19 Benign and Borderline Tumors of the Lungs and Pleura

Malignant neoplasms are more common, by far, than benign tumors in the lower respiratory tract. In the United States, lung carcinoma is the leading cause of cancer-related death in both sexes, and it accounts for more than 0.7% of new malignancies each year in men.1 In Europe, the situation is even worse; for example, more than 3.0% of newly diagnosed malignant neoplasms in Germany are lung cancers.2 These data reflect the continuing use of cigarettes worldwide and the relative potency of tobacco smoke as a carcinogenic agent.

Benign Pleuropulmonary Neoplasms

Clinical Features

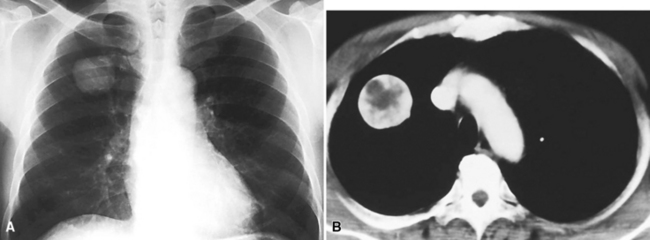

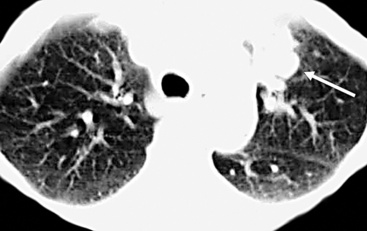

The clinical characteristics of benign tumors in the lower respiratory tract can be considered in an overview, because they are generally not specific to any particular diagnosis. Most benign intrapulmonary lesions are associated with no symptoms or signs whatsoever, and are found incidentally with screening radiographic studies. As discussed elsewhere in this book, hamartomas are often separable from other benign but truly neoplastic masses of the lung on imaging studies because of their common content of distinctive calcifications, fat densities, or both3 (Fig. 19-1). Otherwise, the radiologist is not typically able to distinguish between specific histologic entities in this context. Endotracheal and endobronchial tumors are more often related to clinical symptoms such as wheezing, hemoptysis, obstructive pneumonia, and postobstructive pulmonary hyperinflation, depending on their anatomic location.

In the past, radiologists were comfortable simply observing a pulmonary mass over time, if it had reassuring morphologic characteristics. In fact, statistical paradigms have been constructed to aid in this process.4 However, because of the unfortunate pressure of litigation involving putative “delays in diagnosis” of malignant neoplasms at various sites5—together with the modern availability of techniques such as video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery6—many more benign lesions of the lungs are excised today than in previous years.

Benign Tumors That Are Principally Tracheal and Endobronchial

Solitary Tracheobronchial Papilloma

A solitary papilloma of the tracheobronchial tree (SPTT) most often arises in adults—typically middle-aged—with a slight male predominance.7–22 Occasionally, even though only one papillomatous lesion of the lower respiratory tract may be present, it may coexist with papillary squamous proliferations of the larynx or oropharynx.

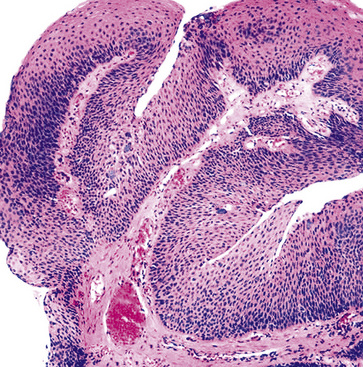

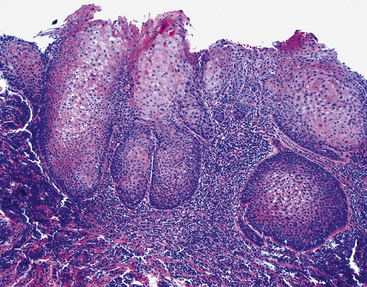

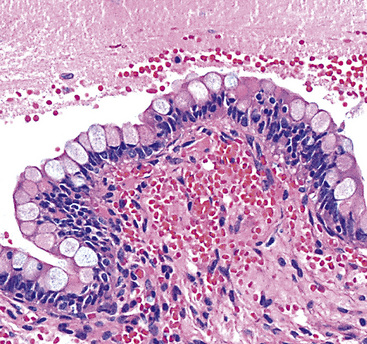

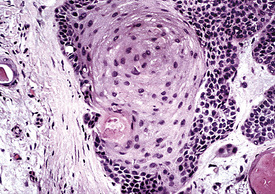

Microscopically, SPTTs are similar to viral papillomas elsewhere in the body, particularly in the genitoperineal region. They are constituted by arborizing fronds with fibrovascular cores, mantled by relatively bland squamous epithelial cells (Fig. 19-2). These often exhibit nuclear hyperchromasia and crenation, but the nuclear chromatin may be homogenized and glassy. The cytoplasm is commonly unremarkable; alternatively, it may show perinuclear clearing, eosinophilic globular inclusions, or hypergranulation with clumping of keratohyaline granules (Figs. 19-3 and 19-4). Nuclear atypia has been observed in squamous SPTT, and squamous carcinoma may develop in this setting.23,24

Another even rarer variant of SPTT is the columnar papilloma, composed of columnar epithelial cells rather than squamous elements.14 Putatively, it has no potential for malignant change.

Interestingly, the biologic associations between squamous SPTT and human papillomavirus (HPV) types are comparable to those in the genital tract. Specifically, HPV types 7 and 11 are most commonly seen in uncomplicated SPTT; in contrast, HPV types 16 and 18 are associated with dysplastic nuclear features and a higher risk of carcinomatous transformation.23,24 The presence of these viral agents can be evaluated using in situ hybridization (Fig. 19-5), the hybrid capture method, or polymerase chain reaction.23–27

In light of the usual behavior of SPTT, conservative therapeutic approaches, such as endoscopic removal, cryotherapy, or fulguration, are typically applied. Lesions in which malignancy develops must be treated in a manner appropriate for “ordinary” lung cancers (Fig. 19-6).28–31

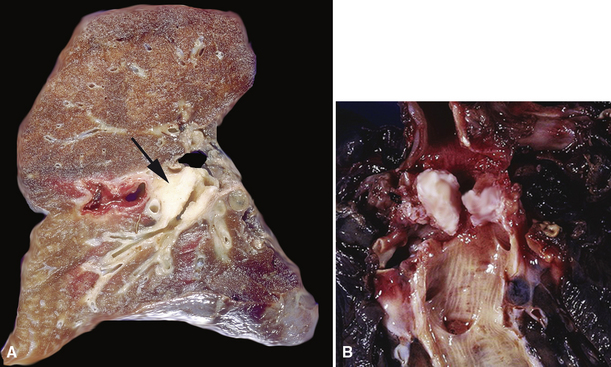

Multifocal Respiratory Tract Papillomatosis

Respiratory tract papillomatosis (RTP) is the multifocal form of viral papillomagenesis, as described earlier. Its onset is early in life because the mode of transmission is natal inhalation of virally infected genital tract secretions during vaginal delivery.32–41 Children with RTP typically have oropharyngeal or laryngeal disease initially; it may remain localized or spread to involve the lower airways as well, as seen in 5% of cases.40 In the latter instance, growth into the lung parenchyma may supervene, with the eventual appearance of cavitary lesions that can simulate carcinomas radiographically.32,41 Obstruction of the tracheal or bronchial lumina is associated with recurrent pneumonia, hemoptysis, and asthma-like symptoms. Even though RTP is often said to be “recurring,” the entire respiratory tract is at risk for infection by HPV in this disorder. Thus, it is more apropos to consider separate lesions as metachronously or synchronously independent of one another pathogenetically.

The gross and histologic features of RTP are largely the same as those of SSTP (Figs. 19-7 and 19-8). Exceptions include the multiplicity of lesions and the greater tendency for “inverting” or tissue-destructive growth of the papillomatous lesions in RTP (Fig. 19-9). The HPV profiles of RTP and SSTP are comparable, with the notable proviso that HPV-11 is overwhelmingly the most common viral type seen in RTP. Mutations of the p53 gene have been linked to malignant transformation of individual lesions in both conditions.23,24,27,41–46

It does not appear as though treatment with HPV-targeted antiviral medications (specifically, cidofovir) produced morphologic changes in persistent papillomatous lesions of the airway.47

The incidence of previous HPV integration was assessed by Clavel and colleagues25 using the hybrid capture method in a series of bronchopulmonary carcinomas. They found evidence of oncogenic HPV integration in only 2.7% of those tumors. On the other hand, Yousem and colleagues48 demonstrated similar positivity by in situ hybridization in 30% of squamous carcinomas and 17% of large cell undifferentiated carcinomas of the lung; Syrjanen28 likewise observed histologic viral changes in adjacent metaplastic bronchial mucosa in 26 of 104 squamous carcinomas (25%). Based on these data, it must be acknowledged that HPV may play a greater role in the etiology of lung carcinomas (particularly of the squamous type) than previously thought.

Bronchial Mucous Gland Adenoma

The term “bronchial adenoma” has been plagued by many misconceptions and misapplications since its introduction by Liebow in 1952.49 However, two benign neoplastic entities could still properly be called “bronchial adenomas”—mucous gland adenoma (MGA) and mixed tumor (MT; pleomorphic adenoma; discussed later).

Mucous gland adenoma is an extraordinarily rare lesion. England and Hochholzer50 noted that one series of more than 3000 pulmonary tumors included no examples of MGA,51 and only 1 MGA was represented in another report of 130 benign neoplasms of the lung seen at a large referral center.52 In the vast experience of the U.S. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, only 10 examples of MGA were found. Men and women were equally affected, and the patients ranged in age from 25 to 67 years.50,53 There is no particular predilection for anatomic location; MGAs may arise in any of the major lobar or segmental bronchi. Radiographs either show changes of postobstructive pneumonia or hyperinflation or demonstrate a discrete nodule or coin lesion that is centered on a bronchus54–66 (Fig. 19-10). Kwon and coworkers67 have noted that MGA may produce the “air meniscus sign” on computed tomogram (CT) of the airways.

Mucous gland adenomas measure between 0.5 and 1 cm in maximal dimension. They often demonstrate encapsulation, with mucoid cut surfaces; internal fibrous septations may yield a loculated appearance as well. Occasional lesions may completely occlude the bronchial lumen (Fig. 19-11).

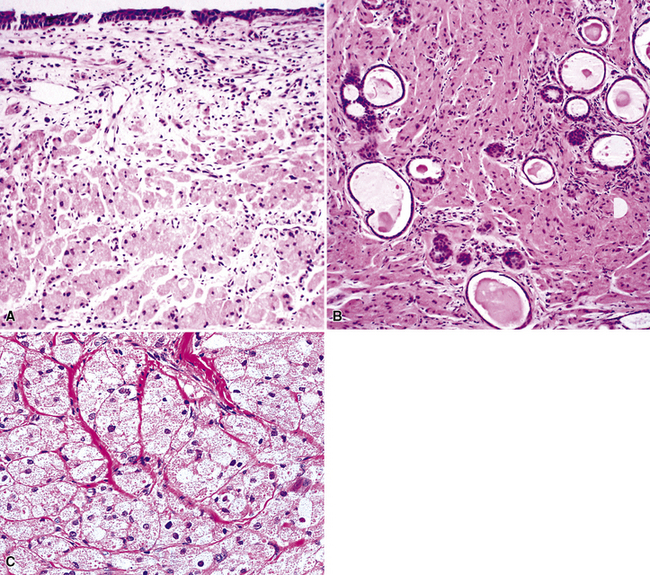

As succinctly stated by England and Hochholzer,50 “cystic change [is] the cardinal feature of MGA of the bronchus.” Microcystic arrays of cuboidal or columnar tumor cells may permeate the bronchial wall to the level of the cartilaginous plates; however, growth beyond that point is absent. Cystic contents are either overtly mucinous or more serous. Secondary formation of cholesterol clefts and dystrophic calcifications may also be seen, and squamous metaplasia in the most luminal aspect of the lesion may occur. Nuclei are generally bland, with small nucleoli, and cytoplasm may be amphophilic, oxyphilic, clear, or foamy. Mitotic figures are scarce.

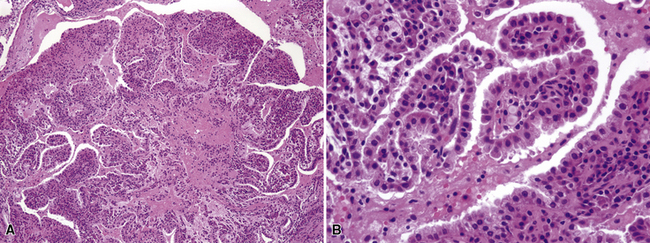

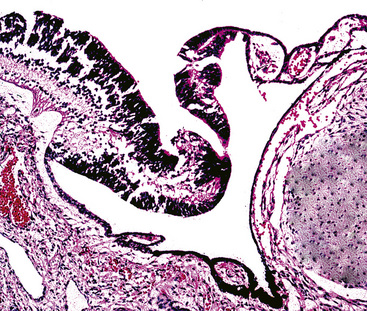

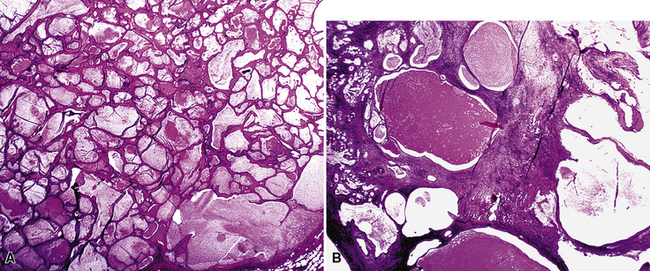

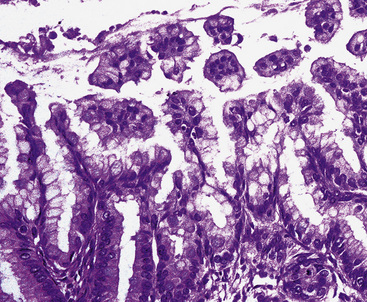

The internal substructure of MGA has been divided into two morphologic patterns: glandular-tubulocystic (Fig. 19-12) and papillocystic (Fig. 19-13). Within each of these categories, there may be a spectrum of appearances, ranging from a monotonous tubular pattern (Fig. 19-14) to a complex arborizing aggregation of papillary structures.50 Stromal sclerosis may be present.

Figure 19-12 A and B, A glandular-tubulocystic growth pattern is present in this mucous gland adenoma of the bronchus.

(Courtesy of Dr. Douglas England, Madison, WI.)

Figure 19-13 This mucous gland bronchial adenoma shows a papillocystic configuration.

(Courtesy of Dr. Douglas England, Madison, WI.)

Immunohistologic features of MGA are comparable to those of non-neoplastic bronchial glands. The constituent cells are consistently labeled for cytokeratin, epithelial membrane antigen, and blood group isoantigens, with less uniform reactivity for carcinoembryonic antigen. Stromal cells show myoepithelial features, with concurrent staining for keratin, actin, and S-100 protein.50 Squamous-type (“high molecular-weight”) keratins may be expressed in MGAs.68 This could be a diagnostic trap vis-à-vis the alternative interpretation of mucoepidermoid carcinoma (discussed later).

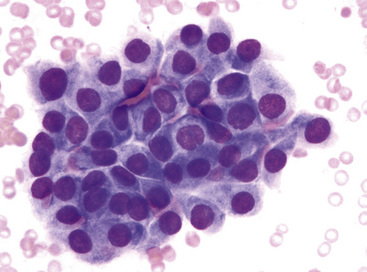

The differential diagnosis includes predominantly cystic mucoepidermoid carcinoma, MT, “sclerosing hemangioma” (pneumocytoma), and primary or metastatic mucinous (“colloid”) adenocarcinoma. Of these possibilities, the first two are the most problematic, necessitating adequate biopsies for visualization of the tumor architecture. Cytologically, MGA shows bland nests and sheets of monotonous epithelioid cells69 (Fig. 19-15). Diagnostic separation from mucoepidermoid carcinoma or MT usually is not possible using fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy or bronchial brushing specimens.

An admixture of squamous elements throughout the mass, infiltrative growth through the bronchial wall, or both would tend to argue for a diagnosis of mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Although MGA does not manifest chondromyxoid stroma or immunoreactivity for glial fibrillary acidic protein, as seen in some MTs,70 the possibility that MGA is related nosologically to monomorphic adenoma—a variant of MT—cannot be dismissed. In any event, it represents a distinctive clinicopathologic entity that is believed to deserve its own diagnostic designation.

Treatment of MGA can be conservative, with sleeve resection of the bronchus and reconstruction when clinically feasible.50,57

Salivary Gland Analog Tumors

Mixed Tumor (Pleomorphic Adenoma)

Pleomorphic adenoma—or MT—occurs predominantly in adults, with a slight preference for women.71–75 The age range is 8 to 75 years.76 The lesion may present as either a central or a peripheral mass77–79 (Fig. 19-16).

Grossly, central main stem bronchial lesions are commonly polypoid, whereas those in the periphery present as well-circumscribed tumors usually attached to bronchi (Fig. 19-17). The size of the neoplasms varies from 1 to 16 cm in greatest diameter. The cut surfaces of MTs may be chondroid and firm, or may have a soft consistency, with only focal induration.

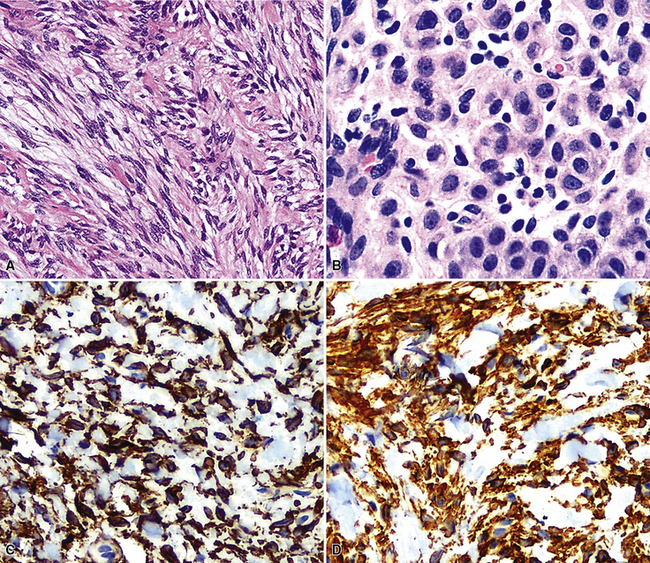

By definition, pleomorphic adenomas show at least a biphasic microscopic image; they are characteristically composed of epithelial tubules and nests that are embedded in a chondromyxoid stroma (Figs. 19-18 and 19-19). Interestingly, intrapulmonary MTs rarely show the amount of mature cartilaginous stroma present in MTs of the salivary glands. In some lesions, the predominant growth pattern may be solid myoepithelial proliferation that approximates that of “cellular” MTs in the head and neck. Those neoplasms comprise compact epithelioid cells with round or oval nuclei, which generally lack nuclear atypia, necrosis, hemorrhage, and mitotic activity (Fig. 19-20). Notably, there have been no well-documented cases of carcinoma arising from preexisting MTs of the lung, as may rarely occur in salivary glandular sites. Other variants of MT include a “myoepitheliomatous” subtype that may manifest either a spindle cell composition80 (Fig. 19-21) or a plasmacytoid constituency; a form with extensive squamous metaplasia (Fig. 19-22); a subtype in which sizable zones of the lesion demonstrate an adenoid cystic carcinoma-like cribriform architecture; and a chondroid-rich form that simulates pulmonary chondroma or chondromatous hamartoma.

Figure 19-22 Prominent squamous metaplasia is apparent in the epithelial element of this bronchial mixed tumor.

The differential diagnosis depends on whether one is dealing with a biopsy specimen or a complete resection of the tumor. In the former instance, MTs can be confused with other salivary gland-like tumors, such as adenoid cystic carcinoma, as well as with hamartoma/chondroma, squamous cell carcinoma (when squamous metaplasia is dominant), and biphasic malignancies, such as sarcomatoid carcinoma. In resection specimens, the diagnosis is typically straightforward. However, if MTs demonstrate an overwhelmingly prominent solid pattern with spindle cell (“myoepitheliomatous”) differentiation, sarcomas may also be considered. In this setting, concurrent immunoreactivity for keratin, vimentin, S-100 protein, actin or caldesmon, p63 protein, and glial fibrillary acidic protein81,82 provides the necessary evidence for a conclusive diagnosis of MT.

Mixed tumors of the lung behave in an indolent fashion. There are only anecdotal reports of metastasizing lesions of this type,83 in analogy to rare examples in the salivary glands. No particular pathologic features of such neoplasms can be used to predict this unusual adverse behavior. Complete but conservative excision is the treatment of choice.77,78

Oncocytoma

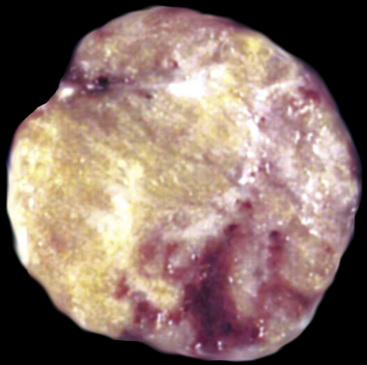

There are only a few reported cases of pulmonary oncocytoma.84–93 These tumors exhibit morphologic similarities to comparable tumors in the salivary glands, showing a brownish gross appearance (Fig. 19-23). They are composed of nests of uniformly large polygonal cells with prominently eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and bland nuclei (Figs. 19-24 and 19-25). In view of the existence of other, more common pulmonary tumors that can show oncocytic changes, it is important to properly exclude those other possibilities by adjunctive studies. Neuroendocrine tumors showing oncocytic features (oncocytic “carcinoids;” grade I neuroendocrine carcinomas) are far more common than oncocytomas and are recognizable by their immunoreactivity for chromogranin-A, synaptophysin, and CD56.94,95 Metastatic tumors from the salivary glands and kidneys also must be considered, particularly in rare cases where pulmonary oncocytomas appear to be synchronously multifocal.88 Clinical information is important in this context because the electron microscopic and immunophenotypic properties of primary and metastatic oncocytic neoplasms may be very similar (see Chapter 17).

Figure 19-24 Either solid or tubular profiles of oxyphilic polygonal cells can be seen in oncocytoma.

In general, oncocytomas in the lung and other anatomic sites are epithelial, demonstrating immunoreactivity for keratins and epithelial membrane antigen; vimentin is inconsistently present, but markers of muscular, neural, or neuroendocrine lineages are absent.88,96 Immunolabeling with antibodies to mitochondrial proteins is common,97 corresponding to the ultrastructural hallmark of these neoplasms.

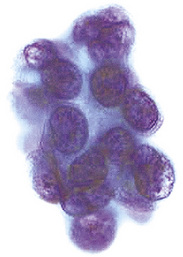

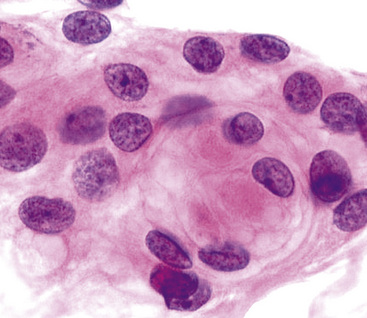

Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of oncocytic neoplasms yields a monomorphic population of large epithelioid cells with round to oval nuclei, dispersed chromatin, small nucleoli, and amphophilic to acidophilic cytoplasm. They are variably cohesive and typically show little nuclear pleomorphism.88

Because of problems with the previous definition of “pulmonary oncocytoma,” as noted earlier, meaningful comments on its behavior are difficult. However, we have seen cases that obviously invaded the lung parenchyma and had atypical morphologic features, such as nuclear pleomorphism and atypical mitoses (Fig. 19-26). Accordingly, such lesions are defensibly labeled as “malignant” oncocytomas.85

Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors

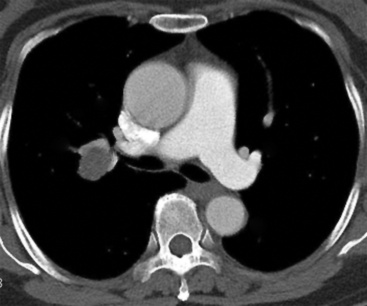

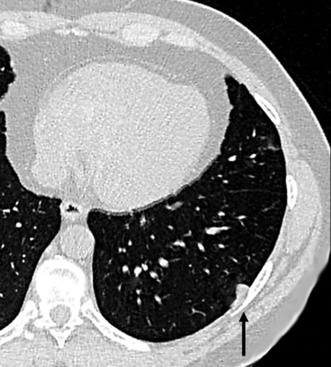

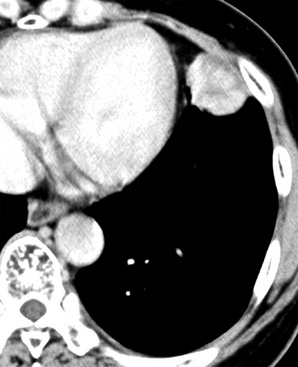

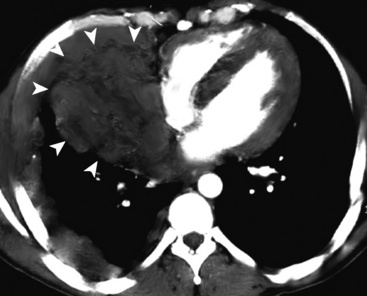

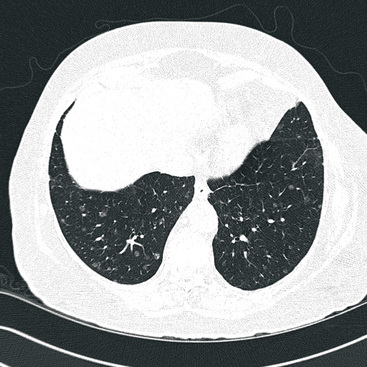

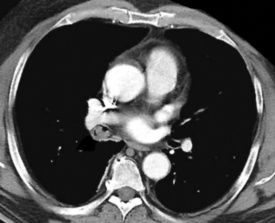

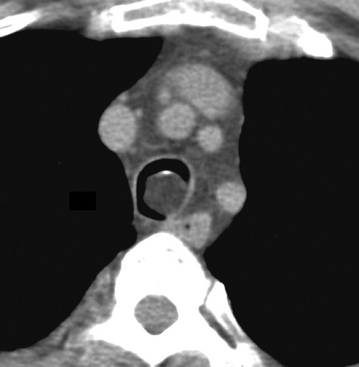

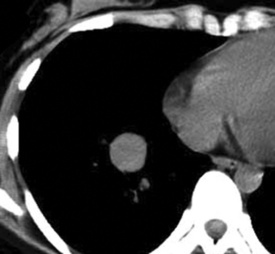

Primary neoplasms of the lung that demonstrate schwannian or perineurial differentiation are more often located in the walls of the major bronchi than in the peripheral lung.98–113 Chest radiographs show nodular or irregular masses associated with bronchi; secondary atelectasis is sometimes noted as well98 (Fig. 19-27). Some patients with primary neurogenic pulmonary tumors have neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1; von Recklinghausen’s disease), and that is true for both neurofibroma and neurilemmoma.114 Neurogenic sarcomas also arise in the lungs,115–117 but it is unclear how many have occurred in the context of NF1 in association with preexisting pulmonary neurofibromas.

Figure 19-27 A computed tomographic image of a bronchial neurilemmoma showing a mass in the lumen of the right mainstem bronchus.

Grossly, peripheral nerve sheath tumors (PNSTs) of the bronchus are well-demarcated yellow-white masses centered on the bronchial wall and often protruding into the bronchial lumen (Figs. 19-28 and 19-29). Gross foci of hemorrhage, necrosis, or cystification are absent in benign lesions of this type.

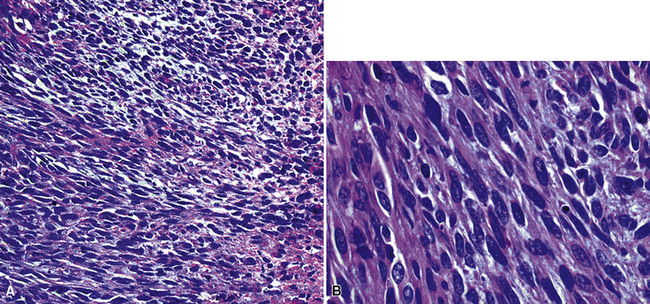

The histologic images associated with benign PNSTs are varied. Prototypical neurofibromas are “plexiform” in NF1, putatively reflecting a neoplastic attempt to recapitulate a neural plexus. Constituent cells are serpiginous, with attenuated fusiform nuclei and delicately fibrillar cytoplasm (Fig. 19-30). The supporting matrix is myxedematous or collagenized, and it may contain scattered foam cells, mast cells, and lymphocytes. Mitotic activity is typically absent. Neurilemmomas—also termed “schwannomas”—are biphasic in their classic form, with compactly cellular (“Antoni A”) areas alternating with zones of loose cellularity and myxoid change (“Antoni B” foci) (Figs. 19-31 and 19-32). Nuclei may be aligned in register in Antoni A areas, representing “Verocay bodies” (Fig. 19-33). Intralesional blood vessels have thick walls in many neurilemmomas, and a well-defined peripheral tumor capsule may be identified in some instances. Variants of neurilemmoma include “cellular” schwannoma, which manifests intersecting bundles of densely apposed, focally mitotic spindle cells in the context of an encapsulated mass111 (Fig. 19-34); “glandular” schwannoma; “ancient” schwannoma, showing scattered pleomorphic hyperchromatic nuclei in degenerative cells (Fig. 19-35); plexiform schwannoma, in which broad plexiform fascicles of tumor cells show the substructure of neurilemmoma; and melanotic psammomatous schwannoma, exhibiting microcalcifications and melanin pigmentation118 (Fig. 19-36). The last of these subtypes may be associated with myxomas of the skin, heart, and breast; the presence of cutaneous ephelides; and overactivity of the endocrine glands.

Figure 19-32 An Antoni B focus in a bronchial neurilemmoma (lower left) with a myxoid intercellular matrix.

Figure 19-34 Cellular schwannoma (neurilemmoma) demonstrating densely agglomerated spindle cells with focal mitotic activity.

Figure 19-35 “Ancient” neurilemmoma showing degenerative atypia of tumor cell nuclei with mild pleomorphism and hyperchromasia.

The immunophenotype of PNSTs features reactivity for vimentin and variable labeling for S-100 protein (Fig. 19-37), CD56, CD57, glial fibrillary acidic protein, and epithelial membrane antigen. The last of these markers is believed to represent perineurial differentiation in this context. Keratin positivity is absent, except in the glands of glandular schwannoma, and myogenous markers should be negative.

If the identification of PNST can be established in evaluations of bronchial biopsy specimens and radiographic findings support a benign diagnosis, the surgeon can undertake a conservative approach to the removal of such lesions.102,105 However, small samples of neurogenic neoplasms are notoriously unreliable in predicting the biologic potential of PNSTs, and they should not be used in isolation to govern decisions on therapy.

Granular Cell Tumors

Granular cell tumor (GCT; also known as “Abrikossoff’s tumor”119) may be seen in many anatomic locations.120 Fewer than 200 have been reported in the trachea and lungs.121–139 Patients of any age may have such lesions, and multiple tumors in the same individual have been reported.132,135,138,140,141

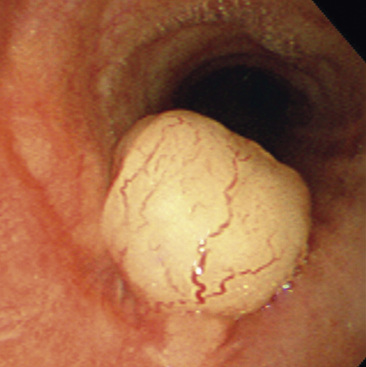

Endoscopic examination often reveals a sessile polypoid endoluminal component, with intact overlying mucosa131 (Fig. 19-38). Radiographic studies confirm that characteristic, but also demonstrate an infiltrative aspect to many GCTs that may lead to a mistaken preoperative diagnosis of malignancy.130–136 GCTs in the peripheral lung parenchyma are unusual,138 but these likewise may assume a spiculated appearance that closely simulates that of adenocarcinoma. This situation is further complicated by occasional case reports of GCTs that coexisted with malignant neoplasms.142,143

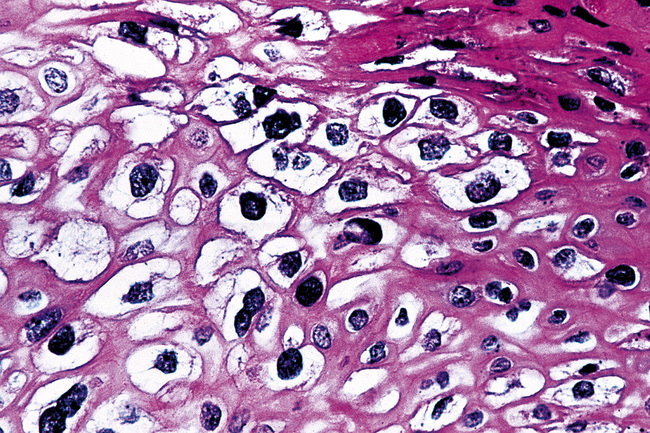

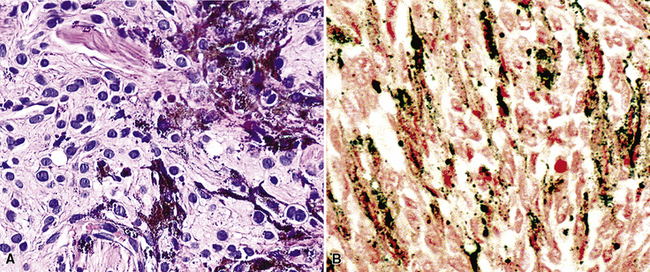

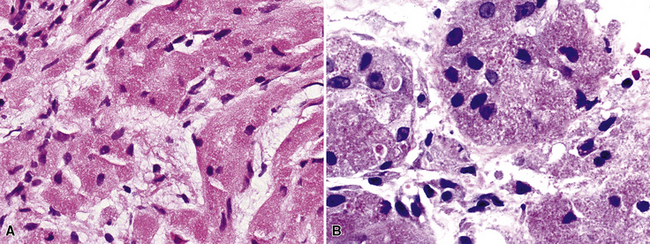

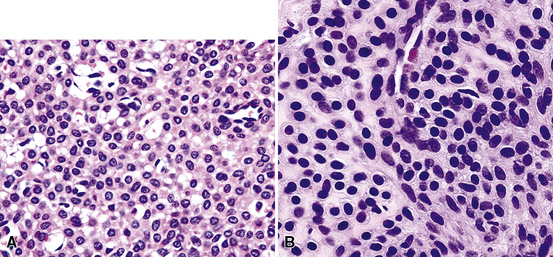

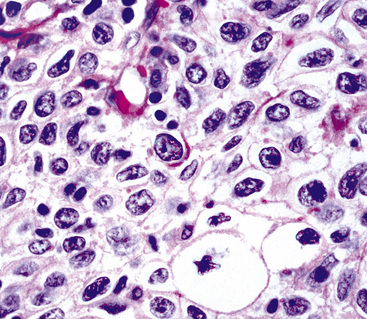

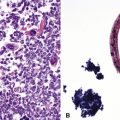

Microscopically, these tumors comprise a uniform population of polygonal or fusiform cells that contain small ovoid hyperchromatic nuclei with indistinct nucleoli (Fig. 19-39). The cytoplasm is abundant, eosinophilic or amphophilic, and coarsely granulated, often with the additional presence of rounded inclusions that superficially resemble Michaelis-Gutman bodies (Fig. 19-40). Like Michaelis-Gutman bodies, these may also have a targetoid configuration. Mitotic figures are typically scarce and physiologic; necrosis and vascular invasion are absent. The advancing border of granular cell tumors may be “pushing” or irregular and permeative. A proportion of these lesions infiltrate deeply into the bronchial wall or even through it into the adjacent parenchyma. In nonpulmonary sites, such a growth pattern has been linked to a greater risk of recurrence,144 but that correlation does not seem to apply to GCTs in the airways or lungs. The existence of primary malignant GCT of the respiratory tract has never been convincingly documented, and recurrent neoplasms are typically those that have never been completely excised.

Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of GCT yields a monotonous population of large epithelioid cells that are variably cohesive. They contain ovoid nuclei, distinct chromocenters, and abundant granular cytoplasm that is best seen in Romanowsky-stained slides (Fig. 19-41). A plasmacytoid appearance is common.145

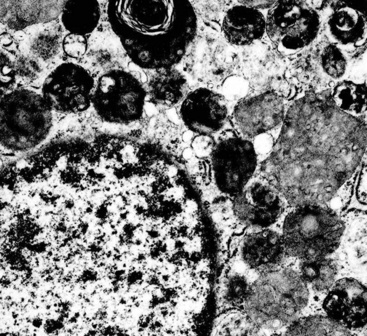

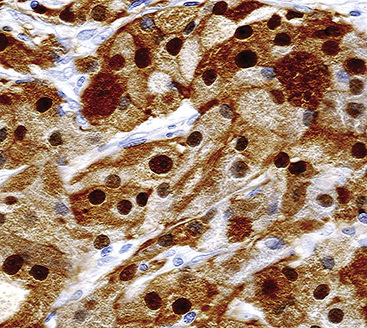

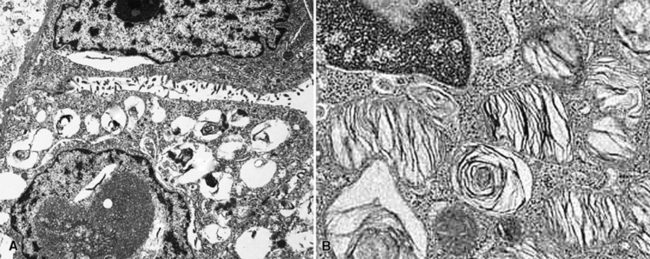

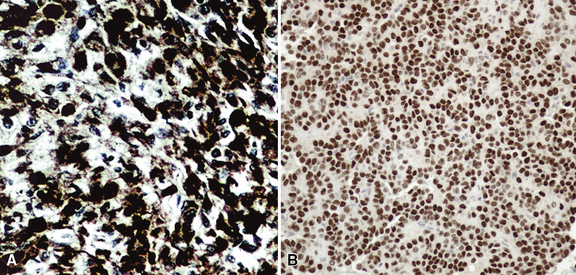

Electron microscopy of GCTs shows a distinctive multiplicity of secondary and tertiary lysosomes in the cytoplasm of the tumor cells, virtually to the exclusion of other organelles146,147 (Fig. 19-42). Immunohistologic evaluation most often reveals evidence of schwannian differentiation, with reactivity for S-100 protein, CD56, CD57, myelin basic protein, and combinations thereof, in 80% to 85% of cases147–150 (Fig. 19-43). The abundance of lysosomes is reflected by their CD68 reactivity. Recently, the presence of calretinin and alpha-inhibin has also been reported in GCT.151

An important caveat regarding the immunophenotype of this tumor type is that non-schwannian lesions containing granular cells are a heterogenous group.152 Carcinomas (both neuroendocrine and nonendocrine),153,154 smooth muscle tumors, endothelial proliferations, and neoplasms of uncommitted lineage have all been described with a granular cell phenotype. Therefore, it is important to include immunohistologic evaluations to address these possibilities in differential diagnosis, with or without ultrastructural studies. Oncocytoid granular cell grade 1 neuroendocrine carcinoma (“carcinoid”) of the lung is the most common simulator of GCT,155,156 making chromogranin-A and synaptophysin important markers in this context.

Benign Lesions Affecting Either the Airways or the Lung Parenchyma

Alveolar Adenoma

Alveolar adenoma (AA)157 is typically a solitary peripheral parenchymal nodule found incidentally in asymptomatic adult patients, with no sex predilection.158 On imaging studies, AA presents a rounded configuration and measures 1 to 6 cm in greatest dimension (Fig. 19-44).159 The surgeon is likely to report that it “shells out” from the surrounding lung tissue.160

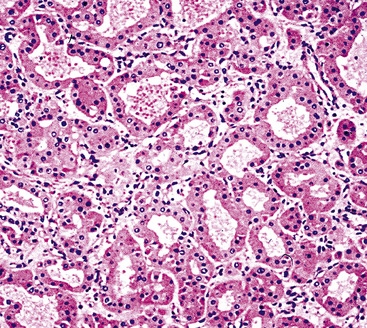

Grossly, AA is circumscribed, with a spongy gray-white multilocular cut surface. Microscopically, it comprises many cystic spaces of variable sizes, which are mantled by low-cuboidal epithelial cells (Fig. 19-45).157,158 Eosinophilic granular material is commonly present in the cyst lumina. The tissue between the cysts is represented by cytologically bland and closely apposed bluntly fusiform cells in a loose fibromyxoid matrix. Mitotic activity, nuclear pleomorphism, and necrosis are absent.161 The immunohistochemical features of AA closely parallel those of sclerosing hemangioma (“pneumocytoma”; discussed later), and it is our belief—shared by other authors as well162—that the two tumors are likely part of a neoplastic family rather than entirely distinct entities. One sees epithelial markers—including thyroid transcription factor 1—in the cuboidal cells lining tumoral microcysts, but not in the stromal elements.158,161–164 On the other hand, the latter components are reactive for vimentin, and often for CD34.158

The differential diagnosis of AA is limited. Aside from sclerosing hemangioma, which is usually larger than AA and does not have its prominently cystic substructure,162 the principal considerations are pulmonary hemangioma-lymphangioma and atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (see Chapter 16). The vascular lesions can be identified by appropriate immunohistochemical stains.165,166 Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia lacks microcysts and does not contain a mesenchymal stromal cell component.167

Even though fewer than 50 cases of AA have been reported, the behavior of this tumor has been uniformly favorable. Hence, conservative wedge excision appears to represent adequate treatment.158,160,168,169

Papillary Adenoma

Another uncommon neoplasm that is likely related to sclerosing hemangioma has been reported separately as “papillary adenoma” of the lung (PAL). It may be seen in children and adults alike, as a nondescript and asymptomatic parenchymal nodule in imaging studies.170–180 Multifocality occurs, and in one case, such multiplicity was seen in a patient with neurofibromatosis.176 Grossly, this tumor usually shows sharp circumscription from the surrounding lung tissue in most cases, with a solid tan-white cut surface (Fig. 19-46). Nonetheless, a few cases have had infiltrative characteristics.172,181,182

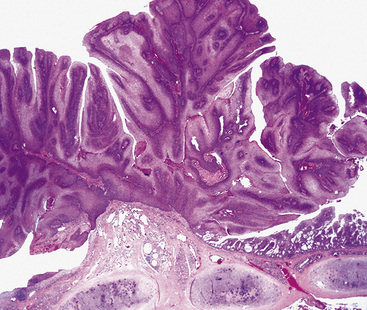

Histologically, PAL shows papillary profiles of cuboidal to low columnar, nonciliated, focally vacuolated epithelial cells that mantle well-formed fibrovascular cores (Fig. 19-47). The stroma in the latter structures may contain mixed inflammatory infiltrates, potentially including lymphocytes, mast cells, plasma cells, and eosinophils. The surrounding lung typically demonstrates a fibroblastic response to the lesion, sometimes with formation of a circumferential pseudocapsule. Mitotic activity is limited, and necrosis is absent.

Immunohistochemical studies of PAL show consistent reactivity for keratin, surfactant-related apoproteins, thyroid transcription factor 1, and napsin-A in the neoplastic cells.172,182 In addition, labeling for Clara cell antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen may be present. Ultrastructural analysis shows microvillous differentiation of the plasmalemmae and the presence of lamellar bodies in the tumor cell cytoplasm (Fig. 19-48).170–173,182

Because of the sometimes-infiltrative nature of PAL, some authors have suggested that it be considered borderline malignant.172,181,182 Nevertheless, there have been no reports of recurrence or metastasis of this lesion, and conservative surgical removal appears sufficient.

Leiomyoma

Solitary leiomyoma of the respiratory tract has been reported as an independent entity, distinct from hamartomas. These tumors are most often located in the wall of the trachea or bronchi (Fig. 19-49), with pulmonary parenchymal or pleural origins rare.183–195 Bronchoscopic and gross evaluation of central lesions shows a dome-shaped endoluminal mass, usually with a smooth mucosal surface (Figs. 19-50 and 19-51).

Figure 19-49 An endoluminal mass evident in the right bronchus intermedius proved to be a leiomyoma.

Figure 19-51 Low-power micrograph demonstrates the relationship of an endoluminal bronchial leiomyoma to the wall of the airway.

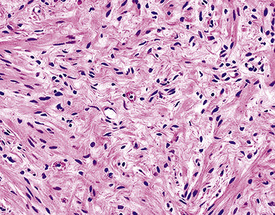

Histologically, bronchial leiomyoma is identical to benign smooth muscle tumors elsewhere in the body, comprising intertwining fascicles of spindle cells with fusiform nuclear contours, perinuclear cytoplasmic vacuolization, and finely fibrillary eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 19-52). Mitotic activity is limited, there is no infiltration of adjacent tissues, and necrosis is absent.

The fine structural features of smooth muscle proliferations in the lung include pericellular basal lamina, plasmalemmal hemidesmosomes and micropinocytotic vesicles, skeins of cytoplasmic thin filaments, and intrafilamentous dense bodies.196–198 Immunohistologically, one typically sees reactivity for muscle-specific actin, alpha-isoform (“smooth muscle”) actin, desmin, calponin, and caldesmon, with an absence of S-100 protein, CD56, CD57, and keratin.188

Solitary smooth muscle tumors are treated with simple but complete excision, if thorough clinical evaluation has excluded an extrapulmonary primary lesion of the same type. The latter proviso relates to the fact that some leiomyosarcomas (particularly in the retroperitoneum) are extremely low-grade proliferations that may produce “pseudoleiomyomatous” metastases.199

Glomus Tumor and Glomangioma

Glomus tumor and glomangioma (GTG)200–205 are most often seen in the skin and superficial soft tissue,206 but also occur with relative frequency in the alimentary tract207 and rarely the respiratory system.204 Pulmonary GTG affects adults, with an age range of 20 to 68 years204 (Fig. 19-53).

The gross features of GTG include a nodular configuration, with uniform gray-white or yellow cut surfaces and a maximum dimension of 6.5 cm, sometimes mimicking a carcinoid tumor.205

Microscopically, the lesions include compact polygonal or round cells that are closely apposed (Fig. 19-54). Nuclei are round or oval, with dispersed chromatin, scarce mitotic activity, and little if any pleomorphism. Cytoplasm is modest in amount and amphophilic or eosinophilic (Fig. 19-55). Supporting stroma consists of delicate fibrovascular septations. In lesions that lie toward the “glomangioma” pole of the spectrum, dilated vascular spaces also punctuate the lesions (Fig. 19-56), and some of these may assume a “moose antler” shape, as in the vessels seen in hemangiopericytomas. Although most are well circumscribed, a proportion of pulmonary GTGs are infiltrative.

Figure 19-54 A low-power micrograph of a pulmonary glomus tumor showing a monotonous sheet-like proliferation of cells.

One exception to this description was represented by a tumor in the series of Gaertner and associates.204 This tumor demonstrated infiltrative growth, obvious nuclear atypia with prominent nucleoli, necrosis, and brisk mitotic activity. It metastasized to several visceral sites and soft tissue, causing death in 1.3 years. Thus, it was classified as a glomangiosarcoma.

Electron microscopic examination of GTGs shows evidence of specialized smooth muscle differentiation (discussed earlier), as expected in pericytic perivascular cells.203,204 The immunophenotype of GTG includes reactivity for vimentin, actin, laminin, and collagen type IV, with an absence of keratin, neuroendocrine markers, CD31, and CD34.204

Chondroma, Myxoma, and Fibromyxoma

Several authors have posited that true chondromas and fibromyxomas of the lung208,209 exist apart from pulmonary hamartomas210–213 (see Chapter 18). In particular, Carney214 and Wick and colleagues215 have documented a constellation of masses in young women wherein multifocal cartilaginous neoplasms—apparently true chondromas—are part of a syndromic triad that includes extra-adrenal paragangliomas and gastric epithelioid stromal tumors. These are histologically different from “usual” chondroid hamartomas of the lung.216 They are frequently multiple, although they may occur singly (Fig. 19-57) in young women, more often than in elderly men (as is true for hamartomas). Chondromas lack the epithelial entrapment and “uncommitted” fibroblastic mesenchymal component that is observed in chondroid hamartomas. Instead, the interface between chondromas and the surrounding lung parenchyma is sharply demarcated (Fig. 19-58). Constituent chondrocytes are hyaline, and metaplastic osteoid is common in such lesions, more than in pulmonary chondroid hamartomas.

Solitary Pulmonary Hemangioma and “Hemangiomatosis”

True hemangiomas of the tracheobronchial tree and lung are vanishingly rare. They are usually detected in childhood.217 Discrete, variably dense and sometimes-cystic masses are present on chest radiographs (especially high-resolution CT)218 (Fig. 19-59); they may be multiple. The maximum size of individual lesions can be several centimeters. In at least one case, an intrapulmonary hemangioma was interpreted radiographically as an intrapulmonary bronchogenic cyst.217 Simple excision has been curative.

Microscopically, true hemangiomas of the airways and lungs completely replace a portion of the native tissue, with a proliferation of tubular vascular spaces lined by bland endothelial cells. A “capillary hemangioma” pattern appears to be most common, in which the caliber of the neoplastic vessels approximates that of normal small venules or capillaries (Fig. 19-60). It is implicit in this diagnosis that no other tumoral elements be identified; this is an important caveat because several other neoplasms in the lung—including some carcinomas—may contain blood lakes or pseudovascular foci that resemble the image of vascular proliferations.219

Another salient differential diagnostic consideration is “pulmonary hemangiomatosis” (see Chapter 11). That is a condition in which capillary-sized blood vessels proliferate throughout the pre-existing pulmonary parenchyma and stroma, including the alveolar septa, interlobular and interlobar septa, bronchial and bronchiolar walls, intrapulmonary vasa vasorum, and pleural surfaces.220,221 In reality, it is probably not a neoplastic process at all, but rather a malformative or reactive proliferation. For example, some cases of pulmonary hemangiomatosis have been associated with longstanding passive congestion of the lungs, as seen in left-sided heart failure.221

Lipoma and Lipoblastoma

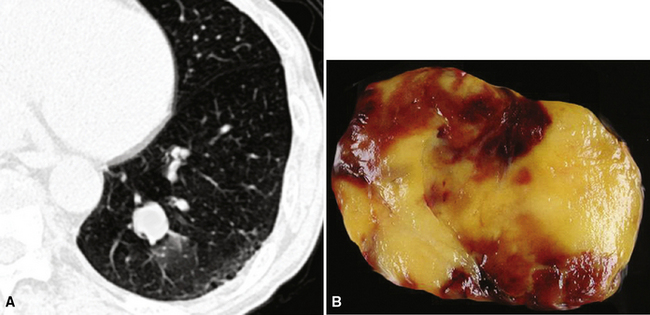

Separating examples of lipoma of the trachea and major bronchi and lung parenchyma (LTMB)222–235 from adipocytic predominant hamartomas may be difficult, and pathologic criteria for doing so are arbitrary.228 Patients with LTMB are adults, usually in the fifth or sixth decade of life.225,229 Endoscopic examination shows a variably polypoid submucosal nodule in one of the first three subdivisions of the tracheobronchial tree; radiographs demonstrate secondary atelectasis, obstructive pneumonia, or a mass in 80% of cases, but the remainder have no radiologic abnormalities on plain films.223 CTs are more sensitive in revealing the presence of lesions in airway lumina227 (Figs. 19-61 and 19-62). Current treatment recommendations are for conservative endoscopic resection after a transbronchial biopsy has established the adipocytic nature of the lesion.

Figure 19-61 This computed tomogram demonstrates an endoluminal tracheal mass that proved to be a lipoma.

Figure 19-62 This resection specimen of the lesion shown in Figure 19-61 shows uniform yellow tissue with internal lobulation.

Intrapulmonary lipomas are often subpleural (Fig. 19-63) and may even protrude into the pleural space. They are typically detected incidentally on chest radiographs. CT shows that lipomas of the lung have a density approximating that of pleural adipose tissue.227 Occasional lesions of this type have been found coincidentally in patients with pulmonary carcinomas.224 If the lipomas are multiple, small, and subpleural, they may also imitate metastatic lesions.234,235

Figure 19-63 A peripheral intrapulmonary lipoma, represented by a large globular tan-yellow lesion beneath the pleural surface.

Lipoblastoma, a neoplasm of young children236 may affect the pleura and chest wall, but only anecdotal reports exist of intrapulmonary lipoblastomas.237,238 They may be extremely large, filling almost an entire hemithorax.237 Excision is curative in the few cases with meaningful follow-up.

Liposarcoma is the rarest of primary pulmonary adipocytic neoplasms, and it has usually presented as a large single peripheral mass.239,240 Liposarcoma-like components can be seen as part of sarcomatoid carcinomas,241 and the latter lesions are far more common than primary liposarcomas of the lung.

The principal gross feature of intrapulmonary adipocytic tumors is a yellow, globular, relatively soft mass in the parenchyma (see Fig. 19-63). Internal fibrous septation may be apparent, as may a circumferential capsule or small foci of intralesional sclerosis. There is no necrosis or hemorrhage.

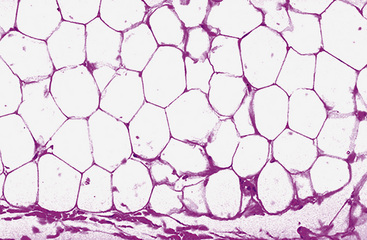

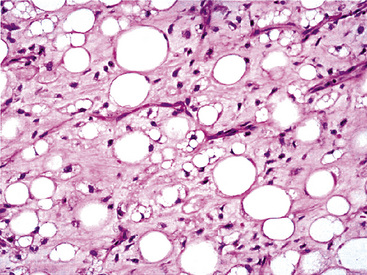

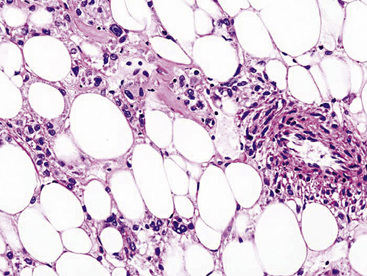

Microscopically, one sees sheets of fully mature adipocytes in ordinary lipomas (Fig. 19-64), supported by delicate fibrovascular stroma. Atypical intrapulmonary lipomas, showing scattered multinucleated “floret” cells, have been rarely reported231; however, this does not seem to have any bearing on prognosis. Lipoblastomas have a more lobulated substructure, with an admixture of uncommitted fibromyxoid tissue among mature fat cells236,242 (Fig. 19-65). True lipoblasts may be apparent as well, rare mitotic figures may be evident, and the supporting stromal tissue contains a delicately arborizing capillary network (Fig. 19-66). Therefore, the overall image of lipoblastoma may be quite similar to that of myxoid liposarcoma, and the mutually exclusive occurrence of those tumors in different age groups—with liposarcomas being seen in adults—is important to their proper identification.

Liposarcoma in the lung may assume any of the recognized morphotypes of that tumor (e.g., lipoma-like, sclerosing, myxoid, round cell, pleomorphic, and “dedifferentiated”).239,240 Those variants are recapitulated in metastatic intrapulmonary liposarcomas from primary soft tissue sites.243

Karyotypic analysis using fluorescent in situ hybridization may be useful in the differential diagnosis. Abnormalities in chromosome 8q are most common in lipoblastomas,242 whereas myxoid liposarcoma demonstrates a reproducible t(12;16) chromosomal translocation.244 Parenthetically, cytogenetic profiles are somewhat less helpful in the distinction between lipomas of the lung and lipomatous hamartomas, both of which may show abnormalities in chromosome 12.232,245 However, exchanges of material between chromosomes 6 and 14 are also potentially observed in hamartomas but not lipomas.246

Immunohistology of fatty tumors of the lungs shows consistent reactivity for S-100 protein in the adipocytic elements as well as “high-mobility-group” proteins.245 Lipoblastoma may also show positivity for factor XIIIa in its stellate and fusiform cells.242

Angiomyolipoma

In recent years, it has become apparent that a family of neoplasms—which may arise in the kidney, pancreas, alimentary system, liver, soft tissue, or respiratory tract—demonstrates differentiation toward a unique cell type that has both myogenous and melanocytic features.247–250 These tumors have been variously called “angiomyolipomas,” “perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms” (PEComas), and “myomelanocytomas.”247–251 If a typical morphologic appearance, including smooth muscle, fat, and vascular proliferation, is observed, the first of these terms is still preferred; a few lesions with such characteristics have been reported in the lung.252–257 Another member of this nosologic group—the pulmonary clear cell or “sugar tumor”—is discussed later. All of these proliferations potentially share immunoreactivity with the melanocyte-related antibody human melanin black (HMB)-45, as well as anti-actins.248 Other immunohistochemical markers of melanocytic and smooth muscle differentiation—such as antibodies to S-100 protein, tyrosinase, HMB-50, melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1), caldesmon, calponin, and desmin—may also label them.249

A proportion of patients with angiomyolipomas, regardless of anatomic location, will have phakomatosis tuberous sclerosis (Bourneville syndrome). It classically includes nodular periventricular glial proliferations and subependymal giant cell astrocytomas in the brain; cutaneous connective tissue nevi; often-multifocal renal angiomyolipomas; and pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis, with or without multifocal micronodular pneumocytic hyperplasia (see Chapter 7).253,258–260

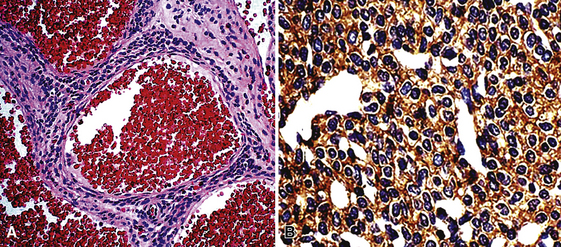

Microscopically, pulmonary angiomyolipoma is identical to its better-known renal counterpart. Prototypically, it manifests a concatenation of mature fat, variably sized and haphazardly arranged blood vessels with muscular walls, and nests or skeins of fusiform or epithelioid smooth muscle elements (Fig. 19-67). Either the fat or the smooth muscle may dominate the histologic picture and cause diagnostic confusion with either pure adipocytic neoplasms or sarcomas, respectively. Nuclear atypia has been seen in the smooth muscle elements of angiomyolipomas in extrapulmonary sites, and rare cases outside the lung have even shown overtly malignant transformation with necrosis and atypical mitotic activity.261 Those attributes have not been seen in pulmonary lesions of this type.

Electron microscopic analysis of angiomyolipoma demonstrates findings that recall the characteristics of smooth muscle cells, including pericellular basal lamina and plasmalemma-associated pinocytotic vesicles.252 Cytoplasmic bundles of thin filaments have not been found. Approximately 50% of such neoplasms show cytoplasmic premelanosomes.249

The principal immunohistologic findings in angiomyolipomas have been described earlier. Adachi and coworkers262 have reported immunoreactivity for CD1a in PEComas, including angiomyolipoma, but we have been unable to reproduce this finding.

In its “classic” form, angiomyolipoma has no realistic differential diagnostic alternatives. Nevertheless, its morphologic variants may be difficult to distinguish from metastatic melanomas, carcinomas, or sarcomas in the lung. Before an unqualified diagnosis of a pure pulmonary smooth muscle tumor or melanoma is made, additional immunocytochemical evaluation with HMB-45 (Fig. 19-68) and anti-actins is probably a prudent step.

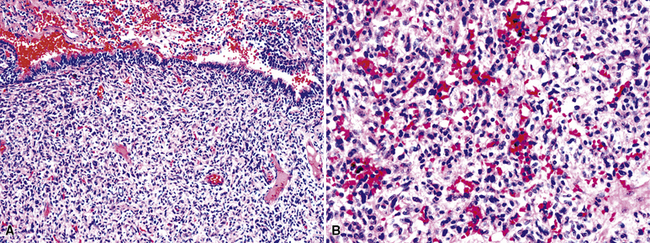

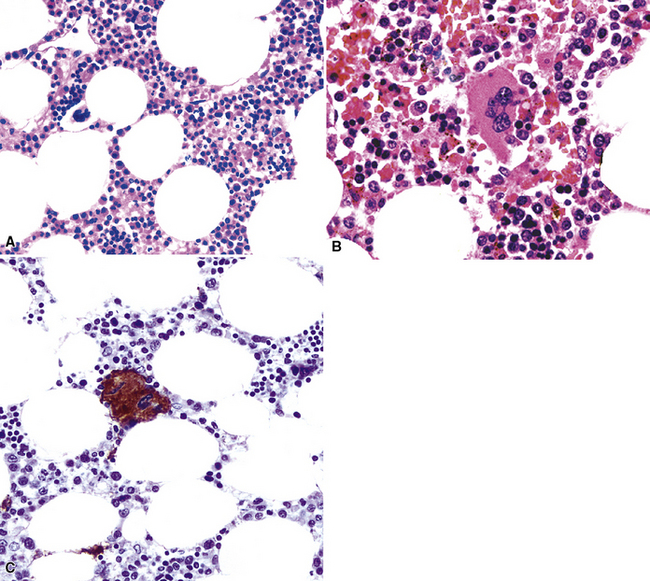

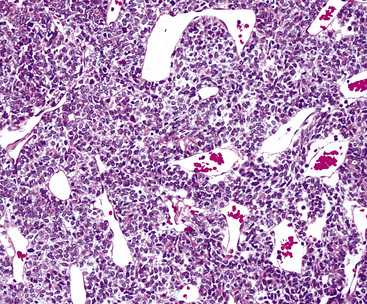

Myelolipoma

Myelolipoma is a peculiar lesion that is typically located in the adrenal glands or the retroperitoneum.263,264 As its name suggests, it comprises a tumefactive admixture of mature adipose tissue and hematopoietic precursor cells, including megakaryocytes (Figs. 19-69 and 19-70). It is still unclear whether myelolipoma represents a true neoplasm or a peculiar form of extramedullary hematopoiesis; the difference between those entities may sometimes be only semantic. Alternatively, myelolipoma could be regarded as a lipoma that has been secondarily populated by bone marrow elements.

In any event, anecdotal reports have been made of primary pulmonary myelolipoma, all of which occurred in adult patients.265–269 They may occur multiply and mimic metastases.265

Benign Tumors of the Pleura

Adenomatoid Tumor

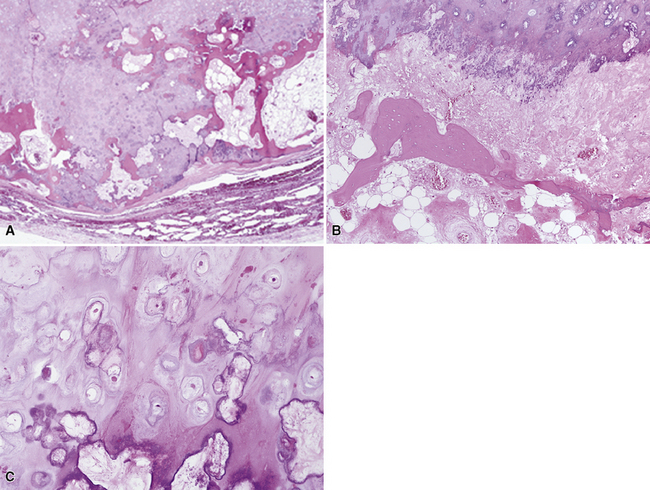

It is an unfortunate truism that completely benign neoplasms of the pleura are a distinct rarity. Indeed, the only representative of that diagnostic category is the adenomatoid tumor. That neoplasm is a lesion with mesothelial differentiation that is most often encountered in the adnexal soft tissue surrounding the uterus and testes.270,271 Only five cases have been described in the pleura.272–275 These lesions occurred in a middle-aged man, two middle-aged women, an elderly woman, and an elderly man. They were all incidental findings during surgical procedures that were done for unrelated lesions (pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma, mesothelioma, pulmonary adenosquamous carcinoma, esophageal adenocarcinoma, and pulmonary histoplasmoma), and they showed no subsequent evidence of aggressive behavior.

Pleural adenomatoid tumors are unencapsulated and measure 0.5 to 2.5 cm in greatest dimension. Microscopically, the lesions are composed of epithelioid cells organized into compact gland-like profiles (Fig. 19-71). They have vesicular nuclear chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and relatively abundant eosinophilic or vacuolated cytoplasm. No areas of nuclear pleomorphism should be present, mitotic figures are rare, and they do not invade the subjacent lung parenchyma.

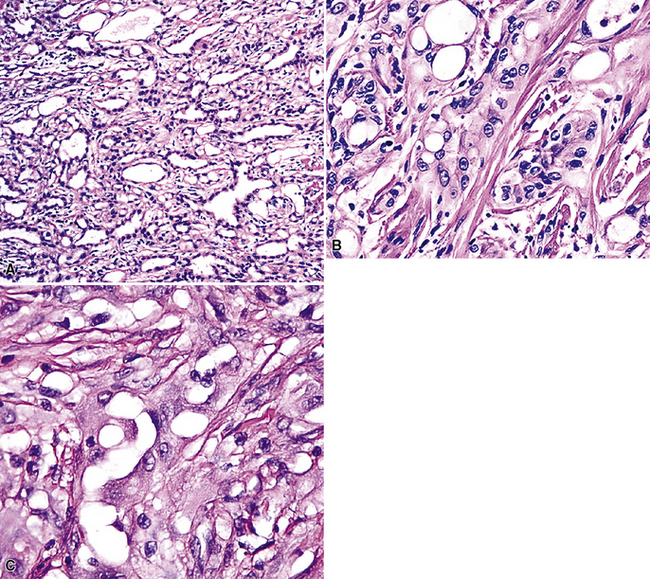

Figure 19-71 A to C, Pleural adenomatoid tumor comprised of microcystic arrays of bland cuboidal epithelioid cells.

Electron microscopy272 shows branching plasmalemmal microvilli and prominent intercellular attachment complexes, typical of mesothelial lesions. Immunohistologically, the tumor cells label for keratin and calretenin, but are negative for carcinoembryonic antigen, CD15, CD34, Ber-EP4 antigen, and tumor-associated glycoprotein 72.

The principal components of the differential diagnosis for pleural adenomatoid tumor are metastatic adenocarcinoma and malignant mesothelioma. Both of those possibilities are rendered unlikely by the bland histologic images of pleural adenomatoid tumor, with no evidence of infiltrative growth (see Chapter 20). Ki-67 (MIB-1) staining may also be helpful in this setting275 because the labeling index in adenomatoid tumor is only 1% to 2%. In contrast, “microcystic” (adenomatoid tumor–like) mesothelioma of the pleura shows a high Ki-67 index (>50%).274

Calcifying Fibrous Pseudotumor

An unusual entity known as calcifying fibrous “pseudotumor” (CFPT) has been described in the pleura.276–279 This lesion is histologically similar, if not identical, to calcifying fibrous “pseudotumors” of the soft tissue.280

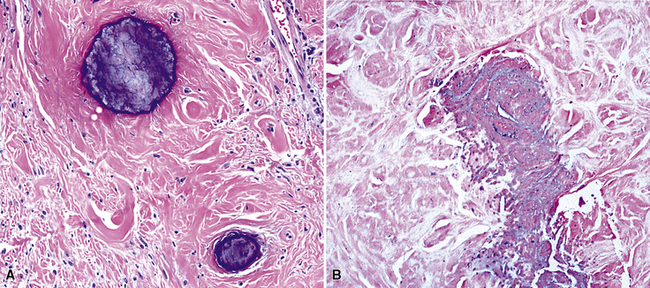

The documented cases of pleural CFPT have occurred in adults (age range, 23–46 years), most of whom were women. Pleural-based masses281,282 are present on chest radiographs, and CT scans demonstrate well-demarcated, partially calcified nodular lesions, measuring up to 12 cm in diameter (Fig. 19-72). An intrapulmonary CFPT has been reported.283

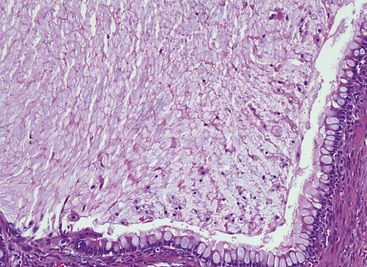

Histologically, the masses are circumscribed nonencapsulated fibrous lesions composed of dense, hyalinized, collagenous tissue, with interspersed bland spindle cells (Fig. 19-73). They are generally hypocellular, particularly at the periphery, without nuclear atypia. A scant chronic inflammatory infiltrate may be seen, without lymphoid aggregates, giant cells, or necrosis. All lesions also feature calcifications of the psammomatous (Fig. 19-74) as well as dystrophic types. These histologic features are identical to those of calcifying fibrous pseudotumors of soft tissue.284–286

Biologically Borderline Tumors of the Lung and Pleura

Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor (“Inflammatory Pseudotumor”)

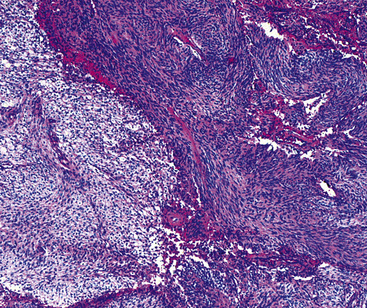

In 1939, Brunn289 described two pulmonary lesions that were composed of spindle cells admixed with inflammatory elements in patients with fever and weight loss. The systemic symptoms disappeared after surgical removal of the lung tumors. Although they were believed to be true neoplasms of probable smooth muscle lineage, subsequent authors espoused the theory that masses with the same attributes were inflammatory and reparative lesions.290,291 Hence, the term “inflammatory pseudotumor” gained favor. However, Spencer292 noted that a proportion of such proliferations behaved in a biologically malignant fashion, and other reports also documented the presence of vascular invasion and recurrences.293–295 Molecular analyses done in the 1990s revealed a clonal character of some “inflammatory pseudotumors” in the lungs and other anatomic sites,296–298 and, together with aggregated clinicopathologic information, these data resulted in amendment of their name to “inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors.”299 It is now accepted that they are separate from inflammatory pseudotumors and that IMTs form a conceptual continuum with “inflammatory fibrosarcoma” or “myofibrosarcoma,”300–303 Because they may recur and occasionally metastasize, IMTs are best considered biologically “borderline” neoplasms.

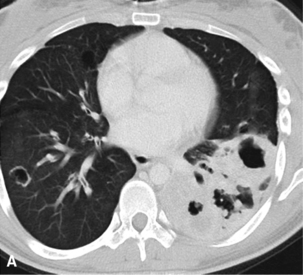

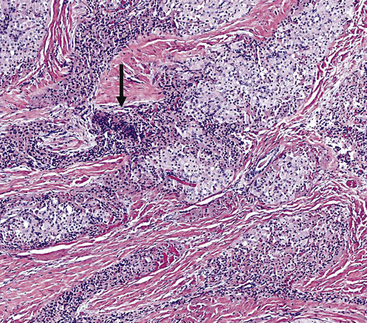

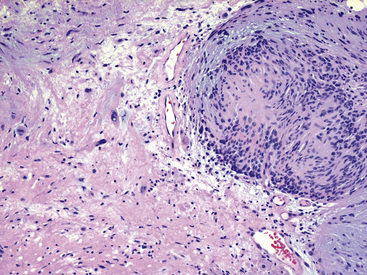

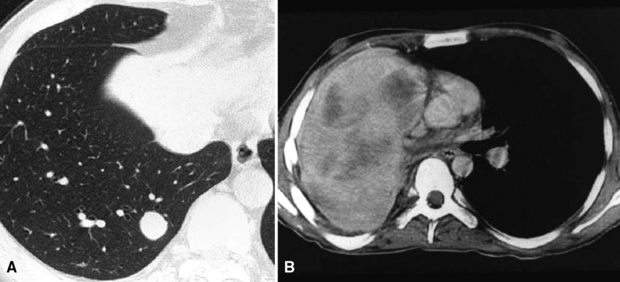

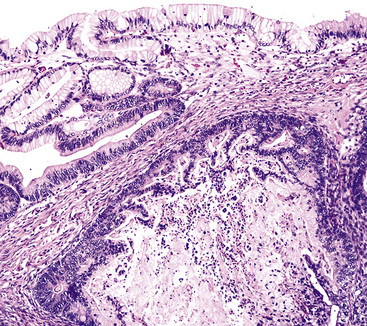

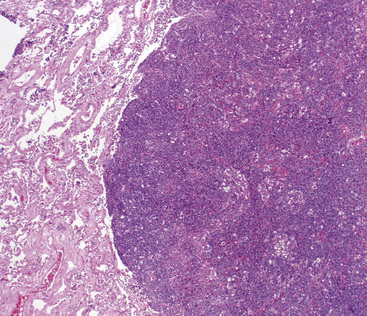

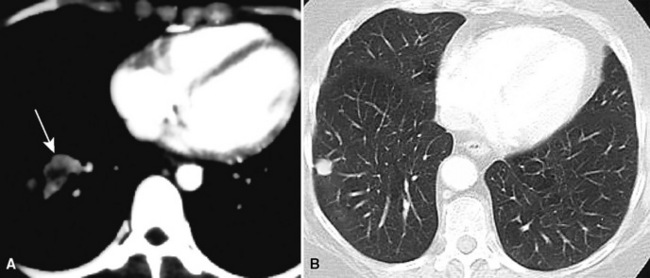

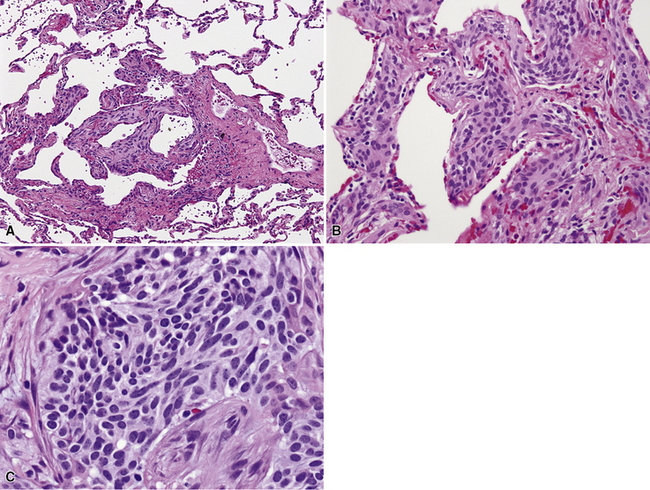

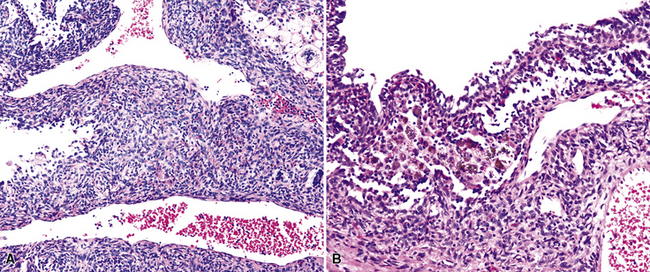

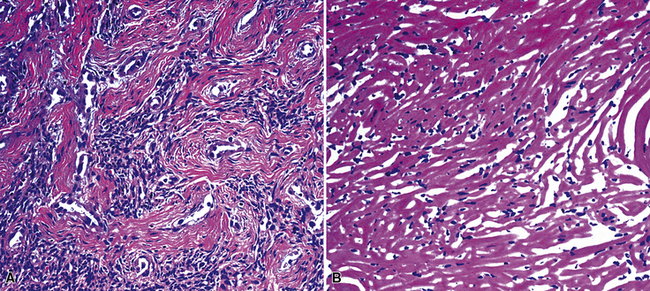

The lung is most frequently affected by IMT, among all potential topographic locations.295 Although the majority of IMTs are seen in children and young adults, they may be encountered in patients of all ages, with no sex predilection.295 Some IMTs are situated in the large airways, with no parenchymal involvement, but they are exceptional; most arise in the peripheral lung fields. Systemic symptoms of a paraneoplastic nature have been reported in up to 50% of cases, including such findings as anemia, fever, weight loss, hyperglobulinemia, leukothrombocytosis, and elevations in the erythrocyte sedimentation rate.301,303 As discussed earlier, those abnormalities typically remit when the IMT is removed. The remaining cases present with cough, vague chest discomfort, or hemoptysis, or are asymptomatic, with the lesions found incidentally on chest radiographs.299 On imaging studies, IMT is typically a lobulated or globoid mass (Fig. 19-75), usually measuring less than 5 cm in maximum dimension. Occasionally, it may attain a size of greater than 10 cm; internal calcifications are commonly seen. Infiltration of great vessels, mediastinal soft tissue, or chest wall is apparent radiographically in a minority of cases.

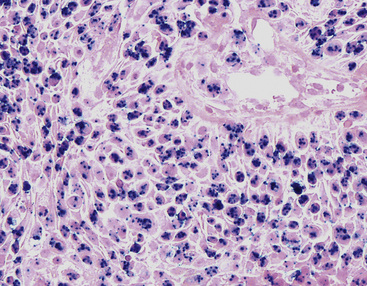

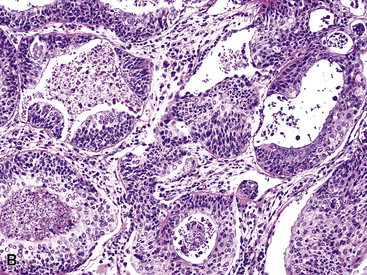

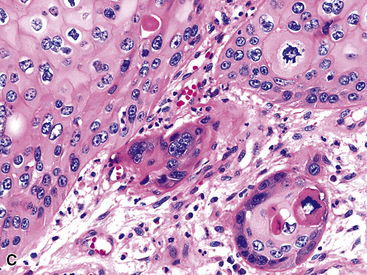

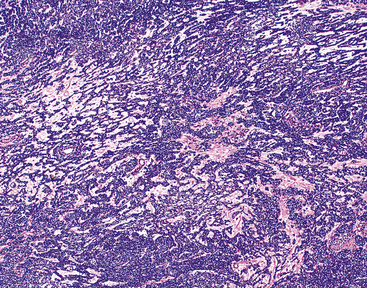

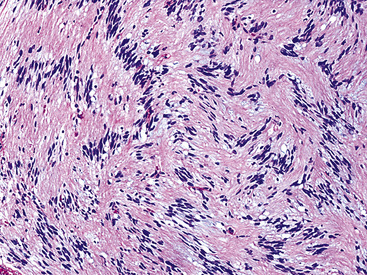

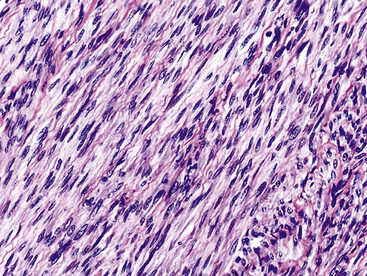

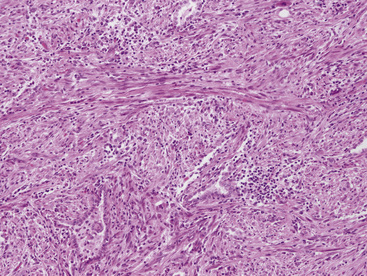

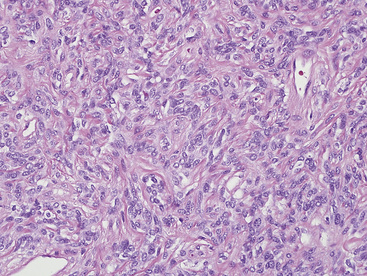

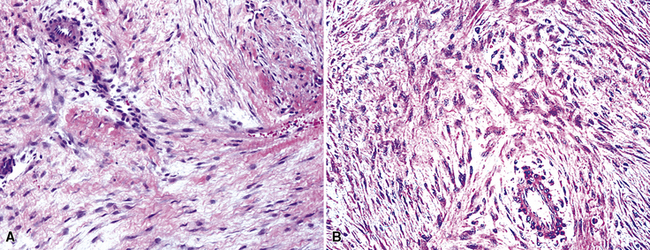

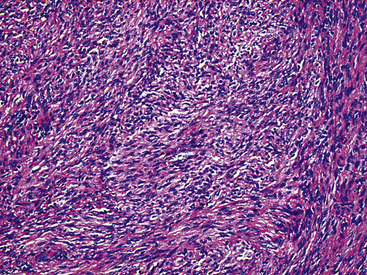

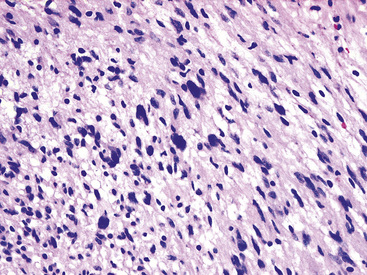

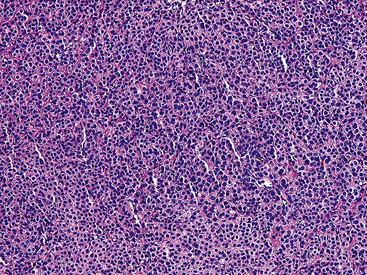

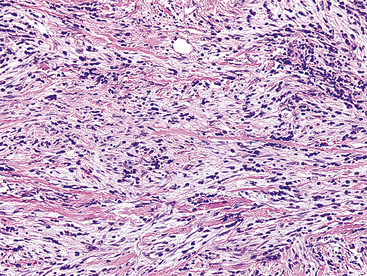

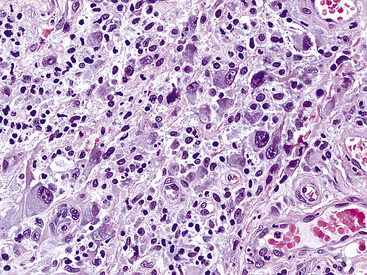

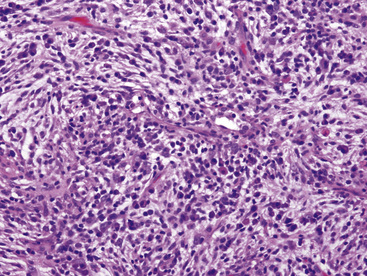

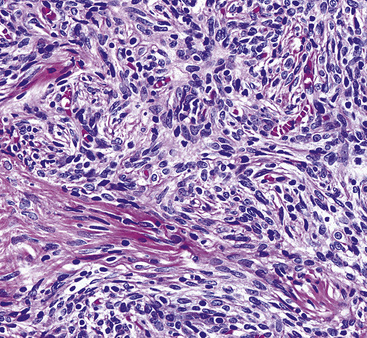

The histologic profile of IMT features a proliferation of relatively bland spindle cells arranged haphazardly or in vague fascicles299,301,304 (Figs. 19-76 and 19-77). In contrast to the gross appearance, this lesion has an irregular peripheral zone of growth microscopically, with tongues of tumor that comingle with adjacent normal tissues. Not surprisingly, infiltration of blood vessels, bronchi, and pleura may be evident. Nuclei in the neoplastic fusiform elements usually contain dispersed or vesicular chromatin with compact nucleoli (Fig. 19-78). Mitotic activity is typically easily found, but without pathologic division figures. Cytoplasm is amphophilic or lightly eosinophilic and may show a faintly fibrillar character. Admixed inflammatory cells are greatly variable in density and type, and some cases of IMT show virtually none. Lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, eosinophils, and neutrophils are also potentially represented (Fig. 19-79), and intralesional aggregates of xanthomatized foam cells are sometimes apparent. Some cases demonstrate rather striking zones of sclerosis, and these may even be hyalinized. On the other hand, 20% to 30% of these lesions show dense cellularity with focal or global nuclear atypia, relatively high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios, nuclear hyperchromasia, mild nuclear pleomorphism, and zones of necrosis.295

Figure 19-77 The spindle cells in this pulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor are arranged in interweaving bundles.

Figure 19-78 This area in an inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor demonstrates moderate pleomorphism of the constituent tumor cells.

Figure 19-79 Intralesional lymphocytes and plasma cells are numerous in this pulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor.

Electron microscopic evaluation of IMTs shows that the tumor cells possess some features associated with smooth muscle, such as plasmalemmal dense patches, pinocytotic vesicles, and cytoplasmic bundles of thin (actin-type) filaments. Pericellular basal lamina is variably present, but there are no intercellular attachment complexes.299

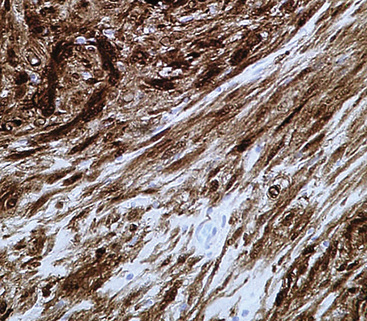

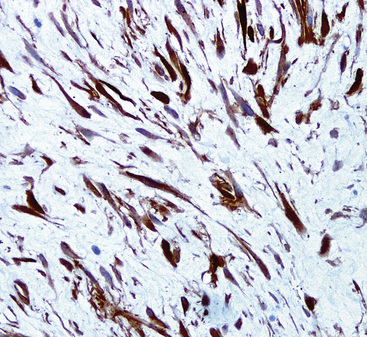

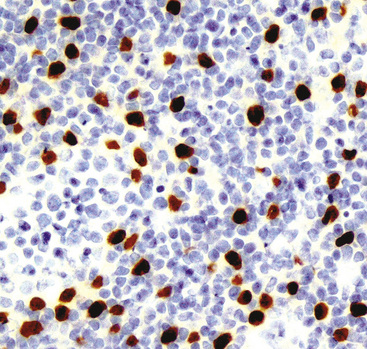

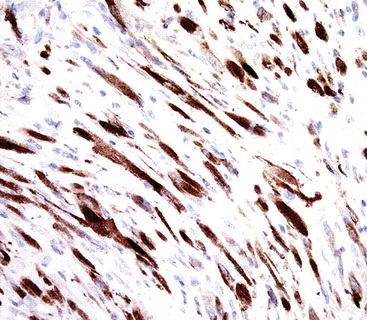

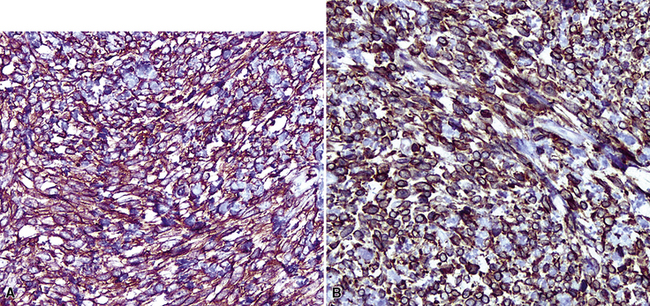

By immunohistochemical assessment, the spindle cells react with antibodies to vimentin, alpha-isoform and muscle-specific actins, and calponin, but usually not with desmin, caldesmon, CD34, or keratin.301 Mutant p53 protein is detectable immunohistologically in fewer than 10% of cases.298 On the other hand, two proteins that relate to reproducible cytogenetic abnormalities in chromosome 2p23 in IMTs are detectable in approximately 40% of these lesions. These are known as “anaplastic lymphoma kinase 1” (ALK-1; Fig. 19-80) and “p80,” and were originally studied in anaplastic large-cell (“Ki-1”) lymphomas.305 Coffin and colleagues306 found that ALK-1 reactivity predominated in IMTs of patients 20 years of age and older; those lesions also were more likely to demonstrate cytomorphologic atypia.

Figure 19-80 Diffuse immunoreactivity is present for ALK-1 protein in this inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the lung.

The differential diagnosis of pulmonary IMT includes tumefactive organizing pneumonia304; “true inflammatory pseudotumor” or “plasma cell granuloma” (see Chapter 18); immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4)-predominant lymphoplasmacytic lesions307; smooth muscle proliferations in the lung; inflammatory sarcomatoid carcinoma295 (Fig. 19-81); and inflammatory malignant fibrous histiocytoma. ALK-1/p80 reactivity is diagnostic of IMT in this setting, but as mentioned earlier, is seen in only a minority of cases. The spindle cells of inflammatory sarcomatoid carcinoma can be labeled for keratin and epithelial membrane antigen, in contrast to those of IMT.295,308 Inflammatory malignant fibrous histiocytoma is typically nonreactive for actins or calponin, as seen in IMT. Spindle cells in organizing pneumonia typically form smaller whorls of spindle cells than IMT.302 IgG4-predominant lymphoplasmacytic lesions are, by definition, recognized by a preponderance of IgG4-immunoreactive cells in the inflammatory components.307

There are few if any pathologic variables that can be used successfully in any given case of IMT to predict its biologic behavior with certainty.309 Some examples of pulmonary IMT have been observed for extended periods with minimal growth. Spontaneous complete resolution has also been recorded, and a few lesions have diminished in size after nonsurgical therapy.301 Operative removal is usually necessary to establish a firm diagnosis of IMT, and if the lesion has been completely excised, no further intervention is required. On the other hand, it is logical to expect that incomplete removal—particularly if invasion of adjacent extrapulmonary tissues is present—might, in some instances, be followed by continued growth.310 In particular, involvement of the pleura, pulmonary hilum, diaphragm, or mediastinum is associated with morbidity from IMTs of the lung. They may even, exceptionally, prove fatal if they are massive and infiltrate the mediastinum extensively, or if distant spread occurs. Overall, recurrence of IMT is seen in approximately 55% of cases, and roughly 10% metastasize.306

Sclerosing Hemangioma (“Pneumocytoma”)

More than 50 years ago, Liebow and Hubbell311 described a peculiar tumor of the peripheral lung parenchyma with a sclerosing, angiomatoid, and papillary architecture. They gave it the name “sclerosing hemangioma,” but this designation was chosen in unfortunate mimicry of a convention then extant in dermatopathology. In the 1950s, the lesion now known as “dermatofibroma” or “cutaneous fibrous histiocytoma” was likewise commonly called “sclerosing hemangioma,”312 because it sometimes showed internal blood lakes and hemosiderosis. In their seminal description of “sclerosing hemangioma” of the lung, Liebow and Hubbell disavowed an endothelial derivation for the tumor and appended the alternative appellations of “histiocytoma” and “xanthoma,” perhaps in deference to the true identity of its alleged dermal analog. This enigmatic series of nosologic and terminologic choices set the stage for confusion in the succeeding decades. Various studies of the cellular nature of pulmonary “sclerosing hemangioma” have suggested vascular, fibrohistiocytic, mesothelial, and epithelial lineages,313–317 and controversies over such proposals persist to some extent.

Based on the aggregated data,318,319 this tumor is properly considered as a neoplasm showing differentiation that is most like that of embryonic (uncommitted) respiratory epithelium. Therefore, the entity in question is best designated as “pneumocytoma,” as suggested by Shimosato320; however, the World Health Organization has persisted in using the historic name “sclerosing hemangioma.”

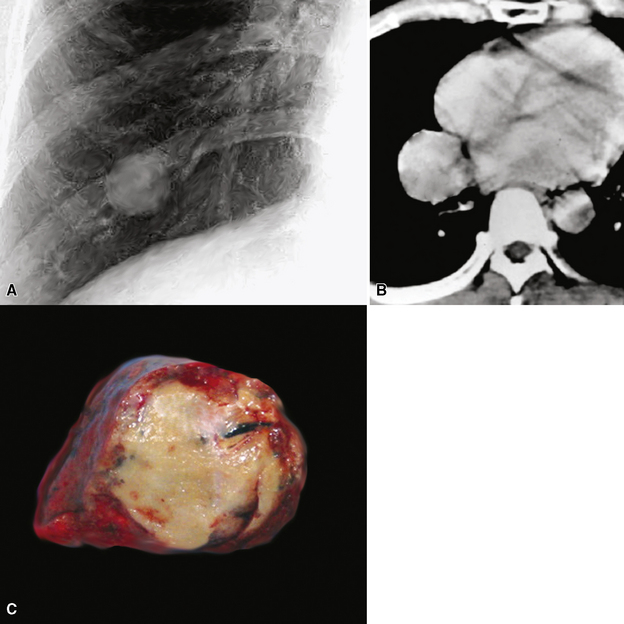

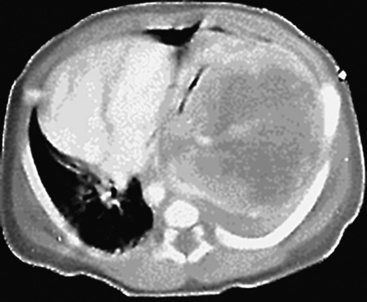

Sclerosing hemangioma can affect patients of almost any age, from early childhood321 through the end of life. Females predominate by a factor of 5:1.322–332 Only approximately 20% of patients have any respiratory symptoms at the time their tumors are found. It may arise in any of the pulmonary lobes; localization in the large airways, pleura, and mediastinum has been rarely reported.322,333

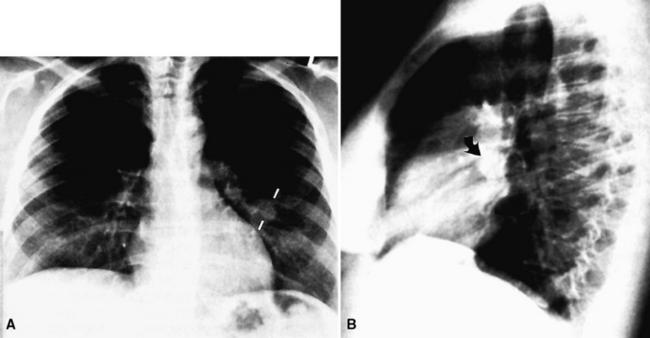

Radiographically, patients with sclerosing hemangioma usually have solitary peripheral masses with well-defined homogeneous round or oval profiles on chest roentgenograms (Fig. 19-82). CT shows homogeneity and high density of the lesions in the great majority of cases (Fig. 19-83); low-density areas may be apparent in some tumors because of cystic change. In addition, the “air meniscus sign” (also known as the “air trapping” or “air crescent” sign)327,328,334—a rim of air that partially or circumferentially surrounds a mass—is evident in the lung parenchyma adjacent to some lesions of this type.

Figure 19-83 A sclerosing hemangioma. This computed tomogram of the lesion shown in Figure 19-82 shows a circumscribed spherical tumor with a uniform internal density.

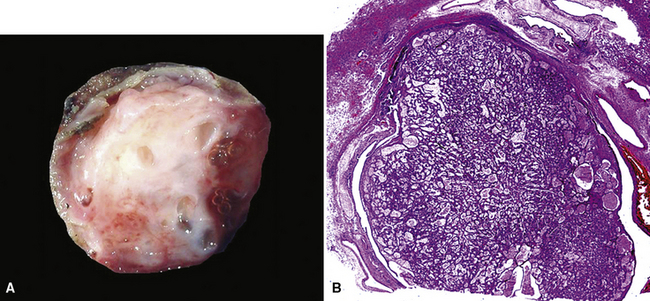

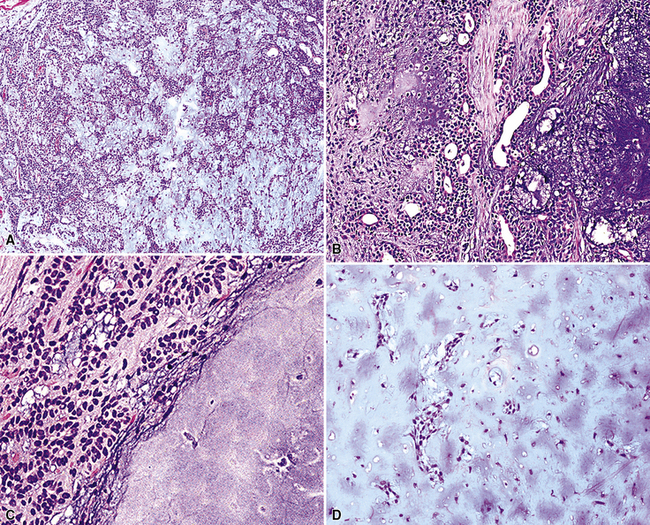

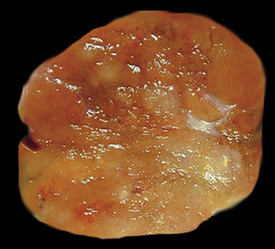

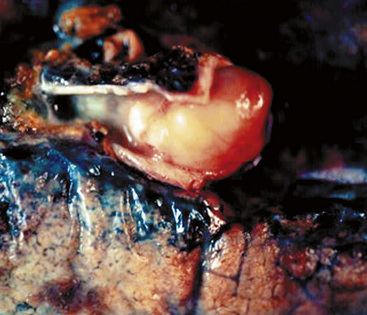

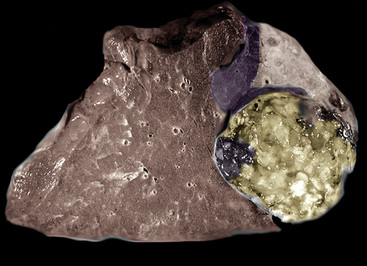

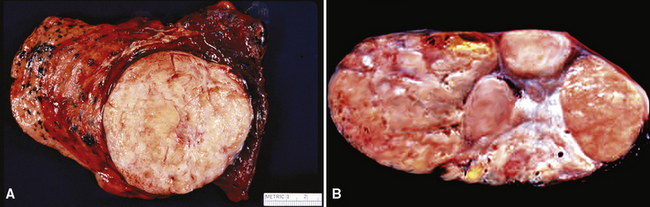

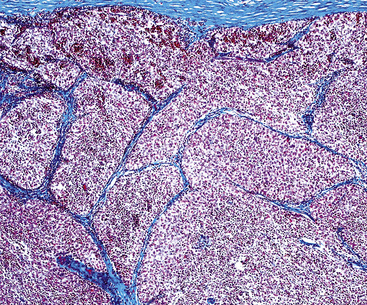

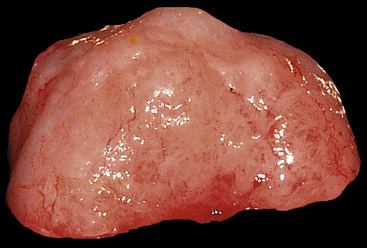

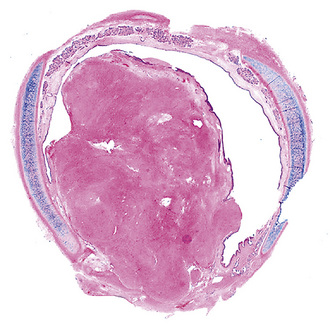

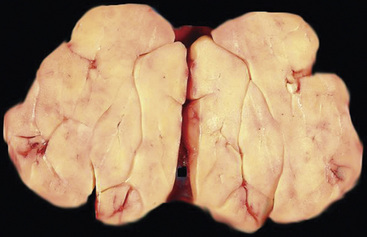

Grossly, most sclerosing hemangiomas are less than 3 cm in maximum dimension (Fig. 19-84), but sometimes they attain a size of up to 10 cm. Multifocality, sometimes featuring a satellitotic configuration of small nodules around a dominant central nodule,322 is apparent in approximately 4% of cases.335 Roughly the same proportion are pleural-based and may be polypoid, potentially simulating the appearance of solitary fibrous tumors.322 Sharp circumscription from the surrounding lung parenchyma is the rule, so much so that these tumors are sometimes “shelled out” by the surgeon with little if any attached alveolated tissue. Their cut surfaces are tan-gray, yellow, or mottled. Cystic areas are evident in roughly 3% of cases; 20% show areas of intralesional hemorrhage, which may be extensive.

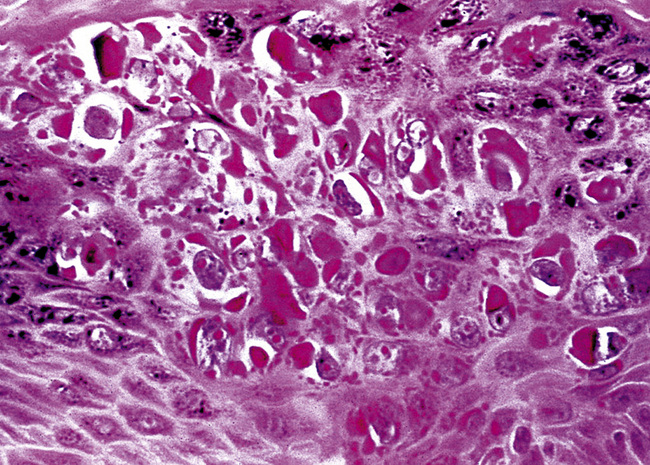

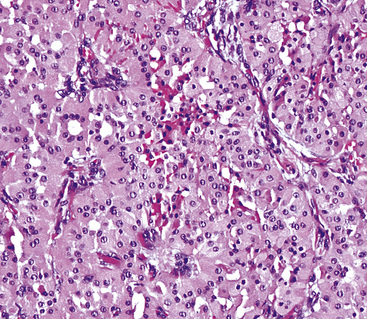

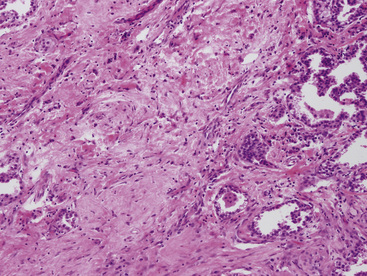

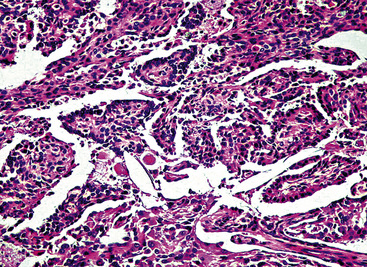

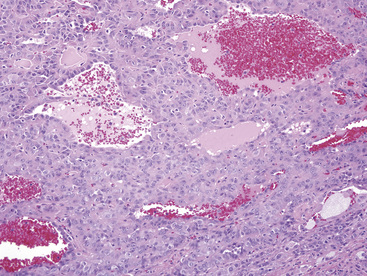

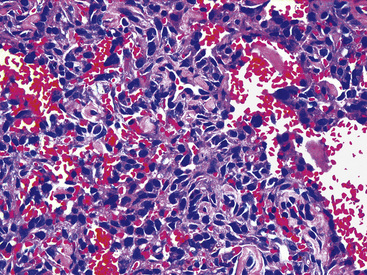

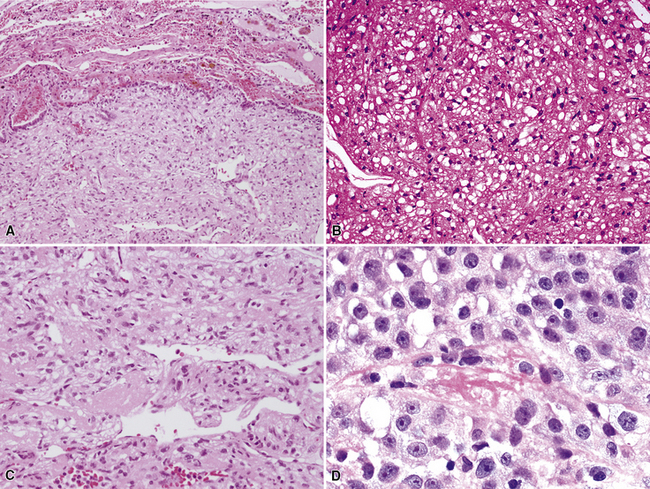

The histologic images of sclerosing hemangioma include varying admixtures of four basic growth patterns—sclerotic (Fig. 19-85), papillary (Fig. 19-86), solid (Fig. 19-87), and hemorrhagic/angiomatoid (Fig. 19-88). Approximately 15% of cases are monomorphic, and roughly 20% contain areas representing all of the patterns in the same lesion. Two basic cell types comprise the neoplastic elements in sclerosing hemangioma—“surface” cells, which mantle papillary projections, and “round” cells, seen in the cores of papillary structures and in solid sheets within the lesions. Surface cells often show intranuclear invaginations of cytoplasm, yielding “pseudoinclusions” such as those seen in type II pneumocytes and Clara cells. They also may be multinucleated. Round cells are actually polygonal, with oval nuclei, dispersed chromatin, indiscernible nucleoli, and extremely rare mitotic figures. They may focally exhibit cytoplasmic vacuolation and even assume the morphologic features of a signet ring cell. Rarely, nuclear hyperchromasia and moderate pleomorphism are seen in the round cell element.322,336

Secondary features of sclerosing hemangioma include blood lakes in angiomatoid foci; limited areas of necrosis; stromal hemosiderosis, calcification, cholesterolosis, or combinations thereof; internal cystification, with mucinous contents; granulomatous inflammation; and a potential association with foci of neuroendocrine hyperplasia (“tumorlets”) in the surrounding lung parenchyma.322,323,336,337

We have previously stated our opinion that pneumocytoma/sclerosing hemangioma, alveolar adenoma, and papillary adenoma comprise a biologically interrelated family of pulmonary lesions. Nevertheless, these entities differ morphologically, in that sclerosing hemangioma lacks the “Swiss cheese” microcystic structure of alveolar adenoma and papillary adenoma does not contain the “round cell” elements of sclerosing hemangioma.158

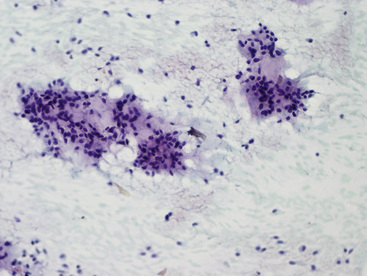

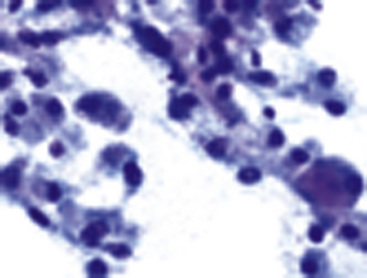

Several publications have addressed FNA biopsy findings in sclerosing hemangioma, and most have noted substantial morphologic overlap between those lesions and well-differentiated adenocarcinomas (particularly of the bronchioloalveolar type).326,329,330,338–340 A shared potential for nuclear atypia, intranuclear pseudoinclusions, and micropapillary growth in both tumor entities makes the definitive cytologic recognition of sclerosing hemangioma very difficult (Fig. 19-89). Despite assertions that it can be accomplished,341 we believe that an unqualified interpretation of sclerosing hemangioma by FNA biopsy is unwise. In appropriate cases, that possibility can be included in the diagnostic report, prompting an intraoperative frozen-section examination to further guide the surgeon’s choice of procedure. This proviso relates to the very close cytologic similarity we have noted between pneumocytoma and selected adenocarcinomas.

Electron microscopy of sclerosing hemangiomas has shown that both the surface cell and round cell components demonstrate type II pneumocytic features, containing cytoplasmic lamellar bodies with variable levels of maturation.315,322 Other organelles are nonspecific. These findings support the interrelatedness of sclerosing hemangioma and papillary adenoma.

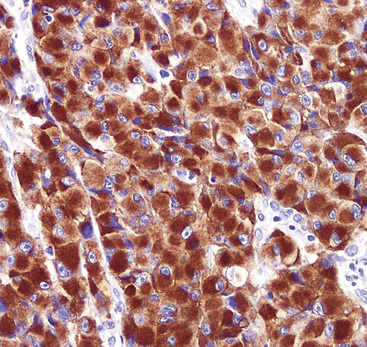

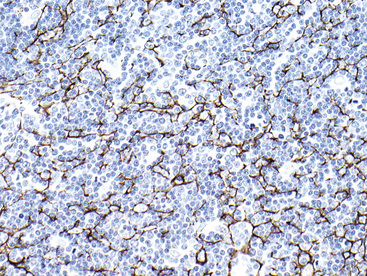

Immunohistologically, variable reactivity has been seen for keratin, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), surfactant-related proteins, Clara cell antigen, and thyroid transcription factor 1 in both cellular components of sclerosing hemangioma322,331,332,338,342–349 (Fig. 19-90). Receptors for estrogen and progesterone are also demonstrable in a minority of cases.322 On the other hand, mesothelial markers, such as calretinin, HBME-1, cytokeratin 5/6, and WT-1 protein are absent in these lesions, as are neuroendocrine, neural, and myogenous determinants.

Justification for inclusion of sclerosing hemangioma as a “borderline” lesion stems from reports of its recurrence341,350 and the finding of lymph nodal metastases in 10 patients to date.322,324,351–353 In the U.S. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology series, this behavior was observed in 1% of cases.322 Despite that observation, no patient with metastatic tumor has died of the tumor, and lymph node involvement324 does not appear to affect survival.

As mentioned earlier, the principal differential diagnostic alternative to sclerosing hemangioma is low-grade adenocarcinoma of bronchioloalveolar or conventional types. 330,339,340 An adequate tissue sample—allowing for evaluation of the architecture of the entire mass—is essential to making that distinction. Another diagnostic possibility is the papillary variant of low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma,354 but its particular histologic pattern, with an intimate admixture of mucinous and squamous epithelium, should allow for a distinction from sclerosing hemangioma.

Pulmonary Mucinous Cystadenoma and Borderline Mucinous Tumor

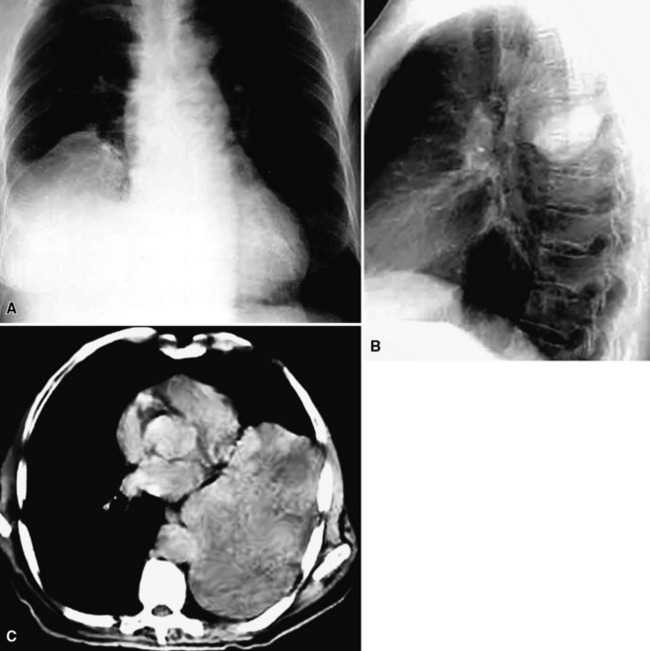

Mucinous cystadenomas and cystic mucinous tumors of low malignant potential—“borderline” mucinous neoplasms (BMTs)—are well known to gynecologic and gastrointestinal pathologists because they rather commonly arise in the ovaries, gut, and pancreas.355,356 A primary origin in the lung for such lesions is unusual, but possible, and approximately 50 cases have been reported.357–369 These neoplasms occur in adults as solitary lesions in the peripheral parenchyma. An association with von Hippel-Lindau disease has been reported.369 Both plain films and CTs of the thorax clearly show the cystic nature of these tumors (Fig. 19-91), which generally measure several centimeters in diameter.

Figure 19-91 This chest radiograph shows a large ovoid mass in the right lower lung field, representing a cystic mucinous tumor.

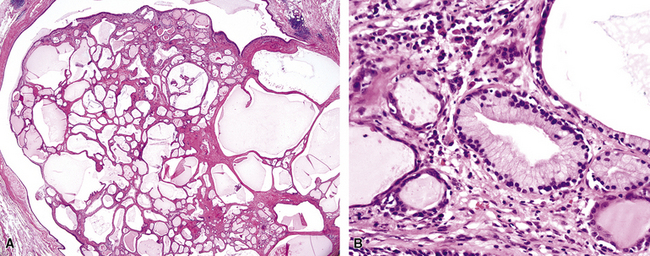

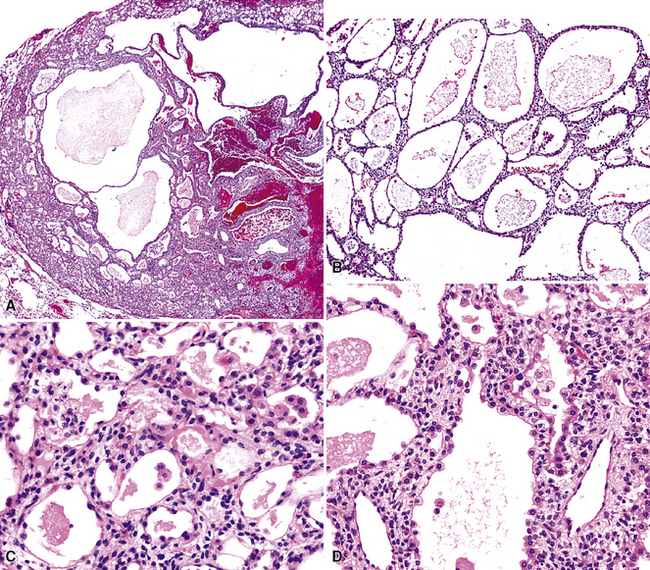

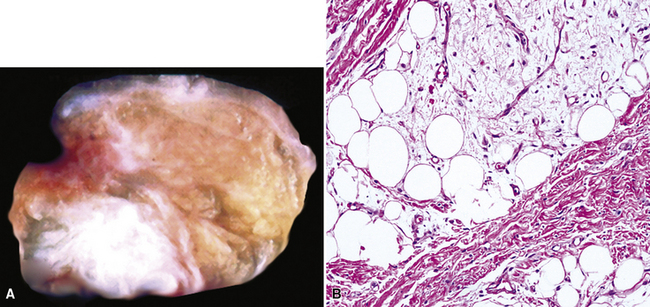

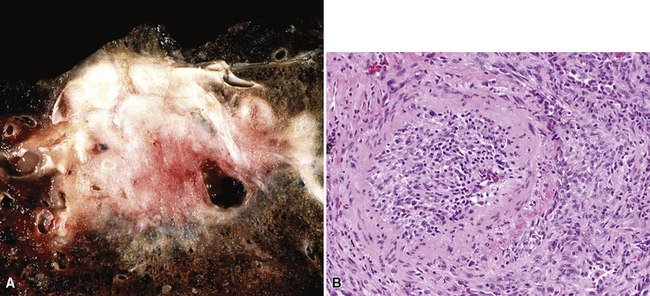

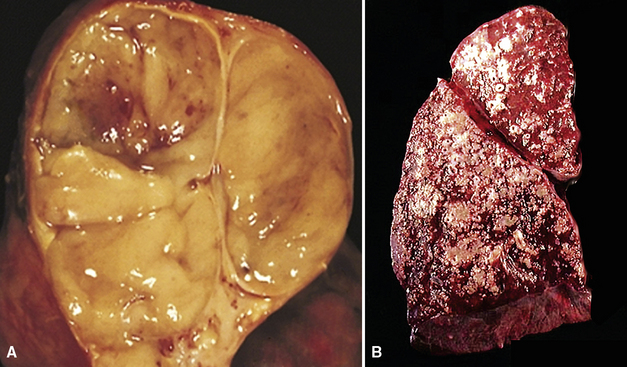

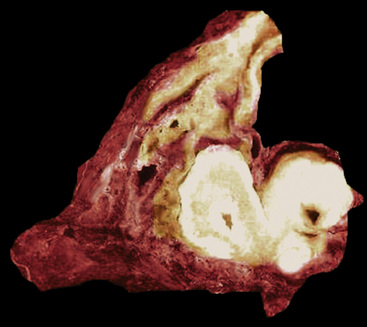

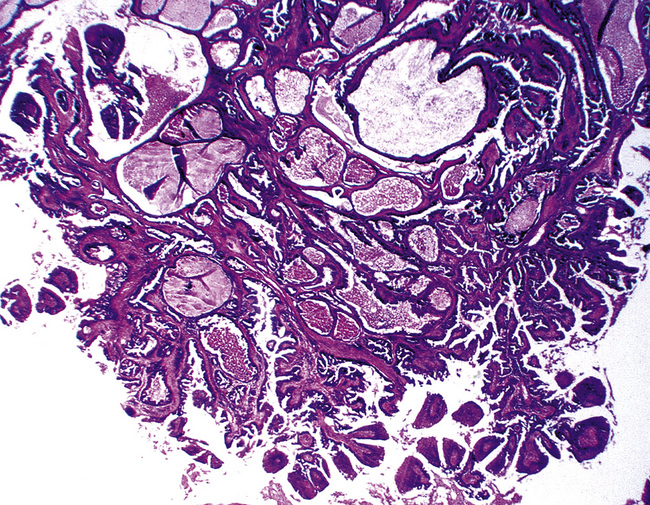

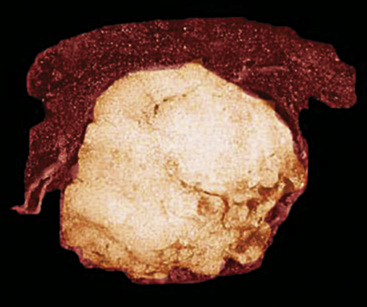

Grossly, mucinous cystadenomas and BMTs are sharply demarcated from the surrounding lung parenchyma (Fig. 19-92) and may even “shell out” for the surgeon. Their walls are relatively thick and fibrous, enclosing locules that contain thick viscous mucoid material. Foci of granular tissue are present on the internal aspects of the cysts, representing epithelial projections.

Histologically, the latter structures comprise cytologically bland mucin-containing tumor cells that are cuboidal or low columnar (Fig. 19-93). Nuclei are generally basally located and relatively banal, with no pleomorphism or mitotic activity (Fig. 19-94). Cystadenomas do not demonstrate invasive growth into the fibrous walls of the lesions, but BMTs may do so, and may manifest a “piling up” of lesional epithelium that yields complex micropapillary structures (Fig. 19-95). Cases in which frank adenocarcinoma evolved from pre-existing pulmonary mucinous cystadenoma have been reported (Fig. 19-96).358,364,368

Figure 19-95 Micropapillary growth is evident in some cystic mucinous tumors of the lung, justifying use of the term “borderline.”

The classification of pulmonary BMT as a neoplasm with low malignant potential is supported by the observations of Gao and Urbanski.368 Those authors documented a mortality rate (due to metastatic tumor) of 30% in their series, with up to 10 years of postoperative surveillance, raising the possibility that these should be considered frank carcinomas rather than borderline lesions. They further described a spectrum of histologic appearances in the epithelium of BMT, ranging from completely bland to overtly malignant. Pathologic findings that were proposed as adverse prognosticators included solid epithelial growth at the periphery of the lesion, adhesion of the tumor to the pleura, crossing of the intrapulmonary septa by the tumor, obvious nuclear atypicality, and invasive growth into the surrounding lung tissue.368

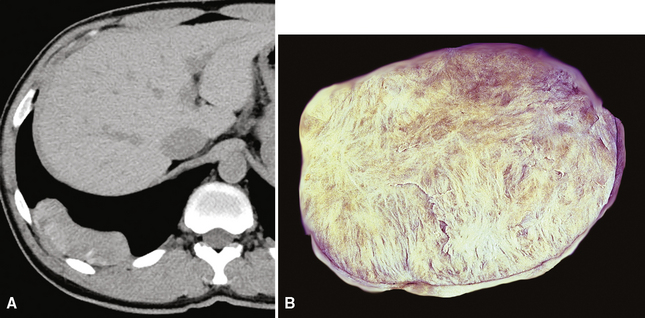

Solitary Fibrous Tumor

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT; formerly called “fibroma”)370,371 of the lung and pleura is still confused by some clinicians with mesothelial neoplasms. That is because of a nosologic scheme advanced by Klemperer and Rabin in 1931372 that was used for many years thereafter and gave SFT the designation of “localized fibrous mesothelioma.” Particularly in the last two decades, much work has been done that unequivocally shows that SFT lacks mesothelial differentiation373; instead, this tumor is composed of facultative fibroblastic elements such as those seen in the submesothelial zone of the normal lung. Even though it may occasionally recur and sometimes demonstrates locally aggressive growth—justifying its classification as a “borderline” mesenchymal tumor—SFT generally has a favorable prognosis that differs markedly from that of mesothelioma.373–383 Likewise, pleural fibrous tumors have no etiologic relationship whatsoever to occupational-level asbestos exposure, in contrast to a proportion of mesotheliomas.381

Approximately two mesotheliomas are encountered for every SFT in general thoracic surgical practice.373 Outside of infancy, patients of any age may have an SFT, but they are most often seen in patients older than 40 years old, with no sex predilection. The great majority of cases present with an asymptomatic pleuropulmonary mass that is seen on screening radiographs. Rarely, one of two paraneoplastic complexes accompanies SFT; those are represented by hypertrophic osteoarthropathy and tumor-associated hypoglycemia (Doege-Potter syndrome).381 The cause of the first condition is unknown; the second is related to an insulin-like growth factor that is produced by the neoplastic cells.

Radiographically, SFT may be as small as 1 cm in maximal dimension or as large as 36 cm. Occasional lesions of this type have occupied virtually an entire hemithorax and weighed in excess of 5 kg.380 They are usually globoid neoplasms with a relatively homogeneous internal density, but cystic change, calcification, or foci of necrosis may be sometimes apparent (Fig. 19-97). A minority of cases demonstrate a pedicle that attaches an SFT in the pleural space to the pleura itself. Conversely, other lesions “invert” into the lung parenchyma or may arise from interlobar pleural reflections, producing the appearance of a peripheral intrapulmonary mass370,371,384–388; large tumors also may displace the trachea or intramediastinal structures.373 Rarely, overt invasion of the chest wall, vertebral bodies, or adjacent lung tissue is apparent on imaging studies.384,389 A small number of SFTs show regional satellitotic growth in the pleura.388

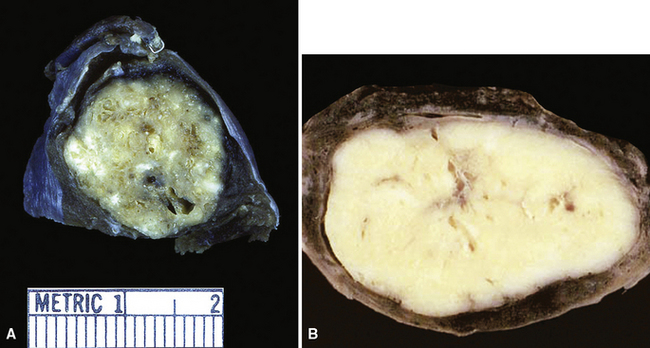

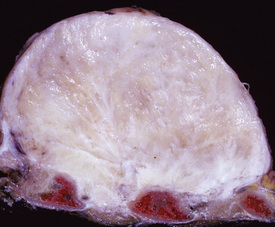

Gross examination shows a lobulated mass that is invested by pleural tissue (Fig. 19-98). Cut surfaces can be homogeneous, tan-gray, and vaguely “whorled,” or may show distinct internal septa and foci of degeneration, mucoid change, hemorrhage, calcification, or necrosis.383,384 Intralesional cystic change can also be present.

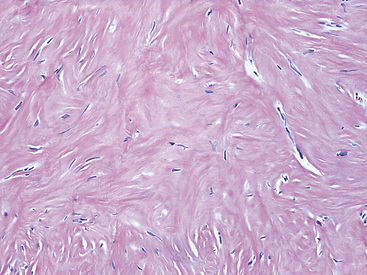

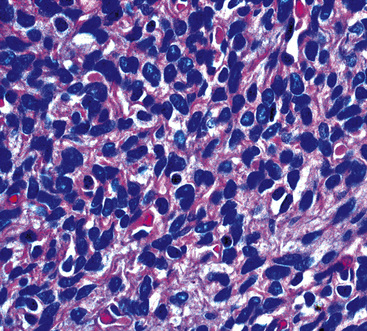

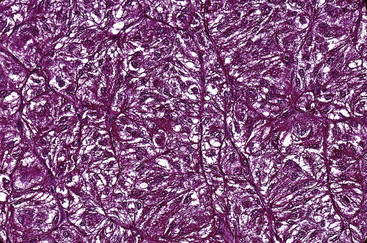

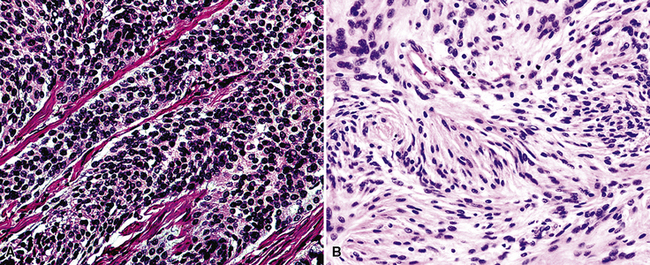

The microscopic spectrum of pleuropulmonary SFT is broad.383 A solid spindle cell growth and a diffuse sclerosing pattern are most frequent. In the first of these configurations, fusiform cells are arranged in random arrays (a “patternless pattern”) (Fig. 19-99), with fascicular groupings, storiform or herringbone patterns, or regimented arrays with nuclear palisading. SFT may also have epithelioid cells (Fig. 19-100) and branched intralesional blood vessels resembling “moose antlers,” as seen in hemangiopericytoma (which has been merged nosologically with SFT) or synovial sarcoma. Zones of fibrosis may be interspersed with cellular zones and dominate in lesions classified as “diffuse sclerosing” SFT (Fig. 19-101). Focal collagenous degeneration is occasionally apparent, simulating true necrosis. Less frequent features include multinucleated tumor giant cells, “amianthoid” arrays of collagen fibers, myxoid stromal change, limited areas of spontaneous necrosis, hemorrhage, and metaplastic ossification. Mitotic activity in most SFTs is present but not prominent, and division figures are normal.

Figure 19-101 A and B, Hyalinizing collagenous stroma is prominent in this solitary fibrous pleural tumor.

England and associates384 attempted a codification of criteria for malignancy in SFT. These included dense cellularity with overlapping nuclei; nuclear hyperchromasia and pleomorphism (Fig. 19-102); mitotic activity greater than four division figures per 10 high-power (×400) microscopic fields; and necrosis and hemorrhage. However, only 55% of the lesions with such features actually had an aggressive course, with recurrence, metastasis, or both. Harrison-Phipps and colleagues390 found that approximately 13% of SFTs showed the “malignant” attributes described earlier, and they also noted that the likelihood of morphologic atypia correlated directly with tumor size. In that series, “malignant” SFTs averaged 12 cm in maximal dimension, compared with 4.5 cm for tumors that lacked histologic atypia. Vallat-Decouvelaere and coworkers375 also emphasized that histologic findings in SFTs may not be accurate predictors of their behavior. In line with this admonition, a small proportion of histologically banal SFTs manifest untoward behavior, typically with invasion of the bony structures and soft tissues of the thorax, or recurrence.373,381 Because of these attributes, it is best to consider SFT a borderline neoplasm. As Vallat-Decouvelaere and colleagues375 sagely stated, “it is probably unwise to regard any such lesion as definitely benign.”

In FNA biopsy specimens,389,391,392 smears show variably cohesive and pleomorphic spindle cells in a bloody background, representing an image that corresponds to a sizable differential diagnosis. Preparation of cell block sections and procurement of adjunctive pathologic studies is essential to a specific diagnosis.

Electron microscopic analysis of SFT has shown that the tumor cells are fibroblast-like. They lack basal lamina, intercellular junctions, and plasmalemmal microvilli, as expected in epithelial or mesothelial cells, and instead contain only basic intracellular organelles.381 Occasionally, intrareticular collagen fibrils are apparent within profiles of endoplasmic reticulum.

Immunophenotypically, SFT demonstrates reactivity for vimentin, CD34, CD99, and bcl-2 protein in more than 85% of cases375,382,384,389,392–396 (Fig. 19-103). There is typically no labeling for keratin, EMA, desmin, actins, S-100 protein, collagen type IV, CD31, or CD57. Anecdotally, lesions with malignant histologic features may exhibit mutant p53 protein immunoreactivity,397 but this relationship has not been subjected to rigorous evaluation.

Figure 19-103 Diffuse immunoreactivity for CD34 (A) and CD99 (B) is characteristic of solitary fibrous tumors.

Cytogenetic assessment of SFT is still developmental. However, the most frequent defects reported in this tumor type have involved chromosomes 4q, 8, 13q, 15q, and 21q.398,399 One case has shown a balanced t(4;15)(q13;q26) translocation.399

The differential diagnosis of pleuropulmonary SFT includes primary and secondary sarcomatoid carcinoma, sarcomatoid or desmoplastic mesothelioma, fibrosarcoma, storiform malignant fibrous histiocytoma, synovial sarcoma, hemangiopericytoma, and metastatic endometrial stromal sarcoma.383 Among these possibilities, carcinomas, mesotheliomas, and synovial sarcomas may be excluded because of their immunoreactivity for keratin, EMA, or both. In addition, synovial sarcoma reproducibly shows a t(X;18) chromosomal translocation400 and nuclear immunoreactivity for transducin-like enhancer of split 1 (TLE1),401 both of which are absent in SFT. Consistent CD10 reactivity in metastatic endometrial stromal sarcoma differs from the properties of SFT.402 Fibrosarcoma and malignant fibrous histiocytoma lack CD34, CD99, and bcl-2 protein, all of which are typically manifest in SFT.

The biologic attributes of SFT have been largely discussed previously. However, some of its characteristics merit reiteration. Approximately 10% of “ordinary” intrathoracic SFTs (lacking histologic indicators of possible malignancy) recur, sometimes massively.373,403 This behavior has most often been linked to incomplete lesional excision at initial surgery, and salvage of the patient is still a distinct possibility if total removal of the tumor (e.g., by extrapleural pneumonectomy)404 can be accomplished.295,297 Metastastic disease is very unusual,405 and it tends to be refractory to oncologic intervention.

Desmoid Tumor

“Desmoid” tumor (DT) is best known as a borderline neoplasm of the deep soft tissues and as a member of the family of fibromatoses.406,407 It can be seen sporadically in patients of virtually any age, but also has a biologic linkage to familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome, in which it is over-represented.408 Wherever it arises in the body, DT pursues a slowly progressive, infiltrative course of growth, eventually impinging on nerves, blood vessels, and other anatomic structures. That property accounts for associated symptoms and signs, which reflect secondary compressive effects of the mass.406

Several examples of DT have been reported as apparently primary pleural neoplasms.409–413 Demographic, radiologic, and clinical findings in such cases are superimposable on those associated with SFT.409,413 Pleural desmoids are deceptively circumscribed in imaging studies, and they typically have a homogeneous radiodensity (Fig. 19-104).

Grossly, DTs of the pleura show a fleshy, uniform, tan-gray cut surface with subtly incorporated bands of internal fibrous tissue (Fig. 19-105). They often appear to have a distinct interface with surrounding tissues, but this attribute is misleading because microscopic study often shows tumor growth beyond the gross boundaries of the lesion.

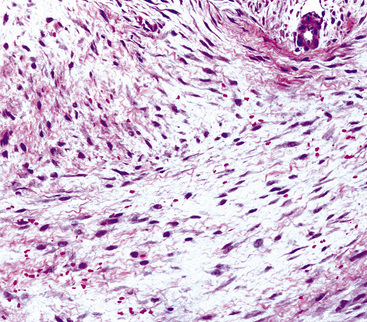

Histologically, the usual appearance of pleural DT is reproducible. It is a hypocellular neoplasm that composes bland fusiform and stellate cells, set in a fibromyxoid stroma (Fig. 19-106). Mitoses are absent or rare; nuclear atypia and necrosis are lacking.406,407 A helpful diagnostic feature is the presence of regularly spaced small blood vessels throughout the lesion; these have open round or oval lumina and relatively thick pericytic cuffs. As mentioned earlier, permeative infiltration of surrounding tissues by the tumor is common.

A potential diagnostic trap is represented by selected examples of DT that have a markedly myxedematous stroma, with or without extravasated erythrocytes (Fig. 19-107). The resulting microscopic image can strongly resemble that of nodular fasciitis, a completely innocuous pseudoneoplastic condition.414 Nodular fasciitis has not been reported in the pleura, however.

Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of DT may show either hypocellular or hypercellular foci, often in juxtaposition.415 The stromal staining characteristics are those of mature collagen. Individual tumor cells are dyshesive and morphologically bland, with tapered ends, fusiform nuclei, dispersed chromatin, and a lack of pleomorphism.

As a derivative of the association between desmoids and familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome, beta-catenin protein is usually dysregulated in DT. Instead of exclusively cytoplasmic immunolocalization of that moiety, it is instead seen as an intranuclear reactant (Fig. 19-108).409,415–417 Unfortunately, an important (if not the principal) differential diagnostic consideration—solitary fibrous tumor—also commonly demonstrates nuclear labeling for beta-catenin.417,418 Hence, one must rely on other immunohistochemical discriminants to separate those two neoplasms. DT is reactive for alpha-isoform and “muscle-specific” actins, and sometimes for desmin, whereas SFT is not.409 Conversely, reactivity for CD34 and CD99 is common in SFT but absent in DT. Diagnostic distinctions among DT, other myofibroblastic proliferations, leiomyomas, and low-grade leiomyosarcomas are not possible at an immunohistochemical level of analysis409,415 and must be made by other means.