Basic clinical skills in gynaecology

History

Menstrual history

The time of onset of the first period, the menarche, commonly occurs at 12 years of age and can be considered to be abnormally delayed over 16 years or abnormally early at 9 years. The absence of menstruation in a girl with otherwise normal development by the age of 16 is known as primary amenorrhoea. The term should be distinguished from the pubarche, which is the onset of the first signs of sexual maturation. Characteristically, the development of breasts and nipple enlargement predates the onset of menstruation by approximately 2 years (see Chapter 16).

Examination

Breast examination

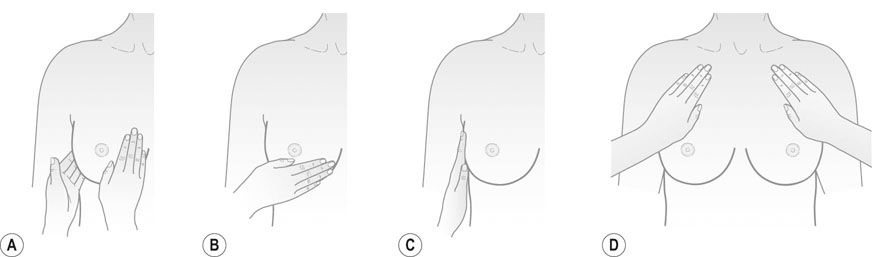

Breast examination should be performed if there are symptoms or at the first consultation in women over the age of 45 years. The presence of the secretion of milk at times not associated with pregnancy, known as, galactorrhoea may indicate abnormal endocrine status. Systematic palpation with the flat of the hand should be undertaken to exclude the presence of any lumps in the breast or axillae (Fig. 15.1).

Examination of the abdomen

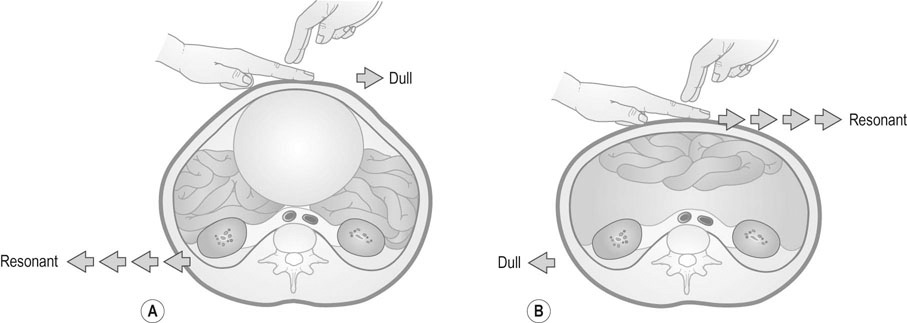

Inspection of the abdomen may reveal the presence of a mass. The distribution of body hair should be noted, and the presence of scars, striae and hernias. Palpation of the abdomen should take account of any guarding and rebound tenderness. It is important to ask the patient to outline the site and radiation of any pain in the abdomen, and palpation for enlargement of the liver, spleen and kidneys should be carried out. If there is a mass, try to determine if it is fixed or mobile, smooth or regular, and if it arises from the pelvis (you should not be able to palpate the lower edge above the pubic bone). Check the hernial orifices and feel for any enlarged lymph nodes in the groin. Percussion of the abdomen may be used to outline the limits of a tumour, to detect the presence of a full bladder or to recognize the presence of tympanitic loops of bowel. Free fluid in the peritoneal cavity will be recognized by the presence of dullness to percussion in the flanks and resonance over the central abdomen (Fig. 15.2).

Pelvic examination

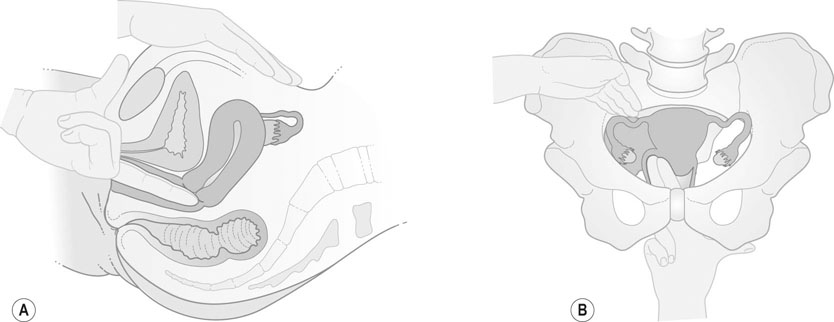

The patient should be examined resting supine with the knees drawn up and separated or in stirrups in the lithotomy position (Fig. 15.3). Gloves should be worn on both hands during vaginal and speculum examinations.

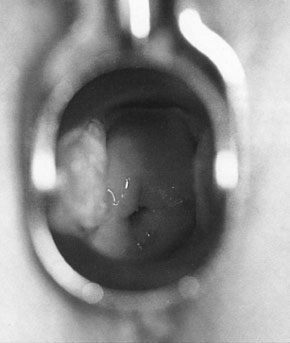

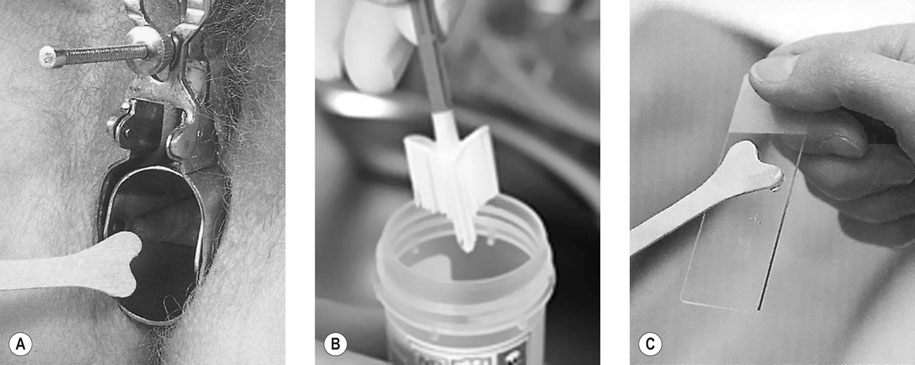

Holding the lips of the labia minora open with the left hand, insert the speculum into the introitus with the widest part dimension of the instrument in the transverse position as the vagina is widest in this direction. When the speculum reaches the top of the vagina gently open the blades and visualize the cervix (Fig. 15.4). Make a note of the presence of any discharge or bleeding from the cervix and of any polyps or areas of ulceration. Remember that the appearance of the cervix is changed after childbirth with the external os more irregular and slit like.

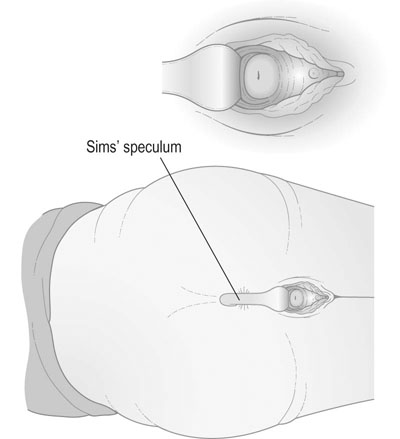

Where vaginal wall prolapse is suspected, a Sims’ speculum should be used, as it provides a clearer view of the vaginal walls. Where the Sims’ speculum is used, it is preferable to examine the patient in the semiprone or Sims’ position (Fig. 15.5).

Bimanual examination

Bimanual examination is performed by introducing the middle finger of the examining hand into the vaginal introitus and applying pressure towards the rectum (Fig. 15.7). As the introitus opens, the index finger is introduced as well. The cervix is palpated and has the consistency of the cartilage of the tip of the nose. It must be remembered that the abdominal hand is used to compress the pelvic organs on to the examining vaginal hand. The size, shape, consistency and position of the uterus must be noted. The uterus is commonly pre-axial or anteverted, but will be postaxial or retroverted in some 10% of women. Provided the retroverted uterus is mobile, the position is rarely significant. It is important to feel in the pouch of Douglas for the presence of thickening or nodules, and then to palpate laterally in both fornices for the presence of any ovarian or tubal masses. An attempt should be made to differentiate between adnexal and uterine masses, although this is often not possible. For example, a pedunculated fibroid may mimic an ovarian tumour, whereas a solid ovarian tumour, if adherent to the uterus, may be impossible to distinguish from a uterine fibroid. The ovaries may be palpable in the normal pelvis if the patient is thin, but the Fallopian tubes are only palpable if they are significantly enlarged.

In a child or in a woman with an intact hymen, speculum and pelvic examination is usually not performed unless as part of an examination under anaesthesia. It should always be remembered that a rough or painful examination rarely produces any useful information and, in certain situations such as tubal ectopic pregnancy, may be dangerous. Throughout the examination remain alert to verbal and non-verbal indications of distress from the patient. Any request that the examination be discontinued should be respected (Box 15.1).

Presenting your findings

Unless you are asked only to discuss one particular part of the examination always start by commenting on the patient’s general condition including pulse and blood pressure. For abdominal examination, list the findings on inspection first followed by those on palpation and percussion (if there is abdominal distension or a mass). If there is a mass arising from the pelvis describe it in terms of a pregnant uterus, e.g. a mass reaching the umbilicus would be a 20 week size pelvic mass. If there are areas of tenderness specify whether they are associated with signs of peritonism (guarding and rebound). On pelvic examination, describe the findings on inspection of the vulva and then of the cervix (if a speculum examination was carried out). Describe the size, position and mobility of the uterus and any tenderness. Finally, say whether there were any palpable masses or tenderness in the adnexae.