CHAPTER 95 Benign Tumors and Tumor-Like Lesions of the Oral Cavity

Congenital Conditions

Torus

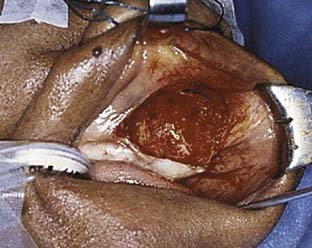

Torus palatinus and torus mandibularis represent developmental anomalies that usually present in the second decade of life and continue to grow slowly throughout life.1 Tori present as mucosally covered bony outgrowths of the palate and mandible. Tori of the oral cavity occur in 3% to 56% of adults and are more common in women.2,3 The tori of the palate are found only in the midline of the hard palate, whereas mandibular tori are found to involve only the lingual surface of the anterior mandible, primarily in the premolar region.1,4 Tori are typically pedunculated or multilobulated, broadly based, smooth, bony masses (Fig. 95-1). They consist of dense lamellar bone with relatively small marrow spaces that do not involve the deeper cancellous bones of the mandible or palate. Patients with tori are usually asymptomatic, unless the torus interferes with denture placement or is repeatedly traumatized when the patient eats. In symptomatic patients, the tori can be treated by removing them from the underlying cortex with osteotomes or cutting burs. Recurrence is occasionally seen; however, malignant transformation has not been reported.

Lingual Thyroid

Approximately 90% of all ectopic thyroid tissue is associated with the dorsum of the tongue.5 Presence of the lingual thyroid reflects the lack of descent of thyroid tissue during development. The lingual thyroid is found in the midline in the area of foramen cecum. The true incidence of lingual thyroid may never be known because this entity does not always result in clinical manifestations; however, studies involving neonatal screening for hypothyroidism revealed that approximately 1/18,000 to 1/100,000 live births were associated with ectopic thyroid tissue involving the tongue.6,7 Although usually asymptomatic, the presence of lingual thyroid can be associated with hypothyroidism. Studies have shown that up to 70% of patients with a lingual thyroid also have hypothyroidism.8 Other symptoms might also be related to the mass effect of the lingual thyroid and might cause airway obstruction and/or difficulties with swallowing. Patients may complain of dysphagia or the sensation of a lump in their throat. Less common complaints include dysphonia or bleeding. Symptoms may occur at times of increased metabolic demands such as growth spurts during adolescence or during pregnancy.9 Malignant transformation is rare.10 Treatment for hypothyroid patients involves thyroid replacement therapy, which may also reduce the size of the lingual thyroid and, in turn, reduce any obstructive symptoms. Treatment for symptomatic euthyroid patients typically involves surgical excision. A number of different approaches for surgical excision of lingual thyroid have been described and include transcervical routes by means of lateral pharyngotomy or transhyoid pharyngotomy, as well as transoral excision with use of the CO2 laser.11 One must be prepared to administer postoperative exogenous thyroid hormone replacement therapy because approximately 70% of patients will have the lingual thyroid as the only functioning thyroid tissue.8

Developmental Cysts

Congenital cystic conditions of the oral cavity and oropharynx are relatively rare. These usually include dermoid cyst, duplication cysts, and nasoalveolar cysts. Dermoid cysts are cystic masses found along embryonic fusion lines and form from epithelial rests.12 Histologically, dermoid cysts are lined by squamous epithelium of the keratinizing variety. They contain elements of epidermal appendages including hair follicles, sweat glands, and connective tissue. Approximately 7% of dermoid cysts are found in the head and neck. Of these, 6.5% to 23% are found in the floor of the mouth.13 Enteric duplication cysts are considered choristomas that contain elements of gastrointestinal mucosa.14 The cysts are lined with stratified squamous and columnar epithelium. They are found anywhere along the digestive tract including the tongue and floor of the mouth. In the oral cavity, duplication cysts present at birth as an asymptomatic swelling involving the tongue and/or the floor of mouth (Fig. 95-2). As dermoid cysts and duplication cysts of the oral cavity enlarge, functional problems such as difficulties with deglutition, speech, and respiration can be expected to occur. Treatment for both dermoid cysts and duplication cysts requires complete excision of the cyst to include all epithelial components.

Nasoalveolar cysts are thought to originate from trapped nasal epithelium between the developing lateral and medial maxillary nasal processes. The manifestations of nasoalveolar cysts usually occur in adulthood as the cyst increases in size.15 Patients typically present with swelling in the nasolabial area, which causes unilateral elevation of the nasal ala. Intraorally, a smooth, mucosal, covered mass in the gingival labial sulcus is seen. Remodeling of the anterior maxilla is also seen (Fig. 95-3). Treatment of nasoalveolar cysts involves complete excision, usually by a sublabial approach (Fig. 95-4). Care should be taken to repair any disrupted nasal mucosa such that the risk of postoperative oronasal fistula is diminished.

Inflammatory/Traumatic Conditions

Fibroma

Irritation fibroma is a common tumor-like condition of the oral cavity and oropharynx. It represents an inflammatory and fibrous hyperplastic response to chronic irritation or trauma. This entity should not be confused with true fibromatous neoplastic conditions such as fibrous histiocytoma, which is uncommon in the oral cavity and oropharynx. It is found in 1.2% of adults and has a 66% female predilection.16 Although this condition can occur at any age, it usually becomes apparent during or after the fourth decade of life. The fibromas are usually solitary and seldom are larger than 1.5 cm. They characteristically present as an asymptomatic, sessile or pedunculated, firm mass involving typically the buccal mucosa and less commonly the labial, or tongue mucosa (Fig. 95-5). Histologically, fibromas are composed of dense and minimally cellular fascicles of collagen fibers and have a relatively avascular appearance. Treatment is with conservative excision, and recurrence is unlikely, unless the precipitating trauma is continued or repeated.

Mucosal Ulcerations

Benign mucosal ulcerations can have the appearance similar to malignant lesions. Numerous local and systemic conditions can manifest themselves, in part, with benign mucosal ulcerations such as recurrent aphthous stomatitis, Crohn’s disease, Behçet’s syndrome, hematinic deficiency, or immunoincompetence. Likely the most common cause for benign ulcerations of the oral cavity and the oropharynx is recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Aphthae represent inflammatory mucosal ulcerations that occur in 20% to 60% of the U.S. population.16 Development of aphthous stomatitis is thought to be related to cell-mediated mechanisms; however, the precise immunopathogenesis is unknown. Stress, local trauma, and/or allergy may play a contributory role in the development of aphthous ulcers. Characteristic features are a painful ulceration surrounded by an erythematous halo with a thin line of coagulation necrosis separating the halo from the saucerized ulcer bed of fibrinoid necrotic debris (Fig. 95-6). Immunoincompetent conditions do not produce the surrounding erythematous ring. Most aphthous ulcerations resolve without therapy within 10 days. Further workup for ulcerations that persist beyond 10 to 14 days should include tissue analysis. Further information pertaining to aphthous stomatitis can be found elsewhere in this text.

Pyogenic Granuloma

Pyogenic granulomas of the oral cavity and oropharynx can occur on any mucosal surface subject to acute or chronic trauma or infection.17 Variants also arise in association with special events such as pregnancy or recent tooth extraction, resulting in epulis gravidarum and epulis granulomatosa, respectively. Most pyogenic granulomas involve the gingiva; however, other common sites include the labial mucosa, the buccal mucosa, and the tongue (Fig. 95-7). They typically present as raised or pedunculated lesions that remain less than 2.5 cm in size. They may bleed with minor trauma. Histologically, pyogenic granulomas consist of a rich profusion of anastomosing vascular channels in an edematous inflammatory and fibrosis stromal background. Lesions usually persist indefinitely, except for those associated with pregnancy. Treatment is by excision and removal of potential traumatic or infective factors.

Necrotizing Sialometaplasia

Necrotizing sialometaplasia is a self-healing, ulcerative, inflammatory reaction of unknown etiology. It has been postulated that it may be precipitated by local trauma that results in vascular compromise.18 This entity typically arises from minor salivary glands and in 77% of cases involves the palate.18 Most cases present with a painful ulceration and surrounding area of swelling that clinically stimulates a malignancy such as squamous cell carcinoma or mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Lesions are typically less than 2 cm. Histologic analysis is required to make the appropriate diagnosis. Light microscopy reveals lobar necrosis and sialadenitis mixed with squamous metaplasia of excretory ducts and acini. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia is usually seen in the associated surface epithelium, which may, due to sampling error, result in a pathologist reporting squamous cell carcinoma. Once definitively diagnosed, treatment is with supportive care because these lesions are self-limiting. Healing takes place within 3 to 6 weeks. Close follow-up during the healing process is necessary because necrotizing sialometaplasia can be found in conjunction with a malignancy.

Amyloidosis

Amyloidosis is a disorder that involves abnormal deposition of extracellular fibril proteins into tissues. Twenty-three different proteins have been identified in amyloidosis with each protein related to a particular clinical setting such as dialysis-associated amyloidosis (β2-microglobulin), plasma cell disorders, (immunoglobulin light chains), or familial amyloidosis (transthyretin). The most common head and neck manifestation of amyloidosis is macroglossia (Fig. 95-8). Amyloid deposition can be such that the function of the tongue becomes limited, resulting in difficulties with speech and swallowing. The diagnosis is made by biopsy, which classically reveals intense green fluorescence also known as apple green birefringence with use of polarized light after Congo red staining. Treatment includes addressing the underlying cause of amyloid deposition if possible, as well as local excision in the case of macroglossia to include tongue reduction. Recurrences can be treated with further conservative resection.

Benign Neoplasms

Papilloma

Various unique squamous-derived entities of the oral cavity and oropharynx exist; however, one of the most frequently occurring conditions is squamous papilloma.19 Approximately 4 out of 1000 adults in the United States have this condition of the oral cavity or oropharynx.16 Squamous papillomas are most commonly associated with HPV-6 and HPV-11 virus subtypes.19 Lesions typically present in adults and generally have a lower recurrence rate, are singular, and are less proliferative than squamous papillomas of other sites of the head and neck such as the larynx.20 Development of precancerous proliferative verrucous leukoplakia within squamous papillomas is rare. Sites of occurrence typically involve the lingual, buccal, and labial mucosa, as well as the tongue (Fig. 95-9). Squamous papillomas typically present as a single, asymptomatic, soft, pedunculated mass with numerous finger-like projections at the surface. Histologically, the projections have fibrovascular cores and demonstrate a relatively narrow base. Treatment involves surgical excision or ablation with use of a CO2 laser. Recurrence in the oral cavity or oropharynx is unlikely.

Granular Cell Tumor

Granular cell tumors are commonly thought to be neural in origin. Granular cell tumors are usually diagnosed during or after the third decade of life. Although this entity can be found throughout the body, more than half of all cases occur in the oral cavity. Greater than a third of granular cell tumors involve the dorsum of the tongue. Other sites of occurrence include the soft palate, uvula, and labial mucosa.16 Up to 15% of patients will have synchronous lesions. Granular cell tumors typically present as firm, painless, relatively immobile, sessile, nodular-appearing lesions less than 1.5 cm in greatest dimension (Fig. 95-10). Histologically, granular cell tumors show large polygonal, oval, or bipolar cells with abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm. Cells often appear in a ribbon pattern and extend to the surface epithelium and demonstrate pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. The malignant variety of granular cell tumors represents approximately 1% of all cases. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice. Recurrence is less than 10%, even with a microscopically positive margin. Congenital epulis is the neonatal form of granular cell tumors. The congenital epulis is evident at birth and characteristically involves the maxillary gingiva (Fig. 95-11). Typically these unifocal growths measure no more than 2 cm, but they may interfere with feeding. Similar to the adult variant, treatment involves surgical excision, which can usually be performed at the bedside. Recurrence is rare.

Neurofibroma

Neurofibroma is the most common of the peripheral nerve neoplasms. The lesion is derived from a mixture of Schwann cells and perineural fibroblasts. Neurofibroma of the oral cavity and oropharynx is typically diagnosed in adolescents and young adults. The finding of multiple neurofibromas may be associated with von Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis (NF1). Approximately 70% of all cases of von Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis involve the oral cavity, primarily the tongue. Solitary neurofibromas of the oral cavity usually involve the tongue, buccal, or labial mucosa16 and present as soft, painless, slow-growing masses, but tender to pressure or palpation. Treatment ideally involves complete surgical excision. Solitary neurofibroma can be excised with relatively little risk of recurrence. Solitary neurofibromas rarely undergo malignant transformation into sarcoma; however, up to 15% of those with von Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis develop a malignancy.

Hemangioma

Hemangioma of the head and neck is relatively common. Hemangioma of the oral cavity represents 14% of all hemangiomas.16 Although usually present at birth with a rapid proliferative phase, they may become clinically evident later in life. They may be associated with a number of conditions including Sturge-Weber-Dimitri syndrome and von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. The lip is the most frequent site of hemangioma involving the oral cavity.16 A mucosal hemangioma will present as a soft, painless mass that is red or blue. Hemangiomas are typically less than 2 cm in greatest dimension; however, they can become quite extensive to involve significant portions of the oral cavity and oropharynx to include the tongue. Hemangiomas tend to spontaneously regress over the years; however, there may be incomplete involution or associated fibrosis.21 Hemangiomas that limit the form and function of the oral cavity and oropharynx are usually treated with conservative surgical excision. Recurrence or persistence is not unusual. Intralesional sclerosing agents, interferons, laser treatment, local and systemic steroids, and radiation have been reported as primary or adjunctive treatment with varying success.21,22

Ameloblastoma

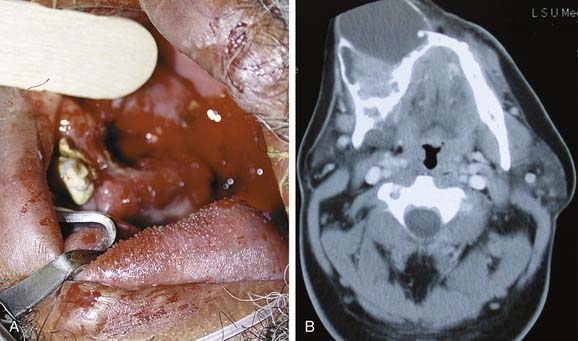

Conditions of odontogenic origin can present as tumors or tumor-like conditions of the oral cavity. Ameloblastoma is the most common neoplasm of odontogenic origin. Ameloblastomas are thought to arise from rests of primitive dental lamina related to the enamel organ in alveolar bone. Patients are typically seen in the third decade of life with a painless mass involving the maxilla or mandible (Fig. 95-12A). In approximately 85% of cases, the mandible is involved, usually at the molar/ramus area.23 Plain radiographic imaging usually reveals a unilocular or multilocular radiolucency. Cortical bone expansion can be seen (see Fig. 95-12B). Histologically, ameloblastomas are solid infiltrating tumors with a follicular or plexiform pattern, which exhibit an element of cystic change. Treatment for ameloblastoma is en bloc resection with at least 1-cm margins of normal-appearing tissue. The overall recurrence rate is 22%, with nearly half of all recurrences occurring within 5 years.24 Lifelong follow-up is recommended. Malignant transformation can occur but is rare. Further information regarding ameloblastoma and odontogenic conditions can be found elsewhere in this text.

Pleomorphic Adenoma

Minor salivary glands are unencapsulated seromucinous glands located immediately beneath the mucosa throughout the oral cavity and oropharynx. Less than 10% of salivary gland tumors arise from minor salivary glands. Approximately 40% of tumors arising from minor salivary glands are benign.25 Pleomorphic adenoma is the most frequently encountered benign tumor of minor salivary glands.26 Other benign minor salivary gland tumors include canalicular adenoma, papillary cystadenoma, oncocytoma, and myoepithelioma. The most commonly occurring site of pleomorphic adenoma in the oral cavity is the hard palate (Fig. 95-13). Other presenting sites include the lip, buccal mucosa, alveolar ridge, floor of mouth, and tongue in decreasing order of frequency. Pleomorphic adenomas of the oral cavity tend to appear smooth and are relatively slow growing.

Bouquot JE, Nikai H. Lesions of the oral cavity. In: Gnepp DR, editor. Diagnostic Surgical Pathology of the Head and Neck. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2001.

Brannon RB, Fowler CB, Hartman KS. Necrotizing sialometaplasia: a clinicopathologic study of sixty-nine cases and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;72:317.

Carlson ER, Marx RE. The ameloblastoma: primary, curative surgical management. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64(3):484-494.

Kerner MM, Wang MB, Angier G, et al. Amyloidosis of the head and neck. A clinicopathologic study of the UCLA experience, 1955-1991. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121(7):778-782.

Winslow CP, Weisberger EC. Lingual thyroid and neoplastic change: a review of the literature and description of a case. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:S100.

1. Rezai RF, Jackson JT, Salamat K. Torus palatinus, an exostosis of unknown etiology: review of the literature. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1985;6:149.

2. Bouquot JE. Common oral lesions found in a large mass screening. J Am Dent Assoc. 1986;112:50.

3. Sonnier KE, Horning GM, Cohen ME. Palatal tubercles, palatal tori, and mandibular tori: prevalence and anatomical features in a U.S. population. J Periodontol. 1999;70:329.

4. Antoniades DZ, Belazi M, Papanayiotou P. Concurrence of torus palatinus with palatal and buccal exostoses: case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;85:552.

5. Williams JD, Sclafani AP, Slupchinskij O, et al. Evaluation and management of the lingual thyroid gland. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1996;105:312.

6. Fisher D, Dussault J, Foley T, et al. Screening for congenital hypothyroidism: results of screening one million North American infants. J Pediatr. 1979;94:700.

7. Kaplan EL. Thyroid and parathyroid. In: Schwartz SI, Shires GT, Spencer FC, editors. Principles of Surgery. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1989:1614.

8. Kansal P, Sakati N, Rifai A, et al. Lingual thyroid: a diagnosis and treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:2046.

9. Taibah K, Ahmed M, Baessa E, et al. An unusual cause of obstructive sleep apnoea presenting during pregnancy. J Laryngol Otol. 1998;112:1189.

10. Winslow CP, Weisberger EC. Lingual thyroid and neoplastic change: a review of the literature and description of a case. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:S100.

11. Puxeddu R, Pelagatti CL, Nicolai P. Lingual thyroid: endoscopic management with CO2 laser. Am J Otolaryngol. 1998;19:136.

12. Quraishi HA, Ortiz O, Wax MK. Dermoid cyst of the floor of the mouth. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;118:562.

13. Bloom D, Carvalho D, Edmonds J, et al. Neonatal dermoid cyst of the floor of the mouth extending to the midline neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:68.

14. Lipsett J, Sparnon AL, Byard RW. Embryogenesis of enterocystomas—enteric duplication cysts of the tongue. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;75:626.

15. Hynes B, Martin L. Nasoalveolar cysts. J Otolaryngol. 1994;23:194.

16. Bouquot JE, Nikai H. Lesions of the oral cavity. In: Gnepp DR, editor. Diagnostic Surgical Pathology of the Head and Neck. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2001:141.

17. Mooney MA, Janniger CK. Pyogenic granuloma. Cutis. 1995;55:133.

18. Brannon RB, Fowler CB, Hartman KS. Necrotizing sialometaplasia: a clinicopathologic study of sixty-nine cases and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;72:317.

19. Ward KA, Napier SS, Winter PC, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus DNA-sequences in oral squamous cell papillomas by the polymerase chain reaction. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1995;80:63.

20. Sakakura A, Yamamoto Y, Takasaki T, et al. Recurrent laryngeal papillomatosis developing into laryngeal carcinoma with human papilloma-virus type-18. Case report, J Laryngol Otol. 1996;110:75.

21. Waner M, Suen JY, Dinehart S. Treatment of hemangiomas of the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:1123.

22. Mulliken JB, Boon LM, Takahashi K, et al. Pharmacologic therapy for endangering hemangiomas. Curr Opin Dermatol. 1995:109-113.

23. Nastri AL, Wiesenfeld D, Radden BG, et al. Maxillary ameloblastoma: a retrospective study of 13 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;33:28.

24. Reichart PA, Philipsen HP, Sonner S. Ameloblastoma: biologic profile of 3677 cases. Oral Oncol Ear J Cancer. 1995;31B:86.

25. Waldron CA, El Mofty S, Gnepp DR. Tumors of the intraoral minor salivary glands: a demographic and histologic study of 426 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;66:323.

26. Batsakis JG. Tumors of the major salivary glands. In: Batsakis JG, editor. Tumors of the Head and Neck: Clinical and Pathological Considerations. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1979:1.