Chapter 36 Benign tumours, cysts and malformations of the genital tract

MALFORMATIONS OF THE GENITAL TRACT

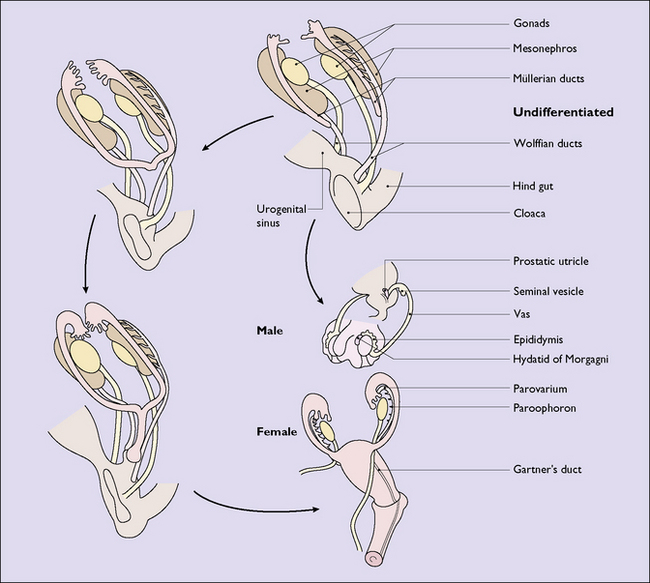

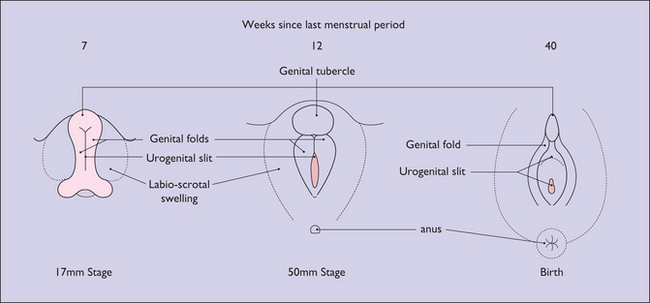

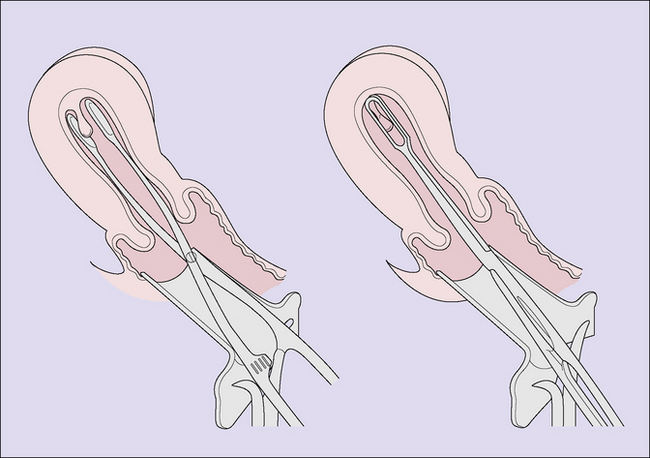

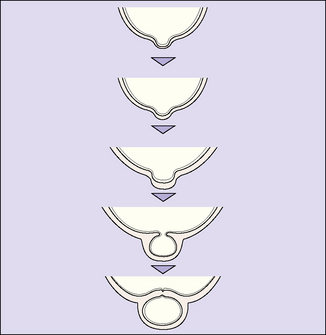

In a female fetus the Müllerian ducts develop from the paramesonephric ducts, growing caudally on each side. By the 35th day after fertilization the lower part of the ducts change direction and grow towards the midline, where they meet and fuse with each other and then grow caudally once again. By the 65th day they have completed the fusion and their medial walls have gradually disappeared to form a single hollow tube (Fig. 36.1). The most caudal portion, which will become the vagina, becomes solid and fuses with an ingrowth of endodermal cells from the cloaca. By the 20th gestational week, the solid growth has recanalized and the external genitalia have formed (Fig. 36.2).

Failure of recanalization

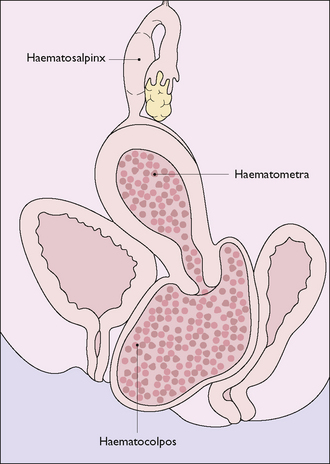

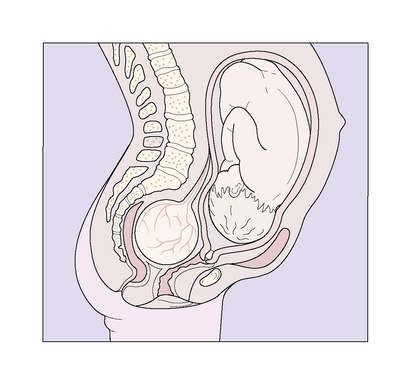

The most common defect is an imperforate hymen or transverse septum, which should be detectable during the examination of the neonate. If it is not detected until after puberty, menstrual discharge may collect in the vagina and, in long-term cases, may distend the uterus and tubes (Fig. 36.3). Treatment is to make a cruciate incision in the hymen septum and permit the inspissated fluid to escape slowly. Less common defects produce complete or partial vaginal atresia.

Failure of the ducts to form or to fuse

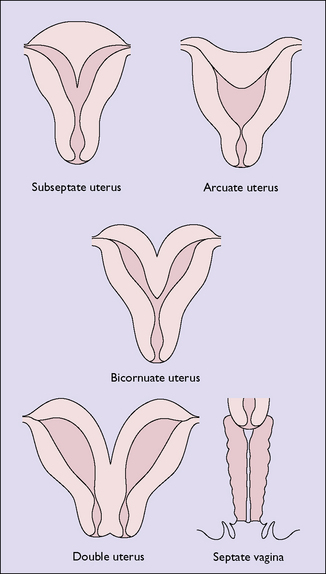

Failure of the two Müllerian ducts to fuse leads to one of several malformations (Fig. 36.4). Most of these malformations do not reduce the woman’s fertility, but should pregnancy occur there is an increased risk of late miscarriage and premature labour. A subseptate uterus may lead to recurrent abortion, and can be treated by excising the septum by surgery or laser. If the woman has a bicornuate uterus and becomes pregnant, the fetus may present as a transverse lie in late pregnancy.

UTERINE TUMOURS

Endometrial polyps

Endometrial polyps may occur in association with endometrial hyperplasia and may be a cause of abnormal uterine bleeding. They are detected by curettage, provided a polyp forceps is also introduced into the uterus (Fig. 36.5), or by hysteroscopy.

Uterine fibroids (leiomyomata, fibromyomas)

These are the most common tumours of the genital tract. A uterine fibroid is composed of smooth muscle bundles interspersed with strands of connective tissue, surrounded by a thin capsule (Box 36.1). The tumour may arise in any part of the Müllerian duct, but occurs most often in the myometrium, where several may develop simultaneously. The tumour may vary from the size of a pea to that of a football.

Box 36.1 Fibroids

| What are they? | Encapsulated smooth muscle fibres interspersed with strands of connective tissue usually developing in the myometrium. They may remain intramural or grow outwards or into the uterine cavity. Dependent on an intact blood supply |

| Aetiology | Unclear |

| Prevalence | Increases from 5% to 20% of women during their reproductive years. More common in nulliparous women and those of low parity. Very slow growing in response to oestrogen. Regress after menopause |

| Diagnosis | Examination and confirmatory ultrasound |

| Symptoms | Depend on size and position and are frequently symptomless. Two most common symptoms are abnormal vaginal bleeding, usually heavy and/or prolonged, and pelvic discomfort, crampy or pressure |

| Management | Depends on rate of growth, size, symptoms and desire for pregnancy |

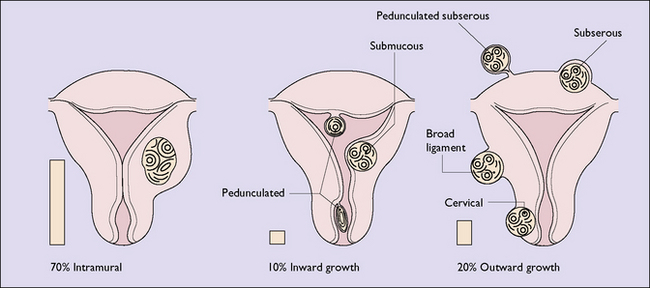

Their aetiology is unclear. They may arise from normal muscle cells, from immature muscle cells in the myometrium, or from embryonal cells in the walls of uterine blood vessels. Whatever their origin, the tumours begin as tiny multiple seedlings which are scattered through the myometrium. The seedlings grow very slowly but progressively (over years rather than months), under the influence of circulating oestrogens, and, unless detected and treated, as most are today, may form a tumour weighing 10 kg or more. At first the tumour is intramural, but as it grows it may develop in several directions. This is shown in Figure 36.6. After the menopause, as oestrogen is no longer secreted in any great quantity, fibroids tend to atrophy.

Pathology

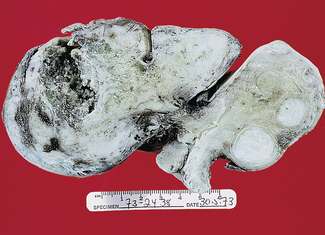

If the tumour is cut, it pouts above the surrounding myometrium as its capsule contracts. Whitish-grey in colour, it is composed of whorled intertwining bundles of muscles in a matrix of connective tissue (Fig. 36.7). At its periphery the muscle fibres are arranged in concentric layers, and the normal muscle fibres surrounding the tumour are similarly oriented. Between the tumour and the normal myometrium a thin layer of areolar tissue forms a pseudocapsule, through which the blood vessels enter the fibroid.

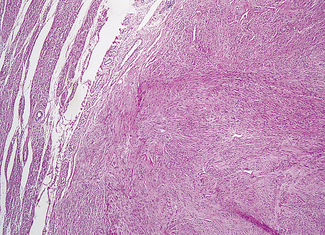

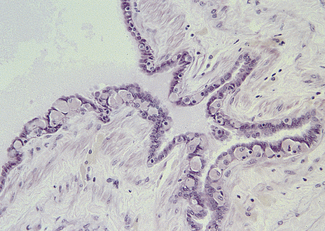

On microscopy, groups of spindle-shaped muscle cells, with elongated nuclei, are separated into bundles by connective tissue (Fig. 36.8). As the entire blood supply of the fibroid is derived from the few vessels entering from the pseudocapsule, the growth of the tumour means that it often outstrips its blood supply. This leads to degeneration, particularly in the central portion of the fibroid. Initially, hyaline degeneration occurs, which may become cystic, or calcification may occur over time – the ‘womb stones’ of 19th-century gynaecologists. In pregnancy, a rare complication (red degeneration) may occur. This follows extravasation of blood through the tumour, giving it a raw beef appearance. In less than 0.1% of tumours sarcomatous change occurs.

Symptomatology

The symptoms depend on the size and the position of the fibroid. Most small fibroids, and some larger ones, are symptomless and are only detected during a routine examination. If the fibroid is submucous, it may be associated with menorrhagia (Fig. 36.9). This may result from an increase of the endometrial surface, increasing uterine vascularity and blood flow, and changes in the ability of the uterus to contract.

Management

Observation

Symptomless fibroids smaller than a 14-week pregnancy may be observed. Other types of fibroids:

Myomectomy

If the woman wishes to preserve her reproductive function, myomectomy may be chosen. Depending on the size and position, and the experience of the surgeon either a laparoscopic or an open abdominal approach will be selected. The operation removes all detected fibroids and reconstitutes the uterus. The woman must accept that, if problems arise during myomectomy, the surgeon may have to proceed to hysterectomy. Following myomectomy, 40% of women who have the opportunity to conceive will do so. If the surgeon did not have to open the uterine cavity then the woman can consider a vaginal delivery. In 5% of women the fibroids recur, and a similar number of women continue to have menorrhagia, which necessitates the use of medication (see p. 227), hysteroscopic resection or hysterectomy.

Hysterectomy

Total hysterectomy is the treatment of choice in older women, women who have no wish for a further pregnancy, and those who have menorrhagia or marked pressure symptoms. A patient should not be rushed into making a decision to have a hysterectomy. She should be given time to think and to ask questions about the procedure. The gynaecologist should also make sure that misconceptions about the operation are addressed. This is discussed on page 227.

Fibroids and pregnancy

BENIGN OVARIAN CYSTS AND TUMOURS

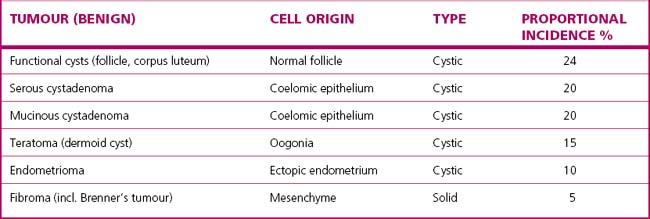

Classification of benign ovarian cysts and tumours

There is no entirely satisfactory classification of ovarian cysts and tumours. This is because of the complexity of ovarian new growths and because the distinction between some of them can only be made after histological examination. Table 36.1 presents a classification and shows the proportions of benign cysts and tumours encountered.

Functional cysts

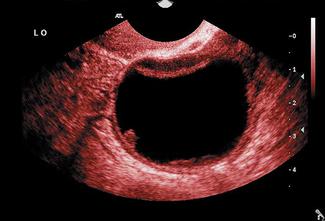

A follicular cyst is an enlargement of an unruptured Graafian follicle that has continued to secrete fluid. The cyst is usually unilateral and less than 5 cm in diameter (Fig. 36.10). The cells may secrete oestrogen or be relatively quiescent, and because of this the symptoms vary. The woman’s menstrual cycle may be lengthened and menorrhagia may occur, or it may be of normal length or shorter.

Corpus luteum cysts occur when, instead of degenerating when the embryo fails to implant, the corpus luteum survives and grows. Theca lutein cysts occur in gestational trophoblastic disease (see p. 143).

Benign ovarian neoplasms

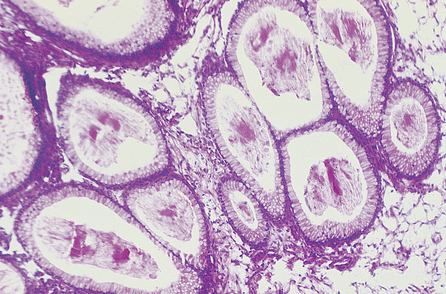

Mucinous cystadenoma

These cysts occur most frequently between the ages of 35 and 55. They can grow to a considerable size and are multilocular (Fig. 36.11). They are usually unilateral and rarely become malignant. The cyst is lined with tall columnar cells, each of which has a basal nucleus and cytoplasmic mucin (Fig. 36.12). Mucin is constantly secreted into the cyst, with the result that its wall becomes tense. Often a portion of the wall bulges outwards and a depression may form at the neck of the bulge, which may become occluded, forming a daughter cyst (Fig. 36.13). Occasionally the cyst may rupture, releasing mucinous cells, which may become attached to the peritoneum and omentum, leading to an intraperitoneal accumulation of mucin (pseudomyxoma peritonei).

Serous cystadenoma

These cysts are also more frequently detected in women aged 35–55. They are lined with cuboidal epithelium, resembling that of the oviduct (Fig. 36.14). The cells secrete thin, watery fluid, but the quantity secreted is not great. In consequence, the tension inside the cyst is low and the epithelial cells proliferate to form intracystic papillomata. In some cases the cells penetrate the cyst wall to form external papillary projections. Serous cystadenoma are uni- or multilocular and in 30% of cases are bilateral (Fig. 36.15). They only grow to a moderate size, with malignant changes occurring in one-third of cases, usually when the woman is in her 50s.

Endometriomata

These ovarian tumours (chocolate cysts) are usually associated with other evidence of endometriosis. They rarely become malignant. Endometriosis is discussed in Chapter 35.

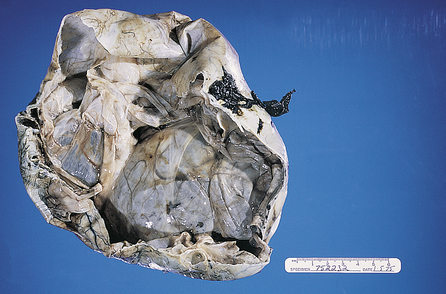

Benign teratoma (dermoid cyst)

Deriving from germ cells, benign teratomata are relatively common. The cyst contains epithelial, mesodermal and endothelial elements. Thus the dermoid may contain hair, teeth and pultaceous material from sebaceous glands. In 10% of cases the tumour is bilateral. It may occur at any age, but mostly is detected when the woman is aged between 20 and 40. The nature of the tumour is confirmed by ultrasound examination or radiology (Fig. 36.16).

Diagnosis of ovarian tumours

Benign ovarian cysts and tumours grow silently and are often undetected for years. They do not cause pain, but if large may cause discomfort. They rarely affect menstrual function. Periodic abdominal and vaginal examinations will detect benign tumours. A painless cystic or solid mass in the cul-de-sac, or in the position of an ovary, or distending the abdomen, which is cystic to firm on palpation, suggests an ovarian tumour. The diagnosis can be confirmed by an abdominal or transvaginal ultrasound scan, which differentiates the tumour from pregnancy, obesity, pseudocyesis, a full bladder or cystic degeneration of a fibroid (Figs 36.10, 36.16).