CHAPTER 2 Behavioral Development

A variety of processes are encompassed in growth and development: the formation of tissue; an increase in physical size; the progressive increases in strength and ability to control large and small muscles (gross motor and fine motor development); and the advancement of complexities of thought, problem solving, learning, and verbal skills (cognitive and language development). There is a systematic approach for tracking neurologic development and physical growth in infants, because attainment of milestones is orderly and predictable. However, a wide range exists for normal achievement. The mastering of a particular skill often builds on the achievement of an earlier skill. Delays in one developmental domain may impair development in another (Gessel and Amatruda, 1951). For example, immobility caused by a neuromuscular disorder prevents an infant from exploration of the environment, thus impeding cognitive development. A deficit in one domain might interfere with the ability to assess progress in another area. For example, a child with cerebral palsy who is capable of conceptualizing matching geometric shapes but does not have the gross or fine motor skills necessary to perform the function could erroneously be labeled as developmentally delayed.

Prenatal growth

The most dramatic events in growth and development occur before birth. These changes are overwhelmingly somatic, with the transformation of a single cell into an infant. The first eight weeks of gestation are known as the embryonic period and encompasses the time when the rudiments of all of the major organs are developed. This period denotes a time that the fetus is highly sensitive to teratogens such as alcohol, tobacco, mercury, thalidomide, and antiepileptic drugs. The average embryo weighs 9 g and has a crown-to-rump length of 5 cm. The fetal stage (more than 9 weeks’ gestation) consists of increases in cell number and size and structural remodeling of organ systems (Moore, 1972).

During the third trimester, weight triples and length doubles as body stores of protein, calcium, and fat increase. Low birth weight can result from prematurity, intrauterine growth retardation (small for gestational age, SGA) or both. Large-for-gestational-age (LGA) infants are those whose weight is above the 90th percentile at any gestational age. Deviations from the normal relationship of infant weight gain with increasing gestational age can be multifactorial. Potential causes include maternal diseases (e.g., diabetes, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and seizure disorders), prenatal exposure to toxins (e.g., alcohol, drugs, and tobacco), fetal toxoplasmosis-rubella-cytomegalovirus-herpes simplex-syphilis (TORCHES) infections, genetic abnormalities (e.g., trisomies 13, 18, and 21), fetal congenital malformations (e.g., cardiopulmonary or renal malformations), and maternal malnutrition or placental insufficiency (Kinney and Kumar, 1988).

Postnatal growth

Growth milestones are the most predictable, taking into context each child’s specific genetic and ethnic influences (Johnson and Blasco, 1997). It is essential to plot the child’s growth on gender- and age-appropriate percentile charts. Charts are now available for certain ethnic groups and genetic syndromes such as Trisomy 21 and Turner’s syndrome. Deviation from growth over time across percentiles is of greater significance for a child than a single weight measurement. For example, an infant at the fifth percentile of weight for age may be growing normally, may be failing to grow, or may be recovering from growth failure, depending on the trajectory of the growth curve.

Developmental assessment

Milestones are useful indicators of mental and physical development and possible deviations from normal. It should be emphasized that milestones represent the average for children to attain and that there can be variable rates of mastery that fall into the normal range. An acceptable developmental screening test must be highly sensitive (detect nearly all children with problems); specific (not identify too many children without problems); have content validity, test-retest, and interrater reliability; and be relatively quick and inexpensive to administer. The most widely used developmental screening test is the Denver Developmental Screening Test (DDST), which provides a pass/fail rating in four domains of developmental milestones: gross motor, fine motor, language, and personal-social. The original DDST was criticized for underidentification of children with developmental disabilities, particularity in the area of language. The reissued DDST-II is a better assessment for language delays, which is important because of the strong link between language and overall cognitive development. Table 2-1 lists the prevalence of some common developmental disabilities (Levy and Hyman, 1993).

| Condition | Prevalence per 1000 |

| Cerebral palsy | 2-3 |

| Visual impairment | 0.3-0.6 |

| Hearing impairment | 0.8-2 |

| Mental retardation | 25 |

| Learning disability | 75 |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 150 |

| Behavioral disorders | 60-130 |

| Autism | 9-10 |

Motor development

Primitive Reflexes

The earliest motor neuromaturational markers are primitive reflexes that development during uterine life and generally disappear between the third and sixth months after birth. Newborn movements are largely uncontrolled, with the exception of eye gaze, head turning, and sucking. Development of the infant’s central nervous system involves strengthening of the higher cortical center that gradually takes over function of the primitive reflexes. Postural reflexes replace primitive reflexes between three and six months of age as a result of this development (Schott and Rossor, 2003). These reactions allow children to maintain a stable posture even if they are rapidly moved or jolted (Box 2-1).

Box 2-1 Definitions of Primitive Reflexes

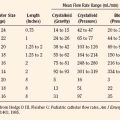

Postural reflexes support control of balance, posture, and movement in a gravity-based environment. The protective equilibrium response can be elicited in a sitting infant by abruptly pushing the infant laterally. The infant will extend the arm on the contralateral side and flex the trunk toward the side of the force to regain the center of gravity (Fig. 2-1). The parachute response develops around 9 months and is a response to a free-fall motion, where the infant extends the extremities in an outward motion to distribute weight over a broader area. Postural reactions are markedly slow in appearance in the infant who has central nervous system damage. Children who fail to gain postural control continue to display traces of primitive reflexes. They also have difficulty with control of movement affecting coordination, fine and gross motor development, and other associated aspects of learning, including reading and writing. Table 2-2 is a list of the average times of appearance and disappearance of the more common primitive reflexes.

| Reflex | Present by (Months) | Gone by (Months) |

| Automatic stepping | Birth | 2 |

| Crossed extension | Birth | 2 |

| Galant | Birth | 2 |

| Moro | Birth | 3-6 |

| Palmar | Birth | 4-6 |

| Asymmetric tonic neck (“fencing”) | 1 | 4-6 |

| Landau | 3 | 12-24 |

| Derotational head righting | 4 | Persists |

| Protective equilibrium | 4-6 | Persists |

| Parachute | 8-9 | Persists |

Gross Motor Skills

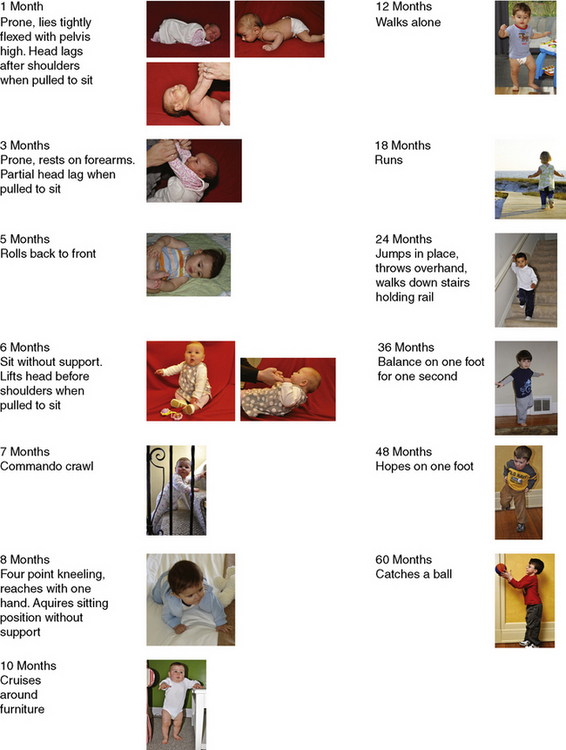

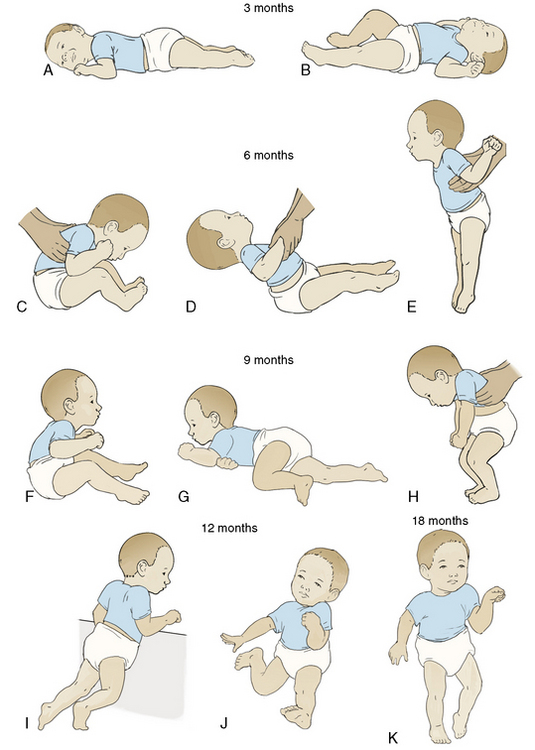

One principle in neuromaturational development during infancy is that it proceeds from cephalad to caudad and proximal to distal. Thus, arm movement comes before leg movement (Feldman, 2007). The upper extremity attains increasing accuracy in reaching, grasping, transferring, and manipulating objects. Gross motor development in the prone position begins with the infant tightly flexing the upper and lower extremities and evolves to hip extension while lifting the head and shoulders from a table surface around 4 to 6 months of age. When pulled to a sitting position, the newborn has significant head lag, whereas the 6-month-old baby, because of development of muscle tone in the neck, raises the head in anticipation of being pulled up.

Rolling movements start from front to back at approximately 4 months of age as the muscles of the lower extremities strengthen. An infant begins to roll from back to front at about 5 months. The abilities to sit unsupported (about 6 months old) and to pivot while sitting (around 9 to 10 month of age) provide increasing opportunities to manipulate several objects at a time (Needleman, 1996). Once thoracolumbar control is achieved and the sitting position mastered, the child focuses motor development on ambulation and more complex skills. Locomotion begins with commando-style crawling, advances to creeping on hands and knees, and eventually reaches pulling to stand around 9 months of age, with further advancement to cruising around furniture or toys. Standing alone and walking independently occur around the first birthday. Advanced motor achievements correlate with increasing myelinization and cerebellum growth. Walking several steps alone has one of the widest ranges for mastery of all of the gross motor milestones and occurs between 9 and 17 months of age. Milestones of gross motor development are presented in Table 2-3 and Figure 2-2. The accomplishment of locomotion not only expands the infant’s exploratory range and offers new opportunities for cognitive and motor growth, but it also increases the potential for physical dangers (Vaughan, 1992).

TABLE 2-3 Cognitive and Language Communication Skills Development

| Average Age of Attainment (Months) | Cognitive | Language Communication |

| 2 | Stares briefly at area when object is removed | Smiles in response to face or voice |

| 4 | Stares at own hand | Monosyllabic babble |

| 8 | Object permanence—uncovers toy after seeing it covered | Inhibits to “no” Follows one-step command with gesture (wave to “come here”) |

| 10 | Separation anxiety from familiar people | Follows one-step command without gesture (“give it to me”) |

| 12 | Egocentric play (pretends to drink from cup) | Speaks first real word |

| 18 | Cause and effect relationships no longer need to be demonstrated to understand (pushes car to move, winds toy on own) Distraction techniques may no longer succeed |

Speaks 20 to 50 words |

| 24 | Mental activity is independent of sensory processing or motor manipulation (sees a child in a book with a mask on face and can later reenact event) | Speaks in two-word sentences |

| 36 | Capable of symbolic thinking | Speaks in three-word sentences |

| 48 | Immature logic is replaced Conventional logic and wisdom |

Speaks in four-word sentences Follows three-step commands |

Most children walk with a mature gait, run steadily, and balance on one foot for 1 second by 3½ years of age. The sequence for additional gross motor development is as follows: running, jumping on two feet, balancing on one foot, hopping, and skipping. Finally, more complex activities such as throwing, catching, and kicking balls, riding bicycles, and climbing on playground equipment are mastered. Development beyond walking incorporates improved balance and coordination and progressive narrowing of additional physical support. Complex motor skills also incorporate advanced cognitive and emotional development that is necessary for interactive play with other children. Figure 2-3 shows the red flags to watch for in the abnormal physical development of the infant.

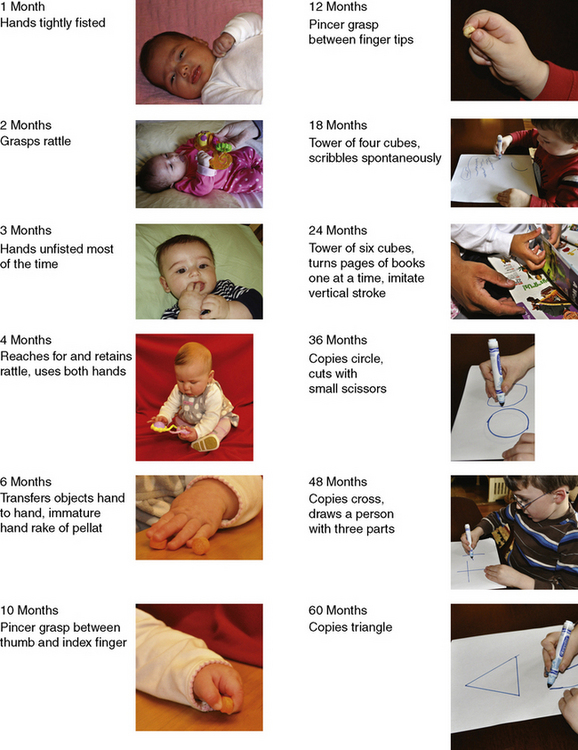

Fine Motor Development

At birth, the neonate’s fingers and thumbs are typically tightly fisted. Normal development moves from the primitive grasp reflex, where the infant reflexively grabs an object but is unable to release it to a voluntary grasp and release of the object. By 2 to 3 months of age the hands are no longer tightly fisted, and the infant begins to bring them toward the mouth, sucking on the digits for self comfort. Objects can be held in either hand by age 3 months and transferred back and forth by 6 months. In early development, the upper extremities assist with balance and mobility. As the sitting position is mastered with improved balance, the hands become more available for manipulation and exploration. The evolution of the pincer grasp is the highlight of fine motor development during the first year. The infant advances from “raking” small objects into the palm to the finer pincer grasp, allowing opposition of the thumb and the index finger, whereby small items are picked up with precision. Children younger than 18 months of age generally use both hands equally well, and true “handedness” is not established until 36 months (Levine et al., 1999). Advancements in fine motor skills continue throughout the preschool years, when the child develops better eye-hand coordination with which to stack objects or reproduce drawings (e.g., crosses, circles, and triangles). Figure 2-4 lists and demonstrates the chronologic order of fine motor development.

Language development

Delays in language development are more common than delays in any other developmental domain (Glascoe, 2000). Language includes receptive and expressive skills. Receptive skills are the ability to understand the language, and expressive skills include the ability to make thoughts, ideas, and desires known to others. Because receptive language precedes expressive language, infants respond to several simple statements such as “no,” “bye-bye,” and “give me” before they are capable of speaking intelligible words. In addition to speech, expression of language can take the forms of gestures, signing, typing, and “body language.” Thus, speech and language are not synonymous. The hearing-impaired child or child with cerebral palsy may have normal receptive language skills and intellect to understand dialogue but needs other forms of expressive language to vocalize responses. Conversely, children may talk but fail to communicate; for example, a child with autism may vocalize by using “parrot talk” or echolalia that has no meaningful content and does not represent language.

Language development can be divided into the three stages of pre-speech, naming, and word combination. Pre-speech is characterized by cooing or babbling until around 8 to 10 months of age, when babbling becomes more complex with multiple syllables. Eventually random vocalization (“da-da”) is interpreted and reinforced by the parents as a real word, and the child begins to repeat it. The naming period (ages 10 to 18 months) is when the infant realizes that people have names and objects have labels. Once the infant’s vocalizations are reinforced as people or things, the infant begins to use them appropriately. At around 12 months of age some infants understand as many as 100 words and can respond to simple commands that are accompanied by gestures. Early into the second year a command without a gesture is understood. Expressive language is slower, and an 18-month-old child has a limited vocabulary of around 25 words. After the realization that words can stand for things, the child’s vocabulary expands at a rapid pace. Preschool language development begins with word combination at 18 to 24 months and is the foundation for later success in school. Vocabulary increases from 50 to 100 words to more than 2000 words during this time. Sentence structure advances from two- and three-word phrases to sentences incorporating all of the major grammatic rules. A simple correlate is that a child should increase the number of words in a sentence with advancing age; e.g., two-word sentences by 2 years of age, three-word sentences by age 3 years (Table 2-3).

Language is a critical barometer of both cognitive and emotional development (Coplan, 1995). Mental retardation may first surface as a concern with delayed speech and language development around 2 years of age; however, the average age of diagnosis is 3 to 4 years. All children whose language development is delayed should undergo audiologic testing. If a child’s expressive skills are advanced compared with his or her receptive skills (e.g., child speaks five-word sentences but does not understand simple commands), a pervasive development disorder could be the cause.

Cognitive development

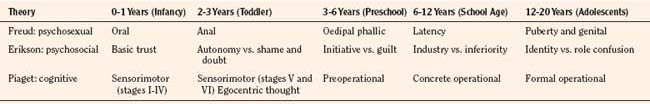

At the core of Freudian theory is the idea of biologically determined drives. The core drive is sexual, broadly defined to include sensations that include excitation or tension and satisfaction or release (Freud, 1952). There are discrete stages: oral, anal, oedipal, latent, and genital. During these stages the focus of the sexual drive shifts with maturation and is at first influenced primarily by the parents and subsequently by an enlarging circle of social contacts. Defense mechanisms in early childhood can develop pathologically to disguise the presence of conflict. The emotional health of the child and adult depends on the resolution of the conflicts that arise throughout these stages.

Erikson’s chief contribution was to recast Freud’s stages in terms of the emerging personality (Erikson, 1963). For example, basic trust, the first of Erickson’s psychosocial stages, develops as infants learn that their urgent needs are met regularly. The consistent availability of a trusted adult creates the conditions for secure attachment. The next stage establishes the child’s internal sense of either autonomy vs. shame and doubt and corresponds to Freud’s anal stage. A sense of either identity or role confusion corresponds to the crisis experienced in Freud’s genital stage (puberty) (Table 2-4).

Piaget’s name is synonymous with the study of cognitive development. A central tenet of his theory is that cognition is qualitatively different at different stages of development (Hobson, 1985). During the sensorimotor stage, children learn basic things about their relationship with their environment. Thoughts about the nature of objects and their relationships are acted out and tied immediately to sensations and manipulation. With the arrival of language the nature of thinking changes dramatically, and symbols increasingly take the place of things and actions. Stages of preoperational thinking, concrete operations, and formal operations correspond to the different ages of preschool, school age, and adolescence, respectively. At all stages, children are not passive recipients of knowledge but actively seek out experience (assimilation) and use them to build on how things work.

Cognitive development and neuromaturational development are closely related, and it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between the two in the infant and child. Early in the neonatal period, cognitive development begins when the infant responds to visual and auditory stimuli by interacting with surroundings to gain information. Activities such as mouthing, shaking, and banging objects provide information to the infant beyond the visual features. Infant exploration begins with the body, with activities such as staring intently at a hand and touching other body parts. These explorations represent an early discovery of “cause and effect,” as the infant learns that voluntary movements generate predictable tactile and visual sensations (e.g., kicking the side of the bed moves a mobile). Signs of abnormal cognitive development are outlined in Box 2-2.

Box 2-2 Abnormal Cognitive Signs

(Modified from Seid M et al.: Perioperative psychosocial interventions for autistic children undergoing ENT surgery, Int J Ped Otorhinolaryngology, 40:107, 1997.)

Erikson (1963) describes the infants’ motivations as dependent on the satisfaction of basic human needs (e.g., food, shelter, and love). According to Freud, the child directs all of his or her energies to the mother and fears her loss because her absence may jeopardize the child’s satisfaction creating tension and anxiety. This dependence is the essence of separation anxiety. Before this stage infants are able to accept surrogates and respond favorably to anyone holding them. Once stranger anxiety develops, active participation of the parents during the hospitalization should be encouraged to maintain a sense of security for the child and promote bonding (Thompson and Standford, 1981).

School-age children, during the “concrete operations” stage, are more independent. Their activities become goal-oriented, and their language skills develop rapidly. They have a sense of conscience and can appreciate feelings of others. Children are able to draw on previous experience and knowledge to formulate predictions about related issues. They have an increased need for explanation and participation. Rather than giving children choices in the operating room (e.g., intravenous injection vs. mask for going to sleep), details about the procedure and options available for the child should be discussed preoperatively in a nonthreatening environment (McGraw, 1994).

Clinical relevance of growth and development in pediatric anesthesia

Down’s Syndrome

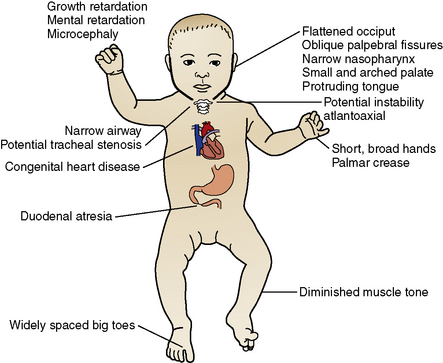

Down’s syndrome is the most common genetic abnormality worldwide, with an estimated prevalence of 1 out of 800 children (Sherman et al., 2007). Although this syndrome was described centuries earlier, Dr. John Langon Down first reported its clinical description in 1866 (Megarbane et al., 2009). Down’s syndrome is the most recognizable and best known chromosomal disorder. The extra copy in chromosome 21 affects several organs and results in a wide spectrum of phenotypical changes (Hartway, 2009). Down’s syndrome is usually identified soon after birth by a characteristic pattern of dysmorphic features (Fig. 2-5) (Ranweiler, 2009). The diagnosis is confirmed by karyotype analysis with trisomy 21 present in 95% of persons with this syndrome (Gardiner and Davisson, 2000).

FIGURE 2-5 The congenital anomalies of Down’s syndrome.

(Modified from Ranweiler R: Assessment and care of the newborn with Down syndrome, Adv Neonatal Care 9:17, 2009; and Santamaria LB, Di Paola C, Mafrica F, et al: Preanesthetic evaluation and assessment of children with Down’s syndrome, The Scientific World Journal 7:242, 2007.)

Perioperative responsibility is shared between the anesthesiologist and the surgeon. The anesthesiologist is responsible for preoperative risk evaluation, perioperative management, and subsequent patient optimization (Hartley et al., 1998). The preoperative evaluation provides the best opportunity to stratify the potential risks, because children with Down’s syndrome often have multiple congenital anomalies, each of which has anesthetic implications (Fig. 2-5) (Santamaria et al., 2007). Important considerations in the operative management of these patients include assessment of their behavioral development, atlantoaxial instability, airway narrowing, and respiratory and cardiac malformations; these are critical issues that require special attention when considering anesthesia (Bhattarai et al., 2008). Wherever possible, preoperative therapeutic interventions must be initiated to reduce the risks associated with these concurrent diseases (Borland et al., 2004). For the anesthesiologist, a system-based approach to the patient with Down’s syndrome may be most useful. For a complete discussion of the anesthetic concerns related to Down’s Syndrome, see Chapter 36, Systemic Disorders.

Behavioral Considerations

Down’s syndrome is the most common cause of mental retardation, which is characterized by developmental delays, language and memory deficits, and other cognitive abnormalities (Roizen and Patterson, 2003). The child’s cognitive state and psychological status often allow the anesthesia provider to ascertain the appropriate technique based on the child’s needs.

Older children and young adults with Down’s syndrome have a higher prevalence of early Alzheimer’s disease, further impairing cognitive function (Nieuwenhuis-Mark, 2009). Interestingly, children up to 6 years of age show age-related gains in adaptive function, but older children show no correlation between age and adaptive function (Dykens et al., 2006). In addition, the incidence of seizure disorders in those with Down’s syndrome is 5% to 10% (Stafstrom et al., 1991).

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a disorder of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity that affects 8% to 12% of children worldwide, with boys overrepresented by a ratio of about 3:1 (Biederman and Faraone, 2005). During child and adolescent development, ADHD is associated with greater risks for low academic achievement, poor school performance, retention in grade level, school suspensions and expulsions, poor peer and family relations, anxiety and depression, aggression, conduct problems, and delinquency (Barkley, 1997). The means of inheritance acquisition is probably multifactorial, but family, twin, and adoption studies have documented a strong genetic basis for ADHD (Thapar et al., 1999). The cellular theory suggests the frontosubcortical cerebellar regions of the brain have inadequate dopamine and noradrenaline to effectively provide inhibitory regulation (Biederman and Faraone, 2005).

Both the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACA) recommend psychoactive medications for children, adolescents, and adults with ADHD. These medications are classified as stimulants or nonstimulants. Perioperative consequences of these medications include resistance to premedication, cardiovascular instability, altered anesthesia requirements (monitored anesthesia care), lower seizure thresholds, and increased postoperative nausea and vomiting (Forsyth et al., 2006).

As an example of medication interaction, one patient required large doses of midazolam while receiving methylphenidate (Ririe et al., 1997). ADHD drugs are associated with increased blood pressure as a result of increased catecholamine levels, but the chronic use of stimulants can deplete these stores or down-regulate catecholamine receptors. Prolonged hypotension has been reported in older patients with ADHD, and cardiac arrest (requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation) during anesthetic induction was reported in a teenager (Bohringer et al., 2000; Perruchoud and Chollett-Rivier, 2008).

Medications such as buproprion are associated with seizures in a dose-related manner. The seizure threshold can be lowered by concomitant administration of drugs such as antipsychotics, antidepressants, systemic steroids, tramadol, and sedating antihistamines. In addition, bupropion inhibits the enzyme responsible for converting tramadol to morphine, thereby reducing the analgesic effect of tramadol (Corner et al., 2002).

These cases highlight the potential difficulties of the drug–drug interactions while a patient is undergoing general anesthesia. Based on these observations, the anesthesiologist should request more details about the medications a patient is taking for ADHD, particularly if they are stimulants or nonstimulants, and the length of time the patient has been taking the medications. As in cardiac arrest, the implications and ramifications of anesthesia can be quite significant (Tables 2-5 and 2-6) (Perruchoud and Chollett-Rivier, 2008).

TABLE 2-5 The Mechanisms of Action of Commonly Used ADHD Medications

| Commonly Used Drug | Mechanism of Action |

| Methylphenidate (Ritalin) | Blocks the reuptake of norepinephrine and dopamine Stimulates the cerebral cortex similarly to amphetamines |

| Dexamphetamine (Dexedrin) | Promotes the release of catecholamines through sympathomimetic amines, primarily dopamine and norepinephrine Competitively inhibits catecholamine reuptake by the presynaptic nerve terminal |

| Buproprion (Wellbutrin) | Inhibits the neuronal uptake of norepinephrine and dopamine |

| Atomoxetine, 25 mg (Strattera) | Selectively inhibits norepinephrine reuptake by the presynaptic nerve terminal |

From Forsyth I et al.: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and anesthesia, Paediatric anaesthesia, 16:371, 2006.

TABLE 2-6 Possible Drug–Drug Interactions with ADHD

| Potential Side Effects | Medications |

| Sympathomimetic drugs that may produce exaggerated cardiovascular effects | Ephedrine, tramadol, SSRIs, MAOIs, tricyclics, herbal remedies, and dietary supplements (e.g., ephedra, St. John’s wort) |

| Stimulants with potential to increase anesthetic requirements | Methylphenidate, dexamphetamine |

| Stimulants with potential to exacerbate seizure activity | Tramadol, detropropoxyphene, SSRIs, tricyclics |

SSRI, Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor.

From Forsyth I et al.: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and anesthesia, Paediatric anaesthesia, 16:371, 2006.

Autism

Autism affects 5 to 7 in 10,000 births, is found in all racial, ethnic, and social backgrounds, and is four times more common in males than females (Rudolph and Rudolph, 2003). Current data suggest that the actual rate is 40 out of 10, 000 births and that one out of every 150 children in the United States is affected (Rutter, 2005). Autism is now recognized a psychiatric childhood disorder, and is listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) under the section of Pervasive Developmental Disorders (PDD). The diagnostic criteria for autistic disorders include qualitative impairments in social interactions, impairment in verbal and nonverbal communications, restricted range of interests, and resistance to change (APA, 2000). These children exhibit hyperactivity and patterns of behavior, activity, and interests that are restrictive, repetitive, and stereotyped.

The etiology is unknown in the vast majority of the cases. However, there is a small minority of patients with notable coexisting medical diseases, including macrocephaly (15% to 35%), seizure disorders (30%), fragile X syndrome (2% to 8%), and tuberous sclerosis (1% to 3%) (Box 2-2) (Bailey and Rutter, 1991; Williams et al., 2008).

Children with autism can present perioperative challenges to a pediatric anesthesia team (van der Walt and Moran, 2001). They are less able to understand the need for the procedures involved in surgery and have difficulty adjusting to the new routine of the hospital visit. Their perioperative anxiety level can be very high, and it may be difficult for them to interact with strangers, even caring and attentive perioperative staff. They are more sensitive to the visual and auditory stimuli of the hospital, particularly in the operating room, and even simple tactile stimuli such as the face mask may overwhelm their senses. Overall, these children are at high risk for severe distress and anxiety; consequently, morbidity and cost may be increased, and patient and parental satisfaction may be decreased.

Premedication varies depending on the requirements of each child, as well as the preferences of the individual anesthesiologist, who might generally use oral, intramuscular, or intravenous medications. Most institutions employ oral midazolam 0.5 mg/kg; however, the side effects are unpredictable and may not allow optimal anesthetic induction (Rainey and van der Walt, 1998). Ketamine is also an effective preoperative sedative, available in intravenous, intramuscular, and oral dosing. Oral ketamine has a 17% bioavailability, compared with 93% when given intramuscularly or intravenously (Clements et al., 1982). An effective transmucosal dosing combines ketamine 3 mg/kg mixed with midazolam 0.5 mg/kg (Funk et al., 2000).

If possible, the patient should undergo conditioning to become familiar with the hospital and the upcoming procedure (Nelson and Amplo, 2009). Diminished waiting time in the preoperative area can lessen fear and stress. Short, clear commands, with empathic positive and negative reinforcements, can help guide the patient through this difficult ordeal. Anesthesia management can be optimized by judicial use of premedication and parental presence during induction. The actual administration of an adequate dose of premedication can be the biggest challenge for the anesthesiologist working with an uncooperative or frightened child with delayed cognitive abilities. A balanced approach can help minimize the use of force, which is sometimes necessary, but nonetheless upsetting to the patient, the family, and the perioperative team. A discussion regarding the potential use of restraints during the perioperative period is imperative to clearly define the caregiver’s expectations regarding this treatment modality. In summary, children with autism can present perioperative challenges, but thoughtful psychosocial and medical interventions can improve patient and parent satisfaction.

For questions and answers on topics in this chapter, go to “Chapter Questions” at www.expertconsult.com.

Association AP, STAT! Ref & Teton Data Systems, 2000. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, ed 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

Bailey A.J., Rutter M.L. Autism. Sci Prog. 1991;75:389.

Barkley R.A. Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: Constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychol Bull. 1997;121:65.

Bhattarai B., Kulkarni A.H., Rao S.T., et al. Anesthetic consideration in Downs syndrome: a review. Nepal Med Coll J. 2008;10:199.

Biederman J., Faraone S.V. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 2005;366:237.

Bohringer C.H., Jahr J.S., Rowell S., et al. Severe hypotension in a patient receiving pemoline during general anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2000;91:1131.

Borland L.M., Colligan J., Brandom B.W. Frequency of anesthesia-related complications in children with Down syndrome under general anesthesia for noncardiac procedures. Paediatr Anaesth. 2004;14:733.

Clements J.A., Nimmo W.S., Grant I.S. Bioavailability, pharmacokinetics, and analgesic activity of ketamine in humans. J Pharm Sci. 1982;71:539.

Coplan J. Normal speech and development: an overview. Pediatr Rev. 1995;16:91.

Corner A.J., Parry M.G. Zyban: Anaesthetic considerations. Anesthesia. 2002;57:96.

Dykens E.M., Hodapp R.M., Evans D.W. Profiles and development of adaptive behavior in children with Down syndrome. Downs Syndr Res Pract. 2006;9:45.

Erikson E.H. Childhood and society, ed 2. New York: WW Norton, 1963.

Feldman H.M. Developmental-behavioral pediatrics. In: Zitelli B.J., Davis H.W., editors. At las of pediatric physical diagnosis. Philadelphia: Mosby, Inc, 2007.

Forsyth I., Bergesio R., Chambers N.A. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and anesthesia. Paediatr Anaesth. 2006;16:371.

Freud A. The role of bodily illness in the mental health of children. In: Eissler R.S., et al, editors. The psychoanalytical study of the child. New York: International University Press, 1952.

Funk W., Jakob W., Riedl T., et al. Oral preanesthetic medication for children: double-blind randomized study of a combination of midazolam and ketamine vs midazolam or ketamine alone. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84:335.

Gardiner K., Davisson M. The sequence of human chromosome 21 and implications for research into Down syndrome. Genome Biol. 1, 2000. REVIEWS0002

Gesell A., Amatruda C.S. Developmental diagnosis. New York, NY: Paul B. Hoeber, Inc, 1951.

Glascoe F.P. Early detection of developmental and behavioral problems. Pediatr Rev. 2000;21:272.

Hartley B., Newton M., Albert A. Down’s syndrome and anaesthesia. Paediatr Anaesth. 1998;8:182.

Hartway S. A parent’s guide to the genetics of Down syndrome. Adv Neonatal Care. 2009;9:27.

Hobson P.R. Piaget: on the ways of knowing in childhood. In: Rutter M., Herson L., editors. Child and adolescent psychiatry: modern approaches. Oxford, England: Blackwell Scientific, 1985.

Johnson C.P., Blasco P.A. Infant growth and development. Pediatr Rev. 1997;18:224.

Kinney J.S., Kumar M.L. Should we expand the TORCH complex? A description of the clinical and diagnostic aspects of selected old and new agents. Clin Perinatol. 1988;15:727.

Levine M.D., Carey W.B., Crocker A.C. Developmental-behavioral pediatrics, ed 3. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1999.

Levy S.E., Hyman S.L. Pediatric assessment of the child with developmental delay. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1993;40:463.

McGraw T. Preparing children for the operating room: psychological issues. Can J Anaesth. 1994;41:1094.

Megarbane A., Ravel A., Mircher C., et al. The 50th anniversary of the discovery of trisomy 21: the past, present, and future of research and treatment of Down syndrome. Genet Med. 2009;11:611.

Moore K.L. Before we are born: basic embryology and birth defects, ed 2. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1972.

Needleman R.D. Growth and development. In: Nelson W.E., editor. Textbook of pediatrics. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1996.

Nelson D., Amplo K. Care of the autistic patient in the perioperative area. AORN J. 2009;8:391.

Nieuwenhuis-Mark R.E. Diagnosing Alzheimer’s dementia in Down syndrome: problems and possible solutions. Res Dev Disabil. 2009;30:827.

Perruchoud C., Chollet-Rivier M. Cardiac arrest during induction of anaesthesia in a child on long-term amphetamine therapy. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100:421.

Rainey L., Van der Walt J.H. The anesthetic management of autistic children. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1998;26:682.

Ranweiler R. Assessment and care of the newborn with Down syndrome. Adv Neonatal Care. 2009;9:17.

Ririe D.G., Ririe K.L., Sethna N.F., et al. Unexpected interaction of methylphenidate (Ritalin) with anesthetic agents. Paediatr Anaesth. 1997;7:69.

Roizen N.J., Patterson D. Down’s syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1281.

Rudolph C.D., Rudolph A.M., STAT! Ref & Teton Data Systems. Rudolph’s pediatrics, ed 21. New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Publication Division, 2003.

Rutter M. Incidence of autism spectrum disorders: changes over time and their meaning. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94:2.

Santamaria L.B., Di Paola C., Mafrica F., et al. Preanesthetic evaluation and assessment of children with Down’s syndrome. The Scientific World Journal. 2007;7:242.

Sherman S.L., Allen E.G., Bean L.H., Freeman S.B. Epidemiology of Down syndrome. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13(3):221-227.

Schott J.M., Rossor M.N. The grasp and other primitive reflexes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2003;74:558.

Shott S.R., Amin R., Chini B., et al. Obstructive sleep apnea: should all children with Down syndrome be tested? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:432.

Stafstrom C.E., Patxot O.F., Gilmore H.E., et al. Seizures in children with Down syndrome: etiology, characteristics and outcome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1991;33:191.

Thapar A., Holmes J., Poulton K., et al. Genetic basis of attention deficit and hyperactivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:105.

Thompson R., Standford G. Child life in hospitals: theory and practice. Charles C Thomas: Springfield, Ill., 1981.

Torfs C.P., Bateson T.F., Curry C.J. Anorectal and esophageal anomalies with Down syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1992;44:847. author reply 848–850

Van der Walt J.H., Moran C. An audit of perioperative management of autistic children. Paediatr Anesth. 2001;11:401.

Vaughan V.C. Assessment of growth and development during infancy and early childhood. Pediatr Rev. 1992;13:8.

Williams C.A., Dagli A., Battaglia A. Genetic disorders associated with macrocephaly. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:2023.