Bilobe Flaps

Introduction

The original design of the bilobe flap is attributed to Esser,1 who described its use in 1918 for reconstruction of nasal tip defects. Zimany2 and others expanded the use of the flap to reconstruct defects on the trunk and soles. However, most authors now share the opinion that this flap is most useful for facial reconstruction, particularly of the nose.

Biomechanics

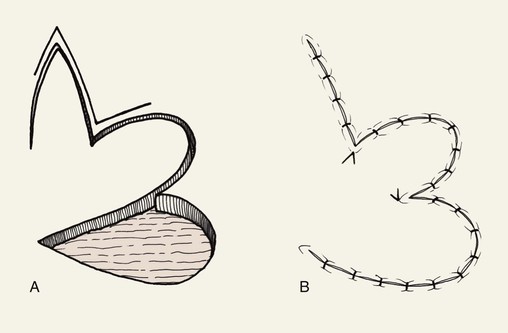

The bilobe flap would appear to be a modified rotation flap with some component of transposition. However, during transfer of the flap, there is noticeably less restriction of tissue movement than would be present with a pure rotation flap. This ease of tissue movement of the first lobe is the result, in part, of transposing the triangle-shaped peninsula of skin located between the defect and the first lobe of the flap. The transposition of this skin peninsula adjacent to the distal portion of the first lobe of the flap in essence represents a modified Z-plasty (Fig. 10-1). Likewise, there is a triangular peninsula of skin that forms between the first and second lobes that is also transposed during closure of the donor site of the second lobe. Thus, the bilobe flap in some ways represents a modified double Z-plasty. This results in repositioning of the skin adjacent to the defect and the two lobes of the flap. This in turn results in an overall reduction in wound closure tension compared with use of a single transposition or rotation flap.

Flap Design

McGregor and Soutar3 altered the design of bilobe flaps and noted that the degree of pivotal movement could be varied greatly from the original 90° between each lobe. In 1989, Zitelli4 published his experience using the bilobe flap for nasal reconstruction. He emphasized the use of narrow angles of transfer, 45° between each lobe, so that the total pivotal movement of tissue occurs over no more than 90° to 100°. This eliminated the need to excise standing cutaneous deformities, and trap-door deformities were frequently avoided. Burget5 confirmed the excellent results with this design for reconstruction of the nose. Other surgeons also advocated a similar design for repair of skin defects of the cheek, chin, and lips.6,7 They used narrow angles between the lobes of the flap and achieved better results than with use of traditionally designed bilobe flaps that are transposed through an arc of 180°.

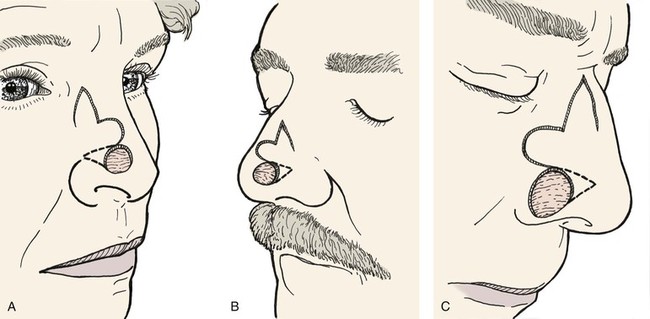

Variations of the bilobe flap are useful. On the nose, the flap may be based medially, although it works best and is most often designed with a lateral base (Fig. 10-2). The lobes of the flap may be designed with rhombic shapes for smaller defects. Bilobe flaps may be used to repair large defects located on the cheek in lieu of larger cervical-facial rotation advancement flaps. They may also be used to transfer skin from the postauricular area to cover helical rim defects that might otherwise require skin grafting.

Clinical Applications

Cheek

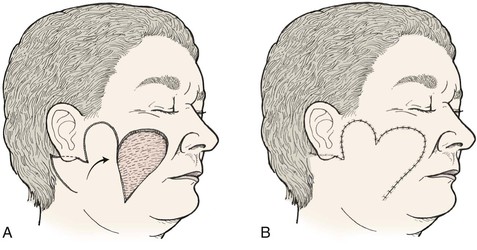

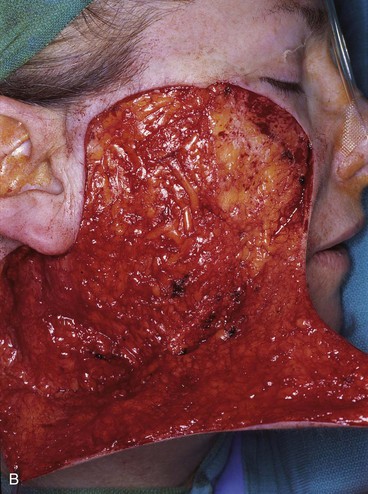

The bilobe flap may be used to repair medium-sized (3-6 cm) skin defects of the cheek. It is particularly useful when simple rotation or transposition flaps will not provide sufficient tissue for repair. This occurs when the defect is large and located in the midcheek away from the central part of the face. In this situation, the amount of remaining adjacent cheek skin available for construction of a local flap may be insufficient to cover the cheek defect and still enable closure of the flap donor site. Instead, a bilobe flap designed to recruit upper cervical skin can be useful. Obviously, the lines of wound closure do not fall in RSTLs on the cheek, but the advantage of reducing wound closure tension outweighs the disadvantages of the curvilinear scar created by use of the flap. Like all transposition flaps, bilobed flaps take advantage of lax skin adjacent to the defect to assist in wound closure. The flap is designed to resemble a mitten (Fig. 10-3). The first lobe adjacent to the cheek defect is designed slightly smaller than the defect, and the second lobe is designed to be even smaller. The flap is raised in the subcutaneous tissue plane and transposed into position. The trick is to make sure the donor defect of the second lobe can be closed primarily. This is determined by the pinch test to see if the skin in the proposed area of the second lobe is sufficiently loose to permit primary wound closure. The test is accomplished by gathering the skin of the designed second lobe between the thumb and index finger. If sufficient skin laxity is present, the pinch test should enable the surgeon to approximate the anticipated borders of the second lobe defect.

FIGURE 10-3 A, B, Bilobe flaps useful for repair of cutaneous cheek defects when simple rotation or transposition flaps will not provide sufficient tissue for repair.

Bilobed flaps may be used anywhere on the cheek; however, care should be taken in using the flap because not all the incisions required to create the flap lie parallel to the natural lines of the face, and the aesthetic result could be disappointing. The flap is best used to repair large to moderate-sized defects of the central cheek. In such cases, the remaining lateral preauricular skin is used to construct the first lobe, and the posterior auricular or superior cervical skin is the source of the second lobe.

Nose

The bilobe flap is well suited for reconstruction of the nose. Many surgeons with experience using bilobe flaps report that it is best suited for use on the caudal third of the nose. In one review of 400 nasal reconstructions, the bilobe flap was the most commonly used flap.4 With little wound closure tension on the first lobe, there is little or no distortion when the flap is used for repair of defects located near the alar rim, provided the first lobe is made sufficiently large. The use of skin adjacent to the defect allows excellent skin color and texture match. The donor site of the second lobe is closed primarily. This is possible because the second lobe is harvested from the lax skin of the upper dorsum and nasal sidewall, where primary approximation of the donor site of the second lobe can occur.

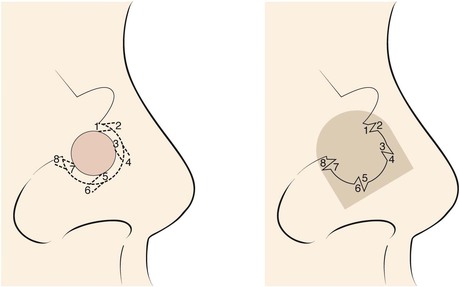

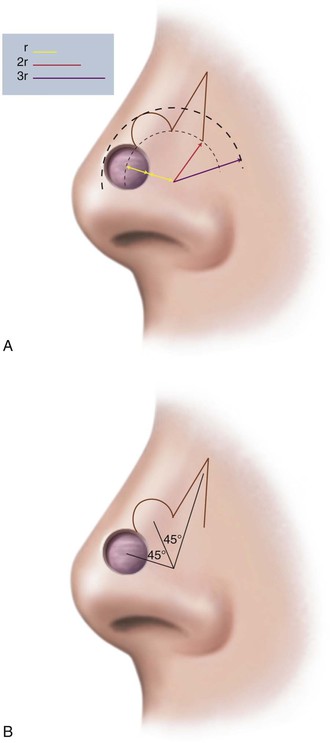

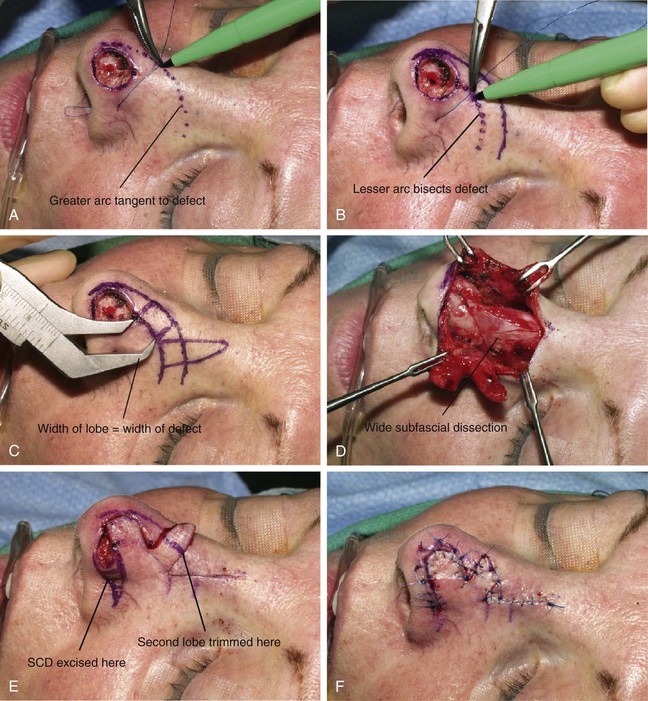

Bilobe flaps of the nose must be geometrically precise and are designed by the following method (Figs. 10-4 and 10-5).8 The radius of the defect is measured. For laterally based flaps, a point lateral to the border of the defect is marked in the alar groove that is the distance of the length of the radius. This point is used to design both lobes of the flap. Two arcs are drawn with their centers at the marked point. The first arc makes a tangent with the border of the defect most distal to the point, and the second arc passes through the center of the defect. Calipers and rulers are not used to draw the arcs because these devices measure straight-line distances. In contrast, the topography of the nose is convex in the area of the tip and dorsum. Therefore, a flexible measuring device is used. A needle with an attached suture is passed full thickness through the nose at the point marked in the alar groove. A knot is tied in the suture inside the nasal vestibule. The suture is draped from the point across the defect, and a clamp is applied to the suture at the periphery of the defect. The clamp with attached suture is then rotated about its pivotal point to indicate the first arc, which is marked with a pen. The clamp is advanced along the suture to the center point of the defect, and a second arc is drawn through the center of the defect and parallel to the first arc (Fig. 10-5B). The bases of the two lobes are designed to rest on the lesser arc. The height of the first lobe extends to the greater arc, so its height is equal to the distance between the two arcs. The width of the first lobe is equal to the width of the defect. The width of the second lobe is the same as or slightly less than that of the first lobe. The height of the second lobe is approximately 1.5 to 2.0 times greater than the height of the first lobe. The first lobe has the configuration of the defect, and the second lobe is triangular. The linear axes passing through the center of each lobe are positioned at approximately 45° from each other, with the axis of the first lobe positioned 45° from the central axis of the defect. This orientation of the lobes inevitably positions the axis of the second lobe along the center of the nasal sidewall or diagonally at the junction of the sidewall with the dorsum. The design also creates a triangular peninsula of skin between each lobe with a 45° angle. A triangle representing the eventual standing cutaneous deformity resulting from the pivot of the first lobe is marked with its apex pointing laterally and one side parallel to or in the alar groove. The base of the triangle is the lateral border of the defect, and the height of the triangle is equal to the radius of the defect.

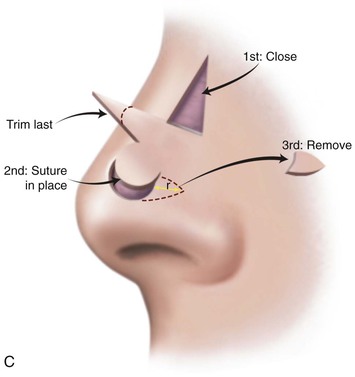

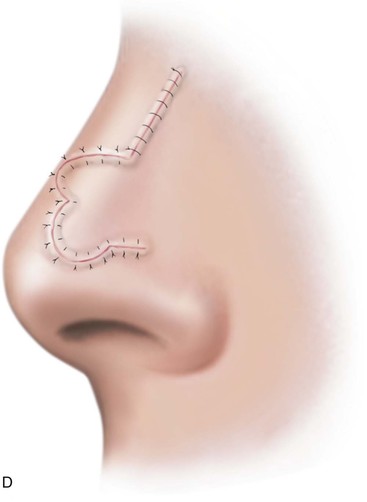

FIGURE 10-4 A, Distance equal to radius of defect (r) measured from lateral border of defect to point marked in alar groove. Two arcs drawn with centers at point. One arc passes through center and the other tangential to defect. Bases of both lobes of flap arise from lesser arc. Height of first lobe extends to second arc. Width of first lobe equals width of defect. Width of second lobe is the same as or slightly less than that of first lobe. Height of second lobe is twice height of first lobe. B, Axis of defect and two lobes of flap are approximately 45° apart. C, Donor site of second lobe closed first. First lobe transposed and standing cutaneous deformity removed. Second lobe transposed and trimmed. D, Skin incisions repaired with vertical mattress sutures. (From Baker SR: Nasal cutaneous flaps. In Baker SR, editor: Principles of nasal reconstruction, ed 2, New York, Springer, 2011.)

FIGURE 10-5 A, B, Suture rotated about point marked in alar groove is used to mark two arcs for design of bilobe flap. C, Width of defect equals width of first lobe. Base of each lobe arises from lesser arc. Height of first lobe extends to greater arc. Height of second lobe is twice height of first lobe. Width of second lobe is slightly less than width of first lobe. D, Wide undermining of flap and adjacent nasal skin is necessary. E, Standing cutaneous deformity (SCD) forms in alar groove and is excised. Second lobe is trimmed to precisely fit donor site of first lobe. F, Flap in place. G-J, Preoperative and 1-year postoperative views of patient shown in A-F. No revision surgery performed.

The flap is elevated after local anesthetic is injected. Like other nasal cutaneous flaps, it is dissected in the tissue plane between the nasal muscles and underlying perichondrium and periosteum. The flap and the remaining skin of the entire nose are completely undermined, sometimes extending the dissection into the cheek a short distance. Wide peripheral undermining of all the nasal skin is essential to reduce wound closure tension, to facilitate flap transfer, and to minimize trap-door deformity (Fig. 10-6). The donor site for the second lobe is closed first by primary approximation of the muscle layer. The first lobe is then transposed to the nasal defect and secured with a few deep dermal sutures. Next, the standing cutaneous deformity is removed in or cephalad and parallel to the alar groove. The second lobe is transposed, trimmed of its excess height so that it fits snugly without redundancy in the donor defect of the first lobe. If the thickness of the first lobe is greater than the depth of the defect, the undersurface of the lobe may be trimmed even to the level of the subdermis if necessary to match the skin thickness of the recipient site. Typically, the second lobe is thinner than the depth of the donor site for the first lobe because it is derived from the thinner skin of the cephalic nasal sidewall. This may create a mismatch in thickness that may cause a depressed contour over the nasal bridge. To prevent this, muscle and subcutaneous tissue commonly trimmed from the undersurface of the first lobe are used as free grafts. The grafts are sutured to the deep surface of the second lobe. When tissue is not removed from the first lobe, additional soft tissue augmentation of the second lobe may be accomplished with free grafts of muscle and fat harvested from the subcutaneous tissue at the junction between the nasal sidewall and the cheek.

FIGURE 10-6 A, A 1 × 1-cm skin defect of nasal tip. Bilobe flap designed for repair. Anticipated standing cutaneous deformity marked lateral to defect so scar resulting from excision will lie in alar groove. B, C, Wide undermining of flap and nasal skin essential to reduce wound closure tension. D-G, Preoperative and 3 month postoperative views. No revision surgery performed. (From: SR Baker: Nasal Cutaneous Flaps. In Baker SR, editor: Principles of Nasal Reconstruction. St. Louis, Mosby, 2002, p 118, fig 11, with permission.)

Case Reports

Case 1

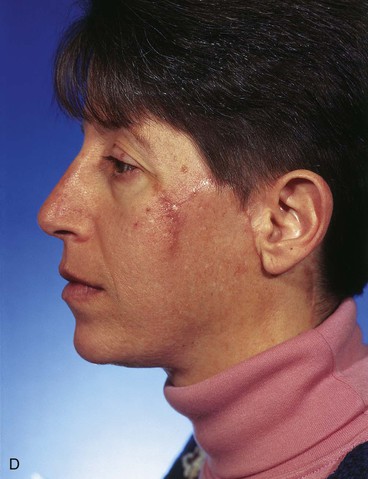

A 45-year-old woman presented with a basal cell carcinoma involving the superior cheek adjacent to the temple (Fig. 10-7). Pathologic examination of a biopsy specimen of the tumor revealed that the neoplasm displayed an aggressive growth pattern. It was removed by micrographic surgery, resulting in a 5 × 4-cm skin defect. Repair of the defect with a local skin flap was possible by designing the flap in the form of a transposition, unipedicle advancement, or bilobe flap. A bilobe flap was selected. It was designed to incorporate some rotation and advancement into the flap movement. This modification in the design of the flap was necessary because there was insufficient skin for construction of the first lobe of the flap from the remaining preauricular skin. That is, the surface area of the skin between the defect and the auricle was too small to construct a flap that would completely cover the defect. Therefore, the first lobe, by necessity, had to be in part advanced into the defect, thereby recruiting skin from the inferolateral cheek skin. The second lobe was designed to transfer skin from the superior cervical region behind and below the auricle. It was of sufficient size to repair the donor site of the first lobe.

FIGURE 10-7 A, Basal cell carcinoma of cheek skin. B, A 5 × 4-cm skin defect after micrographic surgical excision. Modified bilobe flap designed for repair of wound. C, Flap dissected in sub-SMAS tissue plane and transferred by pivotal and advancement tissue movement. D, Postoperative view at 2 months. No revision surgery performed. (From Baker SR: Reconstruction of facial defects. In Cummings CW, Fredrickson JM, Harker LA, et al, editors: Otolaryngology—head and neck surgery, ed 3, Philadelphia, Mosby, 1998.)

Case 2

The surgical options for removal of the skin graft and reconstruction of the defect with a local cutaneous flap included the transfer of adjacent facial skin into the defect in the form of a superolaterally based transposition flap, a subcutaneous tissue pedicle island advancement flap located inferior to the graft, and a bilobe flap designed lateral to the graft. The bilobe flap was selected for reconstruction. The first lobe of the bilobe flap was designed to include all of the remaining cheek skin between the skin graft and the auricle (Fig. 10-8). The first lobe was designed larger in surface area than the skin graft because split-thickness skin grafts contract on healing, giving a false indication of the actual size of the defect resulting when the graft is removed. The second lobe was designed to recruit skin from the superior cervical region behind and below the auricle. A Z-plasty was marked at the inferior portion of the planned incision line but was not required for flap transfer. The planned excision of the standing cutaneous deformity resulting from pivoting the flap was marked by horizontal lines at the inferior aspect of the graft (Fig. 10-8). The flap was incised and elevated first before excision of the skin graft. This was done to ensure that the graft could be completely excised and the exposed area covered with the flap while still achieving closure of the flap donor site. The graft was subsequently excised and the flap transferred into the defect (Fig. 10-9). The standing cutaneous deformity developing from flap transfer was excised parallel to the melolabial crease. The postoperative views (Fig. 10-10) show a more natural appearance of the patient’s cheek after removal of the skin graft.

FIGURE 10-8 A-C, Bilobe flap designed to repair cheek wound after resection of skin graft. First lobe designed larger in surface area than skin graft because split-thickness skin grafts contract on healing, giving false indication of actual size of defect resulting when graft is removed. Z-plasty marked at inferior portion of planned incision line not used for flap transfer. Anticipated standing cutaneous deformity marked with horizontal lines.

FIGURE 10-9 A, B, Same patient shown in Figure 10-8. Flap incised and dissected. C, D, One day after flap transfer.

FIGURE 10-10 A-C, Same patient shown in Figure 10-8. Postoperative views at 1 year, 5 months. Flap dermabraded 2 months after transfer.

Case 3

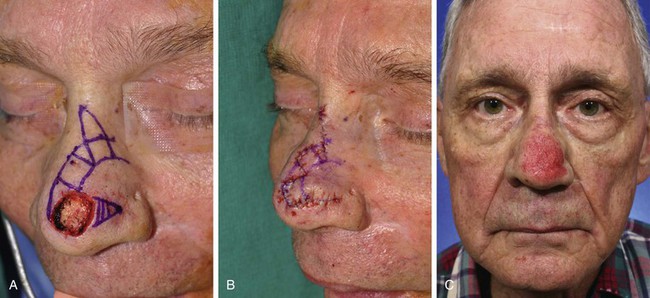

A 72-year-old man had micrographic surgery to remove a basal cell carcinoma from the nasal tip. The resulting nasal defect consisted of a superficial skin defect of the left nasal tip measuring 1.5 × 1.5-cm (Fig. 10-11). The depth and size of the wound did not justify repair with an interpolated paramedian forehead flap. Preferable surgical options for repair of the defect included a dorsal nasal flap (see discussion of this flap in Chapter 18), a full-thickness skin graft, and a bilobe nasal flap. Bilobe flaps are ideally suited for repair of skin defects 1.5 cm or less in maximum dimension on the central or lateral nasal tip and without extension to the ala. As in this case, ideally the nasal defect should be at least 0.5 cm above the margin of the nostril. All of these criteria were met in this case. In addition, the patient’s nose was relatively large, providing ample skin for construction of the flap.

FIGURE 10-11 A, A 1.5 × 1.5-cm skin defect of nasal tip. Bilobe flap designed for repair of wound. B, Flap transferred. C, Postoperative view at 2 months, immediately after dermabrasion to treat depressed scar at inferior border of first lobe of flap. D-G, Before dermabrasion and 1 month after dermabrasion.

The author usually dermabrades the entire nose, sparing the alar margins, columella, facets, and most cephalic portion of the nasal bridge and sidewalls. The procedure is performed with the patient supine and the head elevated to reduce bleeding. Nerve blocks are performed in the periphery of the nose with use of lidocaine (1% with 1 : 100,000 concentration of epinephrine), and several minutes are allowed for the block to take effect. Anesthetic is also infiltrated as superficial as possible and in the immediate subdermal plane of the skin marked for dermabrasion. Intradermal infiltration blocks the numerous sensory nerves that terminate in the dermis of the skin. In most cases, dermabrasion is performed with a 5 × 5-cm coarse grade drywall sandpaper wrapped around the surgeon’s finger. This offers the advantage of minimal equipment; there is no need for cleaning or resterilization of fraises, and the potential for aerosol spread of blood-borne pathogens is avoided. Dermabrasion is carried to the level of the upper or mid reticular dermis along the borders of the scars. Elsewhere, the depth of dermabrasion is extended to the level of punctate bleeding corresponding to midpapillary dermis. Digital palpation of the flap surface and scars is performed, and palpable irregularities are further abraded. Hemostasis is achieved by placing gauze soaked in hydrogen peroxide on the raw surface of the wound for approximately 5 minutes. The wound is dressed with a thick coat of petroleum-based ointment and covered with a nonadherent dressing. Patients are instructed to keep a generous amount of ointment on the wound until epithelialization of the wound is complete.

Case 4

Similar to the previous case, the patient shown in Figure 10-12 presented with a defect of the nasal tip skin. The defect resulted from micrographic excision of a basal cell carcinoma and measured 1.5 × 1.5-cm. The location of the defect was ideal for repair with a bilobe nasal flap for reasons discussed in Case 3. However, the nasal skin of this patient was thicker, with greater sebaceous gland hyperplasia. Figure 10-13A,C shows the 6-month postoperative results after reconstruction with a bilobe nasal flap. There is marked trap-door deformity and a depressed scar surrounding the first lobe of the flap. Patients with thick nasal skin and sebaceous gland hyperplasia have a greater risk for development of flap necrosis, trap-door deformity, and depressed scars. If these conditions are mild, they may be improved by injection of small volumes (0.1 to 0.5 mL) of triamcinolone acetonide (10 mg/mL) beneath the flap in the subfascial tissue plane. Marked trap-door deformity usually requires revision surgery.

FIGURE 10-12 A, B, A 1.5 × 1.5-cm skin defect of nasal tip in patient with thick nasal skin and sebaceous gland hyperplasia. Wound repaired with bilobe nasal flap.

FIGURE 10-13 Same patient shown in Figure 10-12 at 6 months and 16 months after reconstruction. A, C, The 6-month views show depressed scar and trap-door deformity. Revision surgery necessary and included Z-plasties of depressed scar and contouring of flap. Subsequent dermabrasion of flap also performed. B, D, Views 10 months after revision surgery show improvement in appearance of nose.

Trap-door deformity is often the result of a small hematoma occurring beneath the flap. It also may occur with inadequate undermining of the skin surrounding the periphery of the defect and in flaps that have a curvilinear configuration, such as the bilobe flap. This type of deformity is not corrected with a resurfacing procedure such as dermabrasion. Correction of the deformity frequently requires wide undermining of the skin of the flap and the adjacent area and removal of underlying scar tissue. When the scar between the flap and nasal skin is depressed, as in this case, it may also be helpful to integrate the borders of the flap with the adjacent nasal skin by use of multiple small Z-plasties (Fig. 10-14).9 Multiple Z-plasties were performed in this case to improve the depressed scar and to obscure the transition between the skin of the flap and the adjacent nasal skin. This was accomplished by first excising the depressed scar, which was separating the inferior border of the first lobe of the flap and the adjacent nasal tip skin. The flap was then widely undermined, and some scar and subcutaneous tissue were removed to contour and thin the flap. Three Z-plasties were designed along the length of the excised scar. Each triangular flap of the Z-plasty measured approximately 5 mm in length and had a 30° to 40° angle. The flaps were transposed and secured at each apex with a single 6-0 polypropylene suture placed through the tip of the flap. The remaining wound was closed in a similar fashion with simple sutures consisting of interrupted 6-0 polypropylene. Dermabrasion of the scar and adjacent nasal skin was then performed approximately 8 weeks after scar revision. The final results of the revision surgery are shown in Figure 10-13B, D. The photographs are 10 months after the surgery to refine the flap. Refinement surgery as described can be effective in converting unsightly scars from use of a bilobe flap to scars that are barely visible to the observer.

Case 5

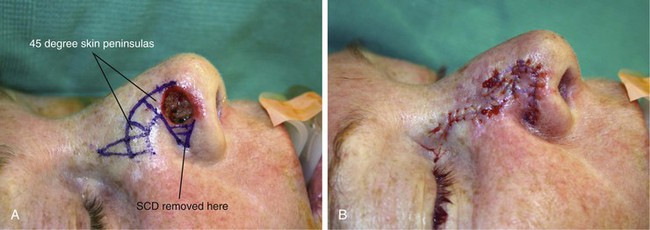

A 60-year-old woman presented with a skin and soft tissue defect of the lateral nasal tip after micrographic excision of a basal cell carcinoma. The defect measured 1 × 1-cm. The size and location of the defect were ideal for repair with a bilobe nasal flap, which was selected for wound closure. The patient’s nasal skin was thin, making the bilobe flap an even more attractive reconstructive option. Less preferable methods of reconstructing this patient included a dorsal nasal flap, a transposition flap harvested from the nasal sidewall, and a full-thickness skin graft. The bilobe flap used to repair the defect is shown in Figure 10-15. The planned excision of the standing cutaneous deformity was marked in the alar groove. As can be seen, the flap is geometrically precise. The bases of the two lobes rest on the lesser of the two arcs marked on the nose. The height of the first lobe extends from the lesser to the greater arc. The width of the first lobe equals the width of the defect. This prevents cephalic displacement of the nostril margin. The first lobe is designed with square angles at the distal border. Angulated borders tend to reduce the development of postoperative trap-door deformity compared with flaps that are designed with curvilinear borders. The second lobe has a height of 1.5 times greater than the first lobe. Its width is approximately one-third less than the first lobe. The flap was dissected in a similar fashion as previously discussed. No revision surgery was necessary.

FIGURE 10-15 A, A 1 × 1-cm cutaneous defect of lateral nasal tip. Bilobe nasal flap designed for repair. Each lobe is separated by 45° skin peninsula. Standing cutaneous deformity (SCD) marked in alar groove. B, Flap transposed. SCD removed. C-F, Preoperative and 4-month postoperative views. No revision surgery performed.

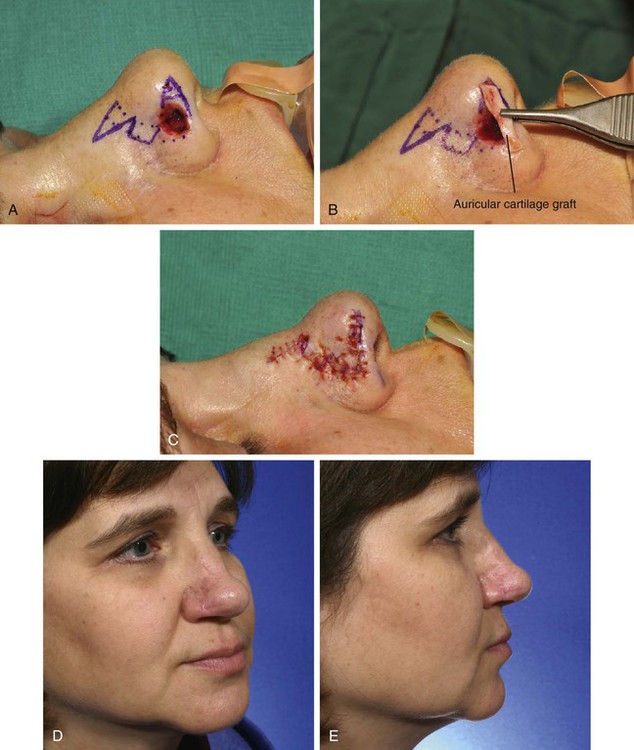

Case 6

Although bilobe flaps are usually reserved for repair of skin defects of the nasal tip, they may also be an effective method of reconstructing small defects located on the caudal dorsum and sidewall of the nose. They are particularly useful for repair of defects of the alar groove 1.5 cm or less in size. The patient shown in Figure 10-16 had a 1 × 0.8-cm skin defect of the anterior portion of the alar groove in what the author considers to be the intermediate zone between the nasal tip and ala. A medially based bilobe flap was used to reconstruct the defect. The standing cutaneous deformity was removed from the medial aspect of the defect in the lateral nasal tip. The defect encroached on the nostril margin. To prevent cephalic retraction of the nostril, an auricular cartilage graft measuring 1.5 × 0.3-cm was used to span the width of the defect and to reinforce the nostril. To accommodate the cartilage graft, a soft tissue tunnel on either side of the defect was created along the inferior border of the lateral tip and ala. The graft was inserted into the tunnels and secured to the vestibular skin with mattress sutures. The cartilage graft prevented notching and retraction as the wound healed.

FIGURE 10-16 A, A 1 × 0.8-cm cutaneous and soft tissue defect of alar groove encroaching on nostril margin. Bilobe nasal flap designed for repair. B, C, Auricular cartilage rim graft used to span caudal margin of defect. Cartilage graft and defect covered by bilobe flap. D, E, Postoperative views at 6 months. No revision surgery performed.

Figure 10-17 shows a similar size defect of the caudal nasal sidewall adjacent to the alar lobule. Similar to the previous case, this defect was repaired with a medially based bilobe flap recruiting skin from the dorsum and sidewall to construct the two lobes of the flap. Although most bilobe flaps are designed so that they are laterally based, for defects located laterally on the nasal sidewall or in the anterior portion of the alar groove, medially based bilobe flaps are preferred. This design eliminates the necessity of extending incisions into the cheek, an independent aesthetic facial region in the case of laterally located sidewall defects. In the case of defects in the anterior alar groove, it eliminates the need to remove a standing cutaneous deformity from the thick skin of the ala. In either situation, it better facilitates the use of midline nasal skin for construction of the flap.

FIGURE 10-17 A, A 1 × 1-cm skin defect of caudal nasal sidewall. B, Medially based bilobe flap designed for repair of wound. C, Flap in place. D, Postoperative view at 6 months. No revision surgery performed.

Figure 10-18 shows a nasal tip skin defect in a 75-year-old woman repaired with a medially based bilobe nasal flap. The defect measured 1.5 × 1.5-cm and resulted from micrographic excision of a basal cell carcinoma. The flap was designed with the same principles used to design laterally based flaps. However, the center point for creation of the two arcs was positioned medially at the nasal dome opposite the defect. The standing cutaneous deformity was excised at the junction of the dome and infratip. The preoperative and 2.5-year postoperative views of the nose are shown in Figure 10-19. This case demonstrates the disadvantage of medially based bilobe flaps used to repair nasal tip defects. Such flaps necessitate excision of the standing cutaneous deformity from the skin of the nasal tip, resulting in a portion of the scar that cannot be hidden in the alar groove. In contrast, laterally based flaps used to repair nasal tip defects hide the scar from excision of the standing cutaneous deformity in the alar groove. The alar groove offers a deep recess in which to camouflage scars. The patient shown in Figure 10-19 had a small nose, relatively large skin defect, and thick porous nasal skin. All of these factors contribute to the poor aesthetic result of the nasal repair. A depressed scar and a trap-door deformity account for a somewhat less than favorable outcome of the reconstruction.

FIGURE 10-18 A, A 1.5 × 1.5-cm skin defect of nasal tip. Medially based bilobe flap designed for repair of wound. Anticipated standing cutaneous deformity marked with vertical lines. B, Flap in place. Standing cutaneous deformity excised between domes and infratip segments of tip lobule.

FIGURE 10-19 A-D, Same patient shown in Figure 10-18. Preoperative and 2.5-year postoperative views. Depressed scar and mild trap-door deformity account for less than favorable aesthetic result.

References

1. Esser, JFS. Gestielte locale Nasenplastik mit Zweizipfligem lappen Deckung des sekundaren Detektes vom ersten Zipfel durch den Zweiten. Dtsch Z Chirurgie. 1918; 143:385.

2. Zimany, A. The bi-lobed flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1953; 11:424.

3. McGregor, JC, Soutar, DS. A critical assessment of the bilobed flap. Br J Plast Surg. 1981; 34:197.

4. Zitelli, JA. The bilobed flap for nasal reconstruction. Arch Dermatol. 1989; 125:957.

5. Burget, G. Creating a nasal form with flaps and grafts. In: Bardach J, ed. Local flaps and free skin grafts. Philadelphia: Mosby–Year Book, 1992.

6. Marschall, MA. Bilobed flap in head and neck reconstruction. In: Bardach J, ed. Local flaps and free skin grafts. Philadelphia: Mosby–Year Book, 1992.

7. Burget, GC, Menick, FJ. Repair of small surface defects. In: Burget GC, Menick FJ, eds. Aesthetic reconstruction of the nose. St. Louis: Mosby–Year Book, 1994.

8. Baker, SR. Nasal cutaneous flaps. In: Baker SR, ed. Principles of nasal reconstruction. St. Louis: Mosby, 2002.

9. Naficy, S, Baker, SR. Refinement techniques. In Baker SR, ed.: Principles of nasal reconstruction, 2nd ed, New York: Springer, 2011.