CHAPTER 7 Bipolar and related disorders

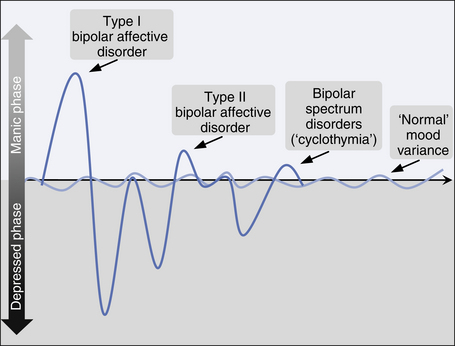

Bipolar mood disorders (BD) are characterised by the occurrence of elevated mood and (usually) depressed mood, either at different times or simultaneously (see Table 7.1 and Box 7.1). The precise delineation between ‘normal’ mood swings, mood instability as part of a personality disorder, and mood swings which are an indicator of bipolar disorder, is complex. As in all mood disorders, the disruption of normal mood is not the only or even necessarily the most prominent element of the disorder.

TABLE 7.1 Features of bipolar affective disorder according to DSM–IVTR and ICD–10

BOX 7.1 Core elements of bipolar disorder

Clinical features

Mania

Mania is a mental state in which motivation, energy, mood and/or thinking are elevated. The need for sleep is reduced, thought content is more grandiose, speed of thinking is increased, but thoughts remain connected (‘flight of ideas’), distractibility is high, libido is increased, behaviour is more socially disinhibited (including excessive spending of money), judgment is impaired and often the person is more physically active than usual. The person is often intolerant of challenge and may become aggressive if frustrated. This can pose a major problem for ‘significant others’ when faced with very inappropriate behaviour.

Depressed phase of bipolar disorder

The clinical presentation is essentially the same as in depressive disorders (see Ch 6), but is more likely to be severe, and associated somatic (melancholic) features are more likely. Abrupt onset of a severe melancholic depression in a young person (particularly an adolescent) may be a harbinger of bipolar disorder, and careful monitoring of antidepressant response (to check for manic switch) is required. ‘Atypical’ depressive clinical features are more common in bipolar disorders than other mood disorders. The different phases of illness are shown in Figure 7.1.

Course of bipolar disorders

In bipolar I disorder, episodes of both mania and severe depression occur. Bipolar II disorder is characterised by episodes of hypomania, interspersed by separate and often severe episodes of depression. Rapid cycling bipolar disorder refers to a subset of patients with either bipolar I or bipolar II disorder whose illness includes more than four episodes of both mania/hypomania and depression per year. This form of the illness is particularly disruptive and may be provoked by substances such as antidepressant medications and stimulants.

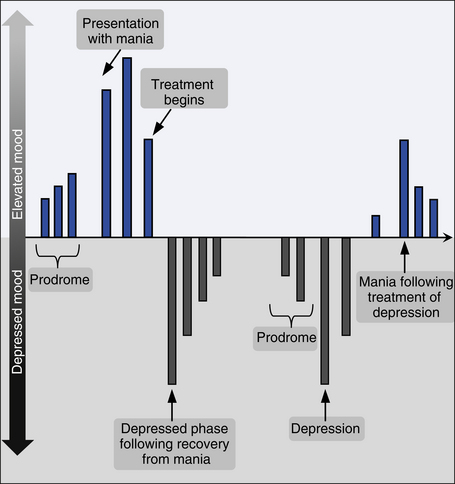

Depressive episodes are the most common state in bipolar disorders, but a very small group of people will suffer only manic symptoms. The most common sequence is for mania and/or hypomania to be followed by depression, but the reverse also occurs. Depression followed by mania or hypomania is often more resistant to mood stabilisers than the opposite sequence. Manic symptoms become less common with age in bipolar individuals and mixed manic and depressive symptoms more common. Figure 7.2 is a pictorial representation of a patient with bipolar I.

Mixed bipolar states

Manic or hypomanic symptoms may arise simultaneously with depressive symptoms in a mixture which is easily overlooked. Sometimes, manic and depressive symptoms will arise in close succession and at other times symptoms of mania or hypomania may be present and combined with depressed mood or negative thought content. The affect is often irritable rather than euphoric.

Schizoaffective disorder

When an individual has presented with clear features of schizophrenia (see Ch 5) and at other times clear features of mania, a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder can be considered. This is a controversial concept and illustrates the limitations of our current diagnostic system.

Bipolar spectrum disorders

CASE EXAMPLES: bipolar disorders

A 40-year-old man with a 20-year history of bipolar affective disorder (type I) telephoned his psychiatrist to say he was about to board an aircraft to fly to Canberra to advise the prime minister that the world was at serious risk. He mentioned that he wanted his psychiatrist to know so that they would not worry because he would not be keeping his appointment that day. There was no need to send further prescriptions of his medications as he had found a new machine that used magnetic fields to improve his thinking and he had been managing much better off all medication. He was subsequently arrested in parliament. Management: He required compulsory treatment in a psychiatric hospital. Treatment consisted of a sedative antipsychotic and reintroduction of his mood stabiliser. Regrettably, although this was effective at reversing his manic episode, he became psychotically depressed and required a course of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). He required a complex combination of medications to keep him well and underwent extensive psychological treatment.

Differential diagnoses

Personality disorders

In some circumstances, severe personality disruption can be accompanied by unpredictable fluctuations in mood, self-evaluation and behaviour. These ‘highs’ and ‘lows’ can be confused with bipolar disorder, but are usually distinguished by the links to life events, their brevity and strong response to changes in life circumstance (see Ch 12).

Aetiology of bipolar disorders

Genetic factors

Genetic processes contribute significantly to bipolar disorders, with first degree relatives having approximately seven times the risk of developing a bipolar disorder and twice the risk of developing unipolar depression compared to the general population. Twin studies have revealed 67% concordance in monozygotic twins and 19% in dizygotic twins. Unipolar depression is also overrepresented in these monozygotic twins. In adoption studies, bipolar and unipolar mood disorders both appear more common in the biological relatives of adopted children than the families of adopting parents.

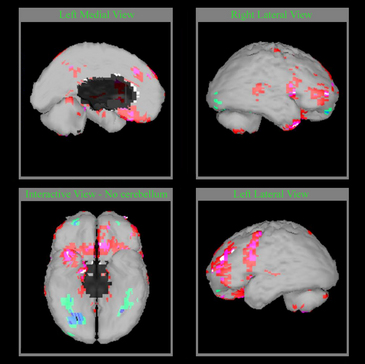

Neuroimaging

Figure 7.3 shows computer-generated images of a single photon emission computerised tomography (SPECT) scan of a patient with mania.

Management of bipolar disorders

Management of mania

Mania is managed as an acute psychosis, but euphoria can rapidly change to rage and aggression when a person is confronted with proposed treatment and containment, however benevolent. An explanation of the need for treatment is essential, but is often not accepted by patients who are psychotic, and compulsory treatment may be required. Once the diagnosis has been made and the need for treatment established, the therapist must proceed as quickly as possible to administer effective treatment.

Medications should include an antipsychotic agent (see Ch 13) and sometimes extra sedation in the form of a benzodiazepine. Some patients will accept oral medications and this is clearly preferable, but parenteral administration may be required.

Response to treatment with antipsychotic medications in mania is usually rapid, but relapse may occur if medications are reduced too quickly or adherence is poor. Many sufferers will subsequently move directly into a depressed phase of illness, but it will often be sufficient to persist with a mood stabiliser as the mood instability settles. The management of hypomania essentially follows the same principles, but the patient is usually (not always) more accepting of treatment with medications. A brief summary of management strategies in mania is provided in Box 7.2.

BOX 7.2 Summary of management strategies

Mania

Sometimes, mania may not respond well to medications and ECT can be invaluable (see Ch 13).

Management of bipolar depression

The management of bipolar depression is best achieved using mood stabilisers, including second generation antipsychotic medications. There is evidence that quetiapine appears particularly effective and ziprasidone may also be effective. Antidepressants which are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), particularly those with very little noradrenergic effect such as citalopram and escitalopram, appear less likely to provoke manic switching than noradrenaline and specific serotonergic agents (NASAs), serotonergic and noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, selective noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors (NRIs) and irreversible monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) (see Ch 13).

ECT is invaluable in the management of bipolar depression when the severity is high and particularly when psychotic symptoms are evident.

Management of bipolar spectrum disorders

The decision to treat with medication requires negotiation with the patient and perhaps their partner or families, as some may prefer to cope with psychological assistance alone or tolerate the mood swings without further intervention. Citalopram/escitalopram or lamotrigine appear particularly helpful. A brief summary of biological interventions in bipolar disorders is provided in Box 7.3.

BOX 7.3 Summary of biological interventions

Psychosocial interventions in the management of bipolar disorders

Individual and group psychotherapy, which may use a variety of treatment models, are very helpful with psychological adaptation to bipolar disorders and in the reduction of vulnerability to the precipitants of illness episodes. Identification of specific stresses and their meaning to patients is invaluable. See Chapter 14 for further detail about specific therapeutic techniques.

Box 7.4 provides a summary of psychosocial interventions.

References and further reading

Brown E.S., editor. Bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2005.

Goodwin F., Jamison K. Manic-depressive illness. Bipolar disorders and recurrent depression. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007.

Jamison K. An unquiet mind. New York: Knopf; 1995.

Joyce P., Mitchell P., editors. Mood disorders: recognition and treatment. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2004.

Parker G. Bipolar II disorder. In modelling, measuring and managing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008.