Benign breast disease

Introduction

Over 90% of patients presenting to a breast clinic have normal breasts or benign breast disease.1 An understanding of the aetiology, symptoms and management will ensure correct treatment and patient satisfaction. The expectation that the breast surgeon’s role is simply to diagnose or exclude breast cancer has long disappeared. Benign breast disease causes considerable morbidity and anxiety, and with increasing patient awareness and expectations, the number of such patients attending clinics is increasing. Effective treatment includes accurate diagnosis followed by adequate explanation of the condition, provision of relevant information related to the diagnosis and how it is best managed. This is a rewarding part of a breast specialist’s workload.

Congenital abnormalities

Supernumerary nipples and accessory breast tissue

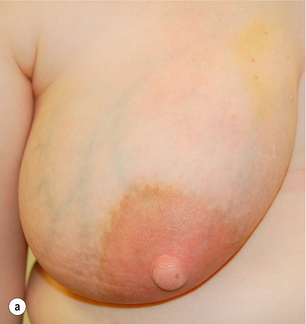

Accessory breast tissue tends to become more prominent or obvious during pregnancy (Fig. 17.1). Reassurance and an explanation of the cause of the ‘lump’ are usually all that is required. Surgical excision should be reserved for those truly symptomatic, as they are difficult to excise cosmetically and surgery is associated with significant morbidity.2 Liposuction during excision helps define the planes between the accessory breast and the fascia of the axilla. As with normal breast tissue, both benign and malignant conditions can develop within accessory breast tissue.3

Breast hypoplasia

This is failure of one or both (rarely) breasts to develop fully and can be congenital or acquired. Genetic causes include Poland’s syndrome and ulnar–mammary syndrome. Poland’s syndrome is a group of conditions associated with the absence of hypoplasia of the pectoralis major muscle, the chest wall and varying degrees of syndactyly.4 It is rare and usually only partial in nature. It is more common in men than in women. Acquired abnormalities in breast development can be caused by iatrogenic trauma or radiotherapy.

Treatment of hypoplasia and Poland’s syndrome depends on the degree of deformity. Mild asymmetry is a common problem and usually only reassurance is needed. If the asymmetry is marked, augmentation of the smaller breast with or without tissue expansion and/or reduction or augmentation of the opposite breast may be required (Fig. 17.2). Tissue expansion is often required as there are differing amounts of skin on the two breasts. A pedicled or free myocutaneous flap, with or without an implant, can be used to reconstruct any muscle defect and produce symmetry in cases of severe hypoplasia or aplasia. Fat transfer (lipofilling) has also been described as a technique to correct or aid correction of breast hypoplasia either alone or combined with a breast implant.5,6

Hypoplasia can also be associated with tubular or tuberous breasts. This deformity can affect one or both breasts and the breast shape is caused by a constricting ring at the base of the breast, limiting vertical and horizontal growth. The surgical management of this group of conditions is challenging and often unsatisfactory. Tissue expansion combined with radial incisions on the deep aspect of the breast to divide the constricting ring usually improves contour. The large nipple–areola complex may need to be reduced in size. Lipofilling is being used increasingly in such patients.6

Macromastia is the excessive development of the breasts. This tends to occur during puberty (juvenile hypertrophy) or with onset of lactation (gestational). Prepubertal breast enlargement may occur very rarely in conjunction with a hormone-secreting tumour. Juvenile hypertrophy results from excessive proliferation of ducts and stromal tissue but no lobule formation. Significant psychological and physical problems can be caused by macromastia and patients with significant breast enlargement benefit from breast reduction. This procedure is not without complications and should be performed by an appropriately trained surgeon.7

Aberrations of normal breast development and involution

Defining what represents breast disease and what is normal is not a new problem. The ANDI classification8 was developed to provide a framework to help understanding of the pathogenesis and subsequent management of benign breast disease. Most benign diseases arise from normal physiological processes and range from normality to mild abnormality (aberration) to severe abnormality (disease). The breast passes through phases related to the levels of circulating hormones and their effects on the ducts, lobule and stroma. The phases are breast development, cyclical change and involution (Table 17.1).

Table 17.1

Aberrations of normal breast development and involution

| Age (years) | Normal process | Aberration |

| < 25 | Breast development | |

| Stromal | Juvenile hypertrophy | |

| Lobular | Fibroadenoma | |

| 25–40 | Cyclical activity | Cyclical mastalgia Cyclical nodularity (diffuse or focal) |

| 35–55 | Involution | |

| Lobular | Macrocysts | |

| Stromal | Sclerosing lesions | |

| Ductal | Duct ectasia |

Fibroadenomas

A fibroadenoma is classified as an aberration of normal breast development and is made up of a combination of connective tissue and proliferatory epithelium (Fig. 17.3).9 It is not a neoplasm or benign tumour as it does not arise from a single cell. Fibroadenomas arise from the hormone-dependent terminal duct lobular unit and are influenced by hormones, e.g. increasing in size during pregnancy. The stromal element of these tumours defines their classification and behaviour. A ‘simple’ fibroadenoma contains stroma of low cellularity and regular cytology. Phyllodes tumours may or may not arise from fibroadenomas but contain stroma with much more marked cellularity and atypia. Although phyllodes tumours cannot always be differentiated on core biopsy with 100% certainty from fibroadenomas, it is usually possible to tell whether phyllodes is likely and when the lesion is a simple fibroadenoma. All discrete masses over the age of 23 should have a core biopsy – multiple passes with three samples of the lesion. Although ultrasound can usually differentiate fibroadenomas from cancers and guidelines indicate ultrasound is safe under 25, experience from medicolegal practice indicates the cut-off should be younger at 24 or below.

Simple fibroadenomas

In older women (> 23 years of age) it is clearly essential to differentiate a fibroadenoma from breast cancer by triple assessment including core biopsy. Rapid growth of a fibroadenoma is rare but can occur in either adolescence (juvenile fibroadenoma) or in the perimenopausal age group (Fig. 17.4). Tumours over 5 cm are termed ‘giant fibroadenoma’ and are seen more commonly in African countries.11 On macroscopic appearance fibroadenomas are discrete, bosselated, whitish tumours that appear to bulge when cut through. Only rarely does cancer develop within a fibroadenoma but when it does it tends to be non-invasive and lobular in nature.12

Management: The management of fibroadenomas depends on the patients’ age and preference as well as the results of triple assessment. Core biopsy (multiple cores) is now preferred to cytology to confirm the diagnosis of a fibroadenoma. In patients with lesions under 4 cm, where histology confirms the diagnosis, the patient can then be reassured and discharged. In women presenting with multiple clinical and radiological fibroadenomata, core biopsy should be undertaken of the largest lesions – either one from both breasts or two from the same breast.

Excision should be performed through a cosmetically placed incision, which includes a submammary, axillary and circumareolar incision. Another option is to remove fibroadenomas with a mammotome.13 With larger lesions (> 5 cm where histology has shown no suggestion that it could be a phyllodes tumour), it is safe to section the tumour in situ and remove it through a small incision below the breast to improve cosmetic outcome. Large lesions are best be removed cosmetically through an inframammary incision. Removal of excess skin is rarely required in young women, particularly when removing a large juvenile fibroadenoma (Fig. 17.4). In some very large lesions later revisional surgery is required but it is important to leave this for up to a year after the initial excision as skin retracts and the breast reshapes itself over this period. Recurrence of a fibroadenoma can occasionally occur but is rare and it may be due to undiagnosed adjacent lesions rather than incomplete excision.

Phyllodes tumour and sarcoma

The aetiology of phyllodes (leaf-like) tumours is unknown. They are less common than fibroadenomas (ratio of presentation 1:4014) and constitute about 2.5% of all fibroepithelial tumours. The age of onset is 15–20 years later than fibroadenomas. They can grow rapidly, sometimes producing marked distortion and cutaneous venous engorgement, which occasionally can lead to ulceration. The majority are benign in nature and feel like large fibroadenomas, and are diagnosed only following core biopsy. They are rarely fixed to skin or muscle. When cut during removal they are more brownish in colour than fibroadenomas and can have areas of necrosis within. Most diagnoses of phyllodes tumour are made before operation, on core biopsy, and the aim of surgery should be to remove the lesion with a clear macroscopic margin.

Overall, phyllodes tumours recur locally in approximately 20% of patients. Most locally recurrent tumours are histologically similar to the original lesions but occasionally benign phyllodes recur as borderline lesions. Malignant phyllodes tumours recur earlier on average than benign lesions. For benign lesions, total excision with clear margins (≥ 1 mm) is sufficient.15 For borderline and malignant lesions a wider margin is recommended and this may necessitate mastectomy with or without a myocutaneous flap for skin cover or breast reconstruction in large lesions. Regional lymph node metastases are seen rarely in malignant phyllodes tumours, with nodes being affected in approximately 5%. Metastatic spread, when it occurs, is similar in pattern to that of sarcomas. Fewer than 5% of all phyllodes tumours metastasise and approximately 25% of those classified as malignant metastasise, depending on the exact criteria used for classification. Treatment of metastatic disease is discouraging, with no sustained remissions reported from radiation, hormonal treatment or chemotherapy.

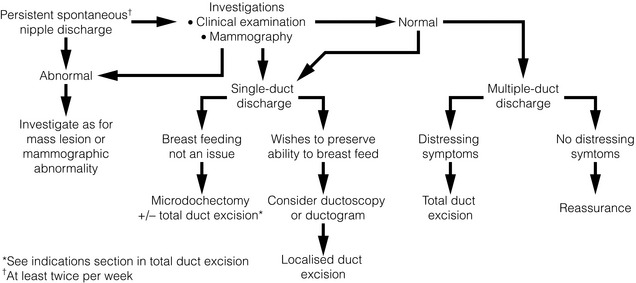

Nipple discharge

Nipple discharge accounts for 5% of referrals to a breast clinic,16 with up to 20% of these caused by in situ or malignant disease.17 The important features to assess are whether the discharge is from a single or multiple ducts, is coloured or bloodstained, is induced or spontaneous, and is affecting one or both breasts. The frequency, colour and consistency of the discharge should be noted. Blood-coloured discharge or discharge that contains significant amounts of blood on testing has been reported by some but not all authors to be more likely to arise from a cancer than coloured discharge that contains no blood on testing.18 The sensitivity and specificity of blood in the discharge is, however, not high. Persistent discharge (≥ 2 per week) is also more likely to be associated with a significant causative lesion (such as a papilloma or cancer). The aim is to differentiate between physiological causes and ductal pathology (Fig. 17.5). Discharge can be elicited by squeezing around the nipple in 20% of women19 and is often noted following mammography. If discharge is associated with a lump, then management is directed to the diagnosis of the lump.

Figure 17.5 Multiduct physiological discharge. Note the range of colours characteristic of physiological discharge.

Investigation

Assessment includes a careful breast examination to identify the presence or absence of a breast mass. Firm pressure applied around the areola can help to identify the site of any dilated duct (pressure over a dilated duct will produce the discharge); this is helpful in defining where an incision should be made for any subsequent surgery. The nipple is squeezed with firm digital pressure and if fluid is expressed, the site and character of the discharge are recorded. Testing of the discharge for haemoglobin determines whether blood is present but this is of limited value, although bloodstained discharge is more likely to be associated with malignancy. Fewer than 20% of patients who have a bloodstained discharge or who have a discharge containing moderate or large amounts of blood have an underlying malignancy. Age is said to be an important predictor of malignancy; in one series, 3% of patients younger than 40, 10% of patients between ages 40 and 60, and 32% of patients older than 60 years who presented with nipple discharge as their only symptom were found to have cancers.20 The absence of blood in nipple discharge is not an absolute indication that the discharge is unrelated to an underlying malignancy, as demonstrated in a series of 108 patients where the sensitivity of haemoccult testing was only 50%. Nipple discharge cytology is of little use due to its poor sensitivity.21,22

A number of techniques have evolved to determine the aetiology and avoid unnecessary surgery. Ductoscopy, using a microendoscope passed into the offending duct, allows direct visualisation. There are encouraging reports of its use (see Chapter 3), especially in directing duct excision at surgery23 and detecting deeper lesions that may be missed by blind central excision.24 Ductal lavage is a technique in which the duct is cannulated, irrigated with saline and the subsequent discharge examined cytologically. This technique increases cell yield by 100 times that of simple discharge cytology.25 Ductography (imaging of the ductal system) can identify intraductal lesions. Although this investigation has only a 60% sensitivity for malignancy, a filling defect or duct cut-off has a high positive predictive value for the presence of either a papilloma or a carcinoma.26,27 Ductography, however, is a painful procedure and is not widely practised.

At present, the major role of ductoscopy is as an adjunct to surgery; by using simple transillumination of the skin overlying the lesion during ductoscopy, limited duct excision is possible. The role of ductal lavage has been questioned due to large variations in its sensitivity and specificity.28,29 During ductoscopy, visualised lesions can be biopsied and in one report 38 of 46 women with biopsy-proven papillomas were observed for 2 years with no reported missed cancers.24 The role of ductoscopy in the assessment of nipple discharge is set to increase as the quality of equipment improves and it becomes more widely available. A benefit of both ductography and ductoscopy is that they allow identification of the site of any lesion in younger women, allowing localisation and excision of the causative lesion while retaining the ability to lactate (Fig. 17.6). A mammogram should be performed as part of the assessment of patients over 35 years of age with a discharge. The sensitivity in this group of patients is low, at 57%.21 Digital mammography has been shown to have a greater pick-up rate than film mammography in women under 50 or with dense breasts.30 Ultrasound can sometimes identify papillomas and malignant lesions in the ducts close to the nipple.31 Papillomas visualised on ultrasound can then be biopsied or removed using a vacuum-assisted core biopsy device.32

If no abnormality is found on clinical or mammographic examination, patients are managed according to whether the discharge is from a single duct or multiple ducts (Fig. 17.6). Any patient with spontaneous single-duct discharge should undergo surgery to determine the cause of the discharge if it is:

Aetiology

Duct ectasia: This is benign dilatation and shortening of the terminal ducts within 3 cm of the nipple. It is a common condition and increases in incidence with age. It should not be confused with periductal mastitis, which occurs in younger women and is secondary to cigarette smoking. Duct ectasia can present as nipple discharge, nipple retraction (giving a slit-like appearance) or a palpable mass. It is usually asymptomatic. The discharge is usually creamy and cheesy in nature. Bilateral multiduct green discharge is physiological and not related to duct ectasia.

Ductal papillomas: There are three main forms: a solitary-duct discrete papilloma, multiple papillomas or juvenile papillomatosis (Swiss cheese disease). Papillomas are characterised by formation of epithelial fronds that have both the luminal epithelial and the outer myoepithelial cell layers, supported by a fibrovascular stroma. The epithelial component can be subject to a spectrum of morphological changes ranging from metaplasia to hyperplasia, atypical hyperplasia and in situ carcinoma. A solitary intraductal papilloma, which occurs in a large duct (within 5 cm of the nipple), is the commonest form and is the most common aetiology of a bloody nipple discharge. They are most frequently seen in the 30–50 age group and can be palpated in one-third of patients. As papillomas have a thin stalk, they have the potential to tort and necrose. Half of women with papillomas have bloody discharge while the other half have a serous discharge.33

Ductal carcinoma in situ: Bloody nipple discharge with or without the presence of Paget’s disease constitutes one-third of all symptomatic in situ patients.34 Only rarely does an invasive cancer cause nipple discharge in the absence of a clinical mass. In most series, ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is responsible for less than 20% of unilateral single-duct nipple discharge.19 The diagnosis is often made only following surgical excision of the affected duct.

Bloody nipple discharge in pregnancy: Bilateral bloody nipple discharge detected either visibly or on testing during pregnancy or lactation is common. In 20% of women who develop nipple discharge during pregnancy, blood is evident on testing. The likely cause is hypervascularity of developing breast tissue; provided that the discharge is multiductal and/or bilateral it is benign, resolves spontaneously and requires no specific treatment.35

Nipple adenoma: Nipple adenomas present as a non-discrete, palpable growth of the papilla of the nipple (see Fig. 17.7). There may be nipple discoloration and contour change noted. Nipple adenomas tend to cause erosion of the nipple tip and commonly present as a bloody discharge from the surface of the nipple. They are benign in nature and definitive treatment is complete excision. It is caused by ductal hyperplasia of the lactiferous ducts and is seen most commonly in women of between 40 and 50 years of age.

Surgery

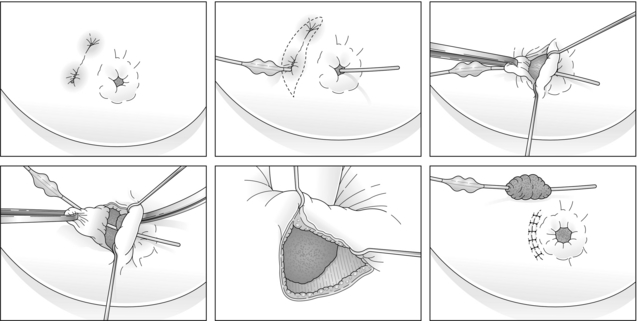

Microdochectomy: A single duct can be removed by microdochectomy. This is performed through either a radial incision or preferably a circumareolar incision. Expression of the discharge should not be performed until the patient is in theatre and fully draped in order to provide the best chance of identifying the offending duct. The discharging duct is cannulated and either a lacrimal probe placed or methylene blue injected and an incision made. The probe aids identification of the relevant duct and dissection of this from surrounding ducts/breast tissue. A length of at least 2–3 cm should be removed. The excised duct should be opened to ensure a cause for the discharge is present and the distal remnant inspected to ensure that the entire dilated duct has been excised. If the residual duct is dilated, then it should be split, opened and inspected. Microdochectomy should not damage surrounding normal ducts and allows subsequent breastfeeding. If performing a duct excision directed by ductoscopy, then having identified an abnormality in the duct, the light is used to direct the surgical excision. Once the excision has been performed, the nipple should be squeezed gently to ensure that the discharging duct has been excised.

Total duct excision or division: In women of non-childbearing age, total duct excision is an option for a single-duct discharge. Current evidence suggests that total duct excision is more likely to result in a specific diagnosis and less likely to miss underlying malignancy than microdochectomy.36 Total duct excision can also be used for multiple-duct discharge if the discharge is copious and affecting quality of life, and is often performed for periductal mastitis. The operation involves dividing all the ducts from the underside of the nipple and removing surrounding breast tissue to a depth of 2 cm behind the nipple–areola complex.37 A circumareolar incision is used. Patients should be warned that there is a small risk of nipple tip necrosis (< 1%), reduced sensation (40%) and nipple inversion associated with this operation. Patients undergoing surgery for periductal mastitis require total removal of all ducts from behind the nipple; leaving even small remnants of ducts predisposes to recurrence. Because the lesions of periductal mastitis usually contain organisms, patients should receive appropriate systemic antibiotic treatment during the operation and for 5 days after surgery. Options for antibiotic therapy include amoxicillin–clavulanate or a combination of erythromycin and metronidazole.

Mastalgia

Due to the hormonal aetiology, true breast pain is often worse before and relieved after menstruation. Exacerbating factors include the perimenopausal state (where hormone levels fluctuate) and the use of exogenous hormones (hormone replacement therapy or the oral contraceptive pill). The cause of cyclical mastalgia is unknown but studies have implicated excess production of prolactin,38 excess oestrogen,39 insufficient progesterone,40 or increased receptor sensitivity in breast tissue caused by a raised ratio of saturated fatty acids to essential fatty acids.41

Assessment

A full history and examination should be performed. The patient should be rolled and the underlying chest wall – often the site of the pain – palpated. In women over 40 years of age, mammography should be performed to exclude an occult malignancy (approximately 5% of women with breast cancer complain of pain,14 while 2.7% of women presenting with pain as their main symptom are diagnosed with breast cancer42). If a dominant lump or lumpiness is palpable, then this will dictate further management. Most breast pain, and this includes many women with cyclical breast pain, arises in the chest wall. Analgesia, a firm bra worn 24 hours a day and gentle stretching exercises such as swimming are effective treatments.

Treatment

Reassurance that the symptoms are not related to an underlying malignancy is the most effective treatment for mastalgia.43 Following this, the majority will require no further treatment.

Evening primrose oil (EPO) is not effective, as two double-blind, randomised, crossover trials comparing EPO versus placebo showed no benefit for EPO.44,45 The original work that advocated its use has never been published other than in abstract form.46 Other agents that have been shown to have some benefit include phyto-oestrogens (e.g. soya milk)47 and Agnus castus (a fruit extract).48

Reducing fat intake to less than 15% of dietary calories has been shown to improve symptoms in cyclical mastalgia.49 The patients who responded showed changes in their serum lipid profiles but the study was not blinded so placebo effects cannot be excluded and the diet is not easy to adhere to in the long term.

In severe pain, medication can be used but complications of these treatments need to be outlined to the patient. Treatment should be either tamoxifen 10 mg daily or danazol. Tamoxifen 20 mg daily was superior to placebo in a double-blind, randomised, controlled trial and pain relief was maintained in 72% of women 1 year after use.50 Tamoxifen restricted to the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle abolished pain in 85% of women. Recurrent pain at 1 year was seen in 25% and the rate of adverse effects was 21%.51 Tamoxifen 10 mg daily has fewer side-effects and is as effective as 20 mg when compared with danazol 200 mg daily.52

Tamoxifen is not licensed for use in mastalgia. Toremifene, another selective oestrogen receptor modulator, has also recently demonstrated its effectiveness in treating mastalgia. In a randomised, double-blind trial of 195 women with persistent (lasting longer than 6 months) mastalgia, they assigned patients to toremifene 30 mg daily or a matched placebo for three menstrual cycles. This demonstrated a significant benefit for toremifene but with no significant difference in adverse events between the two groups.54

A phase II trial using afimoxifene (4-hydroxytamoxifen) delivered locally to the breast as a transdermal hydroalcoholic gel daily over four cycles has shown statistically significant improvements in signs and symptoms of cyclical mastalgia across patient- and physician-rated scales, with excellent tolerability and safety. There is strong evidence that this tamoxifen metabolite is absorbed into the breast tissue but does not have the systemic effects associated with tamoxifen.55 It is not used in the UK.

Bromocriptine should not be used, due to its high rate of adverse effects (80%).56 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been reported as being of some benefit in mastalgia as part of premenstrual syndrome;57 they also have effects on fatty acid profiles.

Breast cysts

Palpable breast cysts are a common presentation to a breast clinic and affect 7% of all women.14 Small cysts have no significance except their potential to grow. Larger cysts present typically in the fifth decade and are usually multiple in nature. Cysts can be divided into apocrine and non-apocrine, depending on the consistency of the fluid found within the cyst. The only relevance of this classification is that apocrine cysts have a higher tendency to recur.58

Sclerotic/fibrotic lesions

Stromal involution can produce areas of fibrosis within the breast supporting tissues. Three different groups of such lesions are described: sclerosing adenosis, radial scars and complex sclerosing lesions (CSLs). Sclerosing adenosis can present with a palpable mass and breast pain. Mammographically, it can be associated with microcalcificaton. It differs histologically from radial scars and CSLs in the degree of excessive myoepithelial proliferation seen together with the fibrosis. Radial scars and CSLs are considered to be part of the same process but are differentiated on size (radial scar, ≤ 1 cm; CSL, > 1 cm). Radial scars and CSLs are usually asymptomatic and discovered as part of mammographic screening but can rarely present as a palpable mass. Both lesions may serve as a background for the development of atypical epithelial proliferations, including atypical hyperplasia and carcinoma in situ. Even in the absence of atypia there is some suggestion that the presence of such lesions increases the individual’s risk of malignancy.59 All these lesions, though benign in nature, are difficult to distinguish from malignancy mammographically, macroscopically and histologically. Percutaneous biopsy of these lesions with a large-gauge vacuum-assisted core needle is reliable, providing there is no associated atypia, at least 12 cores are performed and there is concordance with radiological findings.60 Malignancy cannot be excluded reliably when there is limited sampling, the presence of atypia or discordance with the radiological appearance of the lesion. Then open excision is recommended.

Non-ANDI conditions

Infection is a common problem affecting the breast,61 and can be divided into lactational, non-lactational and postsurgical. The skin overlying the breast can also become infected either primarily or secondarily because of infection developing in an existing lesion such as an epidermoid cyst or as a consequence of a generalised skin condition such as hidradenitis suppurativa.

Lactational infections

Mastitis secondary to breastfeeding occurs in approximately 5% of puerperal women and is most common during the first month or during weaning as the baby’s teeth develop. Staphylococcus aureus is the usual organism and it enters the duct system through the nipple. There is usually a history of a cracked nipple and/or problems with milk flow. Patients initially present with pain, localised erythema and swelling. If this progresses, the inflammation can affect large areas of the breast and the patient can become toxic. Promoting milk flow by continuing to breastfeed and the early use of appropriate antibiotics markedly reduces the rate of subsequent abscess formation. Infections developing within the first few weeks may result from organisms transmitted in hospital and may be resistant to commonly used antibiotics. Over half of organisms that cause breast infection produce penicillinase.62 Co-amoxiclav or flucloxacillin and erythromycin are the antibiotics of preference. Tetracycline, ciprofloxacin and chloramphenicol should not be used to treat infection in breastfeeding women because these drugs enter breast milk and may harm the child.

Non-lactational infections

Non-lactational infections are grouped into peripheral or periareolar. Those infections in the periareolar area are seen in young women and are often secondary to periductal mastitis (associated with heavy cigarette smoking).63 Substances in cigarette smoke may directly or indirectly damage the wall of subareolar ducts. Accumulation of toxic metabolites, such as lipid peroxidase, epoxides, nicotine and cotinine in the breast ducts has been demonstrated to occur in smokers within 15 minutes of a woman starting to breastfeed.64 Smoking has also been shown to inhibit growth of Gram-positive bacteria, leading to an overgrowth of Gram-negative bacteria.65 This may affect the normal bacterial flora and allow overgrowth of pathogenic aerobic and anaerobic Gram-negative bacteria, and would explain the presence of these organisms in the lesions of periductal mastitis. Microvascular changes have also been recorded and it could be that cigarettes cause some local ischaemia. The view is that the combination of damage due to toxins, microvascular damage by lipid peroxidases, and altered bacterial flora produces the clinical manifestations of periductal mastitis.

Peripheral non-lactational breast abscesses are three times more common in premenopausal women than in menopausal or postmenopausal women. The aetiology of these infections is unclear but although it was reported that these are commonly associated with diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, steroid treatment and trauma, this is untrue.66 The usual organism responsible is S. aureus. Very rarely, an infection is related to underlying comedo necrosis in DCIS. For this reason a mammogram should be performed in women over 35 years of age after resolution of the inflammation.

Postsurgical infection

Infections can present in the acute postsurgical period or after the wound has healed. There was formerly conflicting evidence of the benefit of prophylactic antibiotics during clean breast surgery, although studies have now shown a small but consistent benefit from a single perioperative dose of a broad-spectrum antibiotic such as co-amoxiclav.67 The most common organisms causing early infection include normal skin flora, S. aureus or organisms derived from the terminal ducts.68 Most surgeons give antibiotics routinely to patients having implants inserted. Patients having surgery for periductal mastitis are at increased risk of postoperative infection and all these patients should have intraoperative and postoperative antibiotics that cover the range of organisms isolated from this condition. ‘Seromas’ are frequent and can become infected following aspiration or as a result of reduced resistance to infection during chemotherapy. Radiotherapy interferes with both the blood and lymphatic flow to the breast, and its effect is to increase rates of infection in the treated area; when infection occurs, prolonged and high-dose antibiotic therapy may be required in such pateints. Redness and oedema of the breast following breast-conserving surgery are not uncommon (especially after radiotherapy). This usually occurs between 3 and 12 months following surgery. This is unresponsive to antibiotics and has an incidence of 3–5% in patients following radiotherapy for breast-conserving surgery.69 It appears to be related to obstructed lymphatic flow and responds to manual lymphatic drainage.

If an implant becomes infected, intensive antibiotic therapy is occasionally effective but usually the prosthesis has to be removed. Replacing an infected implant following thorough lavage has been reported to be effective but is rarely performed.70 It is not uncommon for implants to become infected after a minor surgical intervention (such as dental work) or during chemotherapy given as adjuvant therapy or as treatment for metastatic disease. Prophylactic antibiotics should be considered for patients with implants undergoing major dental work.

Treatment

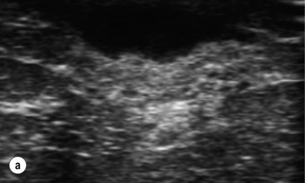

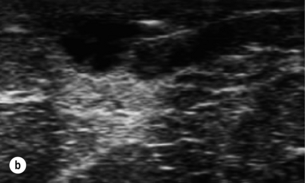

This has allowed management of breast infection to become outpatient based. Protocols validated within the Edinburgh Breast Unit have demonstrated that few if any breast abscesses require incision and drainage under general anaesthesia.75 All abscesses should be assessed by ultrasound and if pus is present the surgeon or radiologist aspirates this, usually under ultrasound guidance (Figs 17.8 and 17.9). Patients are reviewed every 2–3 days and any further collections aspirated until no further pus forms. Drainage of pus by making a small stab incision in the skin under local anaesthesia is performed in patients where the overlying skin is thinned or necrotic (Fig. 17.10). The incision to drain any breast abscess should be just large enough to allow the pus to drain (1 cm or less), which minimises later scarring. Ultrasound provides a simple method for differentiating an abscess from cellulitis, allows assessment of any loculation, which is rare, and permits complete aspiration of all pus. Experience in the Edinburgh Breast Unit of using ultrasound to assist aspiration of breast abscesses is that it is quick and simple to learn and use. Local anaesthetic (1% lignocaine with 1:200 000 adrenaline) is injected into non-inflamed skin away from the abscess and along the needle track and is then irrigated into the abscess cavity. Aspiration is then relatively painless and the local anaesthetic helps if the pus is thick by diluting the pus to allow aspiration. Periareolar non-lactational abscesses can be treated and cured by repeated aspiration. Due to the recurrent nature of periareolar infection, recurrent abscess formation is common and in such patients when all signs of acute infection have settled, which takes at least 6 weeks, careful surgical excision of any residual abscess and affected ducts is often required. A mammary duct fistula (a connection between the infected and damaged duct and the skin, usually at the edge of the areola) develops in up to one-third of patients after incision and drainage of a periareolar abscess.76 Fistulas require definitive surgical management. Options include fistulotomy, cutting down on a probe into the fistula and allowing healing by secondary intention, which is painful after surgery and produces an ugly scar, and fistula excision and primary closure. Excising a fistula is easier through a radial scar, but circumareolar incision produces the best cosmetic outcome. Complete excision of the granulation tissue lined tract (plus the affected ducts under the nipple) and primary closure requires antibiotic cover (Fig. 17.11). There is a high risk of recurrence in the presence of postoperative wound infection.77

Figure 17.8 Aspiration of abscesses under ultrasound guidance. (a) Ultrasound view of a breast abscess. (b) The needle can be seen entering the abscess on the right, allowing aspiration to be performed.

Figure 17.9 (a) Lactating abscess: skin red but normal at presentation. (b) Lactating abscess following aspiration.

Figure 17.10 Abscess of the left breast with thinned overlying skin: (a) before incision; (b) after incision and drainage through a small stab incision.

Figure 17.11 Diagrammatic illustration of the steps involved in excision of a mammary duct fistula performed through a circumareolar incision with primary wound closure under antibiotic cover.

An important aspect of the management of puerperal breast infections is the continued expression of milk, with the most efficient breast pump being the baby’s mouth. Emptying the breast increases the rate of a good outcome in infective mastitis78 and although bacteria and the antibiotic are present in the milk, this does not appear to harm the child.79 It is rarely necessary to suppress lactation but in severe unremitting or repeated infections, the prolactin antagonist cabergoline is effective at stopping milk flow.

Other infections

This is a rare condition, characterised by non- caseating granulomas and microabcesses confined to a breast lobule.80 Patients present with a firm irregular mass (which is often indistinguishable from a carcinoma) or multiple or recurrent abscesses (Fig. 17.12). The mass can be extremely tender. Young parous women are most frequently affected and there is no association with smoking. The role of organisms in the aetiology of this condition is unclear but one study did isolate corynebacteria from nine of 12 women with granulomatous lobular mastitis.81 The most common species isolated was the newly described Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii, followed by Corynebacterium amycolatum and Corynebacterium tuberculostearicum. These organisms are, however, sensitive to penicillin and tetracycline, and treatment with these antibiotics does not produce resolution of granulomatous lobular mastitis so it is unlikely that these organisms have a major role. In patients diagnosed as having granulomatous lobular mastitis on core biopsy, excision of the mass should be avoided, as it is often followed by persistent wound discharge and failure of the wound to heal. Steroids and other immunosuppressive agents have been used with varying reports of their efficacy.82 There is no convincing evidence that steroids alter the course of this condition. They do improve symptoms during administration of high doses but the condition then worsens when the dose is reduced. Reports of the benefit of injecting depot steroid are emerging. We no longer use steroids in this condition. It resolves spontaneously over a period of 6–18 months. Treatment is supportive and is aimed at treating associated infection and abscesses.

Miscellaneous benign lesions

Lipomas

Due to the fatty nature of the breast it is not surprising that lipomas are common. They tend to present in the fifth decade14 and have to be distinguished from any sinister cause. Imaging shows a radiolucent lobulated mass. Fine-needle aspiration is often reported as inadequate (C1) due to fat only being aspirated and is not recommended. A pseudolipoma is a mass that clinically appears to be a simple lipoma but is actually caused by a small cancer that produces compressed fat lobules as the suspensory ligaments of the breast shorten. Liposarcomas occur only very rarely in the breast.83 Larger or symptomatic lipomas can be excised. Some of the larger lipomas develop deep in the fascia overlying the chest wall muscles.

Diabetic mastopathy

This is a form of sclerosis occurring in premenopausal women, and occasionally men, with long-standing type I diabetes, often associated with other diabetic complications, particularly retinopathy. It can result clinically in one or more hard masses within the breast that have features making it indistinguishable clinically from malignancy, but on histology the findings are of sclerosing lymphocytic lobulitis or ‘diabetic mastopathy’. The disease probably represents an immune reaction to the abnormal accumulation of altered extracellular matrix in the breast, which is a manifestation of the effects of hyperglycaemia on connective tissue. It does not seem to predispose to breast carcinoma or lymphoma and in patients without diabetes it is not clear why some get it and others do not.84

Gynaecomastia

True gynaecomastia is caused by hyperplasia of the stromal and ductal tissue of the male breast. It is responsible for considerable embarrassment and worry and is the commonest condition affecting the male breast (Fig. 17.13). Pseudogynaecomastia gives a similar appearance but is due to excess adipose tissue with no increase in stromal or ductal tissue. Both types can present together.85 Gynaecomastia associated with Klinefelter syndrome is associated with actual lobule formation and a risk of breast cancer approaching that of the female population.

The aetiology of gynaecomastia is due to a relative hyperoestrogenism.86 This is caused by decreased androgen production, increased oestrogen production or an increase in peripheral aromatisation. In patients where no endocrine abnormality or drug is found, the cause may be a reduction in androgen receptors and/or a local increase in aromatase activity.87 Causes can be divided into physiological, pathological, drug induced (medicinal and recreational) and idiopathic. Excess intake of beer or lager can result in gynaecomastia as a consequence of the phyto-oestrogens present in these drinks. A combination of regular cannabis use and drinking large volumes of lager is particularly potent at causing gynaecomastia.

1. Physiological, or primary, gynaecomastia shows a trimodal pattern, with peaks in the neonatal period, puberty and senescence. It is often self-limiting but will occasionally require treatment.

2. Pathological causes are listed in Box 17.1.

3. Common drugs that produce gynaecomastia include: spironolactone (antiandrogen); histamine H2 antagonists, antipsychotics and methyldopa (gonadotrophin disturbance); digoxin, cannabis and griseofulvin (oestrogen receptor competitors); and anabolic steroids (Box 17.2). HIV treatment with highly active anti-retrovirals is also commonly associated.

The degree of gynaecomastia is classified using appearance (Table 17.2). A thorough history will usually elicit the underlying cause. Examination of breast, axilla, testes and abdomen should be performed.

Table 17.2

Classification of gynaecomastia

| Grade | Clinical appearance |

| I | Small but visible breast development with little redundant skin |

| IIa | Moderate breast development with no redundant skin |

| IIb | Moderate breast development with redundant skin |

| III | Marked breast development with much redundant skin |

From Simon BE, Hoffman S, Kahn S. Classification and surgical correction of gynecomastia. Plast Reconstr Surg 1973; 51:48–52.105 With permission from Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. © American Society of Plastic Surgeons.

Treatment

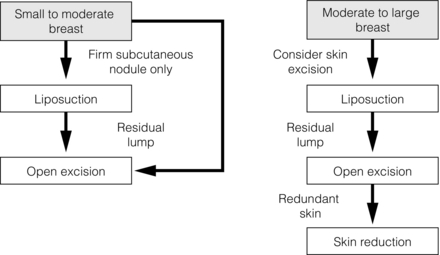

Due to the high risk of poor cosmesis associated with gynaecomastia surgery and subsequent risk of litigation, operation should only be considered after medical failure or where the gynaecomastia is large (class IIa/III). Marking the extent of the gynaecomastia prior to surgery is essential. Patients with limited gynaecomastia can have excision performed through a periareolar incision to reduce scarring. The use of lighted retractors and diathermy aids surgery. A disc of breast tissue should be left behind the nipple combined with an intact pectoral fascia and overlying fat to prevent retraction and fixation to the muscle (saucer deformity). Skin flaps are kept thick to prevent deformity and skin necrosis. Patients should be warned about nipple necrosis, sensory changes and recurrence, as well as cosmetic problems. In larger cases excess skin is removed, requiring repositioning of the nipple and even free nipple grafts.91 In young patients, excess skin often corrects itself without need for excision. The use of liposuction alone or combined with limited surgery or mammotomy improves cosmetic outcomes. Ultrasound-assisted liposuction allows treatment of more fibrous areas and increases the number of patients suitable for this technique.92 An approach to management including liposuction is outlined in Fig. 17.14.93 In those for whom surgery has produced an unsatisfactory cosmetic result, further liposuction and lipofilling can be effective in achieving a satisfactory final result.

Common complications of cosmetic breast surgery

Breast augmentation complications

Any foreign tissue placed within a body will produce a reaction or scar. The scarring around an implant produces a capsule, which contracts over time. Due to the relative inertness of silicone and the textured surface of modern implants, capsular contracture causing symptoms or significant distortion is less common than it used to be. It can be exacerbated by postoperative complications such as haematoma or a subclinical infection. Capsular contraction tends to produce pain, change in shape and hardness of the breast. A grading for capsular contraction is shown in Box 17.3. Treatment depends on severity of symptoms and patient wishes. Removal plus capsulotomy or capsulectomy for rupture is the standard treatment with or without re-augmentation.

Assessment of patients with benign breast disease

• Is a one-stop clinic the best method of diagnosing breast disease?

• Fine-needle aspiration cytology, core biopsy or both?

• Should benign breast disease become the remit of nurse specialists?

One-stop clinics

The aim of the one-stop clinic is to provide the patient with all the relevant investigations and to establish a diagnosis at the initial visit. This requires the availability of a breast radiologist to provide immediate interpretation of the examination and investigations. Even with all these available, a definitive diagnosis is not always possible.94 There are benefits in reducing anxiety in such a service (especially in the majority with normal breasts or benign disease) but this benefit is only in the short term.95 Patients like these clinics and they reduce the number of clinic visits and letters, improving administration efficiency. Although there have been concerns that immediate reporting may affect accuracy and that there may be a possible detrimental psychological aspect for those with cancer,96 these are more than offset by the benefits. It is well recognised that at the time when a patient is given bad news, little other information provided in the consultation is remembered. By concentrating on establishing and delivering a diagnosis at the first visit, it is then possible to have a more useful and constructive second visit to consider management of any cancer detected.

Fine-needle aspiration cytology, core biopsy or both?

Fine-needle aspiration cytology was the mainstay of diagnosis of symptomatic breast lumps for more than 30 years. Its introduction allowed preoperative diagnosis and avoided a large number of open excision biopsies. It has the benefit of being easy to perform, but can cause patient discomfort and has a high sensitivity and specificity (in experienced hands97). The result can be interpreted quickly, allowing rapid diagnosis. Its major disadvantage is that it does not provide architectural information on the area examined and therefore cannot differentiate in situ and invasive disease. It has been reported that it is possible to grade tumours on cytology98 and although it can provide oestrogen receptor status,99 full profiling is not possible from cytology.

There is increasing evidence that symptomatic lumps should be biopsied under ultrasound guidance.101 This ensures that the abnormality is visualised with the biopsy needle within it, improving sensitivity. Suitably trained surgeons or breast physicians, as well as radiologists, can undertake these biopsies safely.102

Future management of benign breast disease

The last few years have seen the expansion of breast physicians, nurse specialists and the formation of nurse consultants. Their roles have expanded to help with the increasing breast workload and the lack of breast specialists. There is evidence that such professionals can play an important part in symptomatic clinics, perform follow- up clinics and run symptom-specific clinics (e.g. mastalgia clinics) as long as there is specialist back-up.103,104 The future roles of these individuals are likely to expand. One note of caution: in a clinic of 30 symptomatic patients run by three or four individuals, there will be an average three cancers – that is, one per individual in the clinic. If a nurse specialist does one new patient clinic once a week, they may only see 40–45 cases of breast cancer per year. Some breast abnormalities and cancer types are rare. What is not clear is what is adequate training for such individuals. If any individual is to give a ‘consultant’ opinion in such clinics, then ideally they should have seen hundreds of breast cancers and the whole range of common and rare presentations before they make final decisions on whether patients can be discharged. This is also true for trainees who cover for consultant surgeons in such clinics. The breast surgeons of the future may be less involved in diagnosis and more active surgically.

References

1. Thrush, S., Sayer, G., Scott-Coombes, D., et al. Is the grading of referrals to a specialist breast unit appropriate or effective? Br Med J. 2002; 324:1279.

2. Down, S., Barr, L., Baildam, A.D., et al, Management of accessory breast tissue in the axilla. Br J Surg 2003; 90:1213–1214. 14515288

3. Aydogan, F., Baghaki, S., Celik, V., et al, Surgical treatment of axillary accessory breasts. Am Surg. 2010;76(3):270–272. 20349654

4. Nerakha, G.J.Gallager H.S., Leis H.P., Synderman R.K., et al, eds. The breast. Mosby: St Louis, MO, 1978:442–451.

5. Pinsolle, V., Chichery, A., Grolleau, J.L., et al, Autologous fat injection in Poland’s syndrome. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61(7):784–791. 18178141

6. Delay, E., Garson, S., Tousson, G., et al, Fat injection to the breasts: technique, results and indications based on 880 procedures over 10 years. Aesthet Surg J 2009; 29:360–376. 19825464

7. Hall-Findlay, E.J. Vertical breast reduction using the superomedial pedicle. In: Speark S.L., ed. Surgery of the breast, principles and art. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:1072–1092.

8. Hughes, L.E., Mansel, R.E., Webster, D.J., Aberrations of normal development and involution (ANDI): a new perspective on pathogenesis and nomenclature of benign breast disorders. Lancet 1987; ii:1316–1319. 2890912

9. World Health Organisation. Histological typing of breast tumours, 2nd ed. Geneva: WHO; 1981.

10. Dixon, J.M., Dobie, V., Lamb, J., et al, Assessment of the acceptability of conservative management of fibroadenoma of the breast. Br J Surg 1996; 83:264–265. 8689184

11. Hughes, L.E., Mansel, R.E., Webster, D.J.T. Benign disorders of the breast. London: Bailliére Tindall; 2001.

12. Ozzello, L., Gump, F.E., The management of patients with carcinomas in fibroadenomatous tumors of the breast. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1985; 160:99–104. 2982218

13. Sperber, F., Blank, A., Metser, U., et al, Diagnosis and treatment of breast fibroadenomas by ultrasound guided vacuum-assisted biopsy. Arch Surg 2003; 138:796–800. 12860764

14. Haagenson, C.D. Diseases of the breast, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1986.

15. Guillot, E., Couturaud, B., Reyal, F., et al, Management of phyllodes breast tumors. Breast J. 2011;17(2):129–137. 21251125

16. Dixon, J.M., Mansel, R.E., ABC of breast diseases: symptoms, assessment and guidelines for referral. Br Med J 1994; 309:722–726. 7950527

17. King, E.B., Chew, K.C., Petrakis, N.L., et al, Nipple aspiration cytology for the study of pre-cancer precursors. J Natl Cancer Inst 1983; 71:1115–1121. 6581355

18. Chen, L., Zhou, W.B., Zhao, Y., et al, Bloody nipple discharge is a predictor of breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132(1):9–14. 21947751

19. Ambrogetti, D., Berni, D., Catarzi, S., et al, The role of ductal galactography in the differential diagnosis of breast carcinoma. Radiol Med (Torino) 1996; 91:198–201. 8628930

20. Selzer, M.H., Perloff, L.J., Kelley, R.I., et al, Significance of age in patients with nipple discharge. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1970; 131:519. 5454537

21. Simmons, R., Adamovich, T., Brennan, M., et al, Nonsurgical evaluation of pathologic nipple discharge. Ann Surg Oncol 2003; 10:113–116. 12620904

22. Groves, A.M., Carr, M., Wadhera, V., et al. An audit of cytology in the evaluation of nipple discharge: a retrospective study of 10 years’ experience. Breast. 1996; 5:96.

23. Dooley, W.S., Routine operative breast endoscopy for bloody nipple discharge. Ann Surg Oncol 2002; 9:920–923. 12417516

24. Matsunaga, T., Ohta, D., Misaka, T., et al, A utility of ductography and fibreoptic ductoscopy for patients with nipple discharge. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2001; 70:103–108. 11768599

25. Shen, K.W., Wu, J., Lu, J.S., et al, Fiberoptic ductoscopy for breast cancer patients with nipple discharge. Surg Endosc 2001; 15:1340–1345. 11727147

26. King, B.L., Love, S.M., Rochman, S., et al, The Fourth International Symposium on the Intraductal Approach to Breast Cancer, Santa Barbara, California, 10–13 March 2005. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7(5):198–204. 16168138

27. Ambrogetti, D., Berni, D., Catarzi, S., et al, The role of ductal galactography in the differential diagnosis of breast carcinoma. Radiol Med (Torino) 1996; 91:198–201. 8628930

28. Khan, S.A., Baird, C., Staradub, V.L., et al, Ductal lavage and ductoscopy: the opportunities and the limitations. Clin Breast Cancer 2002; 3:185–195. 12196274

29. Van Zee, K.J., Ortega Perez, G., Minnard, E., et al, Preoperative galactography increases the diagnostic yield of major duct excision for nipple discharge. Cancer 1998; 82. 9587119

30. Pisano, E.D., Gatsonis, C., Hendrick, E., et alThe Digital Mammographic Imaging Screening Trial (DMIST) Investigators Group, Diagnostic performance of digital versus film mammography for breast-cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(17):1773–1783. 16169887

31. Cabioglu, N., Hunt, K.K., Singletary, S.E., et al, Surgical decision making and factors determining a diagnosis of breast cancer in women presenting with nipple discharge. J Am Coll Surg 2003; 196:354–364. 12648684

32. Helbich, T.H., Matzek, W., Fuchsjager, M.H., Stereotactic and ultrasound-guided breast biopsy. Eur Radiol 2004; 14:383–393. 14615903

33. Van Zee, K.J., Ortega Perez, G., Minnard, E., et al, Preoperative galactography increases the diagnostic yield of major duct excision for nipple discharge. Cancer 1998; 82:1874–1880. 9587119

34. Rosen, P.P., Cantrell, B., Mullen, D.L., et al, Juvenile papillomatosis (Swiss cheese disease) of the breast. Am J Surg Pathol 1980; 4:3–12. 7361994

35. Lafreniere, R., Bloody nipple discharge during pregnancy: a rationale for conservative treatment. J Surg Oncol 1990; 43:228–230. 2325421

36. Sharma, R., Dietz, J., Wright, H., et al, Comparative analysis of minimally invasive microductectomy versus major duct excision in patients with pathologic nipple discharge. Surgery. 2005;138(4):591–597. 16269286

37. Dixon, J.M., Kohlhardt, S.R., Dillon, P. Total duct excision. Breast. 1998; 7:216–219.

38. Peters, F., Pickardt, C.R., Zimmerman, G., et al, TSH and thyroid hormones in benign breast disease. Klin Wochenschr 1981; 59:403–407. 6793771

39. England, P.C., Skinner, L.G., Cotterell, K.M., et al, Serum oestradiol-17β in women with benign and malignant breast disease. Br J Cancer 1974; 30:571–576. 4447785

40. Sitruk-Ware, R., Sterkers, N., Mauvais-Jarvis, P., Benign breast disease. 1. Hormonal investigation. Obstet Gynecol 1979; 53:457–460. 571588

41. Gateley, C.A., Maddox, P.R., Pritchard, G.A., et al, Plasma fatty acid profiles in benign breast disorders. Br J Surg 1992; 79:407–409. 1596720

42. Mansel, R.E., ABC of breast diseases: breast pain. Br Med J 1994; 309:866–868. 7950621

43. Barros, A.C., Mottola, J., Ruiz, C.A., et al, Reassurance in the treatment of mastalgia. Breast J 1999; 5:162–165. 11348279

44. Khoo, S.K., Munro, C., Battistutta, D., Evening primrose oil and treatment of premenstrual syndrome. Med J Aust 1990; 153:189–192. 2201888

45. Blommers, J., de Lange-De Klerk, E.S., Kuik, D.J., et al, Evening primrose oil and fish oil for severe chronic mastalgia: a randomised, double blind controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002; 187:1389–1394. 12439536

46. Pashby, N.H., Mansel, R.E., Hughes, L.E., et al. A clinical trial of evening primrose oil in mastalgia. Br J Surg. 1981; 68:801–824.

47. McFayden, I.J., Chetty, U., Setchell, K.D.R., et al, A randomized double blind crossover trial of soya protein for the treatment of cyclical breast pain. Breast 2000; 9:271–276. 14732177

48. Halaska, M., Raus, K., Beles, P., et al, Treatment of cyclical mastodynia using an extract of Vitex agnus castus: results of a double blind comparison with a placebo. Cesk Gynekol 1998; 63:388–392. 9818496

49. Boyd, N.F., McGuire, V., Shannon, P., et al, Effect of a low-fat high-carbohydrate diet on symptoms of clinical mastopathy. Lancet 1988; ii:128–132. 2899188

50. Fentiman, I.S., Caleffi, M., Brame, K., et al, Double blind controlled trial of tamoxifen therapy for mastalgia. Lancet 1986; i:287–288. 2868162

51. GEMB Group Argentine. Tamoxifen therapy for cyclical mastalgia: dose randomised trial. Breast. 1997; 5:212–213.

52. Kontostolis, E., Stefanidis, K., Navrozoglou, I., et al, Comparison of tamoxifen with danazol for treatment of cyclical mastalgia. Gynecol Endocrinol 1997; 11:393–397. 9476088

53. O’Brien, P.M., Abukhalil, I.E., Randomised controlled trial of the management of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual mastalgia using luteal phase-only danazol. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999; 180:18–23. 9914571

54. Mansel, R., Goyal, A., Le Nestour, E., et alAfimoxifene (4-OHT) Breast Pain Research Group, A phase II trial of Afimoxifene (4-hydroxytamoxifen gel) for cyclical mastalgia in premenopausal women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;106(3):389–397. 17351746

55. Gong, C., Song, E., Jia, W., et al, A double-blind randomized controlled trial of toremifen therapy for mastalgia. Arch Surg. 2006;141(1):43–47. 16415410

56. Blichert-Toft, M., Anderson, A.N., Henrikson, D., et al, Treatment of mastalgia with bromocriptine: a double blind crossover study. Br Med J 1979; 1:273. 421079

57. Eriksson, E., Serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of premenstrual dysphoria. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;14(Suppl. 2):S27–S33. 10471170

58. Dixon, J.M., McDonald, C., Elton, R.A., et al, Risk of breast cancer in women with palpable breast cysts. Lancet 1999; 353:1742–1745. 10347986

59. Jacobs, T.W., Byrne, C., Colditz, G., et al, Radial scars in benign breast-biopsy specimens and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(6):430–436. 9971867

60. Brenner, R.J., Jackman, R.J., Parker, S.H., et al, Percutaneous core needle biopsy of radial scars of the breast: when is excision necessary? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179(5):1179–1184. 12388495

61. Thrush, S., Banergee, S., Sayer, G., et al. Breast sepsis: a unit’s experience. Br J Surg. 2002; 89(Suppl. 1):75–76.

62. Goodman, M.A., Benson, E.A., An evaluation of the current trends in the management of breast abscesses. Med J Aust 1970; 1:1034–1039. 4914295

63. Schafer, P., Furrer, C., Merillod, B., An association between smoking with recurrent subareolar breast abscess. Int J Epidemiol 1988; 17:810–813. 3225089

64. Petrakis, N.L., Maack, C.A., Lee, R.E., et al, Mutagenic activity of nipple aspirates of breast fluid. Cancer Res 1980; 40:188–189. 7349898

65. Ertel, A., Eng, R., Smith, S.M., The differential effect of cigarette smoke on the growth of bacteria found in humans. Chest 1991; 100:628–630. 1889244

66. Rogers, K. Breast abscess and problems with lactation. In: Smallwood J.A., Talor I., eds. Benign breast disease. London: Edward Arnold; 1990:96.

67. Gupta, R., Sinnett, D., Carpenter, R., et al, Antibiotic prophylaxis for post-operative wound infection in elective breast surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol 2000; 26:363–366. 10873356

68. Collis, N., Mirza, S., Stanley, P.R., et al, Reduction of potential contamination of breast implants by the use of ‘nipple shields’. Br J Plast Surg 1999; 52:445–447. 10673919

69. Zippel, D., Siegelmann-Danieli, N., Ayalon, S., et al, Delayed breast cellulitis following breast conservation operations. Eur J Surg Oncol 2003; 29:327–330. 12711284

70. Nahabedian, M.Y., Tsangaris, T., Momen, B., et al, Infectious complications following breast reconstruction with expanders and implants. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003; 112:467–476. 12900604

71. Hayes, R., Mitchell, M., Nunnerley, H.B., Acute inflammation of the breast: the role of breast ultrasound in diagnosis and management. Clin Radiol 1991; 44:253–256. 1959303

72. Dixon, J.M., Repeated aspiration of breast abscesses in lactating women. Br Med J 1988; 297:1517–1518. 3147056

73. O’Hara, R.J., Dexter, S.P.L., Fox, J.N., Conservative management of infective mastitis and breast abscesses after ultrasonographic assessment. Br J Surg 1996; 83:1413–1414. 8944458

74. Dixon, J.M., Outpatient treatment of non-lactational breast abscesses. Br J Surg 1992; 79:56–57. 1737278

75. Dixon J.M., ed. ABC of breast. London: BMJ Publications, 2000.

76. Bundred, N.J., Dixon, J.M., Chetty, U., et al, Mammary fistula. Br J Surg 1991; 78:1185. 1958980

77. Hanavadi, S., Pereira, G., Mansel, R.E., How mammillary fistulas should be managed. Breast J. 2005;11(4):254–256. 15982391

78. Thomsen, A.C., Espersen, T., Maigaard, S., Course and treatment of milk stasis, non-infectious inflammation of the breast and infectious mastitis in nursing women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1984; 149:492–495. 6742017

79. , Anonymous, Single dose cabergoline versus bromocriptine in inhibition of puerperal lactation: randomised, double blind, multicentre study. European Multicentre Study Group for Cabergoline in Lactation Inhibition. Br Med J 1991; 302:1367–1371. 1676318

80. Howell, J.D., Barker, F., Gazet, J.-C. Granulomatous lobular mastitis: report of further two cases and comprehensive literature review. Breast. 1994; 3:119–123.

81. Paviour, S., Musaad, S., Roberts, S., et al, Corynebacterium species isolated from patients with mastitis. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 35:1434–1440. 12439810

82. Taylor, G.B., Paviour, S.D., Musaad, S., et al, A clinicopathological review of 34 cases of inflammatory breast disease showing an association between corynebacteria infection and granulomatous mastitis. Pathology 2003; 35:109–119. 12745457

83. Blanchard, D.K., Reynolds, C.A., Grant, C.S., et al, Primary nonphylloides breast sarcomas. Am J Surg 2003; 186:359–361. 14553850

84. Kudva, Y.C., Reynolds, C.A., O’Brien, T., et al, Mastopathy and diabetes. Curr Diab Rep 2003; 3:56–59. 12643147

85. Daniels, I.R., Layer, G.T., How should gynaecomastia be managed? Aust N Z J Surg 2003; 73:213–216. 12662229

86. Carlson, H.E., Gynecomastia. N Engl J Med 1980; 303:795–799. 6997736

87. Ismail, A.A., Barth, J.H., Endocrinology of gynaecomastia. Ann Clin Biochem 2001; 38:596–607. 11732643

88. Jones, D.J., Holt, S.D., Surtees, P., et al, A comparison of danazol and placebo in the treatment of adult idiopathic gynaecomastia: results of a prospective study in 55 patients. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1990; 72:296–298. 2221763

89. Khan, H.N., Blamey, R.W., Endocrine treatment of physiological gynaecomastia. Br Med J 2003; 327:301–302. 12907471

90. Plourde, P.V., Kulin, H.E., Santner, S.J., Clomiphene in the treatment of adolescent gynecomastia. Clinical and endocrine studies. Am J Dis Child 1983; 137:1080–1082. 6637910

91. Wray, R.C., Jr., Hoopes, J.E., Davis, G.M., Correction of extreme gynaecomastia. Br J Plast Surg 1974; 27:39–41. 4817146

92. Samdal, F., Kleppe, G., Amland, P.F., et al, Surgical treatment of gynaecomastia. Five years’ experience with liposuction. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 1994; 28:123–130. 8079119

93. Fruhstorfer, B.H., Malata, C.M., A systematic approach to the surgical treatment of gynaecomastia. Br J Plast Surg 2003; 56:237–246. 12859919

94. Eltahir, A., Jibril, J.A., Squair, J., et al, The accuracy of ‘one stop’ diagnosis for 1110 patients presenting to a symptomatic breast clinic. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1999; 44:226–230. 10453144

95. Dey, P., Bundred, N., Gibbs, A., et al, Costs and benefits of a one stop clinic compared with a dedicated breast clinic: randomised controlled trial. Br Med J 2002; 324:507–510. 11872547

96. Harcourt, D., Ambler, N., Rumsey, N., et al. Evaluation of a one-stop breast clinic: a randomised controlled trial. Breast. 1998; 7:314–319.

97. Dixon, J.M., Lamb, J., Anderson, T.J., Fine needle aspiration of the breast: importance of the operator. Lancet 1983; ii:564. 6136708

98. Robinson, I.A., McKee, G., Nicholson, A., et al, Prognostic value of cytological grading of fine-needle aspirates from breast carcinomas. Lancet 1994; 343:947–949. 7909010

99. Zoppi, J.A., Rotundo, A.V., Sundblad, A.S., Correlation of immunocytochemical and immunohistochemical determination of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. Acta Cytol 2002; 46:337–340. 11917582

100. Britton, P.D. Fine needle aspiration or core biopsy? Breast. 1999; 8:1–4.

101. Hatada, T., Ishii, H., Ichii, S., et al, Diagnostic value of ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy, core needle biopsy, and evaluation of combined use in the diagnosis of breast lumps. J Am Coll Surg 2000; 190:299–303. 10703854

102. Whitehouse, P.A., Baber, Y., Brown, G., et al, The use of ultrasound by breast surgeons in outpatients: an accurate extension of clinical diagnosis. Eur J Surg Oncol 2001; 27:611–616. 11669586

103. Garvican, L., Grimsey, E., Littlejohns, P., et al, Satisfaction with clinical nurse specialists in a breast care clinic: questionnaire survey. Br Med J 1998; 316:976–977. 9550957

104. Earnshaw, J.J., Stephenson, Y., First two years of a follow-up breast clinic led by a nurse practitioner. J R Soc Med 1997; 90:258–259. 9204020

105. Simon, B.E., Hoffman, S., Kahn, S., Classification and surgical correction of gynaecomastia. Plast Reconstr Surg 1973; 51:48–52. 4687568