Bimaxillary Dental Protrusive Growth Patterns with Dentofacial Disharmony

• Orthognathic and Dentoalveolar Surgical Approaches

• Postsurgical Orthodontic Maintenance and Detailing

• Complications, Informed Consent, and Patient Education

• Malocclusion after Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery

• Temporomandibular Disorders: The Effects of Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery

Bimaxillary dental protrusion can occur in any racial group, but facial divergence (i.e., convexity) and lip prominence are strongly influenced by racial and ethnic characteristics.37,67,95,107 Greater degrees of lip and incisor prominence tend to occur in Asians, Africans, and Latinos as compared with Caucasians.68,75 In Caucasian populations, dental protrusion is more common among individuals of Mediterranean background than among those from more northern European regions. The Australian aborigines, who are classified as Caucasoid, have greater degrees of facial and dental protrusion. Etiologic factors that favor bimaxillary dental protrusion with anterior open bite include heredity; paraoral habits (e.g., thumb sucking); and the presence of strong protrusive tongue muscle forces in combination with weak bilabial (lip) forces.103,104,120 The common physical findings include flaccid lips, procumbent maxillary and mandibular incisors, and an anterior open bite.

Drummond compared the facial morphology of Caucasian Americans to that of African Americans.35 He found that Africans more frequently have a protrusive and strong tongue with loose, flaccid lips. These altered forces during growth are known to gradually push the anterior teeth into a procumbent position. The resulting proclination of the teeth in combination with the thickness of the lips make the lower face appear to be more full. Altemus compared the cephalofacial relationships of Caucasian, African, Chinese, Japanese, Navajo Indian, and Australian aboriginal individuals.3 He concluded that the relative straightness of an individual’s facial profile is very much a reflection of the underlying skeletal parts. He also found that, although the upper facial profiles (i.e., the forehead, orbits, and cheekbones) of the varied racial groups appeared to be remarkably similar, the lower facial profiles (i.e., the maxilla, mandible, and chin region) did not. The position of the anterior teeth and lips of African children were found to be more protrusive as compared with those of Caucasians. Sushner studied 100 lateral facial photographs of “attractive” Africans.119 He used the Steiner, Holdaway, and Ricketts cephalometric standards to analyze the “attractive” African facial photographs,53,88 and he concluded that the soft-tissue profiles of the individuals in those photographs were significantly more protrusive than the accepted Caucasian standards. He went on to establish African cephalometric norms. Similar studies completed by Guinn and Connor confirmed that the African soft-tissue profile is more protrusive and significantly different from Caucasian cephalometric norms.5,24,25,50

Peck and Peck set out to determine the public’s concept of beauty as related to the Caucasian profile.94 The authors found that the general public admires a more full face as compared with the accepted cephalometric normative data and clinical orthodontic standards of the day (e.g., four bicuspid extractions with orthodontic retraction). These authors pointed out that the “ultimate source of our aesthetic values should be the people [i.e., public opinion], not just ourselves [i.e., clinicians].” Foster studied facial aesthetic preferences among various groups by using profile silhouettes.44 The evaluators included Africans, Caucasians, and Chinese individuals; art students; general dentists; and orthodontists. The results confirmed a common aesthetic preference for the position of the lips in profile to be within 1 mm to 2 mm of each other. Another finding was that all groups consistently associated fuller lips with a more youthful appearance. Farrow and colleagues attempted to discover what African Americans find attractive about their own profiles.40 The study results found that the preferred aesthetic profile involved slight convexity and more protrusion as compared with standard Caucasian cephalometric norms. A review of the literature confirms that, as a group, African Americans differ from Caucasian Americans with regard to dental, skeletal, and soft-tissue facial parameters.2,31,43,58,122 For both groups, facial convexity is a preferred feature.28,30,76,77,100 However, the question remains: at what point does attractive fullness (i.e., convexity) of the profile become dysmorphic and unattractive?

Distorted vertical and horizontal growth of the maxillomandibular skeleton in association with bimaxillary dental protrusion will result in both facial and dental disharmony.84 This growth pattern may be associated with Class I, Class II, and Class III molar relationships, but it always occurs with mandibular and maxillary incisor procumbency and anterior open-bite malocclusion.5,47,52,85,113,118 Individuals with bimaxillary dental protrusion will also have varying degrees of lip incompetence and mentalis strain; exposure of the anterior teeth in repose and gingival show with smile; and, typically, a dysmorphic chin in profile. If these aspects become excessive, then the diagnosis of an associated dentofacial disharmony is appropriate.109

The generally offered correction of the anterior open-bite malocclusion associated with bimaxillary dental protrusion is the extraction of four premolars followed by the orthodontic retraction of the anterior teeth into the edentulous gaps.6,121,126 This treatment also tends to retract the lips and to reduce facial convexity.33,34,48,72 To determine which individuals also have significant dentofacial (jaw) disharmony and thus will benefit from an orthognathic approach (i.e., the surgical repositioning of the upper and lower jaws), the clinician should assess pretreatment skeletal, dental, and soft-tissue parameters. This includes the following:

• An evaluation of the maxillomandibular skeleton (i.e., horizontal and vertical dimensions)

• An assessment of the dental condition (i.e., incisor inclination, spacing and crowding, the curve of Spee, arch width, overjet, and overbite)

• An evaluation of the soft-tissue static and dynamic position of the lips (i.e., the lip-to-tooth relationship in repose and with smile, the interlabial gap, the degree of mentalis strain with closure, and the nasolabial and labiomental angles).

Functional Aspects

• Wide lip separation with excessive effort required to achieve lip seal is present.

• Chronic obstructive nasal breathing as a result of increased intranasal airway resistance is frequent (see Chapter 10).

• Classic articulation errors in speech caused by the anterior open-bite malocclusion are expected (see Chapter 8).

• Chewing and swallowing difficulties as a result of the anterior open-bite malocclusion and lip incompetence are expected (see Chapter 8).

• Detrimental long-term effects on the dentition and the periodontium caused by traumatic occlusal forces, the spacing of the teeth in the alveolar housing, or previous camouflage orthodontic treatment may be seen (see Chapter 5 and 6).

• Temporomandibular disorder (TMD) should be looked for but is not generally problematic in these individuals (see Chapter 9).

Clinical Characteristics

• Separation of the lips at rest of >4 mm

• Excessive dental show with the upper lip at rest and excessive gingival show with a broad smile

• Flaccid lips with more effort required to bring them into closure (i.e., mentalis strain and lip incompetence)

• Excessive prominence of the lips with everted vermillion borders when viewed in profile

• Typically a mouth-breathing habit and an open-mouth posture with a protrusive tongue

Dental Findings

• Maxillary and mandibular incisor proclination

• Exaggerated curve of Spee in the maxilla and a reverse curve in the mandible

• Frequently with narrow maxillary arch width

• Frequently with a Class II molar relationship, although a Class I or Class III malocclusion may be present

• Frequently with interdental spacing in the anterior dentition of the maxilla and mandible

• Despite incisor proclination, presence of adequate periodontal support without gingival recession, labial bone dehiscence, or fenestration is typical

Treatment Pitfalls

When considering orthognathic surgery for the individual with bimaxillary dental protrusion, there must be a compelling aesthetic or functional rationale for the shortening of the anterior vertical dimension of the face and the alteration of the horizontal projection (Figs. 24-1 through 24-11).18,41,46,64,65,80,115 When present, facial aesthetic disharmony in association with bimaxillary dental protrusion is generally characterized by the following:

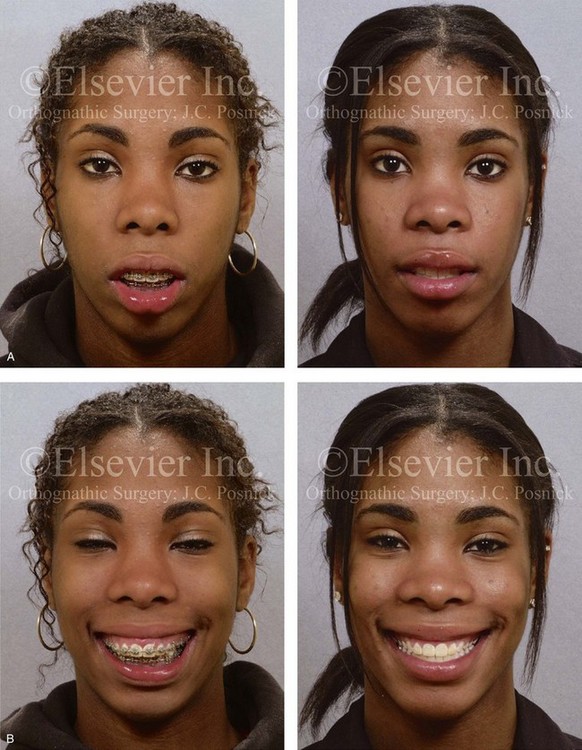

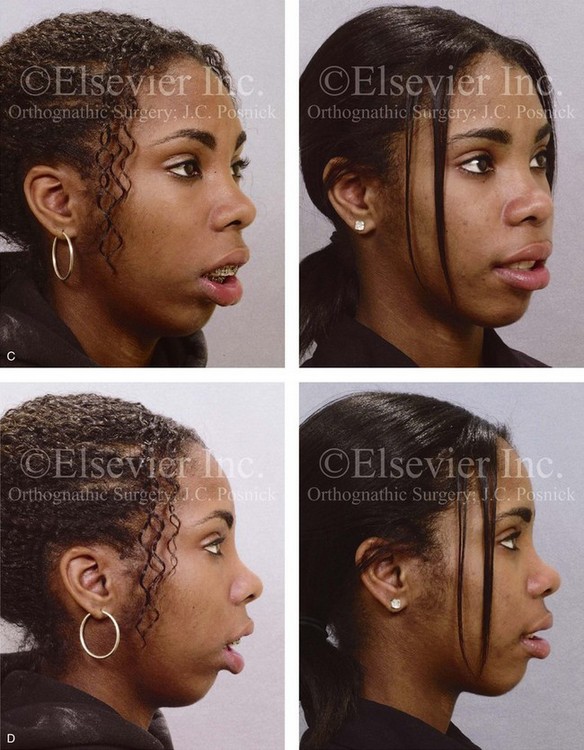

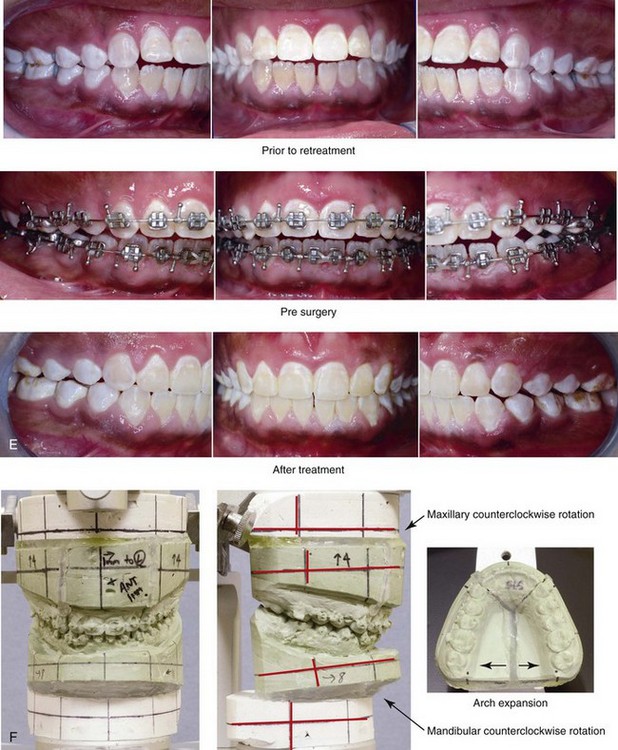

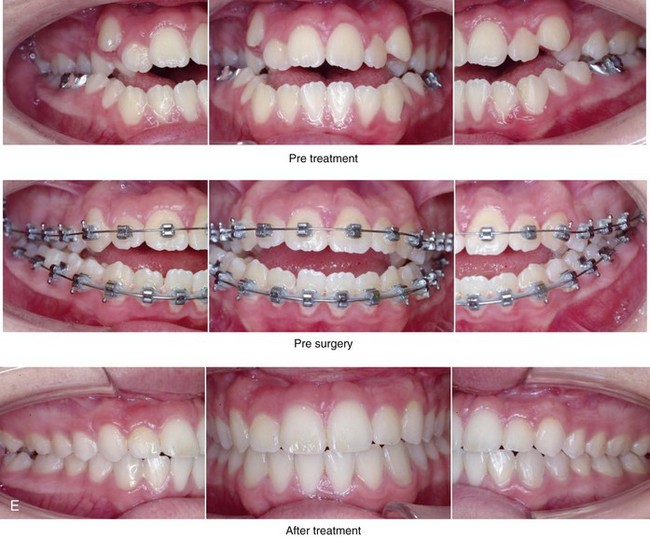

Figure 24-1 A 16-year-old girl was referred by her orthodontist for the evaluation of lip incompetence, anterior open bite, gummy smile, weak chin, and nasal obstruction. Orthodontics had previously been carried out without extraction therapy. The patient presented with a Class II anterior open bite dental protrusive malocclusion. A combined orthodontic and surgical approach was recommended. With non-extraction orthodontic decompensation complete, the patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (arch expansion, correction of the curve of Spee, vertical intrusion, minimal horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (vertical reduction and horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before retreatment, with orthodontics in progress, and after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning.

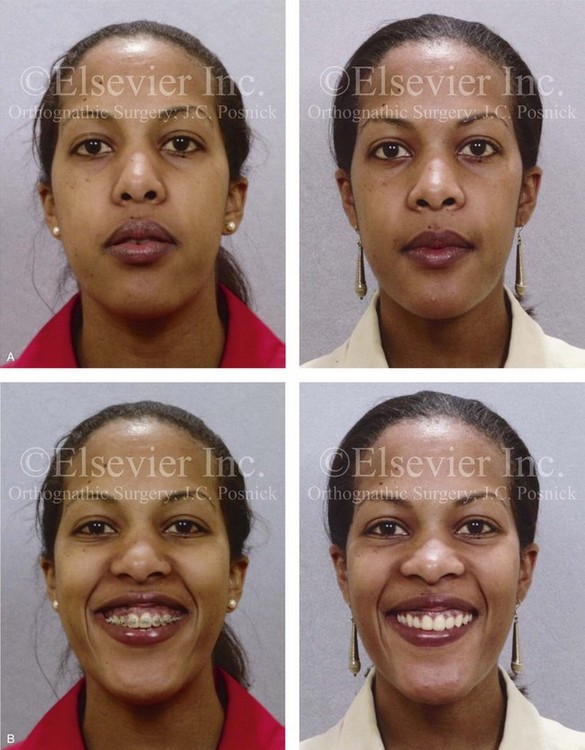

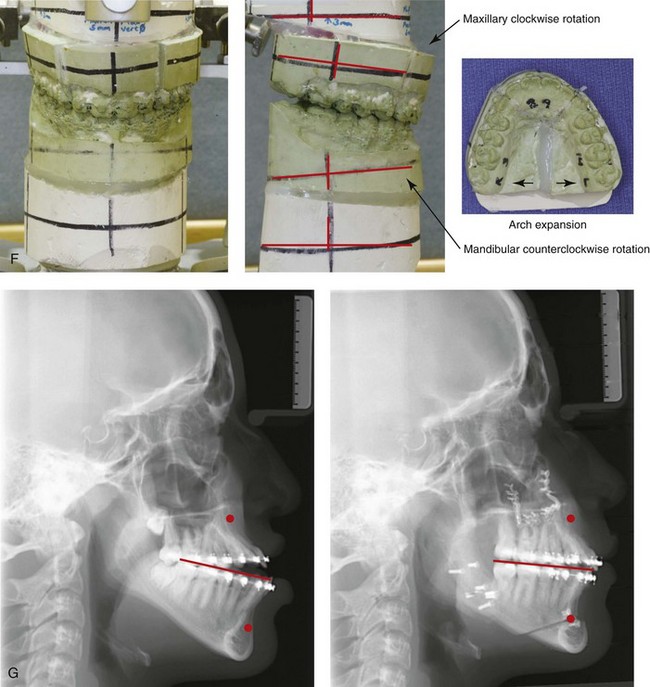

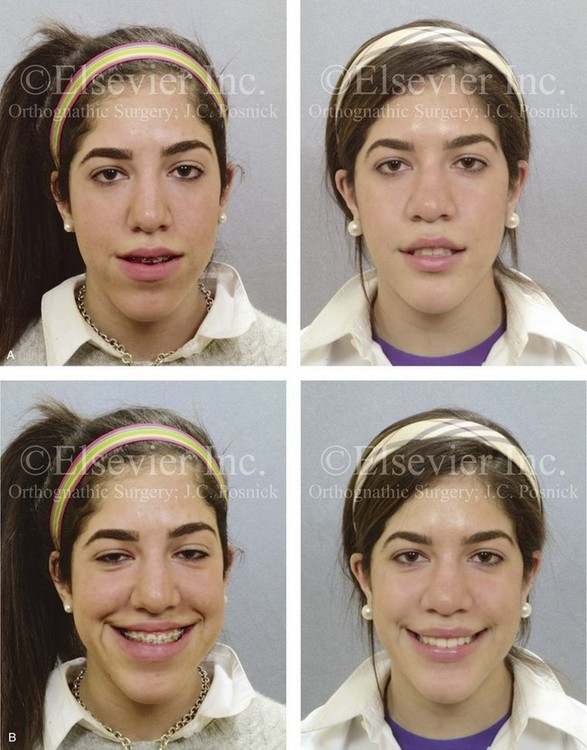

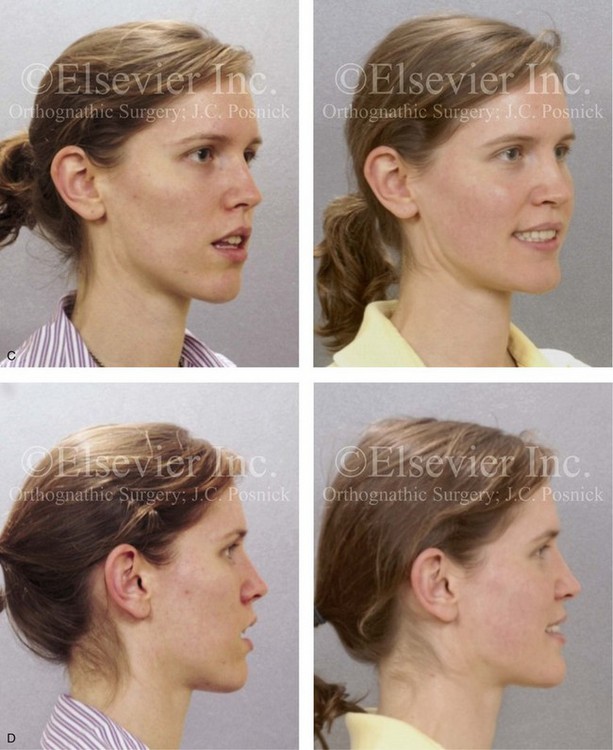

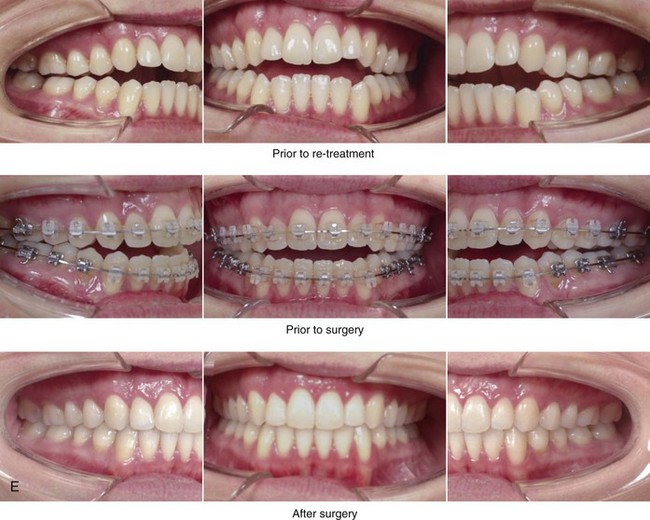

Figure 24-2 A 28-year-old woman arrived for the evaluation of malocclusion, gummy smile, lip incompetence, and nasal obstruction. She presented with a Class III anterior open-bite dental protrusive malocclusion. She underwent a combined orthodontic and surgical approach without extractions. The patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (transverse expansion, vertical intrusion, minimal advancement, and clockwise rotation); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (minimal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (vertical reduction and horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before treatment, with orthodontics in progress, and 3 years after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

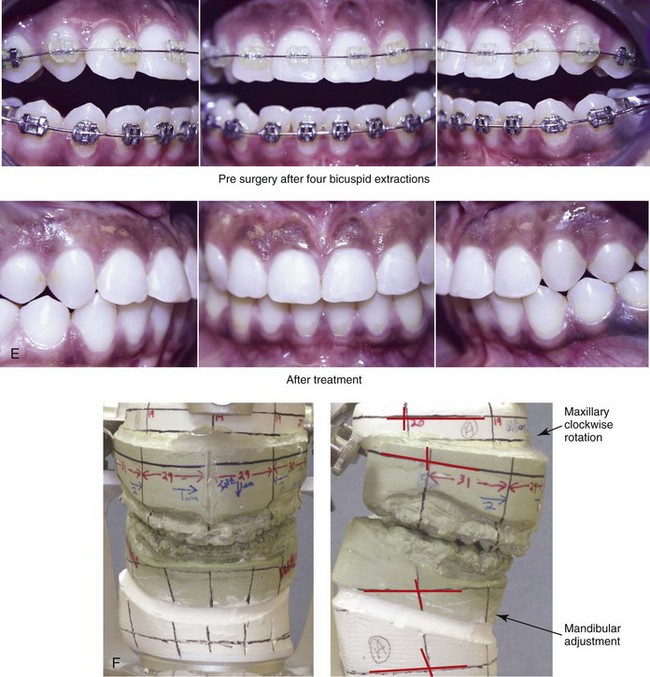

Figure 24-3 A 24-year-old woman was referred by her orthodontist for surgical evaluation. She presented with a Class III anterior open-bite dental protrusive malocclusion. She underwent four bicuspid extractions with orthodontic decompensation followed by orthognathic surgery. Her procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (clockwise rotation, horizontal advancement, arch expansion, and vertical shortening); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (minimal clockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views with orthodontics in progress and after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning.

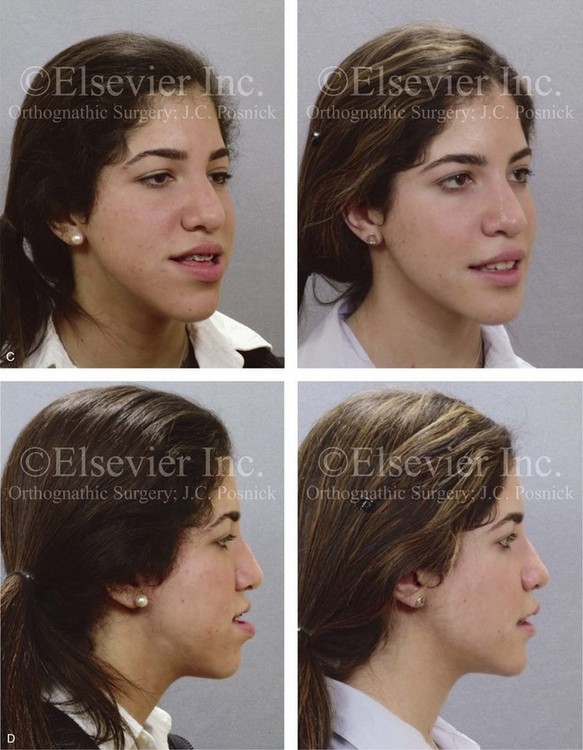

Figure 24-4 A 28-year-old Hispanic woman was referred by her orthodontist for the evaluation of malocclusion and lip incompetence. She was found to have a Class III anterior open-bite malocclusion and lifelong nasal obstruction. She underwent non-extraction orthodontic decompensation followed by surgery. Her procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (correction of the arch form); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (minimal counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before orthodontics and after treatment. Note the limited overjet as a result of mild dental relapse. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

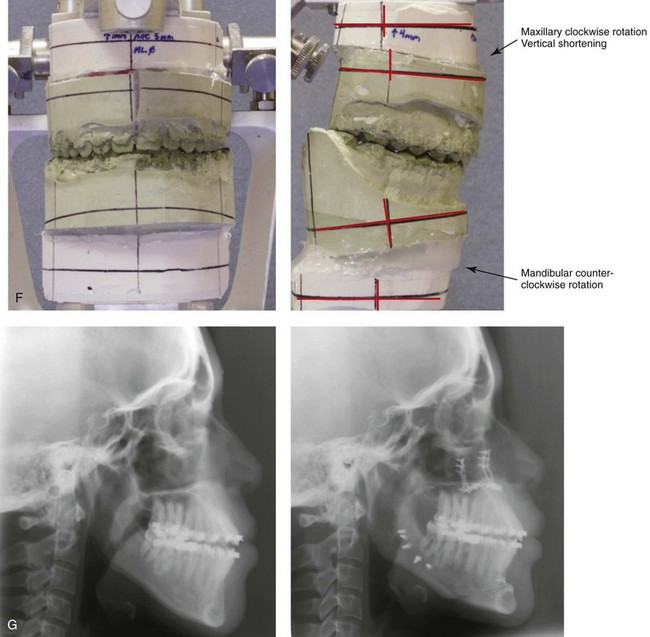

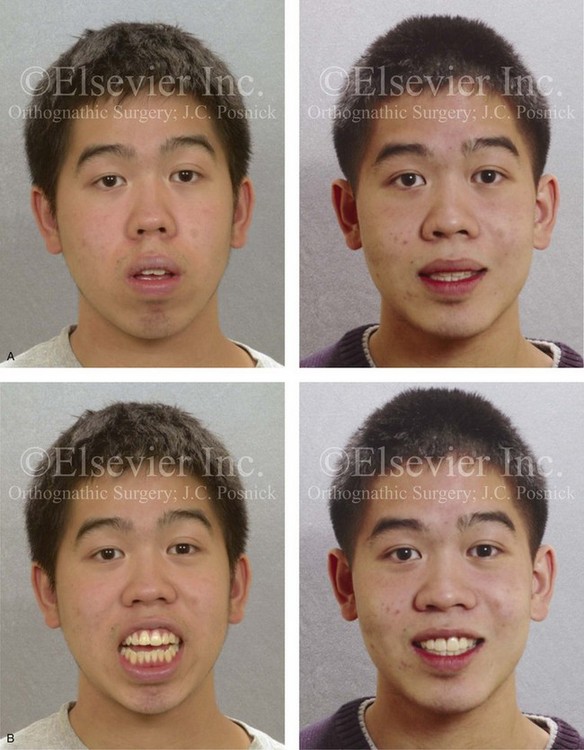

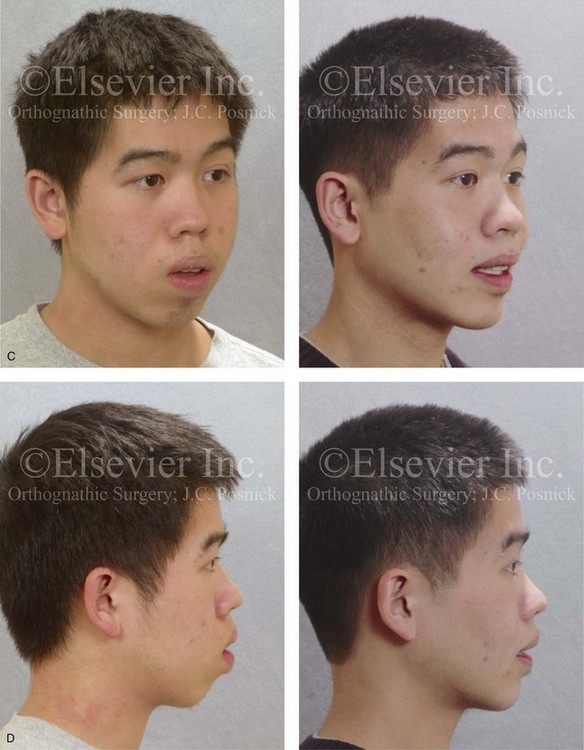

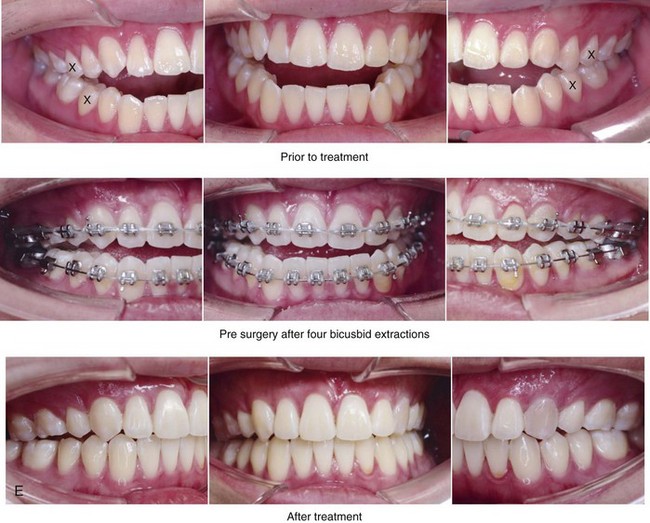

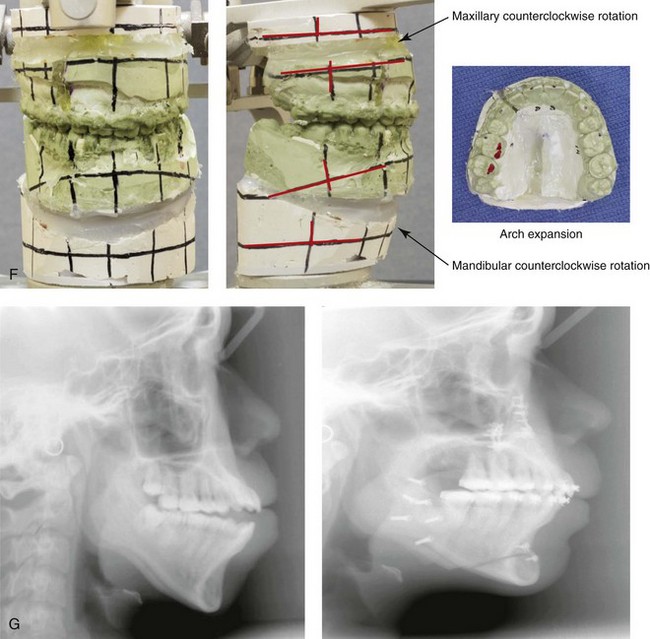

Figure 24-5 An 18-year-old Asian man was referred for surgical evaluation. He presented with a Class III anterior open-bite dental protrusive malocclusion. Concerns included nasal obstruction, gingivitis, gummy smile, anterior open-bite malocclusion, lip incompetence, and retrusive profile. Orthodontic decompensation was carried out and included four bicuspid extractions. The patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (vertical shortening, minimal horizontal advancement, counterclockwise rotation, and transverse widening); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (minimal horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (vertical shortening and horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before treatment, before surgery with four bicuspid extractions, and after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment. Despite the bicuspid extractions, procumbency remains.

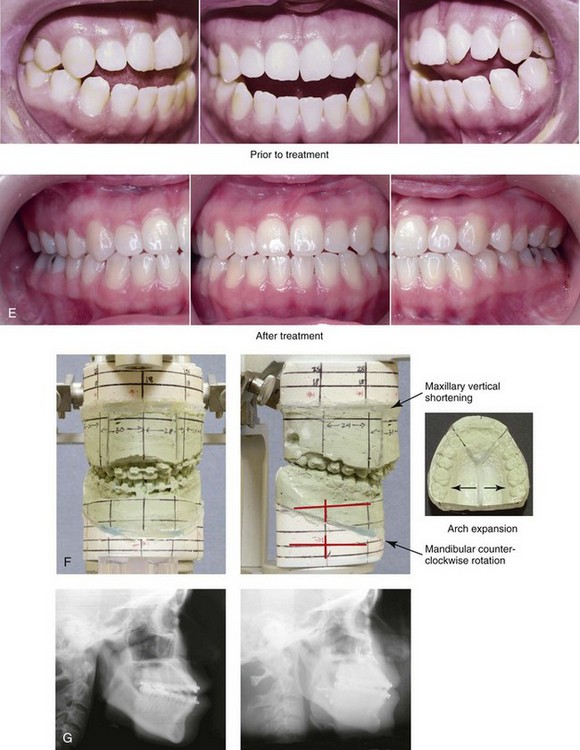

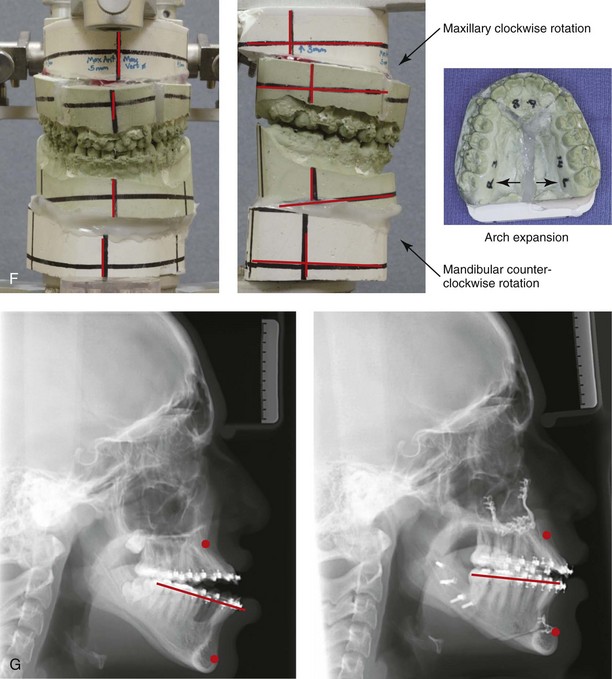

Figure 24-6 One of two 15-year-old twin girls who was referred for surgical evaluation. She presented with a Class III anterior open-bite dental protrusive malocclusion. Orthodontic treatment was carried out without extractions, and maxillary incisor procumbency remained. The patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement, vertical shortening, clockwise rotation, and arch expansion); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (minimal horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (vertical shortening and horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before orthodontics, before surgery, and after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that demonstrate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

Figure 24-7 The 15-year-old twin sister of the patient shown in Figure 24-6 was also referred for surgical evaluation. She underwent a combined orthodontic and surgical approach without extractions. She presented with a Class III anterior open-bite dental protrusive malocclusion. The patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement, vertical shortening, clockwise rotation, and arch expansion); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (vertical shortening and horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before treatment, before surgery, and after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

Figure 24-8 A 28-year-old woman arrived for the evaluation of malocclusion, lip incompetence, nasal obstruction, and anterior open bite malocclusion. She had previously undergone Phase I orthodontics that included rapid palatal expansion and an attempt at growth modification before graduating from high school. She now presented with a Class II anterior open-bite dental protrusive malocclusion. She underwent a combined orthodontic and surgical approach without extractions. The patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (vertical intrusion, horizontal advancement, correction of the curve of Spee, and arch width expansion); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (advancement and counterclockwise rotation); and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before treatment, with orthodontics in progress, and after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

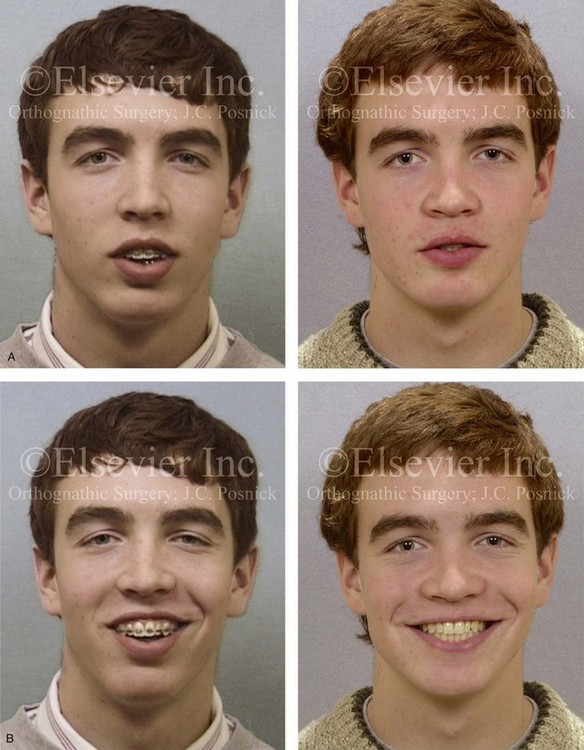

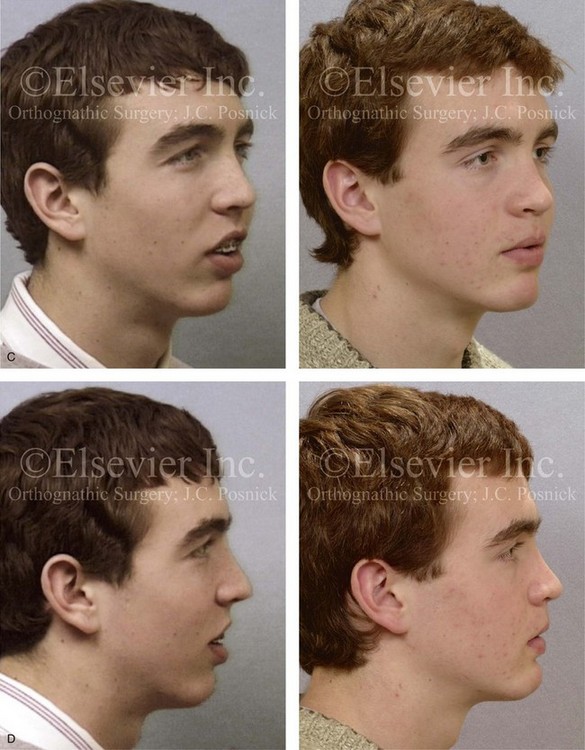

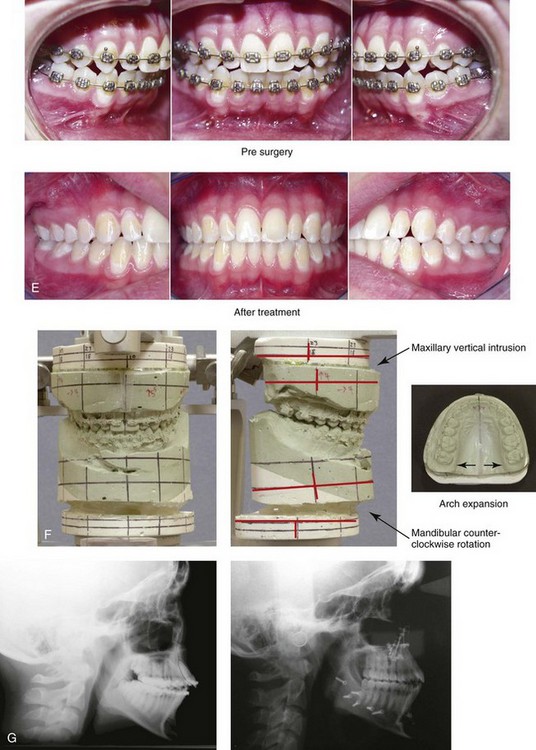

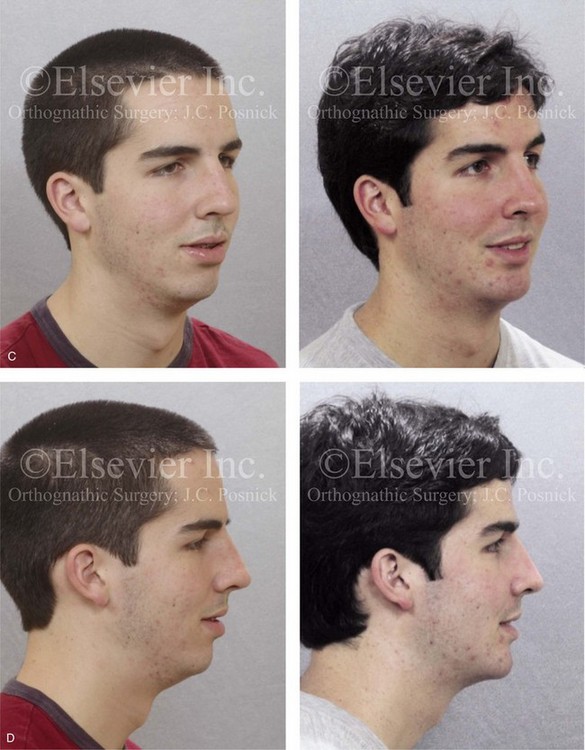

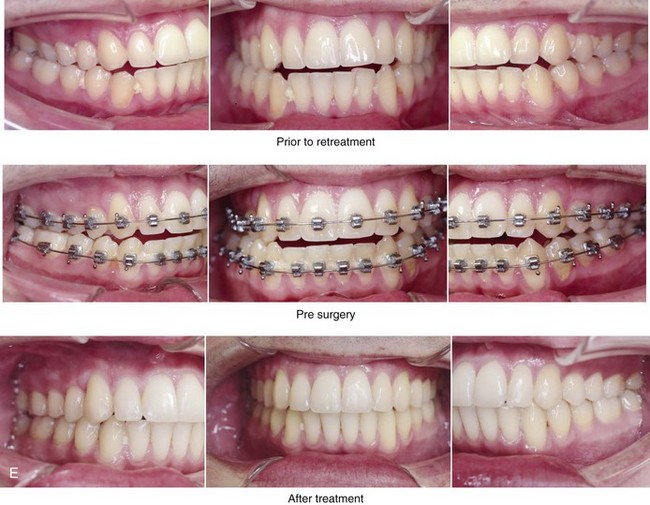

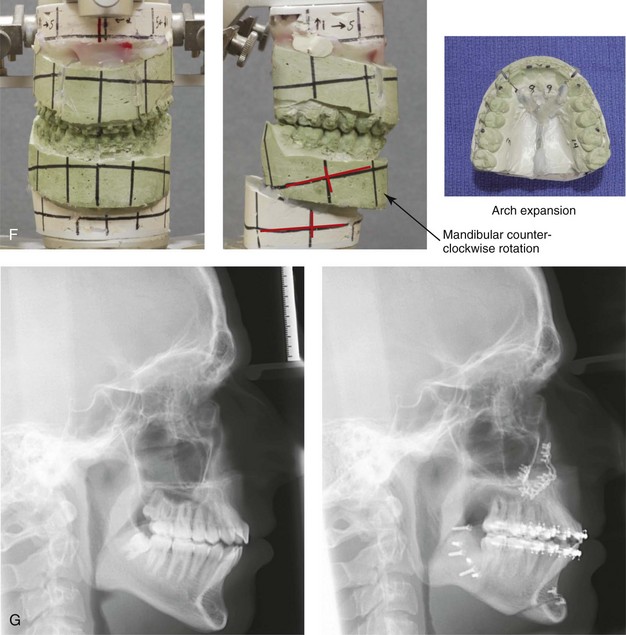

Figure 24-9 A 17-year-old Caucasian boy was referred for the surgical evaluation of gummy smile, lip incompetence, and Class II anterior open-bite protrusive malocclusion. He presented with orthodontics in progress. The patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement, vertical shortening, and arch expansion); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (vertical shortening and horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before surgery and after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

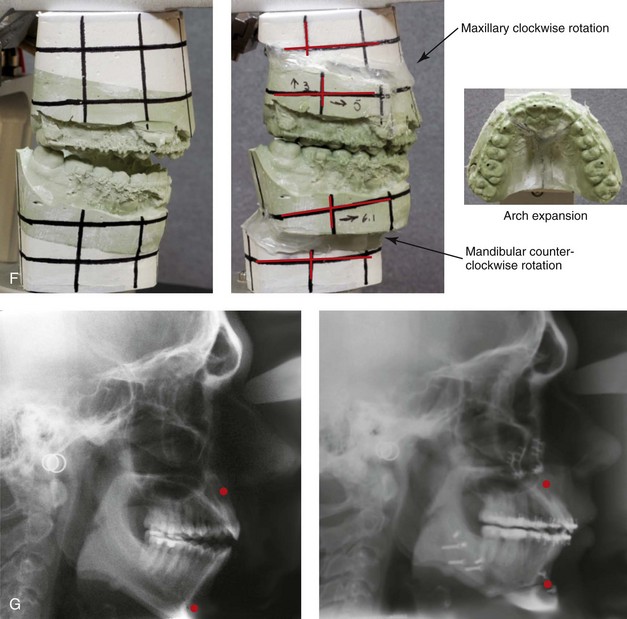

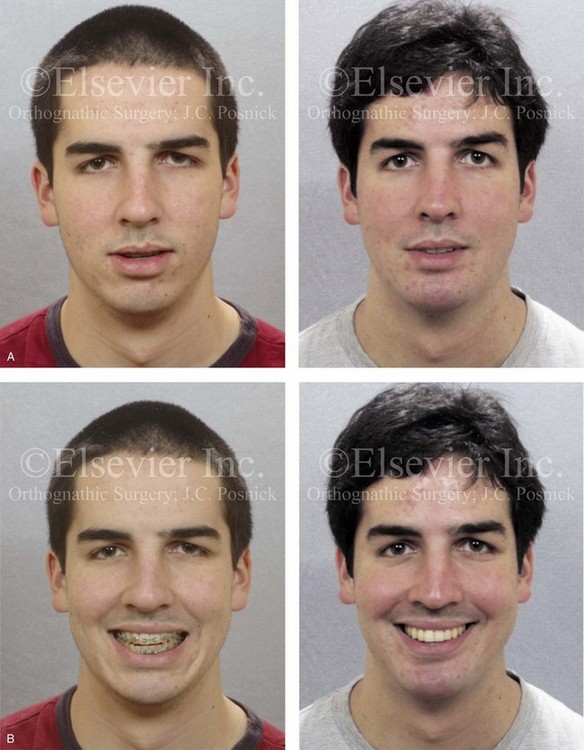

Figure 24-10 A 22-year-old Caucasian man was referred for the surgical evaluation of an anterior open-bite bimaxillary protrusive malocclusion. He has lip incompetence with mentalis strain and limited horizontal jaw projection, and his nasal airway was open without obstruction. He agreed to a combined orthodontic and surgical approach. The patient’s procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement, clockwise rotation, and arch form correction); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); and osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement). A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before orthodontics, before surgery and after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

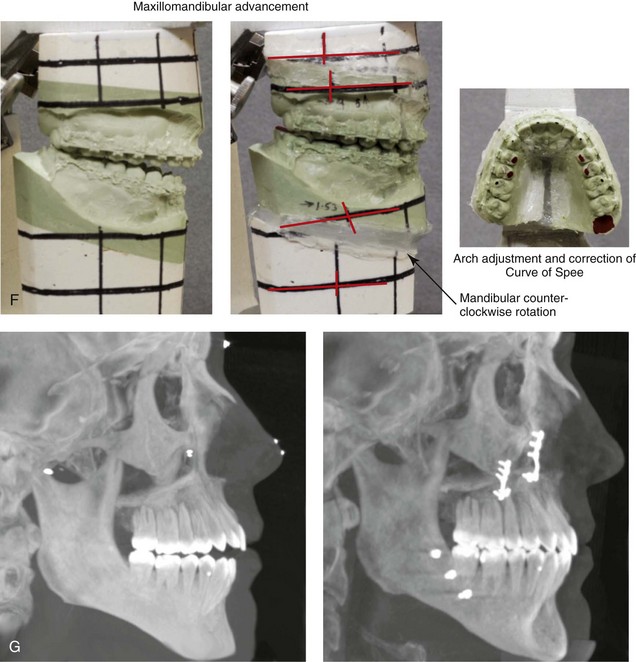

Figure 24-11 A 20-year-old Caucasian man was referred for the surgical evaluation of horizontal deficiency of both jaws and anterior open-bite malocclusion. Orthodontics had previously been tried without success. The patient had a lifelong history of nasal obstruction. He agreed to a combined orthodontic and surgical approach. The patient’s procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement and arch form correction); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (vertical shortening and horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before retreatment orthodontics, before surgery and after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

• Excessive separation of the lips at rest (i.e., lip incompetence). As a general rule, lip separation at rest should be less than 4 mm.

• Excessive incisor show with the upper lip at rest. As a general rule, more than 50% of the vertical height of the incisor should be seen to be considered excessive.

• Excessive effort required to bring the lips into closure (i.e., mentalis strain).

• Significant vertical and horizontal facial disproportion when viewed in profile.

When planning the orthognathic correction, a determination is made of how much incisor procumbency is too much.96 Anterior teeth that protrude excessively are likely to be associated with lips that are prominent, everted, and separated at rest by more than 3 mm to 4 mm (i.e., lip incompetence). This will cause the individual to strain in an attempt to bring the lips together over the protruding teeth. Retracting (i.e., uprightening) the incisors with the successful closure of the open bite by whatever means tends to decrease facial convexity when the face is viewed in profile.86,93,111,112,116 If the lips are prominent but are able to comfortably close over the teeth without excessive strain, then the lip posture (i.e., the position at rest) is largely independent of the current jaw and tooth position and more a result of lip muscle tone.16,17,91,101,106,123 For such an individual, achieving correction of incisor procumbency and the open bite will have only a limited impact on lip function and prominence.4,42,90,128

Orthodontic Approach

Historical Perspective

During the early 1900s, the uncompromising non-extraction orthodontic approach set forth by Angle was the treatment of the day (see Chapter 2).5 Angle used full-banded appliances to expand the arches as a method of bringing the teeth into ideal alignment, no matter how much additional protrusion was created in the process. Calvin Case disagreed with Angle’s treatment concepts for the bimaxillary protrusive anterior open-bite problem and stated that “one of the most dangerous features of the Angle classification is the universally applied teaching that when the dentures [teeth] are placed in normal occlusion, the facial outlines will take care of themselves.”19 For the individual with bimaxillary dental protrusion, Case proposed bicuspid extraction in all four quadrants, followed by the placement of full-banded orthodontic appliances to retract the procumbent incisors into the extraction sites. It was not until well after Case’s death that these techniques for orthodontic management were popularized by two of Angle’s own students. Charles Tweed124 in the United States and Raymond Begg10 in Australia reintroduced extraction treatment into everyday orthodontic practice. The mainstay of treatment for dentoalveolar protrusion with anterior open bite continues to involve the removal of a premolar in each quadrant followed by orthodontic retraction of the protruded anterior teeth (see Chapter 17).32,36,60,61,62,73,82

Review of the Literature

There is a definite association between bimaxillary skeletal (jaw) disharmony and dentoalveolar (dental) protrusion with open bite. The standard treatment for the dentoalveolar aspects of this condition is four bicuspid extractions and then the use of maximum anchorage to orthodontically retract the anterior dentition to achieve space closure; this will also tend to decrease the chief complaint of lip fullness. The side effects of this form of treatment may include root resorption; excess lingual tipping of the anterior teeth; remodeling with dehiscence and fenestration of the cortical plate; insufficient retraction as a result of anchorage loss; and even more pronounced incisor exposure (i.e., gummy smile). Orthodontic technical maneuvers may also include the use of mini-screws as temporary anchorage devices (TADs), torque control of the upper and lower incisors, and alveolar corticotomies followed by more rapid orthodontic retraction into the bicuspid extraction sites.7,21,22,55,56,59,69,71,78,83,87,89,92,125,127 These options also run the risk of the previously mentioned negative sequelae, but they are believed to shorten overall treatment time.

Iino and colleagues described a single case of bimaxillary dental protrusion (not associated with jaw disharmony) that was treated with corticotomy-facilitated orthodontics and titanium mini-plate anchorage devices (TADs).54 The authors performed orthodontic treatment after multiple corticotomies and the placement of TADs for skeletal anchorage in an adult patient who desired a shortened treatment period. The patient had an Angle Class I molar occlusion with flaring of the maxillary and mandible incisors. Other findings included moderate dental crowding in both arches and a limited overbite relationship (i.e., a 5.5-mm overjet and a 0.5-mm overbite). The upper and lower lips were protrusive with hypermentalis activity but without lip incompetence. The treatment rendered included the placement of TADs into the buccal alveolar bone of the maxilla for skeletal anchorage; the placement of edgewise appliances on the maxillary and mandibular teeth; maxillary first premolar and mandibular second premolar extractions; corticotomies on the lingual and buccal sides in the maxillary anterior and the mandibular anterior and posterior regions; and orthodontic leveling was initiated immediately after the corticotomies. The edgewise appliances were adjusted once every 2 weeks, and the total treatment time was 1 year. Cephalometric superimposition showed no anchorage loss in the maxilla and 2 mm of loss in the mandible. Panorex radiographs showed no reduction in crest bone height and no significant apical root resorption.

Baek and colleagues completed a study to investigate the differences in skeletal, dental, and soft-tissue results found among patients with bimaxillary dental protrusion who were undergoing either four bicuspid extractions with standard orthodontic retraction or four bicuspid extractions with anterior segmental osteotomies and repositioning.8,9

• The authors concluded that bimaxillary dental protrusion individuals with a significant associated dentofacial disharmony will not respond favorably to either of these approaches. Preoperative findings in the jaw disharmony subgroup included significant vertical and horizontal skeletal disproportion with specific pretreatment characteristics of skeletal Class II malocclusion; a poorly developed chin; and a measurably long vertical facial height. These individuals were found to require bimaxillary orthognathic surgery and were therefore excluded from the study.

• The authors concluded that individuals with isolated bimaxillary dental protrusion and anterior open bite (i.e., without associated dentofacial disharmony) who were treated with extractions and anterior segmental set-back osteotomies achieved less favorable facial aesthetics as compared with those patients who were treated with 4 bicuspid extractions and classic orthodontic mechanics.

Lee and colleagues analyzed the outcomes of the treatment of bimaxillary dental protrusion involving three different approaches.70 The sample consisted of Korean adult female patients who presented with this condition (N = 65). None had yet received any orthodontic treatment or surgical procedures. These individuals were not felt to have significant vertical or horizontal skeletal disproportion of the jaws. Strict criteria for study inclusion were as follows: 1) Angle Class I molar relationship; 2) no significant anterior vertical facial discrepancy; 3) no significant anteroposterior skeletal discrepancy; 4) crowding of less than 3 mm; 5) Rickets aesthetic line to lower lip distance of more than 2 mm; (6) anterior incisal angle of less than 125 degrees; 7) chin point deviation of less than 3 mm; and 8) no symptoms of TMD.

The study patients were then divided into three treatment groups:

Group I (n = 29) was treated with four bicuspid extractions and conventional orthodontics to achieve maximum anchorage with a transpalatal arch, head gear, or both.

Group II (n = 20) was treated with four bicuspid extractions, corticotomy-assisted orthodontics, TADs in the maxilla, and anterior segmental (set-back) osteotomy in the mandible.

Group III (n = 16) was treated with four bicuspid extractions and anterior segmental (set-back) osteotomies in the maxilla and the mandible.

1. If a patient with bimaxillary dental protrusion does not have significant vertical or horizontal skeletal dysplasia and has a Class I molar relationship with proclined upper and lower incisors, then four bicuspid extractions and conventional orthodontic treatment can produce a good result.

2. If a patient with bimaxillary dental protrusion has relatively normal upper incisor inclination and a Class I molar skeletal pattern but markedly proclined mandibular incisors and poor chin development, then treatment with bicuspid extractions, anterior segmental osteotomy in the mandible, and conventional orthodontics in the maxilla will be a good option. This approach will reduce the lower lip protrusion without unwanted change of the upper incisor inclination.

3. If a patient with bimaxillary dental protrusion has severe proclination of the upper incisors, then four bicuspid extractions and corticotomy-assisted orthodontic treatment with the use of TADs will achieve maximum retraction and uprighting in the shortest treatment period and will generally produce good results.

Orthognathic and Dentoalveolar Surgical Approaches

If orthognathic surgery (i.e., Le Fort I down-fracture with segmentation and sagittal split ramus osteotomies of the mandible in combination with an osteotomy of the chin) is undertaken to treat a significant associated dentofacial disharmony or if dentoalveolar surgery (i.e., anterior segmental osteotomies) is undertaken to manage bimaxillary dentoalveolar protrusion with anterior open bite (i.e., occlusal disharmony), then the surgical option selected should be in accordance with patient-specific facial characteristics and dental findings.11–15,26,27,29,38,39,45,49,57,63,66,74,79,81,129 In this author’s opinion, the dentoalveolar surgical approach has aesthetic advantages over the standard orthodontic approach for only a very specific subgroup of patients. A key point is that neither of these dentoalveolar approaches (i.e., segmental osteotomies versus orthodontics only) will reduce the anterior lower facial height; correct significant horizontal discrepancies; or alter chin height or projection. To accomplish these objectives, orthognathic surgery is required. Details of the individual’s presenting dysmorphology are important when choosing either of the limited dentoalveolar forms of treatment (i.e., segmental osteotomies versus orthodontics only) or when selecting an orthognathic (jaw) approach.20,23,97,105,108,130

The orthognathic surgical correction of bimaxillary dental protrusion in association with excess vertical height and horizontal disproportion of the jaws should include maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy (often with segmentation) in combination with sagittal split ramus osteotomies of the mandible (see Chapter 15). This approach provides the flexibility needed to alter the maxilla and the mandible in all three dimensions (i.e., horizontal, vertical, and transverse). The maxilla will generally require anterior vertical shortening, transverse widening, correction of the curve of Spee, minimal horizontal advancement, and a degree of clockwise rotation. The mandible will generally require horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation. An osteotomy of the chin with minimal horizontal advancement is generally useful to further improve profile aesthetics and ease of lip closure. The simultaneous management of lifelong nasal obstruction may include septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and recontouring of the nasal floor. This orthognathic and intranasal approach is carried out to achieve improved head and neck function (i.e., breathing, swallowing, chewing, speech, and lip competence) and to enhance facial aesthetics.98,99

Postsurgical Orthodontic Maintenance and Detailing

Managing the details of the in-hospital and at-home convalescence during initial healing after orthognathic surgery is essential for a successful outcome (see Chapter 11). Cephalometric and Panorex radiographs as well as facial and occlusal photographs are obtained at standard postoperative intervals to document healing. If segmental maxillary osteotomies were carried out, a prefabricated splint will have been secured to the occlusal surfaces during surgery. The orthodontist sees the patient within 24 hours of splint removal and replaces the maxillary sectional arch wires with a rigid continuous one (i.e., ≈5 weeks after surgery). The teeth are ligated together to maintain the arch form. The use of a transpalatal wire or a palatal acrylic plate may also be used to stabilize the arch form for several additional months if significant transverse expansion was carried out. Close orthodontic monitoring for skeletal and dental shifts and detailing during the first 6 months after surgery is essential.

Complications, Informed Consent, and Patient Education

The orthodontist and the surgeon are frequently asked to evaluate jaw disharmonies and malpositioned teeth and then to attempt to alter nature’s events. With an understanding of the natural progression of the uncorrected bimaxillary dental protrusion associated with dentofacial disharmony and knowledge of how specific interventions will affect head and neck function and facial aesthetics, predictable results are generally achieved. Complications and patient dissatisfaction will always occur in a small percentage of individuals. The clinician’s ability to communicate the potential risks, complications, alternative approaches, and benefits of the recommended treatment plan to the patient and the patient’s family is essential to achieve a favorable result. When the patient, his or her family, and all treating clinicians are fully informed, shared responsibility for the treatment outcome is more likely (see Chapter 16).

Malocclusion after Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery

There are inherent biologic challenges to the orthodontic movement of the teeth in the alveolar process and to the surgical repositioning of the jaws or jaw segments in the individual with bimaxillary dental protrusion and an associated dentofacial disharmony.51,102,110,114,117 This includes the technical aspects of the repositioning; the initial healing requirements; and the difficulties associated with the long-term maintenance of the mechanically relocated teeth, jaws, and jaw segments. By following sound biomechanical and facial aesthetic principles, clinicians are able to carry out orthodontic treatment and surgical procedures and to effectively maintain the results in most cases. Potential intraoperative technical difficulties associated with sagittal split ramus osteotomies of the mandible and maxillary Le Fort I osteotomies can result in immediate (early) malocclusion, but this is generally preventable (see Chapter 17). Timing the surgery to limit ongoing mandibular growth from occurring afterward is usually possible (see Chapter 17). Condylar resorption after orthognathic surgery is rarely seen in the patient with bimaxillary dental protrusion (see Chapter 36). All of these factors must be taken into account to best achieve and then maintain the desired result.

Temporomandibular Disorders: The Effects of Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery

It is estimated that an average of 32% of the population reports at least one symptom of TMD, whereas an average of 55% of the population demonstrates at least one clinical sign of the condition. TMD includes various symptoms and signs that involve the temporomandibular joint, the masticatory muscles, and the related structures. The symptoms and signs may include a spectrum of referred head and neck pain; joint noise (i.e., popping, clicking, or crepitus); reduced or altered mandibular movements as a result of muscle spasm or disc displacement with or without reduction; condylar head erosion; and pain during the direct palpation of either of the temporomandibular joints or the masticatory muscles. Occlusal factors (i.e., degrees of malocclusion) are often claimed to be associated with TMD. Interestingly, the correction of a skeletal anterior open bite through orthodontics and orthognathic surgery is likely to relieve symptoms and signs of TMD; however, this is not predictable for each individual patient (see Chapter 9).1

References

1. Aghabeigi, B, Hiranaka, D, Keith, DA, et al. Effect of orthognathic surgery on the temporomandibular joint in patients with anterior open bite. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 2001; 16:153.

2. Alexander, TL, Hitchcock, HP. Cephalometric standards for American Negro children. Am J Orthod. 1978; 74:298–304.

3. Altemus, LA. Comparative integumental relationships. Angle Orthod. 1963; 33:217–221.

4. Angelle, PL. A cephalometric study of the soft tissue changes during and after orthodontic treatment. Trans Eur Orthod Soc. 1973; 267–280.

5. Angle, EH. Malocclusion of teeth, ed 7. Philadelphia: SS White Dental Mfg Co; 1907.

6. Arvystas, MG. Treatment of anterior skeletal open-bite deformity. Am J Orthod. 1977; 72:147–164.

7. Bae, SM, Park, HS, Kyung, HM, et al. Clinical application of micro-implant anchorage. J Clin Orthod. 2002; 36:298–302.

8. Baek, SH, Kim, BH. Determinants of successful treatment of bimaxillary protrusion: Orthodontic treatment versus anterior segmental osteotomy. J Craniofac Surg. 2005; 16:234.

9. Baek, SH, Yang, WS. A soft tissue analysis on facial esthetics of Korean young adults. Korean J Orthod. 1991; 21:131–170.

10. Begg, PR. Stone age man’s dentition. Am J Orthod. 1954; 40:298–312.

11. Bell, WH. Revascularization and bone healing following anterior maxillary osteotomy. J Oral Surg. 1969; 27:249.

12. Bell, WH, Condit, CL. Surgical-orthodontic correction of adult bimaxillary protrusion. J Oral Surg. 1970; 28:578–590.

13. Bell, WH. Revascularization and bone regeneration following anterior mandibular osteotomy. J Oral Surg. 1970; 28:196.

14. Bell, WH. Correction of skeletal type of anterior open bite. J Oral Surg. 1971; 29:706.

15. Bell, WH, Dann, JJ. Correction of dentofacial deformities by surgery in the anterior part of the jaws. Am J Orthod. 1973; 64:162.

16. Bloom, L. Perioral profile changes in orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod. 1961; 47:371–379.

17. Burstone, CJ. Lip posture and its significance in treatment planning. Am J Orthod. 1967; 53:262.

18. Cangialosi, T. Skeletal morphologic features of anterior open bite. Am J Orthod. 1984; 85:28–36.

19. Case, CS. Principles of occlusion and dentofacial relations. Dent Items Int. 1905; 27:489.

20. Chamberland, S, Proffit, WL. Short-term and long-term stability of surgically assisted rapid palatal expansion revisited. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011; 139:815–822.

21. Chung, KR, Oh, MY, Ko, SJ. Corticotomy-assisted orthodontics. J Clin Orthod. 2001; 35:331–339.

22. Chung, KR, Kim, YS, Linton, JL, et al. The miniplate with tube for skeletal anchorage. J Clin Orthod. 2002; 36:407–412.

23. Connole, PW, Small, EW. Combined maxillary and mandibular osteotomies: Discussion of three cases. J Oral Surg. 1971; 29:572–578.

24. Connor, AM, Moshiri, F. Orthognathic surgery norms for American black patients. Am J Orthod. 1985; 87(2):119–134.

25. Connor, AM, Moshiri, F. Advancement genioplasty: An important part of combination surgery in black American patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1988; 93:92–99.

26. Converse, JM, Horowitz, SL. The surgical orthodontic approach to the treatment of dentofacial deformities. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1969; 55:217–243.

27. Converse, JM, Horowitz, SL. Simianism: Surgical-orthodontic correction of bimaxillary protrusion. J Maxillofac Surg. 1973; 1:8–12.

28. Cox, NH, van der Linden, FPGM. Facial harmony. Am J Orthod. 1971; 60:175–183.

29. Daniel, HT, White, RP, Proffit, WR. Anterior maxillary osteotomy in dental treatment. J Am Dent Assoc. 1971; 83:338.

30. De Smit, A, Dermaut, L. Soft tissue profile preferences. Am J Orthod. 1984; 86:67–73.

31. DeLoach N: Soft tissue facial profile of North American Blacks, a self assessment.

32. Dewan, SK, Marjadi, UK. Soft tissue changes in surgically treated cases of bimaxillary protrusion. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1983; 41:116–118.

33. Diels, RM, Kalra, V, DeLoach, N, Jr., et al. Changes in soft tissue profile of African-Americans following extraction treatment. Angle Orthod. 1995; 65:285–292.

34. Drobocky, OB, Smith, RJ. Changes in facial profile during orthodontic treatment with extraction of four first premolars. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989; 95(5):220–230.

35. Drummond, RA. A determination of cephalometric norms for the Negro race. Am J Orthod. 1968; 54:670–682.

36. Dunlevy, HA, White, RP, Proffit, WR, Turvey, TA. Professional and lay judgment of facial esthetic changes following orthognathic surgery. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1974; 2:151–158.

37. Enlow, DH, Pfister, C, Richardson, E, Kuroda, T. An analysis of black and Caucasian craniofacial patterns. Angle Orthod. 1982; 52:279–287.

38. Epker, BN, Fish, LC. Surgical-orthodontic correction of open-bite deformity. Am J Orthod. 1977; 71:278–299.

39. Epker, BN. A modified anterior maxillary osteotomy. J Maxillofac Surg. 1977; 5:35.

40. Farrow, AL, Zarrinnia, K, Azizi, K. Bimaxillary protrusion in black Americans: An esthetic evaluation and the treatment considerations. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1993; 104:240–250.

41. Fields, HW, Proffit, WR, Nixon, WL, et al. Facial pattern differences in long-faced children and adults. Am J Orthod. 1984; 85:217–223.

42. Finnoy, JP, Wisth, PJ, Boe, OE. Changes in soft tissue profile during and after orthodontic treatment. Eur J Orthod. 1987; 9:68–78.

43. Fonseca, RJ, Klein, WD. A cephalometric evaluation of American Negro women. Am J Orthod. 1978; 73:152–160.

44. Foster, EJ. Profile preferences among diversified groups. Angle Orthod. 1973; 43:34–40.

45. Freihofer, HPM. Reversing segmental osteotomies of the upper jaw. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995; 96:86.

46. Freudenthaler, JW, Celar, AG, Schneider, B. Overbite depth and anteroposterior dysplasia indicators: The relationship between occlusal and skeletal patterns using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. Eur J Orthod. 2000; 22:75–83.

47. Garner, LD, Butt, MH. Malocclusion in black American and Nyeri Kenyans, an epidemiologic study. Angle Orthod. 1985; 55:139–146.

48. Garner, LD. Soft tissue changes concurrent with orthodontic tooth movement. Am J Orthod. 1974; 66:367–377.

49. Generson, RM, Porter, JM, Zell, A, Stratigos, GT. Combined surgical and orthodontic management of anterior open bite using corticotomy. J Oral Surg. 1978; 36:216–219.

50. Guinn, KE. A soft tissue cephalometric analysis for the black patient. Master’s thesis. Howard University School of Dentistry. 1982.

51. Hagler, BL, Lupini, J, Johnston, LE, Jr. Long-term comparison of extraction and nonextraction alternatives in matched samples of African American patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998; 114:393–403.

52. Hapak, FM. Cephalometric appraisal of the open-bite case. Angle Orthod. 1964; 34:65–72.

53. Holdaway, RA. A soft-tissue cephalometric analysis and its use in orthodontic treatment planning, Part I. Am J Orthod. 1983; 84:1–28.

54. Iino, S, Sakoda, S, Miyawaki, S. An adult bimaxillary protrusion treated with corticotomy-facilitated orthodontics and titanium miniplates. Angle Orthod. 2006; 76:1074–1082.

55. Im, DH, Kim, TW, Nahm, DS, et al. Current trends in orthodontic patients in Seoul National University Dental Hospital. Korea J Orthod. 2003; 33:63–72.

56. Ito, T, Nakajima, M, Arita, S, et al. Experimental study on the tooth movement with corticotomy procedure [Japanese]. Nihon Kyosei Shika Gakkai Zasshi. 1981; 40:92–105.

57. Jacobs, JD, Bell, WH. Combined surgical and orthodontic treatment of bimaxillary protrusion. Am J Orthod. 1983; 83:321–333.

58. Jacobson, A. The craniofacial skeletal pattern of the South African Negro. Am J Orthod. 1978; 73:681–691.

59. Kawakami, M, Miyawaki, S, Noguchi, H, Kitita, T. Screw-type implants used as anchorage for lingual orthodontic mechanics: A case of bimaxillary protrusion with second premolar extraction. Angle Orthod. 2004; 74:715–719.

60. Kawamoto, HK, Jr. In search of the harmonious face: Apollo revisited, with an examination of the indications for retrograde maxillary displacement (discussion). Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997; 99:1272.

61. Keating, PJ. Bimaxillary protrusion in the Caucasian: A cephalometric study of the morphological features. Br J Orthod. 1985; 12:193–201.

62. Keating, PJ. The treatment of bimaxillary protrusion. A cephalometric consideration of changes in the inter-incisal angle and soft tissue profile. Br J Orthod. 1986; 13:209–220.

63. Kim, JR, Son, WS, Lee, SG. A retrospective analysis of 20 surgically corrected bimaxillary protrusion patients. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 2002; 17:23–27.

64. Kim, YH. Overbite depth indicator with particular reference to anterior open-bite. Am J Orthod. 1974; 65:586–611.

65. Kim, YH, Vietas, JJ. Anteroposterior dysplasia indicator: An adjunct to cephalometric differential diagnosis. Am J Orthod.. 1978; 73:619.

66. Kole, H. Surgical operation on the alveolar ridge to correct occlusal abnormalities. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1959; 12:515–529.

67. Kowalski, CJ, Nasjleti, CE, Walker, GF. Differential diagnosis of adult male black and white populations. Angle Orthod. 1974; 44:346–350.

68. Kowalski, CJ, Nasjleti, CE, Walker, GF. Dentofacial variations within and between four groups of adult American males. Angle Orthod. 1975; 45:146–151.

69. Kuroda, S, Katayama, A, Takano-Yamamoto, T. Severe anterior open-bite case treated using titanium screw anchorage. Angle Orthod. 2004; 74:558–567.

70. Lee, JK, Chung, KR, Baek, SH. Treatment outcomes of orthodontic treatment, corticotomy-assisted orthodontic treatment, and anterior segmental osteotomy for bimaxillary dentoalveolar protrusion. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007; 120:1027–1036.

71. Lee, JS, Park, HS, Kyung, HM. Micro-implant anchorage for lingual treatment of a skeletal Class II malocclusion. J Clin Orthod. 2001; 35:643–647.

72. Lew, K. Profile changes following orthodontic treatment of bimaxillary protrusion in adults with the Begg appliance. Eur J Orthod. 1989; 11:375–381.

73. Lew, KK, Loh, FC, Yeo, JF, et al. Profile changes following anterior subapical osteotomy in Chinese adults with bimaxillary protrusion. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1989; 4:189–196.

74. Lew, KK. Orthodontic considerations in the treatment of bimaxillary protrusion with anterior subapical osteotomy. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1991; 6:113–122.

75. Lin, WL. A cephalometric appraisal of Chinese adults having normal occlusion and excellent facial types. J Osaka Dent Univ. 1985; 19:1–328.

76. Martin, JC. Racial ethnocentrism and judgment of beauty. J Soc Psychol. 1964; 63:59–63.

77. Miyawaki, S, Koh, Y, Kim, R, et al. Survey of young adults women regarding men’s orofacial features. J Clin Orthod. 2000; 34:367–370.

78. Miyawaki, S, Kotama, I, Inoue, M, et al. Factors associated with the stability of titanium screws placed in the posterior region for orthodontic anchorage. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003; 124:373–378.

79. Mohnac, AM. Surgical correction of maxillomandibular deformities. J Oral Surg. 1965; 23:393.

80. Moss, M, Salentijn, L. Differences between the functional matrices in anterior open-bite and in deep-bite. Am J Orthod. 1971; 60:264–280.

81. Murphey, PJ, Walker, RV. Correction of maxillary protrusion by ostectomy and orthodontic therapy. J Oral Surg. 1963; 21:275.

82. Nadkarni, PG. Soft tissue profile changes associated with orthognathic surgery for bimaxillary protrusion. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986; 44:851–854.

83. Nagasaka, H, Sugawara, J, Kawamura, H, et al. A clinical evaluation on the efficacy of titanium miniplates as orthodontic anchorage. Orthod Waves. 1999; 58:136–147.

84. Nahoum, HI. Vertical proportions and the palatal plane in anterior open-bite. Am J Orthod. 1971; 59:273–282.

85. Nahoum, HI, Horowitz, SL, Benedicto, EA. Varieties of anterior open-bite. Am J Orthod. 1972; 61:486–492.

86. Nahoum, HI. Anterior open-bite: A cephalometric analysis and suggested treatment procedures. Am J Orthod. 1975; 67:513–521.

87. Nakanishi, H. Experimental study on artificial tooth movement with osteotomy and corticotomy. Shikwa Gakuho. 1982; 82:219–252.

88. Neger, MA. A quantitative method for the evaluation of the soft tissue facial profile. Am J Orthod. 1959; 45:738–751.

89. Nishida, M, Iizuka, T, Itoi, S, et al. Clinical study of corticotomy by Kole’s method. J Jpn Oral Surg Soc. 1986; 3:81–84.

90. O’Reilly, MT. Integumental profile changes after surgical orthodontic correction of bimaxillary dentoalveolar protrusion in black patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989; 96:242–248.

91. Oliver, BM. The influence of lip thickness and strain on upper lip response to incisor retraction. Am J Orthod. 1982; 82(2):141–149.

92. Park, HS, Bae, SM, Kyung, HM, et al. Micro-implant anchorage for treatment of skeletal Class I bialveolar protrusion. J Clin Orthod. 2001; 35:417–422.

93. Park, S, Kudlick, EM, Abrahamian, A. Vertical dimensional changes of the lips in the North American black patient after four first-premolar extractions. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989; 96:152–160.

94. Peck, H, Peck, S. A concept of facial esthetics. Angle Orthod. 1970; 40:284–318.

95. Polk, MS, Jr., Farman, AG, Yancy, JA, et al. Soft tissue profile: A survey of African-American preference. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1995; 108:90–101.

96. Posen, AL. The influence of maximum perioral and tongue force on the incisor teeth. Angle Orthod. 1972; 42:285–309.

97. Posnick, JC, Fantuzzo, J, Orchin, J. Deliberate operative rotation of the maxillo-mandibular complex to alter the A-point to B-point relationship for enhanced facial esthetics. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006; 64:1687–1695.

98. Posnick, JC, Fantuzzo, JJ, Troost, T. Simultaneous intranasal procedures to improve chronic obstructive nasal breathing in patients undergoing maxillary (Le Fort I) osteotomy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007; 65:2273–2281.

99. Posnick, JC, Agnihotri, N. Managing chronic nasal airway obstruction at the time of orthognathic surgery: A twofer. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011; 69:695–701.

100. Prahl-Andersen, B, Boersma, H, van der Linden, FPGM, Moore, AW. Perceptions of dentofacial morphology by laypersons, general dentists, and orthodontists. J Am Dent Assoc. 1979; 98:209–212.

101. Proffit, WR, Gamble, JW, Christiansen, RL. Generalized muscular weakness with severe anterior open bite. Am J Orthod. 1968; 54:104–110.

102. Proffit, WR, Knight, JM. Tongue pressures and tooth stability after anterior maxillary osteotomy. J Oral Surg. 1977; 35:798–801.

103. Proffit, WR, Bell, WH. Bimaxillary protrusion. In: Bell WH, Proffit WR, White RP, eds. Surgical correction of dentofacial deformities. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1981:1015–1057.

104. Proffit, WR, Fields, HW, Moray, LJ. Prevalence of malocclusion and orthodontic treatment need in the United States: estimates from the N-HANES III survey. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1998; 13:97–106.

105. Reyneke, JP, Evans, WG. Surgical manipulation of the occlusal plane. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1990; 5:99–110.

106. Ricketts, RM. Aesthetic environment and the law of lip relation. Am J Orthod. 1968; 54:272–289.

107. Rosa, RA, Arvystas, MG. An epidemiologic survey of malocclusions among American Negroes and American Hispanics. Am J Orthod. 1978; 73:258–273.

108. Rosen, HM. Segmental osteotomies of the maxilla. Clin Plast Surg. 1989; 16:785–794.

109. Rosen, H. Aesthetics in facial skeletal surgery. Perspect Plast Surg. 1993; 6:1.

110. Rosenquist, B. Anterior segmental maxillary osteotomy: A 24-month follow-up. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993; 22:210–213.

111. Rudee, DA. Proportional profile changes concurrent with orthodontic therapy. Am J Orthod. 1964; 50:421–434.

112. Russell, DM, Nelson, RT. Facial soft tissue profile change in the North American Black with four first pre-molar extractions. J Md State Dent Assoc. 1986; 29(I):24–28.

113. Sato, S, Kaneko, M, Sasaguri, K, et al. Different mechanics for orthodontic correction of Class II openbite and Class III openbite malocclusions. Bulletin of Kanagawa Dental College. 2007; 35:65–77.

114. Scheideman, GB, Kawamura, H, Finn, RA, Bell, WH. Wound healing after anterior and posterior subapical osteotomy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985; 43:408–416.

115. Spradley, FL, Jacobs, JD, Crowe, DP. Assessment of the anteroposterior soft-tissue contour of the lower facial third in the ideal young adult. Am J Orthod. 1981; 79:316–325.

116. Stoner, MM, Lindquist, JT. A cephalometric evaluation of 57 cases treated by Dr. CH Tweed. Angle Orthod. 1956; 26:68–98.

117. Subtelny, JD. The soft tissue profile, growth and treatment changes. Angle Orthod. 1961; 31:105–122.

118. Subtelny, JD, Sakuda, M. Open bite: Diagnosis and treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1964; 50:337.

119. Sushner, N. A photographic study of the soft tissue profile of the Negro population. Am J Orthod. 1977; 72:373–385.

120. Swinehart, EW. A clinical study of open-bite. Am J Orthod. 1942; 28:18–34.

121. Tan, TJ. Profile changes following orthodontic correction of bimaxillary protrusion with a preadjusted edgewise appliance. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1996; 11:239–251.

122. Thomas, RG. An evaluation of the soft tissue facial profile in the North American black woman. Am J Orthod. 1979; 76:84–97.

123. Trouten, JC, Enlow, DH, Rakine, M, et al. Morphologic factors in open-bite and deep-bite. Angle Orthod. 1983; 53:192–211.

124. Tweed, CH. Clinical orthodontics. St. Louis: Mosby; 1966.

125. Umemori, M, Sugawara, J, Mitani, H, et al. Skeletal anchorage system for open-bite correction. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999; 115:166–174.

126. Wardlaw, DW, Smith, RJ, Hertweck, DW, et al. Cephalometrics of anterior open bite: A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1992; 101:234–243.

127. Wilcko, WM, Wilcko, MT, Bouquot, JE, Ferguson, DJ. Rapid orthodontics with alveolar reshaping: Two case reports of decrowding. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2001; 21:9–19.

128. Worms, FW, Meskin, CH, Isaacson, RJ. Open bite. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1971; 59:589.

129. Wunderer, S. Die prognathieoperation mittels frontal gestieltem maxillafragment. Oest Z Stomat. 1962; 59:98.

130. Yokoo, S, Komori, T, Watatani, S, et al. Indications and procedures for segmental dentoalveolar osteotomy: A review of 13 patients. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 2002; 17:254–263.