Chapter 17 Benign Strictures

Esophageal Strictures

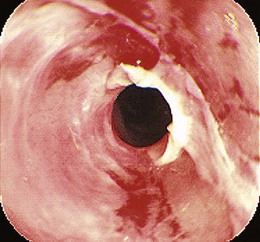

The most common presenting symptom of an esophageal stricture is solid food dysphagia. Although there continues to be some debate about whether a barium esophagogram or upper endoscopy is the best initial test in patients with dysphagia,1 many gastroenterologists favor endoscopy because the diagnoses that benefit from a barium x-ray, such as achalasia and Zenker’s diverticulum, are uncommon, and endoscopy offers both diagnosis and treatment for most patients. Dysphagia can be a symptom of gastrointestinal reflux disease (GERD) without the presence of a stricture.2 Dysphagia typically occurs when the esophagus narrows to a diameter of 13 mm or less (≤39-Fr). Mild degrees of stenosis can be missed endoscopically, and patients with persistent dysphagia after a normal endoscopy and a therapeutic trial of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) should have a barium esophagogram subsequently performed. The most common etiology of benign esophageal stricture is GERD (Fig. 17.1).

Because of the widespread use of PPIs, peptic strictures are becoming less common3 and are recurring less frequently.4 They are usually at their worst at the initial presentation.5 Another etiology of esophageal strictures is corrosive (or caustic) strictures, resulting from either alkali or strong acid ingestion. Compared with peptic strictures, corrosive strictures require more dilation sessions, and the chance of recurrence is higher.6 Radiation-induced, infection-induced,7 pill-induced,8 sclerotherapy-induced,9 and eosinophilic esophagitis–induced esophageal strictures are less common (Table 17.1).10 Extrinsic compression of the esophagus can also cause symptomatic esophageal stenosis. The most common causes of extrinsic esophageal compression are mediastinal tumors, such as breast and lung cancer and lymphoma, although compression by lymph nodes in tuberculosis and histoplasmosis and by vascular structures such as an aberrant right subclavian artery (arteria lusoria)11,12 also occurs.

| Mucosal disease | Gastrointestinal reflux disease (peptic stricture) |

| Caustic injury (corrosive ingestion, sclerotherapy) | |

| Radiation injury | |

| Pill-induced esophagitis | |

| Rings and webs | |

| Infectious esophagitis | |

| Eosinophilic esophagitis | |

| Anastomotic strictures | |

| Motility disorders | Achalasia |

| Scleroderma or CREST syndrome | |

| Hypothyroidism | |

| Other motility disorders | |

| Mediastinal compression | Mediastinal infections (tuberculosis, histoplasmosis) |

| Arteria lusoria |

CREST, calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, scleroderma, and telangiectases.

Dilation of Esophageal Strictures

Most reported series on the treatment of benign esophageal strictures are composed predominately or exclusively of patients with peptic strictures. Consequently, published guidelines on the management of strictures are based primarily on the results of studies of patients with peptic lesions.1,13

There are three primary types of dilator (Table 17.2). The first, and historically most widely used, type comprises the mercury-filled or tungsten-filled rubber bougies, either blunt-tipped (Hurst) or with a tapered tip (Maloney). Except for home dilation performed by patients, weighted bougies have been replaced by wire-guided, tapered, polyvinyl bougies or by balloons in most endoscopy units. The major advantage to the wire-guided bougie is the security of knowing that the tip is directed through the stricture rather than into a side wall. This security is heightened by the use of fluoroscopy for wire-guided bougie dilation, although fluoroscopic guidance is unnecessary unless the stricture is extremely narrow or tortuous. There are several manufacturers of wire-guided bougies. The Celestin dilator has a series of short steps, which increase the diameter in a stepwise manner, rather than a smooth taper. In the United States, the Savary (Wilson-Cook) and American Endoscopy (Bard) bougies are the most popular. They differ in the length of the taper and the method for making them radiopaque. Available diameters range from 5 to 20 mm (15-Fr to 60-Fr).

| Mercury- or tungsten-filled bougies | Maloney (tapered tip) |

| Hurst (blunt tip) | |

| Wire-guided polyvinyl bougies | Savary |

| American Endoscopy | |

| Celestin (stepwise diameter increase) | |

| Balloon dilators | Through the scope (TTS) |

| Controlled radial expansion (CRE) through the scope | |

| Over-a-wire fluoroscopic control |

There is insufficient evidence to support claims that fluoroscopic guidance improves the safety of esophageal dilation.14 In a study of 145 patients treated with Maloney dilators, fluoroscopy was found to alter the dilation technique in 24%.15 Fluoroscopy was found to be particularly useful for ensuring proper dilator passage in patients with large hiatal hernias. However, the wire-guided bougie alleviates the need for fluoroscopic control. Only in very tight, long, or tortuous strictures where the wire does not freely pass through the stricture is fluoroscopy needed. In a study of more than 300 patients using wire-guided bougienage, only 8% of the patients required fluoroscopically guided dilation.16

Controlled radial expansion (CRE) balloons are a more recent development in balloon dilation. Individual dilating balloon catheters have three different stepwise inflation diameters that achieve gradated dilation. An in vitro study showed that CRE balloons deliver a consistently reproducible and progressively greater dilating force.17 The three dilation steps are 1 to 1.5 mm apart for all of the CRE balloon sizes. For example, the 6-mm or 18-Fr balloon achieves 12-Fr size at the first inflation step, 15-Fr size at the second step, and 18-Fr at the final dilation step. The 18-mm balloon has three steps at 16 mm, 17 mm, and 18 mm (48-Fr, 51-Fr, and 54-Fr).

Advantages for TTS balloons are that dilation can be performed immediately during the endoscopy and that the endoscope can be passed through the stricture after dilation. Complete endoscopic examination with biopsy and cytology is facilitated. The major disadvantage of balloons is that they are more expensive, and some are fragile. In bougienage, dilation is accomplished by the radial vector of an axially directed force. In contrast, balloon dilators deliver the entire dilating force radially and simultaneously over the entire length of the stenosis, rather than progressively from the proximal to the distal extent. There is less longitudinal shear stress with balloons.18 For balloons, the radial vector force is that exerted by the circumference of the balloon, and the magnitude of this force is related to the length and curvature of the balloon waist at the onset of dilation. The dilating force is greater if the stricture is tighter and longer.19

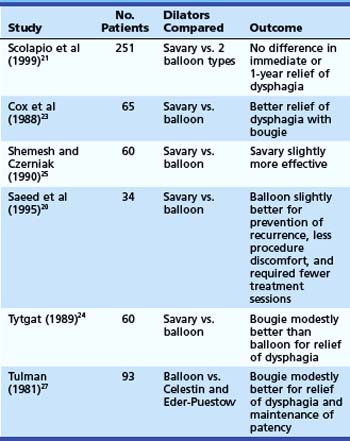

Relatively few patients have been studied in randomized trials comparing the efficacy and safety of the different dilator types.20–27 Of six randomized controlled studies (Table 17.3) comparing wire-guided bougienage with balloon dilation, four concluded that a wire-guided bougie was modestly better than a balloon for reduction of dysphagia; one study found that balloon dilation was modestly better than bougienage for prevention of recurrence, required fewer sessions, and had less procedural discomfort; and one study found no difference with regard to relief of dysphagia or the need for repeat dilation. There seems to be no clear superiority in these various outcome measures for one technique over another. One study comparing the risk of perforation with Maloney dilators, wire-guided bougienage, and balloons concluded that Maloney dilation had a greater risk of perforation than the other two techniques.22 Most endoscopy units have both balloon and wire-guided bougie devices available.

Esophageal Dilation Technique

Patient preparation for esophageal dilation should include holding warfarin or correcting coagulation defects before the procedure. Transient bacteremia is common with endoscopic procedures,28 but routine antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended as per the 2008 American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) guidelines.29

There is no clear consensus on the optimal size to which a peptic stricture should be dilated. Dysphagia seems to occur when the esophagus is narrowed to less than 13 mm (<39-Fr). Most series report dilation to gauge diameters between 40-Fr and 60-Fr with good relief of symptoms and very low complication rates.30,31 Although no study has documented a higher perforation risk with larger dilator sizes, it is generally assumed that little therapeutic benefit exists with dilation greater than 50-Fr to 54-Fr, and the possibility of increased risk exists.

When dilating a stricture with bougies, the initial dilator size chosen should approximately equal the estimated stricture diameter. It has been recommended that the stepwise increase in bougie size should be not more than three sizes above that at which significant resistance is felt—the “rule of threes.” There are no studies to validate that adherence to this rule increases safety of the procedure. Reported series of patients treated by balloon dilation often use balloon diameters that are larger than the “rule of threes.” Also, in a large series of more than 400 patients in which multiple dilators or a single large dilator (>45-Fr) was passed in a single session, only one perforation was observed.32 Given the risks of perforation, however, it is prudent not to try to accomplish too much dilation in a single setting. Patients can be brought back in 1 to 2 weeks, or even shorter intervals of several days, for repeat sessions to achieve an adequate dilation.

Complications of Esophageal Dilation

The major complications of esophageal dilation are perforation and bleeding. Although there is considerable variation in the studies available, the overall serious complication rate seems to be 0.5%, with perforation and bleeding approximately equal in frequency.33,34 It has been suggested that “blind” Maloney dilation has a higher perforation rate than wire-guided bougie.22 However, if wire-guided techniques are reserved for tighter, longer, more difficult strictures, they may show more complications. Perforation usually is obvious with the patient exhibiting distress and in pain. Subcutaneous emphysema may not develop quickly. A chest x-ray and water-soluble x-ray contrast swallow examination should be performed if perforation is suspected. Surgical consultation is mandatory, although many confined perforations have been managed conservatively with no oral intake and intravenous antibiotics. Bleeding severe enough to require transfusions often leads to a repeat endoscopy to determine if endoscopic therapy is required, although most bleeding from esophageal tears stops spontaneously.

Antibiotic Prophylaxis

In 2008, the ASGE published a consensus guideline for antibiotic prophylaxis before endoscopy.29 The recommendations state that routine antibiotic prophylaxis before endoscopic dilation is not indicated regardless of underlying cardiovascular pathology. Although three prospective trials showed the rate of transient bacteremia after esophageal dilation to be 12% to 22%,35–37 activities of daily living are associated with higher rates of bacteremia. Chewing food is associated with a rate of bacteremia of 7% to 51%, and brushing and flossing the teeth are associated with rates of 20% to 40%.38 The guidelines state that transient bacteremia is not a marker of persistent infection or infective endocarditis and that antibiotic prophylaxis before endoscopic dilation is not recommended.29

Stricture Recurrence

Before PPIs were available, approximately 60% of patients required repeat dilations for recurrent dysphagia.39,40 With PPI therapy, 30% of patients with peptic strictures require repeat dilations within 1 year.41 Factors that predict stricture recurrence depend on the type of stricture. One study evaluated 87 outpatients with either peptic or nonpeptic strictures undergoing initial dilation and followed them for 1 year. In multivariate analysis, narrower stricture diameter and nonpeptic strictures were predictors for early recurrence. The significant predictors for peptic stricture recurrence were the presence of a hiatal hernia and the persistence of heartburn after dilation.42 The technique of self-bougienage can be taught to patients who require very frequent esophageal dilation despite intensive medical therapy and for whom surgery is either contraindicated or unacceptable. Published data on self-bougienage are very limited, but it seems to be both safe and effective.43 Given the efficacy of PPIs, self-bougienage for peptic strictures may be primarily of historical interest.

Recalcitrant Esophageal Strictures

Refractory strictures are more commonly due to corrosive injury or surgical anastomoses than a peptic etiology.44–46 Steroid injection has been recommended for refractory benign esophageal strictures.47–53 Using a 22-gauge or 23-gauge sclerotherapy needle, four aliquots of 0.50 mL of triamcinolone acetonide are injected before dilation. The dilution of triamcinolone injectant can range from 10 to 40 mg/mL for a total dose of 40 to 100 mg of triamcinolone injected. Some studies report injecting proximal to the strictured segment in addition to within the strictured segment, whereas others report injecting into the strictured segment alone. Although most studies perform the injection before dilation, some experts believe that injection after dilation, once the stricture has been disrupted, is more effective. A study of 14 patients with corrosive strictures showed a marked decrease in the dilation requirement compared with their own historical control.53

Similar success was reported in a series of 31 patients with strictures resulting from various causes, including 12 patients with peptic etiology and 8 postsurgical anastomotic strictures, radiation therapy–induced strictures, pill-induced strictures, and sclerotherapy-induced strictures. Intralesional steroid injection led to a significant reduction in the number of dilation sessions in all subjects.52 There has been one prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of endoscopic steroid injection for recalcitrant esophageal peptic strictures. In this study of 30 patients, 15 patients received sham therapy followed by TTS balloon dilation and were compared with another 15 patients who received endoscopic steroid injection with subsequent TTS balloon dilation. The groups were identical in pretreatment dysphagia frequency and severity, stricture length and location, use of PPIs, and presence of a hiatal hernia. Although the study was powered to only 60% given the lower than anticipated enrollment, only 2 of 15 patients in the steroid group compared with 9 of 15 patients in the sham group required repeat dilation at 1-year follow-up.47 This prospective randomized controlled trial further supports prior noncontrolled case series advocating the use of steroid injection for recalcitrant strictures.48–53

Removing staples and suture material from the anastomosis using a grasping forceps is thought to reduce stricture recurrence. Another endoscopic treatment that has been reported in the treatment of benign anastomotic esophageal stenosis is the use of electrocautery.54,55 Approximately six radial incisions, each about 2 to 3 mm long, are made using a needle-knife sphincterotome. Hordijk and colleagues55 enrolled 20 patients for treatment with electrocautery who had failed prior dilation therapy for anastomotic esophageal strictures. Of 12 patients with a stricture length of less than 1 cm, all remained symptom-free at 1 year. In eight patients with a stricture length of 1.5 to 5 cm, dysphagia recurred, and a mean of three treatments were necessary. Only two of these eight patients were treatment failures. The use of electrocautery has also been described in combination with balloon dilation56 and argon plasma coagulation.57 At this time, electrocautery should be considered an alternative treatment in short-segment (<1 cm) esophageal, anastomotic ringlike strictures. Whether this modality should be used as a solitary treatment or in conjunction with other modalities has not been determined.58

One novel approach to the treatment of benign, recalcitrant esophageal strictures was the use of endoscissors to cut the stenosed segment. Although this method was reported only as a case report and has not been studied in a randomized trial, endoscissors may be a device to use in refractory cases.59

Surgical treatment of refractory strictures is another alternative. There are two major approaches: (1) antireflux surgery with intraoperative stricture dilation and (2) esophageal reconstruction such as a gastric pull-through or colonic interposition. For peptic strictures that are associated with esophageal shortening, a lengthening procedure such as a Collis gastroplasty may be needed in addition to the antireflux surgery. Comparisons of surgical treatment for peptic strictures by antireflux surgery and intraoperative dilation versus nonsurgical therapy showed similar success rates.60,61 The major advantage to surgery is the decreased need for long-term medical therapy. However, with long-term follow-up, most patients have reinstituted antireflux medications regularly.62 One difficult subset of patients with esophageal peptic stricture comprises patients with esophageal motility disorders such as scleroderma. The abnormal esophageal motor function and mechanical obstruction caused by fundoplication can result in significant postoperative dysphagia, although there are reports of scleroderma patients with excellent surgical outcomes.63 For severe strictures, often not resulting from peptic etiology, surgical resection and reconstruction is required with substantially higher morbidity and mortality.

The use of self-expanding metallic stents (SEMS) for the treatment of refractory benign esophageal strictures has been reported.64 Early success rates are high, although late complications, primarily stricture above the stents, have been reported.65,66 When stents are placed completely within the esophageal lumen, stricture formation also occurs at the distal end of the stent. SEMS generally are contraindicated for the treatment of benign strictures because of difficult long-term complications.

Self-expanding plastic stents (SEPS) have been studied for the treatment of benign esophageal strictures. The only current SEPS that is commercially available is the Polyflex stent, which is a silicone device with an encapsulated monofilament braid made of polyester. An initial positive result with a Polyflex stent for benign esophageal strictures was reported by Repici and colleagues67 in a study in which 12 of 15 patients had long-term relief of dysphagia at follow-up with only 1 patient experiencing stent migration. Several subsequent studies noted, however, that stent migration is common, the patient’s dysphagia regularly returns, and there are serious complications associated with stent placement and removal. A review article by Siersema68 summarized these nine studies (eight retrospective and one prospective) of 162 patients who underwent Polyflex stent placement for benign esophageal strictures. In this review, eight of nine studies showed migration in 60 of 129 patients (47%), and only 50 of 129 patients (39%) had long-term relief of dysphagia. Ten of 129 patients (6%) had major complications: two perforations, two fistulas, three bleeds, and three severe pain requiring stent removal. The last study in this review included a retrospective study by Holm and associates69 at the Mayo Clinic from 2002 to 2006. In this study, 30 patients had 83 of 84 stents placed successfully. Migration occurred in 60% of all procedures, and only 17% of all patients had long-term resolution of symptoms.

Finally, biodegradable stents have been evaluated for the treatment of esophageal strictures. Two types of materials, natural and synthetic, have been tested with biodegradable stents. Natural materials such as catgut collagen and fibrin were shown to be of limited efficacy given the poor mechanical strength and poor conversion to the degradable form of fiber.70 Three studies have been done with a polyactide-made biodegradable stent.71–73 Although one study showed migration in 10 of 13 patients 10 to 21 days after placement, none of these 13 patients had dysphagia at follow-up 7 to 24 months later.73 The results are promising with this synthetic material, but longer term studies with more technologically advanced stents are warranted before considering their use for benign esophageal strictures.

Esophageal Rings and Webs

Episodic and nonprogressive dysphagia without weight loss is characteristic of an esophageal web or a distal esophageal ring (Schatzki ring). The first episode often occurs during a hurried meal or with alcohol. The patient notes that the food is stuck in the distal esophagus and can often be passed by drinking large quantities of liquids. The offending food is frequently a piece of bread or steak and hence the description “steakhouse syndrome.”74

Esophageal Rings

Two types of distal esophageal rings are described: the A and B (Schatzki) rings. The A or muscular ring is the proximal border of the lower esophageal sphincter. It is covered by squamous epithelium and can be shown only very rarely on esophagogram. If it is symptomatic, it can be treated by passage of a 50-Fr bougie or by injection of botulinum toxin.75

In contrast, the B ring, otherwise known as the mucosal or Schatzki ring, is very common and is found in 6% to 14% of subjects undergoing barium GI series.76 It is a thin membrane that has squamous epithelium on its upper surface and columnar epithelium on its lower surface; it demarcates the squamocolumnar junction. The Schatzki ring is composed of mucosa and submucosa, and there is no muscularis propria. It is believed that most Schatzki rings are congenital in origin, although a relationship to GERD has been proposed.77 It is unclear how many are truly scar tissue caused by acid reflux. Most rings shown at upper endoscopy or on barium esophagograms are asymptomatic. When the esophageal lumen is narrowed to less than or equal to 13 mm, rings can cause solid food dysphagia and food impactions.

Rings causing dysphagia are effectively treated by passage of a single large (50-Fr or 54-Fr) bougie or by a series of dilators of progressively larger diameter. Although passage of a single large dilator is the most popular means of therapy, there are no studies to confirm the superiority of this technique over the gradual dilation typically used for peptic strictures. Repeat dilations are required in most patients with Schatzki rings because 90% have recurrent dysphagia within 3 years. However, a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial showed that acid suppressive therapy may prevent the relapse of lower esophageal (Schatzki) rings.78 This trial enrolled 44 patients with symptomatic Schatzki rings. Patients who did not have GERD based on esophageal manometry and 24-hour ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring measurements were randomly assigned to receive 20 mg of daily omeprazole versus placebo. At 19-month follow-up, only 1 of 13 patients (7.7%) treated with 20 mg of omeprazole daily had recurrence of Schatzki ring compared with 7 of 12 (58.3%) patients receiving placebo. An alternative treatment for Schatzki rings is four-quadrant biopsy causing disruption of the ring. In a randomized study comparing this technique with passage of a single 52-Fr Maloney dilator, there was no difference in efficacy or in durability of response with 12-month follow-up.79

Electrocautery incision of Schatzki rings has also been reported.80–82 In one case series study, 11 patients who had failed prior dilation were treated with dilation followed by endoscopic incision. The combination of treatments provided a longer dysphagia-free interval compared with repeated bougienage alone.83 Further support for electrocautery was reported in a randomized, prospective trial, which found that electrosurgical incision provided longer dysphagia-free survival time than bougie dilation for patients with Schatzki rings.84 Study limitations included that patients treated with bougie had higher pretreatment dysphagia scores than patients treated with incision, there were a limited number of patients in each group (n = 25), there was no diet score, and there was a high study dropout rate.85 More randomized controlled trials comparing electrosurgical incision with dilation are needed before accepting incision therapy as superior to dilation alone for patients with Schatzki rings.

Esophageal Webs

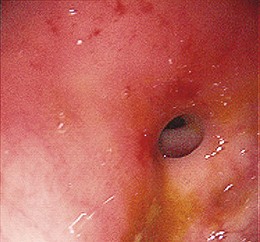

Esophageal webs are one or more thin horizontal membranes of squamous epithelium within the upper and mid esophagus. In contrast to rings, they rarely encircle the lumen but protrude from the anterior wall extending laterally but not posteriorly. Webs may be asymptomatic but do cause solid food dysphagia and can manifest at any age. They are usually fragile membranes that respond well to dilation with bougienage after initial rupture by the endoscope (Fig. 17.2).86 An association between cervical webs and iron deficiency anemia in adults (especially women) has been described as the Plummer-Vinson syndrome or Paterson-Kelly syndrome. This condition has also been associated with celiac sprue. The pathogenesis of this syndrome is unclear.

Eosinophilic Esophagitis

Eosinophilic esophagitis, also referred to as small-caliber esophagus, has been documented with increasing frequency over the last decade.87–89 It is commonly seen in young patients who present with dysphagia or food impaction or both, but it can also mimic symptoms of reflux disease alone.90,91 After treating the patient with a trial of a PPI, diagnosis requires endoscopic biopsies of the proximal and distal esophagus that show greater than 15 to 20 eosinophils per high-power field. Proximal esophageal biopsies are done to confirm the presence of eosinophils because distal esophageal eosinophils can also be seen with reflux alone.92 Endoscopically, the esophagus may be normal in appearance or show ridges, furrows, or rings. The appearance of this ringed esophagus can be described as a “feline esophagus” because cats have similar-appearing esophageal rings. Other synonyms for a ringed esophagus include “corrugated esophagus” or “trachealization of the esophagus.”93 Although dilation may lessen dysphagia, there is an increased risk of mucosal tearing and perforation with dilation for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, so dilation should be performed with caution.93,94 Additional treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis includes swallowed fluticasone for a finite duration, consideration of referral to an allergist, avoidance of documented allergens, and a PPI.

Gastric, Pyloric, and Small Bowel Strictures

The major question for patients with nonesophageal strictures is the appropriateness of balloon dilation versus surgical therapy. This decision depends on the etiology of the stenosis and the long-term outcome for dilation therapy. When dilation therapy is chosen, most nonesophageal stenoses are best treated with balloon dilation. These can be placed over an endoscopically or radiographically placed wire or passed through the endoscope. Balloons passed through the endoscope (TTS or CRE) have the advantage of allowing completion of the endoscopic examination after dilation and are the most popular. Similar to esophageal balloons, CRE balloons allow three-step dilation with a single balloon, although the steps are only 1 mm apart, and the balloons are significantly more expensive than single-sized TTS balloons. Pyloric (and colonic) balloons are shorter in length than esophageal balloons with usual lengths of 3 to 4 cm. Some experts recommend the use of fluoroscopy and 10% to 25% contrast solution with endoscopic balloons to assess the bulb apex or C-loop wall better during inflation.95 Technical variables such as the duration of balloon insufflation, the frequency and adequacy of dilation, and the size of balloons used have not been standardized. The successful use of Savary-Gilliard dilators for obstruction of the distal stomach and duodenal bulb has also been described in case reports.96

Causes of Nonesophageal Upper Gastrointestinal Tract Strictures

The most common site for nonesophageal, upper GI tract strictures is at the pylorus, although gastric, anastomotic, and duodenal strictures also occur. Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is the most common cause of gastric outlet obstruction. PUD occurs most often due to a history of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use, whereas Helicobacter pylori infection infrequently causes PUD.97 The initial technical failure rate of pyloric dilation, or an “intention-to-treat” analysis, is not reported in most case series. One report of 46 consecutive patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction had initial technical failure in 5 patients (11%).98 A second series reported technical failure in 5 of 54 patients (9.3%).95 In the patients in whom dilation therapy is technically possible, sustained relief was reported in only 16% to 50% of patients,95,99 although most series100,101 have long-term successful outcomes in 70% of patients. No prospective or controlled studies are available. Postoperative strictures may occur at any site, including efferent and afferent limb anastomoses in patients with prior Billroth II surgery and at gastric bypass sites for bariatric surgery. A report of fluoroscopic balloon dilation of gastric outlet obstruction after surgery for morbid obesity stated 50% of 28 patients experienced relief of symptoms.102 The successful combined use of electrosurgical incision and balloon dilation was reported in five patients with refractory postoperative pyloric stenosis.103

Other causes of stomach or pyloric stenoses include a history of corrosive ingestion, prior radiation therapy, and Crohn’s disease (Box 17.1). Three patients with gastric outlet obstruction resulting from prior corrosive ingestion were treated successfully with intralesional steroid injections combined with TTS balloon dilation.104 There are several reports of balloon dilation for obstructive gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease (Video 17.1).105–107![]() Initial symptomatic relief is obtained, although a high rate of recurrence is reported. Repeat dilations may be required if there is a strong interest in avoiding surgery. Long fibrous strictures resulting from Crohn’s disease seem less likely to respond to endoscopic treatment.

Initial symptomatic relief is obtained, although a high rate of recurrence is reported. Repeat dilations may be required if there is a strong interest in avoiding surgery. Long fibrous strictures resulting from Crohn’s disease seem less likely to respond to endoscopic treatment.

Contraindications and Complications

Contraindications to balloon dilation include deep ulceration at the stenosis or uncorrectable coagulopathy. Although reported series are too small to assess the risk of active ulceration in the stricture, it is presumed that this does increase the risk of perforation. Perforation rates of 4% to 7.4% have been reported in small case series.95,100 In one study of 54 patients, two of the four perforations occurred in patients with active ulceration, and all four occurred with large balloon diameters (16 mm and 20 mm).95

One frequently reported adverse outcome is ulcer and stricture recurrence. One retrospective review of 19 patients who had undergone balloon dilation for nonmalignant pyloric stenoses with a median follow-up of 45 months found that all patients had immediate symptomatic relief but that only 16% experienced sustained relief.99 Symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction recurred in 84% of patients with the median time to recurrence being 9 months. NSAID intake was not studied in this group of patients with relapse; it was noted that recurrence was more likely in women.

In another series of 41 patients treated successfully with TTS dilation, only 14 patients (30%) remained disease-free at 3 years of follow-up.98 Subsequent surgery was required in 21 patients; 18 patients underwent surgery for recurrent obstructions, 2 for interval perforations, and 1 for bleeding. These outcomes have led some experts to recommend initial surgical treatment for patients who are good operative candidates. In contrast, prolonged symptom relief is reported in up to two-thirds of treated patients, especially if they continue acid suppressive therapy.100 It is reasonable to discuss these outcomes and potential complications with patients and to include them in the decision of trying endoscopic dilation treatment before surgery. Another possible adverse outcome of endoscopic dilation of gastric or duodenal stenoses is the potential for misdiagnosis of malignant obstruction resulting in delay in treatment.95

Benign Colonic and Ileocolonic Strictures

Similar to gastroduodenal strictures, the most important initial treatment decision for colonic and ileocolonic strictures is whether one should attempt balloon dilation or proceed directly to surgical treatment. This decision depends on the etiology of the stricture and the patient’s wishes. An important caveat is that only symptomatic strictures require treatment. Many colonic strictures noted at colonoscopy are not causing obstructive symptoms and are best left untreated. TTS balloon dilators are available for use during colonoscopy. They are the same length (3 to 4 cm) as pyloric dilation balloons and are often marketed for both locations being sufficiently long for the colonoscope. CRE and TTS balloons are available in the standard 18-Fr to 54-Fr sizes, although larger “anastomotic” balloons at 20 mm (60-Fr) and 25 mm (75-Fr) are also available. Some data support a higher clinical success for colonic dilation when balloons of greater diameter than 51-Fr are used.108 Successful radiologically guided balloon dilation has also been reported in lower GI tract strictures, as has dilation with polyvinyl over-the-guidewire dilators.109,110 Case reports using SEMS in benign colonic strictures are available,111 although use of SEMS is not routinely recommended because of the long-term patency problems associated with permanent metal stents in the GI tract.112

Causes of Benign Lower Gastrointestinal Tract Strictures

The most common site for lower GI tract strictures is at surgical anastomoses. Etiologies of benign lower GI stenoses include postoperative Crohn’s disease (most of which occur at previous surgical anastomotic sites), diverticular, ischemic, NSAID-related colopathy, and radiation-induced (Box 17.2). More than 150 patients with lower GI strictures caused by Crohn’s disease treated with endoscopic balloon dilation have been reported in case series.113–117 No controlled studies are available. Most strictures occur at previous surgical anastomoses, although de novo Crohn’s strictures have also been treated (Fig. 17.3). In the one prospective study of 55 patients submitted to 78 dilation procedures, the procedure was technically successful in 70 (90%).114 The 13.6-mm diameter colonoscope was successfully passed through the stricture immediately after the dilation in 73% of the dilations. Another large retrospective case series reported that the median number of dilations per patient was one, although many patients underwent two or three sessions.115 Long-term clinical benefit is reported in 41% to 62% of larger series114,115 and 72% to 80% in some smaller ones.116,117 There are three case series of combined local steroid injection and balloon dilation for a total of 44 patients.118–120 The response rate from this combined therapy is similar to other series of balloon dilation alone. However, a more recent pilot study of intrastricture steroid versus placebo injection after balloon dilation showed that local steroid injection did not reduce the time to repeat dilation. In the steroid arm, there was a trend toward earlier time to stricture relapse.121 It is difficult to know if adding local steroid injection improves clinical outcome.

Sedation delivered by an anesthetist has been used for some procedures, but most patients have standard conscious sedation. Complications seem to occur infrequently with balloon dilation of strictures caused by Crohn’s disease. Perforation has been the major concern and was reported in 1.6% to 8% of procedures. Colonic perforation usually requires surgical repair; however, this is not a dreaded outcome because surgery in a prepared bowel is the alternative treatment required for failure of treatment. However, the potential for perforation and surgical repair emphasizes the importance of not performing endoscopic dilation unless the lower GI stricture is symptomatic. Balloon dilation treatment of postoperative colorectal anastomotic strictures has been reported in more than 120 patients.108,122–124 None of these are prospective or controlled trials; all are case series. Success rates seem to be slightly better than stricture dilation in Crohn’s disease, although this may simply be reporting bias. Complications of perforation and bleeding occur in up to 7.8% of patients.108 Refractory strictures have been treated with a combination of balloon dilation and endoscopic incision with an electrocautery needle-knife (6 patients) or with balloon dilation and endoscopic laser treatment (10 patients).125,126 The success rate in both of these small series was 80% to 90%.

An alternative treatment was reported by Schubert and colleagues,127 who used electrosurgical incisions and argon plasma coagulation to treat postoperative GI strictures with a 100% success rate at 23-month (mean) follow-up. Of the 49 patients treated, only 4 patients required more than one session of treatment to allow passage of a Fujinon videocolonoscope (diameter 12 mm, operative channel 3.2 mm; Fujinon). NSAID colopathy can also lead to colonic strictures, often with a “diaphragm-type” appearance.128–130 These strictures are usually in the right colon and often are not narrow enough to cause obstructive symptoms. Multiple case reports exist, however, of successful balloon dilation as a viable option to surgical resection for tight NSAID strictures (Fig. 17.4). Discontinuation of NSAIDs is an important part of therapy. Radiation-induced colorectal strictures are some of the most challenging stenoses to treat. Surgical management carries a high mortality, unless simple bypass with colostomy or ileostomy is performed. For this reason, endoscopic dilation has been attempted with Savary-Gilliard dilators,131 balloon dilators,132 and permanent metal stent placement.133 The decision for the type of treatment for radiation strictures should be made after surgical consultation and careful consideration of patient wishes.

NSAID colopathy can also lead to colonic strictures, often with a “diaphragm-type” appearance.128–130 These strictures are usually in the right colon and often are not narrow enough to cause obstructive symptoms. Multiple case reports exist, however, of successful balloon dilation as a viable option to surgical resection for tight NSAID strictures (see Fig. 17-4). Discontinuation of NSAIDs is an important part of therapy.

Radiation-induced colorectal strictures are some of the most challenging stenoses to treat. Surgical management carries a high mortality, unless simple bypass with colostomy or ileostomy is performed. For this reason, endoscopic dilation has been attempted with Savary-Gilliard dilators,131 balloon dilators,132 and permanent metal stent placement.133 The decision for the type of treatment for radiation strictures should be made after surgical consultation and careful consideration of patient wishes.

1 Spechler SJ. AGA technical review on treatment of patients with dysphagia caused by benign disorders of the distal esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:223-254.

2 Dakkak M, Hoare RC, Maslin SC, et al. Oesophagitis is as important as oesophageal stricture diameter in determining dysphagia. Gut. 1993;34:152-155.

3 Marks RD, Richter JE, Rizzo H, et al. Omeprazole versus H2-receptor antagonists in treating patients with peptic stricture and esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:907-915.

4 Barbezat GO, Schlup M, Lubcke R. Omeprazole therapy decreases the need for dilatation of peptic oesophageal strictures. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1041-1045.

5 Agnew SR, Pandya SP, Reynolds RP, et al. Predictors for frequent esophageal dilations of benign peptic strictures. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:931-936.

6 Broor SL, Kumar A, Chari ST, et al. Corrosive esophageal strictures following acid ingestion: Clinical profile and results of endoscopic dilatation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1989;4:56-61.

7 Wilcox CM. Esophageal strictures complicating ulcerative esophagitis in patients with AIDS. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:339-343.

8 Colina RE, Smith M, Kikendall JW, et al. A new probable increasing cause of esophageal ulceration: Alendronate. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:704-706.

9 Maddern JG, Horowitz M, Jamieson GG, et al. Abnormalities of esophageal and gastric emptying in progressive systemic sclerosis. Gastroenterology. 1984;97:922-926.

10 Desai TK, Stecevic V, Chang CH, et al. Association of eosinophilic inflammation with esophageal food impaction in adults. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:795-801.

11 Stork T, Gareis R, Krumholz K, et al. Aberrant right subclavian artery (arteria lusoria) as a rare cause of dysphagia and dyspnea in a 79-year-old woman with right mediastinal and retrotracheal mass, and co-existing coronary artery disease. Vasa. 2001;30:225-228.

12 Woods RK, Sharp RJ, Holcomb GW3rd, et al. Vascular anomalies and tracheoesophageal compression: A single institution’s 25-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:434-438.

13 Standards of Practice Committee Egan JV, Baron TH, Adler DG, et al. Esophageal dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:755-760.

14 McClave SA, Brady PG, Wright RA, et al. Does fluoroscopic guidance for Maloney esophageal dilation impact on the clinical endpoint of therapy: Relief of dysphagia and achievement of luminal patency. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:93-97.

15 Tucker LE. The importance of fluoroscopic guidance for Maloney dilation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:1709-1711.

16 Kozarek RA, Patterson DJ, Ball TJ, et al. Esophageal dilation can be done safely using selective fluoroscopy and single dilation sessions. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;20:184-188.

17 Goldstein JA, Barkin JS. Comparison of the diameter consistency and dilating force of the controlled radial expansion balloon catheter to the conventional balloon dilators. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3423-3427.

18 McLean GK, LeVeen RF. Shear stress in the performance of esophageal dilation: Comparison of balloon dilation and bougienage. Radiology. 1989;172:983-986.

19 Abele JE. The physics of esophageal dilatation. Hepatogastroenterology. 1992;39:486-489.

20 Saeed ZA, Winchester CB, Ferro PS, et al. Prospective randomized comparison of polyvinyl bougies and through-the-scope balloons for dilation of peptic strictures of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:189-195.

21 Scolapio JS, Pasha TM, Gostout CJ, et al. A randomized prospective study comparing rigid to balloon dilators for benign esophageal strictures and rings. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:13-17.

22 Hernandez LJ, Jacobson JW, Harris MS. Comparison among the perforation rates of Maloney, balloon, and Savary dilation of esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:460-462.

23 Cox JG, Winter RK, Maslin SC, et al. Balloon or bougie for dilatation of benign oesophageal stricture? An interim report of a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 1988;29:1741-1747.

24 Tytgat GN. Dilation therapy of benign esophageal stenoses. World J Surg. 1989;13:142-148.

25 Shemesh E, Czerniak A. Comparison between Savary-Gilliard and balloon dilatation of benign esophageal strictures. World J Surg. 1990;14:518-521.

26 Yamamoto H, Hughes RWJr, Schroeder KW, et al. Treatment of benign esophageal stricture by Eder-Puestow or balloon dilators: A comparison between randomized and prospective nonrandomized trials. Mayo Clin Proc. 1992;67:228-236.

27 Tulman AB, Boyce HWJr. Complications of esophageal dilation and guidelines for their prevention. Gastrointest Endosc. 1981;27:229-234.

28 Bautista-Casanovas A, Varela-Cives R, Estevez Martinez E, et al. What is the infection risk of oesophageal dilatations? Eur J Pediatr. 1998;157:901-903.

29 ASGE Standards of Practice CommitteeBanerjee S, Shen B, Baron TH, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:791-798.

30 Pereira-Lima JC, Ramires RP, Zamin IJr, et al. Endoscopic dilation of benign esophageal strictures: Report on 1043 procedures. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1497-1501.

31 Dumon JF, Meric B, Sivak MVJr, et al. A new method of esophageal dilation using Savary-Gilliard bougies. Gastrointest Endosc. 1985;31:379-382.

32 Kozarek RA, Patterson DJ, Ball TJ, et al. Esophageal dilation can be done safely using selective fluoroscopy and single dilating sessions. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;20:184-188.

33 Silvis SE, Nebel O, Rogers G, et al. Endoscopic complications: Results of the 1974 American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy survey. JAMA. 1976;235:928-930.

34 Kozarek RA. Hydrostatic balloon dilation of gastrointestinal stenoses: A national survey. Gastrointest Endosc. 1986;32:15-19.

35 Zuccaro GJr, Richter JE, Rice TW, et al. Viridans streptococcal bacteremia after esophageal stricture dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:568-573.

36 Nelson DB, Sanderson SJ, Azar MM. Bacteremia with esophageal dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:563-567.

37 Hirota WK, Wortmann GW, Maydonovitch CL, et al. The effect of oral decontamination with clindamycin palmitate on the incidence of bacteremia after esophageal dilation: A prospective trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:475-479.

38 Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: Guidelines from the American Heart Association: A guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee; American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation, 116. 1736-1754:2007.

39 Ogilvie AL, Ferguson R, Atkinson M. Outlook with conservative treatment of peptic oesophageal stricture. Gut. 1980;21:23-25.

40 Hands LJ, Papavramidis S, Bishop H, et al. The natural history of peptic oesophageal stricture treated by dilation and anti-reflux therapy alone. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1989;71:306-309.

41 Smith PM, Kerr GD, Cockel R, et al. A comparison of omeprazole and ranitidine in the prevention of recurrence of benign esophageal stricture. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1312-1318.

42 Said A, Brust DJ, Gaumnitz EA, et al. Predictors of early recurrence of benign esophageal strictures. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1252-1256.

43 Grobe JL, Kozarek RA, Sanowski RA. Self-bougienage in the treatment of benign esophageal strictures. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1984;6:109-112.

44 Duseja A, Chawla YK, Singh RP, et al. Dilatation of benign esophageal strictures: 10 year’s experience with Celestin dilators. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:26-29.

45 Lahoti D, Broor SL, Basu PP, et al. Corrosive esophageal strictures: Predictors of response to endoscopic dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:196-200.

46 Ikeya T, Ohwada S, Ogawa T, et al. Endoscopic balloon dilation for benign esophageal anastomotic stricture: Factors influencing its effectiveness. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:959-966.

47 Ramage JIJr, Rumalla A, Baron TH, et al. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of endoscopic steroid injection therapy for recalcitrant esophageal peptic strictures. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2419-2425.

48 Berenson GA, Wyllie R, Caulfield M, et al. Intralesional steroids in the treatment of refractory esophageal strictures. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1994;18:250-252.

49 Holder TM, Ashcraft KW, Leape L. The treatment of patients with esophageal strictures by local steroid injections. J Pediatr Surg. 1969;4:646-653.

50 Kirsch M, Blue M, Desai RK, et al. Intralesional steroid injections for peptic esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:180-182.

51 Zein NN, Greseth JM, Perrault J. Endoscopic intralesional steroid injections in the management of refractory esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:596-598.

52 Lee M, Kubik CM, Polhamus CD, et al. Preliminary experience with endoscopic intralesional steroid injection therapy for refractory upper gastrointestinal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:598-601.

53 Kochhar R, Ray JD, Sriram PV, et al. Intralesional steroids augment the effects of endoscopic dilation in corrosive esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:509-513.

54 Brandimarte G, Tursi A. Endoscopic treatment of benign anastomotic esophageal stenosis with electrocautery. Endoscopy. 2002;34:399-401.

55 Hordijk ML, Siersema PD, Tilanus HW, et al. Electrocautery therapy for refractory anastomotic strictures of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:157-163.

56 Hagiwara A, Togawa T, Yamasaki J, et al. Endoscopic incision and balloon dilatation for cicatricial anastomotic strictures. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:997-999.

57 Schubert D, Kuhn R, Lippert H, et al. Endoscopic treatment of benign gastrointestinal anastomotic strictures using argon plasma coagulation in combination with diathermy. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1579-1582.

58 Shah JN. Benign refractory esophageal strictures: Widening the endoscopist’s role. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:164-167.

59 Beilstein MC, Kochman ML. Endoscopic incision of a refractory esophageal stricture: Novel management with an endoscopic scissors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:623-625.

60 Little AG, Naunheim KS, Ferguson MK, et al. Surgical management of esophageal strictures. Ann Thorac Surg. 1988;45:144-147.

61 Spechler SL. Comparison of medical and surgical therapy for complicated gastroesophageal reflux disease in veterans. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:786-792.

62 Spechler SJ, Lee E, Ahnen D, et al. Long-term outcome of medical and surgical therapies for gastroesophageal reflux disease: Follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:2331-2338.

63 Poirier NC, Taillerfer R, Topart R, et al. Antireflux operations in patients with scleroderma. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;58:66-72.

64 Fiorini A, Fleischer D, Valero J, et al. Self-expanding metal coil stents in the treatment of benign esophageal strictures refractory to conventional therapy: A case series. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:259-262.

65 Ackroyd R, Watson DI, Devitt PG, et al. Expandable metallic stents should not be used in the treatment of benign esophageal strictures. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:484-487.

66 Lee JG, Hsu R, Leung JW. Are self-expanding metal mesh stents useful in the treatment of benign esophageal stenoses and fistulas? An experience of four cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1857-1859.

67 Repici A, Conio M, De Angelis C, et al. Temporary placement of an expandable polyester silicone-covered stent for treatment of refractory benign esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:513-519.

68 Siersema PD. Stenting for benign esophageal strictures. Endoscopy. 2009;41:363-373.

69 Holm AN, de la Mora Levy JG, Gostout CJ, et al. Self-expanding plastic stents in treatment of benign esophageal conditions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:20-25.

70 Freeman ML. Bioabsorbable stents for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Tech Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;3:120-125.

71 Goldin E, Fiorini A, Ratan Y, et al. A new biodegradable and self-expanding stent for benign esophageal strictures [abstract]. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:294.

72 Fry SW, Fleischer DE. Management of a refractory benign esophageal stricture with a new biodegradable stent. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:179-182.

73 Saito Y, Tanaka T, Andoh A, et al. Usefulness of biodegradable stents constructed of poly-l-lactic acid monofilaments in patients with benign esophageal stenosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3977-3980.

74 DeVault KR. Lower esophageal (Schatzki’s) ring: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Dig Dis. 1996;14:323-329.

75 Hirano I, Gilliam J, Goyal RK. Clinical and manometric features of the lower esophageal muscular ring. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:43-49.

76 Johnson AC, Lester DD, Johnson S, et al. Esophagogastric ring: Why and when we see it, and what it implies: A radiologic-pathologic correlation. South Med J. 1992;85:946-952.

77 Marshall JB, Kretschmar JM, Diaz-Arias AA. Gastroesophageal reflux as a pathogenic factor in the development of symptomatic lower esophageal rings. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1669-1672.

78 Sgouros SN, Vlachogiannakos J, Karamanolis G, et al. Long-term acid suppressive therapy may prevent the relapse of lower esophageal (Schatzki’s) rings: A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1929-1934.

79 Chotiprasidhi P, Minocha A. Effectiveness of single dilation with Maloney dilator versus endoscopic rupture of Schatzki ring using biopsy forceps. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:281-284.

80 Guelrud M, Villasmil L, Mendez R. Late results in patients with Schatzki ring treated by endoscopic electrosurgical incision of the ring. Gastrointest Endosc. 1987;33:96-98.

81 Burdick JS, Venu RP, Hogan WJ. Cutting the defiant lower esophageal ring. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:616-619.

82 Ibrahim A, Cole RA, Qureshi WA, et al. Schatzki’s ring: To cut or break an unresolved problem. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:379-383.

83 DiSario JA, Pedersen PJ, Bichis-Canoutas C, et al. Incision of recurrent distal esophageal (Schatzki) ring after dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:244-248.

84 Wills JC, Hilden K, Disario JA, et al. A randomized, prospective trial of electrosurgical incision followed by rabeprazole versus bougie dilation followed by rabeprazole of symptomatic esophageal (Schatzki’s) rings. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:808-813.

85 Minocha A. Treatment of Schatzki’s ring. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1191.

86 Sreenivas DV, Kumar A, Mannar KV, et al. Results of Savary-Gilliard dilatation in the management of cervical web of esophagus. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:188-190.

87 Noel RJ, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic esophagitis. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2005;17:690-694.

88 Teitelbaum JE, Fox VL, Twarog FJ, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children: Immunopathological analysis and response to fluticasone propionate. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1216-1225.

89 Vasilopoulos S, Murphy P, Auerbach A, et al. The small-caliber esophagus: An unappreciated cause of dysphagia for solids in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:99-106.

90 Croese J, Fairley SK, Masson JW, et al. Clinical and endoscopic features of eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:516-522.

91 Desai TK, Stecevic V, Chang CH, et al. Association of eosinophilic inflammation with esophageal food impaction in adults. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:795-801.

92 Odze RD. Pathology of eosinophilic esophagitis: What the clinician needs to know. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:485-490.

93 Kaplan M, Mutlu EA, Jakate S, et al. Endoscopy in eosinophilic esophagitis: “feline” esophagus and perforation risk. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1:433-437.

94 Straumann A, Rossi L, Simon HU, et al. Fragility of the esophageal mucosa: a pathognomonic endoscopic sign of primary eosinophilic esophagitis? Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:407-412.

95 Lau JY, Chung SC, Sung JJ, et al. Through-the-scope balloon dilation for pyloric stenosis: Long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:98-101.

96 Pai CG. Use of Savary-Gilliard dilators for strictures of the distal stomach and duodenal bulb. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:866-867.

97 Gibson JB, Behrman SW, Fabian TC, et al. Gastric outlet obstruction resulting from peptic ulcer disease requiring surgical intervention is infrequently associated with Helicobacter pylori infection. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:32-37.

98 Hewitt PM, Krige JE, Funnell IC, et al. Endoscopic balloon dilatation of peptic pyloroduodenal strictures. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28:33-35.

99 Kuwada SK, Alexander GL. Long-term outcome of endoscopic dilation of nonmalignant pyloric stenosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:15-17.

100 Kozarek RA, Botoman VA, Patterson DJ. Long-term follow-up in patients who have undergone balloon dilation for gastric outlet obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:558-561.

101 Boylan JJ, Gradzka MI. Long-term results of endoscopic balloon dilatation for gastric outlet obstruction. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:1883-1886.

102 Vance PL, deLange EE, Shaffer HAJr, et al. Gastric outlet obstruction following surgery for morbid obesity: Efficacy of fluoroscopically guided balloon dilation. Radiology. 2002;222:70-72.

103 Hagiwara A, Sonoyama Y, Togawa T, et al. Combined use of electrosurgical incisions and balloon dilatation for the treatment of refractory postoperative pyloric stenosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:504-508.

104 Kochhar R, Sriram PV, Ray JD, et al. Intralesional steroid injections for corrosive induced pyloric stenosis. Endoscopy. 1998;30:734-736.

105 Kelly SM, Hunter JO. Endoscopic balloon dilatation of duodenal strictures in Crohn’s disease. Postgrad Med J. 1995;71:623-624.

106 Matsui T, Hatakeyama S, Ikeda K, et al. Long-term outcome of endoscopic balloon dilation in obstructive gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease. Endoscopy. 1997;29:640-645.

107 Kimura H, Sugita A, Nishiyama K, et al. Treatment of duodenal Crohn’s disease with stenosis: Case report of 6 cases. Jpn J Gastroenterol. 2000;97:697-702.

108 Kozarek RA. Hydrostatic balloon dilation of gastrointestinal stenoses: A national survey. Gastrointest Endosc. 1986;32:15-19.

109 McNicholas MM, Gibney RG, MacErlaine DP. Radiologically guided balloon dilatation of obstructing gastrointestinal strictures. Abdom Imaging. 1994;19:102-107.

110 Morini S, Hassan C, Cerro P, et al. Management of an ileocolonic anastomotic stricture using polyvinyl over-the-guidewire dilators in Crohn’s disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:384-387.

111 Cascales-Sanchez P, Garcia-Olmo D, Julia-Molla E. Long-term expandable stent as a definitive treatment for benign rectal stenosis. Br J Surg. 1997;84:840-841.

112 Kozarek RA, Ball TJ, Patterson DJ. Metallic self-expanding stent application in the upper gastroesophageal tract: Caveats and concerns. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:1-6.

113 Breysem Y, Coremans G, Hendrickx G. Endoscopic balloon dilation of colonic and ileo-colonic Crohn’s strictures: Long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:142-147.

114 Couckuyt H, Gevers AM, Coremans G, et al. Efficacy and safety of hydrostatic balloon dilatation of ileocolonic Crohn’s strictures: A prospective longterm analysis. Gut. 1995;36:577-580.

115 Thomas-Gibson S, Brooker JC, Hayward CM, et al. Colonoscopic balloon dilation of Crohn’s strictures: A review of long-term outcomes. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:485-488.

116 Dear KL, Hunter JO. Colonoscopic hydrostatic balloon dilatation of Crohn’s strictures. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:315-318.

117 Williams AJ, Palmer KR. Endoscopic balloon dilatation as a therapeutic option in the management of intestinal stricture resulting from Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg. 1991;78:453-454.

118 Brooker JC, Beckett CG, Saunders BP, et al. Long-acting steroid injection after endoscopic dilation of anastomotic Crohn’s strictures may improve the outcome: A retrospective case series. Endoscopy. 2003;35:333-337.

119 Ramboer C, Verhamme M, Dhondt E, et al. Endoscopic treatment of stenosis in recurrent Crohn’s disease with balloon dilation combined with local corticosteroid injection. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:252-255.

120 Singh VV, Draganov P, Valentine J. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic balloon dilation of symptomatic upper and lower gastrointestinal Crohn’s disease strictures. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:284-290.

121 East JE, Brooker JC, Rutter MD, et al. A pilot study of intrastricture steroid versus placebo injection after balloon dilatation of Crohn’s strictures. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1065-1069.

122 Venkatesh KS, Ramanujam PS, McGee S. Hydrostatic balloon dilatation of benign colonic anastomotic strictures. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:789-791.

123 Skreden K, Wiig JN, Myrvold HE. Balloon dilation of rectal strictures. Acta Chir Scand. 1987;153:615-617.

124 Aston NO, Owen WJ, Irving JD. Endoscopic balloon dilatation of colonic anastomotic strictures. Br J Surg. 1989;76:780-782.

125 Hagiwara A, Togawa T, Yamasaki J, et al. Endoscopic incision and balloon dilatation for cicatricial anastomotic strictures. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:997-999.

126 Luck A, Chapius P, Sinclair G, et al. Endoscopic laser stricturotomy and balloon dilatation for benign colorectal strictures. Aust N Z J Surg. 2001;71:594-597.

127 Schubert D, Kuhn R, Lippert H, et al. Endoscopic treatment of benign gastrointestinal anastomotic strictures using argon plasma coagulation in combination with diathermy. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1579-1582.

128 Gopal DV, Katon RM. Endoscopic balloon dilation of multiple NSAID-induced colonic strictures: Case report and review of the literature on NSAID-related colopathy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:120-123.

129 Weinstock LB, Hammoud Z, Brandwin L. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced colonic stricture and ulceration treated with balloon dilatation and prednisone. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:564-566.

130 Smith JA, Pineau BC. Endoscopic therapy of NSAID-induced colonic diaphragm disease: Two cases and a review of published reports. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:120-125.

131 Triadafilopoulos G, Sarkisian M. Dilatation of radiation-induced sigmoid stricture using sequential Savary-Gilliard dilators: A combined radiologic-endoscopic approach. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:1065-1067.

132 Johansson C. Endoscopic dilation of rectal strictures: A prospective study of 18 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:423-428.

133 Yates MR, Baron TH. Treatment of a radiation-induced sigmoid stricture with an expandable metal stent. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:422-426.