Basic dermatological surgery

The demand for the removal of benign and malignant skin lesions has increased considerably, such that skin surgery is now practised by many general practitioners as well as by dermatologists. Knowledge of basic surgical techniques is mandatory for all those who treat skin disease.

Instruments and methods

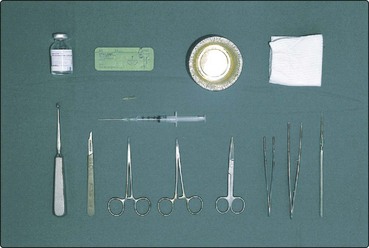

The basic instruments (Fig. 1) include a #3 scalpel handle and #15 blade, a toothed Adson’s forceps, a small smooth-jawed needle holder, a pair of fine scissors, artery forceps and a Gillies skin hook. Curettes and skin punches come in various sizes. A solution of 1% lidocaine (Xylocaine) with 1/200 000 adrenaline (epinephrine) is usually satisfactory as the local anaesthetic, but plain lidocaine must be used on the fingers, toes and penis. The maximum safe dose for an 80-kg person using 1% lidocaine and adrenaline (1/200 000) is 40–50 mL. This volume is significantly reduced if higher concentrations of lidocaine or no adrenaline are used. The skin is prepared (but not sterilized) using, for example, 0.05% aqueous chlorhexidine (Unisept). Alcohol-based preparations are avoided as, if cautery is used, the solution may ignite. Sterile towels, placed around the operation site, reduce the chance of infection.

Basic surgical techniques

Excisional biopsy

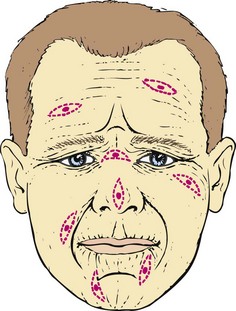

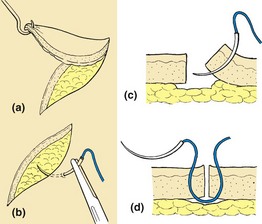

An excisional biopsy is planned after considering the local anatomy. The excision’s axis depends on the skin creases (Fig. 2) and its margin on the nature of the lesion. The ellipse to be excised is drawn on the skin using a marker pen. An ellipse has an apical angle of about 30° and is usually three times as long as it is wide. If any shorter, ‘dog-ears’ appear at either end, although these can easily be corrected. After cleaning, local anaesthetic is infiltrated using a fine needle into the area of the lesion. Once numbed, the skin is incised vertically down to fat with the scalpel, in a smooth continuous manner to complete both arcs of the ellipse. The ellipse is freed from surrounding skin, secured at one end with a skin hook and removed from the underlying fat, usually using the scalpel blade (Fig. 3). In most cases, the wound can now be repaired, although any bleeding vessels will need to be stemmed with cautery, hyfrecation or suturing.

In a simple interrupted skin suture, the needle is inserted vertically through the skin surface down through the dermis and up the other side of the incision to trace a flask-shaped profile (see Fig. 3). The wound is apposed and slightly everted. Stitches should not be tied too tightly. Nylon or polypropylene sutures are tied with three knots in alternating directions to produce a square knot. Care is exercised at sites where keloids may form (e.g. the upper back, chest or jawline), where scars may be obvious (e.g. the face of a young woman) and when healing may be poor (e.g. the lower leg). In cosmetically sensitive sites, running subcuticular stitches are preferable.

Incisional, punch and shave biopsies

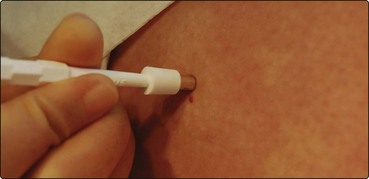

An incisional biopsy is done for diagnostic purposes. The technique is similar to an excision except that less tissue is taken. A punch biopsy is a sharp circular blade, which is twisted and gently pushed into the skin to create a vertical cylindrical defect (normally 4 mm in diameter) and is used for removing small lesions or for diagnostic biopsies (Fig. 4).

Curettage

Curettage is performed for seborrhoeic warts, pyogenic granulomas or single viral warts (e.g. on the face), but not for naevi or possibly malignant lesions. Basal cell carcinomas can be treated by repeated cycles of curettage and cautery but careful case selection is required. After being anaesthetized, the lesion is removed by a gentle scooping motion with the curette spoon or ring (Fig. 5), and then the base is cauterized. Curettings should be sent for histological analysis in 10% formalin.

Other surgical techniques

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy using liquid nitrogen is effective for viral warts, molluscum contagiosum, seborrhoeic warts, actinic keratoses, in situ squamous cell carcinoma and, in some instances, biopsy-proven basal cell carcinoma. The liquid nitrogen (at −196°C) is delivered by spray gun (e.g. Cry-Ac) or cotton wool bud and injures cells by ice formation. After immersion in a flask containing liquid nitrogen, a cotton wool bud on a stick is applied to the lesion for about 10 s until a thin frozen halo appears at the base. The spray gun is used from a distance of about 10 mm for a similar length of freeze (Fig. 6). Longer freeze times are given for suitable malignant lesions. Blisters may develop within 24 h. They are punctured and a dry dressing applied. Side-effects include hypopigmentation of pigmented skin and ulceration of lower leg lesions (not recommended in this site), particularly in the elderly. Treatment is repeated after 4 weeks if necessary.

Basic dermatological surgery

Skin surgery is best performed in an operating theatre with aseptic technique, adequate lighting and trained nurses.

Skin surgery is best performed in an operating theatre with aseptic technique, adequate lighting and trained nurses.

Local anaesthetic: 1% lidocaine with 1/200 000 adrenaline (epinephrine) is an adequate local anaesthetic for most sites.

Local anaesthetic: 1% lidocaine with 1/200 000 adrenaline (epinephrine) is an adequate local anaesthetic for most sites.

Nylon or polypropylene sutures should be used. Smallest diameter sutures are used on the face.

Nylon or polypropylene sutures should be used. Smallest diameter sutures are used on the face.

Histopathology is performed on all biopsy material, which needs to be labelled carefully.

Histopathology is performed on all biopsy material, which needs to be labelled carefully.

Excisions are done as an ellipse, parallel to the crease marks, and are about three times as long as wide, with 30° angles at the ends.

Excisions are done as an ellipse, parallel to the crease marks, and are about three times as long as wide, with 30° angles at the ends.

Shave biopsy is a technique suitable for the removal of benign naevi.

Shave biopsy is a technique suitable for the removal of benign naevi.

Punch biopsy is a useful technique for removing small lesions or for full-thickness diagnostic biopsy.

Punch biopsy is a useful technique for removing small lesions or for full-thickness diagnostic biopsy.

Curettage is a good treatment for seborrhoeic warts, single viral warts and pyogenic granulomas.

Curettage is a good treatment for seborrhoeic warts, single viral warts and pyogenic granulomas.

Cautery, e.g. hyfrecation, secures haemostasis and destroys tissue.

Cautery, e.g. hyfrecation, secures haemostasis and destroys tissue.

Cryotherapy is used for viral and seborrhoeic warts, premalignant conditions and some tumours.

Cryotherapy is used for viral and seborrhoeic warts, premalignant conditions and some tumours.