Chapter 4 Basic Approach to Ultrasound of Other Structures in the Extremities

Cystic or Partially Cystic Soft-Tissue Masses

Simple Cyst

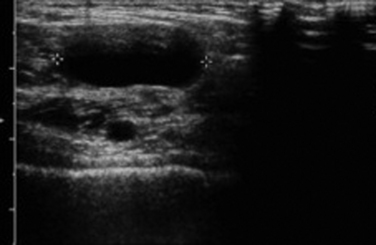

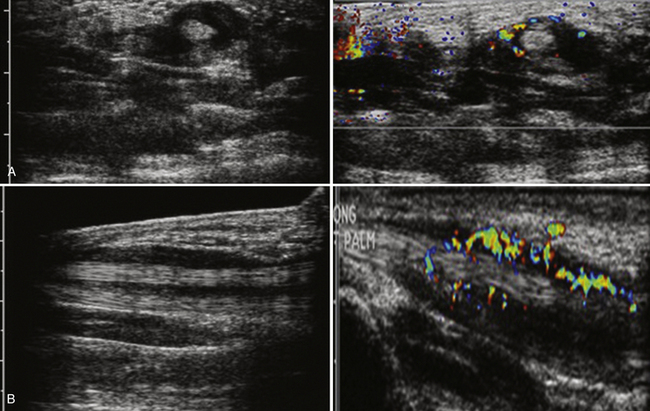

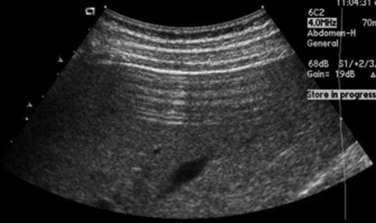

A simple cyst must have all of the following: (1) anechoic, (2) thin or barely perceptible wall, (3) posterior acoustic enhancement, and (4) no evidence of flow on color Doppler evaluation.1 If a mass has all of these features, it can confidently be called benign by the imager. Unfortunately, in the extremities, pure simple cysts are rare (as opposed to within the kidneys or liver, for example). These rules, however, are still applicable and appropriate for describing the features of cystic masses and make a good framework for a report and communication. Expert technique with the use of the appropriate frequency transducer, careful observation and analysis, and documentation of these findings are necessary to prevent errors that might falsely reassure a referring physician or lead to a failure in recognition of significant findings (Fig. 4.1).

Abscess, Cellulitis, and Foreign Body

One of the more unexpected findings for the peripheral nerve ultrasonographer can be an occult abscess. Patients who have these are often referred for limb pain and may have focal tenderness and erythema. Although systemic septicemia can hematogenously seed the soft tissues and set up the necessary components for an abscess, these patients frequently have a history of prior instrumentation (i.e., biopsy or surgery) or trauma at the site of the abscess.2,3 Careful examination to exclude the presence of a foreign body is critical because this can change management. Even without the presence of cellulitis or abscess, the most sensitive method for detection of a foreign body in an extremity is an ultrasound.

In general, foreign bodies should be seen as hyperechoic reflectors. Depending on the composition of the foreign body, this reflector may or may not have posterior acoustic shadowing. Identification of the foreign body and marking its location on the overlying skin can be invaluable to the surgeon in terms of limiting the exposure required for its removal.4 Given the high spatial resolution of ultrasonography, as well as the fact that the majority of foreign bodies are not radiopaque (i.e., wood), ultrasound is the modality of choice the majority of time for imaging small superficial foreign bodies as opposed to fluoroscopy, conventional radiographs, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

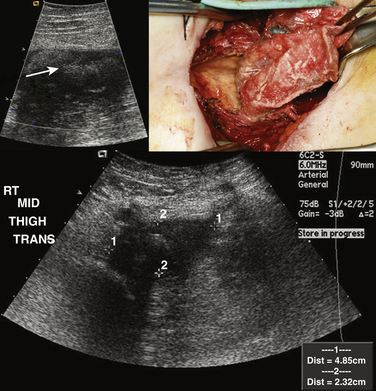

In contrast, an abscess, either with or without associated cellulitis, has a different ultrasonographic appearance. Unlike cellulitis, an abscess is typically well formed, and as a result a discrete measurement of the size and extent can be made. Usually complex in appearance, the typical abscess has a thick wall, which may have increased Doppler flow. Internally, there may be some low level echoes representing complex fluid within the abscess. Again, careful examination is necessary to exclude a foreign body because the presence of a foreign body most often necessitates surgical drainage and removal as opposed to percutaneous drainage alone (Fig. 4.2).2,5–7

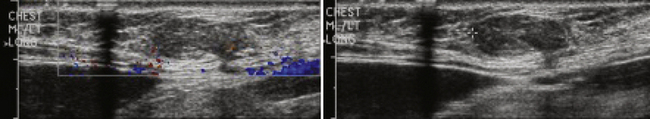

Ganglion Cysts

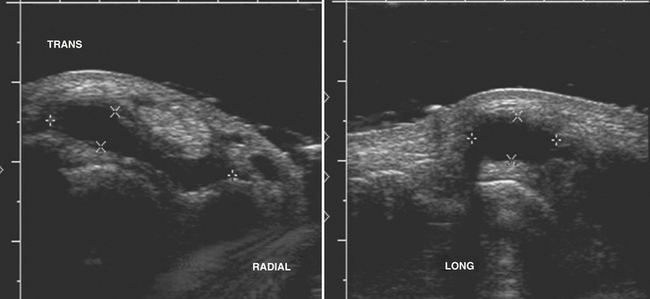

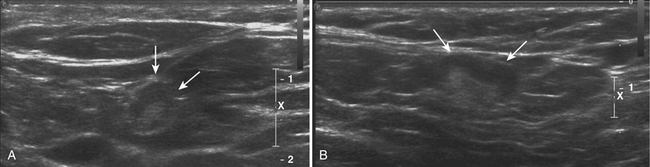

Typically located around the hand and wrist, ganglion cysts are common causes of palpable abnormalities as well as possible generators for extremity pain. The majority arise on the dorsal surface of the hand, with proximity to the scapholunate joint seen in approximately 70% of cases.8 They can also be intimately associated with the flexor tendons of the hand, most commonly around the flexor carpi radialis tendon. Ultrasonographically, these should appear as true cysts, although faint low-level echoes are allowed, given that ganglion cysts may be filled with complex proteinaceous material. Especially in cases in which faint low-level echoes are present, Doppler evaluation is crucial to exclude confusion with a profoundly hypoechoic mass, which is worrisome for a solid soft-tissue mass (Fig. 4.3).9–12

Treatment of these cysts is variable, from observation, to manual rupture, ultrasound-guided steroid injection, and surgery. Unfortunately, given their complex nature, recurrence rates can be quite high and as a result a prior history of treatment of a ganglion cyst should not exclude the diagnosis.13–15

Popliteal (or Baker’s) Cysts

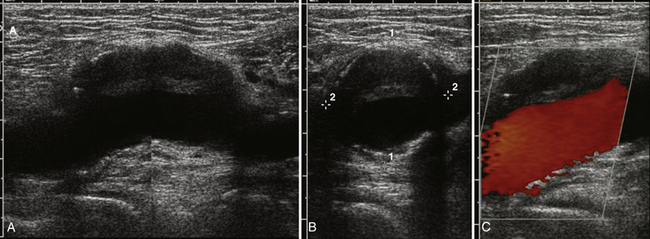

A popliteal, or Baker’s cyst, arises on the posteromedial aspect of the knee within the popliteal fossa. Often a marker for degenerative changes in the knee joint, the popliteal cyst arises between the semimembranosus and medial head of the gastrocnemius.16,17 Patients can present with a palpable mass, swelling, and knee effusion, or they may be asymptomatic.18,19 In addition, given that they have a valve-like mechanism because the cyst neck is trapped between the two muscles, popliteal cysts can wax and wane both in terms of size and degree of symptoms.

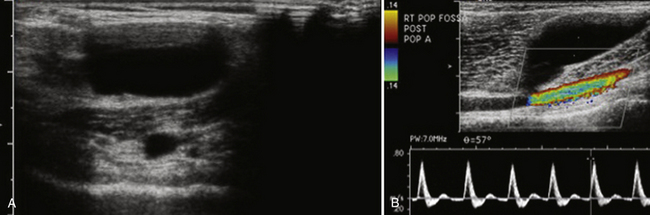

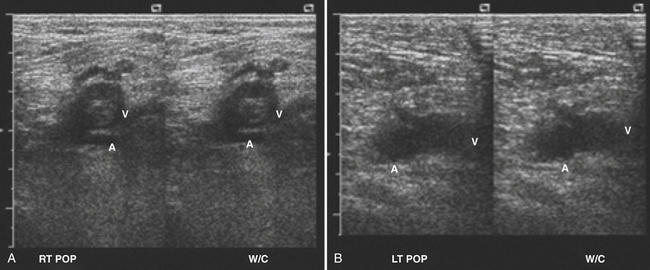

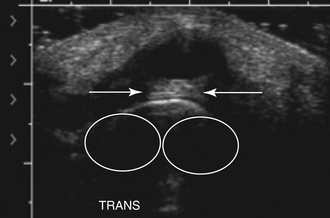

On ultrasound, popliteal cysts are typically purely cystic. The larger they get, the more likely they are to be complex and can even be multiloculated. Internal echoes can be seen, especially in the setting of hemorrhage into the cyst or joint space. Often the neck of the cyst can be identified tapering to dive between the medial head of the gastrocnemius and semimembranosus. Perhaps the most important thing to exclude when imaging a potential popliteal cyst is a popliteal arterial aneurysm. The main way to do this is with color Doppler demonstrating no flow within a popliteal cyst or arterial flow within an aneurysm. This differentiation, obviously, becomes absolutely critical prior to pondering an intervention (Fig. 4.4). In patients with more acute pain with a known popliteal cyst, examination for fluid around and tracking to the cyst can signify recent rupture, which may account for the patient’s symptoms.9,16,19

Treatment includes reassurance and observation, intracystic ultrasound-guided steroid injection, and surgical resection. Unfortunately, as with ganglion cysts in the wrist, recurrence rates regardless of treatment modality are high.19,20

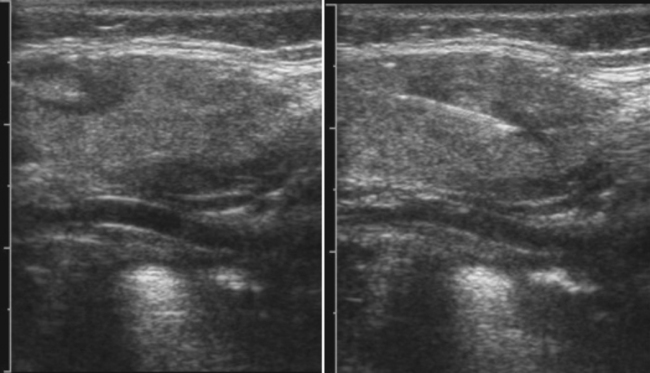

Tenosynovitis

Tenosynovitis is an inflammatory process involving the tendons, either single or multiple, that typically manifests with pain, swelling, and tenderness of the involved tendons.21 Because tenosynovitis can only involve tendons that are encased with synovium, this condition involves primarily the wrists and, to a lesser extent, the ankles. Unfortunately, in some patients the manifesting symptoms can mimic carpal tunnel syndrome and can lead to inappropriate treatment, including surgery.

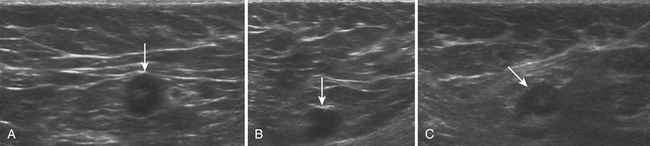

Although tenosynovitis can manifest acutely and be infectious, most often this condition is due to a chronic inflammatory process. Potential etiologies include chronic inflammatory arthritides such as psoriatic and rheumatoid arthritis, overuse injury, and rarely gout. The classic ultrasound picture is that of fluid accumulation with hyperemia within the tendon sheath (Fig. 4.5). The tendon itself is often normal in thickness without hyperemia, which helps distinguish tenosynovitis from tendinosis. MRI is probably more sensitive for the detection of this condition; however, ultrasound can be invaluable in diagnosing tenosynovitis, especially in unsuspected clinical situations such as carpal tunnel syndrome evaluations. Finally, ultrasound is certainly the modality of choice for fluid aspiration for analysis in tenosynovitis.21–23

Joint Effusions

Typically, when evaluating joint effusions, the ultrasonographer examines large joints such as the shoulder, elbow, hip, knee, and ankle.17,24,25 Although the distribution of the effusion varies depending on the shape of the joint and capsule, some rules for the appearance of the effusions can be made. In general, reactive effusions from associated inflammatory, degenerative, or posttraumatic causes should be relatively anechoic with few, if any, internal echoes. The more complex the appearance with internal echoes the effusion becomes, especially in the acute setting, the more one needs to worry about a potentially septic joint. The septic joint is an orthopedic emergency and needs immediate referral with consideration of ultrasound-guided aspiration for diagnosis. When suspicion is high, especially in deeper joints such as the hip, a lower-frequency transducer should be used to penetrate and better visualize the joint capsule.

Solid Soft-Tissue Masses of the Extremities

Normal Lymph Nodes

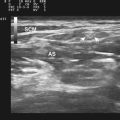

The macroscopic structure of a normal lymph node frequently can be seen with ultrasound. The typical structure includes an outer cortex of lymphoid follicles with a central medulla and a hilum composed of follicles, fat, and vessels. When examining a lymph node with ultrasound and trying to determine whether it is normal, trying to identify these two components can be invaluable. Because the central medulla is largely composed of fat, it should be hyperechoic. In addition, with the use of color Doppler, the hilar feeding vessels can be identified. The peripheral cortex gives definition and shape to the normal lymph node. Typically reniform in shape, a normal lymph node’s greatest dimension is often oriented in a craniocaudal direction with the axial dimension being the shortest dimension. The cortex should be relatively symmetric in thickness as well (Fig. 4.6).26

Pathologic Lymph Nodes

The major hallmark of pathology in a lymph node is architectural distortion. Typically this is most readily appreciated in terms of increased size. An absolute number for abnormal size is difficult to provide. Instead, a ratio of long axis to short axis of greater than 1.5 has been suggested as a potential marker for pathology. Especially in cases of suspected neoplastic disease, normal adjacent lymph nodes may be visible (especially in the neck and axilla) that can provide an internal control for what is normal and what is not. Beside overall increased size, another key feature can be asymmetric growth and enlargement of the cortex. Any nodular appearance, especially if it is more hypoechoic, should be looked upon suspiciously. This feature is typically seen in neoplastic processes rather than inflammatory/reactive nodal disease. In abnormal lymph nodes, architectural distortion can also be seen in the central medulla with obliteration of the normal fatty hilum and a loss of the normal hyperechoic appearance. Normal lymph nodes should also not have cystic areas, which will appear as anechoic areas without internal flow on Doppler, or calcifications, which will appear as areas of acoustic shadowing. Both of these features are again suspicious for malignancy with nodal involvement (Fig. 4.7). In general, when faced with a possibly abnormal lymph node, it is probably best to err on the side of describing it and suggesting further workup, short-interval follow-up, or ultrasound-guided biopsy or fine-needle aspiration.27,28

One special case that may be encountered depending on local demographics is silicone-filled lymph nodes, usually seen within the axilla. Associated with ruptured silicone breast implants or direct silicone injections for breast augmentation, the axillary lymphatics are usually the first line of drainage for the breast tissue. Silicone-infiltrated nodes have a fairly pathognomonic “snowstorm” appearance, which refers to the echogenic mass seen on ultrasound that obscures the normal architecture of the node (Fig. 4.8).29–31 Careful review of the patient’s history can avoid confusion over this situation.

Lipoma

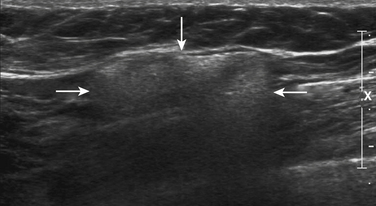

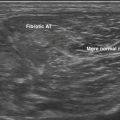

Some of the physical examination features are mirrored on the ultrasonographic examination. Typically soft and compressible on physical examination, with gentle pressure applied with the ultrasound transducer, the subcutaneous lipoma can be seen to deform. This feature is quite unusual for other benign tumors and unheard of in malignant soft-tissue masses. Composed almost entirely of fat, it should be no surprise that most lipomas are isoechoic or slightly hypoechoic relative to the surrounding subcutaneous fat, with relatively little or no internal Doppler flow. Fine, thin septations with a hyperechoic thin-walled capsule may also be seen. Suspicious features include the presence of thick, internal septations, especially with evidence of significant Doppler flow.8,32 Although the diagnosis of a benign lipoma can usually be confidently made with ultrasound, if in doubt, it can be confirmed with limited MRI examination with T1 and fat-saturated T2 images (Fig. 4.9). Typically, unless there are cosmetic reasons, lipomas require no treatment and surgical referral for removal should be uncommon.

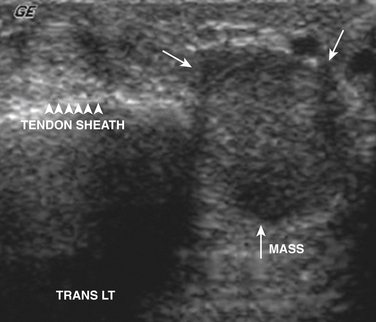

Giant Cell Tumor of the Tendon Sheath

The second most common mass of the hand after ganglion cysts is giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath. These tumors are intimately associated with the tendons of the hand and pathologically are similar to pigmented villonodular synovitis.33 Although benign, these tumors can be locally aggressive and can recur after surgery. Clinically, these tumors manifest with pain as well as a palpable abnormality that has a tendency to be located distally within the fingers.

Unfortunately there is nothing specific on ultrasound to solidify the diagnosis and exclude rarer tumors of the tendon sheath and joints (i.e., synovial sarcoma). Instead these tumors appear as solid masses that rarely have internal calcifications. The main role of ultrasound is to document that the mass is solid and not cystic, thereby ruling out the more common ganglion cyst that can be managed conservatively (Fig. 4.10). Further evaluation with plain films to document internal calcification or matrix, as well as MRI, is indicated in all cases to document extent as well as to confirm diagnosis prior to surgical excision.11,34–38

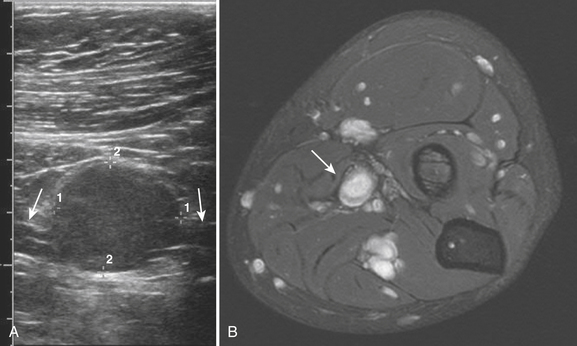

Tumors Involving the Peripheral Nerve

The ultrasound appearance of peripheral nerve sheath tumors has been described since 1986.39 Given the relative frequency of nerve sheath tumors as well as their tendency to cause neurologic symptoms such as dysesthesias and Tinel’s phenomenon, it is not too surprising that with careful examination these tumors frequently are encountered by the peripheral nerve ultrasonographer. In general, these masses can be subdivided into masses due to trauma and benign nerve sheath tumors.

The traumatic neuroma can arise with either partial or complete disruption of the peripheral nerve. Most often there is a compelling history of trauma or surgery with pain localized at or near the neuroma. The neuroma itself has been described as a bulbous concentric enlargement usually at the end of the disrupted nerve or along the course of the nerve if the disruption is only partial. This bulbous appearance at the distal end of the nerve has been described as a “pollywog” appearance of a relatively hypoechoic mass at the nerve terminus. The neuroma along the course of the nerve in cases of partial disruption can be harder to detect and is typically appreciated as a nodularity to the contour of the nerve, best seen in a longitudinal view.

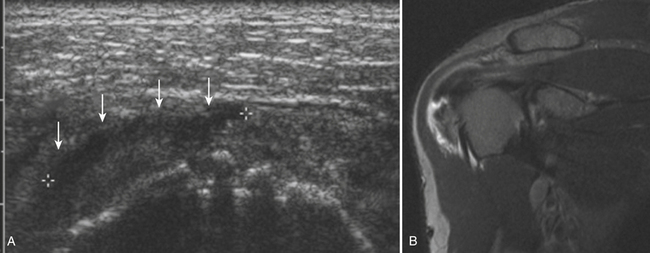

True benign tumors of the peripheral nerve are most often peripheral schwannomas or solitary neurofibromas and can grow quite large prior to detection. Usually hypoechoic on ultrasound, especially the larger tumors can have internal cystic areas. As opposed to the nodularity or “pollywog” appearance of the posttraumatic neuroma, these peripheral nerve sheath tumors are focal, with the normal-appearing nerve entering and exiting the focal mass. This appearance is pathognomonic and can be confirmed with MRI, thereby obviating the need for biopsy to establish a diagnosis (Fig. 4.11).40

Unfortunately, although exceedingly rare, malignant peripheral nerve sheath a tumors can also occur. These malignant tumors, of which the most common is a spindle cell sarcoma, typically manifest differently than benign tumors, with rapid enlargement and progressive neurologic symptoms. Just as their clinical presentation is usually more aggressive, so too is their ultrasonographic appearance. These sarcomas are more likely to be poorly defined, hypoechoic, and heterogeneous; for example, they can also develop prominent areas of cystic of necrosis. In addition, they can also have an internal matrix with cartilage or heterotopic ossification that appears as posterior shadowing on ultrasound. Any suspicious presentation or ultrasound features should be treated with due caution and consideration for referral. Additional imaging with MRI should be strongly considered.40

Salivary Glands

The salivary glands of the head and neck are likely to be rarely imaged by the peripheral ultrasonographer. Although the facial nerve does pierce the parotid glands, in general, their location in the head and neck is far enough removed from the peripheral nerves of the extremity to be of little concern. That being said, especially given the growing practice of ultrasound-guided botulinum toxin for the treatment of refractory sialorrhea, the salivary glands merit a brief discussion.41,42

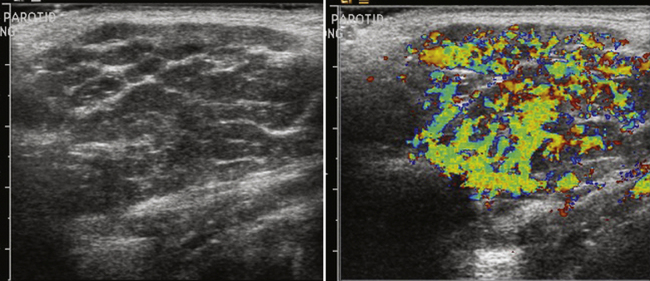

The major salivary glands imaged are the parotid and submandibular glands. There are multiple other minor salivary glands throughout the head and neck, but these are most often too small to characterize and resolve with ultrasound, let alone attempt ultrasound-guided injection. The normal ultrasonographic appearance of the salivary glands is isoechoic and fairly uniform in appearance. Focal areas of architectural distortion with masslike enlargement should be viewed with suspicion. Most masses of the parotid gland are benign, although benign tumors become less common in the smaller salivary glands, including the submandibular glands. Tumors of the salivary glands are typically hypoechoic and uniform in appearance. Larger tumors, especially Warthin’s tumors, can have internal cystic components that may help one favor their diagnosis over other tumors such as the more common pleomorphic adenoma.43–46 Especially for the peripheral nerve ultrasonographer who inadvertently images one of these tumors, no interventions should be made and the patient should be referred for further workup and surgical excision, if indicated (Fig. 4.12).

In addition to masses, autoimmune disorders such as Sjögren’s disease can also be seen in the salivary glands, especially the parotid gland. This autoimmune disease, which can also have associated neurologic symptoms, involves primarily the salivary glands, but the lacrimal glands can also be involved, although they are harder to image with ultrasound. Early in the disease course the gland appears diffusely hypoechoic relative to a normal gland. With progression of the disease, a more heterogeneous appearance with internal cystic areas and increased vascular flow on Doppler with associated glandular enlargement is seen. (Fig. 4.13). In patients with known Sjögren’s disease, ultrasound is mainly used to survey the glands for possible lymphomatous transformation.45,47,48

Metastatic Disease and Soft-Tissue Sarcomas

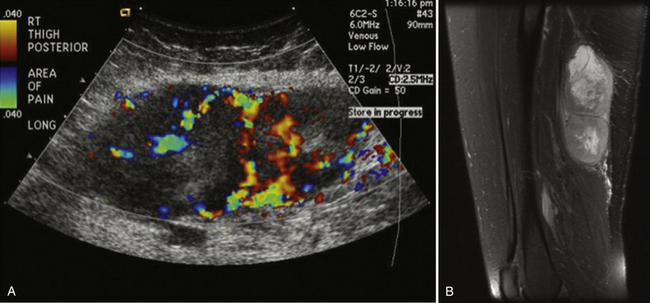

Ultrasound is usually not the modality of choice for evaluation of soft-tissue sarcomas and metastatic disease with subcutaneous nodules. Both of these can initially manifest with pain and possible focal neurologic symptoms due to compression and, as a result, the peripheral nerve ultrasonographer can be the first clinician to encounter these diseases. Whereas usually metastatic disease is seen in lymph nodes, it can also manifest with focal deposits in the subcutaneous tissues and muscles, especially melanoma. Sarcomas are pathologically heterogeneous with a wide variety of derivative cells of origin. A full discussion of sarcomas is obviously beyond the scope of this chapter, but fortunately most sarcomas and metastatic disease deposits in the soft tissues have a similar appearance, which is relatively characteristic and should prevent the careful ultrasonographer from labeling them as benign.

Metastatic or sarcomatous masses should be markedly hypoechoic and ill-defined. Sarcomas can become quite large and have an infiltrating appearance. Doppler evaluation will reveal internal flow, although if the mass is quite large, internal cystic areas of necrosis may be without Doppler flow. Depending on the cell of origin, internal calcified matrix may be seen, which will appear as a hyperechoic reflector with posterior acoustic shadowing. These masses should not be biopsied except after referral and surgical evaluation because potential for tumor seeding along the biopsy tract is possible and may preclude a limb-salvage operation. Instead, referral with plain-film and MRI evaluation is recommended in all cases in which the peripheral nerve ultrasonographer is suspicious (Fig. 4.14).3,49–51

Disorders of Peripheral Veins and Arteries

Aneurysms

A thorough evaluation with gray scale imaging in longitudinal and transverse dimensions is important to document not only the maximal cross-sectional diameter but also the length of segment involved. Careful measurements must include the entire aneurysm from outer wall to outer wall. In order to measure the maximal measurements correctly, the maximal anteroposterior measurement should be made on the longitudinal view to prevent overestimation of the measurement on the transverse view by imaging at an oblique view. Doppler evaluation can certainly make aneurysms more conspicuous and confirm the fact that it is arterial in nature, but Doppler will often underestimate the transverse dimension as aneurysm walls may have mural thrombus within them that will not have flow (Fig. 4.15).52

Conventional atherosclerotic aneurysms are most often uniform or fusiform in shape. The more eccentric or saccular they appear, especially within any atypical features, should at least raise the question of a pseudoaneurysm or mycotic aneurysm and prompt further evaluation.

Pseudoaneurysm

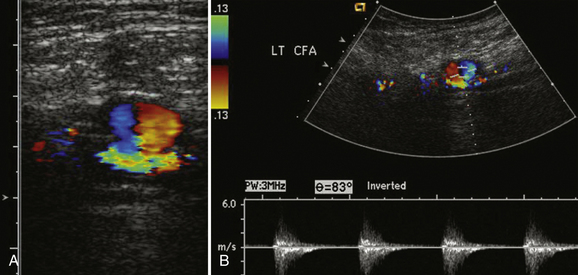

As opposed to true aneurysms, pseudoaneurysms have on occasion been reported to cause nerve compression syndromes, particularly in the upper extremities.53 Usually posttraumatic in origin, pseudoaneurysms differ from true aneurysms in that there is a defect in the two inner layers of the arterial wall with an intact and normal external adventitia layer. Most commonly seen after angiography involving the femoral artery, pseudoaneurysms can also be seen after phlebotomy with accidental arterial injury, direct external trauma, as well as an adjacent infectious or inflammatory process, which can damage the arterial wall.54,55 This defect causes an asymmetric bulging of the lumen through these defective layers with the appearance of a saccular outpouching. Beside the potential for peripheral nerve compression, pseudoaneurysms are also important to recognize because they can rupture, become infected, and serve as an embolic source for peripheral emboli.

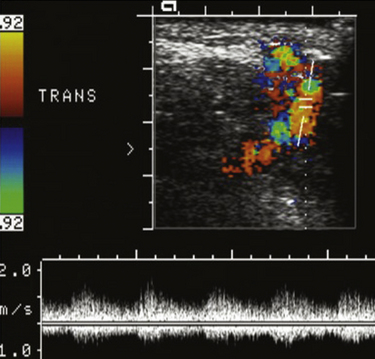

One of the more classic ultrasound findings is that of a pseudoaneurysm. Typically, direct communication with the artery can be demonstrated via a slender neck. Within the pseudoaneurysm itself, color Doppler demonstrates a classic “yin-yang” appearance (Fig. 4.16). This appearance is the Doppler representation of the “to-and-fro” flow into the pseudoaneurysm sac and then back out in the parent artery. Documentation of the pseudoaneurysm size is important, as is measurement of the width of the neck. Both of the measurements are important for determination of appropriate management because these can be treated by direct compression to obliteration, percutaneous ultrasound-guided thrombin injection, and surgery. Typically, pseudoaneurysms with wide necks or those associated with arteriovenous fistula cannot be treated percutaneously with thrombin because of the increased risk of distal emboli and the need for a vascular surgeon’s referral for surgical treatment.54–56

Arteriovenous Fistula

A close relative of the posttraumatic pseudoaneurysm is the postcatheterization arteriovenous fistula. An arteriovenous fistula occurs when a direct connection is inadvertently made between a vein and the adjacent artery. Typically, this occurs after attempted venous or arterial catheterization, which inadvertently breeches the companion vessel.54,57 Although most of the time this connection spontaneously heals, in some cases a persistent channel remains and develops an arteriovenous fistula. Although most of these are asymptomatic unless they become quite large, they can overload and result in limb ischemia, limb edema, and potentially cardiac failure.

On ultrasound these are most often encountered in the inguinal region involving the common femoral artery and vein. In the upper extremity they can also be found in the antecubital fossa, which can be a source for arm pain that can be incorrectly diagnosed as a postphlebotomy median neuropathy at the elbow by a referring clinician. Unlike pseudoaneurysms, no discrete mass can be seen on gray scale imaging. As a result, demonstrating an arterial waveform within the vein makes the diagnosis. In addition, the arterial waveform can be low resistance showing excessive diastolic flow. Finally, because the arteriovenous fistula has a turbulent pattern of flow, Doppler imaging demonstrates a speckled pattern of tissue vibration around the fistula (Fig. 4.17). Ultimately, the majority of these in the peripheral vasculature need to be surgically repaired to prevent further symptoms and risk to the extremity. An increasing number of arteriovenous malformations are also being treated via an endovascular arterial route with covered stents that effectively seal the communication.58

Venous Thrombosis

Upper or lower extremity venous thrombosis remains a common cause of extremity pain and edema. From a treatment point of vein, it is important to be able to differentiate between thrombus involving the deep venous system versus the superficial system, as well as to judge the extent of limb involvement. From a practical point of view though, patients with known or suspected venous thrombosis will not be referred to the dedicated peripheral nerve ultrasonographer and, as a result, one needs only to recognize the unsuspected thrombosis that may be completely incidental to the patient’s chief complaint or mimicking neurologic symptoms.

Larger in diameter than their accompanying arteries, peripheral veins typically have thinner walls with low-flow appearance on Doppler, which may be continuous or demonstrate respiratory phasicity, especially the more proximal they are in the extremity. A hallmark of all normal peripheral veins is that they are compressible with relatively gentle pressure from the transducer. Although a thrombus can have a variable appearance, ranging from hypoechoic to anechoic and can be occlusive or nonocclusive, the sine qua non of venous thrombosis is noncompressibility of the vein (Fig. 4.18). If this noncompressibility is seen, assessment with color Doppler should be performed to document whether the thrombosis is occlusive and an attempt to localize the extent of limb involvement is suggested prior to referring the patient for urgent dedicated vascular ultrasound. Another subtle sign of venous obstruction is the loss of the normal respiratory phasicity seen in proximal large veins. This can be an especially important clue in large, proximal veins that cannot be compressed due to overlying structures such as the subclavian vein with the overlying clavicle.

In terms of dating the age of the thrombosis, the size of the thrombosed vein, presence of collateral veins, and the echogenicity of the clot can help the clinician. In general, with acute thrombosis the vein is distended with anechoic clot and no collateral veins. As the clot matures, the thrombus contracts and the vein becomes less distended and more echogenic.59–63 In addition, collateral veins have time to develop and can be seen on Doppler evaluation. Although these rules are not absolute, they do provide a guideline for discussing the thrombus that may be incidentally noted.

Miscellaneous Findings and Artifacts That May Simulate Disease

Inherent to all imaging modalities are artifacts. Understanding these artifacts is key to optimizing image resolution and diagnostic accuracy. Ultrasound is relatively unique in that the artifacts encountered are relatively predictable and often related to the intrinsic properties of the tissue imaged. As a result, although these artifacts cannot always be eliminated, they can, when properly recognized, provide useful information about the tissue type and actually increase diagnostic accuracy. The issue of artifact is also discussed in Chapter 1.

Anisotropy

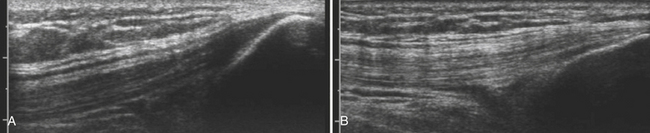

Anisotropy is the intrinsic property of tendons, and to a lesser extent peripheral nerves, in which the amount of sound reflected back to the transducer varies with the angle of insonation (i.e., the angle at which the transducer is held relative to the tendon). This property of tendons results in loss of signal in discrete areas along a tendon, especially as it curves through the field of view, much the way that polarizing glass blocks varying amounts of light, because the angle with which one looks through glass is varied. As a result of anisotropy, tendons require careful examination in multiple planes and with multiple angles to not erroneously diagnose a tendon tear (Fig. 4.19).64,65 In-depth discussion of the diagnosis of tendon tears and evaluation of commonly effected joints such as the shoulder and ankle lies outside the scope of this text; however, limited discussion is useful in case tendon pathology is encountered.

Keeping in mind the danger of anisotropy, careful inspection of a tendon should reveal a fluid-filled gap that persists at all angles in order for a tendon tear to be diagnosed. In general, most large tendons typically tear transversely, whereas smaller tendons can tear either longitudinally or transversely. Careful examination in both planes is critical to the detection of these smaller tendon tears. If possible, careful examination to determine if the tear is complete or partial, and the length of separation between the two tendon ends, is useful to include within the report prior to referral for further clinical evaluation or dedicated musculoskeletal ultrasound or MRI (Fig. 4.20).

Reverberation Artifact

Reverberation artifact can obscure the object of interest in the field of view. This artifact is most commonly seen when two parallel surfaces are positioned orthogonally to the scan plane, especially if one of the surfaces is a strong acoustic reflector. The other surface, which is more superficial, allows only partial transmission of the reflected sound wave while reflecting some of the returning sound wave back into the deeper tissue. This can set up multiple shadows that can mimic false images deep to the initial reflector (Fig. 4.21).66,67 These echoes should be equally spaced. Typically, the artifact can be eliminated by adjusting the angle at which the transducer is held or by adjusting the transducer frequency. Finally, because the most superficial of the reflectors is often the skin, application of more coupling gel can often eliminate this artifact altogether.

Posterior Acoustic Shadowing

Posterior acoustic shadowing occurs when the transmitted sound wave is either entirely reflected back to the transducer or severely attenuated and absorbed due to the nontransmissible property of the tissue. This is most commonly seen with calcifications, which do not permit transmission of the acoustic wave. The result is that deep to the calcification interface with the tissue, no echoes are returned, with the result being an anechoic area deep to the calcification. Depending on the size of the calcification, this may be a small area such as coarse calcification in a mass, or much larger such as when imaging bone (Fig. 4.22). Other causes of posterior acoustic shadowing include foreign bodies, gas, or air.67

Conclusion

Ultrasound is capable of discovering a large variety of pathologies in the extremities. A thorough study of the peripheral nervous system cannot be lightly undertaken without a commitment to also recognize these other disease entities that cannot help but be encountered during a career of study. In general, when an unexplained finding is encountered, the safest approach is a thorough attempt to document the abnormality as well as a comprehensive report describing the abnormality prior to referral for further characterization.

1. Hartman D.S., Choyke P.L., Hartman M.S. From the RSNA refresher courses: a practical approach to the cystic renal mass. Radiographics. 2004;24(Suppl 1):S101-115.

2. Boyse T.D., Fessell D.P., Jacobson J.A., et al. US of soft-tissue foreign bodies and associated complications with surgical correlation. Radiographics. 2001;21:1251-1256.

3. Halaas G.W. Management of foreign bodies in the skin. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:683-688.

4. Ballard R.B., Rozycki G.S., Knudson M.M., Pennington S.D. The surgeon’s use of ultrasound in the acute setting. Surg Clin North Am. 1998;78:337-364.

5. Chau C.L., Griffith J.F. Musculoskeletal infections: ultrasound appearances. Clin Radiol. 2005;60:149-159.

6. Blankenship R.B., Baker T. Imaging modalities in wounds and superficial skin infections. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2007;25:223-234.

7. Wilson D.J. Soft tissue and joint infection. Eur Radiol. 2004;14(Suppl 3):E64-E71.

8. Kuwano Y., Ishizaki K., Watanabe R., Nanko H. Efficacy of diagnostic ultrasonography of lipomas, epidermal cysts, and ganglions. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:761-764.

9. Steiner E., Steinbach L.S., Schnarkowski P., et al. Ganglia and cysts around joints. Radiol Clin North Am. 1996;34:395-425. xi-xii

10. Teefey S.A., Dahiya N., Middleton W.D., et al. Ganglia of the hand and wrist: a sonographic analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:716-720.

11. Nguyen V., Choi J., Davis K.W. Imaging of wrist masses. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2004;33:147-160.

12. Bajaj S., Pattamapaspong N., Middleton W., Teefey S. Ultrasound of the hand and wrist. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34:759-760.

13. Bathia N., Malanga G. Ultrasound-guided aspiration and corticosteroid injection in the management of a paralabral ganglion cyst. PM R. 2009;1:1041-1044.

14. Lohela P. Ultrasound-guided drainages and sclerotherapy. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:288-295.

15. Saboeiro G.R., Sofka C.M. Ultrasound-guided ganglion cyst aspiration. HSS J. 2008;4:161-163.

16. Torreggiani W.C., Al-Ismail K., Munk P.L., et al. The imaging spectrum of Baker’s (popliteal) cysts. Clin Radiol. 2002;57:681-691.

17. Friedman L., Finlay K., Jurriaans E. Ultrasound of the knee. Skeletal Radiol. 2001;30:361-377.

18. Shiver S.A., Blaivas M. Acute lower extremity pain in an adult patient secondary to bilateral popliteal cysts. J Emerg Med. 2008;34:315-318.

19. Handy J.R. Popliteal cysts in adults: a review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2001;31:108-118.

20. Chen J.C., Lu C.C., Lu Y.M., et al. A modified surgical method for treating Baker’s cyst in children. Knee. 2008;15:9-14.

21. Backhaus M. Ultrasound and structural changes in inflammatory arthritis: synovitis and tenosynovitis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1154:139-151.

22. McQueen F.M. The MRI view of synovitis and tenosynovitis in inflammatory arthritis: implications for diagnosis and management. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1154:21-34.

23. Rawool N.M., Nazarian L.N. Ultrasound of the ankle and foot. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2000;21:275-284.

24. Valley V.T., Stahmer S.A. Targeted musculoarticular sonography in the detection of joint effusions. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:361-367.

25. Tran N., Chow K. Ultrasonography of the elbow. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2007;11:105-116.

26. Restrepo R., Oneto J., Lopez K., Kukreja K. Head and neck lymph nodes in children: the spectrum from normal to abnormal. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39:836-846.

27. Kunte C., Schuh T., Eberle J.Y., et al. The use of high-resolution ultrasonography for preoperative detection of metastases in sentinel lymph nodes of patients with cutaneous melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1757-1765.

28. Kim E.Y., Ko E.Y., Han B.K., et al. Sonography of axillary masses: what should be considered other than the lymph nodes? J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28:923-939.

29. Adams S.T., Cox J., Rao G.S. Axillary silicone lymphadenopathy presenting with a lump and altered sensation in the breast: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2009;3:6442.

30. Kulber D.A., Mackenzie D., Steiner J.H., et al. Monitoring the axilla in patients with silicone gel implants. Ann Plast Surg. 1995;35:580-584.

31. Roux S.P., Bertucci G.M., Ibarra J.A., et al. Unilateral axillary adenopathy secondary to a silicone wrist implant: report of a case detected at screening mammography. Radiology. 1996;198:345-346.

32. Sakai K., Tsutsui T., Aoi M., et al. Ulnar neuropathy caused by a lipoma in Guyon’s canal: case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2000;40:335-338.

33. Wang Y., Tang J., Luo Y. The value of sonography in diagnosing giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1333-1340.

34. Chiou H.J., Chou Y.H., Chiu S.Y., et al. Differentiation of benign and malignant superficial soft-tissue masses using grayscale and color Doppler ultrasonography. J Chin Med Assoc. 2009;72:307-315.

35. Villani C., Tucci G., Di Mille M., et al. Extra-articular localized nodular synovitis (giant cell tumor of tendon sheath origin) attached to the subtalar joint. Foot Ankle Int. 1996;17:413-416.

36. An S.B., Choi J.A., Chung J.H., et al. Giant cell tumor of soft tissue: a case with atypical US and MRI findings. Korean J Radiol. 2008;9:462-465.

37. Cheng J.W., Tang S.F., Yu T.Y., et al. Sonographic features of soft tissue tumors in the hand and forearm. Chang Gung Med J. 2007;30:547-554.

38. Horcajadas AB, Lafuente JL, de la Cruz Burgos R, et al. Ultrasound and MR findings in tumor and tumor-like lesions of the fingers, Eur Radiol 13:672-685

39. Hughes D.G., Wilson D.J. Ultrasound appearances of peripheral nerve tumours. Br J Radiol. 1986;59:1041-1043. 2003

40. Gruber H., Glodny B., Bendix N., et al. High-resolution ultrasound of peripheral neurogenic tumors. Eur Radiol. 2007;17:2880-2888.

41. Pena A.H., Cahill A.M., Gonzalez L., et al. Botulinum toxin A injection of salivary glands in children with drooling and chronic aspiration. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20:368-373.

42. Capaccio P., Torretta S., Osio M., et al. Botulinum toxin therapy: a tempting tool in the management of salivary secretory disorders. Am J Otolaryngol. 2008;29:333-338.

43. Isa A.Y., Hilmi O.J. An evidence based approach to the management of salivary masses. Clin Otolaryngol. 2009;34:470-473.

44. Yuan W.H., Hsu H.C., Chou Y.H., et al. Gray-scale and color Doppler ultrasonographic features of pleomorphic adenoma and Warthin’s tumor in major salivary glands. Clin Imaging. 2009;33:348-353.

45. Bialek E.J., Jakubowski W., Zajkowski P., et al. US of the major salivary glands: anatomy and spatial relationships, pathologic conditions, and pitfalls. Radiographics. 2006;26:745-763.

46. Taylor T.R., Cozens N.J., Robinson I. Warthin’s tumour: a retrospective case series. Br J Radiol. 2009;82:916-919.

47. Seceleanu A., Pop S., Preda D., et al. Imaging aspects of the lacrimal gland in Sjögren syndrome: case report. Oftalmologia. 2008;52:35-39.

48. Shimizu M., Okamura K., Yoshiura K., et al. Sonographic diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome: evaluation of parotid gland vascularity as a diagnostic tool. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:587-594.

49. Knapp E.L., Kransdorf M.J., Letson G.D. Diagnostic imaging update: soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer Control. 2005;12:22-26.

50. Shelly M.J., MacMahon P.J., Eustace S. Radiology of soft tissue tumors including melanoma. Cancer Treat Res. 2008;143:423-452.

51. Anders J.O., Aurich M., Lang T., Wagner A. Solitary fibrous tumor in the thigh: review of the literature. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2006;132:69-75.

52. Robinson W.P.3rd, Belkin M. Acute limb ischemia due to popliteal artery aneurysm: a continuing surgical challenge. Semin Vasc Surg. 2009;22:17-24.

53. Cartwright M.S., Donofrio P.D., Ybema K.D., Walker F.O. Detection of a brachial artery pseudoaneurysm using ultrasonography and EMG. Neurology. 2005;65:649.

54. Davison B.D., Polak J.F. Arterial injuries: a sonographic approach. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42:383-396.

55. Kapoor B.S., Haddad H.L., Saddekni S., Lockhart M.E. Diagnosis and management of pseudoaneurysms: an update. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2009;38:170-188.

56. Ward E., Buckley O., Collins A., et al. The use of thrombin in the radiology department. Eur Radiol. 2009;19:670-678.

57. Tran H.S., Burrows B.J., Zang W.A., Han D.C. Brachial arteriovenous fistula as a complication of placement of a peripherally inserted central venous catheter: a case report and review of the literature. Am Surg. 2006;72:833-836.

58. Spirito R., Trabattoni P., Pompilio G., et al. Endovascular treatment of a post-traumatic tibial pseudoaneurysm and arteriovenous fistula: a case report and review of the literature. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:1076-1079.

59. Hart J.L., Lloyd C., Niewiarowski S., Harvey C.J. Duplex ultrasound for diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2007;68:M206-209.

60. Orbell J.H., Smith A., Burnand K.G., Waltham M. Imaging of deep vein thrombosis. Br J Surg. 2008;95:137-146.

61. Madhusudhana S., Moore A., Moormeier J.A. Current issues in the diagnosis and management of deep vein thrombosis. Mo Med. 2009;106:43-48.

62. Shakoor H., Santacruz J.F., Dweik R.A. Venous thrombo-embolic disease. Compr Ther. 2009;35:24-36.

63. Schellong S.M. Venous ultrasonography in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients: an updated review. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2008;14:374-380.

64. Rutten M.J., Jager G.J., Blickman J.G. From the RSNA refresher courses: US of the rotator cuff: pitfalls, limitations, and artifacts. Radiographics. 2006;26:589-604.

65. Robinson P. Sonography of common tendon injuries. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:607-618.

66. Saranteas T., Karabinis A. Reverberation: source of potential artifacts occurring during ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia. Can J Anaesth. 2009;56:174-175.

67. Feldman M.K., Katyal S., Blackwood M.S. US artifacts. Radiographics. 2009;29:1179-1189.