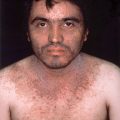

Chapter 41 Benign melanocytic tumors

Grichnik J: Melanoma, nevogenesis, and stem cell biology, J Invest Dermatol 128:2365–2380, 2008.

Snow TM: Mongolian spots in the newborn: do they mean anything? Neonatal Netw 24:31–33, 2005.

Takata M., Saida, T: Genetic alterations in melanocytic tumors, J Dermatol Sci 43:1–10, 2006.

Naeyaert JM, Brochez L: Clinical practice. Dysplastic nevi. N Engl J Med 349:2233–2240, 2003.

Elder DE: Dysplastic naevi: an update, Histopathology 56:112–120, 2010.

Despite the above findings, as well as the documented increased risk of melanoma in patients with atypical nevi, it is important to recognize that most atypical nevi are benign and do not progress to melanoma. In this regard, previous studies have shown that anywhere from 20% to 40% of melanomas arise from a preexisting nevus, 30% to 70% arise de novo and, in almost a quarter, the historical origin cannot be assessed. Therefore, although there is a clear association between nevi and melanoma risk, at present it is not clear whether an atypical nevus is more likely to develop into a melanoma than any other type of nevus. Moreover, it is quite clear that a nevus precursor is not required for the majority of melanomas. It is thought that the discrepancy between melanomas arising in preexisting nevi and de novo melanomas can best be explained by the cancer stem cell theory. In this regard, the risk of melanoma associated with nevi may be due to the potential for secondary mutations within nevi, as well as due to the inherent properties of the stem cell population in individuals with numerous moles.

Landau M, Krafchik BR: The diagnostic value of café-au-lait macules, J Am Acad Dermatol 40:877–890, 1999.

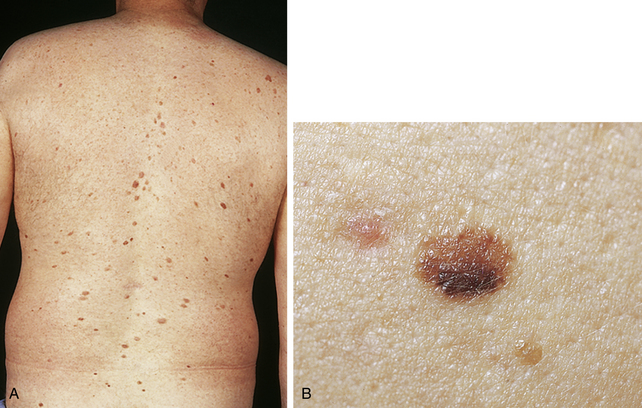

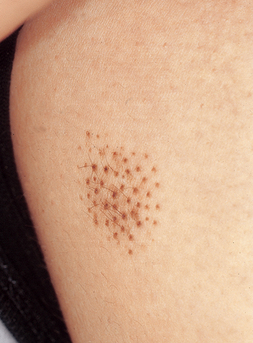

Figure 41-6. Nevus spilus showing a large café-au-lait macule with multiple small pigmented lesions.

Vaidya DC, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK: Nevus spilus, Cutis 80:465–468, 2007.