CHAPTER 13 Biological treatments

Psychopharmacology

Medications in psychiatry are used not only to reduce symptoms and modify maladaptive behaviour, but also to facilitate psychological therapies of various kinds. Many patients with mental disorders are significantly more vigilant and more anxious about changes in bodily sensations than other people. Thus, ‘side effects’ tend to be more often identified and more often found to be poorly tolerable. However, tolerance usually improves with persistence and patients should be advised of this. It is essential that patients are made aware of common side effects as well as the risk of less common ones (particularly when potentially very serious or life-threatening). The majority of patients find being aware of potential problems and their management reassuring.

Drug interactions

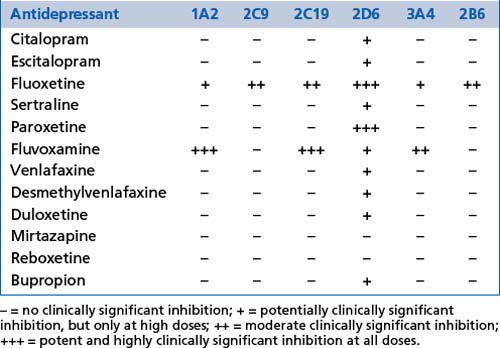

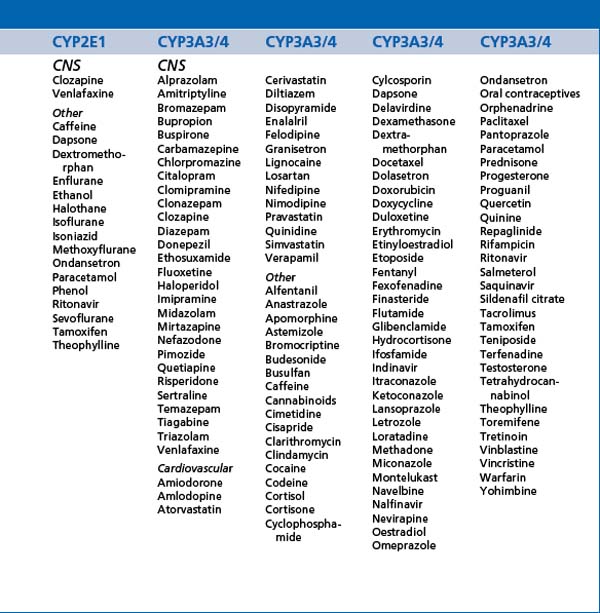

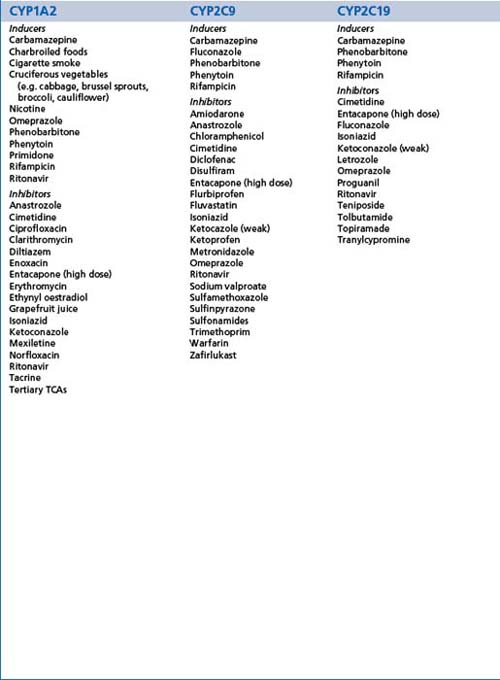

Most medications are metabolised, at least to some extent, in the liver by the cytochrome P450 enzyme group (CYP enzymes) and this includes most psychotropic medications. A number of psychotropic medications inhibit or induce isoenzymes of this enzyme group creating potentially significant changes in the blood levels of other medications. Inhibition will promote increased levels and induction will promote decreased levels. These effects need to be considered in the prescribing of medication combinations and must be considered before prescribing. CYP polymorphisms and levels vary from person to person, and also over different racial groups. Genetic testing is now available to determine the profile of these polymorphisms if there are specific clinical indications (see Tables 13.1, 13.2 and 13.3).

ABC membrane transport proteins (ATP-bound cassette membrane proteins) are heavily involved in the regulation of transport of multiple substances across cell membranes, including the gut, blood-brain barrier, placenta, kidneys and other organs. P-glycoprotein (Pgp) is one such membrane transport protein which has a significant role in the regulation of transport of medications and other substances and therefore pharmacokinetics (including drug interactions). Most psychotropic medications cross the blood-brain barrier by passive diffusion through their lipophilic characteristics, but Pgp can modify transfer against concentration gradients. A number of medications inhibit Pgp and therefore have interactive effects on the action of other medications. Examples of such inhibitors include most selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonergic and noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (with the currently known exception of desmethylvenlafaxine), atypical antipsychotics such as risperidone and olanzapine (less so paliperidone) and a variety of other medications. The tendency of Pgp to have common substrates with the CYP3A group of enzymes can also cause alterations in the bioavailability of several medications. Finally, various neurological diseases alter Pgp activity at the blood-brain barrier.

The combination of antidepressants in the treatment of depressive disorders is an area of some controversy and any combinations should be approached cautiously and with attention to relative effects on CYP enzymes and Pgp. Most medications are carried in the blood bound to proteins. As many share the same carrier proteins, competition alters the level of ‘free’ drug and therefore effect. Alterations in the levels of warfarin, for example, are commonly important (Box 13.1).

Absorption

Medication absorption and therefore bioavailability is affected by:

Hepatic and renal dysfunction

Hepatic and/or renal diseases may interfere with medication metabolism and/or excretion.

Age

The very young and the aged exhibit differences in fat/lean body ratios, medication absorption from the gut, hepatic and renal function, and tolerance of side effects from medications (see Chs 16 and 17).

BOX 13.2 Practical notes

Hypericum perforatum (St John’s Wort) has weak antidepressant properties and contains a group of substances which have antidepressant properties. Combination with serotonergic antidepressants can provoke a serotonin syndrome (Box 13.1). Several medicinal herbs either induce or inhibit CYP enzymes. Combination of these with psychotropic medications requires specific enquiry for each case.

Specific medications

The categories used to classify medications are chosen by the manufacturer when first applying for registration with regulatory authorities. This means that medications may have multiple applications but be ‘known’ by their initial categorisation. Dose ranges given are daily and are suggested for ‘routine’ applications, but exceptions may arise. Side effects listed are those encountered commonly in clinical practice and those which are of particular seriousness. More detailed and comprehensive lists of side effects can be obtained from the ‘References and further reading’ and various printed and electronic prescribing guides.

Most psychotropic medications reduce the seizure threshold, but some have more potent effects than others and will be highlighted in the text.

Anxiolytics

Mode of action

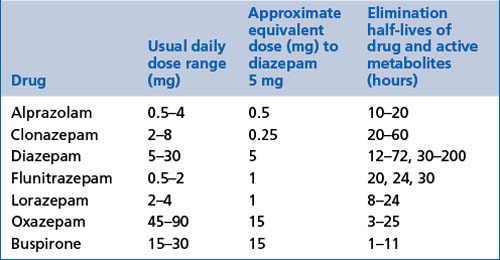

Benzodiazepines act through activation of GABA receptors (the brain’s ‘braking system’), reducing neuronal arousal generally. Buspirone is a serotonin receptor-1A partial agonist, providing optimal serotonergic activity. Clinical notes on anxiolytics are provided in Box 13.3.

Benzodiazepines

These include alprazolam, clonazepam, diazepam, flunitrazepam, lorazepam and oxazepam (see Table 13.4).

General comments

Adverse effects

Benzodiazepines can interfere with cognition, including memory, balance and reaction times, and may be addictive over time.

Benzodiazepines can interfere with cognition, including memory, balance and reaction times, and may be addictive over time. When combined with alcohol or other sedative medications, benzodiazepines amplify sedation and increase the adverse effect upon reaction times, reflexes and cognitive functions generally.

When combined with alcohol or other sedative medications, benzodiazepines amplify sedation and increase the adverse effect upon reaction times, reflexes and cognitive functions generally.Antidepressants

General comments

All antidepressants relieve core symptoms and signs of depressive disorders with biological features (see Ch 6).

All antidepressants relieve core symptoms and signs of depressive disorders with biological features (see Ch 6). They are also very effective in the treatment of all forms of anxiety disorders and particularly useful in treatment-resistant panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

They are also very effective in the treatment of all forms of anxiety disorders and particularly useful in treatment-resistant panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Response in depressive disorders usually takes at least 1 week to be evident and 2 or more weeks to become significant. Optimal response will take several months.

Response in depressive disorders usually takes at least 1 week to be evident and 2 or more weeks to become significant. Optimal response will take several months. Response in anxiety disorders is slower than for depressive disorders (3–4 weeks) and usually requires relatively higher doses. Start with a low dose to minimise aggravation of anxiety early and increase gradually. Concurrent use of a benzodiazepine may be useful early in this treatment.

Response in anxiety disorders is slower than for depressive disorders (3–4 weeks) and usually requires relatively higher doses. Start with a low dose to minimise aggravation of anxiety early and increase gradually. Concurrent use of a benzodiazepine may be useful early in this treatment. Choice of antidepressant is usually initially based upon prominent symptoms (e.g. prominent anxiety might suggest a sedating antidepressant first), response, side effect profile and prescriber preference.

Choice of antidepressant is usually initially based upon prominent symptoms (e.g. prominent anxiety might suggest a sedating antidepressant first), response, side effect profile and prescriber preference. Inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) may occur and result in hyponatraemia (most commonly with SSRIs and SNRIs). Symptoms may include lethargy, muscle weakness, impaired concentration, and potentially hypotension and cardiac arrhythmias. The effect is usually temporary. It is most common in elderly patients. Fluid restriction for a week or more may be required or the medication may need to be changed.

Inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) may occur and result in hyponatraemia (most commonly with SSRIs and SNRIs). Symptoms may include lethargy, muscle weakness, impaired concentration, and potentially hypotension and cardiac arrhythmias. The effect is usually temporary. It is most common in elderly patients. Fluid restriction for a week or more may be required or the medication may need to be changed. The metabolism and therefore pharmacokinetics of most antidepressants are affected by polymorphisms of CYP enzymes (e.g. as found in racial variations). Desmethylvenlafaxine is not.

The metabolism and therefore pharmacokinetics of most antidepressants are affected by polymorphisms of CYP enzymes (e.g. as found in racial variations). Desmethylvenlafaxine is not. Suicide and the use of antidepressant medications has been the subject of intense discussion and research. The current findings of this research are summarised in Box 13.4.

Suicide and the use of antidepressant medications has been the subject of intense discussion and research. The current findings of this research are summarised in Box 13.4.BOX 13.4 Antidepressants and the risk of suicide

BOX 13.5 Clinical notes on antidepressants

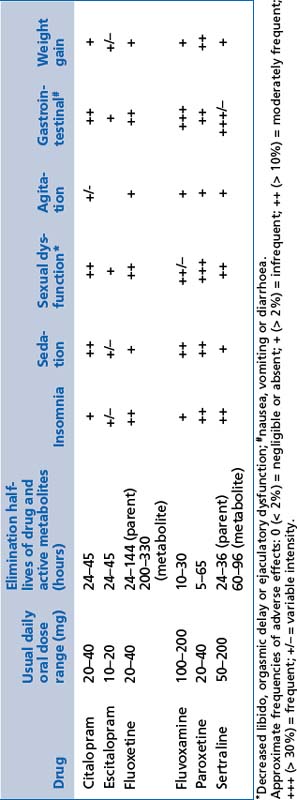

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

These include citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine and sertraline (see Table 13.5).

General comments

Adverse effects

There may be disturbed sleep with initial and/or middle insomnia (unpleasant wakefulness after a period of sleep, followed by further sleep).

There may be disturbed sleep with initial and/or middle insomnia (unpleasant wakefulness after a period of sleep, followed by further sleep). There may be sexual dysfunction, including orgasmic delay and suppression of libido; it improves with time and sexual activity; it is particularly significant for females.

There may be sexual dysfunction, including orgasmic delay and suppression of libido; it improves with time and sexual activity; it is particularly significant for females. Movement disorders such as restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movement disorder and bruxism may be aggravated.

Movement disorders such as restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movement disorder and bruxism may be aggravated. Platelet adhesion and function is mildly impaired and may result in bruising, an increase in bleeding time and increased risk of gastric bleeding (clotting factors are not affected).

Platelet adhesion and function is mildly impaired and may result in bruising, an increase in bleeding time and increased risk of gastric bleeding (clotting factors are not affected).Serotonergic and noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

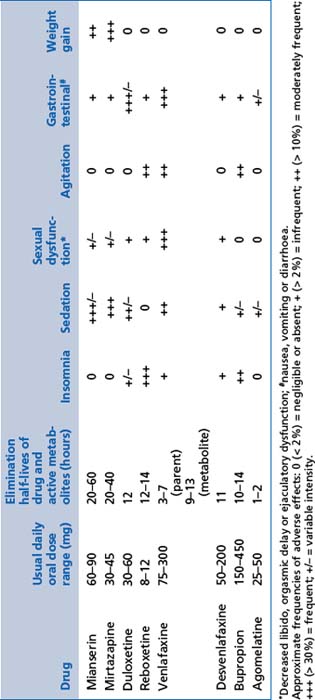

These include desvenlafaxine, duloxetine and venlafaxine. Details of dose range, half-lives and adverse effects can be found in Table 13.6.

Adverse effects

There may be similar unwanted effects to SSRIs; side effects with venlafaxine appear clinically more severe than duloxetine and desvenlafaxine.

There may be similar unwanted effects to SSRIs; side effects with venlafaxine appear clinically more severe than duloxetine and desvenlafaxine. Withdrawal should be very gradual, as discontinuation can be very uncomfortable (dizziness, light-headedness, insomnia, agitation and irritability); it appears to be most severe for venlafaxine and less severe for duloxetine and desvenlafaxine.

Withdrawal should be very gradual, as discontinuation can be very uncomfortable (dizziness, light-headedness, insomnia, agitation and irritability); it appears to be most severe for venlafaxine and less severe for duloxetine and desvenlafaxine.Selective noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors (NRIs)

These include reboxetine (see Table 13.6).

Indications

Noradrenaline and specific serotonergic agents (NASAs)

These include mianserin and mirtazapine (see Table 13.6).

Mode of action

Adverse effects

NASAs are very sedating and weight gain can be a significant problem; the effect decreases with increasing dose (reverse of that usually expected).

NASAs are very sedating and weight gain can be a significant problem; the effect decreases with increasing dose (reverse of that usually expected).Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs)

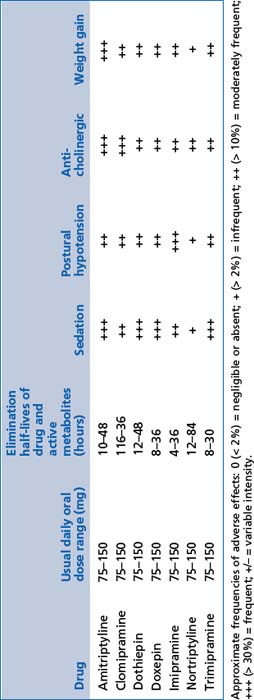

These include amitriptyline, nortriptyline, dothiepin, doxepin, imipramine, clomipramine and trimipramine (see Table 13.7).

General comments

Mode of action

By reducing the reuptake of serotonin and noradrenaline after release from pre-synaptic terminals, and by enhancing noradrenaline and dopamine release through inhibition of serotonin 2a receptors, these medications improve the capacity of the brain to recover optimal function during depressive disorders or severe anxiety. Neurotrophic factor release is significantly enhanced, but the mechanism remains uncertain.

By reducing the reuptake of serotonin and noradrenaline after release from pre-synaptic terminals, and by enhancing noradrenaline and dopamine release through inhibition of serotonin 2a receptors, these medications improve the capacity of the brain to recover optimal function during depressive disorders or severe anxiety. Neurotrophic factor release is significantly enhanced, but the mechanism remains uncertain.Noradrenaline and dopamine reuptake inhibitors

These include bupropion (see Table 13.6).

Indications

Noradrenaline and dopamine reuptake inhibitors are indicated in depressive disorders and smoking cessation.

Noradrenaline and dopamine reuptake inhibitors are indicated in depressive disorders and smoking cessation.Serotonin receptor antagonists/melatonin receptor agonists

These include agomelatine (see Table 13.6).

Indications

Serotonin receptor antagonists/melatonin receptor agonists are indicated in depressive and anxiety disorders with significant somatic/melancholic symptoms.

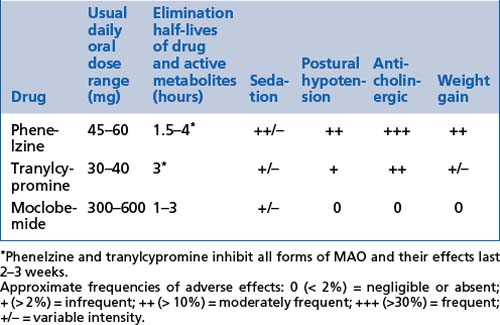

Serotonin receptor antagonists/melatonin receptor agonists are indicated in depressive and anxiety disorders with significant somatic/melancholic symptoms.Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)

These include moclobemide, phenelzine and tranylcypromine (see Tables 13.8, 13.9 and 13.10).

Indications

Adverse effects

Reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase type A (RIMAs) are very well tolerated but are often not effective. Their relatively select inhibition of the A type of monoamine oxidase (MAO) is advantageous, as this is found mostly in the brain and much less often in the gut. Consequently, the risk of excessive tyramine absorption from certain foods is very much lower (not absent) and use of the medications much safer and easier.

Reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase type A (RIMAs) are very well tolerated but are often not effective. Their relatively select inhibition of the A type of monoamine oxidase (MAO) is advantageous, as this is found mostly in the brain and much less often in the gut. Consequently, the risk of excessive tyramine absorption from certain foods is very much lower (not absent) and use of the medications much safer and easier. MAOIs carry dietary restrictions because of increased tyramine absorption from foods (by reducing destruction by MAO in the bowel).

MAOIs carry dietary restrictions because of increased tyramine absorption from foods (by reducing destruction by MAO in the bowel). Introduction of tyramine in foods or in combination with serotonergic substances can result in rapid and severe hypertension, which can result in a cerebrovascular accident and even death (see Table 13.9).

Introduction of tyramine in foods or in combination with serotonergic substances can result in rapid and severe hypertension, which can result in a cerebrovascular accident and even death (see Table 13.9). Treatment can include sedation (e.g. with benzodiazepines), analgesia and vasodilating medications (e.g. phentolamine/diazoxide/nifedipine). General medical intervention with admission to hospital must be obtained urgently if any such symptoms or a rise in blood pressure occurs.

Treatment can include sedation (e.g. with benzodiazepines), analgesia and vasodilating medications (e.g. phentolamine/diazoxide/nifedipine). General medical intervention with admission to hospital must be obtained urgently if any such symptoms or a rise in blood pressure occurs.| High tyramine content: not permitted | Moderate tyramine content: limited amounts are safe | Low tyramine content: permissible and safe |

|---|---|---|

TABLE 13.10 MAOI dangerous combinations

| Amphetamines |

| Pethidine |

| Opioids |

| Lithium |

| Serotonergic antidepressants |

| Hypericum perforatum |

| Tryptophan |

Antipsychotics

Indications

Antipsychotic medications all relieve psychotic symptoms of any cause to some degree. They reduce the intensity of sensory information drawn from the environment, improve the efficiency of reformulation of environmental stimuli and facilitate processing of information and perceptions. They can then gradually improve reality processing and facilitate more appropriate responses to their internal and external environment.

Antipsychotic medications all relieve psychotic symptoms of any cause to some degree. They reduce the intensity of sensory information drawn from the environment, improve the efficiency of reformulation of environmental stimuli and facilitate processing of information and perceptions. They can then gradually improve reality processing and facilitate more appropriate responses to their internal and external environment. The efficacy is high in schizophrenia, mania and psychotic depression, but variable (sometimes ineffective) in psychosis secondary to general medical disorders or substance use (including prescribed medications), and in delusional disorders.

The efficacy is high in schizophrenia, mania and psychotic depression, but variable (sometimes ineffective) in psychosis secondary to general medical disorders or substance use (including prescribed medications), and in delusional disorders.Clinical notes on the use of antipsychotics are summarised in Box 13.9 on page 177.

Mode of action

All antipsychotics increase production of nerve growth factors in the brain (of considerable importance in schizophrenia particularly) and may have other useful effects upon neuronal and glial function.

All antipsychotics increase production of nerve growth factors in the brain (of considerable importance in schizophrenia particularly) and may have other useful effects upon neuronal and glial function. All of the current antipsychotics have modulating effects upon dopamine activity in the brain and this is directly related to their beneficial effects upon positive features of psychosis (see Ch 5).

All of the current antipsychotics have modulating effects upon dopamine activity in the brain and this is directly related to their beneficial effects upon positive features of psychosis (see Ch 5).Adverse effects

The first generation antipsychotics do not appear to have significant benefit upon negative and cognitive features of psychosis (particularly schizophrenia), and can easily provoke a variety of extrapyramidal side effects (Box 13.6).

The first generation antipsychotics do not appear to have significant benefit upon negative and cognitive features of psychosis (particularly schizophrenia), and can easily provoke a variety of extrapyramidal side effects (Box 13.6). Second generation antipsychotics, called ‘atypical antipsychotics’, are much less likely to produce these side effects (although they can occur).

Second generation antipsychotics, called ‘atypical antipsychotics’, are much less likely to produce these side effects (although they can occur). The second generation antipsychotics have beneficial effects upon negative features of psychosis and cognitive deficits.

The second generation antipsychotics have beneficial effects upon negative features of psychosis and cognitive deficits.BOX 13.6 Extrapyramidal side effects (EPS)

General comments

Acute forms of EPS

Management of acute EPS

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS)

Tardive forms (delayed onset; sometimes many years)

Management of tardive EPS

Metabolic side effects

metabolic syndrome, which may be a combination of weight gain, diabetes mellitus (type 2), hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia (metabolic complications are spontaneously more common in schizophrenia than with other disorders).

metabolic syndrome, which may be a combination of weight gain, diabetes mellitus (type 2), hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia (metabolic complications are spontaneously more common in schizophrenia than with other disorders).Side effects are most prominent with atypical antipsychotics.

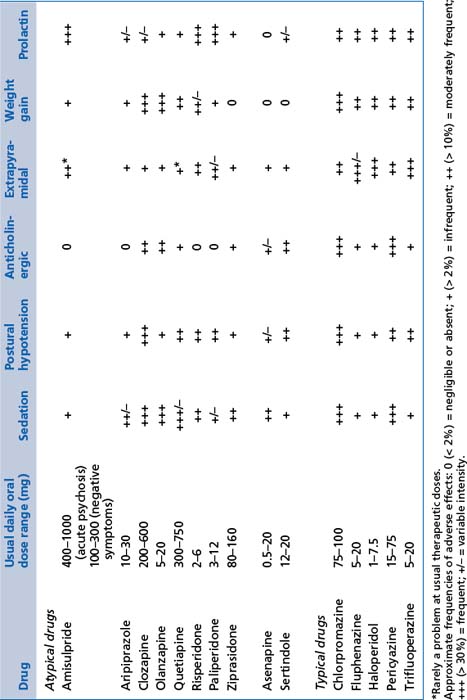

First generation antipsychotics (neuroleptics)

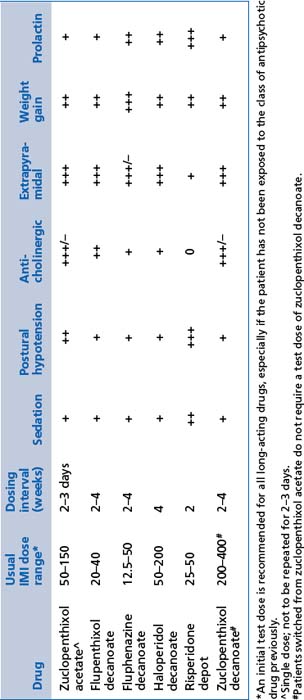

These include chlorpromazine, fluphenazine, flupenthixol, haloperidol, pericyazine, trifluoperazine and zuclopenthixol (see Tables 13.11 and 13.12). Practical notes regarding the use of first generation antipsychotics are summarised in Box 13.7.

TABLE 13.11 Relative frequency of common adverse effects of antipsychotics at usual therapeutic doses

TABLE 13.12 Relative frequency of common adverse effects of depot antipsychotics at usual therapeutic doses (frequency of occurrence of adverse effects, not the intensity with which they occur)

BOX 13.7 Practical notes regarding first generation antipsychotics

BOX 13.8 Clozapine

Second generation antipsychotics (atypicals)

These include amisulpride, aripiprazole, asenapine, clozapine (Box 13.8), olanzapine, paliperidone, risperidone, quetiapine, sertindole and ziprasidone (see Tables 13.11 and 13.12). Note that:

Rapidly disintegrating oral preparations of olanzapine (wafer) and risperidone (tablet) are available.

Rapidly disintegrating oral preparations of olanzapine (wafer) and risperidone (tablet) are available.Mood stabilisers

General comments

Lithium is the most effective mood stabiliser for bipolar affective disorder and neuroprotective in chronic mood disorder.

Lithium is the most effective mood stabiliser for bipolar affective disorder and neuroprotective in chronic mood disorder. Sampling of blood level should occur 10–12 hours after the last dose so that it is at the start of the excretion phase.

Sampling of blood level should occur 10–12 hours after the last dose so that it is at the start of the excretion phase. The therapeutic index is low; aim for blood level between 0.5 and 1.2 millimoles/L; adjust for patient tolerance and efficacy.

The therapeutic index is low; aim for blood level between 0.5 and 1.2 millimoles/L; adjust for patient tolerance and efficacy.Indications

Adverse effects

Lithium may damage the thyroid gland, impeding production and release of thyroid hormones. It is reversible early in the treatment, but may become permanent and require oral thyroid hormone supplements.

Lithium may damage the thyroid gland, impeding production and release of thyroid hormones. It is reversible early in the treatment, but may become permanent and require oral thyroid hormone supplements. It may cause increased urine production (‘nephrogenic diabetes insipidus’). Renal cortical damage can occur and, rarely, renal failure can follow.

It may cause increased urine production (‘nephrogenic diabetes insipidus’). Renal cortical damage can occur and, rarely, renal failure can follow. Toxicity can arise easily if poorly monitored. This is characterised by coarse tremor, dysarthria and ataxia; it is promoted by dehydration.

Toxicity can arise easily if poorly monitored. This is characterised by coarse tremor, dysarthria and ataxia; it is promoted by dehydration.Clinical notes on the use of lithium are summarised in Box 13.10.

Anticonvulsants

These include sodium valproate, carbamazepine and lamotrigine.

Indications

Anticonvulsants are indicated in the management of bipolar mood disorders, both in acute management and in prophylaxis.

Anticonvulsants are indicated in the management of bipolar mood disorders, both in acute management and in prophylaxis.Clinical notes on the use of anticonvulsants are summarised in Box 13.11.

Adverse effects

Adverse effects for sodium valproate, carbamazepine and lamotrigine are:

sodium valproate (dose 500–1000 mg): tremor, weight gain, alopecia (partial), blurred vision, thrombocytopaenia and hepatotoxicity

sodium valproate (dose 500–1000 mg): tremor, weight gain, alopecia (partial), blurred vision, thrombocytopaenia and hepatotoxicity carbamazepine (dose 100–800 mg): skin rash, dizziness, sedation, ataxia, dysarthria, thrombocytopaenia and agranulocytosis, and

carbamazepine (dose 100–800 mg): skin rash, dizziness, sedation, ataxia, dysarthria, thrombocytopaenia and agranulocytosis, andHypnotics

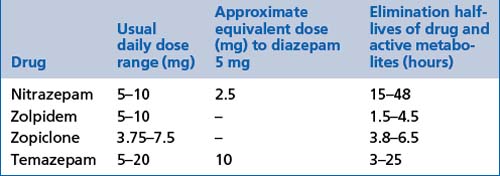

These include benzodiazepines: flunitrazepam, nitrazepam and temazepam (see Tables 13.13 and 13.4).

Imidazopyridines

These include zolpidem (see Table 13.13).

General comments

Other psychotropic medications

Oestrogen supplements

Oestrogen deficiency in females is associated with an increased risk of depressive disorders; it is commonly observed in the perimenopause.

Oestrogen deficiency in females is associated with an increased risk of depressive disorders; it is commonly observed in the perimenopause. Oestrogen supplements facilitate the management of depressive disorders at times of relative deficiency.

Oestrogen supplements facilitate the management of depressive disorders at times of relative deficiency. Oestradiol is the only oestrogen which crosses the blood-brain barrier and is therefore effective in the management of disorders involving brain dysfunction.

Oestradiol is the only oestrogen which crosses the blood-brain barrier and is therefore effective in the management of disorders involving brain dysfunction. Management of schizophrenia in women is also augmented by supplementary oestradiol in doses of 50–100 mg transdermally twice weekly.

Management of schizophrenia in women is also augmented by supplementary oestradiol in doses of 50–100 mg transdermally twice weekly. The mechanism of action appears to include modulation of serotonin, dopamine and neurotrophic factor activity in the brain.

The mechanism of action appears to include modulation of serotonin, dopamine and neurotrophic factor activity in the brain.Medications for attention deficit disorders (ADD)

dexamphetamine (dose 5–30 mg): improves attention and concentration in ADD; insomnia and reduced appetite are common unwanted effects; it is addictive, but is not usually a problem in ADD (correctly diagnosed); a slow release mix of amphetamine salts is available in other countries

dexamphetamine (dose 5–30 mg): improves attention and concentration in ADD; insomnia and reduced appetite are common unwanted effects; it is addictive, but is not usually a problem in ADD (correctly diagnosed); a slow release mix of amphetamine salts is available in other countries methylphenidate (dose 10–30 mg): similar to dexamphetamine and is available in sustained-release preparation, and

methylphenidate (dose 10–30 mg): similar to dexamphetamine and is available in sustained-release preparation, and atomoxetine (dose 10–120 mg): not addictive, but more limited in efficiency and efficacy than the stimulants.

atomoxetine (dose 10–120 mg): not addictive, but more limited in efficiency and efficacy than the stimulants.Clinical notes on the use of medications for ADD are summarised in Box 13.12.

Other stimulants

Modafanil (dose 100–400 mg) may have value in some patients with severe lethargy, apathy or abulia; it is non-addictive, expensive but well tolerated.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

General comments

Always seek specialist advice before prescribing a psychotropic medication to a pregnant or breastfeeding woman.

Always seek specialist advice before prescribing a psychotropic medication to a pregnant or breastfeeding woman. Between 2% and 4% of all live births have some form of congenital deformity, across populations and cultures.

Between 2% and 4% of all live births have some form of congenital deformity, across populations and cultures. No psychotropic medication can be guaranteed safe in pregnancy or during lactation, but relative risks can be defined to some degree (Box 13.13). The fundamental principle is to carefully balance the risks of the patient’s illness against the known risks of the treatment. However, excessive concern over adverse effects upon the fetus can sometimes leave mother and baby at significant risk and the decision about medication should be made carefully. Specialist assistance may be particularly useful.

No psychotropic medication can be guaranteed safe in pregnancy or during lactation, but relative risks can be defined to some degree (Box 13.13). The fundamental principle is to carefully balance the risks of the patient’s illness against the known risks of the treatment. However, excessive concern over adverse effects upon the fetus can sometimes leave mother and baby at significant risk and the decision about medication should be made carefully. Specialist assistance may be particularly useful. All psychotropic medications cross into breast milk, but the concentrations are less than 10% of those in the maternal blood. This means that the risks to the infant are very small. Lithium carries a greater risk because of the possibilities of lithium toxicity and damage to the infant’s thyroid gland, but this risk is also very small.

All psychotropic medications cross into breast milk, but the concentrations are less than 10% of those in the maternal blood. This means that the risks to the infant are very small. Lithium carries a greater risk because of the possibilities of lithium toxicity and damage to the infant’s thyroid gland, but this risk is also very small. Sometimes, mixed formula and breastfeeding or expression of breast milk during ‘troughs’ in medication levels for use later can be helpful, particularly in premature infants.

Sometimes, mixed formula and breastfeeding or expression of breast milk during ‘troughs’ in medication levels for use later can be helpful, particularly in premature infants.Antidepressants during pregnancy and lactation

The length of exposure to pregnant women without evidence of adverse effects suggests that tricyclic antidepressants are relatively safe in pregnancy.

The length of exposure to pregnant women without evidence of adverse effects suggests that tricyclic antidepressants are relatively safe in pregnancy. Sertraline, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine and citalopram/escitalopram appear to be largely safe in pregnancy, but neonatal hypoglycaemia may occur.

Sertraline, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine and citalopram/escitalopram appear to be largely safe in pregnancy, but neonatal hypoglycaemia may occur. SSRIs and particularly venlafaxine/desmethylvenlafaxine can be associated with pulmonary hypertension and discontinuation symptoms after birth. The dose should be progressively reduced before labour begins and can be increased again after delivery.

SSRIs and particularly venlafaxine/desmethylvenlafaxine can be associated with pulmonary hypertension and discontinuation symptoms after birth. The dose should be progressively reduced before labour begins and can be increased again after delivery. Little is known about the safety of duloxetine in pregnancy, but there are no adverse reports at this time.

Little is known about the safety of duloxetine in pregnancy, but there are no adverse reports at this time.Antipsychotics during pregnancy and lactation

Quetiapine has the advantage of significantly lower transmission across the placenta (greater binding to Pgp than other antipsychotics); risperidone and paliperidone appear next most advantageous, and olanzapine next.

Quetiapine has the advantage of significantly lower transmission across the placenta (greater binding to Pgp than other antipsychotics); risperidone and paliperidone appear next most advantageous, and olanzapine next.Mood stabilisers during pregnancy and lactation

Lithium can uncommonly be associated with major deformities of the heart and great vessels, and can also provoke hypotonia (‘floppy-baby’) soon after delivery from lithium toxicity in the infant. Damage to the thyroid gland of the fetus may occur but is rare.

Lithium can uncommonly be associated with major deformities of the heart and great vessels, and can also provoke hypotonia (‘floppy-baby’) soon after delivery from lithium toxicity in the infant. Damage to the thyroid gland of the fetus may occur but is rare. Carbamazepine and valproate are both associated with serious neural tube defects, as well as other deformities in facial bone development. They should be avoided in pregnancy if at all possible. Folic acid supplements (5 mg daily) during pregnancy help to reduce these risks, but are not fully effective.

Carbamazepine and valproate are both associated with serious neural tube defects, as well as other deformities in facial bone development. They should be avoided in pregnancy if at all possible. Folic acid supplements (5 mg daily) during pregnancy help to reduce these risks, but are not fully effective.Adjunctive medications and exercise

Omega-3 fatty acids: there is increasing evidence that supplements containing these fatty acids (e.g. fish oil capsules) may be beneficial in major mood disorders. At least 3000 mg daily is required.

Omega-3 fatty acids: there is increasing evidence that supplements containing these fatty acids (e.g. fish oil capsules) may be beneficial in major mood disorders. At least 3000 mg daily is required. Supplements of 5000 international units per day of vitamin D may be helpful in patients with vitamin D deficiency, which appears common in major mood disorders.

Supplements of 5000 international units per day of vitamin D may be helpful in patients with vitamin D deficiency, which appears common in major mood disorders. N-acetyl cysteine, an amino acid, is converted to glutathione, which is an important antioxidant in the brain. It may enhance the long-term mental state of patients with bipolar disorders and schizophrenia. The recommended dose is 1000 mg twice daily.

N-acetyl cysteine, an amino acid, is converted to glutathione, which is an important antioxidant in the brain. It may enhance the long-term mental state of patients with bipolar disorders and schizophrenia. The recommended dose is 1000 mg twice daily. Regular cardiopulmonary and strength exercises are highly advantageous to patients with psychological disorders of all kinds and are particularly valuable in depressive, bipolar and anxiety disorders.

Regular cardiopulmonary and strength exercises are highly advantageous to patients with psychological disorders of all kinds and are particularly valuable in depressive, bipolar and anxiety disorders.Other biological treatments

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

The nature of ECT

Inducing a generalised seizure has a powerful therapeutic effect upon severe depressive disorders, but not all such seizures are therapeutic.

Inducing a generalised seizure has a powerful therapeutic effect upon severe depressive disorders, but not all such seizures are therapeutic. A seizure is induced by passing an electric current through the frontal lobes, using a pulsed square-wave form.

A seizure is induced by passing an electric current through the frontal lobes, using a pulsed square-wave form. A seizure is necessary but not sufficient to have a therapeutic effect. The extent to which the electrical charge exceeds the threshold for inducing a seizure, specific electrical features of seizure and to some extent transient post-ictal blood pressure and heart rate increases (reflecting increased sympathetic activity) are useful guides to the likely efficacy of treatment.

A seizure is necessary but not sufficient to have a therapeutic effect. The extent to which the electrical charge exceeds the threshold for inducing a seizure, specific electrical features of seizure and to some extent transient post-ictal blood pressure and heart rate increases (reflecting increased sympathetic activity) are useful guides to the likely efficacy of treatment. The treatment is given under a general anaesthetic to allow muscle relaxation and therefore reduced risk of musculoskeletal injury.

The treatment is given under a general anaesthetic to allow muscle relaxation and therefore reduced risk of musculoskeletal injury.Indications for use of ECT

severe melancholic depressive disorder, particularly with psychosis and/or catatonia; improvement is almost always very impressive, particularly with catatonia

severe melancholic depressive disorder, particularly with psychosis and/or catatonia; improvement is almost always very impressive, particularly with catatonia severe depression during pregnancy (relatively safer than medications) and puerperium (where a high risk of injury to mother and infant is present)

severe depression during pregnancy (relatively safer than medications) and puerperium (where a high risk of injury to mother and infant is present)ECT remains the most potent and reliable treatment for severe melancholia and psychotic depression.

Adverse effects

Adverse effects of ECT include:

cognitive impairment, notably memory dysfunction; mostly reversible except for events within days of the treatment

cognitive impairment, notably memory dysfunction; mostly reversible except for events within days of the treatment persistent cognitive impairment has been reported as a rare phenomenon and appears related to multiple factors

persistent cognitive impairment has been reported as a rare phenomenon and appears related to multiple factors transient cardiac dysrhythmias (mostly harmless unless accompanied by preexisting cardiac pathology)

transient cardiac dysrhythmias (mostly harmless unless accompanied by preexisting cardiac pathology)Structural brain injury does not occur, despite many claims to the contrary.

References and further reading

Aszalos A. Drug–drug interactions affected by the transporter protein, P-glycoprotein (ABCB1, MDR1) II. Clinical Aspects Drug Discovery Today. 2007:838-843. 12(19/20)

Castle D., Copolov D., Wykes T., Mueser K. Pharmacological and psychosocial treatments in schizophrenia. London: Informa UK; 2008.

Dowden J., Allardice J., Ames D., et al. Therapeutic guidelines: psychotropic version. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines; 2008.

Janicak P., Davis J., Preskorn S., et al. Principles and practice of psychopharmacotherapy. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2006.

Menon S. Psychotropic medication during pregnancy and lactation. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2008;277(1):1-13.

Rosenbaum J., Arana G., Hyman S., et al. Handbook of psychiatric drug therapy. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005.

Schatzberg A., Nemeroff C. Essentials of clinical psychopharmacology. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2006.

Stahl S. Essential psychopharmacology. The prescriber’s guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

Tiller J., Lyndon R., editors. Electroconvulsive therapy. An Australasian guide. Melbourne: Australian Postgraduate Medicine, 2003.

Weiner R., Fink M., Hammersley D., et al. The practice of electroconvulsive therapy: recommendations for treatment, training and privileging. In Task Force Report of the American Psychiatric Association. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1990.

Wiznen P., Op Den Buijsch R., Drent M., et al. the prevalence and clinical relevance of cytochrome P450 polymorphisms. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2007;26(Suppl 2):211-219. Review article