CHAPTER 21 Biopsychosocial Issues in Gastroenterology

CONCEPTUALIZATION OF GASTROINTESTINAL ILLNESS

BIOMEDICAL MODEL

In the practice of medicine, feeling confused, even stuck, when discrepancies exist between what we observe and what we expect is not uncommon. This experience may occur when diagnosing and caring for a patient who has symptoms that do not match our understanding of the degree of disease. In Western civilization, the traditional understanding of illness (the personal experience of ill health or bodily dysfunction, as determined by current or previous disease as well as psychosocial, family, and cultural influences) and disease (abnormalities in structure and function of organs and tissues)1 has been termed the biomedical model.2 This model adheres to two premises. The first is that any illness can be linearly reduced to a single cause (reductionism). Therefore, identifying and modifying the underlying cause is necessary and sufficient to explain the illness and ultimately lead to cure. The second is that an illness can be dichotomized to a disease, or organic disorder, which has objectively defined pathophysiology, or a functional disorder, which has no specifically identifiable pathophysiology (dualism). This dichotomy presumes to distinguish medical (organic) from psychological (functional) illness or relegates functional illness to a condition with no cause or treatment.

The limitations of this model are now becoming evident; modern research has shown a blurring of this dichotomy,3,4 as illustrated by the following case history.

This case of a patient with a severe functional GI disorder5,6 can be challenging when approached from the biomedical model. In addition to difficulties in diagnosis and management, strong feelings may occur that are maladaptive to the physician-patient relationship, for several reasons.7 First, the physician and patient approach the problem using a functional-organic dichotomy. With no evidence of a structural (organic) diagnosis to explain the symptoms for over 20 years, the patient still urges that further diagnostic studies be done to “find and fix” the problem, and the physician orders an upper endoscopy. However, failure to find a specific structural cause for medical symptoms is the rule rather than the exception in ambulatory care. In a study involving 1000 ambulatory internal medicine patients,8 only 16% of 567 new complaints (and only 11% for abdominal pain) over a three-year period were eventually found to have an organic cause, and only an additional 10% were given a psychiatric diagnosis. This patient has functional abdominal pain syndrome,9,10 one of 27 adult functional GI disorders11 that comprise over 40% of a gastroenterologist’s practice (see Chapter 11).12 Mutual acceptance of this entity as a real diagnosis is the key to beginning a proper plan of care. Because functional GI disorders do not fit into a biomedical construct (i.e., they are seen as an illness without evident disease),4 the risk that unneeded and costly diagnostic tests will be ordered to find the cause continues, as illustrated by the physician’s ordering another upper endoscopy. This approach may deflect attention away from the direction of proper management.

Second, psychosocial features are evident, including major loss, depression, abuse history, and maladaptive thinking (i.e., catastrophizing and perceived inability to manage the symptoms), in addition to the possible development of narcotic bowel syndrome (see Chapter 11), which adversely influence the clinical outcome and are amenable to proper treatment.13–15 These features are ignored or minimized, however, reflecting that patients and physicians tend to view psychosocial factors as separate from, and often less important than, medical illness.16 In reality, the psychosocial features are so relevant to the illness presentation that by addressing them the patient may improve. Ultimately, the physician, possibly recognizing that these issues are important, may feel unable to manage the problems and refers Ms. L to a psychiatrist. In turn, the psychiatrist also approaches the problem dualistically, noting the depression but also indicating uncertainty and even concern as to whether a medical diagnosis has been overlooked. These competing viewpoints may only confuse the patient.

Third, difficulties exist in the physician-patient interaction. The patient’s and physician’s goals and expectations for care are at odds. Whereas the patient wants a quick fix, the physician sees the condition as chronic and ultimately requiring psychiatric intervention, not narcotics, which could do harm.15 In response, the patient requests referral to another facility. This maladaptive interaction and poor communication relating to differing understandings of the illness and its treatment could have been avoided by addressing these differing views and mutually negotiating a plan of diagnosis and care.

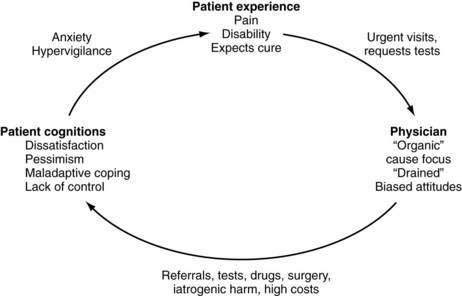

This “vicious cycle” of ineffective care (Fig. 21-1) results from the limitations imposed by the biomedical model. The vicious cycle occurs not only among patients with functional GI disorders, but also among patients with organic disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In such cases, pain and diarrhea are not explained by the degree of disease activity, and the patient likely has irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) as well (so-called IBD-IBS; see Chapters 111, 112, and 118).3 The reality is that (1) medical disorders and patient symptoms are inadequately explained by structural abnormalities; (2) psychosocial factors predispose to the onset and perpetuation of illness and disease, are part of the illness experience, and strongly influence the clinical outcome regardless of diagnosis; and (3) successful application of this understanding and proper management require an effective physician-patient relationship.

BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL MODEL

The biopsychosocial model2,16 proposes that illness and disease result not from a single cause, but from simultaneously interacting systems at the cellular, tissue, organism, interpersonal, and environmental levels. Furthermore, psychosocial factors have direct physiologic and pathologic consequences, and vice versa. For example, change at the subcellular level (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus infection or susceptibility to IBD) has the potential to affect organ function, the person, the family, and society. Similarly, a change at the interpersonal level, such as the death of a spouse, can affect psychological status, cellular immunity, and, ultimately, disease susceptibility.17 The model also explains why the clinical expression of biological substrates (e.g., alterations in oncogenes) and associated responses to treatment vary among patients. The biopsychosocial model is consistent with emerging scientific data about the mechanisms of disease and clinical care and is assumed to be valid in this discussion.

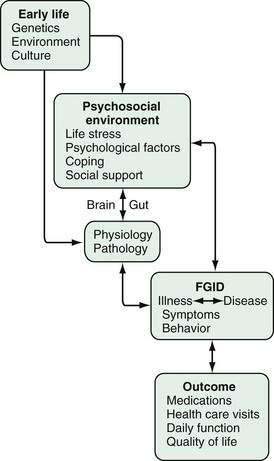

Figure 21-2 provides the framework for understanding the mutually interacting relationship of psychosocial and biological factors in the clinical expression of illness and disease. Early life factors (e.g., genetic predisposition, early learning, cultural milieu) can influence an individual’s later psychosocial environment, physiologic functioning, and disease (pathologic) expression, as well as reciprocal interactions via the brain-gut (central nervous system [CNS]–enteric nervous system [ENS]) axis. The product of this brain-gut interaction will affect symptom experience and behavior, and ultimately the clinical outcome. Figure 21-2 will serve as a template for the outline and discussion that follows.

EARLY LIFE

EARLY LEARNING

Developmental Aspects

Certain GI disorders may be influenced by learning difficulties or emotionally conflicting or challenging interactions that occur early in life. These disorders include rumination syndrome (see Chapter 14),18 anorexia nervosa (see Chapter 8),19 functional (psychogenic) vomiting (see Chapter 14),20 and constipation (see Chapter 18), all of which can develop based on early conditioning experiences. Disorders of anorectal function (e.g., pelvic floor dyssynergia and encopresis) also may have resulted from learning difficulties relating to bowel habit21 or abuse (see Chapters 17 and 18).22 Encopretic children may withhold stool out of fear of the toilet, to struggle for control, or to receive attention from parents.23 One study has proposed that encopretic children are more likely than controls to have been toilet-trained by coercive techniques, have psychological difficulties, and have poor rapport with their mothers.24

Well-designed studies have supported the role of early modeling of symptom experience and behavior in the clinical expression of GI symptoms and disorders.14 In particular, childhood sexual and physical abuse can have physical consequences, thereby affecting the development or severity of functional GI disorders,25 and early family attention toward GI symptoms and other illnesses can influence later symptom reporting, health behaviors, and health care costs.26

Physiologic Conditioning

Early conditioning experiences may also influence physiologic functioning and possibly the development of psychophysiologic disorders. Psychophysiologic reactions involve psychologically induced alterations in the function of target organs without structural change. They often are viewed as physiologic concomitants of an affect such as anger or fear, although the person is not always aware of the affect. The persistence of an altered physiologic state or the enhanced physiologic response to psychologic stimuli is considered by some as a psychophysiologic disorder. Visceral functions such as the secretion of digestive juices and motility of the gallbladder, stomach, and intestine can be classically conditioned,27 even by family interaction. Classic conditioning, as described by Pavlov, involves linking a neutral food or unconditioned stimulus (sound of a bell) with a conditioned stimulus (food) that elicits a conditioned response (salivation). After several trials, the unconditioned stimulus is able to produce the conditioned response. By contrast, operant conditioning involves the development of a desired response through motivation and reinforcement. Playing basketball is an example; accuracy improves through practice, and the correct behavior is reinforced by the reward of scoring a basket. Consider the following case.

In this case, the parent focused on the abdominal discomfort as an illness that required absence from school rather than as a physiologic response to a distressing situation. The child then avoided the feared situation. Repetition of the feared situation not only may lead to a conditionally enhanced psychophysiologic symptom response, but also may alter the child’s perception of the symptoms as illness, thereby leading to health care–seeking behaviors later in life (illness modeling).28 For example, in two studies,27,29 patients with IBS recalled more parental attention toward their illnesses than those with IBS who did not seek health care; they stayed home from school and saw physicians more often and received more gifts and privileges. Somatic responses to stressful situations may be reduced when the parent openly solicits and responds to the thoughts and feelings of the child, thus making these thoughts and feelings acceptable.

CULTURE AND FAMILY

Social and cultural belief systems modify how a patient experiences illness and interacts with the health care system.30 The meaning that an individual attributes to symptoms may be interpreted differently, even within the same ethnic group. Qualitative ethnographic studies conducted in New York City in the mid–twentieth century among white immigrants highlighted important cultural differences in pain behaviors.31,32 In these studies, first- and second-generation Jews and Italians were observed to embellish the description of pain by reporting more symptoms in more bodily locations and with more dysfunction and greater emotional expression. As noted by one Italian patient, “When I have a headache, I feel it’s very bad and it makes me irritable, tense, and short-tempered.” By contrast, the Irish might minimize the description of the pain: “It was a throbbing more than a pain,” and the “Old Americans” (Protestants) were stoic. These behaviors related to family attitudes and mores surrounding illness either reinforce or extinguish attention-drawing symptom reporting. As a further elaboration, whereas Italians were satisfied to hear that the pain was not a serious problem, the Jewish patients needed to understand the meaning of the pain and its future consequences, with the latter possibly relating to cultural influences on the importance of the acquisition of knowledge within the culture. Geographic differences are also noted with regard to worries and concerns about having IBD—for example, Southern European patients, such as Italian and Portuguese patients, report more and greater degrees of concern than their northern European counterparts.33

These cultural influences can shape health seeking and the respective roles of physicians and patients. From a global standpoint, 70% to 90% of all self-recognized illnesses are managed outside traditional medical facilities, often with self-help groups or religious cult practitioners providing a substantial portion of the care.34 Rural cultural groups, including Mexicans living on the American border, more often will go to a community healer (e.g., a curandero) first despite access to a standard medical facility.35 When given the option, the Romani (gypsies) will select only the top physicians (ganzos) to take care of a family member.36 Among whites, one third see practitioners of unconventional treatments (e.g., homeopathy, high colonic enemas, crystal healing) at a frequency that exceeds the number of primary care visits, and most do not inform their physicians of these treatments.37 Conversely, physicians may judge the appropriateness of patient behaviors on the basis of their own cultural biases and make efforts to show them the right way without first understanding the patient’s illness schema. Considering the hot-cold theory of illness practiced by some Puerto Ricans, if a clinician prescribes a hot medicine (not related to temperature) for a hot illness, the patient might not take that medicine. From a diagnostic standpoint, health care providers in the rural south need to be familiar with root working, a form of voodoo magic practiced by some rural African Americans.38 Acknowledging and addressing the patient’s beliefs can be therapeutic for the patient.

Psychosocial factors that relate to illness can be culturally determined and affect clinical management. In China, communicating psychological distress is stigmatizing,34 so when a person is in distress, reporting physical symptoms (somatization) is more acceptable,39 whereas in Southern Europe, emotional expression is not only assumed but also is a reinforcer of family support.32 In some nonliterate societies, individuals freely describe hallucinations that are fully accepted by others in the community.31 In fact, the meaning of the hallucinations, not their presence, is the focus of interest, particularly when reported by those in a position of power. Conversely, in Western societies, in which the emphasis is on rationality and control, hallucinations are viewed as stigmatizing, a manifestation of psychosis until proved otherwise.

PSYCHOSOCIAL ENVIRONMENT

LIFE STRESS AND ABUSE

Unresolved life stress, such as the loss of a parent, an abortion, a major personal catastrophic event or its anniversary, or daily life stresses (including having a chronic illness), may influence an individual’s illness in several ways, including the following: (1) producing psychophysiologic effects (e.g., changes in motility, blood flow, body fluid secretion, or bodily sensations, thereby exacerbating symptoms); (2) increasing one’s vigilance toward symptoms; and (3) leading to maladaptive coping and greater illness behaviors and health care seeking.13,40 Despite numerous methodologic limitations in studying the relationship of such psychosocial factors to illness, disease, and their outcomes, such factors clearly can exacerbate functional GI disorders14 and symptoms of certain structural disorders, such as IBD.41 Although the scientific evidence that such factors are causative in the development of pathologic diseases is compelling, based on retrospective studies and psychoimmunologic mechanisms, this conclusion is not fully established. Nevertheless, the negative impact of stressful life events on a person’s psychological state and illness behaviors requires the physician to address them in the daily care of all patients.

A history of physical or sexual abuse strongly influences the severity of the symptoms and clinical outcome.42 When compared with patients without a history of abuse, patients with a history of abuse who are seen in a referral gastroenterology practice reported 70% more severe pain (P < 0.0001) and 40% greater psychological distress (P < 0.0001), spent over 2.5 times more days in bed in the previous three months (11.9 vs. 4.5 days, P < 0.0007), had almost twice as poor daily function (P < 0.0001), saw physicians more often (8.7 vs. 6.7 visits over six months, P < 0.03), and even underwent more surgical procedures (4.9 vs. 3.8 procedures, P < 0.04) unrelated to the GI diagnosis.43 Life stress and abuse history have physiologic and behavioral effects that amplify the severity of the condition.

Several possible mechanisms help explain the relationship between a history of abuse and poor outcome.25 These mechanisms include the following: (1) susceptibility to developing psychological conditions that increase the perception of visceral signals or its noxiousness (central hypervigilance and somatization); (2) development of psychophysiologic (e.g., autonomic, humoral, immunologic) responses that alter intestinal motor or sensory function or promote inflammation; (3) development of peripheral or central sensitization from increased motility or physical trauma (visceral hyperalgesia or allodynia); (4) an abnormal appraisal of and behavioral response to physical sensations of perceived threat (response bias); and (5) development of maladaptive coping styles that lead to increased illness behavior and health care seeking (e.g., catastrophizing). Physiologically, in patients with IBS and a history of abuse, rectal distention produces more pain reporting with greater activation of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex44 compared with patients with IBS and no history of abuse; the pain and activation of the brain subside after treatment (see later).45

PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTORS

As shown in Figure 21-2, along with life stress and abuse, a mix of concurrent psychosocial factors can influence GI physiology and susceptibility to developing a pathologic condition and its symptomatic and behavioral expression, all of which affect the outcome. The psychological factors relate to long-standing (also called trait) features (e.g., personality and psychiatric diagnosis) and more modifiable state features (e.g., psychological distress and mood). The latter features are amenable to psychological and psychopharmacologic interventions. In addition, coping style and social support provide modulating (buffering) effects.

Personality

Are there specific personalities associated with GI disorders? During the psychoanalytically dominated era of psychosomatic medicine (1920 to 1955), certain psychological conflicts were believed to underlie development of personalities that expressed specific psychosomatic diseases (e.g., asthma, ulcerative colitis, essential hypertension, duodenal ulcer).46 In the biologically predisposed host, disease would develop when environmental stress was sufficient to activate the psychological conflict. The idea that personality features specifically relate to causation of medical disease (albeit in a biologically predisposed host), however, is too simplistic. Currently, investigators view personality and other psychological traits as enablers or modulators of illness, along with other contributing factors such as life stress, social environment, and coping.

Psychiatric Diagnosis

The co-occurrence of a psychiatric diagnosis in patients with a medical disorder (comorbidity) is common, and the psychiatric diagnosis aggravates the clinical presentation and outcome of the medical disorder. The most common psychiatric diagnoses seen among patients with chronic GI disorders are depression (including dysthymia) and anxiety (including panic attacks), and these psychiatric disorders are often amenable to psychopharmacotherapeutic or psychological treatment.14

When psychiatric disorders and personality traits adversely affect an individual’s experience and behavior to the point of interfering with interactions involving family, social peers, and physicians, these disorders and traits must be attended to. These conditions can include the following: somatization disorder, characterized by a fixed pattern of experiencing and reporting numerous physical complaints beginning early in life; factitious disorder, or possibly Munchausen’s syndrome, in which a patient surreptitiously simulates illness (e.g., ingesting laxatives, causing GI bleeding, feigning symptoms of medical illness) to obtain certain effects (e.g., to receive narcotics or operations and procedures); and borderline personality disorder, in which the individual demonstrates unstable and intense (e.g., overly dependent) interpersonal relationships, experiences marked shifts in mood, and exhibits impulsive (e.g., suicidal, self-mutilating, sexual) behaviors.47 It is important for the physician to recognize these patterns to avoid maladaptive interactions, to maintain clear boundaries of medical care (e.g., not to overdo studies based on the patient’s requests) and, when necessary, to refer the patient to a mental health professional skilled in the care of patients with these conditions.

Psychological Distress

Even for a previously healthy person, having an illness can cause psychological distress, which is understood as transient and modifiable symptoms of anxiety, depression, and other mood disturbances. Psychological distress also affects the medical disorder and its outcome; it lowers the pain threshold48 and influences health care seeking for patients with a functional bowel disturbance and those with a structural disease.14 Psychosocial difficulties may not be recognized by the patient, even if evident to the health care provider. When patients with IBS who seek health care are compared with those who do not see a physician, the former group report greater psychological difficulties but also may deny the role of these difficulties in their illnesses.49 This pattern may develop early in life. The young child, Johnny, described earlier, who was becoming conditioned to report somatic symptoms when distressed, may not recognize or communicate the association of symptoms with the stressful antecedents, because these antecedents were not acknowledged or attended to within the family. The ability to become consciously aware of one’s own feelings is believed to be a cognitive skill that goes through a developmental process similar to that which Piaget described for other cognitive functions.50 This development, however, may be suppressed in oppressive family environments.

Alexithymia (from the Greek, “absence of words for emotions”) describes patients who have chronic difficulties recognizing and verbalizing emotions. Alexithymia is believed to develop in response to early traumatic experiences such as abuse, severe childhood illness, or deprivation. Patients with alexithymia may express strong emotions, such as anger or sadness, in relation to their illnesses, but they know little about the psychological basis for these feelings and cannot link them with past experience or current illness.51 This lack of understanding limits their ability to regulate emotions, use coping strategies effectively, and adjust to their chronic condition. Their tendency to communicate emotional distress through somatic symptoms and illness behavior, rather than verbally, appears to be associated with more frequent physician visits and a poorer prognosis.52 Difficulties in awareness of one’s own emotional levels has been reported in the practice of gastroenterology in patients with functional as well as structural GI disorders.53,54

COPING AND SOCIAL SUPPORT

Coping and social support modulate (by buffering [turning down] or enabling [turning up and amplifying]) the effects of life stress, abuse, and morbid psychological factors on the illness and its outcome. Coping has been defined as “efforts, both action-oriented and intrapsychic, to manage (i.e., master, tolerate, minimize) environmental and internal demands and conflicts that tax or exceed a person’s resources.”55 In general, emotion-based coping (e.g., denial or distraction), although possibly adaptive for acute overwhelming stresses, is not effective for chronic stressors, whereas problem-based coping strategies (e.g., seeking social support or reappraising the stressor) involves efforts to change one’s response to the stressor and is more effective for chronic illness. Patients with Crohn’s disease who do not engage in emotion-based coping, such as social diversion or distraction, are less likely to relapse.56 For GI diagnoses of all types, we have found57 that a maladaptive emotional coping style, specifically catastrophizing, along with the perceived inability to decrease symptoms, led to higher pain scores, more physician visits, and poorer functioning over the subsequent one-year period. Catastrophizing is also associated with more difficult interpersonal relationships,58 predicts postoperative pain,59 and contributes to greater worry and suffering in patients with IBS.60 Therefore, efforts made through psychological treatments to improve a person’s appraisal of the stress of illness and ability to manage symptoms is likely to improve health status and outcome.14

Social support through family, religious, and community organizations and other social networks can have similar benefits in reducing the impact of stressors on physical and mental illness, thereby improving ability to cope with the illness.61 Using IBD as an example, patients who have satisfactory social support are able to reduce the psychological distress related to their conditions,62 and good social support improves health-related quality of life after surgery.63

BRAIN-GUT AXIS

The combined functioning of GI motor, GI sensory, and CNS activity is considered the brain-gut axis, and dysregulation of this system’s homeostasis explains altered GI functioning, GI symptoms, and functional GI disorders to a great extent. The brain-gut axis is a bidirectional and integrated system in which thoughts, feelings, memories, and environmental influences can lead to neurotransmitter release that affects sensory, motor, endocrine, autonomic, immune, and inflammatory function.64,65 Conversely, altered functioning or disease of the GI tract can reciprocally affect mental functioning. In effect, the brain-gut axis is the neuroanatomic and neurophysiologic substrate of the clinical application of the biopsychosocial model.

STRESS AND GASTROINTESTINAL FUNCTION

An observational relationship between stress and GI function has been part of the writings of poets and philosophers for centuries.66 Stress is difficult to understand and study; no definition is entirely satisfactory. The human organism functions in a constantly changing environment. Any influence on one’s steady state that requires adjustment or adaptation can be considered stress. The term is nonspecific and encompasses the stimulus and its effects. The stimulus can be a biologic event such as infection, a social event such as a change of residence, or even a disturbing thought. Stress can be desirable or undesirable. Some stimuli, such as pain, sex, or threat of injury, often elicit a predictable response in animals and humans. By contrast, life events and many other psychological processes have more varied effects. For example, a change of jobs may be of little concern to one person but a crisis to another, who perceives it as a personal failure. A stimulus may produce a variety of responses in different persons or in the same person at different times. The effect may be nonobservable, a psychological response (anxiety, depression), a physiologic change (diarrhea, diaphoresis), the onset of disease (asthma, colitis), or any combination of these. A person’s interpretation of events as stressful or not and his or her response to stress depend on prior experience, attitudes, coping mechanisms, personality, culture, and biological factors, including susceptibility to disease. The nonspecific nature of the term stress precludes its use as a distinct variable for research.

Healthy subjects commonly have abdominal discomfort or change in bowel function when they are upset or distressed,67 a fact usually taken into account by clinicians who manage patients. Clinical reports and psychophysiologic studies in animals and humans support these observations. Cannon noted a cessation in bowel activity in cats when reacting to a growling dog.68 Pavlov first reported that psychic factors affect gastric acid secretion via the vagus nerve in dogs.69 In humans, Beaumont,70 Wolf and Wolff,71 and Engel and colleagues72 observed changes in the color of the mucosa and secretory activity of a gastric pouch or fistula in response to psychological and physical stimuli. Gastric hyperemia and increased motility and secretion were linked to feelings of anger, intense pleasure, or aggressive behavior toward others. Conversely, mucosal pallor and decreased secretion and motor activity accompanied fear or depression, states of withdrawal (i.e., giving up behavior), or disengagement from others.

Subsequently, studies were reported that showed the effects of experimental stress on physiologic functioning in almost all segments of the GI tract. Complicated cognitive tasks produce the following: (1) high-amplitude, high-velocity esophageal contractions73; (2) increased chymotrypsin output from the pancreas74; (3) reduction of phase II intestinal motor activity75; and (4) prolongation of phase III activity of the migrating myoelectric complex (MMC)74 in the small intestine (see Chapters 42, 56, and 97). Experimentally induced anger increases motor and spike potential activity in the colon, and this change is greater in patients with functional bowel disorders (see Chapter 98).76 In one study,48 psychological stress was more likely than physical stress to produce propagated contractions in the colon, which presumably would be associated with the development of diarrhea.77 Physical or psychological stress also can lower the pain threshold, particularly in patients with IBS.

ROLE OF NEUROTRANSMITTERS

The richly innervated nerve plexuses and neuroendocrine associations of the CNS and ENS provide the hard wiring for reciprocal activity between brain and gut. The mediation of these activities involves neurotransmitters and neuropeptides found in the CNS and intestine, including corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) and its congeners, substance P, nitric oxide (NO), cholecystokinin (CCK), and enkephalin. Depending on their location, these substances have integrated activities on GI function and human behavior. For example, the stress hormone CRF has central stress modulatory and peripheral gut physiologic effects. It produces gastric stasis and an increase in the colonic transit rate in response to psychologically aversive stimuli78 and can increase visceral hypersensitivity79 and alter immune functioning.64 Thus, CRF appears to be active in stress-induced exacerbations of IBS80 and in cyclic vomiting syndrome (see Chapters 14 and 118).81

REGULATION OF VISCERAL PAIN

An important example of brain-gut axis function relates to the regulation of visceral pain.

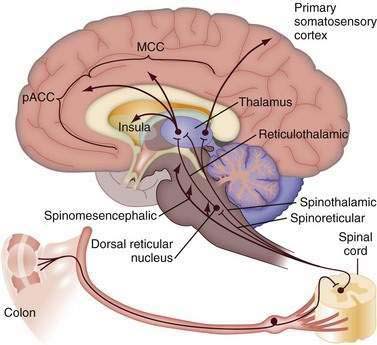

Transmission to the Central Nervous System

Figure 21-3 shows ascending afferent pathways from the colon. After visceral stimulation by colonic dilatation, first-order visceral neurons are stimulated and then project to the spinal cord, where they synapse with second-order neurons and ascend to the thalamus and midbrain (see Chapter 11). Of the several supraspinal pathways (spinothalamic, spinoreticular, and spinomesencephalic), the spinothalamic tract shown on the right in Figure 21-3 terminates in the medial thalamus and projects as a third-order neuron to the primary somatosensory cortex. This pathway is important for sensory discrimination and localization of visceral and somatic stimuli (i.e., determining the location and intensity of pain). The spinoreticular tract (middle pathway) conducts sensory information from the spinal cord to the brainstem (reticular formation). Notably, this region is involved mainly in the affective and motivational properties of visceral stimulation—that is, the emotional component of pain. The reticulothalamic tract projects from the reticular formation to the medial thalamus on the left and then to the cingulate cortex. This is shown in Figure 21-3 as divided into subcomponents, including the perigenual anterior cingulate cortex (pACC), MCC, and insula, which are involved with the processing of noxious visceral and somatic information. This multicomponent integration of nociceptive information, dispersed to the somatotypic-intensity area (lateral sensory cortex) and to the emotional or motivational-affective area of the medial cortex, explains variability in the experience and reporting of pain.

This conceptual scheme of pain modulation through sensory and motivational-affective components has been supported through positron emission tomography (PET) imaging using radiolabeled oxygen.82 In healthy subjects who immersed their hands in hot (47°C) water, hypnotic suggestion could make the experience painful or pleasant. Notably, no differences were observed between the two groups in somatosensory cortical activation, but in hypnotized subjects who experienced the hand immersion as painful, the activation of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) was higher. Thus, the hypnotic suggestion differentiated the functioning of these two pain systems. The suggestion of unpleasantness is specifically encoded in the anterior midcingulate portion of the ACC, an area involved with negative perceptions of fear and unpleasantness; this is the area associated with functional pain syndromes (see later).

Amplification of Visceral Afferent Signals

The evidence is growing that visceral inflammation and injury can amplify ascending visceral pathways. An increase in the sensitivity of peripheral receptors or the excitability of spinal or higher CNS pain regulatory systems may produce hyperalgesia (increased pain response to a noxious signal), allodynia (increased pain response to non-noxious or regulatory signals), or chronic pain.65 Chronic pain results from prior episodes of recurrent pain events that become generalized to a persistent symptom presentation. The CNS response (hyperalgesia) to peripheral injury may be reduced by a preemptive reduction in the afferent input to the spinal cord and CNS (e.g., by analgesia or a local anesthetic).83

Visceral hypersensitivity is well demonstrated in immature (i.e., neonate) animals, in which inflammation or injury to nerve fibers can alter the function and structure of peripheral neurons84 and thereby result in a greater pain response to visceral distention when the animals mature and become adults.85 In humans, repetitive balloon inflations can later lead to an enhanced pain response to rectal distention (visceral hypersensitivity),86 as shown by the observation that patients with IBS have a greater degree of and more prolonged pain after a colonoscopy.

Perhaps the best clinical model for the effects of inflammation on visceral hypersensitivity is the postinfection IBS model (PI-IBS).87 PI-IBS results from an inflammation-induced altered mucosal immune response that sensitizes visceral afferent nerves88 in a setting of emotional distress.89 The CNS amplification of the visceral signals that occur in psychologically distressed persons probably raises the afferent signals to conscious awareness and an enhanced perception of symptoms.90 In multivariate analyses, both enterochromaffin cell hyperplasia (with increased production of 5-HT) and depression are equally important predictors of the development of PI-IBS (risk ratio, 3.8 and 3.2, respectively).91 These data support the contention that for PI-IBS to become clinically expressed, evidence of brain-gut dysfunction must exist, with visceral sensitization and high levels of psychological distress. Some of the effect may result from stress-mediated activation of mast cells, which in turn leads to neural sensitization.92

Descending Modulation

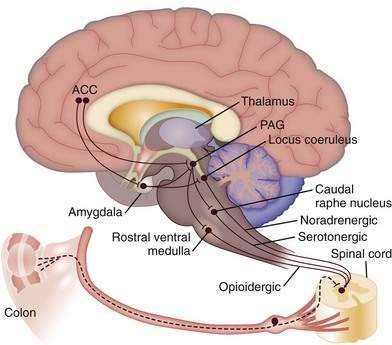

Figure 21-4 shows the central descending inhibitory system that is believed to originate in the pACC, an area rich in opioids.93 Activation of this region from visceral afferent activity may down-regulate afferent signals via descending corticofugal inhibitory pathways. Descending connections from the ACC and the amygdala to pontomedullary networks, including the periaqueductal gray (PAG), rostral ventral medulla (RVM), and raphe nuclei, activate inhibitory pathways via opioidergic, serotonergic, and noradrenergic systems94 to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. The dorsal horn acts like a gate to increase or decrease the projection of afferent impulses arising from peripheral nociceptive sites to the CNS (see Chapter 11). Psychological treatments and antidepressants are thought to activate these descending pathways.

Psychological Distress and Its Influence on Central Amplification

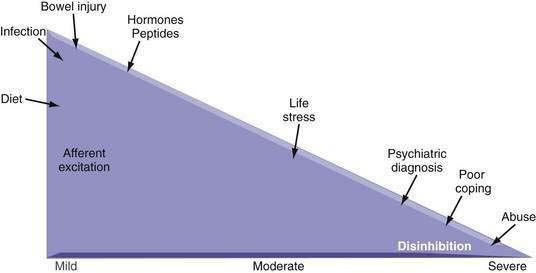

Psychological disturbances may amplify the pain experience (i.e., CNS sensitization).95 Whereas peripheral sensitization may influence the onset and short-term continuation of pain, the CNS appears involved in the predisposition and perpetuation of pain, thereby leading to a more severe chronic pain condition. Empirical data have supported the hypothesis that a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis, major life stress, history of sexual or physical abuse, poor social support, and maladaptive coping are associated with more severe and more chronic abdominal pain and a poorer health outcome.43,96 Figure 21-5 demonstrates this association for functional and structural GI disorders. For most patients with mild-to-moderate symptoms, environmental and bowel-related factors (e.g., intestinal infection, inflammation, or injury, diet, hormonal factors) can lead to afferent excitation and up-regulation of afferent neuronal activity. Patients with moderate to severe symptoms also have impaired central modulation of pain as a result of various psychosocial factors, with decreased central inhibitory effects on afferent signals at the level of the spinal cord (disinhibition). Knowing the severity of the disorder and the purported site of action (i.e., intestine, brain, or both) can help when choosing an approach to treatment. When peripheral influences on severity predominate, medications, surgery, or other modalities that act on the intestine are primary treatment considerations. As pain symptoms become more severe, however, behavioral and psychopharmacologic treatments need to be added.

Cingulate Mediation of Psychosocial Distress and Pain

The relationship between psychosocial distress and painful GI symptoms appears to be mediated through impairment in the ability of the cingulate cortex to process incoming visceral signals. The ACC, which is involved in the motivational and affective components of the limbic, or medial, pain system, is dysfunctional in patients with IBS and other chronic painful conditions like fibromyalgia97,98 and may be similarly involved with structural diagnoses, such as IBD-IBS.3 The pACC, an area rich in opioids associated with emotional encoding and down-regulation of pain, and the dorsal ACC (also called the rostral or anterior MCC), may be activated to varying degrees in response to painful stimuli. The dorsal ACC, along with the amygdala, is associated with unpleasantness, fear, and an increase in responses to motor pain.99 When PET and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) are used to evaluate the response of the ACC to rectal distention or to the anticipation of distension, patients with IBS display preferential activation of the MCC and less activation of the pACC than controls.97,100,101 In IBS, activation of the descending inhibitory pain pathway that originates in the opioid-rich pACC might be supplanted by activation of the MCC, the area associated with fear and unpleasantness. Similar findings occur in patients with somatization102 and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).103

A history of abuse amplifies GI pain via central dysregulation. A history of abuse in a patient with IBS leads to greater dorsal ACC activation and reporting of pain with rectal distention than either condition alone.44 This finding supports observational studies that patients with GI disorders of any type who have a history of abuse report more pain and have poorer health behaviors than those with only the GI diagnosis.43 With clinical recovery, CNS activity appears to return to normal (i.e., reduced MCC and increased insular activation).45,104

These observations have been supported by a study of the Gulf War and related health issues.105 The report portrays a strong relationship between the deployment of soldiers to a war zone with traumatic exposure to injury, mutilation, or dead bodies and the ensuing development of medical and psychological symptoms and syndromes. In fact, clusters of several medical symptoms were noted, such as those termed Gulf War syndrome, which includes IBS, chronic fatigue, and chemical sensitivity syndrome, in addition to PTSD and cognitive impairments.

Therefore, the psychological effects of abuse or wartime exposure may produce disruption in central pain modulation systems and in brain circuits at the interface of emotion and pain.44 This change leads to a lowering of sensation thresholds, with a loss of the brain’s ability to filter bodily sensations. The result is an increase in physical and psychological symptoms and more intense pain and syndromes (e.g., IBS, fibromyalgia, headache, widespread body pain), a condition that has been variably described as somatization, comorbidity, or just extraintestinal functional GI symptoms.105 The data suggest that psychological and antidepressant treatments are potentially beneficial for more severe forms of chronic pain, in which CNS contributions are thought to be preeminent.

EFFECTS OF STRESS ON IMMUNE FUNCTION AND DISEASE SUSCEPTIBILITY

Stressful experiences can also affect peripheral immune function and ultimately susceptibility to disease; conversely, peripheral immune and inflammatory mediators can affect psychological functioning. The discipline of psychoneuroimmunology began in the 1970s, when alterations of immune function were first documented in astronauts after splashdown.106 Later, in vitro experiments showed effects of acute stress on lymphoproliferative activity, interferon production, and DNA repair.107,108 Clinical studies have shown that chronically distressed persons (e.g., long-term caregivers of spouses with dementia) have impaired cellular immunity and higher frequencies of depression and respiratory infections compared with matched controls,109 and persons under psychological distress have a higher frequency of respiratory infections after intranasal virus inoculation.110 In patients with multiple myeloma, stress management treatment has been associated with an increased number of natural killer (NK) cells, a significantly lower mortality rate after six years, and a trend toward fewer tumor recurrences as compared with a control group of patients who did not undergo stress management treatment.111

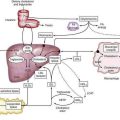

The principal mediators of the stress-immune response include CRF and the locus-coeruleus-norepinephrine (LC-NE) systems in the CNS. These systems are influenced by numerous positive and negative feedback systems that allow behavioral and peripheral adaptations to stress.112 The peripheral limb of the CRF system is the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, a negative feedback system involved in psychoneuroimmunologic regulation. In the HPA system, inflammatory cytokines, primarily tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1, and IL-6, liberated during inflammation, stimulate the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus to secrete CRF. CRF stimulates the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH; corticotropin), which, in turn, stimulates the adrenal glands to release glucocorticoids. Finally, the glucocorticoids suppress inflammation and cytokine production, thereby completing the negative feedback loop.113

CRF is recognized to be important via central and peripheral pathways in stress-related modulation of GI motor and sensory function114 and may be involved in the generation or maintenance of pain-related symptoms sensitive to modulation by psychological stress.115 Furthermore, disruptions in the HPA system can lead to behavioral and systemic disorders as a result of increased (e.g., Cushing’s syndrome, depression, susceptibility to infection) or decreased (e.g., adrenal insufficiency, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic fatigue syndrome, PTSD) HPA axis reactivity.112 Inflammatory GI disorders (e.g., IBD) also may be affected through this stress-mediated system.41

The clinical evidence to support a role for stress in activation of human IBD, or other structural disorders, is limited because of methodologic limitations of available studies. The evidence from clinical observational data, however, is compelling. For example, in one study of 62 patients with ulcerative colitis who were followed prospectively for more than five years,116 27 experienced an exacerbation, and the psychosocial predictors of disease exacerbation were assessed. Patients who scored high on a measure of long-term perceived stress had an increased actuarial risk of an exacerbation of ulcerative colitis (hazard ratio = 2.8; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1 to 7.2), and exacerbation was not associated with short-term perceived stress or with the extent, duration, or severity of the colitis.

CYTOKINES AND THE BRAIN

Stress might have proinflammatory effects, but intestinal inflammation also may affect behavior reciprocally via activation of cytokines. Many behavioral features (e.g., fever, fatigue, anorexia, depression) of chronic inflammatory diseases may result from the central effects of peripherally activated inflammatory cytokines.117,118 Sickness behavior refers to the coordinated set of behavioral changes that develop in sick persons during the course of IBD, cancer, infection, or other catabolic disorders associated with cytokine activation. At the molecular level, these changes result from the effects of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1 and TNF-α, in the brain. Peripherally released cytokines act on the brain via a fast transmission pathway, which involves primary afferent nerves that innervate the site of inflammation, and a slow transmission pathway, which involves cytokines that originate from the choroid plexus and circumventricular organs and diffuse into the brain parenchyma. At the behavioral level, sickness behavior appears to be the expression of a central motivational state that reorganizes the organism’s priorities to cope with infectious pathogens.

OUTCOME

The severity or activity of GI disease is not sufficient to explain a patient’s health status and its consequences fully. Early life conditioning and current psychological difficulties also influence a variety of outcome measures, including symptoms, health care seeking, quality of life—a global measure of the patient’s perceptions, illness experience, and functional status that incorporates social, cultural, psychological, and disease-related factors—and health care costs, in some cases more than disease-related factors.14 When the effects of early life conditioning on health care visits and costs were assessed, the children of parents diagnosed with IBS had significantly more ambulatory care visits for all medical (12.3 vs. 9.8; P < 0.0001) and GI symptoms (0.35 vs. 0.18; P < 0.0001), and outpatient health care costs over three years were also higher ($1979 vs. $1546; P < 0.0001) than those for a comparison group of children whose parents did not have IBS.119 Presumably, the parents with IBS were vigilant, and responded more often, to the symptoms (GI or non-GI) of their children and more readily sought health care for them.

In adults, psychosocial factors affect symptom reporting and health care seeking. In one survey of 997 subjects with IBD who belonged to the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America,120 the number of physician visits was related to psychosocial factors (e.g., psychological distress, perceived well-being, and physical functioning), whereas the severity of symptoms was not found to predict this outcome. Other important psychosocial predictors of poorer health outcome (e.g., symptom severity, phone calls, doctor visits, daily function, and health-related quality of life) for functional or structural disorders include a history of sexual or physical abuse,43 maladaptive illness beliefs,121,122 ineffective coping strategies (e.g., catastrophizing), and perceived inability to decrease symptoms.57

CLINICAL APPLICATIONS

The data relating to the scientific basis for an association between psychosocial factors and GI illness and disease require that the physician obtain, organize, and integrate psychosocial information to achieve optimal care. The recommendations offered here are particularly useful for patients who have chronic illness or major psychosocial difficulties. More comprehensive discussions of techniques for obtaining and analyzing the data and of the interview process are found elsewhere.47,123,124

HISTORY

The medical history should be obtained through a patient-centered nondirective interview during which the patient is encouraged to tell the story in his or her own way, so that the events contributing to the illness unfold naturally.125 Open-ended questions are used initially to generate hypotheses, and additional information is obtained with facilitating expressions—“Yes?,” “Can you tell me more?” Repeating the patient’s previous statements, head nodding, or even silent pauses with an expectant look can facilitate history taking. Avoid closed-ended (yes-no) questions at first, although they can be used later to characterize the symptoms further. Never use multiple-choice or leading questions, because the patient’s desire to comply may bias the responses.

The historical information should be obtained from the perspective of the patient’s understanding of the illness. Important questions to ask include the following126:

EVALUATING THE DATA

The physician must assess the relative influences of the biological, psychological, and social dimensions on the illness. Determining whether psychosocial or biological processes are operative in an illness is unnecessary and possibly countertherapeutic. Usually, both are important, and treatment is based on determining which is identifiable and remediable. A negative medical evaluation is not sufficient for making a psychosocial diagnosis. Table 21-1 lists several questions to consider in the assessment and evaluation of the patient.47

Table 21-1 Questions to Consider in the Clinical Evaluation of the Patient

DIAGNOSTIC DECISION MAKING

The case of Ms. L, the patient with persistent and unexplained abdominal pain, is an example familiar to the gastroenterologist. The urge to work up a patient with chronic abdominal pain must be tempered by the evidence that an adequate initial evaluation considerably reduces the likelihood of finding an overlooked cause later. Here, the clinical approach is not medical diagnosis, but psychosocial assessment and treatment of the chronic pain.6,126 Factors associated with or exacerbating chronic pain symptoms include the following: (1) a recent disruption in the family or social environment (e.g., child leaving home, argument); (2) major loss or anniversaries of losses (e.g., death of a family member or friend, hysterectomy, interference with the outcome of pregnancy); (3) history of sexual or physical abuse; (4) onset or worsening of depression or other psychiatric diagnosis; and (5) a hidden agenda (e.g., narcotic-seeking behavior, laxative abuse, pending litigation, disability). Although psychiatric consultation and treatment may be needed, it is important that the physician should continue to be involved in the patient’s care and be vigilant about the development of new findings.

TREATMENT APPROACH

ESTABLISHING A THERAPEUTIC RELATIONSHIP

The physician establishes a therapeutic relationship when he or she does the following: (1) elicits and validates the patient’s beliefs, concerns, and expectations; (2) offers empathy when needed; (3) clarifies the patient’s misunderstandings; (4) provides education; and (5) negotiates the plan of treatment with the patient.125 This strategy must be individualized, because patients vary in the degree of negotiation and participation they require. The physician must be nonjudgmental, show interest in the patient’s well-being, and be prepared to exercise effective communication skills.123

Reinforcing Healthy Behaviors

Sometimes, complaints of physical distress are a maladaptive effort to communicate emotional distress or to receive attention.127 The physician may unwittingly reinforce this behavior in several ways: (1) by paying a great deal of attention to the patient’s complaints, to the exclusion of other aspects; (2) by acting on each complaint by ordering diagnostic studies or giving a prescriptive medication; or (3) by assuming total responsibility for the patient’s well-being. The patient learns to keep the physician’s interest by reporting symptoms rather than by trying to improve, perpetuating the cycle of symptom recitation and passive interaction.

PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT

Psychopharmacologic or psychotropic agents act on neurotransmitter receptors in the brain-gut regulatory pathways that target serotonergic, dopaminergic, opioidergic, and noradrenergic receptor sites and produce various effects in the following ways: (1) by reducing visceral afferent signaling from painful GI conditions; (2) by treating GI pain by facilitating central down-regulating pathways; (3) depending on the agent, by modifying diarrhea or constipation; (4) by reducing anxiety, depression, nausea, and loss of appetite; and (5) in higher doses, by treating major depression or other psychiatric disorders.128

The tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) in relatively low doses can reduce chronic pain129,130 through peripheral and central mechanisms, including activation of corticofugal pain inhibitory pathways by endorphins. They can also treat major and secondary depressive symptoms when used in full antidepressant doses. They may have antihistaminic and anticholinergic effects that could lead to nonadherence.

The serotonin-norepinephrine receptor inhibitors (SNRIs) are a more recently introduced class of antidepressants that appear to be particularly helpful for the treatment of painful conditions. The presence of any syndromes associated with deterioration in daily function (e.g., inability to work) or of vegetative symptoms (e.g., poor appetite, weight loss, sleep disturbance, decreased energy and libido) subserved by central brain monoamine function, are reasonable indications for a therapeutic trial. They should be considered even if the patient denies feelings of sadness (masked depression). Treatment should be increased to full therapeutic levels over two to three weeks and maintained for six to nine months. Poor clinical responses may be the result of relatively low doses.131

Antipsychotic drugs, or neuroleptics, include the phenothiazines (e.g., chlorpromazine), butyrophenones (e.g., haloperidol), and newer classes of safer antipsychotic agents (e.g., quetiapine, olanzapine) and are used primarily for treating disturbances of thought, perception, and behavior in psychotic patients. Increasingly, they are being used in lower doses to promote sleep, achieve anxiolytic and antidepressant effects, and augment the analgesic effects of antidepressants; they may have a role in pain management.132

Opiates have little role in treating patients with chronic pain or psychosocial disturbance because of their potential for abuse, dependency, and narcotic bowel syndrome (see Chapters 11 and 120).15

PSYCHOTHERAPY AND BEHAVIORAL TREATMENTS

The need for adjunctive care by a psychiatrist, psychologist, or other mental health professional should be determined through an assessment of the personal, social, and economic hardship of the illness, rather than identification of a specific psychiatric diagnosis per se. Referral is based on the likelihood of improved function, mood, or coping style following the intervention. The patient must see psychological care as relevant to personal needs, rather than “to prove I’m not crazy.” Psychological treatments for GI disorders have been reviewed elsewhere.14

PHYSICIAN-RELATED ISSUES

Patients’ psychosocial difficulties may affect the physician’s attitudes and behaviors7 and, if unrecognized, may adversely affect the patient’s care. Physicians are uncomfortable making decisions in the face of diagnostic uncertainty,133 because the assumption is that more knowledge will make the illness more treatable. Nonetheless, many clinical treatments are undertaken for symptoms or psychosocial concerns that are not based on a specific diagnosis, particularly for patients with unexplained complaints who demand a diagnosis or for those who are thought to be litigious. Here, the physician risks overdoing the diagnostic evaluation or instituting unneeded or harmful treatments in such patients (sometimes called furor medicus).134 Alternatively, the physician may not believe that the complaints are legitimate and may then exhibit behaviors (e.g., referring the patient to a psychiatrist) that the patient will recognize as a rejection.

Creed F, Levy R, Bradley L, et al. Psychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, et al, editors. Rome III: The functional gastrointestinal disorders. 3rd ed. McLean, Va: Degnon Associates; 2006:295-368. (Ref 14.)

Drossman DA. Presidential Address: Gastrointestinal illness and biopsychosocial model. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:258-67. (Ref 16.)

Drossman DA. Brain imaging and its implications for studying centrally targeted treatments in IBS: A primer for gastroenterologists. Gut. 2005;54:569-73. (Ref 95.)

Drossman DA. Severe and refractory chronic abdominal pain: Treatment strategies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:978-82. (Ref 6.)

Drossman DA, Leserman J, Mitchell CM, et al. Health status and health care use in persons with inflammatory bowel disease: A national sample. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:1746-55. (Ref 120.)

Drossman DA, Ringel Y. Psychosocial factors in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. In: Sartor BR, Sandborn WJ, editors. Kirsner’s inflammatory bowel disease. 6th ed. London: WB Saunders; 2004:340-356. (Ref 41.)

Grover M, Drossman DA. Psychotropic agents in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:715-23. (Ref 128.)

Jones MP, Dilley JB, Drossman D, Crowell MD. Brain-gut connections in functional GI disorders: Anatomic and physiologic relationships. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18:91-103. (Ref 65.)

Kellow JE, Azpiroz F, Delvaux M, et al. Principles of applied neurogastroenterology: Physiology/motility-sensation. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, et al, editors. Rome III: The functional gastrointestinal disorders. 3rd ed. McLean, Va: Degnon Associates; 2006:89-160. (Ref 86.)

Leserman J, Drossman DA. Relationship of abuse history to functional gastrointestinal disorders and symptoms: Some possible mediating mechanisms. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007;8:331-43. (Ref 25.)

Levenstein S, Prantera C, Varvo V, et al. Stress and exacerbation in ulcerative colitis: A prospective study of patients enrolled in remission. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1213-20. (Ref 116.)

Mayeux R, Drossman DA, Basham KK, et al. Gulf war and health: Physiologic, psychologic, and psychosocial effects of deployment-related stress. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2008. (Ref 105.)

Naliboff BD, Derbyshire SWG, Munakata J, et al. Cerebral activation in irritable bowel syndrome patients and control subjects during rectosigmoid stimulation. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:365-75. (Ref 97.)

Ringel Y, Drossman DA, Leserman JL, et al. Effect of abuse history on pain reports and brain responses to aversive visceral stimulation: An FMRI study. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:396-404. (Ref 44.)

Spiller RC. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1662-71. (Ref 88.)

Wood JD, Grundy D, Al-Chaer ED, et al. Fundamentals of neurogastroenterology: Basic science. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, et al, editors. Rome III: The functional gastrointestinal disorders. 3rd ed. McLean, Va: Degnon Associates; 2006:31-87. (Ref 80.)

1. Reading A. Illness and disease. Med Clin North Am. 1977;61:703-6.

2. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129-36.

3. Grover M, Herfarth H, Drossman DA. The functional-organic dichotomy: Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease–irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:48-53.

4. Drossman DA, Functional GI. disorders: What’s in a name? Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1771-2.

5. Longstreth GF, Drossman DA. Severe irritable bowel and functional abdominal pain syndromes: Managing the patient and health care costs. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:397-400.

6. Drossman DA. Severe and refractory chronic abdominal pain: Treatment strategies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:978-82.

7. Drossman DA. Challenges in the physician-patient relationship: Feeling “drained.”. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1037-8.

8. Kroenke K, Mangelsdorff AD. Common symptoms in ambulatory care: Incidence, evaluation, therapy, and outcome. Am J Med. 1989;86:262-6.

9. Clouse RE, Mayer EA, Aziz Q, Drossman DA, et al. Functional abdominal pain syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1492-7.

10. Drossman DA. Functional abdominal pain syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:353-65.

11. Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, et al, editors. Rome III: The functional gastrointestinal disorders, 3rd ed, McLean, Va: Degnon Associates, 2006.

12. Russo MW, Gaynes BN, Drossman DA. A national survey of practice patterns of gastroenterologists with comparison to the past two decades. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;29:339-43.

13. Drossman DA, Creed FH, Olden KW, et al. Psychosocial aspects of the functional gastrointestinal disorders. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Talley NJ, et al, editors. Rome II. The functional gastrointestinal disorders: Diagnosis, pathophysiology and treatment. A Multinational Consensus. 2nd ed. McLean, Va: Degnon Associates; 2000:157-245.

14. Creed F, Levy R, Bradley L, et al. Psychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, et al, editors. Rome III: The functional gastrointestinal disorders. 3rd ed. McLean, Va: Degnon Associates; 2006:295-368.

15. Grunkemeier DMS, Cassara JE, Dalton CB, Drossman DA. The narcotic bowel syndrome: Clinical features, pathophysiology, and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1126-39.

16. Drossman DA. Presidential Address: Gastrointestinal illness and biopsychosocial model. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:258-67.

17. Lane RD, Waldstein SR, Chesney MA, et al. The rebirth of neuroscience in psychosomatic medicine. Part I: Historical context, methods and relevant basic science. Psychosom Med Psychosom Med. 2009;71:117-34.

18. Rasquin A, Di Lorenzo C, Forbes D, Guiraldes E, et al. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: Child/adolescent. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1527-37.

19. Drossman DA. The eating disorders. In: Wyngaarden JB, Smith LH, editors. Cecil textbook of medicine. 19th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1991:1158-1161.

20. Hill OW. Psychogenic vomiting. Gut. 1968;9:348-52.

21. Whitehead WE, Crowell MD, Schuster MM. Functional disorders of the anus and rectum. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 1990;1:74-84.

22. Leroi AM, Bernier C, Watier A, et al. Prevalence of sexual abuse among patients with functional disorders of the lower gastrointestinal tract. Int J Colorect Dis. 1995;10:200-6.

23. Bemporad JR, Kresch RA, Asnes R. Chronic neurotic encopresis as a paradigm of a multifactorial psychiatric disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1978;166:472-9.

24. Bellman M. Studies on encopresis. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1966;56:1-151.

25. Leserman J, Drossman DA. Relationship of abuse history to functional gastrointestinal disorders and symptoms: Some possible mediating mechanisms. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007;8:331-43.

26. Levy RL, Whitehead WE, Walker LS, et al. Increased somatic complaints and health-care utilization in children: Effects of parent IBS status and parent response to gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2442-51.

27. Whitehead WE, Winget C, Fedoravicius AS, et al. Learned illness behavior in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer. Dig Dis Sci. 1982;27:202-8.

28. Levy RL, Whitehead WE, Von Korff MR, Feld AD. Intergenerational transmission of gastrointestinal illness behavior. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:451-6.

29. Lowman BC, Drossman DA, Cramer EM, McKee DC. Recollection of childhood events in adults with irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1987;9:324-30.

30. Drossman DA, Weinland SR. Sociocultural factors in medicine and gastrointestinal research. Euro J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:593-5.

31. Zola IK. Culture and symptoms—an analysis of patients’ presenting complaints. Am Sociolog Rev. 1966;31:615-30.

32. Zborowski M. Cultural components in responses to pain. J Social Issues. 1952;8:16-30.

33. Levenstein S, Li Z, Almer S, et al. Cross-cultural variation in disease-related concerns among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1822-30.

34. Kleinman A, Eisenberg L, Good B. Culture, illness and care. Clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88:251.

35. Zuckerman MJ, Guerra LG, Drossman DA, et al. Health care seeking behaviors related to bowel complaints: Hispanics versus non-Hispanic whites. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:77-82.

36. Thomas JD. Gypsies and American medical care. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:842-5.

37. Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, et al. Unconventional medicine in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:246-52.

38. Tinling DC. Voodoo, root work, and medicine. Psychosom Med. 1967;29:483-90.

39. Hsu LK, Folstein MF. Somatoform disorders in Caucasian and Chinese Americans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185:382-7.

40. Drossman DA, Creed FH, Olden KW, et al. Psychosocial aspects of the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut. 1999;45(Suppl II):II25-30.

41. Drossman DA, Ringel Y. Psychosocial factors in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. In: Sartor BR, Sandborn WJ, editors. Kirsner’s inflammatory bowel disease. 6th ed. London: WB Saunders; 2004:340-356.

42. Drossman DA, Talley NJ, Olden KW, et al. Sexual and physical abuse and gastrointestinal illness: Review and recommendations. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:782-94.

43. Drossman DA, Li Z, Leserman J, et al. Health status by gastrointestinal diagnosis and abuse history. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:999-1007.

44. Ringel Y, Drossman DA, Leserman JL, et al. Effect of abuse history on pain reports and brain responses to aversive visceral stimulation: An FMRI study. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:396-404.

45. Drossman DA, Ringel Y, Vogt B, et al. Alterations of brain activity associated with resolution of emotional distress and pain in a case of severe IBS. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:754-61.

46. Alexander F. Psychosomatic medicine: Its principles and applications. New York: WW Norton; 1950.

47. Drossman DA, Chang L. Psychosocial factors in the care of patients with GI disorders. In: Yamada T, editor. Textbook of gastroenterology. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 2003:636-654.

48. Murray CD, Flynn J, Ratcliffe L, et al. Effect of acute physical and psychological stress on gut autonomic innervation in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1695-703.

49. Drossman DA, McKee DC, Sandler RS, et al. Psychosocial factors in the irritable bowel syndrome. A multivariate study of patients and nonpatients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:701-8.

50. Lane RD. Neural substrates of implicit and explicit emotional processes: A unifying framework for psychosomatic medicine. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:214-31.

51. Sifneos PE. The prevalence of “alexyithymic” characteristics in psychsomatic patients. Psychother Psychosom. 1973;22:255-62.

52. Nyklicek I, Vingerhoets AJ. Alexithymia is associated with low tolerance to experimental painful stimulation. Pain. 2000;85:471-5.

53. Portincasa P, Moschetta A, Baldassarre G, et al. Pan-enteric dysmotility, impaired quality of life and alexithymia in a large group of patients meeting ROME II criteria for irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2293-9.

54. Verissimo R, Mota-Cardoso R, Taylor G. Relationships between alexithymia, emotional control, and quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Psychother Psychosom. 1998;67:75-80.

55. Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1984.

56. Bitton A, Dobkin PL, Edwardes MD, et al. Predicting relapse in Crohn’s disease: A biopsychosocial model. Gut. 2008;57:1386-92.

57. Drossman DA, Li Z, Leserman J, et al. Effects of coping on health outcome among female patients with gastrointestinal disorders. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:309-17.

58. Lackner JM, Gurtman MB. Pain catastrophizing and interpersonal problems: A circumplex analysis of the communal coping model. Pain. 2004;110:597-604.

59. Granot M, Ferber SG. The roles of pain catastrophizing and anxiety in the prediction of postoperative pain intensity. Clin J Pain. 2006;21:439-45.

60. Lackner JM, Quigley BM. Pain catastrophizing mediates the relationship between worry and suffering in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:943-57.

61. Berkman LF. The relationship of social networks and social support to morbidity and mortality. In: Cohen S, Syme SL, editors. Social support and health. New York: Academic Press; 1985:241-262.

62. Sewitch MJ, Abrahamowicz M, Bitton A, et al. Psychological distress, social support, and disease activity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1470-9.

63. Moskovitz DN, Maunder RG, Cohen Z, et al. Coping behavior and social support contribute independently to quality of life after surgery for inflammatory bowel disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:517-21.

64. Caso JR, Leza JC, Menchen L. The effects of physical and psychological stress on the gastro-intestinal tract: Lessons from animal models. Curr Mol Med. 2008;8:299-312.

65. Jones MP, Dilley JB, Drossman D, Crowell MD. Brain-gut connections in functional GI disorders: Anatomic and physiologic relationships. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18:91-103.

66. Hinkle LE. The concept of “stress” in the biological and social sciences. In: Lipowski ZJ, Lipsitt DR, Whybrow PC, editors. Psychosomatic medicine. Current trends and clinical applications. New York: Oxford University Press; 1977:27-49.

67. Drossman DA, Sandler RS, McKee DC, Lovitz AJ. Bowel patterns among subjects not seeking health care: Use of a questionnaire to identify a population with bowel dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:529-34.

68. Cannon WB. The movements of the intestine studied by means of roentgen rays. Am J Physiol. 1902;6:251-77.

69. Pavlov I. The work of the digestive glands, 2nd ed. London: C Griffen; 1910.

70. Beaumont W. Nutrition classics. Experiments and observations on the gastric juice and the physiology of digestion. Plattsburgh, NY: FP Allen; 1833.

71. Wolf S, Wolff HG. Human Gastric function: An experimental study of a man and his stomach. London: Oxford University Press; 1943.

72. Engel GL, Reichsman F, Segal HL. A study of an infant with gastric fistula. I. Behavior and the rate of total hydrochloric acid secretion. Psychosom Med. 1956;18:374-98.

73. Young LD, Richter JE, Anderson KO, et al. The effects of psychological and environmental stressors on peristaltic esophageal contractions in healthy volunteers. Psychophysiology. 1987;24:132-41.

74. Holtmann G, Singer MV, Kriebel R, et al. Differential effects of acute mental stress on interdigestive secretion of gastric acid, pancreatic enzymes, and gastroduodenal motility. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:1701-7.

75. Kellow JE, Langeluddecke PM, Eckersley GM, et al. Effects of acute psychologic stress on small-intestinal motility in health and the irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27:53-8.

76. Welgan P, Meshkinpour H, Beeler M. Effect of anger on colon motor and myoelectric activity in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:1150-6.

77. Rao SSC, Hatfield RA, Suls JM, Chamberlain MJ. Psychological and physical stress induce differential effects on human colonic motility. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:985-90.

78. Tache Y, Martinez V, Million M, Rivier J. Corticotropin-releasing factor and the brain-gut motor response to stress. Can J Gastroenterol. 1999;13(Suppl A):18A-25A.

79. Nozu T, Kudaira M. Corticotropin-releasing factor induces rectal hypersensitivity after repetitive painful rectal distention in healthy humans. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:740-4.

80. Wood JD, Grundy D, Al-Chaer ED, et al. Fundamentals of neurogastroenterology: Basic science. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, et al, editors. Rome III: The functional gastrointestinal disorders. 3rd ed. McLean, Va: Degnon Associates; 2006:31-87.

81. Abell TL, Adams KA, Boles RG, et al. Cyclic vomiting syndrome in adults. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:269-84.

82. Rainville P, Duncan GH, Price DD, et al. Pain affect encoded in human anterior cingulate but not somatosensory cortex. Science. 1997;277:968-71.

83. Coderre TJ, Katz J, Vaccarino AL, Melzack R. Contribution of central neuroplasticity to pathological pain: Review of clinical and experimental evidence. Pain. 1993;52:259-85.

84. Ruda MA, Ling QD, Hohmann AG, et al. Altered nociceptive neuronal circuits after neonatal peripheral inflammation. Science. 2000;289:628-30.

85. Al-Chaer ED, Kawasaki M, Pasricha PJ. A new model of chronic visceral hypersensitivity in adult rats induced by colon irritation during postnatal development. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1277-85.

86. Kellow JE, Azpiroz F, Delvaux M, et al. Principles of applied neurogastroenterology: Physiology/motility-sensation. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, et al, editors. Rome III: The functional gastrointestinal disorders. 3rd ed. McLean, Va: Degnon Associates; 2006:89-160.

87. Halvorson HA, Schlett CD, Riddle MS. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome—a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1894-9.

88. Spiller RC. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1662-71.

89. Gwee KA, Leong YL, Graham C, et al. The role of psychological and biological factors in postinfective gut dysfunction. Gut. 1999;44:400-6.

90. Drossman DA. Mind over matter in the postinfective irritable bowel. Gut. 1999;44:306-7.

91. Dunlop SP, Jenkins D, Neal KR, Spiller RC. Relative importance of enterochromaffin cell hyperplasia, anxiety and depression in post-infectious IBS. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1651-9.

92. Barbara G, Wang B, Stanghellini V, et al. Mast cell–dependent excitation of visceral-nociceptive sensory neurons in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:26-37.

93. Vogt BA, Watanabe H, Grootoonk S, Jones AKP. Topography of diprenorphine binding in human cingulate gyrus and adjacent cortex derived from coregistered PET and MR images. Human Brain Mapping. 1995;3:1-12.

94. Vogt BA, Sikes RW. The medial pain system, cingulate cortex, and parallel processing of nociceptive information. In: Mayer EA, Saper CB, editors. The biological basis for mind body interactions. Los Angeles: Elsevier Science; 2000:223-235.

95. Drossman DA. Brain imaging and its implications for studying centrally targeted treatments in IBS: A primer for gastroenterologists. Gut. 2005;54:569-73.

96. Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, et al, editors. Rome III: The functional gastrointestinal disorders. 3rd ed. McLean, Va: Degnon Associates; 2006:487-555.

97. Naliboff BD, Derbyshire SWG, Munakata J, et al. Cerebral activation in irritable bowel syndrome patients and control subjects during rectosigmoid stimulation. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:365-75.

98. Chang L, Berman S, Mayer EA, et al. Brain responses to visceral and somatic stimuli in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with and without fibromyalgia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1354-61.

99. Vogt BA, Hof PR, Vogt LJ. Cingulate gyrus. In: Paxinos G, Mai JK, editors. The human nervous system. 2nd ed. San Diego, Calif, and New York: American Press; 2002:915-946.

100. Mertz H, Morgan V, Tanner G, et al. Regional cerebral activation in irritable bowel syndrome and control subjects with painful and nonpainful rectal distension. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:842-8.

101. Ringel Y, Drossman DA, Turkington TG, et al. Regional brain activation in response to rectal distention in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and the effect of a history of abuse. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1774-81.

102. Silverman DHS, Brody AL, Saxena S, et al. Somatization in clinical depression is associated with abnormal function of a brain region active in visceral pain perception [abstract]. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:A839.

103. Shin LM, McNally RJ, Kosslyn SM, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow during script-driven imagery in childhood sexual abuse-related PTSD: A PET investigation. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:575-84.