12 Bio-Alcamid®

Summary and Key Features

• Bio-Alcamid® is an acrylic acid-derived, synthetic permanent gel used for soft tissue augmentation

• Bio-Alcamid® quickly gained widespread popularity for the correction of large-volume defects

• Short-term infectious complications are probably physician related

• Long-term inflammatory / infectious complications are significant and may be product related

• Long-term dislocation is product related and strongly suggests structural instability over time

• Correct treatment of all complications is very important and the best method is aggressive removal of the product

Introduction

Following further research to improve biocompatibility, of which the company never released any detail, the product was changed again in 2001, the new name being Bio-Alcamid®. This was a non-biodegradable, biocompatible synthetic polymeric transparent gel with a reticulated structure derived from acrylic acid, containing 4% alkyl-amide-imide groups and 96% apyrogenic water (Fig. 12.1). In 2001, Bio-Alcamid® obtained a Conformité Européenne (CE) certificate, the only requirement in Europe for approval of an injectable filler. It was produced in three different forms of increasing density, i.e. lips, face, and body. The indications remained the same as for Formacryl / Bio-Formacryl®, and again no limits were established in terms of injectable volumes per patient. Bio-Alcamid® correction of large-volume deficiencies such as those caused by pectus excavatum, Poland and Parry–Romberg syndromes and HIV drug-induced lipodystrophy quickly became popular. The patients tolerated the injections well and the clinical results seemed very satisfactory. The material was seen as a valid alternative to lipostructure because of the more predictable results that it offered. The reports in the early literature were extremely good (e.g. those by Pacini et al, Protopapa et al, Terenzi et al, and Casavantes).

Complications of Bio-Alcamid®

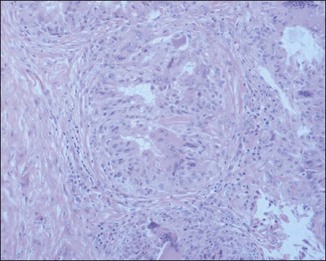

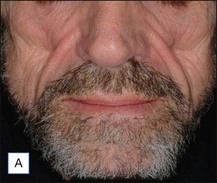

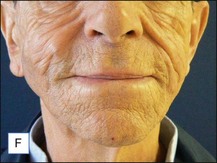

The bacterial biofilm theory has strong supporters. In this concept, a subclinical infection is produced by bacteria that were silently coating the implant ever since the time of injection. This behaves like a time-bomb that can induce a capsular contracture, such as in breast augmentation, or a frankly acute clinical infection, as reported by Christensen. Biopsies taken from Bio-Alcamid® injection sites, however, show typical granulomatous foreign body reactions with giant cells and histiocytes; there is possibly also a host immunologic response (Fig. 12.2). At times, these granulomas become very superficial and are clearly visible at the skin surface, appearing as hard, nodular formations (Fig. 12.3).

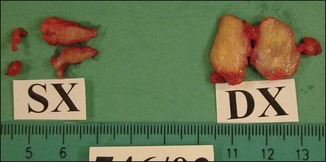

Figure 12.3 Superficial nodules excised bilaterally from the zygomatic region following Bio-Alcamid® injection.

Treatment of acute complications, early or late, inflammatory or infective, should be the same. Antibiotics are mandatory more for medicolegal than for clinical reasons. Their main role is to prevent systemic spread of a possible infection, but it is very unlikely that they will be able to solve the problem on their own. Aggressive evacuation of the material is the mainstay of treatment, and the sooner it is done the better. This can be achieved by squeezing thoroughly the area containing the product after making a stab wound incision in the overlying skin with a no. 11 blade (Figs 12.4 and 12.5). The product at this time appears very different from the original: the color is deep yellow and the texture often granular. Cultures from the extracted material are often sterile, but may also contain bacteria of various species. After evacuation, the pocket should be briskly irrigated. Povidone-iodine 10% solution is fine for disinfection, and 10% hydrogen peroxide is helpful to wash out the material. Both should be used in sequence, and saline for the final irrigations. An irrigation system kept in situ has been advocated by Goldan and colleagues, allowing multiple irrigations each day with good results. This, however, requires hospitalization, with significant expenses and patient inconvenience.

Figure 12.4 Acute reaction of right forearm 6 years after Bio-Alcamid® injection to correct obstetric palsy hypoplasia.

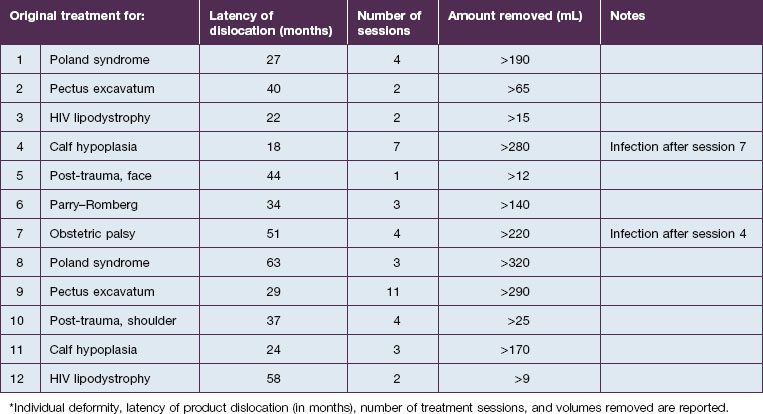

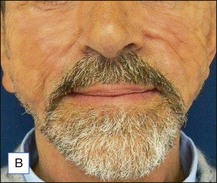

An entirely different type of late complication that we have observed is expansion and gravitational dislocation of the material. In our experience this was seen in 12 patients, 18–63 months after large-volume implantations. The data are summarized in Table 12.1. All of them had been treated for significant soft tissue defects, and the volumes injected had ranged from 12 to 320 mL in multiple sessions. They unanimously reported that early results had been extremely satisfactory, with adequate volume restoration, very good shape, and an extremely natural, soft ‘feel’. However, at variable intervals after the treatment, the patients noticed a progressive expansion and descent of the material, which also became more superficial. The typical appearance was that of externally projecting subcutaneous masses. With digital pressure these tumefactions feel extremely soft, almost fluctuating. The obvious treatment of this complication is the evacuation of the product, which seems to be a reasonably simple task. Indeed, the Bio-Alcamid® can be easily aspirated through a 14/16-gauge needle, or squeezed through a no. 11 blade buttonhole incision. Without too much effort, the fluid collection is quickly removed and the deformity disappears. The cavity is then thoroughly washed with 10% povidone–iodine solution, hydrogen peroxide and saline, and mild pressure is applied. As in acute reactions, the aspirated material looks very different from the original viscous, transparent gel. Once again, the color is deep yellow, but it is also much more fluid.

Unfortunately, this apparently brilliant solution was too often only the beginning of a true ordeal. Most of these patients came back with total or partial recurrence of the deformity (Fig. 12.6). They responded to repeated treatment just as well as they did the first time, with what seemed to be once again total evacuation of the material and complete resolution of the deformity. But again, the problem recurred in several patients. We then calculated the total volume of the evacuated fluids from every patient, and found to our surprise that it was often far more than the actual amount of Bio-Alcamid® that had been injected in the first place (Fig. 12.5). Laboratory analysis of the collected fluids evidenced extremely high serum protein contents. This accounted for the deep-yellow color of the transformed Bio-Alcamid®, and also gave a possible explanation for the recurrent deformity. We believe that the proteins that bind to the product over time produce a significant osmotic gradient, hence the ability of the residual amounts of Bio-Alcamid® to bind more extracellular fluids and to reproduce the complication. In our experience, total removal of the material in these cases has been unlikely in just one or two sessions.

A 25-year-old male had been injected with an unreported amount of Bio-Alcamid® on a yearly basis over the previous 6 years for calf augmentation. The final result was significantly overcorrected, and two volume reductions were performed by the physician. Three weeks after the second attempt the patient developed pain, redness, and induration. At that time the injecting physician, who was out of town, referred the patient to us. Evacuation of the product was performed the same day; however, local inflammation was significant, tissues were extremely firm, and the material drained was partially purulent. It was immediately obvious that in spite of multiple accesses it was not possible to remove it all. Cultures grew Staphylococcus epidermidis, and antibiotic treatment was undertaken. Chronic inflammation and spontaneous fistulas followed. Months later the patient suffered two more episodes of acute infection, and both times surgical debridement of the residual pockets was performed with little success. A year after the onset of the problem the fistulas have finally closed, but the tissues remain extremely hard, and the scars and the deformity very obvious (Fig. 12.7).

Alijotas-Reig A, Garcia-Gimenez V. Delayed immune-mediated adverse effects of polyalkylimide dermal fillers. Clinical findings and long-term follow-up. Archives of Dermatology. 2008;144:637–642.

Casavantes LC. Biopolimero polialquilimida (BioAlcamid), material de relleno de alto volumen para la reconstruccion facial en pacientes con lipoatrofia asociada a VIH. Presentacion de 100 casos. Dermatologia. 2004;2:226–233.

Christensen L. Normal and pathologic tissue reactions to soft tissue gel fillers. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;33(s2):S168–S175.

Goldan O, Georgiou I, Grabov-Nardini G. Early and late complications after a nonabsorbable hydrogel polymer injection: a series of 14 patients and novel management. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;33:S199–S206.

Jones DH, Carruthers A, Fitzgerald R, et al. Late-appearing abscesses after injections of nonabsorbable hydrogel polymer for HIV-associated facial lipoatrophy. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;33(2):193–198.

Karim RB, Hage JJ, van Rozelaar L, et al. Complications of polyalkylimide 4% injections (Bio-Alcamid): a report of 18 cases. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery. 2006;59:1409–1414.

Lafarge Claoue B, Rabineau P. The polyalkylimide gel. Experience with Bio-Alcamid. Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 2004;23:236–240.

Lemperle G, Gauthier-Hazan N, Wolters M, et al. Foreign body granulomas after all injectable dermal fillers: part 1. Possible causes. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2009;123(6):1842–1863.

Nelson L, Stewart KJ. Early and late complications of polyalkylamide gel (Bio-Alcamid(r)). Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery. 2011;64(3):401–404.

Pacini S, Ruggiero M, Cammarota N, et al. Bio-Alcamid, a novel prosthetic polymer, does not interfere with morphological and functional characteristics of human skin fibroblasts. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2003;111(1):489–491.

Protopapa C, Sito G, Caporale D, et al. Bio-Alcamid in drug-induced lipodystrophy. Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy. 2003;5:226–230.

Ross AH, Malhotra R. Long-term orbitofacial complications of polyalkylimide 4% (Bio-Alcamid). Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2009;25(5):394–397.

Schelke LW, van den Elzen HJ, Canninga M, et al. Complications after treatment with polyalkylimide. Dermatologic Surgery. 2009;35(2):1625–1628.

Tamir G, Ohad R, Metanes I, et al. Giant multi-lobulated mucous cyst of the right face following soft tissue augmentation with Bio-Alcamid. European Journal of Plastic Surgery. 2011. Online.

Terenzi V, Leonardi A, Covelli E, et al. Parry-Romberg syndrome. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2005;116(5):e97–e102.

Treacy PJ, Goldberg DJ. Use of a biopolymer polyalkylimide filler for facial lipodystrophy in HIV-positive patients undergoing treatment with antiretroviral drugs. Dermatologic Surgery. 2006;32(6):804–808.