Binder Syndrome

Evaluation and Treatment

In 1939, Noyes first described a patient whose face was characterized by a flat nasal tip and a retruded maxillary–nasal base.32 He did not recognize this as an entity unique from other known forms of maxillary retrusion. It was not until 1962 that von Binder came to recognize the specific entity of nasomaxillary hypoplasia that is now called Binder syndrome.53 He described physical findings of nasomaxillary hypoplasia, a convex lip, a vertical (short) nose, a flat frontonasal angle, an absent anterior nasal spine, limited nasal mucosa, and hypoplastic frontal sinuses. von Binder postulated that the hypoplasia was the result of a disturbance of the prosencephalic induction center at a critical phase during development. In 1989, Sheffield and colleagues reviewed 103 cases of chondrodysplasia punctata (CDP) seen in Melbourne, Australia, over a 20-year period.48 They concluded that Binder syndrome should be classified as a mild form of CDP. In 1991, Sheffield and colleagues pointed out that most patients with Binder syndrome seek medical attention during adolescence.47 By this age, the confirmatory diagnostic radiologic features of CDP have disappeared, so the diagnosis of CDP is often not considered. Older patients may show terminal phalangeal hypoplasia of the hand and variable anomalies of the vertebrae (i.e., vertebral clefting). Associated malformations of the cervical spine primarily affect the atlas and the axis without known clinical sequelae.35,43 Familial recurrence has been reported, and inheritance may occur as an autosomal recessive trait with incomplete penetrance.34 The syndrome may also be of a threshold character with a genetically multifactorial background.5,14,45

The physical findings of Binder syndrome result from hypoplasia of the anterior nasal floor (fossa praenasalis), and the anterior maxilla including the pyriform rim region.26,33 When viewing the nose–upper lip complex from the worm’s-eye perspective, typical variations from normal are described as a retracted columella–lip junction, a lack of normal triangular flare at the nasal base, a perpendicular alar–cheek junction, a convex flat nasal tip with a wide and shallow philtrum, crescent-shaped nostrils without a distinct sill, and a stretched and shallow cupid’s bow.27,41 Striking profile characteristics of the nose include vertical shortening of the columella, a lack of tip projection, perialar flattening, and an acute nasolabial angle.11,28 The dentition and occlusion in an untreated individual will typically demonstrate the proclination of the maxillary incisors, “peg” laterals, and a canine Angle class III negative overjet tendency.21

Anthropometric explanations for these findings were first suggested by Zuckerkandl in 1882, when he described an anomaly in the anterior nasal floor in which the normal crest that separates the nasal floor from the anterior surface of the maxilla was absent.56 Instead, a small pit—the fossa praenasalis—constituted the pyriform aperture.18,24 Other investigators have pointed out that the premaxilla of normal Caucasian individuals is incorporated into the upper arch.2,3 This results in a prominence or projection of the base of the nose. By contrast, when the premaxilla (i.e., the primary palate) is not incorporated into the arch (i.e., in higher primates, certain racial groups, persons with Binder syndrome, and individuals with bilateral clefted alveolar ridges and lips), there will be flattening of the premaxillary region and of the base of the nose.6 This is more commonly seen among African and Asian people.10

In an attempt to reconstruct the skeletal deformities associated with Binder syndrome, clinicians have suggested a spectrum of procedures, including Le Fort I osteotomy, Le Fort II osteotomy, Le Fort III osteotomy, and a combination of Le Fort I and II osteotomies.4,8,12,17,19,20,22,23,31,36,39,42,44,49,51,55 Augmentation of the infraorbital rims, the pyriform rims (paranasal), and the anterior maxilla with the use of a spectrum of materials have all been tried.7,25,40,50 Suggested nasal reconstructive options have included autogenous, homogenous, and allogenic bone and cartilage grafts that extend up the columella (i.e., from the base of the maxilla to the nasal tip) and over the nasal dorsum (i.e., from the radix to the tip).1,9,13,15,19,29,30,38,39,46,52 Suggested soft-tissue procedures include septal cartilage and mucosal flaps, upper lip to nasal skin flaps to lengthen the columella, and a variety of subcutaneous augmentation procedures and fillers.37,54 Compensating orthodontic or dental restorative work may also be undertaken.

With Binder syndrome, a degree of hypoplasia of the premaxilla and of the quadrangular cartilage of the nasal septum is a consistent finding. This author agrees with Holmstrom and colleagues that, with this anomaly, there is a local shortage of bone in the premaxillary region and an absence of cartilage in the anterior septum.18–20 However, as Tessier pointed out, there is no significant shortage of soft tissue available.50–51 Furthermore, modification of the uninvolved orbits, zygomas, and upper nasal dorsum (i.e., the nasal bones) is rarely indicated or advantageous. The observed facial features in an individual with Binder syndrome are dependent on the degree of hypoplasia of the anterior nasal floor (fossa paranasalis) present at the time of birth. The deformities are believed to be non-progressive with age.

Current Approach to Reconstruction

The approach to the correction of the Binder syndrome deformity is to plan for a staged reconstruction to coincide with facial and dental growth patterns and psychosocial needs.16,39 An analysis of each patient’s morphology is followed by a review of the reconstructive options with the patient and family. The most gratifying long-term functions (i.e., occlusion and breathing) and facial aesthetics are generally achieved when carrying out the reconstruction after the completion of growth and before the individual’s graduation from high school (Fig. 29-1 through 29-5). Orthodontic treatment should be coordinated with consideration of orthognathic correction and premaxillary augmentation to be followed by definitive nasal reconstruction. The ideal orthodontic treatment often includes maxillary first bicuspid extractions with retraction and alignment of the anterior teeth to produce ideal incisor inclination within solid basal bone. Unfortunately, many individuals with Binder syndrome will have already been treated with an orthodontic camouflage approach. During the process, the maxillary incisors are tipped facially, and the mandibular incisors are often retroclined. This will typically achieve successful neutralization of the occlusion (i.e., the correction of overjet), but it will leave the patient looking as if he or she has a maxillary deficiency. Attempts at surgical augmentation after orthodontic camouflage are generally suboptimal. When indicated, definitive orthognathic reconstruction is planned to idealize the vertical, transverse, and horizontal midface proportions. A Le Fort I osteotomy (horizontal advancement and a variable degree of vertical lengthening) is frequently combined with an osseous genioplasty (vertical shortening and horizontal advancement). Sagittal split ramus osteotomies are often needed to avoid the limitations inherent to mandibular autorotation. Further reconstruction involves the application of a crafted bone graft to the deficient premaxillary and pyriform rim regions. This is best accomplished simultaneously with the orthognathic procedures.

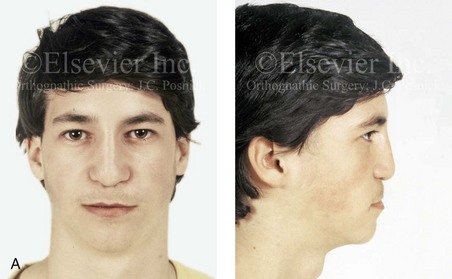

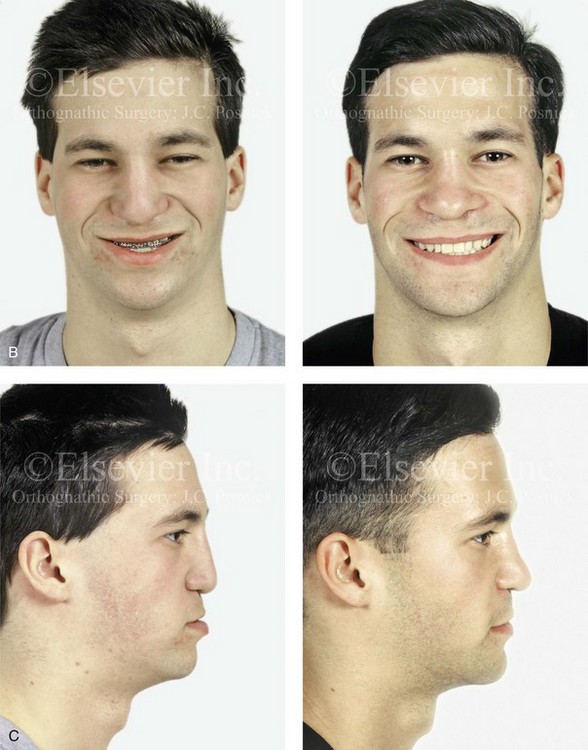

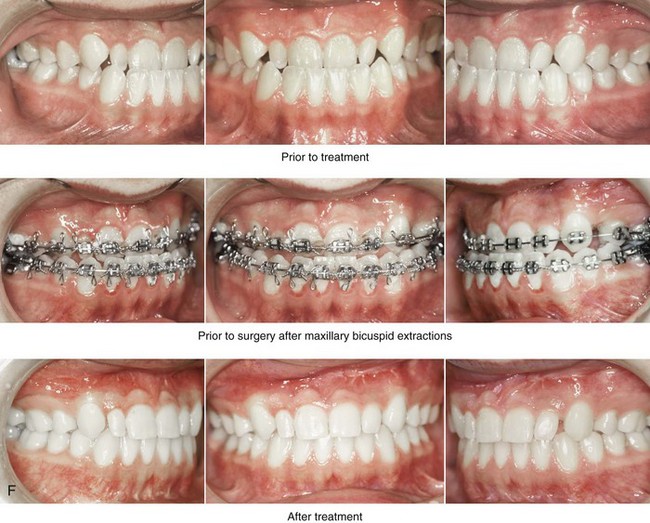

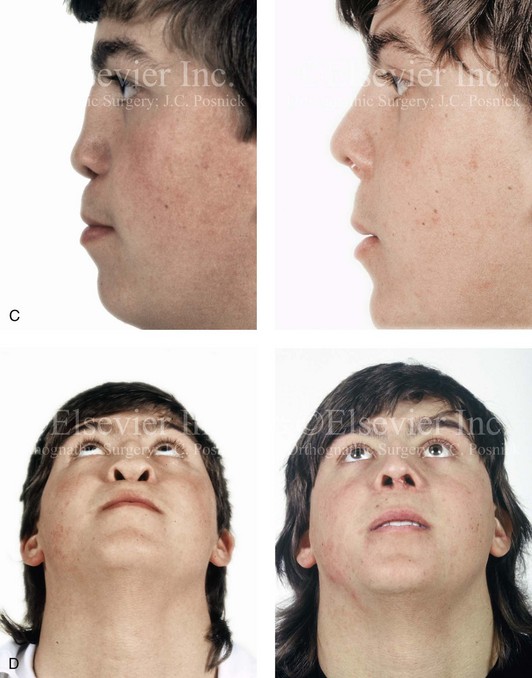

Figure 29-1 A 17-year-old boy, who was born with Binder syndrome was referred by his orthodontist for surgical evaluation. When he was 7 years old he underwent nasal augmentation with Silastic implants with another surgeon. Orthodontic treatment including maxillary first-bicuspid extractions and orthognathic and nasal surgery was chosen. The patient’s procedures included a Le Fort I osteotomy (horizontal advancement); the removal of nasal implants; osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement); and nasal reconstruction (corticocancellous iliac graft). A, Facial views at 10 years old with Silastic implants in place. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C and D, Profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Worm’s-eye views before and after reconstruction. F, Occlusal views before and after reconstruction. G, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. H, Intraoperative views of removed Silastic nasal implants. The crafted iliac corticocancellous bone graft before inset is also shown. I, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before treatment and after reconstruction. A (right), B, C, F, H, I, From Posnick JC, Tompson B: Binder syndrome: Staging of reconstruction and skeletal stability and relapse patters after Le Fort I osteotomy using miniplate fixation, Plast Reconstr Surg 99:967, 1997.

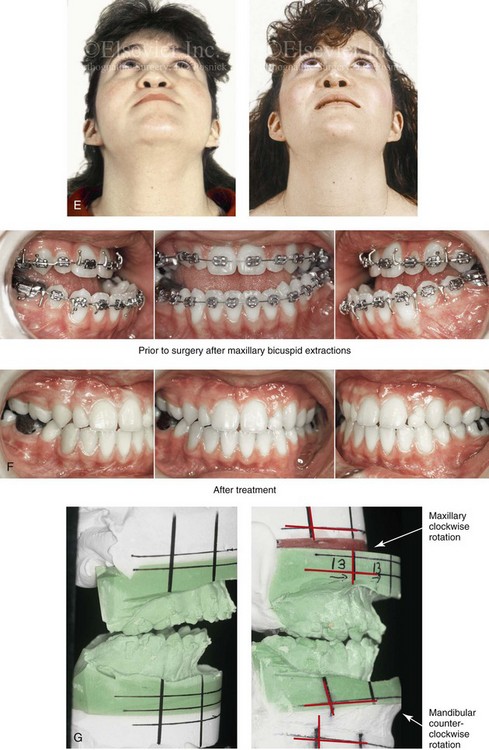

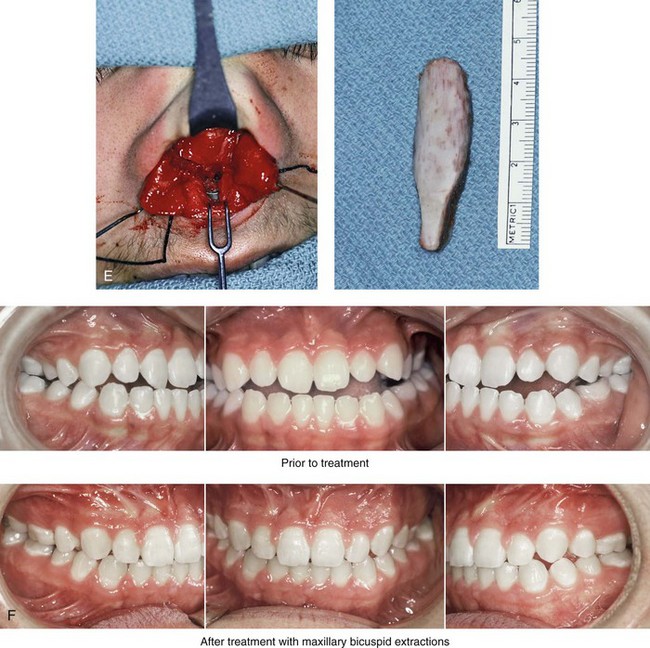

Figure 29-2 A 16-year-old girl who was born with Binder syndrome was referred by her orthodontist for surgical evaluation. She agreed to orthodontic treatment that included maxillary first bicuspid extractions and orthognathic and nasal surgery. The patient’s procedures included Le Fort I osteotomy (horizontal advancement); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies; osseous genioplasty; and nasal reconstruction (autogenous rib graft). A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. D, Profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Worm’s-eye views before and after reconstruction. F, Occlusal views before and after reconstruction. G, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. H, Intraoperative views of open rhinoplasty exposure. The rib bone (dorsal strut) and rib cartilage (caudal strut) grafts are shown before inset. I, Computed tomography scan and intraoperative views that confirm premaxillary hypoplasia consistent with Binder syndrome. J, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction. B, F (top center and bottom center), H, From Posnick JC, Tompson B: Binder syndrome: Staging of reconstruction and skeletal stability and relapse patters after Le Fort I osteotomy using miniplate fixation, Plast Reconstr Surg 99:965, 1997.

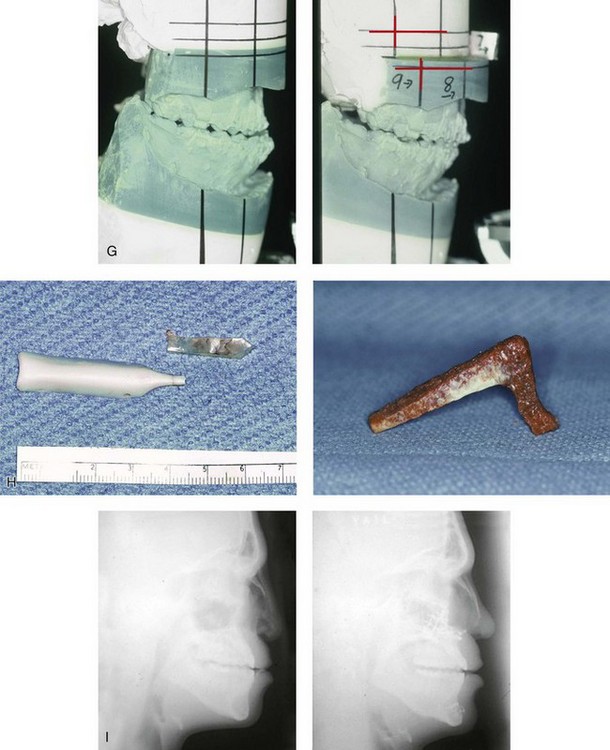

Figure 29-3 A 16-year-old girl who was born with Binder syndrome was referred by her orthodontist for surgical evaluation. She agreed to orthodontic treatment that included maxillary first bicuspid extractions and orthognathic surgery. The patient’s procedures included Le Fort I osteotomy (horizontal advancement); osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement); and nasal reconstruction. The nasal reconstruction (cranial graft) was complicated by pressure necrosis of the nasal tip skin, which necessitated the removal of the distal aspect of the graft. Six months later, through an open rhinoplasty approach, autogenous rib cartilage (a caudal strut) was used to revise the nasal tip. A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Profile views before and after reconstruction. C, Worm’s-eye views before and after reconstruction. D, Occlusal views during orthodontics and after reconstruction. E, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. F, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction.

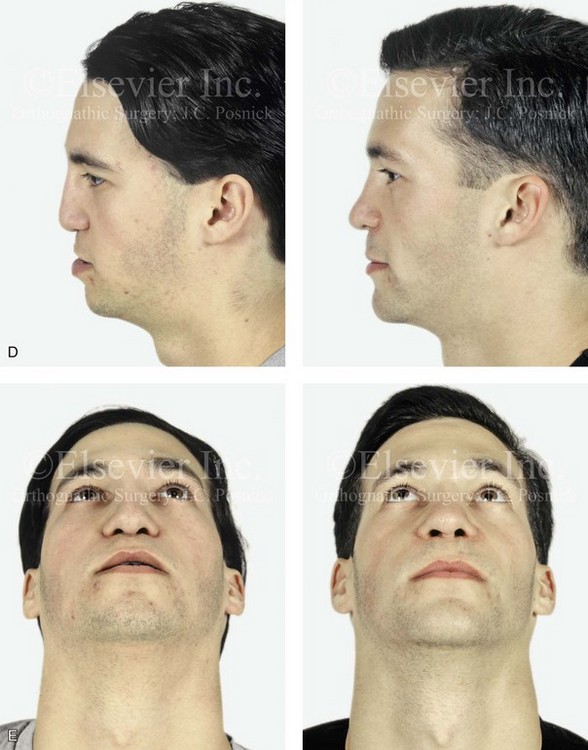

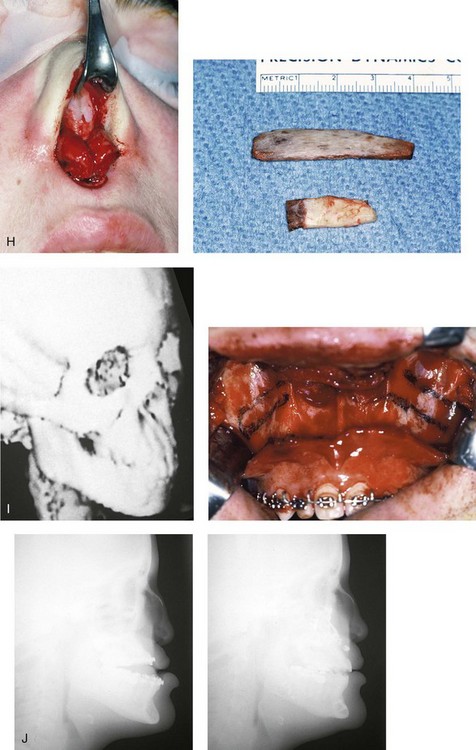

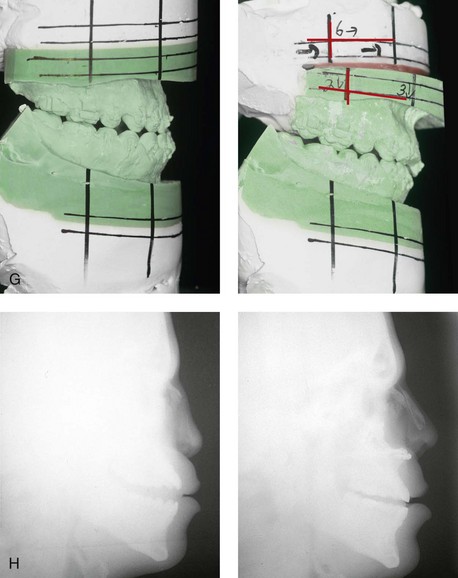

Figure 29-4 A 17-year-old boy who was born with Binder syndrome was referred for surgical evaluation. He agreed to orthodontic treatment that included maxillary first bicuspid extractions and orthognathic and nasal surgery. The patient’s procedures included Le Fort I osteotomy (horizontal advancement) and nasal reconstruction (autogenous rib graft). The nasal reconstruction was carried out through an open (columella splitting) technique. The skin of the columella was stretched but not directly lengthened. Autogenous rib bone (dorsal strut) and rib cartilage (caudal strut) were harvested, crafted, and then inset and secured in place. A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Close-up profile views before and after reconstruction. D, Worm’s-eye views before and after reconstruction. E, Intraoperative views of open rhinoplasty exposure. A Kirschner wire has been inserted into the base of the maxilla. The Kirschner wire extends out of bone. The rib cartilage (caudal strut) will pierce the Kirschner wire and extend to the nasal tip. The crafted rib bone (dorsal strut) is shown before inset. It will join to the caudal graft to form the nasal tip. F, Occlusal views before and after reconstruction. G, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic after model planning. H, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction.

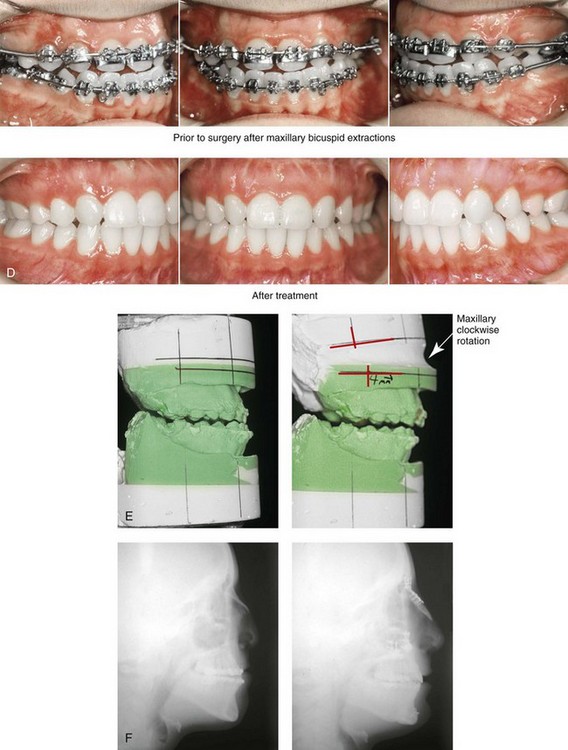

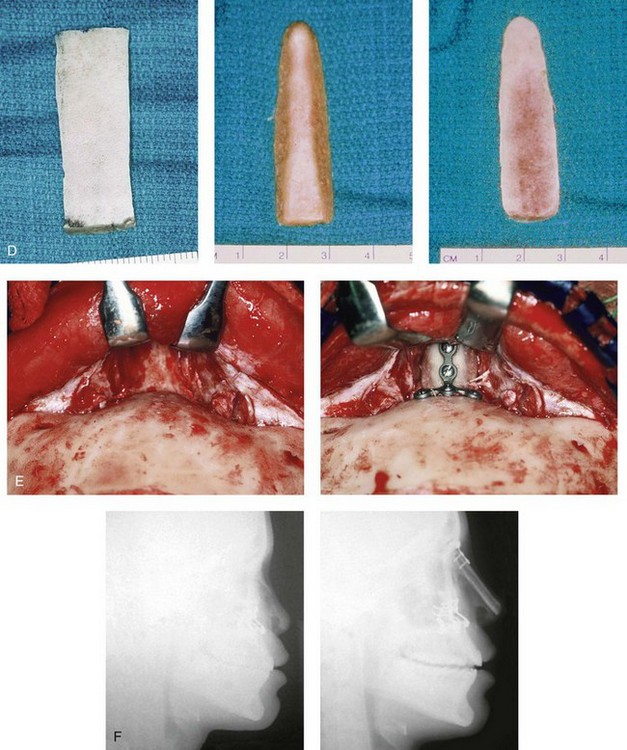

Figure 29-5 A 16-year-old girl who was born with Binder syndrome underwent Le Fort I osteotomy and septal cartilage graft to the dorsum of the nose with another surgeon. A residual nasal deformity remained. She was referred to this surgeon and underwent nasal reconstruction. Through a coronal scalp incision, a full-thickness cranial bone graft was harvested, crafted, and stabilized in place. The graft extended from the radix to the nasal tip. The lower lateral cartilages were then sutured over the top of the graft to form the new nasal tip. A, Close-up profile views before and after nasal reconstruction. B, Close-up frontal views before and after nasal reconstruction. C, Close-up worm’s-eye views before and after nasal reconstruction. D, Harvested full-thickness cranial bone before and after crafting for nasal reconstruction. E, Intraoperative close-up views of the nasofrontal process before and after the placement and stabilization of the cranial bone graft. F, Lateral cephalometric views before and after nasal reconstruction. D, From Posnick JC, Seagle MB, Armstrong D: Nasal reconstruction with full-thickness cranial bone grafts and rigid internal skeletal fixation through a coronal incision, Plast Reconstr Surg 86:894, 1990.

Ideally, the nasal reconstruction is carried out after the orthognathic and anterior maxillary augmentation procedures (see Fig. 1-5).38,39 This is accomplished by reconstructing the cartilaginous nasal deficiency. Stretching of the soft-tissue envelope over the reconstructed underlying nasal cartilage framework is accomplished at wound closure. When first-stage early nasal augmentation was carried out during childhood and before orthognathic correction, some profile improvements maybe achieved, but a relief of the stigma of Binder syndrome is not likely. Early nasal augmentation also imposes limitations on the child’s physical activity to prevent graft fracture or displacement. These restrictions on the daily activities of childhood are likely to be more psychosocially traumatic than the original nasal deformity. For effective reconstruction, all aspects of the deformity should be addressed with a coordinated long-term approach in mind.

Skeletal Stability after Orthognathic Reconstruction

Few authors have looked at the early or late skeletal stability achieved when osteotomies are carried out to correct the Binder syndrome midface deficiency. In a previously published study, Posnick and colleagues prospectively assessed initial and long-term skeletal stability after orthognathic reconstruction including a Le Fort I osteotomy followed by nasal reconstruction in a consecutive series of skeletally mature Caucasian individuals born with Binder syndrome.39

Controversies and Unresolved Issues

The precise genetic cause of Binder syndrome has not yet been confirmed. Gorlin and colleagues suggested that maxillonasal dysplasia was a non-specific abnormality of the nasomaxillary complex.14 Over time, it has become apparent that many patients with Binder syndrome ultimately have a form of chondrodysplasia punctate, although genetic heterogeneity exists. Children with the X-linked recessive for of chondrodysplasia punctate have molecular alterations in the arylsulfatase E gene. Because of the X-linked inheritance pattern, females with this form of chondrodysplasia punctate tend to be much more mildly affected than males. Molecular testing for alterations in arylsulfatase E is clinically available and should be tested for.

In retrospect, the features defined by von Binder were not altogether typical of those found in most patients who are currently categorized as having Binder syndrome. It is also known that frequent ethnic characteristics of both Asian and African individuals are a sloped backward and vertically short anterior maxilla, pyriform rims, and a deficient dorsum of the nose. This results in deficiency of alveolar bone to house the maxillary incisors. The anterior nasal spine is hypoplastic, but it is often present as a small ridge. A lack of height of the dorsum of the nose (i.e., bone and cartilage) with increased width is a frequent ethnic characteristic of Asian and African individuals but not a finding among patients with Binder syndrome. We believe that many patients who are believed to have Binder syndrome more accurately represent ethnic variation. This may well encompass many of the Asian patients described and treated by Goh and Chen in their review of nasal reconstruction for Binder syndrome.13

Holmstrom and others support an orthognathic approach and state that, in a series of Caucasian patients with Binder syndrome (54% of the study group), a majority “suffered a class III malocclusion.”18–20 Although an edge-to-edge incisor relationship may be possible with orthodontics only, it is generally accomplished with excessive maxillary incisor proclination. This camouflage approach does not address the flat midface appearance or the long-term orthodontic retention needs, and it may lead to periodontal sequelae. To correct the maxillary incisor inclination, an alveolar space analysis will confirm the advantage of extracting maxillary first bicuspids in many of these patients. With molar anchorage, the orthodontist is able to retract the anterior teeth into the space created by the bicuspid extractions, and ideal incisor positioning is accomplished. This approach will further unmask the maxillary hypoplasia and allow for an effective horizontal advancement at the Le Fort I level. When this is combined with a premaxillary region crafted bone graft reconstruction, maximum improvement in the perialar and nasal base morphology is also accomplished. An orthodontic camouflage approach should only be carried out with full disclosure to the patient and his or her family.

The aesthetic advantage of a vertical reduction and an advancement osseous genioplasty in the majority of individuals with Binder syndrome likely reflects the longstanding mouth-breathing pattern and its effects on anterior mandibular growth. In three of the seven patients in the study by Posnick and colleagues, bilateral sagittal split osteotomies were also necessary to correct the secondary mandibular dysmorphology or to prevent the inherent shortcomings of mandibular autorotation.39 In none of the patients was the mandible “set back” as a camouflage for maxillary deficiency.39

Holmstrom reviewed the long-term results of nasal reconstruction in a series of patients with Binder syndrome and found overall good results with a variety of techniques.18–20 A review of nasal reconstruction options is listed below. The option selected for a specific patient is dependent on the unique presenting dysmorphology, the potential risks, the patient-specific objectives, and the surgeon’s comfort level with the particular technique.

1. A cranial graft placed through a coronal scalp incision offers ideal access to the nasofrontal region for contouring and graft stabilization (i.e., plates and screws), and it provides excellent bone volume and quality. The lower lateral cartilage is then sutured over the graft at the tip via a columella incision. This approach generally requires craniotomy and a full-thickness graft, depending on the volume of bone required. Unfortunately, it results in a firm nasal tip that has a tendency toward a degree of resorption and that is prone to fracture with trauma. This approach is preferred only for the occasional patient in whom significant reconstruction of the nasofrontal region and augmentation of the bony dorsum is required (see Fig. 29-5).

2. A costochondral (bone and cartilage) graft maybe placed through a columella splitting incision. This results in a relatively “non-firm” nasal tip with limited resorption or risk of warping over time. If the relatively thin and malleable rib graft is placed in a cantilever fashion (i.e., without a columella strut for stabilization), there is a tendency for non-union with the underlying nasal bones and dislocation or fracture after minimal trauma. If the graft extends from the radix, it may also flatten the nasofrontal angle in an unfavorable way. This approach is generally not a first choice (see Fig. 29-1).

3. If a costochondral graft is selected for dorsal reconstruction (as described previously), a separate columella (rib cartilage) strut graft maybe crafted and then secured with sutures to the dorsal costochondral graft at the new nasal tip. Temporary stabilization of the dorsal bone graft component may be accomplished with a transcutaneous K-wire. A second short buried K-wire is placed to stabilize the rib cartilage (caudal strut) at the base of the maxilla (see Fig. 29-2).

4. An anterior iliac (corticocancellous) graft offers another option, but this is only used when extensive bone volume reconstruction is required. It is placed as a crafted L-shaped strut that is stabilized at the base of the premaxilla with titanium plates and screws and over the mid dorsum with percutaneous K-wires. When iliac bone is used at the time of the Le Fort I osteotomy for augmentation of the premaxilla, additional graft may be harvested for simultaneous nasal reconstruction, as described previously. This surgeon has used this combined single-stage approach only in unique and specific circumstances, because very few deformities require upper dorsal reconstruction (see Fig. 29-1). This approach also raises the level of complexity of the procedure by involving the need for sophisticated intraoperative airway management.

5. An L-shaped rib cartilage graft reconstruction has become this author’s preference whenever the Binder deformity allows. With this procedure, it is not necessary to harvest the L-shaped rib cartilage graft in one piece. Rather, two struts (dorsal and columella) are crafted separately and then inset and sutured together to form the new nasal tip. The columella strut graft extends from the base of the maxilla to the nasal tip. It is fixed in place at the base of the maxilla with a buried K-wire (no. 32 threaded) to prevent slippage or movement. The dorsal strut graft extends from the caudal edge of the nasal bones to the new nasal tip, where it is secured to the columella strut graft with the use of non-resorbable suture material. Warping of the cartilage graft can occur, but resorption is not a problem. A separate K-wire (no. 32 threaded) may be inserted through the spine of the dorsal graft before inset to limit the risk of warping. The lower lateral cartilages are sutured over the top of the grafts, and the end result is a flexible nasal tip. This rib cartilage reconstruction option is preferred whenever feasible (see Chapter 34).

For the individual with Binder syndrome, early reconstruction of the dysmorphic nose (i.e., between the ages of 5 and 12 years) to improve tip projection and to encourage self-esteem is technically possible, but the surgeon should proceed with caution. Disadvantages include the need for additional nasal procedures at the completion of growth and after definitive jaw reconstruction. The inherent perioperative risks and expense; the creation of scar tissue within the nasal soft-tissue envelope; and the need for the child to avoid normal school-aged physical activities to prevent graft dislodgement or fracture should also be considered (see Fig. 29-1, A).

References

1. Ahn, J, Honrado, C, Horn, C. Combined silicone and cartilage implants: Augmentation rhinoplasty in Asian patients. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2004; 6:120–123.

2. Ashley-Montagu, MF. The premaxilla in the primates. Q Rev Biol. 1935; 10:32.

3. Ashley-Montagu, MF. The premaxilla in man. J Am Dent Assoc. 1936; 23:2043.

4. Banks, P, Tanner, B. The mask rhinoplasty: A technique for the treatment of Binder syndrome and related disorders. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993; 92:1038.

5. Bütow, KW, Jacobsohn, PV, de Witt, TW. Nasomaxillo-acrodysostosis. S Afr Med J. 1989; 75:5.

6. Callender, GW. The formation and early growth of the bones of the human face. IV. Philos. Trans R Soc Lond Biol. 1869; 159:163.

7. Converse, JM. Restoration of facial contour by bone grafts introduced through the oral cavity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1950; 6:295.

8. Converse, JM, Horowitz, SL, Valauri, AJ, et al. The treatment of nasomaxillary hypoplasia: A new pyramidal naso-orbital maxillary osteotomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1970; 45:527.

9. Draf, W, Bockmuhl, U, Hoffmann, B. Nasal correction in maxillonasal dysplasia (Binder syndrome): A long-term follow-up study. Br J Plast Surg. 2003; 56:199–204.

10. Dwight, T. Fossa praenasalis. Am J Med Sci. 1892; 103:156.

11. Freihofer, HPM, Jr. The lip profile after correction of retromaxillism in cleft and non-cleft patients. J Maxillofac Surg. 1976; 4:136.

12. Freihofer, HPM, Jr. Changes in nasal profile after maxillary advancement in cleft and non-cleft patients. J Maxillofac Surg. 1977; 5:20.

13. Goh, RC, Chen, YR. Surgical management of Binder’s syndrome: Lessons learned. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2010; 34:722–730.

14. Gorlin, RJ, Cohen, MM, Jr., Levin, LS. Syndromes of the head and neck, ed 3. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990.

15. Gunter, JP, Clark, CP, Friedman, RM. Internal stabilization of autogenous rib cartilage grafts in rhinoplasty: A barrier to cartilage warping. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997; 100:161–169.

16. Harper, DC. Children’s attitudes to physical differences among youth from Western and non-Western cultures. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1995; 32:114.

17. Henderson, D, Jackson, IT. Nasomaxillary hypoplasia: The Le Fort II osteotomy. Br J Oral Surg. 1973; 11:77.

18. Holmstrom, H. Clinical and pathologic features of maxillonasal dysplasia (Binder syndrome): Significance of the prenasal fossa on etiology. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986; 78:559–567.

19. Holmstrom, H. Surgical correction of the nose and midface in maxillofacial dysplasia (Binder syndrome). Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986; 78:568.

20. Holmstrom, H, Kahnberg, KE. Surgical approach in severe cases of maxillonasal dysplasia (Binder syndrome). Swed Dent J. 1988; 12:3.

21. Hopkin, GB. Hypoplasia of the middle third of the face associated with congenital absence of the anterior nasal spine, depression of the nasal bones and Angle class III malocclusion. Br J Plast Surg. 1963; 16:146.

22. Horswell, BB, Holmes, AD, Barnett, JS, et al. Maxillonasal dysplasia (Binder syndrome): A critical review and case study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987; 45:114–122.

23. Jackson, IT, Moos, KF, Sharpe, DT. Total surgical management of Binder syndrome. Ann Plast Surg. 1981; 7:25.

24. Kraus, BS, Decker, JD. The prenatal interrelationships of the maxilla and the premaxilla in the facial development of man. Acta Anat (Basel). 1960; 40:278.

25. Losken, HW, Morris, WM. Skull bone grafts in the treatment of maxillonasal dysostosis (Binder syndrome). S Afr J Surg. 1988; 26:90–94.

26. Macalister. The apertura piriformis. J Anat Physiol. 1898; 32:223.

27. McLaughlin, CR. Absence of the septal cartilage with retarded nasal development. Br J Plast Surg. 1949; 2:61.

28. McWilliam, J, Linder-Aronson, S. Hypoplasia of the middle third of the face: A morphological study. Angle Orthod. 1976; 46:260.

29. Millard, DR. Nasal reconstruction with full-thickness cranial bone grafts and rigid internal skeletal fixation through a coronal incision [discussion]. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990; 86:903.

30. Monasterio, FO, Molina, F, McClintock, JS. Nasal correction in Binder syndrome: The evolution of a treatment plan. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1997; 21:299–308.

31. Munro, IR, Sinclair, WJ, Rudd, NL. Maxillonasal dysplasia (Binder syndrome). Plast Reconstr Surg. 1979; 63:657–663.

32. Noyes, FB. Case report. Angle Orthod. 1939; 9:160.

33. Olow-Nordenram, M, Thilander, B. The craniofacial morphology in persons with maxillonasal dysplasia (Binder syndrome). Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989; 95:148.

34. Olow-Nordenram, M, Valentin, J. An etiologic study of maxillonasal dysplasia: Binder syndrome. Scand J Dent Res. 1988; 96:69.

35. Olow-Nordenram, MAK, Rådberg, CT. Maxillo-nasal dysplasia (Binder syndrome) and associated malformations of the cervical spine. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh). 1984; 25:353.

36. Posnick, JC. Binder syndrome: Evaluation and treatment. In: Posnick JC, ed. Craniofacial and maxillofacial surgery in children and young adults. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co; 2000:446–468.

37. Posnick, JC, Goh, RC, Chen, YR. Discussion of) Surgical management of Binder syndrome: Lessons learned. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2010; 34:731–733.

38. Posnick, JC, Seagle, MB, Armstrong, D. Nasal reconstruction with full–thickness cranial bone grafts and rigid internal skeletal fixation through a coronal incision. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990; 86:894.

39. Posnick, JC, Tompson, B. Binder syndrome: Staging of reconstruction and skeletal stability and relapse patterns after Le Fort I osteotomy using miniplate fixation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997; 99(4):961–973.

40. Psillakis, JM, Lapa, F, Spina, V. Surgical correction of midfacial retrusion (nasomaxillary hypoplasia) in the presence of normal dental occlusion. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1973; 51:67.

41. Quarrell, CR. Absence of the septal cartilage with retarded nasal development. Br J Plast Surg. 1949; 2:61.

42. Ragnell, A. Nasomaxillary retroposition in children: Successive reconstruction of the nose: A preliminary report. Nord Med. 1967; 77:847.

43. Resche, F, Tessier, P, Delaire, J, et al. Craniospinal malformations associated with maxillofacial dysostosis (Binder syndrome). Head Neck Surg. 1990; 3:123.

44. Resche, F, Tulasne, JF, Tessier, P, et al. Malformations de la charniere cranio-rachidienne et du rachis cervical associes a la dysplasie maxillo-nasale de Binder. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 1979; 80:83.

45. Rival, JM, Gherga-Negrea, A, Mainard, R, et al. Dysostose maxillo-nasale de Binder. J Genet Hum. 1974; 22:263.

46. Rune, B, Aberg, M. Bone grafts to the nose in Binder syndrome (maxillonasal dysplasia): A follow-up of eleven patients with the use of profile roentgenograms. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998; 101:297–304.

47. Sheffield, LH, Halliday, JL, Jensen, F. Maxillonasal dysplasia (Binder’s syndrome) and chondrodysplasia punctata [letter]. J Med Genet. 1991; 28:503–504.

48. Sheffield, LJ, Halliday, JL, Danks, DM, et al. Clinical, radiological and biochemical classification of chondrodysplasia punctata [abstract]. Am J Hum Genet. 1989; 45(Suppl):A64.

49. Steinhauser, EW. Variations of Le Fort II osteotomies for correction of midfacial deformities. J Maxillofac Surg. 1980; 8:258.

50. Tessier, P. Aesthetic aspects of bone grafting to the face. Clin Plast Surg. 1981; 8:279–301.

51. Tessier, P, Tulasne, JF, Delaire, J, et al. Therapeutic aspects of maxillonasal dysostosis (Binder syndrome). Head Neck Surg. 1981; 3:207.

52. Tham, C, Lai, YL, Weng, CJ, et al. Silicone augmentation rhinoplasty in an Oriental population. Ann Plast Surg. 2005; 54:1–5.

53. Von Binder, KH. Dysostosis maxillo-nasalis, ein arhinencephaler missbildungscomplex. Dtsch Zahnaerztl. 1962; 17:438.

54. Watanabe, T, Matsuo, K. Augmentation with cartilage grafts around the pyriform aperture to improve the midface and profile in Binder syndrome. Ann Plast Surg. 1996; 36:206–211.

55. West, RA. Discussion of) Binder syndrome: Staging of reconstruction and skeletal stability and relapse patterns after Le Fort I osteotomy using miniplate fixation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997; 99:961.

56. Zuckerkandl, E. Fossae praenasales: Normale und pathologische. Anat Nasenhohle. 1882; 1:48.