mimic symptoms of depressed mood or mania including, for example, thyroid disease, strokes (especially in the right frontal area of the brain), multiple sclerosis, (rarely) seizure disorders, and other neurological disorders. Irritability or euphoria alternating with periods of depressed mood is also associated with chronic abuse of stimulants, marijuana or other drugs. It is often difficult to establish a primary diagnosis of bipolar disorder after ruling out pre-existing psychiatric or medical disorders because of the variety of symptoms that can take place during a manic episode. For example, symptoms of irritability, agitation and emotional lability are frequent concomitants of chronic drug or alcohol abuse, psychotic disorders and personality disorders. Ongoing debate over the construct validity of BD will probably result in new diagnostic criteria in the next edition of the DSM, which is scheduled for completion in 2012.9 For example, it has been suggested that the ‘rapid cycling’ variant of bipolar disorder may more accurately correspond to a severe personality disorder than BD or other mood disorders.

RISK FACTORS

Several risk factors contribute to the rate of relapse and response to treatment in patients diagnosed with BD. A diagnosis of BD is one of the largest risk factors for suicide.10 Fewer than half of patients who take conventional maintenance treatments following an initial manic episode report sustained control of their symptoms.11 Furthermore, as many as 40% of bipolar patients who adhere to pharmacological treatment experience recurring manic or depressive mood swings while taking medications at recommended doses.11 As many as one-quarter of bipolar I patients attempt suicide, and many eventually succeed. Treatment of bipolar disorder should be maintained on a consistent, long-term basis to reduce the rate of re-hospitalisation and increase chances of full remission.12 Failure to initiate effective treatment that is well tolerated in the early stages of illness significantly increases the risk of relapse with associated increased risk of suicide.13 In patients with diagnosed BD, stressors, seasonal change, reduced sleep and stimulants or recreational drug use may provoke an episode of hypomania or mania (although sometimes the trigger may not appear to have a cause).14 Regular exercise, good nutrition, a strong social support network and a predictable, low-stress environment help reduce relapse risk.15,16

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT

Medication management

The American Psychiatric Association endorses the use of different conventional pharmacological agents, including mood stabilisers (e.g. lithium carbonate and valproate), antidepressants, antipsychotics and sedative-hypnotics, to treat BD.17 Antipsychotics are used to treat agitation and psychosis, which occur frequently in acute mania. Sedative hypnotics are prescribed for the severe insomnia that accompanies mania as well as for daytime management of agitation and anxiety.18 A significant percentage of bipolar patients must rely on conventional antidepressants to control depressive mood swings. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is an emerging treatment of both the acute manic phase and the depressive phase of bipolar disorder and does not risk mania induction; however, findings of controlled trials to date are highly inconsistent.19 Mania associated with psychosis is approached differently to a mixed episode that includes both manic and depressive symptoms. Conventional antipsychotics are appropriate first-line treatments of the auditory hallucinations that occur during an acute manic episode, while mixed episodes are often managed using a combination of two mood stabilisers or a mood stabiliser and antipsychotic.14

Psychotherapy and psychosocial interventions

Psychotherapy and psychosocial interventions in stable bipolar patients may potentially reduce relapse risk by providing psychological support, enhancing medication adherence, and helping patients address warning signs of recurring depressive or manic episodes before more serious symptoms emerge.20 A review of randomised studies on adjunctive psychotherapy and psychosocial interventions in bipolar patients concluded that adjunctive psychotherapy reduces symptom severity and improves functioning.20 Family therapy and interpersonal therapy were most effective in preventing relapse when started following an acute manic or depressive episode. Cognitive behavioural therapy and group psychoeducation were effective strategies for relapse prevention when initiated during stable periods. Psychotherapies and psychosocial interventions emphasising medication adherence and early recognition of mood symptoms were more effective in preventing recurrences of mania, and cognitive and interpersonal approaches had greater success in preventing depressive relapses. A specialised psychological intervention called ‘enhanced relapse prevention’ is aimed at recognising and managing the early warning signs of depressive or manic episodes by improving patients’ understanding of BD, enhancing therapist–patient relationships, and optimising ongoing treatment. A study using qualitative interviews found that both therapists and their bipolar patients believe that enhanced relapse prevention increases awareness of early warning signs of recurring illness, leading to effective changes in medication management and fewer relapses.21

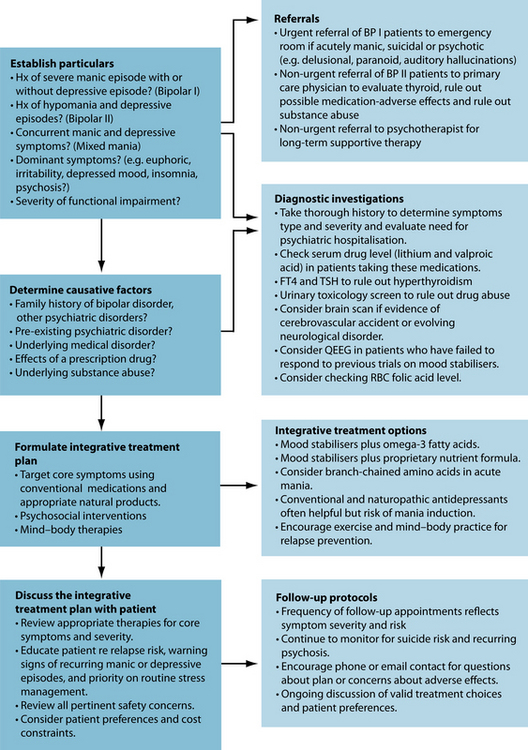

INTEGRATIVE MEDICAL DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OPTIONS

INTEGRATIVE MEDICAL TREATMENT AIMS

A significant percentage of individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder use non-pharmacological modalities together with prescription medications; however, there is relatively little evidence for the safety and efficacy of most non-conventional treatments.22,23 The most appropriate and effective integrative treatment approach is determined by the type and severity of symptoms, the presence of comorbid medical or psychiatric disorders, response to previous treatments, patient preferences and constraints on cost and availability of treatments. When prominent symptoms of anxiety, psychosis or agitation are present, effective integrative strategies should prioritise treatment of those symptoms. For example, reasonable integrative approaches when managing an acutely manic patient who is agitated and extremely anxious include an initial loading dose of valproic acid or another conventional mood stabiliser, high potency benzodiazepines, an antipsychotic that is sedating (at bedtime), and possibly also amino acids known to have calming or sedating effects, such as L-tryptophan, 5-HTP or L-theanine.

While CAM interventions appear to have limited activity in treating the hypomanic or manic phase of BD, they may have benefit in treating BD depression as monotherapies or as adjuvant treatments with synthetic antidepressants.24

Nutritional medicines

Adding L-tryptophan 2–3 g/day or 5-HTP 25 to 100 mg up to three times a day may have beneficial effects on anxiety associated with mania.25,26 L-tryptophan 2 g can be safely added to mood stabilisers at bedtime and may improve sleep quality in agitated manic patients. Doses as high as 15 g may be required when insomnia is severe (although this should be closely monitored, and this dosage may be restricted in some countries).27 When added to sedating antidepressants (such as trazodone) taken at bedtime L-tryptophan 2 g may accelerate antidepressant response and improve sleep quality.28 Serious adverse effects have not been reported using this protocol. L-theanine reduces state anxiety by increasing alpha activity and increasing synthesis of GABA.29,30 Noticeable anxiety reduction is generally achieved within 30 to 40 minutes and effective doses range between 200 mg and 800 mg/day.

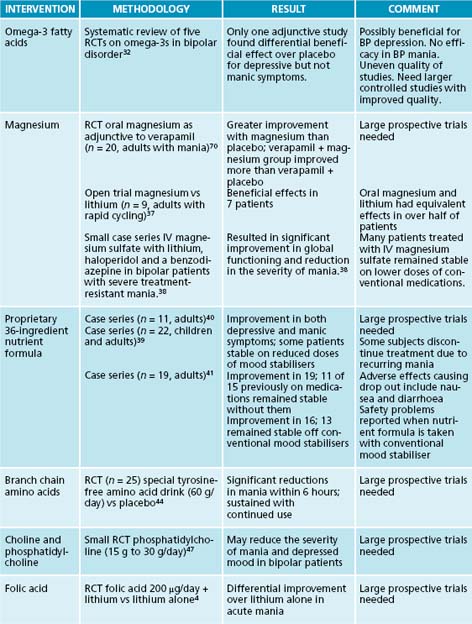

Countries where there is high fish consumption have relatively lower prevalence rates of BD.31 A systematic review of controlled trials on omega-3 fatty acids in BD that used rigorous inclusion criteria identified only one study in which omega-3s used adjunctively with a mood stabiliser showed a differential beneficial effect on depressive but not manic symptoms.32 The reviewers cautioned that any conclusions about the efficacy of omega-3 fatty acids in bipolar disorder must await larger controlled studies of improved methodological quality. Large doses of omega-3 fatty acids may be more effective in the depressive phase of the illness.33 Rare cases of increased bleeding times, but not increased risk of bleeding, have been reported in patients taking aspirin or anti-coagulants together with omega-3s. Some studies suggest that the omega-3 essential fatty acid EPA at doses between 1 and 4 g/day may have beneficial adjuvant effects when added to certain atypical antipsychotics;34,35 however, one placebo-controlled trial did not confirm an adjuvant effect.36 In contrast, the appropriate management of a severely depressed bipolar patient might include an integrative regimen that combines a mood stabiliser with an antidepressant and omega-3 fatty acids. Gradually titrating stable bipolar patients on a proprietary nutrient formula (see Table 33.1 for review of the evidence) while continuing them on their conventional mood stabiliser may result in improved outcomes, reductions in therapeutic doses in some cases, lower adverse effects rates and improved treatment adherence.

Magnesium may be an effective adjunctive therapy for treatment of acute mania or rapidly cycling bipolar disorder. In a small open trial, oral magnesium supplementation had comparable efficacy to lithium in rapid cycling bipolar patients.37 In a small case series intravenous magnesium sulfate used adjunctively with lithium, haloperidol and a benzodiazepine in bipolar patients with severe treatment-resistant mania resulted in significant improvement in global functioning and reduction in the severity of mania.38 Many patients treated with IV magnesium sulfate remained stable on lower doses of conventional medications.

A proprietary 36-ingredient formula of vitamins and minerals may significantly reduce symptoms of mania, depressed mood and psychosis in bipolar patients when taken alone or used adjunctively with conventional mood stabilisers.39,40,41 Researchers believe the formula works by correcting inborn metabolic errors that result in bipolar-like symptoms in genetically predisposed individuals when certain micronutrients are deficient in the diet.40 In one series, 11 bipolar patients who completed a 6-month protocol were able to reduce their conventional mood stabilisers by half while improving clinically. In another case series, 13 out of 19 bipolar patients who continued on the nutrient formula remained stable after discontinuing conventional mood stabilisers.42 Some patients stopped taking the formula because of nausea and diarrhoea and three patients resumed conventional mood stabilisers because of recurring manic symptoms. Two randomised placebo-controlled double-blind studies are ongoing at the time of writing with the goal of determining whether the nutrient formula is an effective stand-alone treatment and identifying the most efficacious combination of nutrients and optimum dosing strategies for different phases of bipolar illness. Recent concerns have been raised over safety problems reported when the nutrient formula is taken together with a conventional mood stabiliser.39

Bipolar patients may be genetically susceptible to mood swings when certain amino acids are unavailable in the diet. Findings of two small randomised controlled trials (RCTs) suggest that certain branch-chain amino acids may rapidly improve acute mania by interfering with synthesis of norepinephrine and dopamine.43,44 In one study 25 bipolar patients randomised to a special tyrosine-free amino acid drink (60 g/day) versus placebo experienced significant reductions in the severity of mania within 6 hours.44 Improvements in mania were sustained with repeated administration of the amino acid drink. Restricting or excluding L-tryptophan from the diet may increase the susceptibility of bipolar patients to depressive mood swings; however, research findings to date are highly inconsistent.45

Choline is necessary for the biosynthesis of acetylcholine (Ach) and abnormal low brain levels of acetylcholine may cause some cases of mania.46 Findings of a small RCT suggest that phosphatidylcholine (15 g to 30 g/day) may reduce the severity of mania and depressed mood in bipolar patients.47 Findings of a RCT suggest that supplementation with folic acid 200 μg/day may enhance the beneficial effects of lithium carbonate in acutely manic patients.4 Many case reports and case series suggest that choline (a B complex vitamin) reduces the severity of mania. It has been postulated that abnormal low brain levels of Ach are a primary cause of mania.46 In a small case study of treatment-refractory, rapid-cycling bipolar patients who were taking lithium, four out of six people responded to the addition of 2000–7200 mg/day of free choline. It should be noted that two non-responders were also taking hypermetabolic doses of thyroid medication. Clinical improvement correlated with increased intensity of the basal ganglia choline signal as measured on proton magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The effect of choline on depressive symptoms was variable.47 Case reports, open trials and one small double-blind study suggest that supplementation with phosphatidylcholine 15 g to 30 g/day reduces the severity of both mania and depressed mood in bipolar patients, and that symptoms recur when phosphatidylcholine is discontinued.46,47 Findings of a double-blind study suggest that folic acid 200 μg/day may enhance the beneficial effects of lithium carbonate in acutely manic patients.4,48

Findings of a small open study suggest that patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder who exhibit mania or depressed mood respond to low doses (50 μg with each meal) of a natural lithium preparation.49 Posttreatment serum lithium levels were undetectable in patients who responded to trace lithium supplementation. Findings of a small pilot study suggest that magnesium supplementation 40 mEq/day may be as effective as lithium in the treatment of rapidly cycling bipolar patients.37

Findings from animal research and a small open study suggest that bipolar patients who take potassium 20 mEq twice daily with their conventional lithium therapy experience fewer side effects, including tremor, compared to patients who take lithium alone.50 No changes in serum lithium levels were reported in patients taking potassium. Pending confirmation of these findings by a larger double-blind trial, potassium supplementation may provide a safe, cost-effective integrative approach for the management of bipolar patients who are unable to tolerate therapeutic doses of lithium due to tremor and other adverse effects. Patients who have cardiac arrhythmias or are taking antiarrhythmic medications should consult with their physicians before considering taking a potassium supplementation.

Herbal medicines

A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials comparing Hypericum perforatum to placebo or conventional antidepressants suggests that hypericum and standard antidepressants have similar beneficial effects.51 This herb may be beneficial in the depressive phase of BD; however, no studies on this have currently been conducted. Several case reports of mania induction with H. perforatum52,53 and potential serious interactions with many drugs54 have resulted in limited use of this herbal for the treatment of BD. Findings of a large 12-week placebo-controlled trial suggest that a proprietary Chinese compound herbal formula consisting of at least 11 herbals may be a beneficial adjuvant of conventional mood stabilisers for treatment of the depressive phase of bipolar disorder.55 Bipolar depressed (but not manic) patients randomised to the herbal formula plus a conventional mood stabiliser experienced significantly greater reductions in the severity of depressed mood compared to matched patients receiving a mood stabiliser only. These findings were replicated in a subsequent study, which confirmed that bipolar depressed patients treated with the herbal formula only improved more than patients treated with a placebo.56 Early studies suggested that the Ayurvedic herbal Rauwolfia serpentina was an effective treatment of bipolar disorder that augmented the antimanic efficacy of lithium without risk of toxic interactions.57,58 However, use of this herbal in Western countries is now very restricted because of safety concerns.

Therapeutic considerations

Conventional pharmacological treatments of the depressive and manic phases of BD have a mixed record of success. This is due to both high rates of treatment discontinuation and limited efficacy when treatment is adhered to. Furthermore, less severe symptoms of mania are often unreported or mis-diagnosed as anxiety disorders or sleep disorders, resulting in erroneous diagnoses of agitated depressed mood or other psychiatric disorder and, subsequently, inappropriate and ineffective treatment.59 Fewer

than half of patients who take conventional maintenance treatments following an initial manic episode report sustained control of their symptoms.60 Furthermore, as many as 40% of bipolar patients who adhere to pharmacological treatment experience recurring manic or depressive mood swings while taking medications at recommended doses.61 Only about half of all conventional medications used to treat BD are supported by strong evidence.62 As many as half of all bipolar patients who take mood stabilisers do not experience good control of their symptoms or refuse to take medications, and approximately 50% discontinue their medications because of serious adverse effects including tremor, weight gain, elevated liver enzymes and others.63 Due to this CAM therapies may have a potential role in improving quality of life, reducing side effects and improving compliance.

A significant percentage of bipolar patients relapse while taking conventional mood stabilisers for long-term maintenance. A systematic review of RCTs comparing valproic acid with lithium carbonate and other mood stabilisers found that valproic acid has equivocal efficacy as a long-term maintenance therapy of BD.64 A systematic review of placebo-controlled trials of adjunctive pharmacological treatments of bipolar disorder concluded that combining a mood stabiliser with a conventional antidepressant does not improve outcomes compared to outcomes obtained with a single mood stabiliser.65 An emerging conventional treatment of BD, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), may be an effective treatment of the depressive phase of BD; however, the findings of sham-controlled trials are inconsistent.66,67

Example treatment

Due to the patient being diagnosed with bipolar I, an integrative treatment plan that includes pharmaceutical medication is required. Lithium carbonate and a sedating atypical antipsychotic (at bedtime) are example synthetic treatments for BP I, while omega-3 essential fatty acids, a B-vitamin complex (high in folic acid) may provide adjuvant support. Preliminary evidence suggests that listening to soothing music or binaural sounds can also significantly reduce symptoms of anxiety.68,69 Consideration of antidepressant medications (natural or synthetic) may be advised to treat her depression; however, she would be needed to be closely monitored for potential ‘switching’ to a manic phase. If her sleep pattern is poor, various herbal or nutritional interventions in addition to sleep hygiene advice may be of benefit (see the case in Chapter 14 on insomnia).

Expected outcomes and follow-up protocols

When approaching an acutely manic patient the principal treatment goals are patient safety and rapid stabilisation, frequently requiring psychiatric hospitalisation. Atypical antipsychotics are probably the most effective and efficient conventional treatments of severe mania and accompanying psychosis, and generally result in stabilisation within hours or days. ‘Loading’ a manic patient with a conventional mood stabiliser (such as lithium or valproic acid) to rapidly achieve a therapeutic serum level is an effective strategy for the management of acute mania. Omega-3 fatty acids can be used adjunctively during the initial stages of treatment and may permit lower effective doses of

mood stabilisers, reduced incidence of treatment-emergent adverse effects and improved medication compliance over the long term. Residual symptoms of insomnia can be managed using melatonin, improved sleep hygiene and guided imagery. Regular exercise and a mind–body practice provide a healthy preventative framework for bipolar patients. After stabilisation has been achieved with conventional medications it may be possible to gradually reduce doses of conventional medications in bipolar patients who are responding to adjunctive therapies, including a proprietary multinutrient formula and omega-3 essential fatty acids. In such cases, clinical management decisions should always be made in the context of close monitoring for treatment-emergent adverse effects or interactions, and warning signs of recurring manic or depressive episodes. Ongoing psychoeducation or psychosocial interventions enhance treatment adherence and help bipolar patients recognise and respond to early warning signs of relapse.

KEY POINTS

American Psychiatric Association. Practice guidelines for treatment of patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(12, Supplement):1-36. iv

Andreescu C. Complementary and alternative medicine in the treatment of bipolar disorder—a review of the evidence. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2008;110(1):16-26.

Lake J. Textbook of integrative mental health care. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers, 2006.

Sarris J. Adjuvant use of nutritional and herbal medicines with antidepressants, mood stabilisers and benzodiazepines. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2009;44(1):32-41.

1. Robins L., Regier D., editors. Psychiatric disorders in America: the epidemiologic catchment area study. New York: Free Press, 1991.

2. Gurling H. Linkage findings in bipolar disorder Nat Genet. 1995;8–9:10.

3. Konradi C. Molecular evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction in bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:300-308.

4. Hasanah C.I., et al. Reduced red-cell folate in mania. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1997;46:95-99.

5. Small J.G. Topographic EEG studies of mania. Clinical Electroencephalography. 1998;29(2):59-66.

6 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

7. Winokur G. Manic depressive illness. St Louis: C.V. Mosby; 1969.

8. Judd L., et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(6):530-537.

9. Vieta E., Phillips M.L. Deconstructing bipolar disorder: a critical review of its diagnostic validity and a proposal for DSM-V and ICD-11. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(4):886-892.

10. Ilgen M.A. A collaborative therapeutic relationship and risk of suicidal ideation in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2008;115(1):246-251.

11. Culver J.L. Bipolar disorder: improving diagnosis and optimizing integrated care. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63(1):73-92.

12. Perlick D.A. Symptoms predicting inpatient service use among patients with bipolar affective disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50(6):806-812.

13. Altamura A.C., Goikolea J.M. Differential diagnoses and management strategies in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4(1):311-317.

14. Miklowitz D.J., Johnson S.L. The psychopathology and treatment of bipolar disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psycholz. 2006;2:199-235.

15. Benjamin A.B. A unique consideration regarding medication compliance for bipolar affective disorder: exercise performance. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(8):928-929.

16. Lakhan S.E., Vieira K.F. Nutritional therapies for mental disorders. Nutr J. 2008;21(7):2.

17 American Psychiatric Association. Practice guidelines: Treatment of patients with bipolar disorder. 7th edn. Available: http://www.psychiatryonline.com/pracGuide/pracGuideTopic_8.aspx

18. Cousins D.A., Young A.H. The armamentarium of treatments for bipolar disorder: a review of the literature. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;10(3):411-413.

19. Rodriguez-Martin J.L. Transcranial magnetic stimulation for treating depression. Cochrane Depression Anxiety and Eurosis Group. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews. 4, 2001. CD003493

20. Miklowitz D.J. Adjunctive psychotherapy for bipolar disorder: state of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(11):1408-1419.

21. Pontin E. Enhanced relapse prevention for bipolar disorder: a qualitative investigation of value perceived for service users and care coordinators. Implement Sci. 2009;9(4):4.

22. Ernst E. Complementary medicine: where is the evidence? J Fam Pract. 2003;52:630-634.

23. Dennehy E. Self-reported participation in nonpharmacologic treatments for bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65(2):278.

24. Sarris J. Adjuvant use of nutritional and herbal medicines with antidepressants, mood stabilizers and benzodiazepines. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2009. In press

25. Soderpalm B., Engel J.A. erotonergic involvement in conflict behavior. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1990;1(1):7-13.

26. Kahn R.S., et al. Effect of a serotonin precursor and uptake inhibitor in anxiety disorders; a double-blind comparison of 5-hydroxytryptophan, clomipramine, and placebo. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1987;2(1):33-45.

27. Schneider-Helmert D., Spinweber C.L. Evaluation of L-tryptophan for treatment of insomnia: a review. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1986;89(1):1-7.

28. Levitan R.D. Preliminary randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of tryptophan combined with fluoxetine to treat major depressive disorder: antidepressant and hypnotic effects. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 2000;4:337-346.

29. Kakuda T., et al. Inhibiting effects of theanine on caffeine stimulation evaluated by EEG in the rat. Biosci Biotechno Biochem. 2000;64:287-293.

30. Mason R. 200 mg of Zen; L-theanine boosts alpha waves, promotes alert relaxation. Alternative and Complementary Therapies. 2001;7:91-95.

31. Hibbeln J.R. Seafood consumption, the DHA content of mothers’ milk and prevalence rates of postpartum depression: a cross-national, ecological analysis. J Affect Disord. 2002;69:15-29.

32. Montgomery P., Richardson A.J. Omega-3 fatty acids for bipolar disorder. Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews. 2, 2008. CD005169

33. Chiu C.C., et al. Omega-3 fatty acids are more beneficial in the depressive phase than in the manic phase in patients with bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1613-1614.

34. Emsley R. Randomized, placebo-controlled study of ethyl-eicosapentaenoic acid as supplemental treatment in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;1859:1596-1598.

35. Peet M., Horrobin D.F. (E-E Multicentre Study Group). A dose-ranging exploratory study of the effects of ethyl-eicosapentaenoate in patients with persistent schizophrenic symptoms. J Psychiatr Res. 2002;36(1):7-18.

36. Fenton W.S., et al. A placebo-controlled trial of omega-3 fatty acid (ethyl eicosapentaenoic acid) supplementation for residual symptoms and cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(12):2071-2073.

37. Chouinard G. A pilot study of magnesium aspartate hydrochloride (Magnesiocard) as a mood stabilizer for rapid cycling bipolar affective disorder patients. Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology Biology and Psychiatry. 1990;4:171-180.

38. Heiden A. Treatment of severe mania with intravenous magnesium sulphate as a supplementary therapy. Psychiatry Res. 1999;89(3):239-246.

39. Popper C. Do vitamins or minerals (apart from lithium) have mood-stabilizing effects? J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(12):933-935.

40. Kaplan B.J., et al. Effective mood stabilization with a chelated mineral supplement: an open-label trial in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:936-944.

41. Simmons M. Nutritional approach to bipolar disorder [Letter to the editor]. Jour Clin Psychiatry. 2002;64:338.

42. Simmons M. Nutritional approach to bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2003;64(3):338.

43. Barrett S., Leyton M. Acute phenylalanine/tyrosine depletion: a new method to study the role of catecholamines in psychiatric disorders. Primary Psychiatry. 2004;11(6):37-41.

44. Scarna A. Effects of a branched-chain amino acid drink in mania. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;182:210-213.

45. Hughes J. Effects of acute tryptophan depletion on cognitive function in euthymic bipolar patients. Eur Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;12(2):123-128.

46. Leiva D. The neurochemistry of mania: a hypothesis of etiology and rationale for treatment. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1990;14(3):423-429.

47. Stoll A.L. Choline in the treatment of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder: clinical and neurochemical findings in lithium-treated patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40:382-388.

48. Coppen A., et al. Folic acid enhances lithium prophylaxis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1986;10(1):9-13.

49. Fierro A. Natural low dose lithium supplementation in manic-depressive disease. Nutr Perspectives. 1988:10-11.

50. Tripuraneni B. Clin Psychiatry News. 1990;18(10):3. presented to the 143rd Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, 12–17 May 1990, abstracts NR 100 and NR 210

51. Linde K. St John’s wort for major depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2008;. CD000448

52. Moses E.L., Mallinger A.G. St. John’s Wort: three cases of possible mania induction. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;20(1):115-117.

53. Fahmi M. A case of mania induced by hypericum. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2002;3(1):58-59.

54. Izzo A.A. Drug interactions with St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum): a review of the clinical evidence. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;42(3):139-148.

55. Zhang Z.J., et al. Adjunctive herbal medicine with carbamazepine for bipolar disorders: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41(3–4):360-369.

56. Zhang Z.J., et al. The beneficial effects of the herbal medicine Free and Easy Wanderer Plus (FEWP) for mood disorders: double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:828-836.

57. Bacher N.M., Lewis H.A. Lithium plus reserpine in refractory manic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136(6):811-814.

58. Berlant J.L. Neuroleptics and reserpine in refractory psychoses. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1986;6(3):180-184.

59. Benazzi F. Prevalence of bipolar II disorder in outpatient depression: a 203-case study in private practice. J Affect Disord. 1997;43(2):163-166.

60. Tohen M. Outcome in mania: a 4-year prospective follow-up on 75 patients utilizing survival analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:1106-1111.

61. Strober M. Relapse following discontinuation of lithium maintenance therapy in adolescents with bipolar I illness: a naturalistic study. Am J of Psychiatry. 1990;147:457-461.

62. Boschert S. Evidence-based treatment largely ignored in bipolar disorder. Clinical Psychiatry News. 1, June 2004.

63. Fleck D.E. Factors associated with medication adherence in African American and white patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:646-652.

64. Macritchie K.A. Valproic acid, valproate and divalproex in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews. (3):CD003196):2008;.

65. Ghaemi S.N. Effectiveness and safety of long-term antidepressant treatment in bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;62(7):565-569.

66. Nahas Z. Left prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) treatment of depression in bipolar affective disorder: a pilot study of acute safety and efficacy. Bipolar Disorders. 2003;5(1):40-47.

67. Kaptsan A. Right prefrontal TMS versus sham treatment of mania: a controlled study. Bipolar Disorders. 2003;5(1):36-39.

68. Kerr T. Emotional change processes in music-assisted reframing. Journal of Music Therapy. 2001;38(3):193-211.

69. Atwater, F. The Hemi-Sync process. Research Division, The Monroe Institute, 1999. Online. Available: http://store.hemisyncforyou.com/v/hemisync-cd-process.html

70. Giannini A.J. Magnesium oxide augmentation of verapamil maintenance therapy in mania. Psychiatry Research. 2000;93:83-87.