Chapter 32 Belt lipectomy/circumferential abdominoplasty

• Presentation of the massive weight loss patient to the plastic surgeon is quite variable.

• Lower truncal excess in the massive weight loss patient is most often circumferential in nature.

• Circumferential dermatolipectomy is usually required to treat the entire lower truncal unit in the massive weight loss patient.

• Photographing the markings and comparing them to the final result is essential in improving technique.

• In a belt lipectomy, the inferior markings anteriorly control final scar location and the superior markings control final scar location posteriorly.

• To avoid dehiscence, the back midline markings should be performed with the patient in a flexed position.

• The anterior resection takes priority over the posterior resection.

• Results and complications correlate with BMI at presentation.

Introduction

Body contouring’s deeply rooted history involves the evolution of specialized surgical techniques to sculpt and reshape the human physique. The concepts of panniculectomy and dermolipectomy were defined at the tail end of the 19th century as pioneers of this craft began to remove pendulous adipocutaneous tissue, resulting in improved functionality.1 In the early 20th century, contour surgery began its transformation from a purely functional modality to an esthetic procedure. As such, Thorek described the first umbilicus preserving abdominoplasty in 1924.2 The 1960s and 1970s saw major advances in this field as techniques involving aponeurotic plication,3 refinement in scar placement3–6 and tissue anchoring utilizing the anatomy of the superficial fascial system7 were made popular. At the turn of the 21st century, the explosive growth and widespread acceptance of bariatric surgery created a new group of patients, collectively referred to as “massive weight loss patients.” New procedures were necessary to excise the redundant tissue in all areas of the body while achieving an esthetic result. The range of contour deformities seen in these patients experienced a dramatic expansion from “anterior only” to “circumferential,” establishing the circumferential dermatolipectomy as a mainstream operation in plastic surgery today.

Disease Process

In general, there are three groups of patients for which a belt lipectomy is beneficial.8 The majority are massive weight loss patients,8 who are not a homogeneous group. Although the pathophysiologic processes are similar and the indications and principles in operative design are comparable, their individual BMI at presentation, fat deposition pattern, and quality of their skin–fat envelope can result in a wide divergence in the nature of their physical deformity. Massive weight loss patients must therefore be well informed regarding the expected body contour outcome to avoid disappointment. Bariatric surgeons tend to emphasize overall weight reduction and often neglect to inform patients that many of the changes in their body habitus are not reversible with weight loss and that normalcy from an esthetic standpoint is often unattainable. The redundant skin with irreversible laxity is almost always circumferential in these patients, resulting in a truncal pattern of an inverted cone.

Diagnosis and Presentation

The characteristic of the skin–fat envelope is a third factor that affects the presentation of massive weight loss patients. The envelope is of major interest to the plastic surgeon and its intrinsic qualities are critical as it influences overall cosmetic outcome. The thickness of the post-weight loss subcutaneous fat tissue is important, as thin layers generally allow for greater pliability and movement of overlying skin, which is important in predicting the final cosmetic result. The authors introduced the concept of “translation of pull” as an excellent predictor of the final results. Prior to surgery, the lateral abdominal tissues are pinched in order to simulate the effect of the lateral abdominal resection on the distal thigh contour (see Fig. 32.1). Thicker nonpliable skin–fat envelopes, which are typical of patients with higher presenting BMIs, have little translation of pull in these areas, indicating that the potential overall improvement in body contour is limited. As a general guideline, the greater the drop in BMI for an individual patient, the greater the “translation of pull.”

Preoperative Preparation

Patient Selection

Patients should be selected for their suitability to undergo circumferential excisional body contouring. Medical, as well as psychiatric, stability is of high importance. Conditions with a documented impact on wound healing such as diabetes, smoking, or connective tissue disorders must be approached with caution as they greatly increase the complication rate. Similarly, the BMI at presentation must be a factor in the plastic surgeon’s decision to operate, as complications are positively correlated with BMI.9 Reasonably, few plastic surgeons agree to operate on patients with a BMI higher than 32. Higher BMIs require surgeon acceptance of increased complication rates, with nearly 100% of patients experiencing some complication with a BMI above 35.

Intraabdominal content is an important determinant of overall abdominal contour. Adequate flattening of the abdominal contour via muscle wall plication is heavily dependent on the amount of intraabdominal content. If excess exists, then the result of a circumferential procedure is similar to that attainable by panniculectomy.10 Therefore, in these situations it would be sensible to limit the procedure to a panniculectomy and avoid the increased risk that accompanies the circumferential excision.

Workup

A careful physical exam should be followed by an evaluation specific to the body contouring procedure. It is important to note the degree of skin laxity, amount of subcutaneous fat tissue and resultant translation of pull in the various areas of interest. Waist definition, the presence of abdominal and/or back rolls, degree of rectus diastasis, presence of hernias, degree of buttock projection and ptosis, degree of anterior and lateral thigh lipodystrophy and ptosis, and the presence of any scars must be additionally noted. Any abdominal scar will alter the anatomy of the subcutaneous fat and the superficial fascial system, which ultimately influences the final contour result. Subcostal scars from gallbladder, gastric, liver, or pancreatic procedures can have a detrimental effect on the vascularity and the viability of the flaps. Additionally, vertical midline scars from previous surgeries may limit the inferior mobility of the abdominal flap. The amount of intraabdominal content must be ascertained as it considerably influences the final cosmetic result. Rather than performing the traditional “diver’s test,” as the surgeon would do in preparation for an abdominoplasty, the authors find it more effective to evaluate the patient’s abdominal contours while in a supine position. The diver’s test is less effective in a massive weight loss patient due to the thickness and laxity of the abdominal wall and subcutaneous fat. If the exam reveals a scaphoid abdominal contour and the abdominal wall falls below the ribcage, then rectus fascia plication during body contouring surgery will likely be effective in flattening the abdomen.11 However, if the abdominal tissues do not fall below the ribcage, then it can be inferred that the intra-abdominal contents are considerable and will blunt the effect of plication in this area.

The altered absorption and dietary manipulation in the massive weight loss patient can create significant abnormalities that must be addressed prior to surgery.12 Exhaustive lab work should be obtained early on in the care of the patient so that ample time exists for correction of any observed abnormalities. The labs should include: CBC, BUN, creatinine, electrolytes, glucose, urinalysis, LFT, iron, calcium, albumin, prealbumin, total protein, vitamin B, magnesium, and thiamine. Chest X-ray and EKG should be obtained as indicated on an individualized basis.

Surgical Plan and Goals

The belt lipectomy is essentially a circumferential wedge excision of the lower trunk with variations in the operative technique.13 On one end of the spectrum exists the “lower body lift type II” as originally described by Lockwood and on the other the “belt lipectomy” as described by the authors, originally in Iowa.8,14,15 Neither procedure is superior to the other and they are instead used to accomplish different operative objectives. We will cover the belt lipectomy here in detail.

Markings

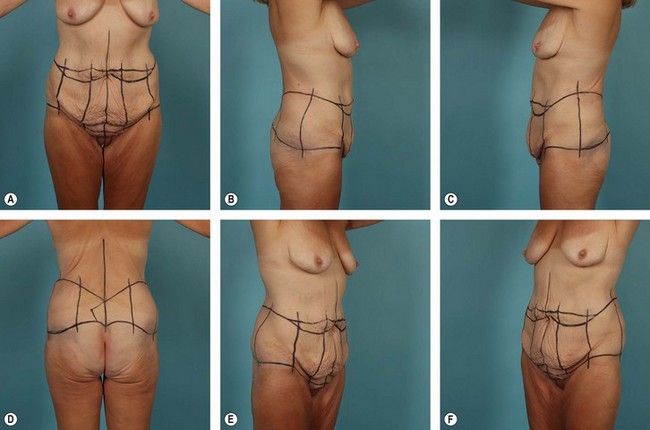

The importance of properly marking the patient prior to a belt lipectomy procedure cannot be overstated. Although there are often adjustments to be made intraoperatively, the majority of the planning and decision making is accomplished through the marking process. This is also a time for the patient and the surgeon to agree on details such as final scar position and for the surgeon to reaffirm previously discussed expectations. Preoperative photographs should assist the surgeon in identifying areas of special concern and potential pitfall. Once the patient has been marked, the surgeon should again photograph the patient. This set of photos in particular can be used for preoperative evaluation and last minute adjustments and also for postoperative comparison at 12 months, allowing the surgeon to critique and improve his or her technique (see Fig. 32.2).

The Superior Back Marking

In contrast to the anterior markings, the superior marks define the final posterior scar position in a belt lipectomy. This is the direct result of greater buttock mobility as compared to the superior back tissues, which have relatively stronger zones of adherence. Therefore, if markings for a belt lipectomy/central body lift are made such that the intended scar is to be just superior to the widest aspect of the pelvic brim, the final scar is most often within 2–3 cm of the superior mark. This concept is unique to the belt lipectomy/central body lift and does not apply if a lower body lift is being performed, as the area of resection is further from the restrictive zones of adherence in the lower back. As a result, the final scar is often more than 3 cm inferior to the superior mark. Therefore, prior to surgery surgeons must evaluate and adjust the position of the posterior superior mark so that the final scar is adequately placed (Fig. 32.2).

Surgical Technique

Anesthesia and DVT Prophylaxis

In the authors’ experience, adequate anesthesia for a belt lipectomy is best attained using a general anesthetic with a thoracic epidural placed preoperatively to aid with postoperative discomfort.16 Early evidence suggests that epidural anesthesia has significant deep vein thrombosis (DVT)/pulmonary embolism (PE) risk reduction; however, its use in plastic surgery remains relatively unstudied. If an epidural is not utilized, then the surgeon must decide whether to add chemoprophylaxis to alternating compression stockings and early ambulation protocols. The ideal chemoprophylaxis regimen has yet to be elucidated.

Step-By-Step Technique

The belt lipectomy procedure as performed by the authors is described here.

Next an incision is made along the inferior abdominal mark and dissection is carried down to, or just deep to, Scarpa’s fascia, and a superior based abdominal flap is elevated. The authors believe that leaving a fatty layer of tissue on the rectus fascia reduces seroma formation along with quilting sutures placed between the abdominal flap and the abdominal wall at closure.17

Complications and Their Management

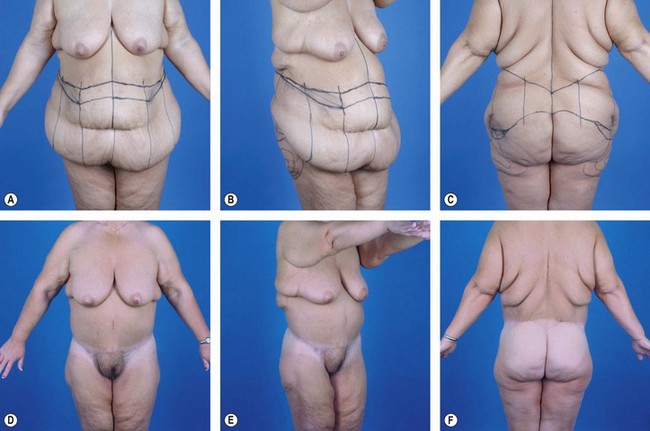

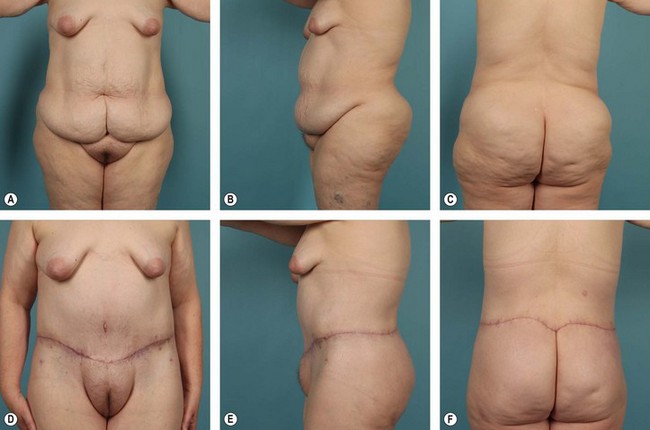

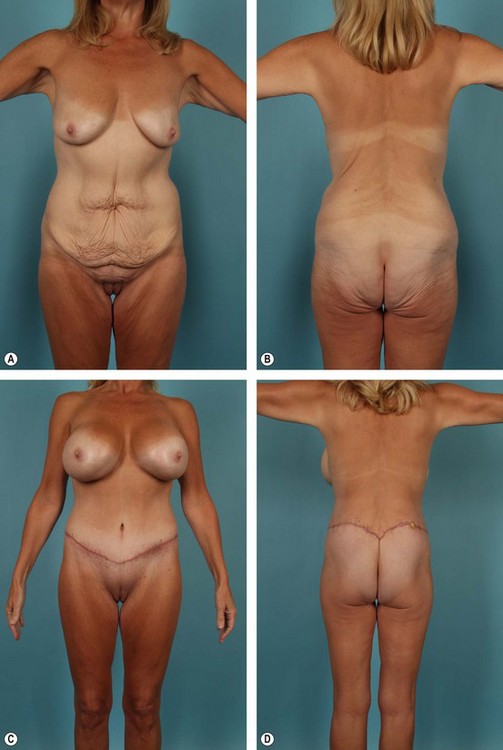

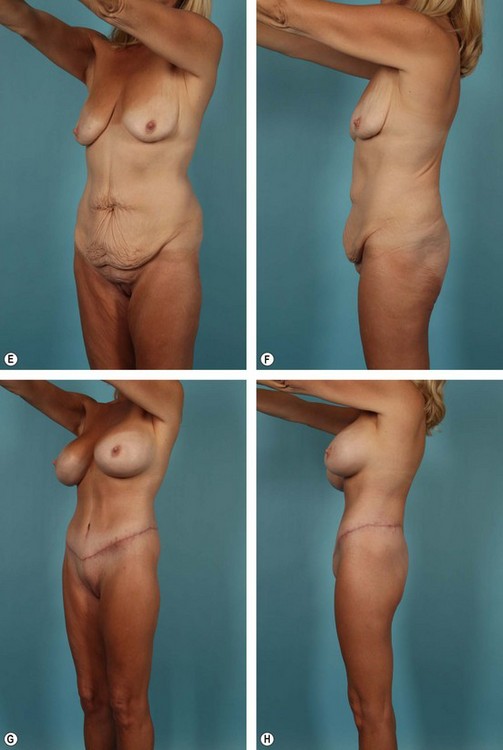

Complications, prognosis, and quality of result after belt lipectomy depend heavily on the patient’s presenting BMI, fat deposition pattern, and quality of the fat/skin envelope. Of these three factors, BMI is the most important. The authors have categorized massive weight loss patients according to presenting BMI as follows: Group I, BMI ≥36; Group II, BMI 30 to 35; Group III, BMI ≤29 (see Figs 32.3–32.5). Although relatively arbitrary, this schema is effective in generating discussion between the patient and the surgeon regarding the expected cosmetic result and potential complications. Group I, for instance, can expect less improvement in overall contour and a higher complication rate after a belt lipectomy than patients in Group II. The comparison is similar between Groups II and III. Within each group, however, BMI is less predictive and does not follow the same logic. Prior to surgery, it is important to explain to patients that although belt lipectomy will significantly improve their contour, their skin quality will remain unchanged. The inexperienced surgeon and the uninformed patient may seek additional tissue excision to address the unchanged skin laxity, which will ultimately lead to disappointment.

1 Kelly HA. Report of gynecological cases (excessive growth of fat). John Hopkins Med J. 1899;10:197.

2 Thorek M, ed. Plastic Reconstruction of the Female Breast and Abdomen Wall. Springfield, IL: Thomas, 1924.

3 Grazer FM. Abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1973;51(6):617–623.

4 Pitanguy I. Trochanteric lipodystrophy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1964;34:280–286.

5 Psillakis J. Abdominoplasty: some ideas to improve results. Aesth Plast Surg. 1978;2:205–215.

6 Regnault P. Abdominoplasty by the W technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1975;55(3):265–274.

7 Lockwood TE. Superficial fascial system (SFS) of the trunk and extremities: a new concept. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87(6):1009–1018.

8 Aly A, Cram AE, Chao BS, et al. Belt lipectomy for circumferential truncal excess: The University of Iowa experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:398.

9 Aly AS, Capella JE. Staging, reoperation and treatment of complications after body contouring in the massive weight loss patient. In: Grotting JC, ed. Reoperative Aesthetic & Reconstructive Plastic Surgery. St. Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 2007:1701.

10 Aly AS. Belt lipectomy. In: Aly AS, ed. Body Contouring after Massive Weight Loss. St. Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 2006:83.

11 Aly AS. Belt lipectomy. In: Aly AS, ed. Body Contouring after Massive Weight Loss. St. Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 2006:86.

12 Sebastian JL. Bariatric surgery and work-up of the massive weight loss patient. Clin Plast Surg. 35(1), 2008.

13 Aly AS. Option in lower truncal surgery. In: Aly AS, ed. Body Contouring after Massive Weight Loss. St. Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 2006:59.

14 Lockwood T. Lower body lift with superficial fascial system suspension. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92:1112.

15 Lockwood T. Lower body lift. Oper Tech Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;3:132.

16 Michaud A-P, Rosenquist RW, Cram AE, Aly AS. An evaluation of epidural analgesia following circumferential belt lipectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(2):538–544.

17 Pollock TA, Pollock H. No-drain abdominoplasty with progressive tension sutures. Clin Plast Surg. 2010;37(3):515–524.