Biochemistry in the elderly

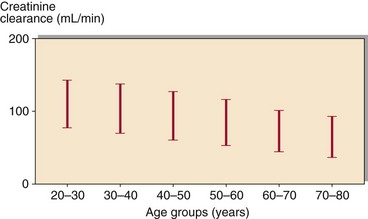

There is considerable variation in the onset of functional changes in body systems because of age. Many organs show a gradual decline in function even in the absence of diseases; but since there is often considerable functional reserve, there are no clinical consequences. The problem facing the clinical biochemist is how to differentiate between the biochemical and physiological changes that are the consequences of ageing, and those factors that indicate disease is present. Just because the result of a biochemistry test in an elderly patient is different from that in a young person does not mean some pathology is present. Serum creatinine is an example. Renal function deteriorates with age (Fig 74.1) but finding a serum creatinine of 140 µmol/L in an 80-year-old woman should not be cause for alarm. Indeed, this creatinine result may represent a remarkably good glomerular filtration rate considering the age of the patient.

Disease in old age

The admission of a patient for geriatric assessment involves a degree of ‘screening’ biochemistry that may point towards the presence of disorders that may not be suspected (Table 74.1).

Table 74.1

Biochemical assessment in a geriatric patient

| Test | Associated conditions |

| Potassium | Hypokalaemia |

| Urea and creatinine | Renal disease |

| Calcium, phosphate and alkaline phosphatase | Bone disease |

| Total protein, albumin | Nutritional state |

| Glucose | Diabetes mellitus |

| Thyroid function tests | Hypothyroidism |

| Haematological investigation and faecal occult blood | Blood and bleeding disorders |

Thyroid disease

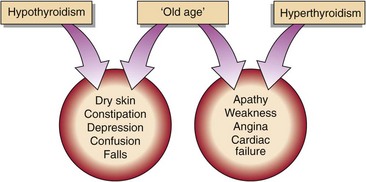

Thyroid dysfunction is common in the elderly. Diagnosis may be overlooked since many of the clinical manifestations of thyroid disease may be misinterpreted as just the normal ageing process (Fig 74.2). Unusual presentations are common, e.g. elderly patients with hyperthyroidism are more likely than younger patients to present with the cardiac-related effects of increased thyroid hormone.

Fig 74.2 The clinical manifestations of thyroid disease may be misinterpreted as characteristics of ‘normal’ ageing.

The interpretation of TSH, T4 and T3 results may not be straightforward in the elderly population as these patients usually have more than one active disease process. A patient with a severe non-thyroidal illness may show low T4, T3 and TSH (p. 91). A patient’s thyroid function can only be satisfactorily investigated in the absence of non-thyroidal illness. Elderly patients may also be taking drugs that affect thyroid function (Table 74.2).

Table 74.2

Some common drugs known to affect thyroid action

| Effect | Drugs |

| Increase TBG | Oestrogens |

| Decrease TBG | Androgens, glucocorticoids |

| Inhibit TBG binding | Phenytoin, salicylates |

| Suppress TSH | L-DOPA, glucocorticoids |

| Inhibit T4 secretion | Lithium |

| Inhibit T4–T3 conversion | Amiodarone, propranolol |

| Reduce oral T4 absorption | Colestyramine, colestipol |

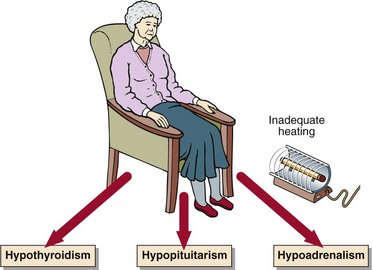

Hypothermia is often encountered in an elderly patient. It is important to establish if there is an underlying endocrine disorder such as thyroid disease, or even adrenal or pituitary hypofunction (Fig 74.3).

Diabetes mellitus

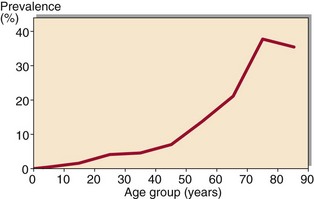

Diabetes mellitus is common in old age (Fig 74.4). Genetic factors and obesity contribute to the insulin resistance that underlies the development of NIDDM (pp. 62–63).

Bone disease

Bone disease in general is more common in elderly patients than in the young. Osteoporosis is the most common bone disease that occurs in the elderly (p. 78). The risk of hip fracture increases dramatically with increasing age because of a reduction in bone mass per unit volume. Bone loss accelerates when oestrogen production falls after the menopause in women, but both sexes show a gradual bone loss throughout life. The common biochemical indices of calcium metabolism are normal in patients even with severe primary osteoporosis, and currently are of little help in diagnosis and treatment, except to ensure that other complicating conditions are not present.