CHAPTER 2 Becoming a Shoulder Arthroplasty Surgeon

Shoulder arthroplasty is much less frequently performed than hip and knee arthroplasty and accounts for only 3.1% of inpatient joint replacements in the United States,1 largely because hip and knee arthrosis is much more common than glenohumeral arthrosis. Additionally, patients with glenohumeral arthrosis tolerate the symptoms better than those with hip and knee arthrosis because they do not rely on their shoulders for locomotion. Consequently, a busy general orthopedic surgeon may easily perform more than 100 hip and knee replacements in a given year and yet see fewer than five patients who are candidates for shoulder replacement during that same period. Moreover, most orthopedic residencies offer the same lower extremity–focused arthroplasty experience. This has been confirmed by our shoulder fellows, most of whom have seen fewer than five total shoulder arthroplasties during a 4-year orthopedic residency.

The desire and necessity to perform shoulder arthroplasty have evolved from advances made in the field of shoulder surgery during the last 2 decades. Shoulder arthroscopy has developed from a solely diagnostic procedure to a part of the surgical armamentarium that allows treatment of nearly every shoulder problem formerly treated by open surgery. As a result, many orthopedists, largely through technique-driven courses, have become proficient at arthroscopic shoulder procedures, including but not limited to rotator cuff and labral repair. As these same surgeons develop a practice in which an increasing number of patients with shoulder problems are treated, it becomes inevitable that they will encounter diagnoses not amenable to arthroscopic treatment, specifically, diagnoses best treated by shoulder arthroplasty. An aging population that is living longer and remaining more active has contributed to the increasing number of shoulder arthroplasties performed annually as well. In the United States alone, 28,742 shoulder arthroplasties were performed in 2003, a 14.4% increase over the previous year.1 This chapter reviews some basic concepts that must be understood when an orthopedic surgeon decides to become a shoulder arthroplasty surgeon.

ANATOMY

Cutaneous

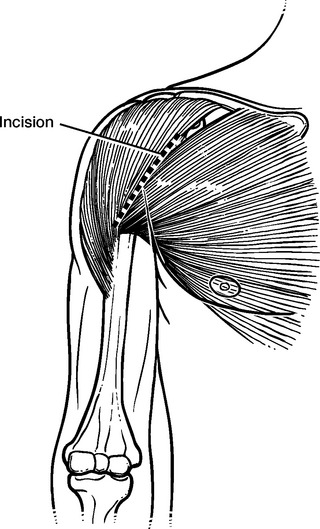

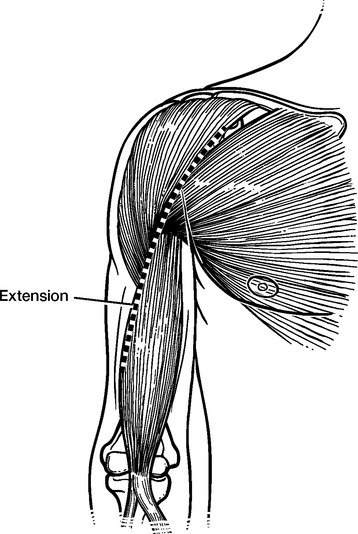

The palpable coracoid process marks the proximal extent of the skin incision for the deltopectoral approach. In thin patients, the deltopectoral interval may be palpable to better assist in directing the skin incision (Fig. 2-1). In revision cases, the skin incision may be extended distally along the lateral aspect of the biceps brachii muscle, which is also palpable (Fig. 2-2).

Subcutaneous

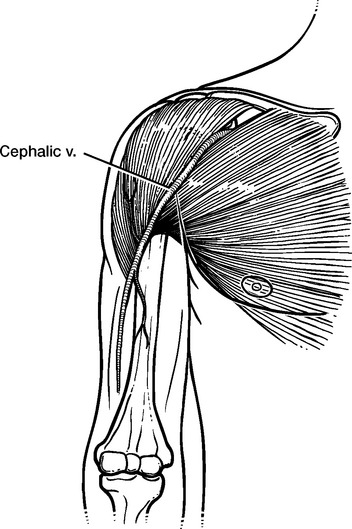

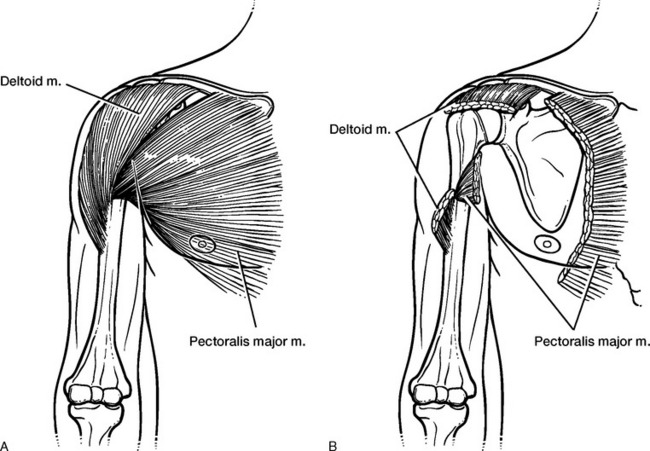

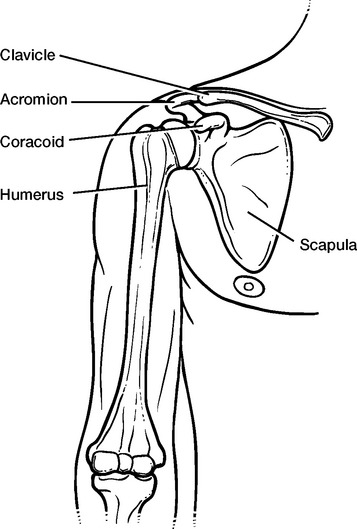

The deltopectoral interval is marked by the cephalic vein. This vein has many small branches, most of which enter the deltoid muscle (Fig. 2-3). The deltoid has attachments at the acromion and the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus. The pectoralis major has attachments at the clavicle, the sternum, and the humerus just lateral to the long head of the biceps brachii tendon (Fig. 2-4).

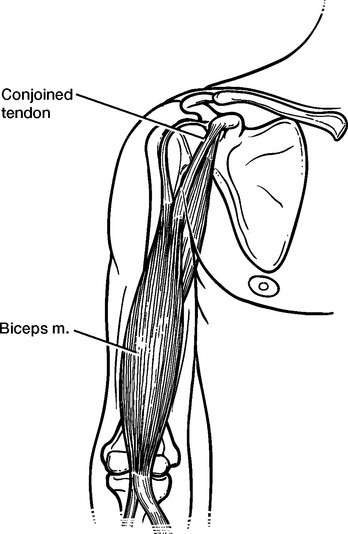

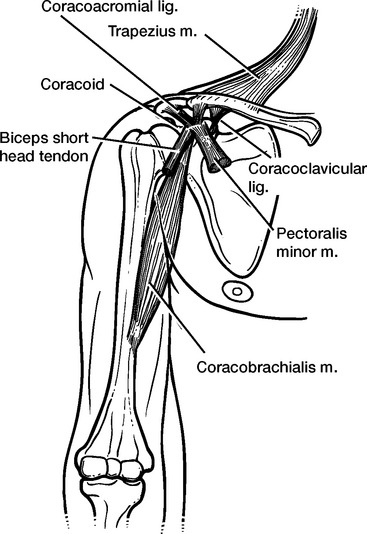

Coracoid/Conjoined Tendon

Immediately deep to the deltoid and pectoralis major muscles is the conjoined tendon of the coracobrachialis and the short head of the biceps brachii (Fig. 2-5). This structure passes from the tip of the coracoid process (the proximal extent of dissection) to the anterior humeral shaft. The coracoid process also serves as the point of attachment of the coracoacromial ligament laterally and the pectoralis minor tendon medially (Fig. 2-6).

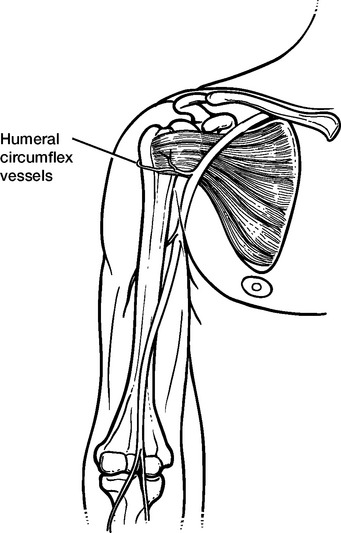

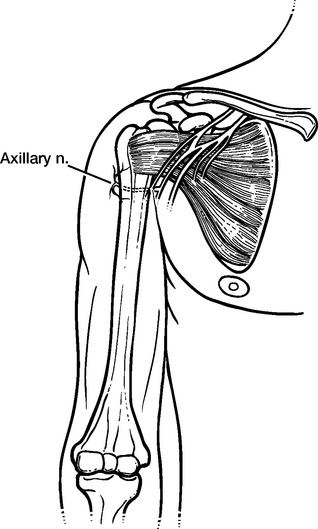

Neurovascular Structures

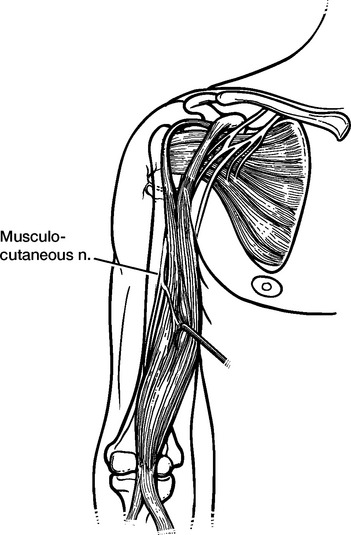

As the conjoined tendon is retracted medially, the anterior humeral circumflex vessels can be seen passing along the inferior border of the subscapularis tendon (Fig. 2-7). The axillary nerve may be visualized inferior to the anterior humeral circumflex vessels during dissection with the arm held in a forward-flexed and slightly internally rotated position (Fig. 2-8). The musculocutaneous nerve may be visualized as it enters the coracobrachialis and the short head of the biceps brachii, although it is not routinely exposed during shoulder arthroplasty (Fig. 2-9).

Subscapularis, Rotator Interval,

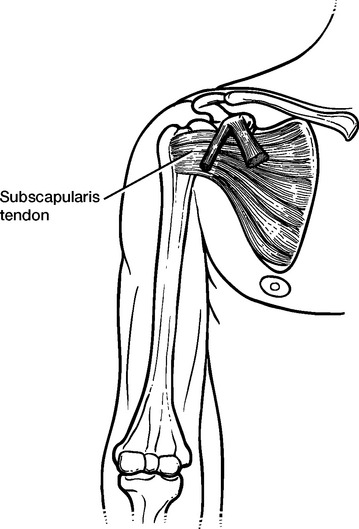

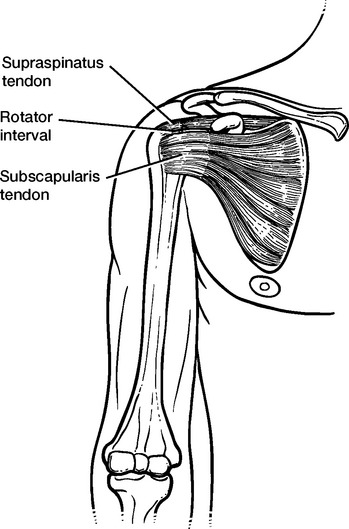

The subscapularis tendon is readily visible just deep to the conjoined tendon as it inserts into the lesser tuberosity of the humerus (Fig. 2-10). The rotator interval is palpable just superior to the subscapularis tendon and is the site for the initial arthrotomy during shoulder arthroplasty (Fig. 2-11). The long head of the biceps brachii exits the bicipital groove of the humerus, traverses the rotator interval, and inserts on the superior glenoid labrum and supraglenoid tubercle.

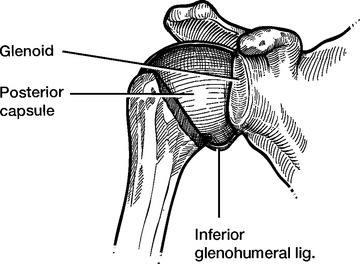

Glenohumeral Ligaments and Capsule

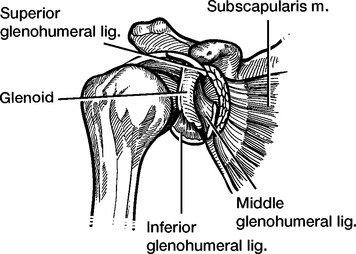

After a subscapularis tenotomy, the superior, middle, and inferior glenohumeral ligaments may be visualized, as well as the inferior joint capsule (Fig. 2-12). The posterior joint capsule is more readily visualized after the humeral head is resected (Fig. 2-13).

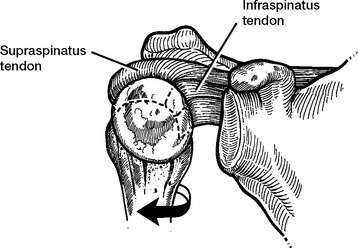

Rotator Cuff

After dislocation of the humeral head, the articular surface of posterior superior rotator cuff is visible. The “bare area” of the humeral head marks the insertion of the infraspinatus, with the supraspinatus inserting superior and anterior to the bare area. The teres minor inserts immediately inferior to the infraspinatus and is not readily distinguishable as a distinct tendon separate from the infraspinatus (Fig. 2-14).

IMPLANTS AND TECHNIQUES

When performing shoulder arthroplasty, it is important to realize that “the shoulder is not the hip.” Although some of the implant research and development pertaining to hip arthroplasty is applicable to the shoulder, much of it is not. Similarly, technical points of paramount importance during hip arthroplasty are inconsequential in shoulder arthroplasty. Although large forces cross the shoulder during activity, the fact that the shoulder is not a weight-bearing joint accounts for many of these differences.

In contrast to hip arthroplasty, the “socket side” of shoulder arthroplasty has most commonly been the site of failure. Although metal-backed acetabular components in hip arthroplasty have been considered an advance, most metal-backed glenoid components have been disappointing in unconstrained total shoulder arthroplasty.

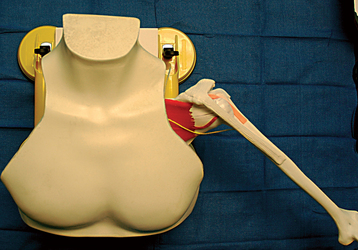

RESOURCES FOR BECOMING A SHOULDER ARTHROPLASTY SURGEON

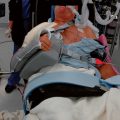

Many resources are available that attempt to teach shoulder arthroplasty, including courses, instructional videos, textbooks, and Internet resources. Educational courses that aim to teach shoulder arthroplasty, both diverse and specific, are frequently offered by organizations such as the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES). Additionally, many of the implant manufacturers offer periodic courses in the use of their implants. Many of these courses provide instruction through lecture and laboratory sessions. Unfortunately, the laboratory sessions of most of these courses provide the surgeon a single opportunity to perform shoulder arthroplasty on a cadaver forequarter or multiple opportunities to perform shoulder arthroplasty on synthetic bones devoid of soft tissue. In our experience, these scenarios are insufficient to adequately teach shoulder arthroplasty. We believe that the best way to learn a skill is by repetition, and performance of a single arthroplasty on a forequarter that is usually poorly held by a metal clamp is suboptimal. We further believe shoulder arthroplasty to be largely a soft tissue operation, thus limiting the usefulness of practice with synthetic bone devoid of soft tissue. To combat these obstacles, in 2004 we began the Joe W. King Invitational Advanced Shoulder Arthroplasty Course. A specially designed shoulder arthroplasty model that includes soft tissues is used to teach by repetition in this course (Fig. 2-16). In addition, after mastering the surgical techniques with the model, each participant performs a shoulder arthroplasty on a full cadaver positioned on an operating table to better replicate reality.

Many textbooks contain sections on shoulder arthroplasty, including multiple-volume general orthopedic textbooks, textbooks focusing on the shoulder, and textbooks limited to shoulder arthroplasty. This textbook, modeled after Shoulder Arthroscopy by Gartsman, was born out of the practical needs we observed while teaching a course in shoulder arthroplasty. This textbook eliminates much of the theoretical discussion of shoulder arthroplasty in favor of providing practi-cal information that actually assists the surgeon in the technical part of the procedure and postoperative care.