CHAPTER 3 BASIC PRINCIPLES

SEDATION

The ideal sedative agent

The ideal sedative agent for use in ICU probably does not exist. All sedative agents cause some degree of cardiovascular instability in critically ill patients. Longer-acting agents can be given by bolus, but may accumulate and do not allow rapid change in response to alterations in a patient’s condition. Shorter-acting agents are often preferred because they can be given by infusion, are less likely to accumulate and allow rapid change in depth, but they can be difficult to titrate.

In general single agents are not effective, either because they fail to achieve all the goals of sedation or because of unacceptable side-effects as the dose is increased. For this reason, it is more common to use a tailored combination of drugs. The principle employed is similar to that of ‘balanced anaesthesia’. By combining the benefits of more than one class of agent, satisfactory levels of sedation can be achieved at much lower doses than could be achieved using either agent alone, thus allowing some of the adverse effects of individual agents to be reduced. A typical combination is that of an opioid (e.g. fentanyl) together with a benzodiazepine (e.g. midazolam). This combination provides analgesia, sedation and anxiolysis. The advantages and disadvantages of these agents are shown in Table 3.1.

TABLE 3.1 Advantages and disadvantages of opioids and benzodiazepines for ICU sedation

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

| Opioids | Respiratory depression Cough suppression Some sedative effects Analgesic |

Nausea and vomiting Delayed gastric emptying and ileus Potential accumulation Respiratory depression Potential cardiovascular instability Withdrawal phenomenon |

| Benzodiazepines | Hypnotic Anxiolytic Amnesia Anticonvulsant |

No analgesic activity Unpredictable duration of action Potential cardiovascular instability Withdrawal phenomenon |

Choice of agents

The choice of agents will depend on local protocols and the clinical condition of the patient. If the balance of a patient’s problem is pain, then analgesia is the main requirement. Epidural anaesthesia, other regional anaesthetic techniques and patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) may be useful. (See Postoperative analgesia, p. 349.) If the balance of the patient’s problem is agitation, then the main requirement may be for sedative or anxiolytic agents. Haloperidol and other major tranquillizers are appropriate for the treatment of delirium and psychosis and recent guidelines have placed greater emphasis on the use of these agents (see Acute confusional states below). Tables 3.2 and 3.3 provide a guide to commonly used analgesic and sedative drugs.

| Drug | Dose | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Morphine | 2–5 mg i.v. bolus 10–50 μg / kg / h |

Cheap, long acting Good analgesic, reasonable sedative Standard agent for PCAS and postoperative pain Metabolized by liver, active metabolites accumulate in renal failure |

| Fentanyl | 2–6 μg / kg / h | Shorter acting than morphine Good analgesic less sedative Metabolized by liver No active metabolites No accumulation in renal failure |

| Alfentanil | 20–50 μg / kg / h | Shorter acting than fentanyl Good analgesic, less sedative No active metabolites, no accumulation in renal failure Rapid termination of effects after discontinuation |

| Remifentanil | 0.1–0.25 μg / kg / min | Ultrashort-acting analgesic, very titratable Metabolized by plasma esterases Rapid clearance even after prolonged infusion Mostly used intra-operatively or for short-term ventilation Causes significant bradycardia and hypotension; avoid boluses |

TABLE 3.3 Commonly used sedative agents (doses based on 70 kg adult)

| Drug | Dose | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Diazepam | 5–10 mg bolus i.v. | Cheap, long-acting benzodiazepine Reasonable cardiovascular stability Sedative, amnesic, anticonvulsant actions Given by intermittent boluses. Metabolized in liver. Long elimination half-life. Active drug and active metabolites can accumulate in sicker patients, therefore avoid continuous infusions |

| Midazolam | 2–5 mg bolus i.v., 2–10 mg / h | Similar properties to diazepam but shorter acting Metabolized by the liver Can be given by continuous infusion |

| Etomidate | 0.2 mg / kg bolus i.v. | Short acting cardiovascular stable anaesthetic induction agent Used only as single bolus dose for induction of anaesthesia, e.g. prior to intubation. Associated with significant adrenal suppression Not to be used by infusion |

| Propofol | 1–3 mg / kg bolus, i.v., 2–5 mg / kg / h | Short-acting intravenous anaesthetic agent Sedative, anticonvulsant and amnesic properties Used for induction of anaesthesia and intubation May cause significant hypotension Avoid infusions in children |

Propofol is perhaps one of the most widely used sedative agents in adult ICU. Bolus doses of 1–3 mg / kg are sufficient to induce anaesthesia (e.g. prior to intubation). Smaller doses of 10–20 mg repeated to effect may be useful for increasing the depth of sedation, e.g. prior to suction or painful procedures.

There have been ongoing reports of inhaled anaesthetic agents being used for sedation in critical care. These may be of value in specific circumstances. Isoflurane and other volatile agents may be useful in asthma and severe bronchospasm because of their bronchodilator properties. Specific systems for delivering volatile agents into ventilator circuits on the ICU have been developed. Nitrous oxide may be of value for changes of burns dressings, but should not be used for more than 12 h because of bone marrow suppression.

Problems associated with over-sedation

Sedation scoring

Sedation scoring systems may be useful in helping titrate levels of sedation. A typical score (performed hourly) together with appropriate responses is shown in Table 3.4.

| Description | Score | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Agitated and restless Awake and uncomfortable |

+3 +2 |

Levels +3 to +2: inadequate sedation. Give bolus of sedative / analgesic drugs and increase infusion rates |

| Awake but comfortable Roused by voice |

+1 0 |

Levels +1 to 0 appropriate levels of sedation. Reassess regularly |

| Roused by touch Roused by painful stimuli Unrousable |

−1 −2 −3 |

Level −1 to −3 excessive level of sedation Reduce or stop infusion of sedative/analgesic drugs Restart when desired level attained |

| Natural sleep | A | Ideal |

| Paralysed | P | Difficult to assess level of sedation. Consider physiological response to stimulation |

COMMON PROBLEMS RELATED TO SEDATION

Patient who is difficult to sedate

Exclude possible causes of agitation, including: full bladder, painful wounds, hypoxia, hypercarbia, and endotracheal tube touching carina.

Exclude possible causes of agitation, including: full bladder, painful wounds, hypoxia, hypercarbia, and endotracheal tube touching carina. Review other drug therapy and stop where appropriate. Many drugs (for example H2 blockers) have the potential to induce confusional states.

Review other drug therapy and stop where appropriate. Many drugs (for example H2 blockers) have the potential to induce confusional states. Consider tracheostomy or nasal intubation. These are often better tolerated, and allow sedative and analgesic drugs to be significantly reduced.

Consider tracheostomy or nasal intubation. These are often better tolerated, and allow sedative and analgesic drugs to be significantly reduced.Patient who is slow to wake up

If a patient fails to regain full consciousness after sedative and analgesic drugs have been stopped for a period of time, the question invariably arises as to ‘why?’ This may be due to the accumulation of drugs or their active metabolites, which resolves with time, but other causes of coma or ‘apparent coma’ should be excluded. Consider:

Severe muscle weakness is common following critical illness so it may not be immediately apparent that the patient is actually awake, but unable to move. A similar clinical picture may also be seen in the presence of pontine lesions (e.g. following central pontine myelinolysis or brainstem stroke). Careful clinical examination is required to ascertain the true clinical picture. An EEG and CT scan may be helpful. If no other cause of coma can be established and failure to wake up is considered to result from the accumulation of sedative agents, a trial of naloxone or flumazenil may occasionally be diagnostic (Table 3.5). This is not without risk, however, and may precipitate convulsions. Seek senior advice.

| Drug | Dose | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Naloxone | 0.4–2 mg bolus i.v. | Competitive antagonist of opioid receptors* Used to reverse sedation and respiratory depression caused by opioids |

| Flumazenil | 0.2–0.5 mg bolus i.v. | Competitive antagonist of benzodiazepine receptors* Used to reverse sedation and respiratory depression caused by benzodiazepines |

Withdrawal phenomena / acute confusional states

When drugs used before admission, or sedative drugs given in ICU are stopped, drug withdrawal states may develop. This may result in seizures, hallucinations, delirium tremens, confusional states, agitation and aggression. Elderly patients are particularly susceptible. These phenomena are difficult to control without further heavy sedation, but usually settle over time. You should look for and treat any reversible causes of confusion (Box 3.1).

Box 3.1 Causes of acute confusional states

Side-effects of prescribed drugs

Withdrawal of alcohol or other centrally acting drugs

Renal and hepatic encephalopathy

Brain injury (e.g. stroke, cerebral haemorrhage)

Endocrine abnormalities (e.g. use of steroids, thyroid abnormalities)

Drugs that can be useful for the control of acute confusional states, including those induced by the withdrawal of mixed sedative agents, are shown in Table 3.6. You should generally seek senior advice before resorting to these agents.

TABLE 3.6 Drugs for the treatment of acute confusional states

| Drug | Dose | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lorazepam | 1–3 mg bolus i.v. | Long acting benzodiazepine Useful for controlling seizures and withdrawal phenomenon |

| Clonidine | 50–150 μg bolus i.v. | α2 agonist Useful for controlling withdrawal phenomenon See previous notes |

| Chlorpromazine | 5–10 mg bolus i.v. Repeat as necessary |

Major tranquillizer* Useful in acute confusional states |

| Haloperidol | 5–10 mg bolus Repeat as necessary |

Major tranquillizer* Useful in acute confusional states |

MUSCLE RELAXANTS

‘Awareness’, when paralysed patients are inadequately sedated during unpleasant procedures. Although well described in the context of inadequate anaesthesia during surgical procedures in the operating theatre this is a real risk in the ICU. Assisted ventilation, tracheal intubation, suctioning, and other invasive procedures can all be very uncomfortable or painful and frightening for a patient. Increasing numbers of surgical procedures, such as tracheostomy, are also performed in ICU!

‘Awareness’, when paralysed patients are inadequately sedated during unpleasant procedures. Although well described in the context of inadequate anaesthesia during surgical procedures in the operating theatre this is a real risk in the ICU. Assisted ventilation, tracheal intubation, suctioning, and other invasive procedures can all be very uncomfortable or painful and frightening for a patient. Increasing numbers of surgical procedures, such as tracheostomy, are also performed in ICU! Potential for rapid development of severe or fatal hypoxia following accidental unnoticed disconnection of the ventilator, because the paralysed patient cannot make any respiratory effort.

Potential for rapid development of severe or fatal hypoxia following accidental unnoticed disconnection of the ventilator, because the paralysed patient cannot make any respiratory effort. Potential for neuromyopathy, which is common in patients with multiple organ failure and may be associated with the prolonged use of muscle relaxants.

Potential for neuromyopathy, which is common in patients with multiple organ failure and may be associated with the prolonged use of muscle relaxants.Therefore, the use of relaxants should be restricted to the following:

The management of patients with acute brain injury or cerebral oedema (e.g. to prevent rise in ICP on coughing).

The management of patients with acute brain injury or cerebral oedema (e.g. to prevent rise in ICP on coughing). The management of patients with critical cardiovascular or respiratory insufficiency where the balance between oxygen delivery and oxygen consumption may be improved by preventing muscle activity.

The management of patients with critical cardiovascular or respiratory insufficiency where the balance between oxygen delivery and oxygen consumption may be improved by preventing muscle activity.The choice of drugs depends upon the clinical situation and the patient’s general condition.

Suxamethonium

Only used by bolus injection for endotracheal intubation, 1 mg / kg i.v. bolus.

This is a short-acting depolarizing muscle relaxant, which gives good intubating conditions in less than a minute. It is useful for rapidly intubating patients in an emergency and has the advantage for the inexperienced that it has a short duration of action (2–4 min), so that if intubation is difficult, spontaneous respiratory effort is rapidly re-established. In a small number of patients, however, the effects are prolonged because of a genetic abnormality in the cholinesterase enzyme, which breaks down suxamethonium.

Side-effects associated with the use of suxamethonium include bradycardia, hypotension, and increased salivation and bronchial secretions. These can be blocked by the use of atropine. Intraocular pressure and intracranial pressure are transiently increased. All patients suffer a small increase (0.5–1 mmol / L) in serum potassium following suxamethonium. The drug should therefore be avoided in patients with hyperkalaemia. In some groups of patients, this increase in potassium may be much greater and may result in a cardiac arrest. It is also best avoided in all patients with pre-existing neuromuscular disease. Contraindications to the use of suxamethonium are shown in Box 3.2.

| Absolute | Relative |

|---|---|

| Recent (significant) burns or crush injuries Spinal injury (after first 24 h) Renal failure and raised K+ Myasthenia gravis Dystrophia myotonica History of previous allergy History of malignant hyperpyrexia |

Severe overwhelming sepsis Prolonged immobility Neuromyopathies (including critical illness neuropathy) |

If it is necessary to use a muscle relaxant for intubation, as an alternative to suxamethonium, non-depolarizing muscle relaxants (see below) can be used as part of a ‘modified rapid sequence induction’. Any non-depolarizing muscle relaxant could theoretically be used at relatively high dose for this purpose. Rocuronium, however, has the fastest onset of action. Moreover, a specific antagonist to rocuronium is now available, so the effects may be rapidly reversed if intubation proves difficult. (See Practical procedures, p. 398.)

NON-DEPOLARIZING MUSCLE RELAXANTS

Currently available non-depolarizing muscle relaxants are slower in onset and have a longer duration of action than suxamethonium. They can be used for intubation as an alternative to suxamethonium (when this is contraindicated), or when the risk of airway contamination with gastric contents is low. Non-depolarizing muscle relaxants can be used either by intermittent bolus or infusion, to provide continuous muscle relaxation when this is required. Table 3.7 provides a guide to commonly used agents.

| Drug | Dose | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Atracurium | 0.5 mg / kg i.v. bolus 0.5–1.0 mg / kg / h infusion |

Onset 1–2 min, duration 30 min Undergoes spontaneous degradation, no accumulation in hepatorenal failure. Ideal for use by infusion Localized histamine release common May cause bronchospasm |

| Cisatracurium | 150 μg / kg i.v. bolus 1–3 μg / kg / min infusion |

Onset 1–2 min, duration 45 min Similar to atracurium, less histamine release |

| Vecuronium | 0.1 mg / kg i.v. bolus 0.05–0.2 mg / kg / h infusion |

Onset 1–2 min, duration 40 min Can be associated with bradycardia Parent drug and active metabolites can accumulate in hepatorenal failure |

| Rocuronium | 600 μg / kg i.v. bolus 300–600 μg / kg / h infusion |

Faster onset of action than vecuronium More prolonged block Similar in other aspects to vecuronium Higher frequency of allergic reactions |

| Pancuronium | 0.1 mg / kg i.v. bolus | Onset 2 min, duration 1 h Produces tachycardia and increased blood pressure Relatively long-acting usually given by intermittent bolus Can accumulate in renal failure |

Monitoring neuromuscular blockade

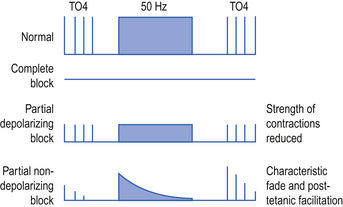

The use of muscle relaxants should be regularly reviewed and consideration given to stopping them intermittently to assess the adequacy of sedation. Neuromuscular blockade can be monitored if required using nerve stimulators. On the ICU this is most commonly required to exclude residual muscle paralysis, for example prior to performing brainstem death tests. An electric current is passed through a peripheral nerve and the response of the muscle supplied by that nerve observed. A common method of assessment is to produce four impulses, 0.5 s apart, known as a train of four (TO4), followed by a period of continuous tetanic stimulation at 50 Hz and then another train of four. Typical responses are shown in Figure 3.1.

Reversal of neuromuscular blocking drugs

In the majority of cases in ICU the effects of muscle relaxant drugs are allowed to wear off over time. Occasionally it may be appropriate to reverse the action of non-depolarizing drugs. This can usually be achieved with anticholinesterase drugs once there is some evidence of recovery of muscle function as demonstrated by the presence of two or three twitches on TO4.

A new drug, sugammadex, has recently become available that selectively binds and inactivates rocuronium and vecuronium, but not other non-steroid structure muscle relaxant drugs. This can rapidly reverse the effects of rocuronium (and to a lesser extent vecuronium and possibly pancuronium) even when only just administered.

PSYCHOLOGICAL CARE OF PATIENTS

Communication difficulties

Communication difficulties following tracheal intubation have not been adequately resolved. Written messages and letter boards are cumbersome, and lip reading is often difficult. Speaking aids for ventilated patients are available in the form of an artificial larynx to produce tones, but none is satisfactory for acute use as they take time and practice to work well. Speaking tracheostomy tubes or tracheostomy tube cuff deflation may be helpful in the recovery phase of illness.

Pain, fear and anxiety

Many patients in intensive care will have painful surgical wounds and many will also have stiff painful limbs and joints as a result of immobility and critical illness neuropathy (see p. 304). Almost all will be subjected to repeated, potentially painful, procedures. Patients may be aware how sick they are, or even that they are dying. The overall experience is very frightening.

Take time to get to know patients. Acknowledge their fears and anxieties. Give appropriate explanations and reassurance.

Take time to get to know patients. Acknowledge their fears and anxieties. Give appropriate explanations and reassurance. Avoid disturbing the patient at night if possible. Encourage daytime stimulation in the form of visits from relatives and children, television and radio, all of which improve morale.

Avoid disturbing the patient at night if possible. Encourage daytime stimulation in the form of visits from relatives and children, television and radio, all of which improve morale.One of the roles of the intensive care follow-up clinic is to facilitate better recognition and earlier, more appropriate management of the late psychological sequelae of intensive care, including post-traumatic stress disorder. (See ICU follow-up clinics, p. 15.)

FLUIDS AND ELECTROLYTES

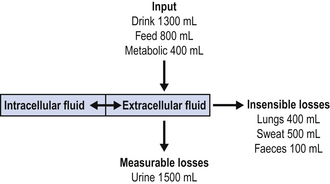

The management of fluid and electrolyte balance in critically ill patients is fundamental to intensive care. In health, daily input and output are in balance and the figures are approximately as shown in Figure 3.2. This translates to daily water and electrolyte requirements as shown in Table 3.8.

| Water | 30–35 mL / kg / day |

| Na+ | 1–1.5 mmol / kg / day |

| K+ | 1 mmol / kg / day |

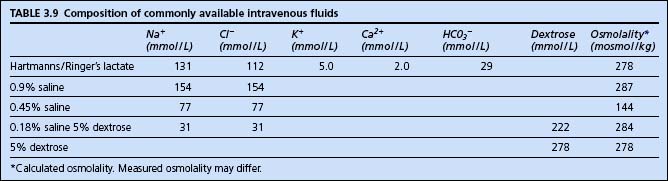

Simplistically therefore, fluid management is a matter of selecting an appropriate fluid and volume to provide the required amount of water and electrolytes. The constituents of commonly available fluids are shown in Table 3.9.

Daily requirements could, for example therefore, be provided by 2–3 L of 4% dextrose and 0.18% saline, with 20 mmol of potassium added to each litre. For the critically ill patient on the intensive care unit, however, the situation is more complex than this, with a number of factors often simultaneously affecting fluid and electrolyte balance.

Factors potentially reducing fluid requirements

Factors potentially increasing fluid requirements

Widespread capillary leak associated with sepsis and inflammatory conditions may result in redistribution of body water out of the vascular compartment, and the development of pulmonary, central and peripheral oedema.

Widespread capillary leak associated with sepsis and inflammatory conditions may result in redistribution of body water out of the vascular compartment, and the development of pulmonary, central and peripheral oedema.Factors affecting electrolyte requirements

At cellular level: hypoxia, acidosis, toxins and the effects of drugs can interfere with ionic pump mechanisms and lead to alterations in normal electrolyte balances and requirements.

At cellular level: hypoxia, acidosis, toxins and the effects of drugs can interfere with ionic pump mechanisms and lead to alterations in normal electrolyte balances and requirements.In addition, the underlying condition, repeated venesection and multiple procedures may lead to the need for repeated blood transfusions. Significant coagulopathy may require use of other blood products such as fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and platelet concentrates. There is frequently a requirement for multiple drug infusions. All these factors and additional volumes of fluid need to be taken into account when managing fluid and electrolyte balance.

Practical fluid management

Measure 24-h fluid balance accurately. The nurses will usually record the totals of all fluids, in and out, hourly. This will include all intravenous and nasogastric fluids, all drugs and all measurable losses. (It does not include unmeasurable insensible losses or shifts between intra- and extravascular spaces.)

Measure 24-h fluid balance accurately. The nurses will usually record the totals of all fluids, in and out, hourly. This will include all intravenous and nasogastric fluids, all drugs and all measurable losses. (It does not include unmeasurable insensible losses or shifts between intra- and extravascular spaces.) Measure serum electrolytes frequently. Sodium (Na+) and potassium (K+) at least every 4–6 h in sicker patients. Magnesium (Mg2+), calcium (Ca2+) and phosphate (PO43−) daily or as required. Increasing Na+ and urea suggest dehydration.

Measure serum electrolytes frequently. Sodium (Na+) and potassium (K+) at least every 4–6 h in sicker patients. Magnesium (Mg2+), calcium (Ca2+) and phosphate (PO43−) daily or as required. Increasing Na+ and urea suggest dehydration. Additional measurements such as plasma and urinary osmolality and urinary electrolytes are useful in difficult cases. (See Oliguria, p. 188.)

Additional measurements such as plasma and urinary osmolality and urinary electrolytes are useful in difficult cases. (See Oliguria, p. 188.)A typical fluid regimen for a 70 kg adult patient not receiving nutritional support, and with normal renal function, is shown in Table 3.10.

TABLE 3.10 Typical fluid management in 70 kg adult with normal renal function

| Maintenance | Dextrose 4% and saline 0.18% 20–60 mmol / K+ / L | 80–100 mL / h |

| Additional losses | 0.9% saline 20 mmol / K+ / L | Replace nasogastric and drain losses mL for mL |

| Other electrolytes | K+, Ca2+, Mg2+ | As required |

| Colloids | Gelatin /starch | As required to maintain adequate circulating volume |

| Blood products | Red cells / FFP / platelets | As indicated |

Measurement of patients’ weight as a means to aiding fluid management has never proved to be that useful due to difficulties in accurate measurement. In addition, progressive loss of lean body mass and fat in the immobilized critically ill patient over time make baseline measurements unrepresentative of ideal weight.

Disturbances of fluid and electrolyte balance are discussed further in Chapter 8.

NUTRITION

During the acute phase of illness, intensive care patients are often catabolic. Muscle is broken down to provide amino acids for energy requirements and for synthesis of acute phase proteins. Nitrogen from protein breakdown is lost in the urine and patients develop a negative nitrogen balance. This may result in severe muscle wasting and weakness, greatly prolonging recovery. The aim of feeding patients is therefore to provide adequate amino acids and energy to minimize this process.

Although there is a very large literature on nutrition in the critically ill patient, there are relatively few practice guidelines. NICE has published a set of guidelines on nutrition for patients in hospital, but these only briefly mention intensive care. A fuller set of guidelines has been produced by the Intensive Care Society, together with guidelines from the Canadian Critical Care Network and the European Society For Enteral and Parenteral Nutrition. The web sites of these organizations can be consulted for further information (Critical care nutrition http://www.criticalcarenutrition.com, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) 2006 Nutrition in adults. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG032NICEguideline.pdf).

Nutrition can be provided by the enteral or parenteral route depending upon the circumstances, although the enteral route is preferred wherever possible (see below). Whichever route is chosen, the aim is to provide all the patient’s nutritional requirements. Typical daily nutritional requirements are given in Table 3.11. (See also Fluids and electrolytes, p. 49.)

| Item | Requirement / kg / day | Typical daily requirement (70 kg adult) |

|---|---|---|

| Maintenance fluid | 30–35 mL / kg / day | 2500 mL |

| Na+ | 1–1.5 mmol / kg / day | 100 mmol |

| K+ | 1 mmol / kg / day | 60–80 mmol |

| Phosphate | 0.5 mmol / kg / day | <50 mmol |

| Energy | 30–40 kcal / kg / day* | 2500 kcal |

* Increased in critical illness. See below.

Estimation of energy requirements

Energy requirements depend on body mass and metabolic rate. They are normally 30–40 kcal / kg / day, but this may be increased in critical illness. In most instances when starting nutritional support it is not necessary to calculate exact energy requirements. Standard feeds can be used and the energy content can be adjusted subsequently if necessary. If required, energy requirements can be estimated using formulae such as the one in Table 3.12, or measured with a metabolic computer attached to the breathing circuit (these measure O2 uptake and CO2 production to derive energy consumption). Longer term requirements should be assessed by a dietician.

| Step 1. Estimate basal metabolic rate (kcal / day) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Male | Female |

| 15–18 | BMR = 17.6 × weight (kg) + 656 | BMR = 13.3 × weight (kg) + 690 |

| 18–30 | BMR = 15.0 × weight (kg) + 690 | BMR = 14.8 × weight (kg) + 485 |

| 30–60 | BMR = 11.4 × weight (kg) + 870 | BMR = 8.1 × weight (kg) + 842 |

| >60 | BMR = 11.7 × weight (kg) + 585 | BMR = 9.0 × weight (kg) + 656 |

| Step 2. Add factor for level of activity | ||

| Bed bound / immobile | Add 10% | |

| Bed bound mobile / sitting | Add 15–20% | |

| Mobile | Add 25% | |

| Step 3. Adjust for critical illness | ||

| Burns 25–90% (1st month) | Add 20–70% | |

| Severe sepsis/multiple trauma | Add 20–50% | |

| Persistent increase temperature 2°C | Add 25% | |

| Burns 10–25% (1st month) Multiple long bone fractures (1st week) |

Add 10–30% | |

| Persistent increase temperature 1°C | Add 12% | |

| Burns 10% (1st month) Single fracture (1st week) Postoperative patient (1st 4 days) Inflammatory bowel disease Mild infection |

Add 0–10% | |

| Partial starvation (>10% loss body weight) | Subtract 0–10% | |

An alternative method of estimating energy requirements is indirect calorimetry. Metabolic computers are available which sample the patient’s inspired and expired gases and, using an assumed value for the respiratory quotient, can estimate total energy expenditure.

Energy requirements are generally provided as a mixture of carbohydrate and fats.

Vitamins, minerals and trace elements

Vitamins, minerals and trace elements are essential for health and many have important roles in enzyme pathways. Less is known, however, about the requirements during critical illness. Both water- and fat-soluble vitamins can be provided by commercially available preparations. Folic acid and vitamin B12 should be prescribed separately. Trace elements and minerals, including calcium, magnesium, iron, zinc, copper, selenium, molybdenum, manganese and chromium, are available. Replacement is guided by the reference values for daily recommended intake and signs of deficiency. All patients with chronic alcohol dependency should receive vitamin B supplements (see p. 241).

Immunonutrition

There has been a lot of interest over the last 10 years in the role of several specific nutrients in modulating the immune response. Arginine, glutamine, nucleotides and omega-3 fatty acids have been studied, either alone or in combination, in a variety of patient groups. Studies have shown conflicting results, To date, there is no definitive evidence that immunonutrition improves outcome in critically ill patients.

ENTERAL FEEDING

Route of administration

Delayed gastric emptying is a major factor limiting the success of enteral feeding. There is increasing use of feeding tubes placed through the pylorus, which deliver enteral feed directly into the duodenum or jejunum. Although it is possible to place these tubes ‘blindly’, more commonly placement is guided by X-ray screening, ultrasound or endoscopy. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) or gastrojejunostomy (PEGJ) is useful in patients who are likely to require long-term feeding. This can be performed on the ICU and has the advantage that it allows all nasogastric tubes to be removed, reducing the risks of nosocomial chest infections.

Complications

The potential complications of enteral feeding are shown in Box 3.3.

Box 3.3 Complications of enteral feeding

Tube malposition or displacement

Regurgitation and pulmonary aspiration

Increased risk of nosocomial infection associated with NG tubes

Misplacement or dislodgement of the NG tube can result in accidental delivery and / or aspiration of feed into the lungs. The position of the tube must always be verified before feed or drugs are administered (see Passing a nasogastric tube, p. 421). Blocked NG tubes can occasionally be ‘rescued’ by flushing with normal saline using a syringe. Small syringes are more effective then large ones for this purpose.

COMMON PROBLEMS ASSOCIATED WITH ENTERAL FEEDING

Diarrhoea

Do not immediately stop enteral feed. Discuss, with the dietician changing the feed, reduction in the osmolality and increase in the fibre content.

Do not immediately stop enteral feed. Discuss, with the dietician changing the feed, reduction in the osmolality and increase in the fibre content. Perform a rectal examination to exclude faecal impaction (common in the elderly), which may be a cause of overflow diarrhoea. Consider suppositories or manual evacuation.

Perform a rectal examination to exclude faecal impaction (common in the elderly), which may be a cause of overflow diarrhoea. Consider suppositories or manual evacuation. Confirm diarrhoea is not infective in nature: send stool specimens for microscopy and culture (Salmonella, Shigella and Campylobacter species) and for Clostridium difficile toxin.

Confirm diarrhoea is not infective in nature: send stool specimens for microscopy and culture (Salmonella, Shigella and Campylobacter species) and for Clostridium difficile toxin. Treat any infective process appropriately. For Clostridium difficile use oral or nasogastric metronidazole or vancomycin.

Treat any infective process appropriately. For Clostridium difficile use oral or nasogastric metronidazole or vancomycin. Review the drug chart. Stop any prokinetic drugs such as metoclopramide. If the diarrhoea is non-infective, consider the use of loperamide.

Review the drug chart. Stop any prokinetic drugs such as metoclopramide. If the diarrhoea is non-infective, consider the use of loperamide.PARENTERAL NUTRITION

Practical TPN

Most units now use one or two standard mixture feeds, prepared under sterile conditions in the pharmacy or bought in from an outside supplier. The typical composition of a standard feed is shown in Table 3.13.

| Volume | 2.5 L |

| Nitrogen source (9–14 g nitrogen) | L-amino acid solution |

| Energy source (1500–2000 kcal) | Glucose and lipid emulsion |

| Additives | Electrolytes, trace elements, vitamins |

| Other additives | Insulin and H2 blockers may be added if required |

Some patients need regimens specifically tailored to their needs. For example, patients in renal failure, who are not on renal support, require a reduced volume and restricted nitrogen intake to avoid rises in plasma urea. For most patients, however, a standard feed can be started and advice subsequently sought from dieticians, pharmacists or a parenteral nutrition team. In practice therefore, decide what volume of feed the patient will tolerate. Standard adult feeds are usually 2.5 L a day, but smaller volume feeds are available for fluid-restricted patients.

Monitoring during TPN

Glucose. Blood sugar will often rise and require the addition of an insulin infusion. Recent evidence suggests that close control of blood sugar levels may improve outcome of critically ill patients (see p. 215).

Glucose. Blood sugar will often rise and require the addition of an insulin infusion. Recent evidence suggests that close control of blood sugar levels may improve outcome of critically ill patients (see p. 215). Adequate energy requirements. Judged by degree of catabolism clinically. Nitrogen balance can be calculated but in practice rarely is.

Adequate energy requirements. Judged by degree of catabolism clinically. Nitrogen balance can be calculated but in practice rarely is.Complications

The complications of TPN include all complications of central venous access (see Complications of central venous cannulation, p. 376). Metabolic derangement, particularly hyper- or hypoglycaemia, hypophosphataemia and hypercalcaemia, are common and require appropriate adjustment of the feed. Hepatobiliary dysfunction, including elevation of hepatic enzymes, jaundice and fatty infiltration of the liver, may occur. This is usually caused by a combination of the patient’s underlying disease processes and overfeeding. Reduce the volume of TPN and / or energy content. If the serum becomes very lipaemic, it may be necessary to reduce the fat content.

STRESS ULCER PROPHYLAXIS

It was previously thought that sucralfate, which is relatively effective in preventing gastrointestinal bleeding was preferable to ranitidine for prophylaxis against gastric erosion. The rationale for this, was that while sucralfate provides an effective mucosal barrier it does not suppress gastric acid production. Agents such as ranitidine that do suppress gastric acid production are associated with increased gastric pH, which may lead to bacterial overgrowth in the stomach and the potential for an increase in nosocomial pneumonias. Recent evidence, however, suggests that ranitidine is substantially more effective at preventing gastrointestinal haemorrhage than sucralfate, and that there is little difference in the incidence of nosocomial pneumonia. On this basis, sucralfate has largely disappeared from intensive care practice in the United Kingdom.

DVT PROPHYLAXIS

Patients requiring intensive care are at risk for the development of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). Risk factors include immobility, venous stasis, poor circulation, major surgery, malignancy and pre-existing illness. Over and above these well-known factors, intensive care itself is an independent risk factor. Upper limb venous thrombosis is more common in ITU than in other settings, usually due to thrombosis following subclavian vein catheterization. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) with associated venous thrombosis is probably more common than previously realized (see p. 263).

Despite all these risk factors, there has been surprisingly little research performed to document either the true incidence of DVT or PE in such a population or what constitutes the best form of prophylaxis. Guidance on prophylaxis has, however, recently been published by the Intensive Care Society (Venous thromboprophylaxis in critical care 2008, see www.ics.ac.uk). The use of compression stockings and early mobilization of patients may help to reduce the risk. Once coagulation profiles are within normal ranges prophylactic low-dose subcutaneous heparin is usually given. Low molecular weight heparins are usually preferred, for example,

Many junior doctors routinely use suxamethonium, as it is one of the ‘first’ muscle relaxants introduced during anaesthetic training. However, while it is appropriate for use by junior trainees in anaesthetic practice because of a favourable risk–benefit ratio, this is not necessarily the case in critically ill patients. Suxamethonium should not be used ‘routinely’ and the risk versus benefits should be carefully considered for each individual patient.

Many junior doctors routinely use suxamethonium, as it is one of the ‘first’ muscle relaxants introduced during anaesthetic training. However, while it is appropriate for use by junior trainees in anaesthetic practice because of a favourable risk–benefit ratio, this is not necessarily the case in critically ill patients. Suxamethonium should not be used ‘routinely’ and the risk versus benefits should be carefully considered for each individual patient.

While adequate energy intake might prevent negative nitrogen balance (muscle breakdown) in a critically ill patient, excess feeding will not produce a positive nitrogen balance in a catabolic patient. This will only be achieved in the recovery phase of illness. Therefore avoid excessive feeding. Seek specialist advice from a dietician.

While adequate energy intake might prevent negative nitrogen balance (muscle breakdown) in a critically ill patient, excess feeding will not produce a positive nitrogen balance in a catabolic patient. This will only be achieved in the recovery phase of illness. Therefore avoid excessive feeding. Seek specialist advice from a dietician.

The absence of bowel sounds alone in a ventilated patient without other evidence of ileus should not prevent attempts to commence enteral feeding.

The absence of bowel sounds alone in a ventilated patient without other evidence of ileus should not prevent attempts to commence enteral feeding.

To prevent inadvertent administration of enteral drugs/feed by the i.v. route (and vice versa) many units now use a separate colour-coded (typically purple) syringe system for enteral administration. The Luer lock on these syringes, and the enetral feeding systems to which they connect, is reversed, making them incompatible with IV ports.

To prevent inadvertent administration of enteral drugs/feed by the i.v. route (and vice versa) many units now use a separate colour-coded (typically purple) syringe system for enteral administration. The Luer lock on these syringes, and the enetral feeding systems to which they connect, is reversed, making them incompatible with IV ports.