Chapter 68 Benign Lung Tumors*

Classification

Benign neoplastic tumors are classified histologically according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification updated in 2004 (Box 68-1). These histologic distinctions are more helpful to the pathologist than to the clinician approaching a lung tumor and are more likely to be in the “is it malignant or not” mindset. Although typically benign, many of the benign neoplasms have the potential for malignant transformation.

Benign Epithelial Neoplasms

Papillomas

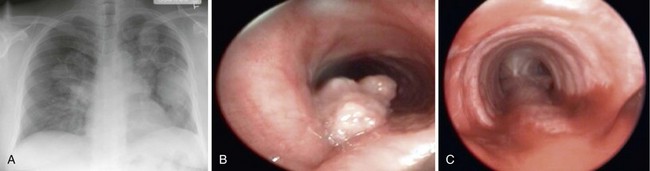

Benign epithelial neoplasms are generally rare, although squamous papilloma is the most common. Histologically, these are identified as papillary tumors with a squamous cell epithelial surface and delicate connective tissue attachments. They may be solitary or multiple and most often occur in the larynx and trachea, with less than 10% having lower airway involvement and only 2% within the lung parenchyma (Figure 68-1). The squamous type of papilloma has an association with human papillomavirus (HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, and 35). Obstructive symptoms may develop from airway involvement and are an indication for laryngoscopic or bronchoscopic removal. Recurrent papillomas occur in as many as 20%, and some patients require periodic endoscopic debridement. Malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma may occur. Compared with squamous cell papillomas, glandular and mixed-cell papillomas are exceedingly rare.

Benign Mesenchymal Neoplasms

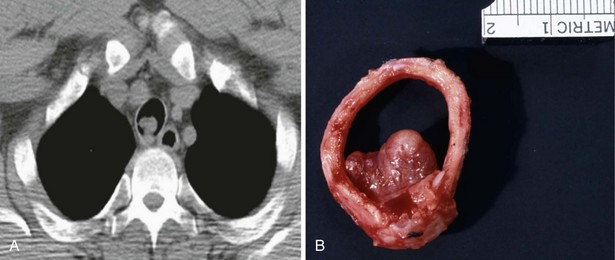

Chondroma

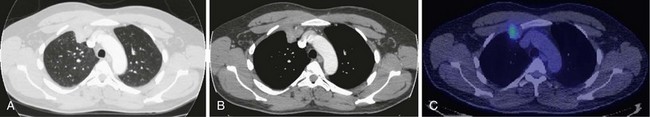

Chondromas are benign tumors composed of cartilage and are most often found in the patient with Carney triad: pulmonary chondroma, gastric stromal sarcoma, and paraganglioma. Although described as a “triad,” most patients will manifest only two different neoplasms. The appearance of chondromas on chest radiograph is usually diagnostic because these are typically multiple, well-circumscribed, calcified nodules occurring in young women (Figure 68-2). The main differential of the radiographic appearance of a chondroma is a hamartoma, typically singular. Chondromas are benign, and patients with Carney triad will more likely have symptoms from other, extrapulmonary manifestations.

Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor

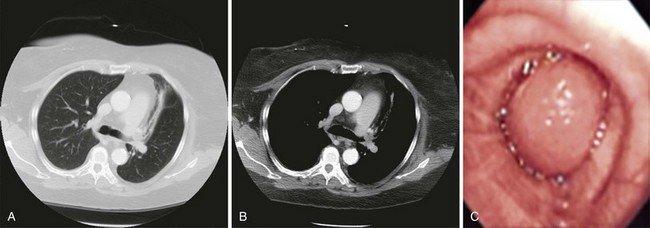

Synonyms for inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) include inflammatory pseudotumor, plasma cell granuloma, fibrous histiocytoma, and fibroxanthoma. IMT is composed of a mixture of inflammatory cells (with plasma cell predominance), collagen, and spindle cells showing myofibroblastic differentiation. IMTs are the most common benign primary lung tumor in children and usually occur in the airways. In adults these lesions are rare and more often present as solitary parenchymal masses (Figure 68-3). Symptoms may include weight loss and fatigue or pain relating to tumor location; chest wall invasion or angioinvasion can occur. Resection is the only proven treatment, and complete excision is usually curative, although recurrence after excision and metastases or progression to sarcoma can occur.

Neurofibromas

The neurofibromatoses (NFs) are autosomal dominant disorders and may be associated with benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors in the airway or lung (Figure 68-4). A retrospective study of 156 patients with NF found lung nodules or masses present in 5%, not including those with paraspinal or chest wall masses. Neurofibromas and schwannomas may also be present in the absence of NF, and there is the potential for malignant change. Clinical signs and symptoms typically relate to airway obstruction (cough, wheezing, dyspnea, hemoptysis).

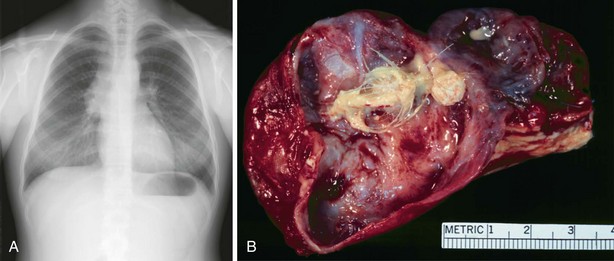

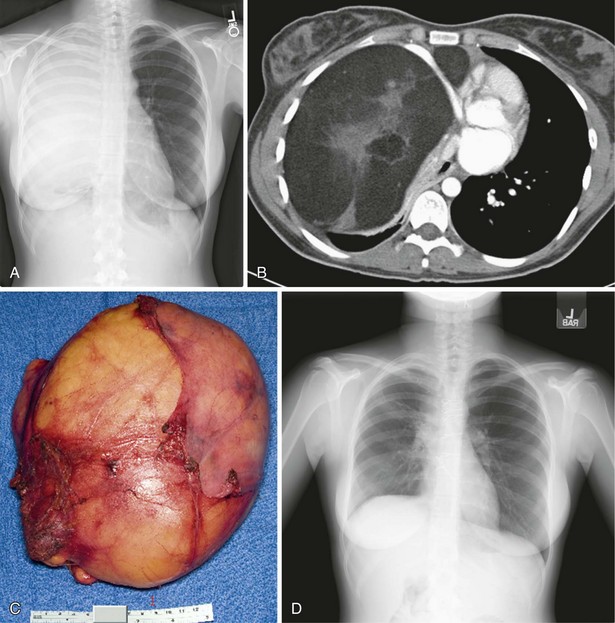

Solitary Fibrous Tumor of Pleura

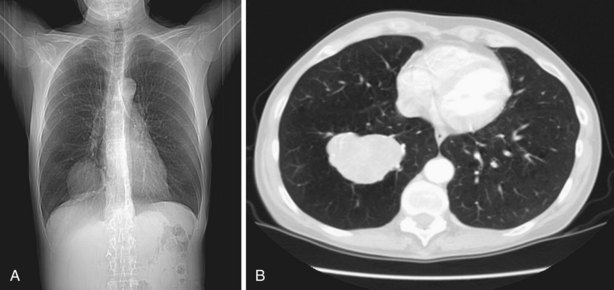

Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura (SFTPs) are spindle cell mesenchymal tumors. They typically arise in the visceral pleura, but also from lung parenchyma or mediastinum, and may become very large (Figure 68-5). The terminology of “benign mesothelioma” is no longer used. In one retrospective series of 84 patients, 55% were symptomatic (cough, chest pain, dyspnea); 4% had the paraneoplastic manifestations of hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy (HPO), 6% had HPO and clubbing, and 1% hypoglycemia. Rarely, SFTP can be malignant.

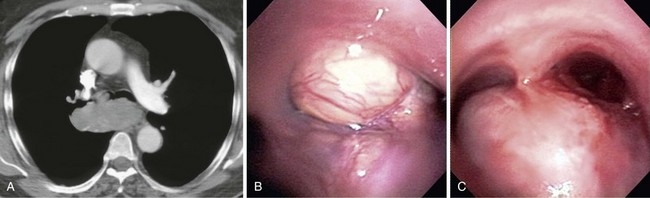

Glomus Tumor

Glomus tumors are extremely rare, occur more often in males, and are thought to be of glomus cellular origin, having the appearance of smooth muscle. Based on cellular appearance, they are further classified as classic glomus tumor, glomangioma, and glomangiomyoma. Within the chest, glomus tumors are more likely to be in the trachea, but they have been described in the lung and mediastinum (Figure 68-6). Successful resection has been reported with surgery or bronchoscopy, and malignant behavior has been observed.

Benign Neoplasms: Miscellaneous

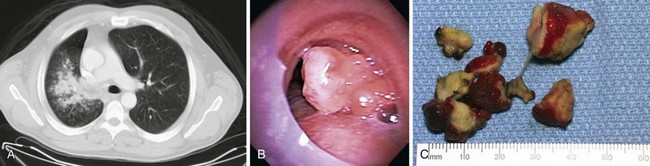

Hamartoma

Pulmonary hamartomas are the most common benign neoplasms in the lung, comprising cartilage, fat, connective tissue, and smooth muscle. Hamartomas are rare in children; in adults they are usually in the parenchyma, and approximately 10% present endobronchially (Figure 68-7). Patients with parenchymal hamartoma are usually asymptomatic, and typical features of fat and calcification may be evident on CT images. When lacking classic CT features, parenchymal hamartomas are often diagnosed at resection to exclude malignancy. Rarely, recurrence or sarcomatous transformation has been described.

Benign Teratoma

Teratomas are composed of tissues from more than one germ cell line and have mature and immature forms. Mature pulmonary teratomas are benign and more common in the upper lobes of the lung. Immature teratomas may be malignant. Because teratomas are frequently cystic and contain skin, hair, sweat glands, fat, bone, sebaceous material, or toothlike structures, some of these elements may be visible on CT scans. Patients with teratomas may be asymptomatic or may present with chest pain, hemoptysis, or the unusual symptom of trichoptysis, expectorating hair. Surgery is generally recommended, even if the diagnosis is evident from imaging studies (Figure 68-8).

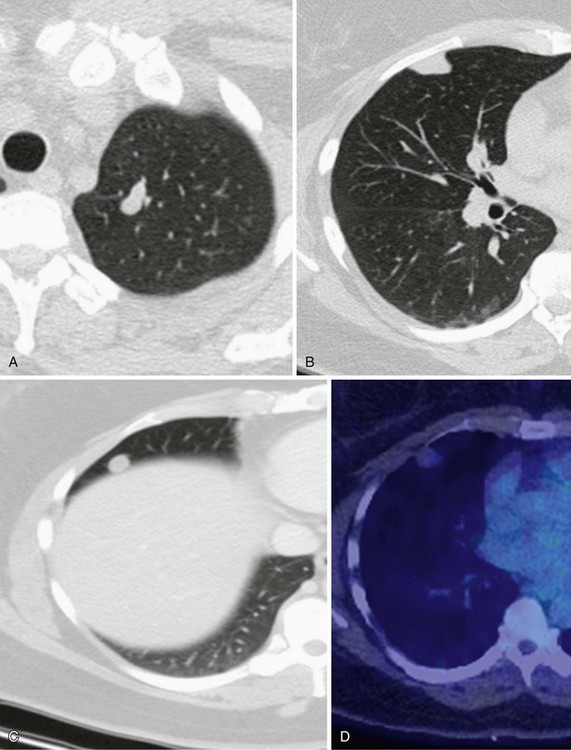

Leiomyoma

Leiomyomas are benign smooth muscle tumors occurring in women. When singular, and absent a history of uterine leiomyomas, they most often occur in the airway. Benign leiomyoma may also present in the lung of women with a history of uterine leiomyoma and is termed benign metastasizing leiomyoma (BML). BML is characterized by multiple, slow-growing, smooth muscle tumors (Figure 68-9). Despite the resemblance to malignancy, the number of mitotic indices is low, and there is no evidence of invasion despite multiple distant lesions. Extrauterine leiomyosarcoma must be excluded. The lung involvement in BML is typically evident 10 to 15 years after the removal of the uterine leiomyoma. BML is usually negative on PET imaging. Treatment includes hormonal therapy, surgical resection, and chemotherapy.

Lipoma

Lipomas are rare, are composed of mature fat cells, and may occur in the airway or less often in the mediastinum. Presenting symptoms depend on the size and location of the lesion, most often dyspnea and cough. CT imaging shows the lesion to be homogeneous and composed of fat (Figure 68-10). Local recurrence has been described after resection.

Non-Neoplastic Tumors

A variety of conditions cause benign lesions in the lung that are not true neoplasms (Box 68-2). These conditions need to be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating a nodule or mass on imaging studies and include nodular lymphoid hyperplasia, organizing pneumonia, endometriosis, rounded atelectasis, and sequestration, as discussed in earlier chapters.

Amyloid Deposits

As an example of a non-neoplastic tumor, amyloid is composed of a group of fibrillar proteins with beta-pleated-sheet formation, which demonstrates birefringence under polarized light on Congo red stain. Pulmonary manifestations of amyloidosis include tracheobronchial infiltration, persistent pleural effusions, parenchymal nodules, and amyloidomas (Figure 68-11). Amyloid deposits in the lung may or may not be associated with systemic amyloidosis.

Carney JA. Carney triad: a syndrome featuring paraganglionic, adrenocortical, and possibly other endocrine tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3656–3662.

Gaertner EM, Steinberg DM, Huber M, et al. Pulmonary and mediastinal glomus tumors: report of five cases including a pulmonary glomangiosarcoma—a clinicopathologic study with literature review. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1105–1114.

Gjevre JA, Myers JL, Prakash UB. Pulmonary hamartomas. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:14–20.

Harrison-Phipps KM, Nichols FC, Schleck CD, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura: results of surgical treatment and long-term prognosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:19–25.

Sakurai H, Hasegawa T, Watanabe S, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the lung. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;25:155–159.

Sakurai H, Kaji M, Yamazaki K, et al. Intrathoracic lipomas: their clinicopathological behaviors are not as straightforward as expected. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:261–265.

Shah H, Garbe L, Nussbaum E, et al. Benign tumors of the tracheobronchial tree: endoscopic characteristics and role of laser resection. Chest. 1995;107:1744–1751.

Travis WD, Brambilla E, Müller-Hermelink HK, et al. World Health Organization classification of tumors: pathology and genetics of tumors of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. ed 4. Geneva: WHO; 2004:78–121.

Utz JP, Swensen SJ, Gertz MA. Pulmonary amyloidosis: the Mayo Clinic experience from 1980 to 1993. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:407–413.

Zamora A, Collard H, Wolters P, et al. Neurofibromatosis-associated lung disease: a case series and literature review. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:210–214.