CHAPTER 25 Biologic Augmentation Devices

Augmentation for rotator cuff surgery has been at the forefront of research and development in recent years, yielding several products, most of which have not acquired widespread popularity. Xenograft materials are available, including porcine small intestine submucosa (SIS) (Restore Orthobiologic Soft Tissue Implant, DePuy Orthopaedics, Warsaw, Ind), fetal bovine dermis (TissueMend Soft Tissue Repair Matrix, Stryker Orthopaedics, Mahwah, NJ), porcine dermal collagen—Zimmer Collagen Repair Patch (Zimmer, Warsaw, Ind) and Permacol (Tissue Science Laboratories, Aldershot, UK), equine pericardium (OrthADAPT Bioimplant, Pegasus Biologics, Irvine, Calif). Some reported problems with these grafts include foreign body reactions mimicking infection, suture pull-out, loss of range of motion, and clinical failure.1–8 Synthetic materials are also available for augmentation, including polyurethane urea bands (Artelon, Artimplant, Lansdale, Pa), knitted polyester, polyethylene terephthalate, fiber mesh (Mersilene mesh, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) and the expanded polytetrafluoroethylene patch (Gore-Tex Expanded PTFE Patch, W.L. Gore & Associates, Flagstaff, Ariz). There are limited reports with these synthetic materials in rotator cuff surgery and the failures have stemmed from foreign body reaction, bone resorption, and retears at the graft tendon junction.9–13

As early as 1978, human allograft tissue was used for augmentation of rotator cuff defects. These initial attempts with freeze-dried allograft tissue had mixed results. Acute rejection, infection, and clinical failure have limited its use.14,15 Presently, the allograft of choice is acellular human dermal matrix, GJA (GRAFTJACKET Matrix, Wright Medical Technology, Arlington, Tenn). This material is an aseptically handled, acellular human dermal tissue that is processed to maintain an intact collagen structure while avoiding cross linking. The GRAFTJACKET has proven to be a good matrix for in situ tissue engineering in tenocyte models and has demonstrated superior biomechanical properties in cadaveric studies.16,17 Histiologic and biomechanical data have been very promising in rat, canine and, most recently, primate models.18–20 Postoperative biopsy at 3 months of one patient demonstrated cellular and blood vessel infiltration, lack of inflammatory response, and neotendon formation.21 This material has demonstrated promising initial clinical results at several centers and is our preferred augmentation device.22–26

ANATOMY AND PATHOANATOMY

Basic rotator cuff anatomy is covered elsewhere in this text. Here we will focus on the anatomic changes relevant to large tears. Massive retracted tears pose unique anatomic constraints. They are associated with muscle atrophy and eventually fatty infiltration, which progresses with increasing size and duration of the tear. Even with successful repairs, only a portion of the atrophy is reversed and fatty infiltration remains constant. The tendons themselves can become degenerative and fibrotic. Superior migration of the humeral head can occur, making a primary repair even more difficult. Many massive rotator cuff tears can be repaired primarily using interval scar releases and margin convergence. In some cases, the final construct may have significant tension, with poor-quality tissue and even a residual defect. In these cases, it might be beneficial to add a patch augmentation to supplement the repair because the risk for retear is high. When primary repair is impossible, it is important to have the ability to bridge the gap with a biologic augmentation device. Currently, there are no tissue replacement devices approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for bridging gaps larger than 1 cm.

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

Four standard views of the shoulder are obtained in all patients with rotator cuff problems:

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

The indications and contraindications for bridging and augmentation of rotator cuff defects are still being defined. For bridging, the best demographic factor is motivated patients younger than 60 years with massive irreparable tears who have severe disabling pain and well-maintained active motion. An intact biceps tendon is helpful because it facilitates sewing the graft in anteriorly. Fatty infiltration of the rotator cuff musculature and superior migration of the humeral head are acceptable variables. Augmentation is typically used for tears that are at risk for failure with primary repair. These include rotator cuffs with repairs under tension, chronic large tears, fatty degeneration, poor tendon quality, or a small residual defect following a large repair. Age is a confounding variable because older patients are more at risk for retear but are also less likely to incorporate the graft successfully, likely because of the senescence of mesenchymal stem cells.26

Relative contraindications for both procedures include moderate glenohumeral osteoarthritis or rotator cuff arthropathy, immunocompromised state, and heavy smoking. Patients older than 60 years are potential candidates but outcomes may not be equivalent to those in the younger age group.26 Older patients with cuff tears, osteoarthritis, restricted motion, and little pain are not candidates for this procedure. These patients are best served with a reverse total shoulder arthroplasty.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Treatment options for massive rotator cuff tears are limited in the very young population. Primary repair, either arthroscopically or with a miniopen repair, is possible. Repairing massive tears with compromised tissues dramatically increases the risk of failure with either technique. In this situation, it is best to augment with a biologic scaffold to reinforce the tenuous repair. In our opinion, alternatives to repair, such as reverse total shoulder arthroplasty, latissimus dorsi transfer, glenohumeral joint fusion, and arthroscopic débridement with partial repair, are second attempts, or salvage may be considered if the allograft fails. In addition to other shortcomings, these are all nonanatomic solutions. Latissimus dorsi transfers have demonstrated good results in certain patient populations but the postoperative immobilization is likely tolerated only by the most compliant of patients.27,28 Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty appears to be a good option for patients older than 70 years with limited function.29 In the younger population, arthroplasty plays a small role because of the possibility of multiple revision surgeries over the long term. Glenohumeral joint arthrodesis sometimes offers excellent pain relief but function is limited when compared with other techniques that preserve the glenohumeral joint.30 For the very young patient, the best option is probably patch augmentation with acellular human dermal matrix (GJA; Wright Medical Technology). There is a burgeoning interest in nonstructural biologic options, including bone morphogenic proteins and growth factors. In the future, these could be added to primary repairs or grafts to improve rotator cuff healing rates.31

Arthroscopic Techniques

Patch Augmentation of Rotator Cuff Tears

The technique described here is for augmentation of primarily repaired rotator cuff tears that appear to be at risk for failure. At-risk repairs include those with residual defects, poor-quality tissue, size larger than 3 cm, and previous failed repair attempts. The technique for biologic rotator cuff replacement has been described.23

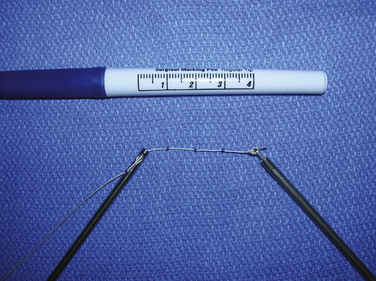

Graft Measurement.

Accurate measurements of the tear are needed to appropriately size the graft. The knotted suture device allows simple and precise measurement of the dimensions of the tear (Fig. 25-1). It is an arthroscopic measurement tool made of braided suture with knots placed 1 cm apart that can be pulled through a knot pusher. The length is measured between the tip of the knot pusher on one of the knots and a grasper that holds the free end of the device (Fig. 25-2). In the medial to lateral dimension, 1 cm of graft will overlap the tuberosity and an additional 1 cm will overlap the repaired cuff; 6 mm should be added to the mediolateral and anteroposterior dimensions to allow for suture placement 3 mm from each edge.

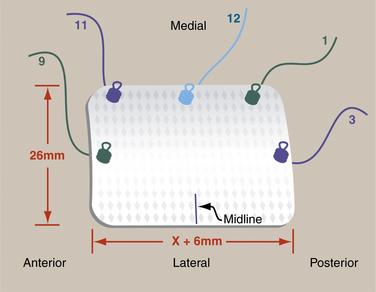

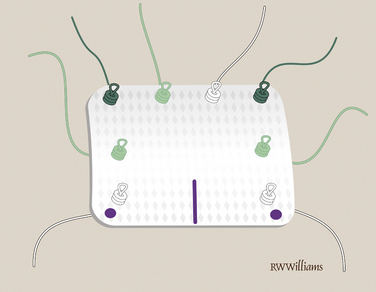

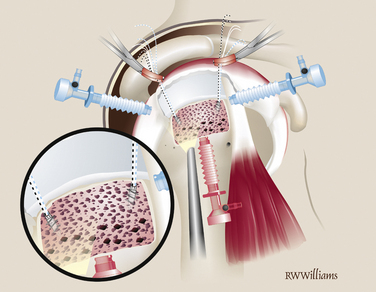

Graft Preparation.

The graft is cut on the back table and the midline of the lateral aspect of the graft is marked with a sterile marking pen. Five short-tail interference knotted (STIK) sutures are then passed with a Keith needle from top to bottom through the anterior, medial, and posterior portions of the graft, 3 mm from the edge. The sutures are passed at the 9, 11, 12, 1, and 3 o’clock positions on the graft (Fig. 25-3). A STIK suture is a permanent braided no. 2 suture with a mulberry interference knot tied at one end, allowing for control of the graft using a single pass of the suture.

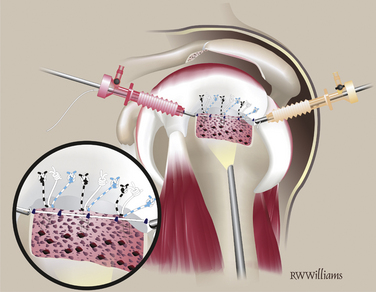

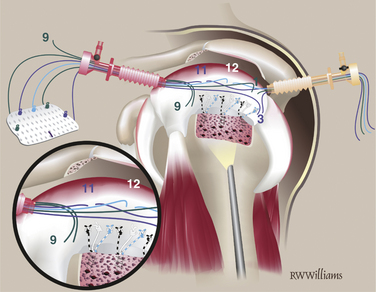

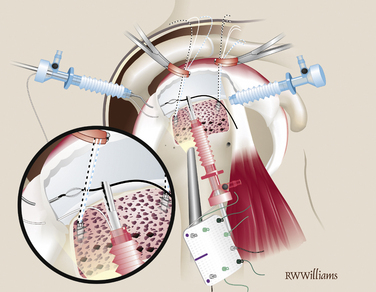

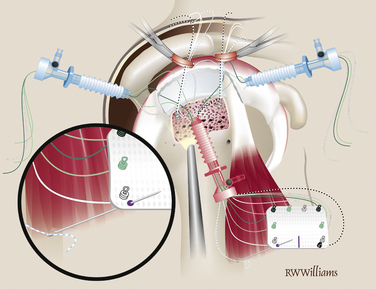

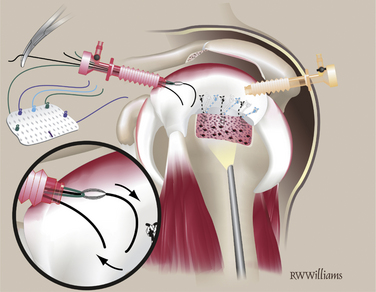

Suture Passing.

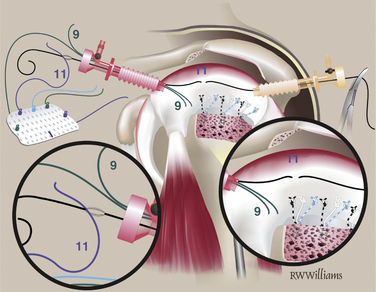

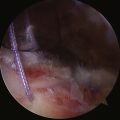

The STIK sutures are passed in order, starting with the anterior suture (9 o’clock) and progressing toward the posterior stitch. All sutures are shuttled with a 45- or 60-degree suture hook to pass Suture Shuttles (Conmed Linvatec, Largo, Fla). The position of the first STIK and each subsequent STIK suture can be estimated using a knotted suture measuring device. All sutures are passed while viewing from the lateral portal and working from the posterior portal. The anterior-most stitch is the exception; it is not easily approached from the posterior portal. Instead, the suture hook is introduced through the anterior portal and passed through the anterior cuff, just anterior to the primary rotator cuff repair. Several inches of suture shuttle are fed into the joint; the suture hook then can be removed and the free end of the shuttle brought out the same anterior cannula. The eyelet is loaded with the corresponding 9 o’clock STIK suture, which can then be shuttled through the tissue. Once passed, the 9 o’clock STIK suture is stored outside the anterior cannula (Fig. 25-4). The remaining STIK sutures can be passed using the suture hook in the posterior cannula. The suture shuttle is retrieved out the anterior cannula and the corresponding STIK sutures shuttled out the posterior cannula (Fig. 25-5). When passing the remaining STIK sutures, it is critical that each subsequent suture be passed lateral to the previous one. This stay lateral technique is critically important when augmenting a rotator cuff repair. For example, the 11 o’clock STIK is passed with a suture hook, grabbing tissue approximately 1 cm medial to the original repair. The shuttle is retrieved on the lateral side of the 9 o’clock STIK suture. The subsequent three STIK sutures are passed in the same fashion, always staying lateral (Fig. 25-6). A crochet hook is used to retrieve and bring the 9 o’clock suture out the posterior cannula with the other four STIK sutures.

FIGURE 25-4 The 9 o’clock STIK suture is passed using a shuttle through the anterior cannula (arrows).

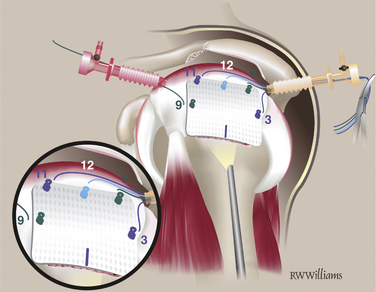

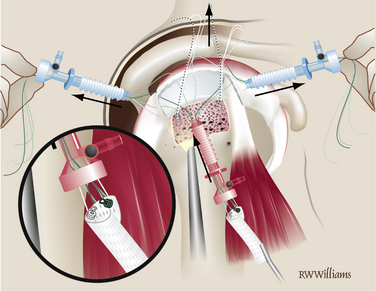

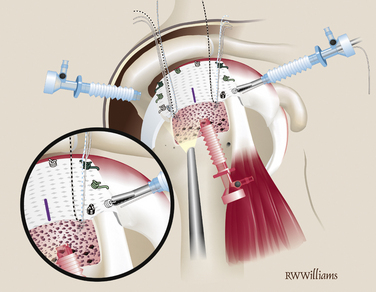

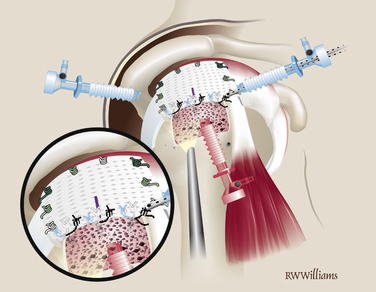

Graft Insertion.

Once the five STIK sutures are passed and clamped out the posterior cannula, the graft is ready to be inserted down the anterior cannula. The graft is carefully rolled on itself with the bursal surface remaining inside so that it will face up when the graft is unrolled in the joint. The graft is inserted with a push-pull technique; the folded graft is carefully pushed down the anterior cannula with an arthroscopic grasper and the five STIK suture ends are pulled from the posterior cannula. With the graft in the joint, each STIK suture can be sequentially tensioned to position the graft over the repair site (Fig. 25-7). Each STIK knot can then be retrieved and tied with a sliding locking knot, followed by three alternating half-hitches to secure the graft anteriorly, medially, and posteriorly.

Lateral Fixation.

Previously, the tuberosity was prepared for the lateral suture anchors. Two anchors are placed 1 cm lateral to the suture line for the primary repair and placed at the 5 and 7 o’clock positions of the unfolded graft. The anchors can be double- or triple-loaded; abduction of the arm is helpful for placement of these more lateral anchors. Simple sutures are passed through the lateral aspect of the graft and tied arthroscopically. The midline mark on the graft is helpful for orienting suture placement for the lateral anchors (Fig. 25-8).

Rotator Cuff Bridging Reconstruction

Graft Preparation.

The anterior, posterior, and lateral edges of the graft are marked with a sterile marking pen. On the medial edge, four to five STIK sutures are placed 3 to 4 mm from the edge. They are placed from top to bottom 5 mm apart, leaving the knotted ends on the top (smooth side) of the graft. Additional STIK sutures are placed in the anterior and posterior edges of the graft in a similar fashion (Fig. 25-9).

Anchor Placement.

Two triple-loaded suture anchors are placed percutaneously into the prepared tuberosity 4 to 5 mm lateral to the edge of cartilage. One is placed just posterior to the biceps and a second just anterior to the posterior cuff remnant. When appropriate, one suture from each anchor is passed through the adjacent cuff and biceps. When the anterior suture is tied, it will effect a tenodesis of the biceps in the bicipital groove (Fig. 25-10).

Posterior Suture Passing.

Place the graft on a moist towel attached to the arm lateral to the lateral cannula and orient the graft so the posterior edge faces the cannula. Pass a suture-shuttling device through the lateral aspect of the posterior cuff remnant. Retrieve it in the lateral cannula, being careful to stay between the two clusters of sutures from the anchors. The unknotted end of the posterior lateral STIK suture tie is shuttled out the posterior cannula (Fig. 25-11). Working from lateral to medial, the remaining posterior STIK sutures are passed in similar fashion. The shuttle device is always retrieved into the lateral cannula anterior to the previously passed suture to avoid entanglement.

Corner Suture Passing.

With the anterior graft edge still facing the cannula, retrieve the most anterior suture in the anterior anchor out the lateral cannula and pass it through the graft from bottom to top at the anterior lateral corner using a Keith needle. Tie a STIK knot on the upper end of the suture. Rotate the graft so that the posterior edge faces the cannula. Retrieve the most posterior suture from the posterior anchor, pass it through the posterior lateral corner of the graft, and tie a STIK knot on top (Fig. 25-12).

Graft Insertion.

Rotate the graft so the medial border faces the cannula and roll it up. Advance the graft through the cannula into the shoulder by pulling on the free ends of the STIK sutures and pushing the graft with a small arthroscopic clamp (Fig. 25-13). Once in the shoulder, pull the slack from all STIK sutures, allowing it to flatten in the cuff defect.

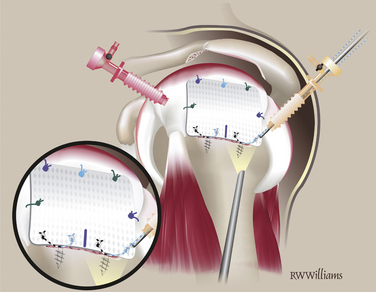

Tie STIK Sutures.

Begin tying from posterior to anterior. Retrieve the free ends of all STIK sutures except the most posterior one out the anterior cannula. Retrieve the free and knotted end of the most posterior STIK suture out the posterior cannula and tie it. Continue tying around the posterior, medial, and anterior edges of the graft and then tie the two STIK sutures passed from the anchors (Fig. 25-14).

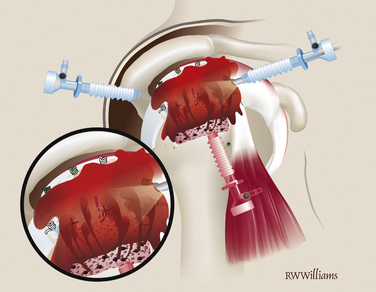

Lateral Fixation.

Pass and tie the remaining sutures from the anchors on the lateral edge. Insert additional anchors and pass simple sutures as needed (Fig. 25-15). At the completion of the procedure, turn off the arthroscopic pump and observe the bone marrow as it flows from the vents on the tuberosity, forming a red blanket over the graft—the “crimson duvet” (Fig. 25-16).

FIGURE 25-15 Anchored sutures are passed and tied in simple fashion. Additional anchors are placed if needed.

FIGURE 25-16 The arthroscopic pump is turned off, allowing the “crimson duvet” to blanket the graft.

PEARLS& PITFALLS

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

More than 80 procedures have been performed at SCOI to date, with very few complications. There has only been one infection in an immunocompromised patient that responded to arthroscopic irrigation, débridement, and antibiotics. The graft itself is acellular, eliminating the possibility of graft rejection. Recently, 2-year follow-up data became available for the first 13 patients treated with GRAFTJACKET bridging technique at our institution.32 Of the 13 patients, 12 were satisfied with their results. Postoperatively, the Constant scores increased to 87.3 from 53.8 preoperatively (P = .0001). The mean modified UCLA score increased to 29.8 from 18.4 (P = .0001). MRI data is also convincing; 12 of 13 patients demonstrated full incorporation of the graft into native tissue at 1 year.32 Currently, a multicenter prospective randomized study is in progress to study GRAFTJACKET allograft augmentation of rotator cuff repairs; however, 2-year follow-up data are not yet available.

1. Barber FA, Herbert MA, Coons DA Tendon augmentation grafts: biomechanical failure loads and failure patterns. Arthroscopy, 22; 2006:534-538.

2. Malcarney HL, Bonar F, Murrell GA Early inflammatory reaction after rotator cuff repair with a porcine small intestine submucosal implant: a report of 4 cases. Am J Sports Med, 33; 2005:907-911.

3. Sclamberg SG, Tibone JE, Itamura JM, Kasraeian S. Six-month magnetic resonance imaging follow-up of large and massive rotator cuff repairs reinforced with porcine small intestinal submucosa. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13:538-541.

4. Walton JR, Bowman NK, Khatib Y, et al Restore orthobiologic implant: not recommended for augmentation of rotator cuff repairs. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 89; 2007:786-791.

5. Seldes RM, Abramchayev I. Arthroscopic insertion of a biologic rotator cuff tissue augmentation after rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:113-116.

6. Belcher HJ, Zic R Adverse effect of porcine collagen interposition after trapeziectomy: a comparative study. J Hand Surg [Br], 26; 2001:159-164.

7. Badhe SP, Lawrence TM, Smith FD, Lunn PG. An assessment of porcine dermal xenograft as an augmentation graft in the treatment of extensive rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(suppl):35S-39S.

8. Soler JA, Gidwani S, Curtis MJ. Early complications from the use of porcine dermal collagen implants (Permacol) as bridging constructs in the repair of massive rotator cuff tears. A report of 4 cases. Acta Orthop Belg. 2007;73:432-436.

9. Audenaert E, Van Nuffel J, Schepens A, et al Reconstruction of massive rotator cuff lesions with a synthetic interposition graft: a prospective study of 41 patients. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc, 14; 2006:360-364.

10. Ozaki J, Fujimoto S, Masuhara K, et al. Reconstruction of chronic massive rotator cuff tears with synthetic materials. Clin Orthop Relat Res.. 1986;202:173-183.

11. Kimura A, Okamura K, Fukushima S, et al. Clinical results of rotator cuff reconstruction with PTFE felt augmentation for irreparable massive rotator cuff tears. Shoulder Joint. 2000;24:485-488.

12. Hirooka A, Yoneda M, Wakaitani S, et al. Augmentation with a Gore-Tex patch for repair of large rotator cuff tears that cannot be sutured. J Orthop Sci. 2002;7:451-456.

13. Liljensten E, Gisselfalt K, Edberg B, et al. Studies of polyurethane urea bands for ACL reconstruction. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2002;13:351-359.

14. Neviaser JS, Neviaser RJ, Neviaser TJ. The repair of chronic massive ruptures of the rotator cuff of the shoulder by use of a freeze-dried rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60:681-684.

15. Nasca RJ. The use of freeze-dried allografts in the management of global rotator cuff tears. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;228:218-226.

16. Fini M, Torricelli P, Giavaresi G, et al. In vitro study comparing two collageneous membranes in view of their clinical application for rotator cuff tendon regeneration. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:98-107.

17. Barber FA, Herbert MA, Boothby MH. Ultimate tensile failure loads of a human dermal allograft rotator cuff augmentation. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:20-24.

18. Ide J, Kikukawa K, Hirose J, et al. Reconstruction of large rotator-cuff tears with acellular dermal matrix grafts in rats. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18:288-295.

19. Adams JE, Zobitz ME, Reach JSJr, et al Rotator cuff repair using an acellular dermal matrix graft: an in vivo study in a canine model. Arthroscopy, 22; 2006:700-709.

20. Romeo AA, Turner TM, Urban RM, et al. Repair of a rotator cuff tendon defect using an acellular human dermal graft in a large primate model. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:e24-e25.

21. Snyder SJ, Arnoczky SP, Bond JL, Dopirak R. Histologic evaluation of a biopsy specimen obtained 3 months after rotator cuff augmentation with graftjacket matrix. Arthroscopy. 2009;25:329-333.

22. Snyder S, Bond J. Technique for arthroscopic replacement of severely damaged rotator cuff using “Graftjacket” allograft. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2007;15:86-94.

23. Labbe MR. Arthroscopic technique for patch augmentation of rotator cuff repairs. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:1136.

24. Dopirak R, Bond J, Snyder S. Arthroscopic total rotator cuff replacement with an acellular human dermal allograft matrix. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2007;1:7-15.

25. Burkhead W, Schiffern S, Krishnan S. Use of Graft Jacket as an augmentation for massive rotator cuff tears. Semin Arthroplasty. 2007;18:11-18.

26. Bond JL, Dopirak RM, Higgins J, et al Arthroscopic replacement of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears using a GraftJacket allograft: technique and preliminary results. Arthroscopy, 24; 2008:403-409.

27. Birmingham PM, Neviaser RJ. Outcome of latissimus dorsi transfer as a salvage procedure for failed rotator cuff repair with loss of elevation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:871-874.

28. Gerber C, Macquieira G, Espinosa N. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:113-120.

29. Cuff D, Pupello D, Virani N, et al. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of rotator cuff deficiency. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1244-1251.

30. Safran O, Iannotti JP. Arthrodesis of the shoulder. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14:145-153.

31. Kovacevic D, Rodeo SA. Biological augmentation of rotator cuff tendon repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:622-633.

32. Burns JP, Snyder SJ. Biologic patches for augmentation of irreparable rotator cuff tears. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;10:11-21.