Chapter 33 Best Treatment for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: What Do Current Systematic Reviews Tell Us?

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is a structural, lateral, rotated curvature of the spine of at least 10 degrees (using the Cobb measurement method) arising in otherwise normal children at or around puberty. The diagnosis is one of exclusion, made only when other causes of scoliosis, such as vertebral malformation, neuromuscular disorder, and syndromic conditions have been ruled out. Curvatures less than 10 degrees are viewed as a variation of normal because they have little potential for progression.

When defined as at least a 10-degree angle, epidemiologic studies estimate that 1% to 3% of the at-risk population (children aged 10–16 years) will have some degree of curvature, with most curves requiring no intervention.1,2

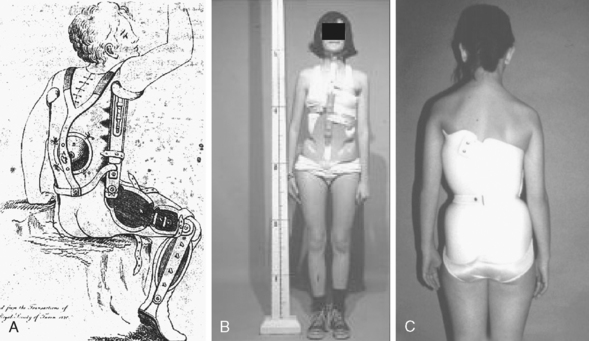

Despite the fact that idiopathic scoliosis has been studied and treated for many centuries, the lack of knowledge concerning the etiopathogenesis of the condition has limited clinicians’ ability to prevent the disease. They are therefore left to interventions aimed at secondary prevention, where the goal is to avoid the negative side effects of the established disease. And although operative interventions have become safer and more effective at restoring normal anatomy since the 1950s, one could argue that few, if any, advances have been made in nonoperative treatment. Roach3 reports that as early as 400 BC, Hippocrates recognized the condition and used a system of intermittently applied forces to apply distraction and lateral pressure to reduce the deformity (Fig. 33-1, A). The Milwaukee brace and, more recently, thoracolumbosacral orthosis (TLSO) use these same principles to effect curve reduction (see Figs. 33-1, B and C). This lack of advancement would be acceptable if clinicians were certain that the interventions actually demonstrated the ability to achieve anatomic and quality-of-life goals of the patient. However, this is not necessarily the case. Curves continue to progress to the point where only surgery can correct the deformity, and prevent future progression and possible pulmonary compromise; patients continue to report dissatisfaction with daily bracing and exercise regimens, and as adults, many face back pain, alterations in body image, and pulmonary impairment. Therefore, in light of these shortcomings, it is imperative that clinicians and patients have access to evidence concerning the effectiveness and side effects of these treatments, so they can knowledgeably make decisions based on their own personal risk/benefit ratios. Systematic reviews, the explicit combination of findings from multiple studies, can provide the reliable and accurate conclusions about effectiveness that patients should receive to make informed decisions. This chapter summarizes the existing systematic reviews of nonoperative treatments for AIS and discusses the practical implications of the findings.

SUMMARY OF REVIEWS

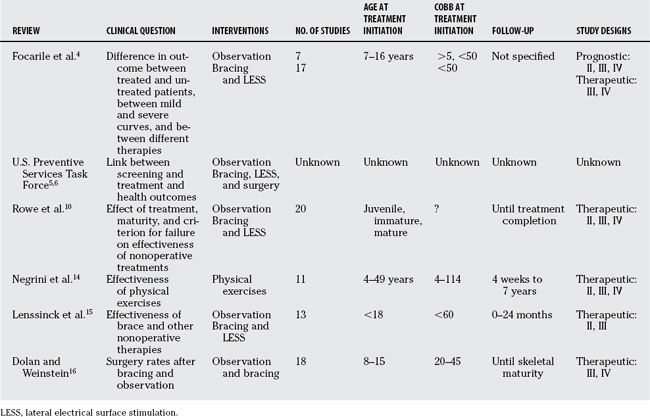

We conducted a search of the Cochrane, Medline, DARE (Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects), and ACP Journal Club databases for meta-analyses and systematic reviews of AIS treatment. After excluding articles concerning operative treatments, the search yielded six studies. The major objectives of these studies included effectiveness of mass screening, exercises, bracing, observation, and electrical stimulation. All but one were quantitative reviews that attempted to combine outcome rates across studies. Table 33-1 summarizes the studies that were included in each of the reviews.

Effectiveness of Nonsurgical Treatment for Idiopathic Scoliosis

The first systematic review of nonoperative treatment for AIS was conducted by an Italian group and published in 1991.4 This study was conducted to gather evidence for or against routine screening for AIS, assuming that early detection must be justified by early, effective treatment. Thus, the question: Are available nonoperative treatments effective in changing the natural history of the condition?

The authors conducted a literature search of the Medline database, searching for English-language articles published between 1975 and 1987. Keywords included “therapy,” “scoliosis,” “random allocation,” “natural history,” “prevention,” “control,” “occurrence,” “mass screening,” “child,” “adolescent,” and “follow-up studies.” The search yielded 111 articles that were reviewed by 2 of the authors. Studies were combined into natural history and therapy studies. Criteria for including natural history studies were few; they required a radiograph at the beginning and end of treatment, criteria for progression, and the number of patients who progressed. Thus, seven studies were included in the final review. The therapy studies included those with patients whose curves were less than 50 degrees at treatment initiation, and 17 articles were included in the final review. The authors calculated the percentage of patients who progressed more than 5 degrees or did not respond favorably (finished treatment with a curve greater than 45 degrees or went on to surgery) and then derived a 95% confidence interval (CI) around the proportion for the individual natural history and treatment studies. In addition, pooled rates were developed by calculating the direct standardized ratio and 95% CI.

Screening for Idiopathic Scoliosis in Adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) released their recommendations for screening in 19965 and updated them in 2004.6 In 1996, they stated, “There is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against routine screening of asymptomatic adolescents for idiopathic scoliosis”6 partly because of the lack of convincing evidence that nonoperative treatment of curves detected early results in better health outcomes. In 2004, the USPSTF re-examined their recommendation in light of research published between 1994 and 2002, and attempted to answer several questions including: Is there new evidence that early treatments lead to better health outcomes if applied at an early stage?

The RCT compared studies of the effects of exercise alone, exercise and bracing combined, and exercise and electrical stimulation combined.7 The subjects were between 6 and 16 years old, with curves ranging from 15 to 45 degrees. After 12 weeks of treatment, overall improvement was found for all three groups, and no significant difference was found between the different combinations of treatments. The USPSTF also evaluated the results of two cohort studies. One was a long-term retrospective study of patients treated with bracing or surgery, or both, compared with an age-matched, population-based control group.8 The follow-up occurred an average of 22 to 23 years after completion of treatment. Both patient groups responded well in terms of curve progression, and no difference in degenerative spine changes was found between the braced and surgical group, although both groups had more degenerative disc changes than the control group. The USPSTF also considered a multinational, controlled study of bracing, observation, and electrical stimulation.9 Treatment was considered successful if the curve progressed less than 6 degrees by the time the subjects were 16 years of age. A highly significant effect favored bracing over the other 2 treatments. One meta-analysis was available to the USPSTF.10 The analysis (more fully described later in this chapter) included only observational studies, of which only 1 included a control group. The definition of failure was 3 to 10 degrees of progression. Overall, the primary authors conclude that bracing for 23 or more hours per day is the superior treatment for AIS to prevent curve progression.

Given these new studies, the 2004 USPSTF summary5 states they could find no new evidence concerning the effectiveness of screening. They also report that conclusions about treatments are limited by the mixed quality of treatment outcomes studies, including inadequate adjustment for confounding factors, and the lack of health outcomes data. The evidence was rated as fair, defined as “sufficient to determine effects on health outcomes, but the strength of the evidence is limited by the number, quality or consistency of the individual studies, generalizability to routine practice or indirect nature of the evidence on health outcomes.”5 Their recommendation carries a grade of D, recommending against routine screening of asymptomatic patients because of at least fair evidence that screening is ineffective or that harms outweigh the benefits. This conclusion represents the current (U.S.) consensus not to screen routinely for scoliosis in schools, and thus informs public health practice. The question regarding the effectiveness of brace treatment in clinical practice is secondary, although crucial, because screening cannot be justified unless early, effective treatment is available. Recent evidence suggesting that bracing might be effective9,10 was incorporated into the review. Evidence for the clinical effectiveness of brace treatment was not compelling enough to support screening to brace early. Again, insufficient evidence is provided in this review to inform the clinical decision on whether to brace.

Meta-analysis of the Efficacy of Nonoperative Treatments for Idiopathic Scoliosis

Rowe and coworkers,10 as charged by the Prevalence and Natural History Committee of the Scoliosis Research Association, used meta-analysis to determine whether bracing substantially reduces the number of curves that progress to the degree where surgical intervention is warranted. They were interested in the nonoperative options of observation, bracing, and LESS.

Rowe and coworkers10 found that the unweighted rate of success in the bracing studies ranged from 57%11 to 100%,12,13 and the weighted mean rate of success was 92%. For the LESS studies, unweighted success rates ranged from 22% to 64%, and the weighted mean rate was 39%. In the one study of observation, the rate of success was 49%. The definition of outcome was found to influence the results: When defined as less than 6 degrees, the success rate was 68%, almost identical as the success rate when defined as progression of less than 10 degrees (67%). However, in the 5 bracing studies where success/failure was undefined, the success rate was 97%. This indicates that the results of the studies where the outcome was not defined inflated the success rate when weighted and averaged over studies.

The authors also found curves were less likely to progress the more mature the patient was at the beginning of treatment, and that wearing the brace for 23 hours/day was significantly more successful than 16- or 8-hour (Charleston brace) regimens. Overall, they conclude that the results of this meta-analysis support the efficacy of bracing compared with LESS and observation only. This review was an attempt to answer a direct clinical question about whether to brace and comes to a conclusion supporting bracing. Strengths of the review include the quantitative pooling of data from different studies. Limitations include the search methodology (beginning with a textbook) being nonstandard, the source articles being of low and variable quality, and hence more difficult to pool, and the failure to account for publication bias. In addition, the pooling of natural history data from one source of patients with treatment data from other cities at other times is inextricably biased. Applying this review to clinical practice would mean bracing immature patients with small curves, but on evidence with sufficient documented limitations and potential biases that it would not meet methodologic standards for prescribing a drug treatment, for example.

Physical Exercises as a Treatment for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Systematic Review13

The objective of a review by an Italian group was to assess the effectiveness of physical exercises for AIS in terms of delaying or preventing the need for bracing and in keeping the curve less than 30 degrees (mild scoliosis).13 Figure 33-2. shows a patient with scoliosis performing a postural exercise to avoid compression in the concave side of the curve.

(From Weiss HR, Weiss G, Petermann F: Incidence of curvature progression in idiopathic scoliosis patients treated with scoliosis in-patient rehabilitation (SIR): An age- and sex-matched controlled study. Pediatr Rehabil 6:23–30, 2003, reprinted with permission of the publisher (Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals).

Effect of Bracing and Other Conservative Interventions in the Treatment of Idiopathic Scoliosis in Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials

Lenssinck and coauthors’15 review from a group of physical therapists in the Netherlands begins by stating that there is a consensus about surgical treatment for the small group of patients with curves exceeding 45 degrees, but that there is currently no systematic review of the effectiveness of conservative (i.e., nonoperative) care for AIS. They also deemed Rowe and coworkers’10 study as invalid because it does not meet the criteria for reviews set down by the Cochrane Collaboration. Therefore, the aim of their study was to evaluate the effectiveness of nonoperative care using the Cochrane criteria.

No statistical pooling was done because of the heterogeneity of the studies with regard to interventions, populations, and treatment duration. Overall, no statistical differences between groups within studies were found, but using a brace tended to result in the most frequent reduction of the curve. Lenssinck and coauthors’15 cite only 1 study with a statistically significant difference, Nachemson and Peterson,9 but conclude that this study was of low quality, and that the treatment assignment was not random. They also found no differences among braces or between bracing and LESS. They then conclude that the effectiveness of bracing and exercises is promising but not yet established. This review may again frustrate the practitioner by concluding that insufficient evidence has been reported in the literature to guide selection of either bracing or physical therapy treatment. The review attempted to uphold higher methodologic review standards rather than to draw a “pragmatic” conclusion. It underlines the current seeming paradox in systematic reviews—the higher the quality of the review itself, the lower the grade of recommendation it tends to make. This paradox exists in fields such as children’s orthopedics where RCTs are the exception rather than the norm in assessing the results of treatment.

Surgical Rates after Observation and Bracing for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: An Evidence-Based Review

Dolan and Weinstein’s16 review derived a pooled rate of the prevalence of surgery in untreated and braced patients, and attempted to evaluate the effect of certain known risk factors for curve progression on surgical rates. The authors attempted to mimic current indications for bracing by limiting the study to patients with curves between 20 and 45 degrees, and age between 8 and 15, and a Risser sign of 0, 1, or 2. Follow-up to skeletal maturity was also mandatory. Interventions included observation, TLSOs, and bending (nighttime) braces. Studies were limited to those reporting rates of surgery, recommended surgery or curves progressing to greater than 50 degrees.

Of 152 studies reviewed, only 18 met the inclusion criteria. In total, 15 studies reviewed bracing and 3 reviewed observation. Minor exceptions were made to the criteria to include 2 observation and five bracing studies. All studies were Level III comparison studies or Level IV case series. The sample size of the individual studies ranges from 15 to 319 (median sample size, 78). Surgical indications included progression, a curve greater than 45 degrees, or a curve greater than 50 degrees. Some studies took other characteristics into consideration, such as complaints of pain, deformity, and the wishes of the patient and family. The surgical rates in the observation studies ranged from 13%17,18 to 38%19 (pooled estimate, 22%; 95% CI, 16–29%). This rate was comparable with that found for the bracing studies, where rates ranged from 1%13 to 43%,20 for a pooled rate of 23% (95% CI, 20–24%). The authors state that comparing the surgery rates for observation and bracing shows no clear advantage to either approach, and that the practice of bracing patients with these characteristics to avoid surgery is supported by inconsistent or inconclusive studies. This review asks a clearly defined question: Does bracing decrease the surgical rate? Selecting only articles that contribute directly to that question (and therefore excluding many studies using radiographic progression as an end point), the answer to the question is that bracing does not decrease the rate of surgery among patients with AIS with Risser signs of 0 to 2. Pooling Level III and IV studies gives a larger sample but does not increase the level of evidence. Therefore, this study could be interpreted as weak evidence supporting not using a brace in clinical practice or as additional evidence that the realistic conclusion to be drawn from the current literature is one of equipoise—that is, we simply do not know enough or have enough evidence to decide whether to use a brace.

METHODOLOGIC CONSIDERATIONS

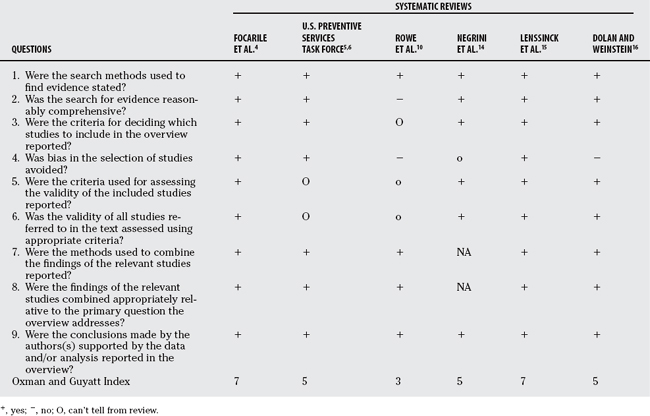

Just as individual studies can be biased or otherwise flawed, so can systematic reviews. First, the question asked by a review needs to be defined precisely so that only the appropriate primary studies will be included. Of the systematic reviews summarized here, all were designed to answer questions of effectiveness, but the USPSTF5,6 searched broadly to collect information about screening and subsequent treatment, whereas Dolan and Weinstein’s16 review specifically examined two treatment approaches and one outcome. The quality of a systematic review should be assessed as stringently as primary studies. Table 33-2 summarizes the reviews in terms of the Oxman and Guyatt Overview Quality Assessment Questionnaire (OQAQ) to access the scientific quality of the materials and methods leading up to the conclusions.21 First, the search methods used to find the primary studies should be stated explicitly and be comprehensive. The sources should be named (e.g., Medline, Embase), and the years covered by the search should be specified. In addition, the search must be comprehensive, demonstrated by a listing of keywords used in the search (OQAQ items 1 and 2). All the reviews in this chapter searched electronic databases, except for Rowe and coworkers,10 which included only articles from a textbook bibliography. Rowe and coworkers10 also included Nachemson and Peterson’s9 manuscript (before its peer review and publication) and an unpublished doctoral thesis,22 but it did not explicitly give the authors’ reasons for doing so. Notably, both of these articles had a relatively high rate of success and large sample size. The criteria for including and excluding primary studies should be explicit; in addition, more than one reviewer should decide independently which papers meet these criteria, and a consensus should be reached, to eliminate bias in selecting the materials (OQAQ items 3 and 4). In addition to finding all pertinent articles, reviewers should also make an effort to assess the validity of the primary articles. The criteria for validity (i.e., scoring system or level of evidence based on research design) should be mentioned and incorporated into decisions either concerning which papers to include or when analyzing the studies that are cited (OQAQ items 5 and 6). All authors note methodologic problems with the articles they include; only Lenssinck and coauthors15 limited their review to controlled studies. Rowe and coworkers10 rated each study according to a list of quality indicators. The methods used to combine the findings of the study should be stated and appropriate relative to the primary question (OQAQ items 7 and 8). None of the pooled results was weighted according to quality scores. Rowe and coworkers10 weighted their success rates according to sample size. The point estimate from a larger study is more precise than that from a smaller study; however, weighting by sample size does not ensure that studies with the most evidence for internal validity are given more impact than others. In addition, sensitivity analysis or some other method of evaluating the sensitivity of the pooled results to certain characteristics of the studies should be included. For example, Focarile and researchers4 found that retrospective studies (or those where the patients were selected for study) had greater rates of progression than prospective studies. Dolan and Weinstein16 note that including results of one study almost doubled the pooled surgical rate from the observational studies. Lastly, the numeric result and the conclusions must be interpreted with common sense and the context of the question being asked (OQAQ item 9). The reviewer must decide how the result should influence the care of an individual patient.21 All of the reviews except for the USPSTF5,6 and Rowe and coworkers10 acknowledge that their results do not support or deny the effectiveness of the treatments they reviewed. The USPSTF5,6 recommends against screening after they balanced the potential benefits and potential harms of both screening and early treatment. Rowe and coworkers10 recommend full-time bracing relative to part-time bracing, LESS, or observation, on the basis of statistical pooling of the data. And although, statistically, bracing does appear to be relatively effective, the authors did not take the poor quality of the studies into account, and they did not acknowledge the questionable reliability of the success and failure rates in the sole study reflecting the outcomes of observation. They additionally included multiple studies of bracing where the criteria for success were not explicitly defined, despite the fact that these rates were acknowledged to be among the greatest reviewed. The criteria for failure were based on Cobb angle progression rather than on surgical rate. Based on the OQAQ criteria and Oxman and Guyatt’s suggested scoring and interpretation of overall scientific quality21 (OQAQ item 10), scores for these reviews ranged from 310 to 7.4,15 A score of 1 to 4 points indicates extensive flaws, 5 or 6 points indicates minor flaws, and 7 points indicates minimal flaws. Based on this system, Rowe and coworkers’10 review is extensively flawed, and its recommendations should be questioned. Focarile and researchers’4 and Lenssinck and coauthors’15 reviews were the highest quality in this series, and as such, their recommendations should be considered the most valid and informative concerning treatment decisions.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

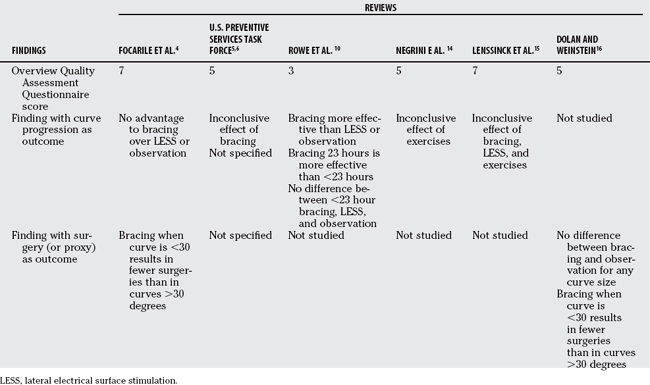

Clinicians looking to these studies for an answer to the question, “What is the best treatment for scoliosis?” could be rightfully frustrated. After many years of treating this condition, the research literature, both primary studies and systematic reviews, still lacks a clear consensus concerning the effectiveness of bracing, LESS, and exercises. In making a decision about treatment, the first step should be to clarify the goals of the patient, convey the pertinent findings together with the quality of the evidence behind the findings, discuss the possible side effects, and then to let the patient make the decision based on a personal risk/benefit ratio. Table 33-3 provides a guide to clinicians who wish to impart information from these reviews to their patients.

Preventing curve progression is a different goal from preventing surgery. Curve progression can occur without reaching the threshold (generally, 45–50 degrees) where there is a high risk for continued progression and of developing an unacceptable deformity that can be treated only by instrumentation and fusion. Therefore, if the patient’s goal is to prevent even a few degrees of progression, the clinician could relate the following information: No high-quality evidence has demonstrated an advantage of bracing over observation or any other nonoperative treatment to prevent progression. However, one low-quality systematic review10 suggests that bracing may be advantageous, but only if the brace is worn for 23 hours/day. The adverse effects of bracing include skin irritation and some risk for psychosocial problems such as self-consciousness; however, these problems are extre-mely variable, and some patients have no problems with the treatment at all.

If the patient is comfortable with the risk for some curve progression but is more concerned with preventing progression to the point of surgery, then the following information could be given: Only two systematic reviews in the literature examine the rate of surgery after bracing and observation. One was of high quality,4 and the other was of adequate quality.16 The higher quality study suggests that bracing significantly decreases the risk for surgery when started early, that is, when the curve is less than 30 degrees, compared with starting for a more severe curve. The study of lesser quality found the same advantage to bracing early, but overall did not find any difference in surgical rates, for any curve size, between bracing and observation. Bracing has been associated with some adverse effects. Observation is a difficult choice, especially when the impulse is to seek active treatment. Patients who watch and wait may feel remorse if surgery is advised, because of their decision not to treat.

DISCUSSION

Systematic reviews represent the best sources of quantitative information for making evidence-based choices in medicine. Also, they are especially needed in an area such as AIS for several reasons. The sample size available to any one researcher is generally too small to make a definitive statement about effectiveness, especially when subgroup analysis is necessary to evaluate outcomes according to risk factors such as curve size, maturity, and curve location. The practice of bracing around the world is anything but standardized; multiple types of braces are used in North America alone, as well as the different types used in Europe. In addition, some countries such as Germany, Spain, and Italy23,24 tend to begin treatment with exercises, followed by a combination of exercises and bracing if the curve progresses. This variability in practice requires large, multinational efforts with clearly specified treatment regimens to discern the relative merits of each treatment program. The reviews in this chapter illustrate the disparate findings in the primary literature. For example, the range of surgical rates after bracing in the Dolan and Weinstein16 review was 1% to 43%; not included in their review were two recent articles, one with a surgical rate of 0%25 to 76%.26 But perhaps the most compelling reason for systematic reviews in this population is the costs to the healthcare system and to families.

Mass screening for AIS diverts resources from other public health programs at the same time that it creates unnecessary costs through referral of children with “schooliosis.” Observation can be difficult for families who want to actively treat the condition, even if the risk of surgery is not definitely decreased. Braces are expensive, both in terms of money and psychosocial costs to the family. In some cases, patients perceive the brace to be more deforming than the anatomy they are trying to correct. Currently, the USPSTF review5,6 continues to find insufficient evidence that early diagnosis produces net benefit, and thus does not recommend routine school screening for scoliosis, in part because the lack of evidence for the effectiveness of early clinical treatment.

Regarding clinical treatment, insufficient evidence exists to support physical therapy as an effective modality when curve progression is the desired outcome.14,15 Bracing is more complicated. One meta-analysis10 concludes that bracing is effective (92% “success” rate with bracing, 49% “success” rate with control) by pooling patient data from Level II, III, and IV studies of varying quality. This conclusion was based on either Cobb angle progression or unspecified criteria for failure. The review itself was done in a manner quite differently from that currently accepted. Two additional meta-analyses5,16 with strict search and inclusion criteria have failed to support bracing. In the case of the Dolan and Weinstein16 review, the question was, What is the surgical rate with (23%) and without (22%) bracing? This well-defined outcome was addressed only in level III and IV studies. In the case of the Lennsinck and coauthors’15 review, the application of quality criteria to the included studies limited the ability of the reviewers to draw any firm conclusions about the effectiveness of bracing. For the clinician, the lesson is that a single meta-analysis does not conclusively answer a clinical question. Meta-analyses differ in quality and detail, and all are limited by the availability and quality of published clinical evidence. Where level III and IV studies predominate, systematic reviews may produce results that contradict each other or that are inconclusive, or both. Such is the state of knowledge regarding bracing: The balance of published evidence neither supports nor prohibits using a brace to treat scoliosis in the growing child. Table 33-4 provides a summary of recommendations.

| STATEMENT | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENATION | REFERENCES |

|---|---|---|

1 Parent S, Newton PO, Wenger DR. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Etiology, anatomy, natural history, and bracing. Instr Course Lect. 2005;54:529-536.

2 Shindle MK, Khanna AJ, Bhatnagar R, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Modern management guidelines. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2006;15:43-52.

3 Roach JW. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Nonsurgical treatment. In: Weinstein SL, editor. The Pediatric Spine. New York: Raven Press; 1994:497-510.

4 Focarile FA, Bonaldi A, Giarolo MA, et al. Effectiveness of nonsurgical treatment for idiopathic scoliosis. Overview of available evidence. Spine. 1991;16:395-401.

5 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Idiopathic Scoliosis in Adolescents: Recommendation Statement [Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality], June 2004. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/3rduspstf/scoliosis/scoliors.htm. Accessed July 3, 2008.

6 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Review article. JAMA. 1993;269:2667-2672.

7 el-Sayyad M, Conine TA. Effect of exercise, bracing and electrical surface stimulation on idiopathic scoliosis: A preliminary study. Int J Rehab Res. 1994;17:70-74.

8 Danielsson AJ, Nachemson AL. Radiologic findings and curve progression 22 years after treatment for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Comparison of brace and surgical treatment with matching control group of straight individuals. Spine. 2001;26:515-525.

9 Nachemson AL, Peterson LE. Effectiveness of treatment with a brace in girls who have adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. A prospective, controlled study based on data from the Brace Study of the Scoliosis Research Society. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:815-822.

10 Rowe DE, Bernstein SM, Riddick MF, et al. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of non-operative treatments for idiopathic scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:664-674.

11 Green NE. Part-time bracing of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68:738-742.

12 Edmonsson AS, Morris JT. Follow-up study of Milwaukee brace treatment in patients with idiopathic scoliosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1977:58-61.

13 Ylikoski M, Peltonen J, Poussa M. Biological factors and predictability of bracing in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1989;9:680-683.

14 Negrini S, Antonini G, Carabalona R, et al. Physical exercises as a treatment for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. A systematic review. Pediatr Rehabil. 2003;6:227-235.

15 Lenssinck ML, Frijlink AC, Berger MY, et al. Effect of bracing and other conservative interventions in the treatment of idiopathic scoliosis in adolescents: A systematic review of clinical trials. Phys Ther. 2005;85:1329-1339.

16 Dolan LA, Weinstein SL. Surgical rates after observation and bracing for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: An evidence-based review. Spine. 2007;32:S91-S100.

17 Goldberg CJ, Dowling FE, Hall JE, et al. A statistical comparison between natural history of idiopathic scoliosis and brace treatment in skeletally immature adolescent girls. Spine. 1993;18:902-908.

18 Goldberg CJ, Moore DP, Fogarty EE, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: The effect of brace treatment on the incidence of surgery. Spine. 2001;26:42-47.

19 Fernandez-Feliberti R, Flynn J, Ramirez N, et al. Effectiveness of TLSO bracing in the conservative treatment of idiopathic scoliosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15:176-181.

20 Little DG, Song KM, Katz D, et al. Relationship of peak height velocity to other maturity indicators in idiopathic scoliosis in girls. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:685-693.

21 Bhandari M, Morrow F, Kulkarni A, Tornetta P. Meta-analyese in orthopaedic surgery. A systematic review of their methodologies. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:15-24.

22 Styblo K. Conservative Treatment of Juvenile and Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Leiden, The Netherlands: Rijksuniversiteit te Leiden, 1991.

23 Negrini S, Aulisa L, Ferraro C, et al. Italian guidelines on rehabilitation treatment of adolescents with scoliosis or other spinal deformities. Eura Medicophys. 2005;41:183-201.

24 Weiss HR, Negrini S, Rigo M, et al. Indications for conservative management of scoliosis (guidelines). Scoliosis. 2006;1:5.

25 Danielsson AJ, Hasserius R, Ohlin A, et al. A prospective study of brace treatment versus observation alone in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A follow-up mean of 16 years after maturity. Spine. 2007;32:2198-2207.

26 Janicki JA, Poe-Kochert C, Armstrong DG, et al. A comparison of the thoracolumbosacral orthoses and providence orthosis in the treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Results using the new SRS inclusion and assessment criteria for bracing studies. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27:369-374.