CHAPTER 23 Biliary Atresia

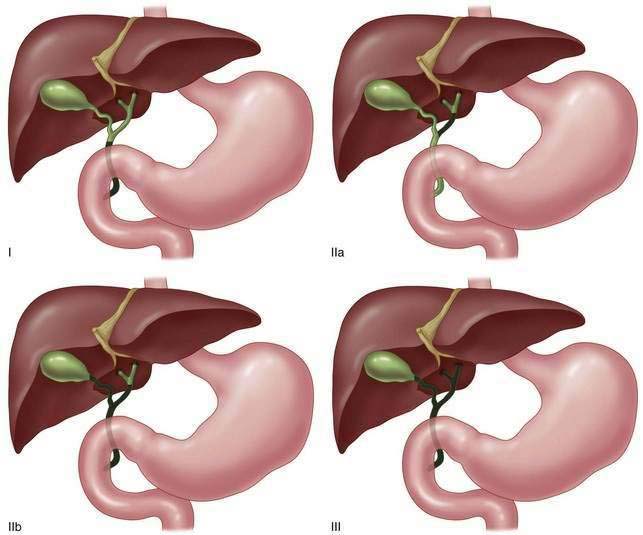

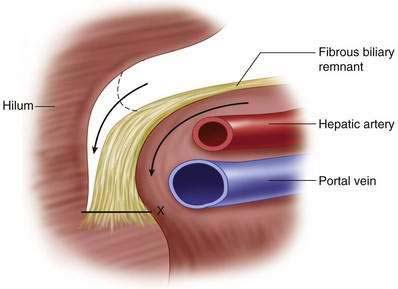

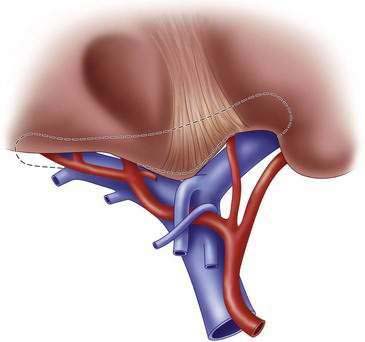

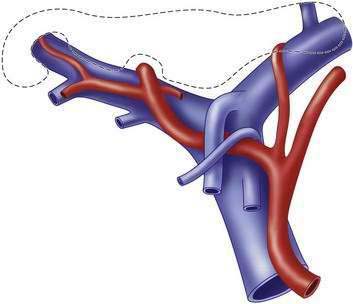

Step 1: Surgical Anatomy

Step 2: Preoperative Considerations

Step 3: Operative Steps

Anesthetic Induction

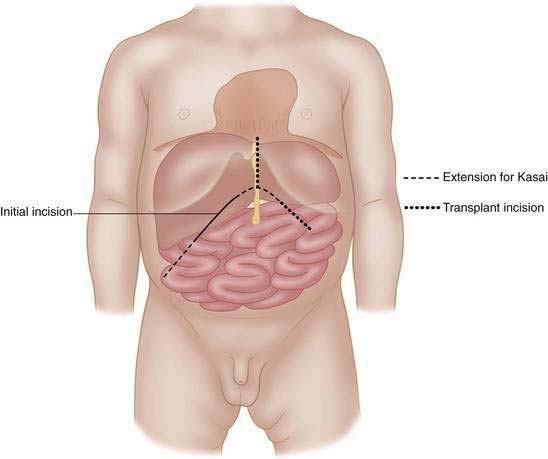

Incision

Operative Procedure Step 1: Diagnostic Confirmation

Full-strength contrast is infused under fluoroscopic guidance, taking care not to extravasate the contrast through forceful or unobserved injection.

Full-strength contrast is infused under fluoroscopic guidance, taking care not to extravasate the contrast through forceful or unobserved injection. Respiration is held by anesthesiology during the study to enhance the resolution, as residual ducts in infants with intrinsic metabolic liver disease or familial cholangiopathies are very small.

Respiration is held by anesthesiology during the study to enhance the resolution, as residual ducts in infants with intrinsic metabolic liver disease or familial cholangiopathies are very small. If no proximal contrast reaches the liver, the distal ductal remnant can be clamped with a small vascular clamp to allow more definitive proximal flow if patent ducts do exist.

If no proximal contrast reaches the liver, the distal ductal remnant can be clamped with a small vascular clamp to allow more definitive proximal flow if patent ducts do exist. No passage of contrast into the liver confirms the diagnosis of biliary atresia (Fig. 23-7). Intrahepatic flow into anatomically correct ducts, even when they are small, is inconsistent with biliary atresia, and Kasai portoenterostomy is not indicated in such scenarios.

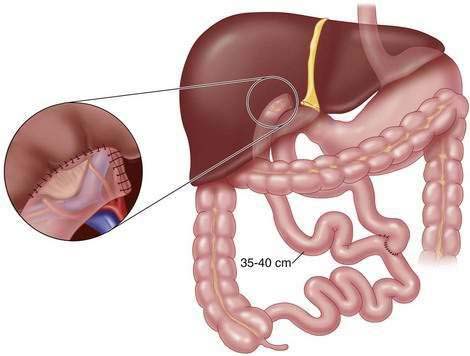

No passage of contrast into the liver confirms the diagnosis of biliary atresia (Fig. 23-7). Intrahepatic flow into anatomically correct ducts, even when they are small, is inconsistent with biliary atresia, and Kasai portoenterostomy is not indicated in such scenarios. In cases of diminutive size of the distal bile duct resulting in increased resistance to bile flow (see Fig. 23-7), we would elect standard Roux-en-Y portoenterostomy. In selected cases in which distal duct patency exists and low-resistance bile outflow is demonstrated by a normal-sized distal bile duct, a “gallbladder Kasai” can be used as an alternative to the conventional Roux-en-Y reconstruction.

In cases of diminutive size of the distal bile duct resulting in increased resistance to bile flow (see Fig. 23-7), we would elect standard Roux-en-Y portoenterostomy. In selected cases in which distal duct patency exists and low-resistance bile outflow is demonstrated by a normal-sized distal bile duct, a “gallbladder Kasai” can be used as an alternative to the conventional Roux-en-Y reconstruction.Operative Procedure Step 2: Kasai Portoenterostomy

Closing

Step 4: Postoperative Care

Step 5: Pearls and Pitfalls

Balistreri WF. Neonatal cholestasis. J Pediatr. 1985;106:171-184.

Bates MD, Bucuvalas JC, Alonso MH, et al. Biliary atresia: pathogenesis and treatment. Semin Liver Dis. 1998;18:281-293.

Chiba T. Japanese biliary atresia registry. In: Ohi R, editor. Biliary atresia. Tokyo: ICOM Associates, 1991.

Hasegawa T, Kimura T, Sasaki T, et al. Indication for redo hepatic portoenterostomy for insufficient bile drainage in biliary atresia: re-evaluation in the era of liver transplantation. Pediatr Surg Int. 2003;19:256-259.

Kasai M. Treatment of biliary atresia with special reference to hepatic porto-enterostomy and its modifications. Prog Pediatr Surg. 1974;6:5-52.

Kasai M, Suzuki H, Ohashi E, et al. Technique and results of operative management of biliary atresia. World J Surg. 1978;2:571-579.

Kimura K, Tsugawa C, Kubo M, et al. Technical aspects of hepatic portal dissection in biliary atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 1979;14:27-32.

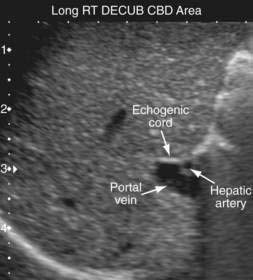

Kotb MA, Kotb A, Sheba MF, et al. Evaluation of the triangular cord sign in the diagnosis of biliary atresia. Pediatrics. 2001;108:416-420.

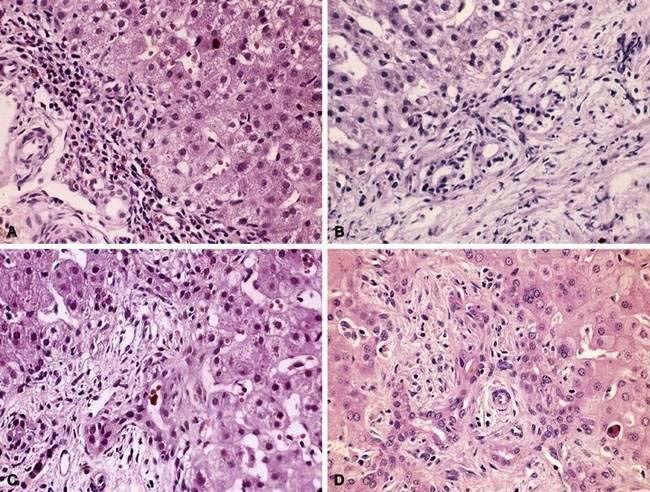

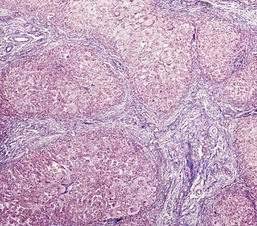

Lefkowitch JH. Biliary atresia. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:90-95.

Luo Y, Zheng S. Current concept about postoperative cholangitis in biliary atresia. World J Pediatr. 2008;4:14-19.

Meyers RL, Book LS, O’Gorman MA, et al. High-dose steroids, ursodeoxycholic acid, and chronic intravenous antibiotics improve bile flow after Kasai procedure in infants with biliary atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:406-411.

Miyano T. Biliary tract disorders and portal hypertension. In: Ashcraft KW, Holcomb GW, Murphy JP, editors. Pediatric Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005:586-608.

Ryckman FC. Biliary atresia (Hepatoportoenterostomy. In: Baker RJ, Fischer JE, editors. Mastery of surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:1213-1218.

Ryckman FC, Alonso MH, Bucuvalas JC, et al. Biliary atresia—surgical management and treatment options as they relate to outcome. Liver Transpl Surg. 1998;4:S24-S33.