Benign Lesions of the Vaginal Wall

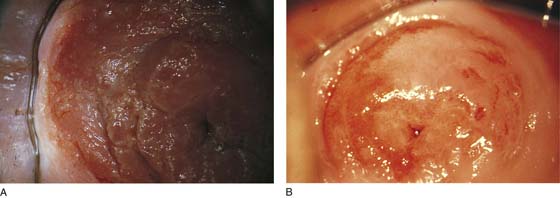

Under normal circumstances, the vagina does not contain any glands. However, when the condition of adenosis exists (i.e., occurs spontaneously or as the result of antenatal diethylstilbestrol [DES] exposure), mucosal and submucosal mucus-secreting glands may be identified (Fig. 60–1A, B). These lesions appear as granulation-like tissue, clefts, holes, or cysts (Fig. 60–2A, B). Whenever adenosis is suspected, the lesion should be biopsied to ensure that adenocarcinoma does not exist within or around it. Additionally, the risk of squamous intraepithelial neoplasia is increased because of the multiple squamocolumnar junctions exposed to environmental factors associated with coitus.

Biopsies

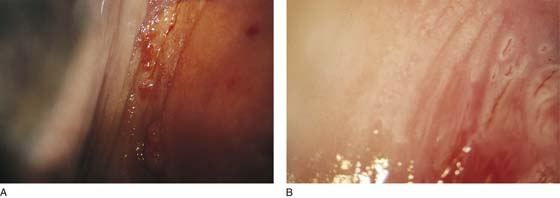

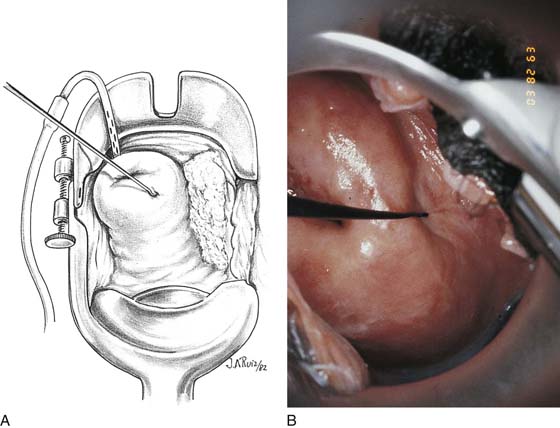

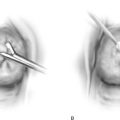

Vaginal biopsies are performed in a manner similar to that used for cervical disease (i.e., with a long-shanked biopsy forceps) (Fig. 60–3). Exposure can be a problem for vaginal lesions, and the use of a manipulating hook allows the examiner to properly display the lesion to colposcopic vision (Fig. 60–4A, B).

Cysts

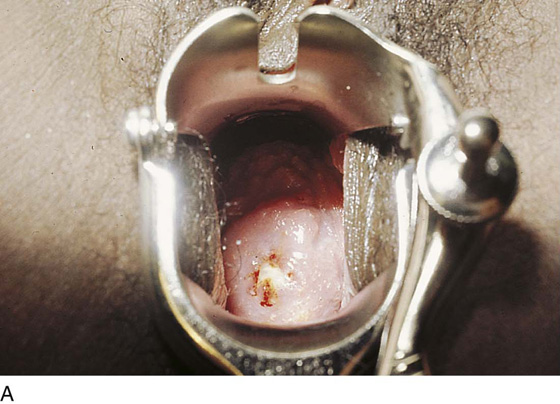

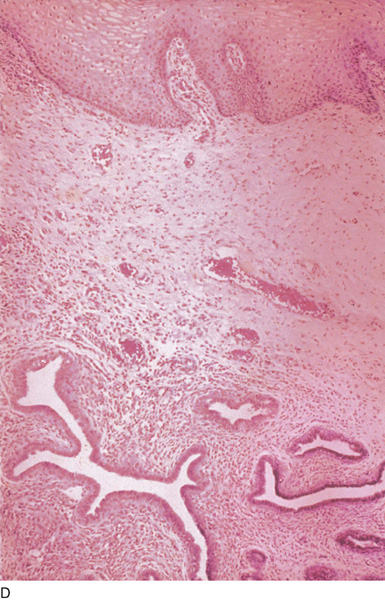

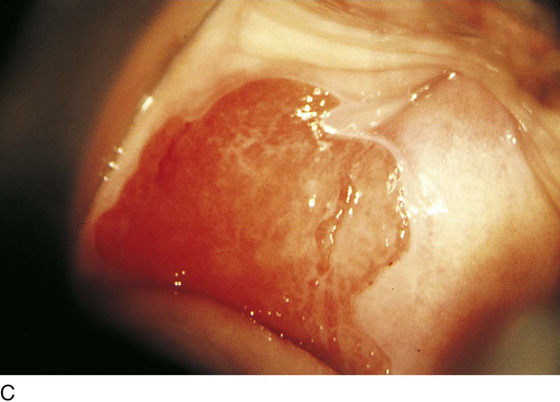

Cysts 2 cm or larger should be excised in the operating room with the patient under local or general anesthesia. Clearly, these lesions may run the gamut from mucous inclusions (adenosis), to squamous inclusions, to Gartner duct cysts (mesonephric remnants). Viewing a cyst from the vagina provides little insight as to its origin or potential risk(s). An unusual condition that produces small cysts—some up to 1 to 1.5 cm—is vaginitis emphysematosa. This condition is associated with multiple gas-filled spaces (Fig. 60–5A through D).

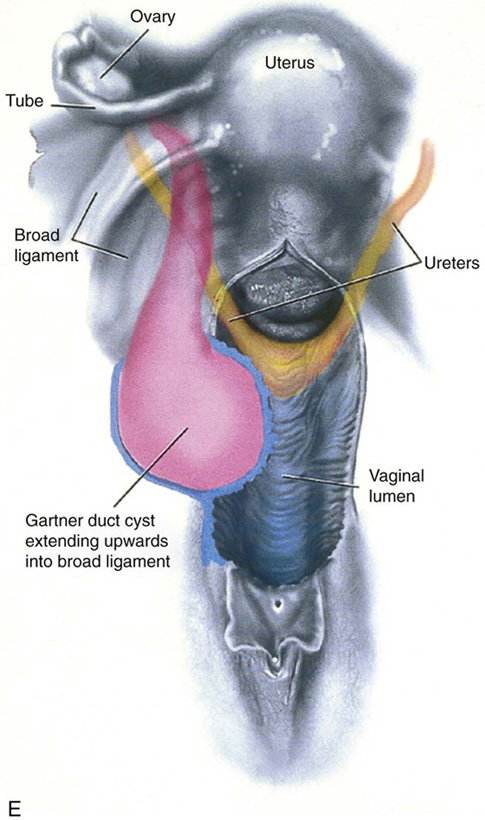

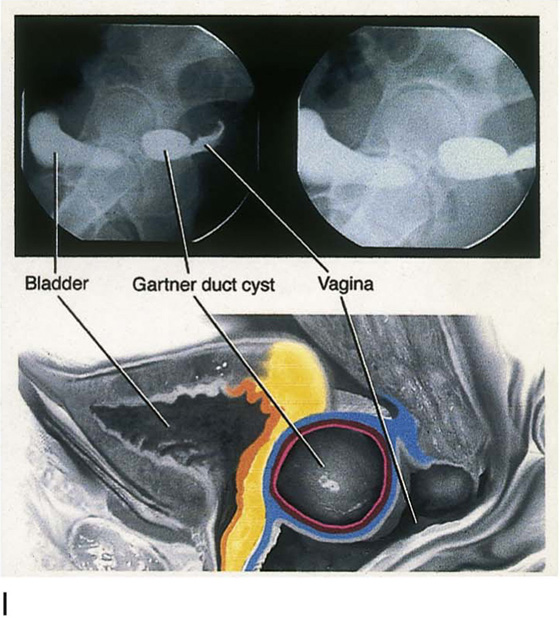

The Gartner duct (mesonephric) is found deep in the lateral wall of the vagina; although it may wander anteriorly or posteriorly, a cyst duct may extend cranially through the entire length of the vagina and via the cervix into the broad ligament (Fig. 60–6A through E). Before embarking on an operation to remove the cyst, it is important for the gynecologist to obtain as much preoperative information about the cyst and its neighboring structures as possible (Fig. 60–6F through H). The technique of excising any vaginal cyst is similar. The relationship of the cyst to the bladder and the ureter must be known (Fig. 60–6I). If necessary, the ureter should be catheterized.

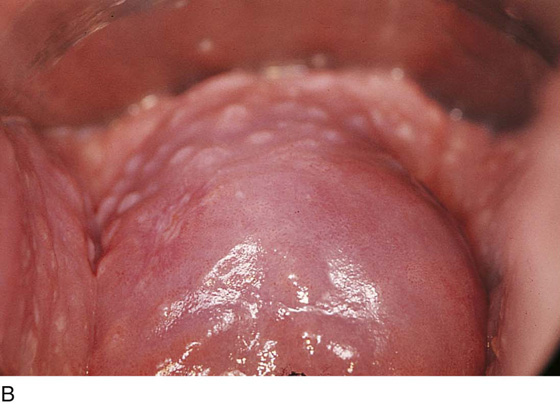

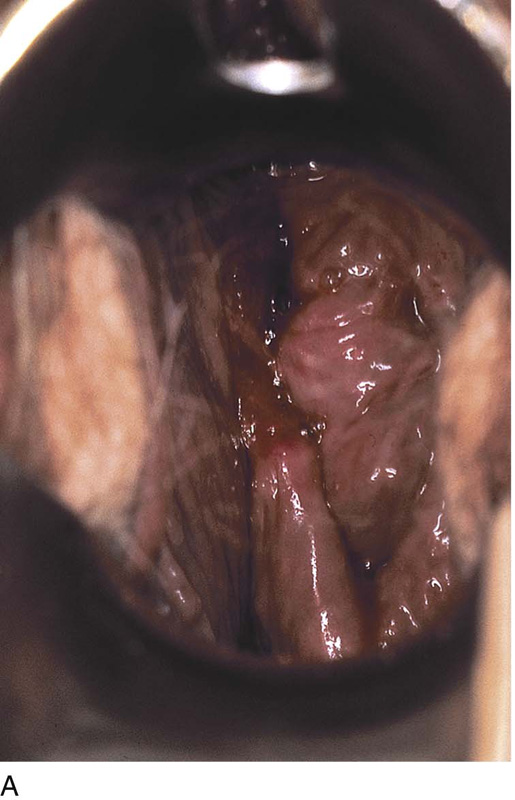

FIGURE 60–1 A. The cervix and the vagina of this diethylstilbestrol (DES)-exposed woman reveal total absence of a squamous epithelial covering of the ectocervix. The vaginal fornices likewise contain only glandular tissue. B. Another DES-exposed woman’s cervix and vagina show extensive squamous metaplasia (pink) interspersed with glandular tissue (red).

FIGURE 60–2 A. Granulation-like glandular tissue located in the lateral vaginal fornix is diagnostic of adenosis. B. Clefts and gland openings are apparent in this patient’s vagina. A biopsy into this area will reveal mucous glands beneath the surface squamous metaplastic epithelium.

FIGURE 60–3 A directed vaginal biopsy is performed under colposcopic guidance. Patients feel little, if any, discomfort if the biopsy is performed in a timely manner with a sharp biopsy clamp.

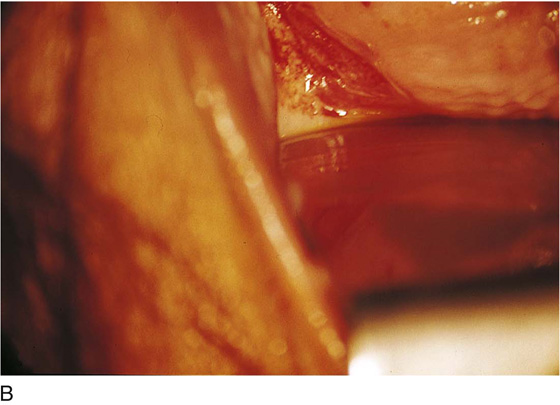

FIGURE 60–4 A. To expose the vaginal fornices to facilitate a directed biopsy, a long-handled titanium hook pulls the cervix out of the way. B. Without the benefit of the hook, it would be exceedingly difficult to obtain an adequate colposcopic view of the lateral fornices.

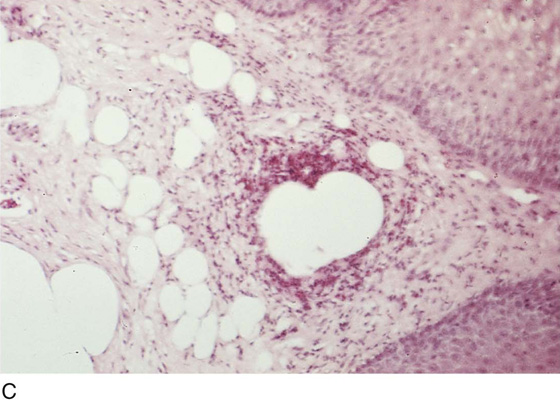

FIGURE 60–5 A. Numerous small cysts are seen in the anterior vaginal fornix. These cysts are filled with gas. B. A magnified view of part A reveals the appearance of vaginitis emphysematosa. C. Microscopic section through the vaginal wall (part A) showing air spaces beneath the epithelial pegs. D. Vaginitis emphysematosa is characterized by gas-filled spaces surrounded by multinucleated giant cells.

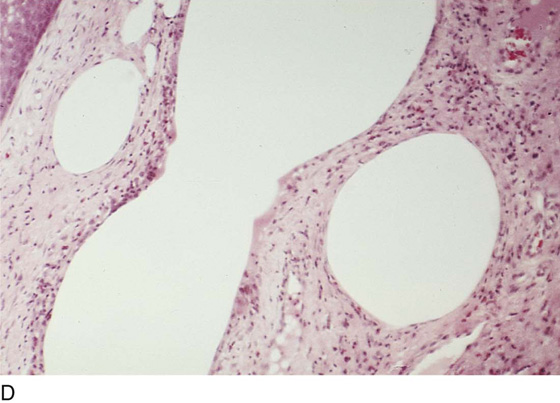

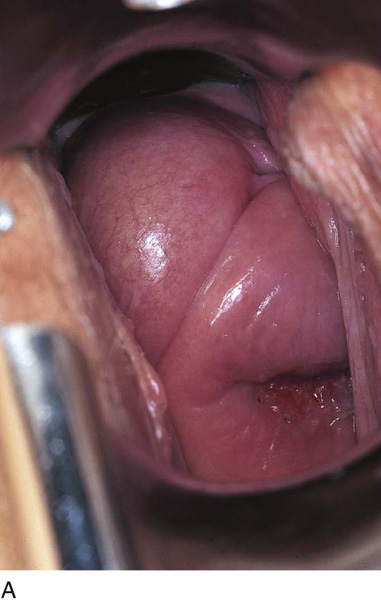

FIGURE 60–6 A. A large Gartner duct cyst is seen in the right anterolateral wall of the vagina. The cervix is displaced downward and to the left. Preoperatively, the cyst should be injected with radiopaque dye and fluoroscopically studied. An intravenous pyelogram and cystoscopy should be performed to determine the exact location of the bladder and ureter relative to the cyst. Ureteral catheterization is recommended if the cyst will be excised. B. A large cotton swab displaces the cervix posteriorly to better delineate the relationship of the Gartner duct cyst to the urinary bladder. C. Microscopic section through mesonephric duct remnant in the lateral wall of a normal vagina. Obstruction of this duct leads to a Gartner duct cyst. D. Above is the stratified squamous epithelium of the vagina. The glandular structures lying (below) in the vaginal stroma (wall) are remnants of the mesonephric duct and tubules. E. Gartner duct cysts may become quite large, as is illustrated in part A. The relationship of the cyst to the bladder and ureters must be clearly defined. This drawing illustrates several key issues. The mesonephric duct and hence any Gartner duct may extend craniad from the vagina into the broad ligament of the uterus. The ureters and the bladder base have been superimposed onto the anterior wall of the vagina. The Gartner cyst in this case illustrated impinges on both the right ureter and the right side of the bladder. F. To better define the critical relationships between the cyst and surrounding structures, a water-soluble contrast medium is injected into the cyst and fluoroscopic examination is carried out. G. Dye is also instilled into the bladder to determine the proximity of the Gartner cyst (to the right) to the bladder (to the left). H. Anterior-posterior view of the cyst relative to the bladder. I. This picture shows the relationships of the drawn-in cyst and the radiographic images.

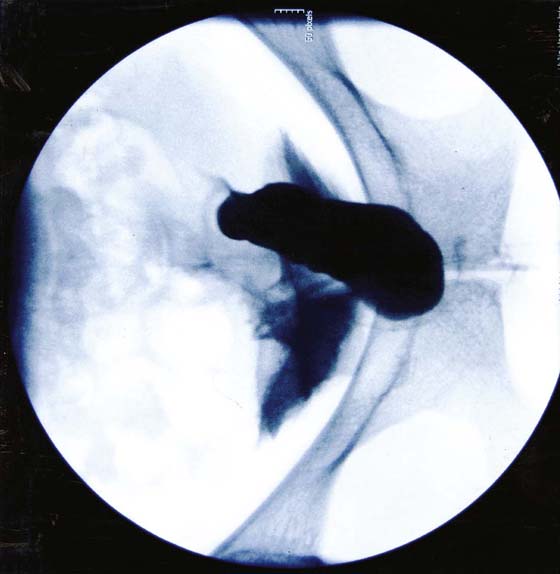

A Gartner duct cyst extending down to the lower vagina should be radiologically investigated to determine the upward extent of the cyst. Figures 60–7 through 60–10 show a cyst of the left anterior-lateral vaginal wall and its relationship to the urinary bladder.

An easy reliable technique for dealing with this type of cyst is described below.

The cyst is injected with a 1 : 100 diluted vasopressin solution (Fig. 60–11). Next, carbon dioxide (CO2) laser trace spots outline the area of the cyst that will be excised (Fig. 60–12). The excision essentially uncaps the cystic mass (Fig. 60–13). The interior of the cyst can now be viewed (Fig. 60–14). The CO2 laser beam diameter is enlarged to 2.3 mm (spot), and the interior of the cyst is systematically vaporized (Fig. 60–15). The vaporization completely denudes the thin epithelial lining of the cyst (Fig. 60–16). The opposing collapsed walls will efficiently agglutinate to one another. The fenestration site is reefed with a running lock suture of 3-0 Vicryl (Fig. 60–17). Six to 8 weeks postoperatively, the mass and the opening are gone (Fig. 60–18). The excised cyst wall is sent to pathology for confirmation.

On occasion, a Gartner duct cyst may reach a large size (i.e., greater than 5 to 10 cm) and may extend upward into the lateral aspect of the cervix. Figure 60–19 illustrates a large posterior vaginal wall Gartner duct cyst that ended up in the right lateral fornix of the vagina. In such instances, it may be advantageous to resect a significant portion or all of the cyst (Figs. 60–20 through 60–25). If a portion of the cyst remains unresected, then the interior should be vaporized to diminish the chances for recurrence (Figs. 60–26 through 60–28). At the completion of the procedure, the vaginal wall is carefully reapproximated to avoid scar formation.

FIGURE 60–7 Moderate-sized cyst attached firmly to the left anterolateral vaginal wall.

FIGURE 60–8 The cyst has been injected with radio-opaque medium. The cyst extends for 3 to 4 cm cranially.

FIGURE 60–9 The bladder has been filled with dye to determine its relationship to the cyst wall.

FIGURE 60–10 This view shows that the posterior bladder wall is safely away from the cyst wall.

FIGURE 60–11 Vasopressin, 1 : 100 dilution, is injected into the cyst wall for hemostasis.

FIGURE 60–12 Carbon dioxide (CO2) laser trace spots are placed into the cyst.

FIGURE 60–13 The cyst is uncapped by means of carbon dioxide (CO2) laser cutting or by means of scissors.

FIGURE 60–14 The interior of the cyst is now visible.

FIGURE 60–15 The laser spot size is increased to 2 to 3 mm, and vaporization of the cyst lining commences.

FIGURE 60–16 The epithelium of the cyst has been completely vaporized.

FIGURE 60–17 The margins of the uncapped portion of the cyst are closed with a 3-0 Vicryl reefing stitch.

FIGURE 60–18 The operation is completed and the field is homeostatic.

FIGURE 60–19 A large Gartner duct cyst involving the posterior vaginal wall and extending up the vagina to the level of the cervix. The cyst gradually shifted to the right and occupied the right lateral vaginal fornix.

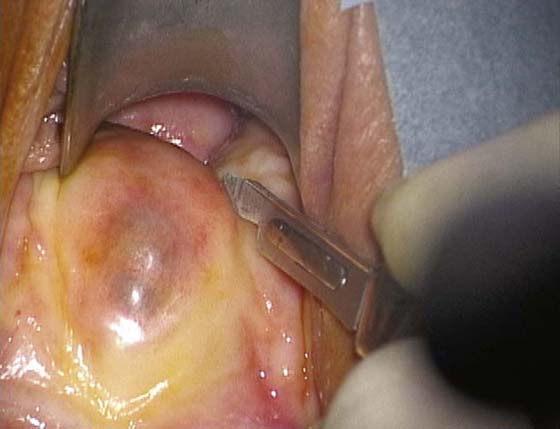

FIGURE 60–20 After injection of a 1 : 100 diluted vasopressin solution, a knife cut is made into the left posterior vaginal wall.

FIGURE 60–21 A similar incision is made on the right posterior vagina.

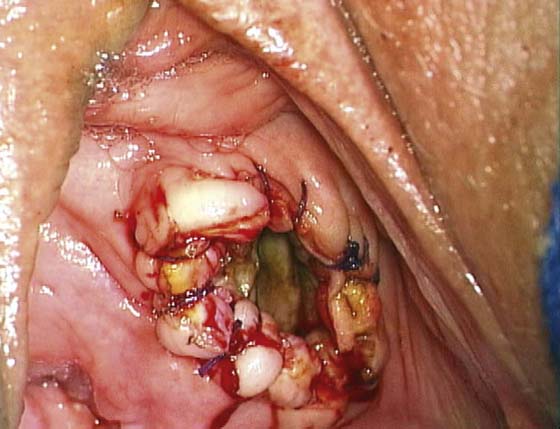

FIGURE 60–22 The cyst wall is dissected and removed, together with the adherent posterior vagina.

FIGURE 60–23 The cyst is entered and then is widely opened.

FIGURE 60–24 The interior of the cyst can be viewed, and the depth of its upward extension can be determined.

FIGURE 60–25 The posterior wall of the cyst remains. Traction is placed with the three (lower) Allis clamps. The upper two Allis clamps are attached to the remaining margin of the posterior vagina.

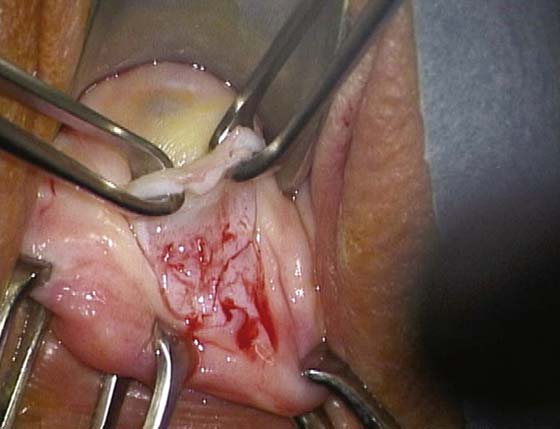

FIGURE 60–26 Laser vaporization of the posterior cyst lining the epithelium is initiated.

FIGURE 60–27 The entire posterior cyst wall has vanished (i.e., the vaporization has been completed).

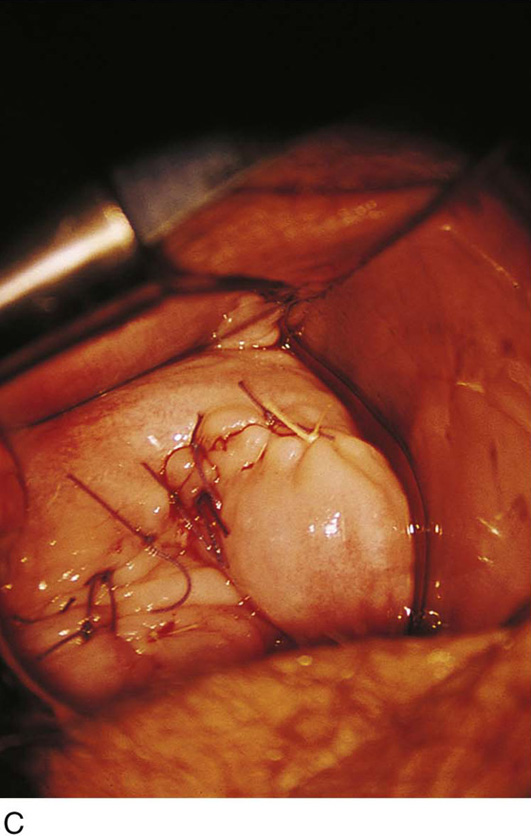

FIGURE 60–28 The posterior vaginal wall is vertically closed with 3-0 Vicryl interrupted sutures. Note that the forceps grasps the open vaginal edge as the incision swings into the right vaginal fornix. Note the cervix just cranial to the end of the forceps.

Ulcers

Ulceration may be created in the vagina through the application of toxic chemicals, tampon injury, surgery, and trauma. The ulcer is typically infected via vaginal bacteria and may expand or perpetuate as a result of the infection (Fig. 60–29A through C). The initial treatment is to perform a biopsy of the ulcer to exclude a neoplastic process; simultaneously, the ulcer should be cultured for bacteria, as well as fungi and viruses. The vagina should be irrigated two or three times daily, and a topical antibiotic (clindamycin cream) applied several times per day (Fig. 60–30A through G). Systemic antibiotics, antifungals, or antivirals are administered according to the sensitivity of the specific organism identified. If, because of a poor vascular supply, the ulcer does not regress, it should be excised. The margins should be demarcated, and the periphery injected with a 1 : 100 vasopressin solution. If the ulcer is large, a graft should be taken preoperatively. If the lesion measures less than 2 cm, it usually can be closed without constricting the vagina (Fig. 60–31A through C).

Solid Masses

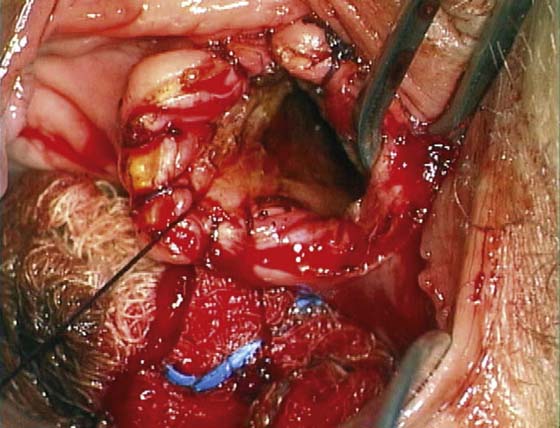

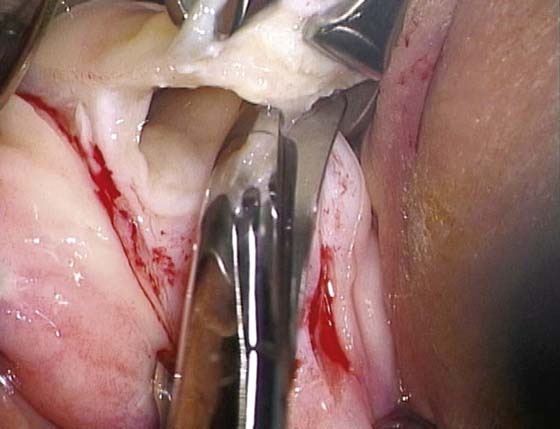

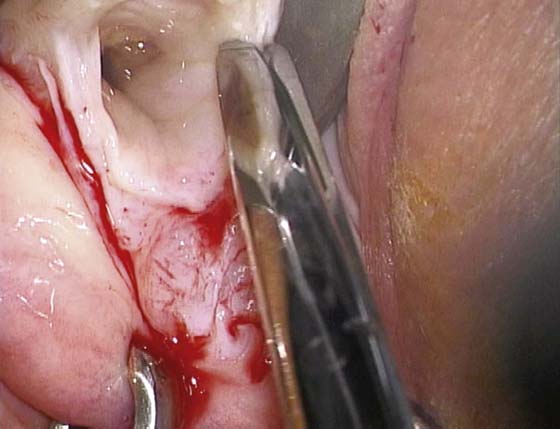

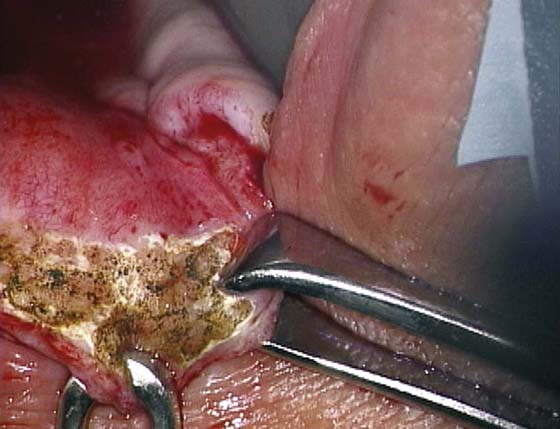

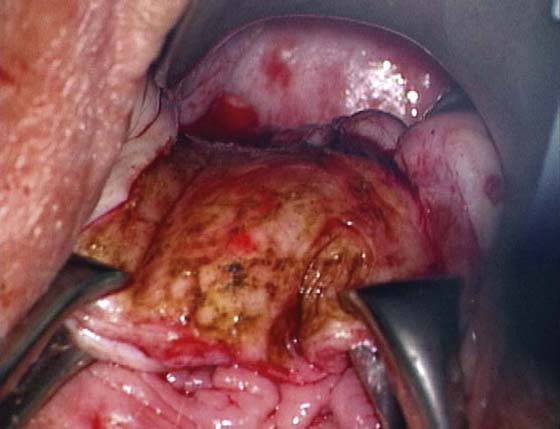

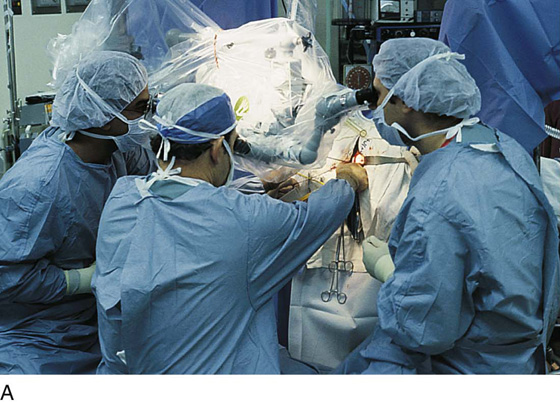

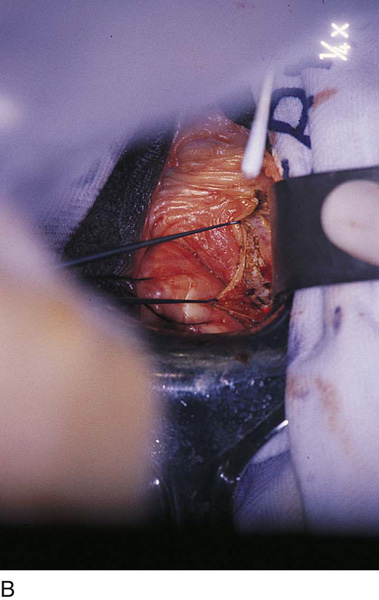

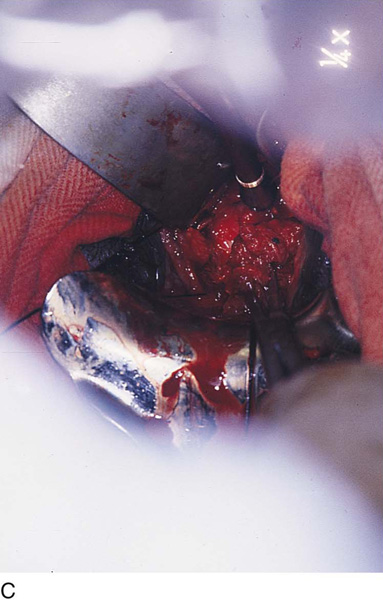

Solid masses may present in the vagina, particularly in the fornices or the vesicovaginal or rectovaginal spaces. These lesions cause pain and must be excised. Frequently, they represent infiltration of endometriosis. This type of surgery is performed by utilizing the microscope and a combination of instruments, including the CO2 laser and long tenotomy scissors. Tissue planes between the endometriosis and the normal tissue in these circumstances may be difficult to identify. Wide excision of the subepithelial mass therefore is required. Attention must be focused on neighboring structures (ureter, bladder, rectum) to avoid injuring them (Fig. 60–32A through D).

FIGURE 60–29 A. This patient complained of an uncomfortable sticking-like pain during coitus. Note the ulcer on the anterior wall of the vagina. B. The ulcer most probably was caused by a tampon. Initial treatment for this lesion is a topical antibiotic. C. This large ulcer resulted after laser vaporization of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia. It represents devitalized tissue and should be excised.

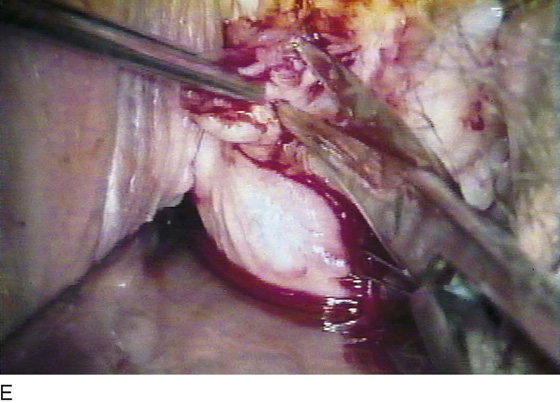

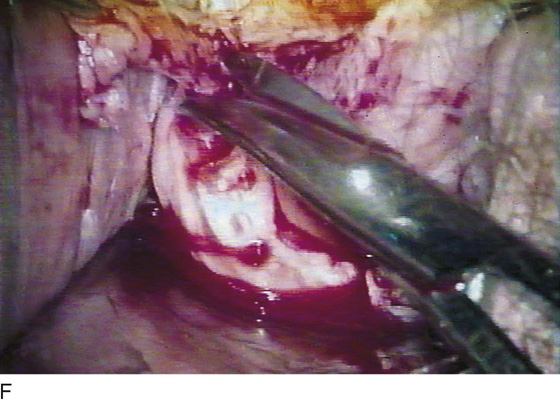

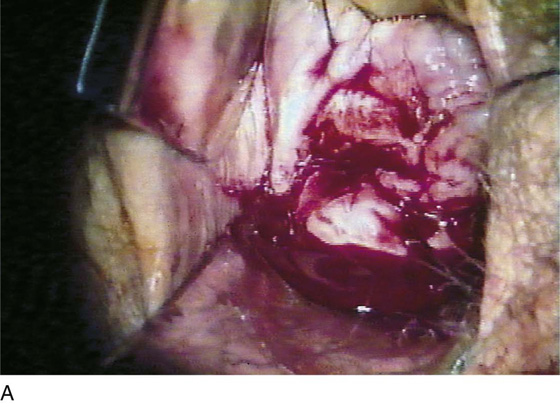

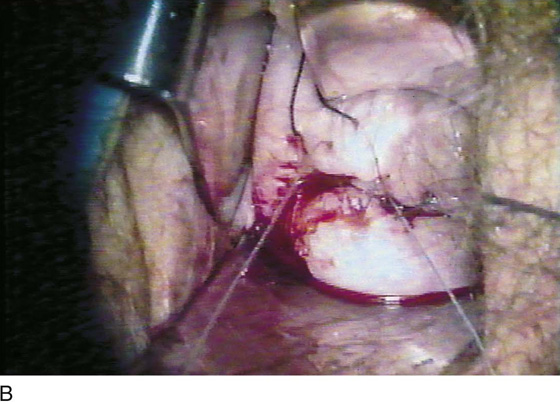

FIGURE 60–30 A. This young woman presented with a large ulcer of the right lateral vaginal wall and right fornix. This photo was taken during an office examination. B. The ulcer is fully exposed at surgery. A 1 : 100 vasopressin solution is injected with a 1½-inch, 25-gauge needle. Note the blanching beneath the ulcer. Traction sutures have been placed at the periphery of the ulcer. C. Dissection of the ulcer is initiated with Stevens scissors at the left lateral margin of the ulcer. The lesion itself occupies the right anterolateral fornix of the vagina. D. The dissection is carried above the ulcer (right anterolateral fornix) just beneath the bladder. A plane has been established, and one blade of the scissors is within the dissection plane. E. The bulk of the ulcer is held within the teeth of the forceps as the Stevens scissors separates it from the vaginal stroma. F. The ulcer is cut free from the right lateral margin of the ulcer. G. A catheter has been placed into the bladder and methylene blue dye injected. A proctoswab is placed on the ulcer bed to check for transvesical leakage of dye (bladder base disruption).

FIGURE 60–31 A. The dissected bed of the excised ulcer (Fig. 60–13A through G) is exposed in the right anterolateral vaginal fornix. B. The undermined walls of the vagina are closed over the operative site with interrupted 3-0 Vicryl sutures. C. The vaginal fornix is completely closed by primary suture. The wound is then irrigated with normal saline.

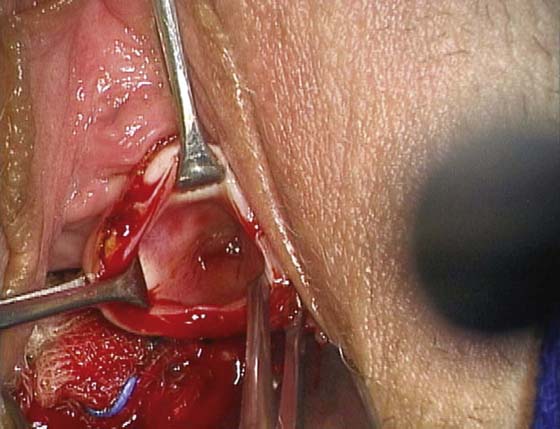

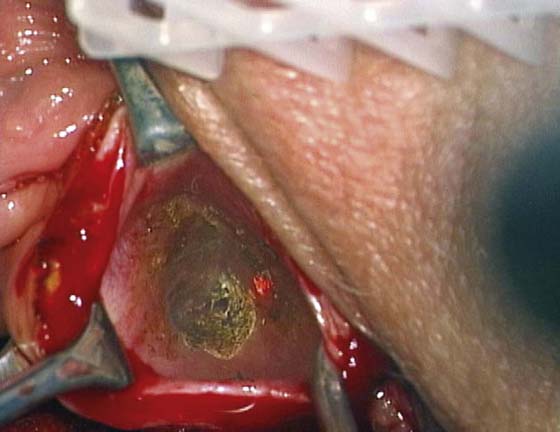

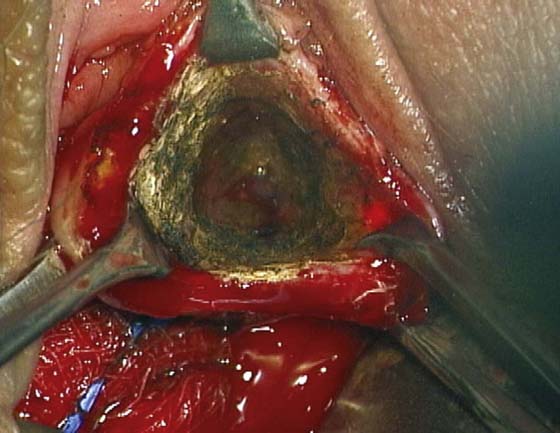

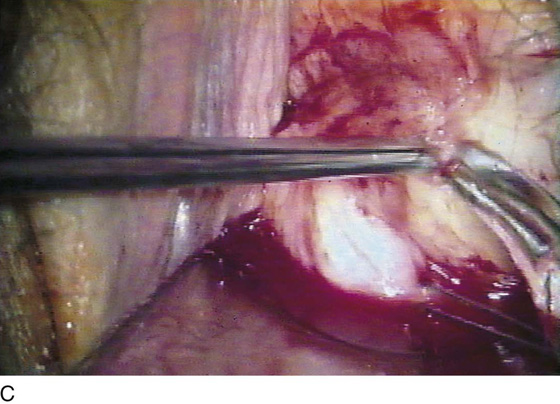

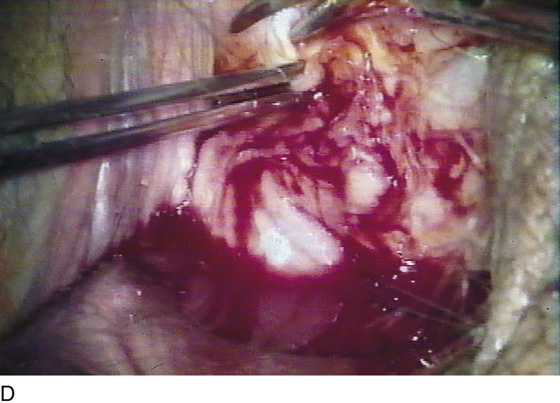

FIGURE 60–32 A. Solid masses in the vagina must be surgically removed in all cases. The dissecting microscope is the best tool for this difficult dissection. B. An incision is made into the left anterolateral fornix of the vagina over a rock-hard 3-cm painful mass. The red aiming beam of a carbon dioxide (CO2) laser is located at the lower margin of the incision. The vaginal manipulating hooks are at the upper and middle margins of the incision. C. The mass has been reached and is being dissected from the bladder base. A ureteral catheter has been placed into the left ureter. D. The excised mass has been cut to reveal endometriosis of the vaginal wall. Note the brownish siderophagic coloration of the tissue and the hemosiderin-laden fluid matter.