18

Benign ulceration of the stomach and duodenum and the complications of previous ulcer surgery

Management of refractory peptic ulceration

Non-HP-related refractory ulceration

Ingestion of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be re-evaluated. Surreptitious aspirin ingestion has been observed and if suspected can be established by assay of plasma salicylate levels. Any other factor that may be facilitating ulceration and impairing healing, such as intercurrent disease and smoking, should be sought and eliminated where possible. Diseases associated with peptic ulceration are chronic liver disease, hyperparathyroidism and chronic renal failure, particularly during dialysis and after successful transplantation. Smokers are more likely to fail both medical and, indeed, surgical ulcer treatment. Smoking impairs the therapeutic effects of antisecretories, may stimulate pepsin secretion and promotes reflux of duodenal contents into the stomach. Smoking increases the harmful effects of HP, and increases the production of free radicals, endothelin and platelet-activating factor. Smoking also affects the mucosal protective mechanisms by decreasing gastric mucosal blood flow and inhibiting gastric prostaglandin generation and the secretion of gastric mucous, salivary epidermal growth factor, duodenal mucosal bicarbonate and pancreatic bicarbonate.2 Stopping smoking is an important, yet often ignored, first step to allow effective ulcer treatment.

Elective surgery for peptic ulceration

Operations for refractory duodenal ulcers: There is no good evidence on which to base the decision of operation in cases of resistant ulceration in the modern era. Intuitively, one might predict a poor result with HSV alone since its success rate historically was less than that of modern medical treatment. It seems likely that resection of the antral gastrin-producing mucosa and either resection or vagal denervation of the parietal cell mass is necessary. The operations that could be considered include the following:

• Selective vagotomy and antrectomy. Selective denervation is preferred because of a lower incidence of side-effects. It is not an easy procedure; in particular, the dissection around the lower oesophagus and cardia has to be done very carefully. The vagotomy should be performed before the resection and tested intraoperatively. The reconstruction should either be a gastroduodenal (Billroth I) anastomosis or a Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy. The latter is associated with fewer problems with bile reflux into the gastric remnant and oesophagus, but a higher risk of stomal ulceration and so at least a two-thirds gastrectomy is advised.

• Subtotal gastrectomy. Removal of a large part of the parietal cell mass is sound in theory and indeed ulcer recurrence after this operation is unusual. However, there is an incidence of postprandial symptoms, and in particular epigastric discomfort and fullness that can limit calorie intake. Importantly, there is a high incidence of long-term nutritional and metabolic sequelae that require lifelong surveillance and can be difficult to prevent, although this is mainly in women.

• Pylorus-preserving gastrectomy. This operation involves highly selective vagotomy with resection of about 50% of the parietal cell mass and the antral mucosa, but preserving the pyloric mechanism and the vagus nerves to the distal antrum and pylorus. There is some evidence that this may be a superior technique with fewer sequelae compared to the traditional approaches.3 Comparable results of the technique used in the context of treatment of early gastric cancer confirm a good long-term functional result.4

Operations for refractory gastric ulcers: There are no reliable data on which to base a recommendation for surgical treatment of refractory gastric ulcers. HSV is not recommended for pre-pyloric ulcers since they follow the same pattern as described for duodenal ulceration. The choice of operation for a more proximal ulcer, often along the lesser curve and often associated with atrophic gastritis, is between excision of the ulcer with HSV or partial gastrectomy. The recurrence rate is higher after HSV/excision, but the operative mortality is lower and side-effects fewer after this procedure.

Zollinger–Ellison syndrome (ZES)

Pathology

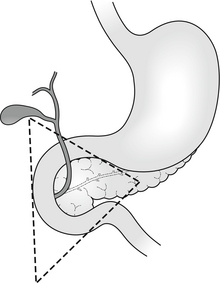

Although originally described as a pancreatic endocrine tumour, the definition has also come to include extrapancreatic gastrin-secreting tumours. The majority of tumours lie within an area defined by the junction of the cystic and common bile ducts superiorly, the junction of the second and third portions of the duodenum inferiorly, and the junction of the neck and body of the pancreas medially: the ‘gastrinoma triangle of Stabile’5 (Fig. 18.1). Where the condition is due to a pancreatic tumour, in two-thirds of cases the tumour will be multifocal within the pancreas.6 At least two-thirds will be histologically malignant. One-third will already have demonstrable metastases by the time of diagnosis.7 The most common extrapancreatic site is in the wall of the duodenum. Less frequently (6–11% of cases) ectopic gastrinoma tissue has been identified in the liver, common bile duct, jejunum, omentum, pylorus, ovary and heart.8 These extrapancreatic tumours rarely metastasise to the liver and, even though they do metastasise just as frequently to regional lymph nodes, they tend to have a better prognosis than primary pancreatic tumours.

One-quarter of patients with ZES have other endocrine tumours as part of a familial multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN-1) syndrome, particularly hyperparathyroidism.7 This group of patients has a much worse prognosis than sporadic ZES, in part due to the multifocal nature of the disease.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis may be confirmed by paradoxical fasting hypergastrinaemia associated with gastric acid hypersecretion. Hypergastrinaemia may be expected to occur in cases of achlorhydria such as ingestion of antisecretory drugs, postvagotomy, pernicious anaemia, atrophic gastritis, antral G-cell hyperplasia or gastric outlet obstruction. Hypergastrinaemia is also associated with a retained antrum after a Billroth II/Polya-type gastrectomy where a small cuff of antrum has been included in the ‘duodenal’ closure (if a retained antrum is suspected, technetium pertechnetate scan may be useful in identifying the antral mucosa). If there is diagnostic uncertainty or the basal serum gastrin level is marginal, dynamic assay of serum gastrin following secretin (or alternatively calcium or glucagon) provocation may be required. Gastrin response to a standard meal helps to differentiate hypergastrinaemia due to antral G-cell hyperplasia, which will result in an increase in serum gastrin levels, while no response would be expected in cases of gastrinoma. Serum chromogranin A, a non-specific marker for neuroendocrine tumours, should also be measured.9

Tumour localisation

Tumours may be localised initially by computed tomography (CT). This may also identify metastatic disease. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is highly accurate in the localisation of pancreatic tumours and gastrinomas in the duodenal wall as small as 4 mm. Octreotide scan and selective arterial secretagogue injection (SASI) testing are the most reliable approaches to localising gastrinomas. Liver metastases can frequently be detected by conventional imaging, but octreotide scan has proved a more sensitive investigation that may prevent unnecessary surgical exploration. SASI involves selective catheterisation of the feeding arteries of the duodenum and pancreas and the hepatic veins. Secretin is injected in turn into the splenic, gastroduodenal (GDA) and superior mesenteric (SMA) arteries. Corresponding hepatic venous gastrin levels are measured and allow identification of the main feeding vessel. More precise localisation can be achieved by more peripheral cannulation of the SMA and GDA or different points along the splenic artery. The test has greater than 90% sensitivity and specificity for preoperative tumour localisation.10

Surgery for ZES

The surgical management of ZES is characterised by controversy and little evidence. Historically, the debate centred around the radicality of surgical approaches to eliminate end organ acid production such as total gastrectomy. This is generally accepted, as unnecessary given that adequate acid suppression can usually be achieved with proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs), albeit at much higher doses than those usually recommended. How aggressively surgery should be pursued for the gastrinoma itself became the next area of controversy. With adequate acid suppression, patients may be rendered asymptomatic and the natural history of the gastrinoma tended to one of only very slow progression. Nevertheless, 60–90% of gastrinomas are reported to be malignant and some do have a more aggressive course. It became more acceptable to consider resection, as 30–50% with sporadic disease may be cured or at least have a reduced rate of development of liver metastases. Whether that should be local enucleation or a wider resection remains controversial. In the past many would say that patients with MEN-1 and those with liver metastases should not be treated surgically. Nevertheless, impressive results have been reported even in the former group and there is evidence that surgical resection of metastatic liver disease does offer long-term survival, even where resection may be incomplete. One of the largest series has shown that surgical exploration and resection resulted in excellent long-term results, with a 15-year disease-related survival rate of 98% compared to 74% for non-operated cases.11

Surgical exploration when preoperative investigations have failed to precisely localise a tumour is now a less frequent problem, particularly in specialist centres with access to SASI and octreotide scan. Nevertheless, a laparotomy will detect a third more gastrinomas than even octreotide scan. If surgical exploration is performed then the pancreas must be mobilised along its entire length, inspected, palpated and if the facilities are available re-scanned intraoperatively by endoluminal or standard ultrasound. Palpation of the duodenal wall will identify 61% of duodenal gastrinomas. Duodenal transillumination by endoscopy will improve detection to 84% and duodenotomy identifies the remaining cases.12 If no gastrinoma is found in the usual locations, other ectopic sites should be examined carefully. Resection of these primary ectopic tumours can sometimes lead to durable biochemical cures. Gastrinomas may be identified in 96% of surgical explorations if these approaches are adopted.11 With the use of SASI in particular, though a tumour cannot be precisely localised, it may be sufficiently ‘narrowed down’ to allow a limited pancreatic and/or duodenal resection.10 The intraoperative secretin test in which gastrin levels in response to secretin are measured before and after resection can be useful in assessing the effectiveness of resection.

Emergency management of complicated peptic ulcer disease

Perforation

Conservative management

Study of the natural history of perforated peptic ulcers suggests that they frequently seal spontaneously by omentum or adjacent organs and that, particularly when this occurs rapidly, contamination can be minimal. Taylor showed that the mortality in his series of patients with peptic ulcer disease was half that of the contemporary (pre-1946) reported mortality for perforation treated surgically.14 Conservative treatment today consists of parenteral broad-spectrum antibiotics, intravenous acid antisecretories, intravenous fluid resuscitation and nasogastric aspiration. In addition, water-soluble meal and limited follow-through is recommended to confirm that the leak has sealed. CT is becoming increasingly used in the diagnosis of acute abdominal pain and the degree of fluid contamination may also serve as a useful guide as to whether peritoneal lavage or drainage is necessary.

Surgery

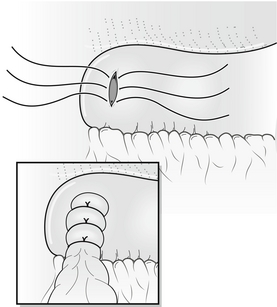

In most cases the treatment of choice for patients with perforation of the duodenum is still laparotomy, peritoneal lavage and simple closure of perforation, usually by pedicled omental patch repair (Fig. 18.2). The routine use of drains is unnecessary and may in fact increase morbidity. This simple treatment is safe and effective in the long term, when combined with pharmacological acid suppression. Ninety per cent of perforations are associated with HP infection,18 and HP eradication further significantly reduces the risk of ulcer recurrence.19

In cases of ‘giant’ perforation, where the defect measures 2.5 cm or more, partial gastrectomy with closure of the duodenal stump should be considered (see also management of bleeding from giant duodenal ulcer below). Alternatively, in situations where the clinical situation or expertise dictates more expeditious surgery, the duodenal perforation should be closed as well as possible around a large Foley or T-tube catheter to create a controlled fistula. This can be combined with venting gastrototomy and feeding jejunostomy.20 The advances in understanding of the medical treatment of peptic ulcer disease together with the decrease in experience of elective antiulcer surgery have made the argument for definitive ulcer surgery in the emergency setting almost untenable.

Although laparoscopic treatment of peptic ulcer perforation was first reported in 199021 and many excellent series have been reported since, a European population study demonstrated that the proportion of cases performed laparoscopically is as low as 6%,22 and even in centres with a specialist interest in laparoscopic surgery the proportion of cases completed laparoscopically is less than 50%.23

Bleeding

Surgery

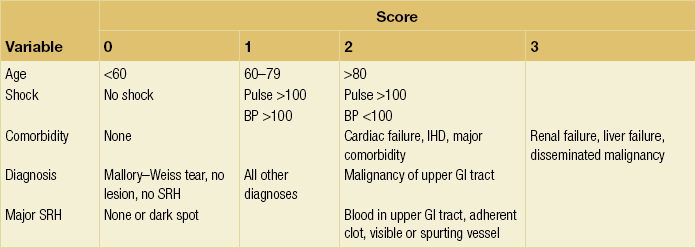

Surgical intervention should be anticipated where there is a significant risk of re-bleeding. Various scoring criteria have been suggested to predict risk of significant re-bleeding and death; one commonly used is the Rockall system (Table 18.1). In addition, the size of the ulcer (particularly > 2 cm) and its proximity to major vessels, such as the gastroduodenal ulcer on the posterior inferior wall of the duodenal bulb and the left gastric artery high on the lesser curve of the stomach, suggest a high risk of massive bleeding.

Table 18.1

Rockall scoring system for risk of re-bleeding and death after admission to hospital for acute gastrointestinal bleeding

A total score of > 3 is associated with good prognosis; < 8 is associated with high risk of death.

Bleeding duodenal ulcer: The first step is to make a longitudinal duodenotomy immediately distal to the pyloric ring. Haemostasis can be initially achieved by digital pressure. While it may be necessary to extend the duodenotomy through the pyloric ring, the pylorus should be preserved if at all possible. Older texts frequently assume that vagotomy is an integral part of ulcer surgery and recommend a larger pyloroduodenotomy, but this is usually not necessary. The stomach and duodenum should be cleared of blood and clots using suction to obtain optimal view of the bleeding site. If access is still difficult, kocherisation of the duodenum may help, along with drawing up of the posterior duodenal mucosa using Babcock’s forceps.

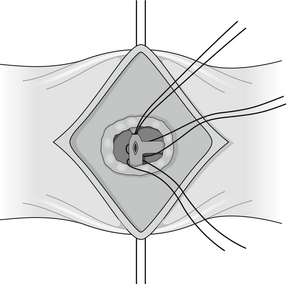

The actively bleeding or exposed vessel should be secured. Points of note in securing the vessel are the limited access, the proximity of underlying structures such as the common bile duct and the tough fibrous nature of the base of a chronic ulcer. In view of these problems, a small, heavy, round-bodied or taper-cut semicircular needle with 0 or No. 1 suture material should be used. The argument of absorbable versus non-absorbable sutures is irrelevant: the sutures probably slough off as the ulcer heals. Securing bleeding from the gastroduodenal artery may involve a horizontal mattress ‘U-stitch’ to incorporate posterior and medial perforating vessels (Fig. 18.3).

Figure 18.3 Suture control of bleeding from gastroduodenal artery illustrating the ‘U-stitch’ incorporating any perforating vessels.

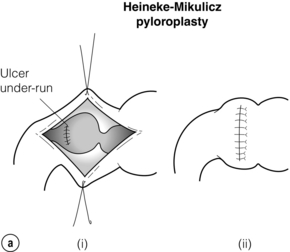

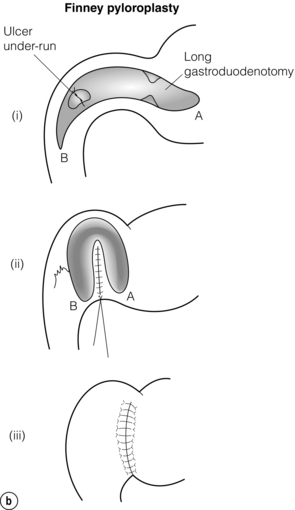

The duodenotomy may be closed longitudinally. If vagotomy has been performed the pyloric ring should be divided and the duodenotomy closed transversely to create a Heineke–Mikulicz pyloroplasty (Fig. 18.4a). If transverse closure is difficult because of the length of the duodenotomy, longitudinal closure may be performed and a gastrojejunostomy considered. Alternatively, a Finney pyloroplasty may be fashioned (Fig. 18.4b).

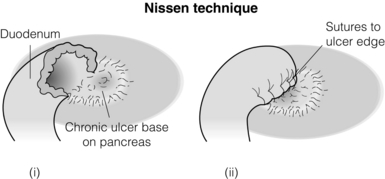

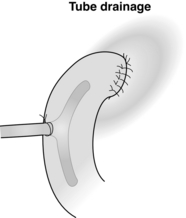

In a giant ulcer, the first part of the duodenum may be virtually destroyed and, once opened, impossible to close. In this situation it is necessary to proceed to partial gastrectomy. The right gastric and right gastroepiploic arteries are divided. The stomach is disconnected from the duodenum by a combination of blunt and sharp dissection. Antrectomy is perfomed and continuity restored by a gastrojejunostomy. The duodenal stump can then be closed. Although this can be achieved by pinching the second part of the duodenum away from the ulcer to allow conventional closure, this is probably more safely achieved by the technique of Nissen (Fig. 18.5). The duodenal stump is drained by either a tube or Foley catheter either through the duodenal suture line or more securely though the healthy sidewall of the second part of the duodenum (Fig. 18.6).

Bleeding gastric ulcer: The precise site of bleeding should already have been identified endoscopically. If not, intraoperative endoscopy and careful palpation of the stomach for induration should identify the site of the bleeding ulcer. If there is still doubt a generous incision should be made across the pylorus and duodenum, followed by a more proximal gastrotomy if the source of bleeding is still not clear. Most chronic gastric ulcers are at the incisura or in the antrum. The traditional treatment for such ulcers that fail endoscopic therapy is partial gastrectomy. Some groups have advocated simple under-running of bleeding gastric ulcers. While this may be appropriate in selected cases with small bleeding gastric ulcers such as the Dieulafoy lesion, the only randomised trial to date (n = 129) suggests that this ‘conservative’ approach has a higher mortality and is more likely to result in re-bleeding if used unselectively.35

Interventional radiology

There are no randomised controlled trials comparing surgery with transcatheter arterial embolisation as salvage treatment following endoscopy. Despite this, in some centres, interventional radiology has become the ‘gold standard’ intervention following failed endoscopy. Loffroy et al. looked at 15 studies that included 819 patients who had had failed endoscopic control of bleeding; 93% of cases were reported to have ‘technical success’.36 Of these, 67% had immediate cessation of bleeding. Of those that continued to bleed after initial treatment, half responded to a second embolisation. Overall, 20% of patients underwent salvage surgery. The overall mortality in these series was 28%. This seems disappointing and no better than one might expect from a series of bleeders salvaged by surgery. In fact, there was a wide variation between reported mortality in the series, which may indicate different levels of expertise, and case selection. The series were also collected over a 17-year period, during which time there has been considerable improvement in radiological technique. There have been two small retrospective comparisons involving a total of 161 patients.37,38 They showed that although the radiologically treated patients tended to be older and less fit, they had a comparable (26% vs. 21%) or lower (3% vs. 14%) mortality compared with the surgically treated group.

Pyloric stenosis

Resuscitation and medical therapy

Initial management should consist of aggressive parenteral fluid and biochemical restoration with nutritional and vitamin supplementation as necessary. Nasogastric intubation with a wide-bore tube allows gastric washout of undigested food and so reduces antral stimulation. Aggressive parenteral antisecretory therapy and Helicobacter pylori eradication, if appropriate, are used. In cases where the obstruction has been due to oedema and spasm, the situation can be expected to resolve once medical treatment has healed the ulcer.39 Dietary changes to decrease the fibre content while providing a high calorie and protein intake are important until ulcer healing has occurred. In cases where the obstruction is due to fibrosis and cicatrisation of a pyloric ulcer, some form of intervention will be necessary.

Endoscopic treatment

The group of patients who develop gastric outflow obstruction are generally elderly with established comorbidities and tolerate major surgery poorly. As a result, minimally invasive approaches such as endoscopic management are often more appropriate in the first instance. Initial reports of successful resolution of pyloric stenosis following endoscopic balloon dilatation were challenged due to the relatively high number of cases that ultimately required open surgery. Nevertheless, this remains a useful first-line endoscopic procedure that can be repeated on several occasions with good long-term results in up to 80% of patients.40

Surgery

Laparoscopic highly selective vagotomy with balloon dilatation has been attempted with some success in cases of pyloric stenosis. This has not been proven to be superior to dilatation and long-term acid suppression. Laparoscopic truncal vagotomy and gastroenterostomy has proven to be a technically feasible solution with good symptomatic, sustained response.41

Complications of previous ulcer surgery

Although elective surgery for benign ulcer disease is now rare, there remains a large cohort of patients operated on prior to the mid-1980s with a variety of surgical procedures, of whom a small percentage will develop further symptoms, some of which may be severely disabling. Although numerous clinical syndromes have been well described (Box 18.1), patients presenting with pure syndromes are uncommon. The majority presents with a mixed picture, but usually have a dominant symptom complex suggesting one main problem. This needs to be elucidated by a careful and detailed history of the clinical events occurring during a bad attack.

Preoperative evaluation

Radiology

Barium meal examination of the stomach is a useful adjunct where the anatomy remains unclear.

Enterogastric reflux

Surgical treatment

Reconstruction of the pylorus after pyloroplasty is a relatively straightforward operation. Having cleared the anteropyloroduodenal segment of all adhesions, the scar of the previous pyloroplasty is accurately opened. The pyloric ring is palpated and the scarred ends freshened if necessary. One approach is to make a small antral gastrotomy to allow the insertion of a size 12 or 14 Hegar dilator through the area of the pyloric reconstruction into the duodenum. Using a double-ended monofilament suture the pyloric ring is accurately opposed around the Hegar dilator before reapproximating the duodenum and antrum using a continuous serosubmucosal technique. Withdrawal of the Hegar dilator allows fingertip palpation of the reconstructed pylorus prior to closure of the antral gastrotomy. The overall results of pyloric reconstruction show that 80% of patients gain a satisfactory or good result,42 although in one study only half of the patients with enterogastric reflux had a satisfactory or good response.43

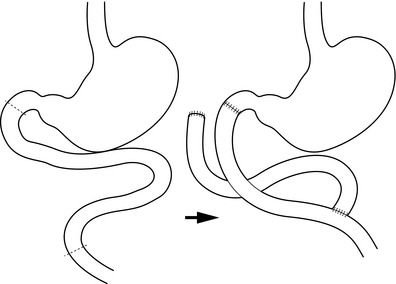

If enterogastric reflux is not relieved, then the duodenal switch operation would seem an appropriate further remedial procedure for patients whose symptoms necessitate further surgery44 (Fig. 18.7). Recent experience with this has shown good results, although acid suppression is needed to prevent jejunal ulceration.45

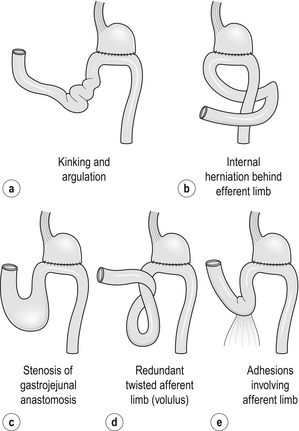

Chronic afferent loop syndrome

The afferent loop syndrome can only occur after gastrojejunostomy or a Billroth II-type reconstruction after partial gastrectomy. The condition is caused by intermittent postprandial obstruction of the afferent limb of the gastrojejunostomy. The clinical picture is very similar to that produced by enterogastric reflux (Table 18.2). The problem is rarely encountered if surgeons use a short afferent jejunal loop. The obstruction may be due to anastomotic kinking, adhesions, internal herniation, volvulus of the afferent limb or obstruction of the gastrojejunal stoma itself (Fig. 18.8). Once diagnosed, the treatment is always surgical. Conversion to a Billroth I anastomosis or a Roux-en-Y reconstruction of the afferent limb both produce good results.

Table 18.2

Differentiation between the chronic afferent loop syndrome and enterogastric reflux

| Chronic afferent loop syndrome | Enterogastric reflux |

| Meal-related pain – relieved by vomiting | Constant pain (worsened by eating) – not relieved by vomiting |

| Vomitus contains bile | Vomitus contains bile and food |

| Vomiting projectile | Vomiting non-projectile |

| Rarely associated with bleeding/anaemia | Bleeding/anaemia found in 25% of patients |

Dumping

The symptoms of early dumping can be divided into vasomotor and gastrointestinal, as shown in Box 18.2. In a severe attack, the vasomotor symptoms are usually experienced by the patient towards the end of a meal or within 15 minutes of finishing, and the gastrointestinal symptoms develop a little later, but usually within 30 minutes after eating.

Early dumping is associated with rapid gastric emptying leading to hyperosmolar jejunal content causing massive fluid shifts from the extracellular space into the lumen. This is associated with a significant fall in plasma volume. It is also known that plasma concentrations of several gut regulatory peptides are elevated in patients with the dumping syndrome, but it is not clear whether this is coincidental or causative. Late dumping symptoms are the result of reactive hypoglycaemia. Taking a careful history, delineating the vasomotor and gastrointestinal components, usually makes the diagnosis of the dumping syndrome. Where there is any doubt, the patient should be encouraged to keep a diary card recording the foods eaten and the symptoms that develop thereafter. A provocative test for assessing dumping syndrome can be used to confirm clinical suspicion. This test is a modification of the oral glucose tolerance test and involves the ingestion of 50 or 75 g glucose in solution after an overnight fast. Immediately before and up to 180 min after ingestion of this solution, the blood glucose concentration, haematocrit, pulse rate and blood pressure are measured at 30-min intervals. The provocative test is considered positive if late (120–180 min) hypoglycaemia occurs, or if an early (30 min) increase in haematocrit of more than 3% occurs. The best predictor of dumping syndrome seems to be a rise in the pulse rate of more than 10 b.p.m. after 30 min.46

Medical treatment

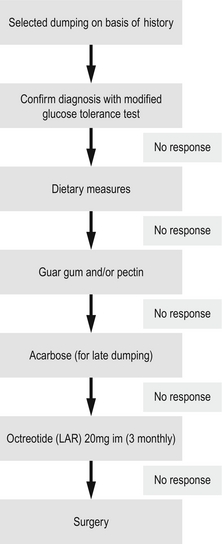

The majority of patients displaying the dumping syndrome can be managed satisfactorily by dietary manipulation. Reducing the carbohydrate content and restricting fluid intake with meals will help many of these patients. Avoiding extra salt and eating more frequent small meals may also be required. Lying down after eating helps to slow gastric emptying and may minimise symptoms. Guar gum, a vegetable fibre, is known to reduce postprandial hyperglycaemia in both normal and diabetic patients. In a small study of postgastric surgery patients it has been shown to prevent the dumping syndrome and increase food tolerance in the majority of patients.47 Pectin also delays gastric emptying but may precipitate diarrhoea. The use of acarbose, an alpha-glycoside hydrolase inhibitor, interferes with carbohydrate absorption and has been shown to help in patients with late dumping. Octreotide, given subcutaneously prior to eating, has been shown to significantly reduce or abolish the symptoms of dumping.48 The use of short-acting octreotide was quite troublesome for patients and only around half saw long-term benefit.49 Encouraging results have been seen with a longer-acting repeatable (LAR) formulation of octreotide, which only needs administration once a month, rather than with each meal.50

An algorithm for the treatment of postoperative dumping is shown in Fig. 18.9.51

Surgical treatment

For patients with truncal vagotomy and drainage procedures, taking down the gastrojejunostomy52 should cure or improve dumping in over 80% of patients. Reconstruction of the pylorus produces similar results.53 After gastrectomy, a number of procedures have been advocated for dumping. The simplest and probably the best is to convert the drainage procedure to a 45-cm Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy. The delay in liquid emptying after this procedure is thought to be due to myoelectrical abnormalities within the Roux limb itself, causing a degree of retrograde contraction. The delay in emptying of solids is probably a result of the vagotomy leading to a degree of gastric atony and loss of the antral propulsive force to propel solid food into the small intestine. Reversal of the proximal 10 cm of the jejunal limb to create an antiperistaltic interposition is unnecessary and may lead to further stasis and dilatation of the interposed segment. This will worsen any symptoms of gastric retention. The interposition of a segment of upper jejunum between the gastric remnant and the duodenum has been advocated. Both isoperistaltic and antiperistaltic interpositions have been used, but these procedures can be associated with serious complications, and the long-term success rate is variable.54

Diarrhoea

Alteration in bowel habit occurs in the majority of patients who undergo truncal vagotomy and in most this is a change from constipation to a more regular habit with one or two motions per day. However, 11% of patients following truncal vagotomy and pyloroplasty had continuous diarrhoea that significantly interfered with their lifestyle.55 A further 20% of patients will have episodic attacks of diarrhoea more than once a week.

Surgical treatment

Closure of a gastrojejunostomy will improve or cure diarrhoea in 80% of patients. A similar improvement is seen with reconstruction of the pylorus. Various intestinal interpositions to act as an intestinal brake have been advocated. The use of a 10-cm antiperistaltic jejunal segment placed 100 cm distal to the duodenojejunal junction has been described. The reversed segment produces a delay in the passage of contents through the small bowel. Many report poor results with these types of operation. The operation that has proved effective is the reverse distal ileal onlay graft, which creates a passive non-propulsive segment.56

Small stomach syndrome

This only occurs after a high subtotal gastrectomy in which 80–90% of the stomach is removed and is very unusual. Typically this leads to epigastric and retrosternal discomfort after ingesting food due to rapid gastric distention and is often accompanied by nausea, hiccoughing, increased flatulence and early satiety. Non-operative treatment consists of frequent small meals, antispasmodics, and mineral and vitamin replacement. Patients may also require fine-bore nasoenteric nutritional supplementation. In a small number of patients with uncontrollable symptoms, surgery may have to be considered. The reservoir jejunal interposition described by Cuschieri, a modification of the Hunt–Lawrence, is probably the procedure of choice.54 Long-term follow-up of these patients is required as there is a tendency for the jejunal limb to elongate over several years and this can lead to stasis and ulceration.

References

1. Mégraud, F., Lehours, P., Helicobacter pylori detection and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(2):280–322. 17428887

2. Eastwood, G.L., Is smoking still important in the pathogenesis of peptic ulcer disease? J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25(Suppl. 1):S1–S7. 9479620

3. Lu, Y.F., Zhang, X.X., Zhao, G., et al, Gastroduodenal ulcer treated by pylorus and pyloric vagus preserving gastrectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 1999;5(2):156–159. 11819417

4. Park do, J., Lee, H.J., Jung, H.C., et al, Clinical outcome of pylorus-preserving gastrectomy in gastric cancer in comparison with conventional distal gastrectomy with Billroth I anastomosis. World J Surg. 2008;32(6):1029–1036. 18256877

5. Stabile, B.E., Morrow, D.J., Passaro, E., Jr., The gastrinoma triangle: operative implications. Am J Surg. 1984;147(1):25–31. 6691547

6. Ellison, E.H., Wilson, S.D., The Zollinger–Ellison syndrome: re-appraisal and evaluation of 260 registered cases. Ann Surg 1964; 160:512–520. 14206854

7. Zollinger, R.M., Ellison, E.C., O’Darisio, T.M., et al, Thirty years of experience with gastrinoma. World J Surg 1984; 8:427–435. 6148806

8. Wu, P.C., Alexander, H.R., Bartlett, D.L., et al, A prospective analysis of the frequency, location, and curability of ectopic (nonpancreaticoduodenal, nonnodal) gastrinoma. Surgery. 1997;122(6):1176–1182. 9426435

9. Ramage, J.K., Davies, A.H.G., Ardill, J., et al, Guidelines for the management of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine (including carcinoid) tumours. Gut 2005; 54:1–16. 15591495

10. Imamura, M., Komoto, I., Ota, S., Changing treatment strategy for gastrinoma in patients with Zollinger–Ellison syndrome. World J Surg 2006; 30:1–11. 16369713

11. Norton, J.A., Fraker, D.L., Alexander, H.R., et al, Surgery increases survival in patients with gastrinoma. Ann Surg. 2006;244(3):410–419. 16926567

12. Norton, J.A., Intraoperative methods to stage and localize pancreatic and duodenal tumors. Ann Oncol. 1999;10(Suppl. 4):182–184. 10436817

13. Møller, M.H., Adamsen, S., Thomsen, R.W., Peptic Ulcer Perforation (PULP) trial group, Multicentre trial of a perioperative protocol to reduce mortality in patients with peptic ulcer perforation on behalf of the. Br J Surg 2011; 98:802–810. 21442610 This study describes a multimodality multidisciplinary perioperative protocol for resuscitation and treatment of sepsis in patients with perforated duodenal ulcers. It suggests a significant reduction in mortality. Although this study has demonstrated impressive results, it is not a controlled study and relies on reference to historical outcomes. It also adopts several measures at once, including the principles of the surviving sepsis campaign and goal-directed therapy, making it difficult to distil the precise interventions that made a difference. The authors themselves acknowledge that their study design inherently places a spotlight on this group of patients and it is impossible to know whether it was simply the increased ‘attention’ to this group rather than any particular element of the protocol that was responsible for the outcome.

14. Taylor, H., Aspiration treatment of perforated ulcers. Lancet 1951; 1:7–12. 14795749

15. Gul, Y.A., Shine, M.F., Lennon, F., Non-operative management of perforated duodenal ulcer. Irish J Med Sci. 1999;168(4):254–256. 10624365

16. Crofts, T.J., Park, K.G.M., Steele, R.J.C., et al, A randomised trial of nonoperative treatment for perforated peptic ulcer. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(15):970–973. 2927479

17. Donovan, A.J., Berne, T.V., Donovan, J.A., Perforated duodenal ulcer: an alternative therapeutic plan. Arch Surg. 1998;133(11):1166–1171. 9820345

18. Mihmanli, M., Isgor, A., Kabukcuoglu, F., et al, The effect of Hpylori in perforation of duodenal ulcer. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45(23):1610–1612. 9840115

19. Ng, E.K.W., Lam, Y.H., Sung, J.J.Y., et al, Eradication of HP prevents recurrence of ulcer after simple closure of duodenal ulcer perforation: randomised controlled trial. Ann Surg 2000; 231:153–158. 10674604

20. Herrod, P.J., Kamali, D., Pillai, S.C., Triple-ostomy: management of perforations to the second part of the duodenum in patients unfit for definitive surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2011;93(7):e122–e124. 22004618

21. Mouret, P., Francois, Y., Vagnal, J., et al, Laparoscopic treatment of perforated peptic ulcer. Br J Surg 1990; 77:1006. 2145052

22. Sommer, T., Elbroend, H., Friis-Andersen, H., Laparoscopic repair of perforated ulcer in Western Denmark – a retrospective study. Scand J Surg 2010; 99:119–121. 21044926

23. Critchley, A.C., Phillips, A.W., Bawa, S.M., et al, Management of perforated peptic ulcer in a district general hospital. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2011;93(8):615–619. 22041238

24. Bertleff, M.J., Lange, J.F., Laparoscopic correction of perforated peptic ulcer: first choice? A review of literature. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(6):1231–1239. 20033725 This paper analysed the results of 36 studies of various designs involving 2788 patients. It found a conversion rate of 12.4%. The laparoscopic approach was associated with less postoperative pain, lower morbidity, less mortality and shorter hospital stay. By contrast, the open group had significantly shorter operation times and lower rate of recurrent leakage.

25. Sanabria, A., Villegas, M.I., Morales Uribe, C.H. Laparoscopic repair for perforated peptic ulcer disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2005. [CD004778]. This Cochrane review, updated in 2010, concluded that the data available at that time (just three randomised trials of acceptable quality) do not support laparoscopic over open surgery. Although there was a trend towards decrease in septic complications, wound infection, ileus, deep vein thrombosis and mortality in favour of the laparoscopic approach, there was a trend in favour of open surgery with respect to intra-abdminal abscess formation and re-operation.

26. Lunevicius, R., Morkevicius, M., Systematic review comparing laparoscopic and open repair for perforated peptic ulcer. Br J Surg. 2005;92(10):1195–1207. 16175515 This systematic review of 25 studies identified shock, delayed presentation (> 24 hours), confounding medical condition, age > 70 years, poor laparoscopic expertise and ASA Grade III–IV as risk factors for conversion to open surgery and postoperative morbidity.

27. Sreedharan, A., Martin, J., Leontiadis, G.I., et al. Proton pump inhibitor treatment initiated prior to endoscopic diagnosis in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (7):2010. [CD005415]. This paper examines the evidence for giving PPIs before endoscopy in cases of upper GI bleeding. Looking at six randomised controlled trials involving 2223 patients there was no difference in outcome but the studies themselves were weak. The authors recommend a pragmatic approach to using PPIs before endoscopy, particularly if endoscopy is likely to be delayed. One of the problems with this type of study is that the patient population studied is, by definition, a heterogeneous group and, while one might intuitively expect a similar response to that seen in post-endoscopy use of PPIs in a high-risk subgroup,27 studies have perhaps not been powered to identify such an effect.

28. Lau, J.Y.W., Sung, J.J.Y., Lee, K.K.C., et al, Effect of intravenous omeprazole on recurrent bleeding after endoscopic treatment of bleeding peptic ulcers. N Engl J Med 2000; 343:310–316. 10922420 This study is a double blind randomised design and, unlike previous reports, included only patients at high risk of re-bleed. It found a reduction in rate of re-bleeding if intravenous omeprazole was given after endoscopy and endoscopic treatment. Previous studies that had not excluded cases at low risk of re-bleed (the great majority), probably for statistical reasons, failed to demonstrate an effect.

29. Leontiadis, G.I., Sreedharan, A., Dorward, S., et al, Systematic reviews of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors in acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11(51):iii–iiv 1–164. 18021578

30. Gluud, L.L., Klingenberg, S.L., Langholz, E., Tranexamic acid for upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(1) CD006640. 22258969 This review looked at seven randomised double blind trials of tranexamic acid in cases of acute upper GI bleeding. The trials did not really reflect modern clinical practice, with studies published from 1973 and the most recent in 2001. They variously use tranexamic acid with placebo and acid antisecretories. No significant differences were found between tranexamic acid and placebo on bleeding, surgery or transfusion requirements, nor between tranexamic acid compared with cimetidine or lansoprazole.

31. Cook, D.J., Guyatt, G.H., Salena, B.J., et al, Endoscopic therapy for acute non-variceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 1992; 102:139–148. 1530782 This paper studied 30 randomised controlled trials evaluating haemostatic endoscopic treatments. Endoscopic therapy significantly reduced rates of re-bleeding, need for surgery and mortality in patients with high-risk endoscopic features of active bleeding or non-bleeding visible vessels. Re-bleeding was rare in patients with ulcers containing flat pigmented spots or adherent clots regardless of endoscopic treatment.

32. Palmer, K., Nairn, M., Guideline Development Group, Management of acute gastrointestinal blood loss: summary of SIGN guidelines. Br Med J 2008; 337:a1832. 18849311

33. Vergara, M., Calvet, X., Gisbert, J.P., Epinephrine injection versus epinephrine injection and a second endoscopic method in high risk bleeding ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2) CD005584. 17443601 This meta-analysis looked at 18 randomised prospective studies involving 1868 patients. It found reductions in re-bleeding (18.5% vs. 10%), need for emergency surgery (10.8% vs. 6.7%) and mortality (4.7% vs. 2.5%) if more than one endoscopic method was used to secure haemostasis at the initial endoscopy.

34. Lau, J.Y.W., Sung, J.J.Y., Lam, Y.H., et al, Endoscopic re-treatment compared with surgery in patients with recurrent bleeding after initial endoscopic control of bleeding ulcers. N Engl J Med 1999; 340:751–756. 10072409 This study from Hong Kong compared the outcome of patients who re-bleed following initial endoscopic haemostasis: 48 were randomised to a further endoscopic treatment and 44 directly to surgery. Although hypotension at randomisation and an ulcer size larger than 2 cm predicted a poor outcome with endoscopic re-treatment, overall a seond attempt at endoscopic treatment proved safe with no increased mortality, fewer complications and spared 73% of cases an operation.

35. Poxon, V.A., Keighley, M.R., Dykes, P.W., et al, Comparison of minimal and conventional surgery in patients with bleeding peptic ulcer: a multicentre trial. Br J Surg. 1991;78(11):1344–1345. 1760699

36. Loffroy, R., Rao, P., Ota, S., et al, Embolization of acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage resistant to endoscopic treatment: results and predictors of recurrent bleeding. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2010; 33:1088–1100. 20232200

37. Ripoll, C., Banares, R., Beceiro, I., et al, Comparison of transcatheter arterial embolization and surgery for treatment of bleeding peptic ulcer after endoscopic treatment failure. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2004; 15:447–450. 15126653

38. Eriksson, L.G., Ljungdahl, M., Sundbom, M., et al, Transcatheter arterial embolization versus surgery in the treatment of upper gastrointestinal bleeding after therapeutic endoscopy failure. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19(10):1413–1418. 18755604

39. Cherian, P.T., Cherian, S., Singh, P., Long-term follow-up of patients with gastric outlet obstruction related to peptic ulcer disease treated with endoscopic balloon dilatation and drug therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66(3):491–497. 17640640

40. Shabbir, J., Durrani, S., Ridgway, P.F., et al, Proton pump inhibition is a feasible primary alternative to surgery and balloon dilatation in adult peptic pyloric stenosis (APS): report of six consecutive cases. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88(2):174–175. 16551413

41. Kim, S.M., Song, J., Oh, S.J., et al, Comparison of laparoscopic truncal vagotomy with gastrojejunostomy and open surgery in peptic pyloric stenosis. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(6):1326–1330. 18813980

42. Koruth, N.M., Krukowski, Z.H., Matheson, N., Pyloric reconstruction. Br J Surg 1985; 72:808–810. 4041713

43. Martin, C.J., Kennedy, T., Reconstruction of the pylorus. World J Surg 1985; 6:221–225. 7090408

44. DeMeester, T.R., Fuchs, K.H., Ball, C.S., et al, Experimental and clinical results with proximal end-to-end duodenojejunostomy for pathological duodenogastric reflux. Ann Surg 1987; 206:414–426. 3662657

45. Strignano, P., Collard, J.M., Michel, J.M., et al, Duodenal switch operation for pathologic transpyloric duodenogastric reflux. Ann Surg. 2007;245(2):247–253. 17245178

46. van der Kleij, F.G., Vecht, J., Lamers, C.B., et al, Diagnostic value of dumping provocation in patients after gastric surgery. Scand J Gastroenterol 1996; 31:1162–1166. 8976007

47. Harju, E., Larmi, T.K.I., Efficacy of guar gum in preventing the dumping syndrome. J Parent Enter Nutr 1983; 7:470–472. 6315982

48. Primrose, J.N., Johnston, D., Somatostatin analogue SMS 201-995 (octreotide) as a possible solution to the dumping syndrome after gastrectomy or vagotomy. Br J Surg 1989; 76:140–144. 2702445

49. Didden, P., Penning, C., Masclee, A.A., Octreotide therapy in dumping syndrome: analysis of long-term results. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24(9):1367–1375. 17059518

50. Arts, J., Caenepeel, P., Bisschops, R., et al, Efficacy of the long-acting repeatable formulation of the somatostatin analogue octreotide in postoperative dumping. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(4):432–437. 19264574

51. Tack, J., Arts, J., Caenepeel, P., et al, Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of postoperative dumping syndrome. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6(10):583–590. 19724252

52. McMahon, M.J., Johnston, D., Hill, G.T., et al, Treatment of severe side effects after vagotomy and gastroenterostomy by closure of gastroenterostomy without pyloroplasty. Br Med J 1978; 1:7–8. 620169

53. Cheadle, W.G., Baker, P.R., Cuschieri, A., Pyloric reconstruction for severe vasomotor dumping after vagotomy and pyloroplasty. Ann Surg 1985; 202:568–572. 4051605

54. Cuschieri, A., Long term evaluation of a reservoir jejunal interposition with an isoperistaltic conduit in the management of patients with a small stomach syndrome. Br J Surg 1982; 69:386–388. 7104606

55. Cuschieri, A., Isoperistaltic and antiperistaltic jejunal interposition for the dumping syndrome. A comparative study. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1977; 22:319–342. 915852

56. Cuschieri, A., Surgical management of severe intractable postvagotomy diarrhoea. Br J Surg 1986; 73:981–984. 3790963