CHAPTER 63 Biliary Tract Motor Function and Dysfunction

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

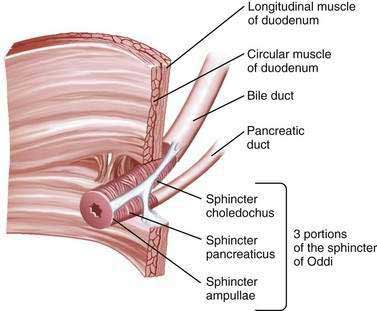

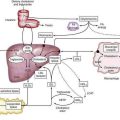

The sphincter of Oddi (SO) is composed of layers of smooth muscle that are embedded in, but functionally separate from, the muscle of the duodenal wall and that serve as a 6 to 10 mm high pressure zone. Three portions of the SO are identified: a small segment (sphincter ampullae) that covers the common channel formed by the union of the bile and pancreatic ducts (when a common channel is present); a second small portion (sphincter pancreaticus) that surrounds the beginning of the main pancreatic duct; and the largest portion (sphincter choledochus) that covers the distal bile duct (Fig. 63-1). In addition, the fasciculi longitudinales are muscle bundles that span intervals between the bile and pancreatic ducts and promote the flow of bile into the duodenum during contraction (see Chapter 62). In humans, the SO functions primarily as a resistor, with tonic contraction that limits bile flow during the interdigestive period. It also serves as a pump, with phasic contractions that facilitate the flow of bile into the duodenum, perhaps serving a housekeeping function for the distal bile duct. The SO participates in the migrating motor complex, with motilin-induced increases in the frequency and amplitude of sphincter contractions shortly before and during bursts of intense duodenal contractions. The complex neurohormonal control of biliary motility involves sympathetic, parasympathetic, and enteric nerves. Almost every neurotransmitter in the enteric nervous system has been identified in the biliary tree.

GALLBLADDER DYSKINESIA

Biliary dysmotility, or clinical problems related to abnormal biliary tract motility, can occur in either the gallbladder or the SO. Although gallbladder stasis clearly predisposes to sludge and stone formation, whether gallbladder dysfunction, or delayed emptying of the gallbladder in the absence of stones or sludge, causes biliary symptoms is unclear. Patients who experience typical biliary pain but have no evidence of gallstones may be studied with scintigraphic imaging of the gallbladder during intravenous infusion of cholecystokinin (CCK). Delayed gallbladder emptying has been reported to be predictive of pain relief after cholecystectomy,1,2 although this finding remains controversial.3,4 Delayed gallbladder emptying is more common in patients with functional bowel disorders than in control subjects.5 In many of these patients, symptoms are probably caused by the underlying functional bowel disorder, and the gallbladder dysmotility is incidental. The histologic diagnosis of chronic cholecystitis in resected gallbladders has been proposed as confirmation of a gallbladder source of symptoms,1,2 although this suggestion also has been disputed.6 A meta-analysis of 9 studies3 and a systematic review of 23 studies4 concluded that evidence that the gallbladder ejection fraction predicts symptomatic relief after cholecystectomy is lacking (see Chapter 67). A more recent, smaller meta-analysis of mostly retrospective data, however, demonstrated a statistically significant benefit to cholecystectomy in symptomatic patients with gallbladder dyskinesia.7 To complicate matters further, many patients with biliary pain, no stones on ultrasound (US), and normal CCK scintigraphy experience symptomatic improvement after cholecystectomy.8 Although many surgeons offer laparoscopic cholecystectomy to patients with biliary pain and delayed gallbladder emptying, further prospective clinical trials are necessary to determine definitively the role of CCK cholescintigraphy in the management of acalculous biliary pain.

SPHINCTER OF ODDI DYSFUNCTION

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The frequency of manometrically detected SOD in patients with an intact gallbladder has not been well studied. Elevated basal SO pressure has been reported in 40% of patients with gallbladder stones, with or without biliary pain (“biliary colic”).9 When elevated levels of liver enzymes were present, 40% of 25 patients with gallbladder stones but without bile duct stones had an elevated basal SO pressure. Ruffolo and coworkers reported that approximately 50% of 81 patients with biliary-type pain, an intact gallbladder, and no evidence of gallstones had delayed gallbladder emptying, SOD, or both.10 By contrast, no basal SO pressure elevation greater than 30 mm Hg was found in 50 asymptomatic volunteers without gallstones.11

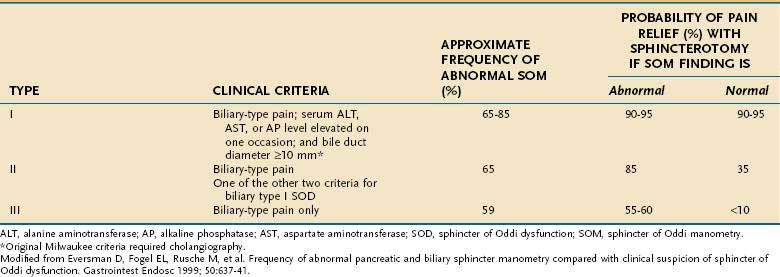

The frequency of SOD in postcholecystectomy patients with persistent or recurrent biliary-type pain has been better studied but depends on the criteria for patient selection. Pain resembling preoperative biliary pain occurs in 10% to 20% of postcholecystectomy patients.12 The most common explanation is that the preoperative symptoms were not caused by gallstones. The most likely diagnosis in this group of patients is a functional gastrointestinal disorder such as irritable bowel syndrome or functional (nonulcer) dyspepsia. SOD has been reported in 9% to 14% of patients evaluated for postcholecystectomy pain.13 When other causes of postcholecystectomy pain have been excluded and SO manometry (SOM) (see later) has been performed in a more carefully screened group, the frequency of SOD is 30% to 60%.14 When these patients are classified by the Milwaukee classification for possible SOD (Table 63-1), the frequencies of elevated basal SO pressure are 86%, 55%, and 28% for patients with suspected types I, II, and III SOD, respectively (see later).

CLINICAL FEATURES

SOD is a possible cause of three clinical conditions: (1) persistent or recurrent biliary-type pain following cholecystectomy, (2) recurrent idiopathic (unexplained) pancreatitis, and (3) biliary-type pain in patients with an intact gallbladder but without cholelithiasis (the least studied and most controversial clinical association) (Table 63-2). SOD generally occurs spontaneously, but has also been described with increased frequency in patients who have undergone liver transplantation,15 have the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome,16 are chronic opium users,17 or have hyperlipidemia.18

Table 63-2 Clinical Associations with Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction

| Strong | Biliary-type pain postcholecystectomy |

| Probable | Biliary-type pain in a patient with an intact gallbladder |

| Idiopathic acute recurrent pancreatitis | |

| Possible | Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome–associated viral and protozoal infections |

| After liver transplantation | |

| Chronic pancreatitis | |

| Hyperlipidemia | |

| Opium use |

Although biliary SOD has been diagnosed in all age groups, it is most common in middle-aged women. The female preponderance varies from 75% to 90%. The pain is typical of biliary pain; it is severe and occurs in the epigastrium or the right upper quadrant and may radiate to the back or right shoulder blade. The pain is episodic, lasts more than 30 minutes, and occurs at least once a year.19 Less than half of affected patients have abnormal liver biochemical test results with or without the pain, although transient elevation of serum aminotransferase levels during attacks of pain supports the diagnosis of SOD.

CLASSIFICATION

According to the modified Milwaukee classification system (see Table 63-1), type I SOD is diagnosed in patients with biliary-type pain, serum liver enzyme (aminotransferase or alkaline phosphatase) levels that are elevated (more than 1.1 times the upper limit of normal), and bile duct dilatation to a diameter greater than 9 mm. Type II SOD is defined as biliary-type pain and either elevated liver enzyme levels or a dilated bile duct. Type III SOD is defined as biliary-type pain without any of the other objective abnormalities. This classification system does not require that the liver enzyme elevations be timed with attacks of pain, although such an association may be a predictor of response to treatment.

The original Milwaukee classification system incorporated more stringent criteria, including aminotransferase or alkaline phosphatase elevations greater than twice the upper limit of normal on two separate occasions, biliary dilatation greater than 12 mm, and delayed drainage (>45 minutes) of bile into the duodenum at cholangiography. The stringency of these criteria has been questioned,20–22 and their use in clinical practice has diminished.

A similar classification system for possible pancreatic SOD has been proposed.23 Patients with pancreatic SOD type I have pancreatic-type pain, a serum amylase or lipase level of at least 1.1 times the upper limit of normal on one occasion, and pancreatic duct dilatation (>6 mm in the head and >5 mm in the body); those with pancreatic SOD type II have pain and one of the other criteria; and those with pancreatic SOD type III have pancreatic-type pain only. Several studies have demonstrated a high frequency (30% to 65%) of SO hypertension in patients with unexplained recurrent pancreatitis and a frequency of 50% to 87% in those with chronic pancreatitis.24 The usefulness of this classification system for pancreatic SOD has not been tested and will depend on studies of the symptomatic outcome following pancreatic sphincter ablation.

DIAGNOSIS

Noninvasive Tests

Biliary scintigraphy can be used to assess flow of bile into the duodenum and has been proposed as a safe screening test before SOM. Although scintigraphy findings are usually positive in patients with dilated bile ducts and high-grade biliary obstruction, the modality lacks sufficient sensitivity in patients with lower-grade obstruction (Milwaukee classification types II and III SOD).25 After a lipid-rich (fatty) meal or intravenous administration of CCK, the bile duct may dilate under pressure if the SO is dysfunctional, and this change can be detected on transcutaneous ultrasonography. Compared with SOM in postcholecystectomy patients, fatty meal ultrasonography has a sensitivity of 21% and a specificity of 97% for SOD.26 Similarly, after stimulation by intravenously administered secretin, the pancreatic duct may dilate, and this test therefore can be used to assess pancreatic sphincter dysfunction. Compared with SOM, secretin-stimulated ultrasonography testing has a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 82% for SOD in patients with recurrent acute pancreatitis.27

Secretin-stimulated magnetic resonance pancreatography has also been used to assess pancreatic outflow obstruction in patients with idiopathic acute recurrent pancreatitis. Preliminary reports have shown high specificity but low sensitivity rates compared with SOM.28 Similarly, in one study secretin-stimulated endoscopic ultrasonography showed limited sensitivity in the evaluation of patients with recurrent pancreatitis and manometrically proved SOD.29

Invasive Tests

Patients in whom SOD is suspected have the highest complication rates for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Such patients have a three-fold increase in the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis, with absolute rates exceeding 25%.30 Although the prophylactic placement of a temporary pancreatic stent reduces the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis,30,31 substantial morbidity and occasional mortality occur in patients who undergo ERCP for SOD. Therefore, ERCP with manometry should be reserved for persons who have severe or debilitating symptoms. Cholangiography is essential for excluding stones or tumors as the cause of biliary obstruction and associated symptoms. Although alternative biliary imaging methods, such as magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic ultrasonography, are safer than ERCP for excluding stones, tumors, and pancreas divisum, they cannot diagnose (or be used to treat) SOD.

Occasionally, an intra-ampullary neoplasm may simulate SOD. If there appears to be excess tissue in the ampulla after endoscopic sphincterotomy, biopsy specimens of the area should be obtained.32

Sphincter of Oddi Manometry

SOM is usually performed during ERCP, although it can be done in the operating room or via a percutaneous approach. All drugs that relax the SO (nitrates, calcium channel blockers, and anticholinergics) or stimulate it (narcotics and cholinergics) should be avoided for 12 hours prior to manometry. Diazepam,33 meperidine (in a maximum dose of 1 mg/kg), and fentanyl (maximum dose of 1 µg/kg)34 do not affect basal SO pressure. Studies suggest that midazolam and droperidol lower the basal SO pressure in hypertensive sphincters,35,36 although they are still used for sedation by some experts in the field. Glucagon should also be avoided, although some authorities use it if necessary to achieve cannulation and wait at least 8 to 10 minutes until sphincter function is restored before measuring pressures. In vitro and clinical data suggest that propofol does not affect the SO in a clinically relevant fashion and can be used for sedation during SOM.37 No prospective trials have evaluated the effect of inhaled general anesthetics on the SO, although these agents are used routinely in patients undergoing SOM who are difficult to sedate.

Technique

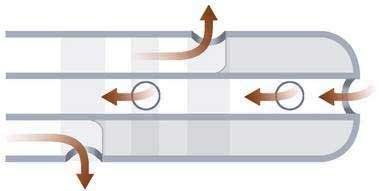

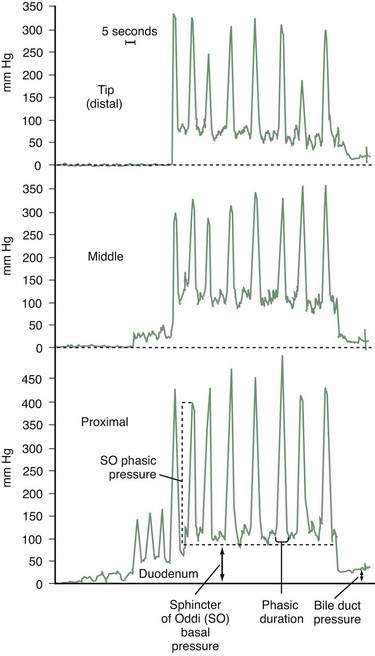

SOM uses pressure recording equipment and infusion systems similar to those used for esophageal motility studies. The infusion rate is 0.25 mL per channel using a low-compliance pump. Performance of manometry requires a two-person approach, with one person stationed at the recorder. Triple-lumen 5-French catheters are available in long-nose and short-nose types. The long-nose catheter has the advantage in the bile duct of allowing several pull-throughs without loss of cannulation, although in tortuous pancreatic ducts the nose is occasionally too long for free cannulation. The three orifices are spaced 2 mm apart and are oriented radially (Fig. 63-2). The middle port is used for aspiration, which has been shown in a controlled trial to lower the risk of pancreatitis.38 This port also allows the cannulated duct to be identified easily by the color of the aspirate: yellow from the bile duct and clear from the pancreatic duct. The middle port can accept a 0.018-inch guidewire, thereby allowing wire exchange in difficult cannulations.

When SOM is clinically indicated, many experts begin ERCP with the manometry catheter, because duodenal motility is minimized if contrast medium has not been injected. The duodenal, or zero, pressure should be measured before cannulation and after completion of manometric measurements in the SO. The catheter is withdrawn across the SO at 1- to 2-mm intervals by means of a standard station pull-through technique (Fig. 63-3). Abnormalities of the basal SO pressure should be observed on at least two pull-throughs. Depending on the clinical indication, pancreatic SOM may be performed via the same technique. Abnormal basal sphincter pressures are usually concordant for the two ducts but may occur in only the biliary or pancreatic portion of the sphincter.39 Increased basal sphincter pressure is more likely to be confined to the bile duct in persons with elevated serum liver enzyme levels and more likely to be confined to the pancreatic duct in patients with pancreatitis.40 For patients in whom the clinical indication for SOM is biliary pain and not idiopathic pancreatitis, and in whom biliary SOM produces normal findings, some authorities avoid pancreatic cannulation entirely to reduce the frequency of pancreatitis. Other experts advise studying both ducts in all patients, with the intention of performing dual sphincterotomies if either duct is hypertensive, regardless of whether the indication is biliary pain or idiopathic pancreatitis. Further studies are necessary to determine the preferable strategy. When the clinical indication for SOM is idiopathic recurrent pancreatitis and pancreatic sphincterotomy is contemplated, pancreatic manometry is mandatory. After the tracings are completed, glucagon may be administered intravenously to decrease duodenal motility, and additional meperidine or fentanyl may be given for sedation to facilitate subsequent contrast injection or endoscopic therapy. If a cholangiogram is desired, the aspirating port can be used for contrast injection. In patients with suspected SOD, placement of a temporary pancreatic stent lowers the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis, regardless of whether or not manometric measurements are abnormal.30,41

Diagnostic Use

A landmark randomized controlled study of patients with suspected type II biliary SOD conducted by Geenen and colleagues42 established that SOM predicts improvement in pain after endoscopic sphincterotomy. Patients with a basal SO pressure greater than 40 mm Hg had a clinical response rate of 91%, compared with a 25% rate in patients with a high basal pressure in whom a sham sphincterotomy was performed. For patients with a normal SO pressure, the response to sphincterotomy was only 42% and similar to that after the sham procedure (33%). These results were confirmed in a second controlled study of patients with type II SOD and an elevated sphincter pressure.43 In this study, clinical improvement was demonstrated in 11 of 13 patients treated with sphincterotomy, compared with 5 of 13 control subjects treated with sham sphincterotomy. There was no difference in pain improvement between sphincterotomy and sham sphincterotomy in patients with manometric abnormalities other than elevated basal SO pressure, namely, “tachyoddia” (increased phasic wave frequency), increased retrograde contractions, and paradoxical response to CCK.

Despite the findings of these studies, the use of SOM as a diagnostic tool remains somewhat controversial. Some uncontrolled studies suggest that more easily measurable criteria, such as elevated liver enzyme levels and biliary dilatation, are superior in predicting a response to sphincter ablation.44 Other studies suggest that manometry is highly specific for diagnosing SOD but may lack sensitivity; lack of sensitivity may account for the 42% symptom response rate to sphincterotomy in patients with biliary SOD type II and normal manometric results. A lack of sensitivity also may explain the relatively low rate of abnormal SOM results (65% to 85%) in patients with type I biliary SOD, in whom the response rate to sphincterotomy is greater than 90%.45 It is hypothesized that the relatively low frequency of sphincter hypertension in patients with type I biliary SOD is the result of a different pathogenesis of sphincter obstruction, namely, sphincter stenosis rather than sphincter hypertension.

Another possible explanation for the insensitivity of SOM is that short-term observation of sphincter pressure may not detect intermittent spasm that is not occurring at the time of the procedure. In one study, results of a second SOM were abnormal in 5 of 12 (42%) persistently symptomatic patients with an initially normal SOM result.46 An additional problem with manometry is that it is a difficult technique to perform, is not widely available, and has a success rate of only 75% to 92% in the most experienced hands.

Manometrically proved SOD appears to be less common in patients with type III biliary SOD than in those with type II SOD, and the response to sphincter ablation is only 39% to 60%.47 A response to sphincter ablation in patients with type III biliary SOD and normal SOM findings is infrequent. Obviously, pain alone is a poor indicator of any specific motility disorder. Abnormal small bowel interdigestive motor activity48 and duodenal visceral hyperalgesia in response to duodenal (but not rectal) distention49 have been demonstrated in patients with type III biliary SOD.

Placement of a pancreatic or biliary stent on a trial basis to predict a response to subsequent sphincterotomy and injection of botulinum toxin into the SO have been proposed as alternative methods of diagnosing SOD.50,51 Although preliminary data have suggested some utility to these approaches, the need for multiple procedures, with their attendant risks, and the risk of stent-induced pancreatic ductal damage have limited their widespread application.

TREATMENT

Medical Therapy

Dietary and medical therapy for suspected or documented SOD has undergone minimal study. A low-fat diet is recommended for reducing pancreaticobiliary stimulation, although no data are available to substantiate this approach. Nifedipine, nitrates, octreotide, and antispasmodics have been shown to lower basal SO pressure, although consistent clinical outcomes data are lacking. Two short-term, placebo-controlled crossover studies showed that 75% of patients with suspected or documented SOD experienced statistically less pain with use of oral nifedipine.52,53 A more recent study, however, demonstrated that slow-release nifedipine provided no clinical benefit but increased cardiovascular side effects compared with placebo.54 A single prospective study of nitrates in SOD published in abstract form revealed reduction in pain, but therapy was also limited by side effects.55 Despite these limited data, however, in light of the benign nature of SOD, medical therapy should be attempted in all patients with suspected type III SOD and in patients with less severe type II SOD before sphincter ablation is offered. A trial of antispasmodics, such as hyoscyamine, or a low-dose tricyclic antidepressant (to reduce visceral hypersensitivity) is often attempted in these patients. Patients with type II SOD and more severe pain are less likely to respond to medical therapy and can be considered for an initial trial of endoscopic therapy.

Sphincterotomy

Pain relief after sphincterotomy occurs in 35% to 42% of patients with type II biliary SOD and normal SOM results. Although this response rate is similar to that in sham-treated controls, a true clinical response likely occurs in a few patients. Sphincterotomy is clearly indicated in patients with type II SOD and abnormal SOM findings, but whether SOM is required to justify sphincterotomy in this group remains controversial. Some authorities advocate empirical biliary sphincterotomy in patients with type II SOD. This strategy has the advantage of providing therapy to those patients with normal SOM who respond to sphincterotomy, but the advantage comes at the expense of additional procedure-related complications, such as bleeding and perforation. A decision-analysis model revealed that a strategy of empirical sphincterotomy by an experienced biliary endoscopist in patients meeting criteria for type II SOD is cost-effective compared with a SOM-driven strategy.56 Further prospective studies are necessary to determine if the risks of empirical sphincterotomy in patients with type II SOD are offset by the clinical and economic benefits.

Few studies have addressed SOD in patients with biliary-type pain, an intact gallbladder, and no gallstones. Whether cholecystectomy is pathophysiologically responsible for the development of SOD or whether patients with SOD are simply more likely to have undergone cholecystectomy because of the nature of their symptoms is unclear. Cholecystectomy has been postulated to unmask preexisting subclinical SOD by removing the reservoir that serves to decompress the extrahepatic biliary system during SO spasm.57 Further, nerves that travel from the gallbladder to the SO via the cystic duct are severed during cholecystectomy, potentially leading to altered SO motility.58 Limited data, however, suggest that SOD occurs in patients with an intact gallbladder. Of patients with documented SOD and an intact gallbladder who are treated with sphincterotomy first, 43% have long-term pain relief; some additional patients eventually improve following cholecystectomy.59 Clearly, more information is needed on how to assess and treat this challenging group of patients.

SPHINCTER OF ODDI DYSFUNCTION IN PANCREATITIS

IDIOPATHIC ACUTE RECURRENT PANCREATITIS

SOD has been found in 25% to 60% of patients with idiopathic acute recurrent pancreatitis. Recurrent attacks of pancreatitis appear to be prevented by pancreatic sphincterotomy in 60% to 80% of patients with manometrically proved pancreatic sphincter hypertension, although only uncontrolled studies have been conducted.60 Endoscopic pancreatic therapy carries a higher risk of acute and long-term complications, including post-ERCP pancreatitis and papillary restenosis; the latter can sometimes lead to the development of more frequent episodes of pancreatitis or chronic pain. For the patient with an intact gallbladder and unexplained pancreatitis, some authors advocate either biliary sphincterotomy, treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid, or empirical cholecystectomy, with the implication that microlithiasis is the cause (see Chapters 58 and 65).61 Others report that biliary sphincterotomy alone benefits only one third of these patients, whereas dual (biliary and pancreatic) sphincterotomies benefit 80%, thereby suggesting that pancreatic SOD plays an important role and that pancreatic sphincter therapy must be performed along with biliary sphincterotomy.62 More studies are required to determine the preferred approach (biliary, pancreatic, or dual sphincterotomies) and to clarify the rates of success and complications associated with each approach.

CHRONIC PANCREATITIS

SOD has been described in 50% to 87% of patients with chronic pancreatitis.24 Whether SOD is the result of chronic inflammation or independently plays a role in the pathogenesis of chronic pancreatitis is not known. Endoscopic pancreatic sphincterotomy improves pain scores in 60% to 65% of patients with pancreatic SOD, although controlled studies are not available.63,64 In some cases, pancreatic sphincterotomy must be performed to facilitate other therapeutic maneuvers, such as pancreatic ductal stone extraction and stricture dilation. The role of SOM in chronic pancreatitis remains unclear.

FAILURE OF RESPONSE TO BILIARY SPHINCTEROTOMY

Possible explanations for a lack of response to biliary sphincterotomy in patients with SOD are listed in Table 63-3. Perhaps the most likely explanation is that the pain was not of pancreaticobiliary origin but was caused instead by altered gut motility or visceral hypersensitivity.49 Alternatively, the biliary sphincterotomy may have been inadequate, or restenosis may have occurred.65 The likelihood of clinical success of further biliary endoscopic treatment or of surgical sphincteroplasty in such cases is unknown.

Table 63-3 Possible Causes for Failure to Achieve Pain Relief after Biliary Sphincterotomy in Patients with Presumed Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction*

The role of residual pancreatic sphincter hypertension as a source of continuing pain in the absence of pancreatic abnormalities is unclear. Some experts advocate initial dual sphincterotomies to prevent this problem, although the reintervention rate for persistent or recurrent pain has not been different from that for historical controls in whom a single sphincterotomy (of one duct) was performed.66

Finally, some patients in whom SOD is suspected and who have shown no response to biliary sphincterotomy may have subtle chronic pancreatitis and normal pancreatographic findings. Endoscopic ultrasonography may demonstrate parenchymal changes consistent with chronic pancreatitis in these patients (see Chapter 59).67

Geenen JE, Hogan WJ, Dodds WJ, et al. The efficacy of endoscopic sphincterotomy after cholecystectomy in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:82-7. (Ref 42.)

Guelrud M, Plaz J, Mendoza B, et al. Endoscopic treatment in type II pancreatic sphincter dysfunction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;41:398. (Ref 62.)

Rolny P, Geenen JE, Hogan WJ, et al. Clinical features, manometric findings and endoscopic therapy results in group I patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:252. (Ref 45.)

Sherman S. Idiopathic acute pancreatitis: Role of ERCP in diagnosis and therapy. ASGE Clinical Update. 2004;12:1. (Ref 60.)

Sherman S, Troiano FP, Hawes RH, et al. Sphincter of Oddi manometry: Decreased risk of clinical pancreatitis with use of a modified aspirating catheter. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:462-6. (Ref 38.)

Sherman S, Troiano FP, Hawes RH, et al. Frequency of abnormal sphincter of Oddi manometry compared with the clinical suspicion of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:586-90. (Ref 14.)

Singh P, Das A, Isenberg G, et al. Does prophylactic pancreatic stent placement reduce the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis? A meta-analysis of controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:544-50. (Ref 31.)

Tarnasky PR, Hoffman B, Aabakken L, et al. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction is associated with chronic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1125-9. (Ref 24.)

Testoni PA, Caporuscio S, Bagnolo F, et al. Idiopathic recurrent pancreatitis: Long-term results after ERCP, endoscopic sphincterotomy, or ursodeoxycholic acid treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1702-7. (Ref 61.)

Toouli J, Roberts-Thomson IC, Kellow J, et al. Manometry based randomized trial of endoscopic sphincterotomy for sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gut. 2000;46:98-102. (Ref 43.)

1. Ozden N, DiBaise JK. Gallbladder ejection fraction and symptom outcome in patients with acalculous biliary-like pain. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:890-7.

2. Sabbaghian MS, Rich BS, Rothberger GD, et al. Evaluation of surgical outcomes and gallbladder characteristics in patients with biliary dyskinesia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1324-30.

3. Delgado-Aros S, Cremonini F, Bredenoord AJ, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Does gall-bladder ejection fraction on cholecystokinin cholescintigraphy predict outcome after cholecystectomy in suspected functional biliary pain? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:167-74.

4. DiBaise JK, Oleynikov D. Does gallbladder ejection fraction predict outcome after cholecystectomy for suspected chronic acalculous gallbladder dysfunction? A systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2605-11.

5. Sood GK, Baijal SS, Lahoti D, et al. Abnormal gallbladder function in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1387-90.

6. Nakano AJ, Waxman K, Rimkus D, et al. Does gallbladder ejection fraction predict pathology after elective cholecystectomy for symptomatic cholelithiasis? Am Surg. 2002;68:1052-6.

7. Ponsky TA, DeSagun R, Brody F. Surgical therapy for biliary dyskinesia: A meta-analysis and review of the literature. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2005;15:439-42.

8. Young SB, Arregui M, Singh K. HIDA scan ejection fraction does not predict sphincter of Oddi hypertension or clinical outcome in patients with suspected chronic acalculous cholecystitis. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1872-8.

9. Cicala M, Habib FI, Fiocca F, et al. Increased sphincter of Oddi basal pressure in patients affected by gall stone disease: A role for biliary stasis and colicky pain? Gut. 2001;48:414-17.

10. Ruffolo TA, Sherman S, Lehman GA, et al. Gallbladder ejection fraction and its relationship to sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:289-92.

11. Guelrud M, Mendoza S, Rossiter G, et al. Sphincter of Oddi manometry in healthy volunteers. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:38-46.

12. Luman W, Adams WH, Nixon SN, et al. Incidence of persistent symptoms after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A prospective study. Gut. 1996;39:863-6.

13. Bar-Meir S, Halpern Z, Bardan E, et al. Frequency of papillary dysfunction among cholecystectomized patients. Hepatology. 1984;4:328-30.

14. Sherman S, Troiano FP, Hawes RH, et al. Frequency of abnormal sphincter of Oddi manometry compared with the clinical suspicion of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:586-90.

15. Rerknimitr R, Sherman S, Fogel EL, et al. Biliary tract complications after orthotopic liver transplantation with cholecdochocholedochostomy anastomosis: Endoscopic findings and results of therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:224-31.

16. Cello JP, Chan MF. Long-term follow-up of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography sphincterotomy for patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome papillary stenosis. Am J Med. 1995;99:600-3.

17. Mousavi S, Toussy J, Zahmatkesh M. Opium addiction as a new risk factor of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13:528-31.

18. Szilvassy Z, Nagy I, Madacsy L, et al. Beneficial effect of lovastatin on sphincter of Oddi dyskinesia in hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:900-2.

19. Sherman S. What is the role of ERCP in the setting of abdominal pain of pancreatic or biliary origin (suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction)? Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:S258-66.

20. Lin OS, Soetikno RM, Young HS. The utility of liver function test abnormalities concomitant with biliary symptoms in predicting a favorable response to endoscopic sphincterotomy in patients with presumed sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1833-6.

21. Silverman WB, Slivka A, Rabinovitz M, et al. Hybrid classification of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction based on simplified Milwaukee criteria: Effect of marginal serum liver and pancreas test elevations. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:278-81.

22. Elta GH, Barnett JL, Ellis JH, et al. Delayed biliary drainage is common in asymptomatic post-cholecystectomy volunteers. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:435-9.

23. Petersen BT. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, part 2: Evidence-based review of the presentations, with “objective” pancreatic findings (types I and II) and of presumptive type III. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:670-87.

24. Tarnasky PR, Hoffman B, Aabakken L, et al. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction is associated with chronic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1125-9.

25. Craig AG, Peter D, Saccone GT, et al. Scintigraphy versus manometry in patients with suspected biliary sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gut. 2003;52:352-7.

26. Rosenblatt ML, Catalano MF, Alcocer E, et al. Comparison of sphincter of Oddi manometry, fatty meal sonography, and hepatobiliary scintigraphy in the diagnosis of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:697-704.

27. Di Francesco V, Brunori MP, Rigo L, et al. Comparison of ultrasound-secretin test and sphincter of Oddi manometry in patients with recurrent acute pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:336-40.

28. Testoni PA, Mariani A, Curioni S, et al. MRCP-secretin test-guided management of idiopathic recurrent pancreatitis: Long-term outcomes. Gastroinetest Endosc. 2008;67:1028-34.

29. Catalano MF, Lahoti S, Alcocer E, et al. Dynamic imaging of the pancreas using real-time endoscopic ultrasonography with secretin stimulation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:580-7.

30. Tarnasky P, Palesch Y, Cunningham JT, et al. Pancreatic stenting prevents pancreatitis after biliary sphincterotomy in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1518-24.

31. Singh P, Das A, Isenberg G, et al. Does prophylactic pancreatic stent placement reduce the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis? A meta-analysis of controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:544-50.

32. Ponchon T, Aucia N, Mitchell R, et al. Biopsies of the ampullary region in patients suspected to have sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:296-300.

33. Ponce Garcia J, Garrigues V, Sala T, et al. Diazepam does not modify the motility of the sphincter of Oddi. Endoscopy. 1988;20:87.

34. Elta GH, Barnett JL. Meperidine need not be proscribed during sphincter of Oddi manometry. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:7-9.

35. Fazel A, Burton FR. A controlled study of the effect of midazolam on abnormal sphincter of Oddi motility. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:637-40.

36. Wilcox CM, Linder J. Prospective evaluation of the effect of droperidol on sphincter of Oddi motility. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:483-7.

37. Goff JS. Effect of propofol on human sphincter of Oddi. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:2364-7.

38. Sherman S, Troiano FP, Hawes RH, et al. Sphincter of Oddi manometry: Decreased risk of clinical pancreatitis with use of a modified aspirating catheter. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:462-6.

39. Chan Y-K, Evans PR, Dowsett JF, et al. Discordance of pressure recordings from biliary and pancreatic duct segments in patients with suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:1501-6.

40. Raddawi HM, Geenen JE, Hogan WJ, et al. Pressure measurements from biliary and pancreatic segments of sphincter of Oddi: Comparison between patients with functional abdominal pain, biliary, or pancreatic disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:71-4.

41. Saad AM, Fogel EL, McHenry L, et al. Pancreatic duct stent placement prevents post-ERCP pancreatitis in patients with suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction but normal manometry results. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:255-61.

42. Geenen JE, Hogan WJ, Dodds WJ, et al. The efficacy of endoscopic sphincterotomy after cholecystectomy in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:82-7.

43. Toouli J, Roberts-Thomson IC, Kellow J, et al. Manometry based randomized trial of endoscopic sphincterotomy for sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gut. 2000;46:98-102.

44. Petersen BT. An evidence-based review of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, part I: Presentations with “objective” biliary findings (types I and II). Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:525-34.

45. Rolny P, Geenen JE, Hogan WJ, et al. Clinical features, manometric findings and endoscopic therapy results in group I patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:252.

46. Varadarajulu S, Hawes RH, Cotton PB. Determination of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction in patients with prior normal manometry. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:341-4.

47. Sherman S. What is the role of ERCP in the setting of abdominal pain of pancreatic or biliary origin (suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction)? Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:S258-66.

48. Evans PR, Bak Y-T, Dowsett JF, et al. Small bowel dysmotility in patients with postcholecystectomy sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:1507-12.

49. Chun A, Desautels S, Slivka A, et al. Visceral algesia in irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, and sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, type III. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:631-6.

50. Rolny P. Endoscopic bile duct stent placement as a predictor of outcome following endoscopic sphincterotomy in patients with suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;9:467-71.

51. Pasricha PJ, Miskovsky EP, Kalloo AN. Intrasphincteric injection of botulinum toxin for suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gut. 1994;35:1319-21.

52. Sand J, Nordback I, Koskinen M, et al. Nifedipine for suspected type II sphincter of Oddi dyskinesia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:530-5.

53. Khuroo MS, Zargar SA, Yattoo GN. Efficacy of nifedipine therapy in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: A prospective, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, cross over trial. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;33:477-85.

54. Craig AG, Toouli J. Slow release nifedipine for patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: Results of a pilot study. Intern Med J. 2002;32:119-20.

55. Cuer JC, Abergel A, Dapoigny M, et al. The efficacy of glycerol trinitrate in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. A prospective double-blind study. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:A412.

56. Arguedas MR, Linder JD, Wilcox CM. Suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction type II: empirical biliary sphincterotomy or manometry-guided therapy? Endoscopy. 2004;36:174-8.

57. Lisbona R. The scintigraphic evaluation of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. J Nuc Med. 1992;33:1223-4.

58. Luman W, Williams A, Pryde A, et al. Influence of cholecystectomy on sphincter of Oddi motility. Gut. 1997;41:371-4.

59. Choudhry U, Ruffolo T, Jamidar P, et al. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction in patients with intact gallbladder: Therapeutic response to endoscopic sphincterotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:492-5.

60. Sherman S. Idiopathic acute pancreatitis: Role of ERCP in diagnosis and therapy. ASGE Clinical Update. 2004;12:1.

61. Testoni PA, Caporuscio S, Bagnolo F, et al. Idiopathic recurrent pancreatitis: Long-term results after ERCP, endoscopic sphincterotomy, or ursodeoxycholic acid treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1702-7.

62. Guelrud M, Plaz J, Mendoza B, et al. Endoscopic treatment in type II pancreatic sphincter dysfunction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;41:398.

63. Okolo PI, Pasricha PJ, Kalloo AN. What are the long-term results of endoscopic pancreatic sphincterotomy? Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:15-19.

64. Ell C, Rabenstein T, Schneider T, et al. Safety and efficacy of pancreatic sphincterotomy in chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:244-9.

65. Manoukian AV, Schmalz MJ, Geenen JE, et al. The incidence of post-sphincterotomy stenosis in group II patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:496-8.

66. Park SH, Watkins JL, Fogel EL, et al. Long-term outcome of endoscopic dual pancreatobiliary sphincterotomy in patients with manometry-documented sphincter of Oddi dysfunction and normal pancreatogram. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:483-91.

67. Sahai AV, Mishra G, Penman ID, et al. EUS to detect evidence of pancreatic disease in patients with persistent or nonspecific dyspepsia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:153-9.