CHAPTER 7 Bariatric Surgery

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF MORBID OBESITY

Morbid obesity is the leading public health crisis of the industrialized world (see Chapter 6).1,2 The prevalence of obesity in the United States continues to rise at an alarming rate, with two thirds of adults currently considered overweight, half of whom are obese.3 Being overweight is defined by the body mass index (BMI): normal BMI = 25 kg/m2; BMI for obesity > 30 kg/m2; BMI for morbid obesity > 40 kg/m2; and BMI for supermorbid obesity > 50 kg/m2. Rising rates of obesity are seen across the United States in men and women and in all major racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups.4 Morbid obesity reduces life expectancy by five to 20 years and, for the first time in history, it is predicted that the current generation may have a shorter life expectancy than the last.5,6

BARIATRIC SURGERY AS TREATMENT FOR MORBID OBESITY

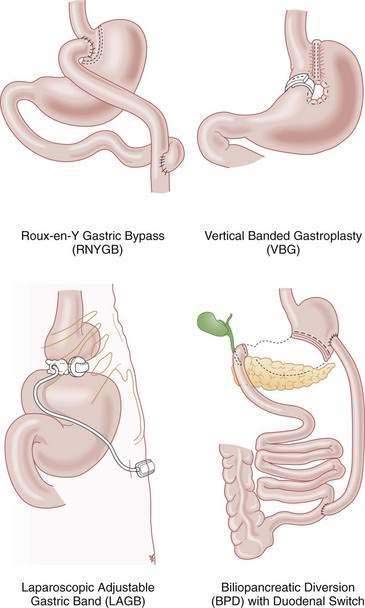

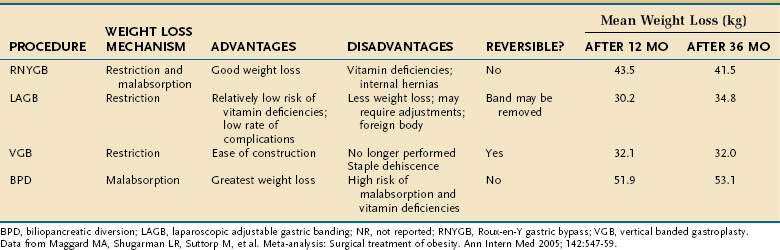

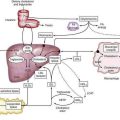

Bariatric surgery remains the only effective and enduring treatment for morbid obesity. Since 1997, the number of bariatric surgical procedures in the United States has grown sevenfold as evidence has proven their safety and efficacy.7 Weight loss operations can be classified as malabsorptive or restrictive (Fig. 7-1). Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RNYGB), which accounts for 88% of bariatric procedures in the United States, is restrictive and malabsorptive. Biliopancreatic diversion–duodenal switch (BPD-DS), the other malabsorptive procedure, is not as commonly performed in the United States because of its higher risk profile. Purely restrictive procedures include the laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB), vertical banded gastroplasty (VBG), gastrectomy, and sleeve gastrectomy procedures, all of which reduce the size of the stomach so it is unable to accommodate more than a few ounces of food. VBG is no longer performed commonly because of its potential for staple line dehiscence and subsequent weight gain. Advantages, disadvantages and complications of the major weight loss operations are shown in Tables 7-1 and 7-2.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

To qualify for bariatric surgery, patients must meet the 1991 NIH consensus criteria, which include having a BMI > 40 kg/m2 or a BMI > 35 kg/m2 with obesity-related comorbidities, and at least six months of documented, medically supervised weight loss attempts.8 Some bariatric surgeons require patients to lose additional weight through diet and exercise between the time of initial bariatric surgery consultation and the date of operation. This additional required preoperative weight loss is not correlated with comorbidity resolution or complication rates, but is associated with shorter operative times and greater weight loss at one year after the surgery; therefore, it should be encouraged in all patients.9,10

Prior to surgery, patients must complete an extensive screening process, including consultation with a surgeon, psychologic evaluation, nutrition consultation, chest roentgenography, electrocardiography, pulmonary function testing, a sleep study, and an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). The EGD was recommended by the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery to detect and treat any upper gastrointestinal lesions that may cause postoperative complications or influence the decision of which type of bariatric surgery should be performed.11

In a study of 272 gastric bypass patients who underwent preoperative EGD, 12% had clinically significant preoperative findings that included erosive esophagitis (3.7%), Barrett’s esophagus (3.7%), gastric ulcer (2.9%), erosive gastritis (1.8%), duodenal ulcer (0.7%), and gastric carcinoid (0.3%); 1.1% had more than one lesion. Given that 12% of patients who eventually underwent RNYGB had clinically significant preoperative findings, and only 67% of them had upper gastrointestinal symptoms, it is important to perform EGD preoperatively, because the excluded distal stomach cannot be evaluated easily after a RNYGB procedure.12 Patients undergoing LAGB surgery also should undergo a preoperative EGD, especially to evaluate gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Gastric banding leads to satiety and weight loss by creating a small restrictive stomach with a slow gastric emptying time. Patients who overfill their small stomach pouch post-LAGB can force food and stomach acid back up into their lower esophagus, thereby worsening any preexisting GERD.13,14 In addition, overzealous banding adjustment may lead to pseudoachalasia with an increased pressure zone below the lower esophageal sphincter, furthering any incompetence.

EFFICACY

The steep rise in the use of bariatric surgery can be attributed to its proven efficacy as a treatment for morbid obesity. Two meta-analyses have provided strong validation that bariatric surgery leads to successful weight loss and mortality reduction.15,16 A meta-analysis by Buchwald and colleagues that included 22,094 patients found the mean percentage of excess weight loss (EWL) for all patients to be 61.2%.15 EWL is highest for VBG (68.2%), lower for RNYGB (61.6%), and lowest for LAGB (47.5%). A meta-analysis by Maggard and associates found similar weight loss trends at three or more years postoperatively, with the greatest weight loss achieved after the malabsorptive procedures of BPD-DS (53 kg) and RNYGB (42 kg), and less weight loss after the restrictive LAGB (35 kg) and gastroplasty (32 kg).16

EFFECTS ON MORTALITY AND MORBIDITY

Such substantial weight loss is associated with a clear reduction in long-term mortality. A retrospective cohort study of 9,949 RNYGB patients matched to 9,628 severely obese controls found that having RNYGB surgery reduces the adjusted long-term mortality from any cause of death by 40%.17 Among RNYGB patients, mortality was decreased 56% from coronary artery disease, 92% from diabetes, and 60% from cancer. In another study, a 14% decrease in cancer incidence was shown in patients who underwent RNYGB, the biggest reductions in which were seen among types of cancers that are considered obesity-related: esophageal adenocarcinoma (2% reduction), colorectal cancer (30% reduction), breast cancer (9%), uterine cancer (78%), non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (46%), and multiple myeloma (54%).18 The lower cancer risk of patients after RNYGB presumably was caused by weight loss, which has been shown in many studies to reduce cancer incidence. Furthermore, once obese patients lose weight, they may have better access to needed health surveillance, such as Pap smears and colonoscopy. Finally, given that increased BMI leads to worse surgical oncologic outcomes, it may be surmised that with weight loss, a better surgical outcome may be anticipated.

Overall, bariatric surgery dramatically improves survival and decreases mortality from all disease-related causes of death. Only rate of deaths not caused by disease, including deaths resulting from accidents and suicide, increased after bariatric surgery and were 58% higher in the RNYGB patients17; it has been speculated that alcohol abuse may explain why accidents and suicides were higher in the surgical group. One study demonstrated altered alcohol metabolism after gastric bypass surgery, with the gastric bypass patients having a greater peak alcohol level and a longer time for the alcohol level to reach a zero blood level than in controls.30 Another study of bariatric surgery candidates found that 9% reported having attempted suicide and 19% reported having abused alcohol preoperatively.19 There is concern that this vulnerable patient population has additional difficulty with the psychological adjustments to weight loss, further supporting the need for psychological counseling before and after surgery.20,21

In addition to benefiting from a decreased mortality, bariatric patients benefit from decreased morbidity. Morbidly obese patients suffer from more intense gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., abdominal pain, heartburn) and sleep disturbances than normal-weight patients. By six months after RNYGB, however, the frequency and severity of gastrointestinal symptoms of many morbidly obese patients have decreased to levels seen in normal weight patients. Dysphagia is common in morbidly obese patients, all of whom experience increased intra-abdominal pressure. Dysphagia is the only gastrointestinal symptom that worsens after RNYGB, probably from further increase in esophageal pressure because of overeating and overfilling of the restrictive small gastric pouch; this observation again underscores the need for preoperative and postoperative education regarding diet.27

Quality of life, as measured by the validated SF36 survey, improves greatly after RNYGB surgery. Preoperatively, morbidly obese patients score significantly lower than U.S. population norms in the categories of general health, vitality, physical functioning, bodily pain, emotional, and social functioning. As soon as three months following RYNGB, these same patients scored no differently than U.S. norms in these categories.28

COMORBIDITY RESOLUTION

Weight loss surgery is a singular medical intervention that can reverse or improve the numerous medical conditions associated with obesity. RNYGB results in a substantial reduction in cardiac risk factors with the following resolution rates: diabetes (82%), hypertension (70%), and hyperlipidemia (63%).29 Gastric bypass has assembled the most evidence of comorbidity resolution; however, all weight loss operations result in some degree of improvement. The meta-analysis by Buchwald and coworkers15 found that bariatric surgery reverses, ameliorates, or eliminates major cardiovascular risk factors:

One study found resolution of all conventional abnormal risk factors, including serum levels of total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), triglyceride, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, homocysteine, and lipoprotein A at one year after RNYGB.30

The Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) Study has provided further demonstration of the ameliorative effect of bariatric surgery. At 10 years of follow-up, surgically treated obese patients had 25% reduction in hypertension, 43% improvement in HDL, and 75% reduction in diabetes compared with the medically treated group.31

Beyond the significant improvement in cardiac risk factors, weight loss surgery also provides substantial relief of the many medical problems that obesity causes. One study found that a leading digestive health complaint, GERD, is cured or improved at a 96% rate.29 Other studies also have documented a highly significant reduction in GERD symptoms after bariatric surgery.27,32 One study of patients with severe GERD prior to RNYGB found significant declines in use of proton pump inhibitors (44% to 9%) and H2 blockers (60% to 10%) at postoperative times ranging from six to 36 months.33 GERD resolution rates following RNYGB are so robust that RNYGB is a suggested treatment for recalcitrant GERD in morbidly obese patients, especially given the lack of efficacy of antireflux surgery in the obese.34,35

Prior to surgery, morbidly obese patients report significantly more symptoms of abdominal distress, including pain, gnawing sensations, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal distention than normal controls. After RNYGB, these symptoms are reduced to levels comparable with those of normal controls.27,32 Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a constellation of symptoms (see Chapter 118), including abdominal pain or discomfort, altered bowel habits (diarrhea, constipation), increased flatus, and bloating or distention. Preoperative morbidly obese patients rate their severity of IBS symptoms significantly higher than controls. Following RNYGB, these same patients rated the severity of their symptoms significantly lower than they did preoperatively and at levels equivalent to those of control IBS patients.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) comprises a histologic spectrum of fatty liver ranging from simple steatosis to portal fibrosis, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and cirrhosis.36 The most advanced forms of NAFLD are strongly associated with the metabolic syndrome—that is, obesity and hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and diabetes mellitus—and NAFLD is the most prevalent liver disease in the United States.37,38 In a postmortem series of obese non-drinkers, hepatic steatosis was present in 76% and NASH was present in 18.5%.39 Mounting evidence suggests that current bariatric surgical procedures actually may be beneficial for NAFLD.40 One study documented that histologic improvements as measured by steatosis (89.7% improvement), hepatocellular ballooning (58.9% improvement), and centrilobular-perisinusoidal fibrosis (50% improvement) occur within a mean period of 18 months after RNYGB. The diagnosis of NASH was made in 58.9% of patients preoperatively and none of them were found to have NASH in postoperative liver biopsies.41

Weight loss surgery has been shown to improve sleep apnea with the following rates: banding (95%), gastroplasty (77%), gastric bypass (87%), and BPD-DS (95%).15 Another study has demonstrated that after RNYGB, patients have significantly fewer sleep disturbances with regard to falling asleep, insomnia, and feeling rested on awakening.27

Morbidly obese patients undergoing RNYGB have demonstrated an 88% resolution or improvement of joint disease.29 Furthermore, weight loss surgery has been demonstrated to eliminate or improve obesity-associated venous stasis disease, gout, asthma, pseudotumor cerebri, urinary incontinence, and infertility.29

SURGICAL COMPLICATIONS

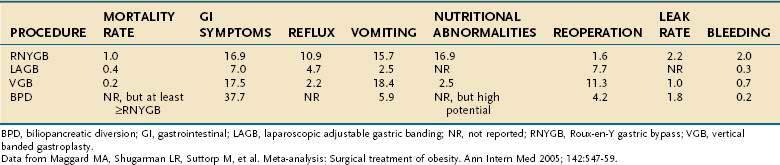

The risk of operative mortality and complications may temper some enthusiasm for bariatric surgery. Based on a meta-analysis by Maggard and colleagues,16 mortality rates were shown to depend on the procedure performed. The average mortality rates for the different procedures are banding (0.4%, 0.01% to 2.1%), gastroplasty (0.2%, 0% to 16.8%), gastric bypass (1%, 0.2% to 2.5%), and BPD-DS (0.9%, 0.01% to 1.3%).

Complications of bariatric procedures include anastomotic leak or stenosis, pulmonary embolus, gastrointestinal bleeding, nutritional deficiencies, wound complications, bowel obstructions, ulcers, hernias, respiratory, cardiac, and implant device-related complications. Among the different surgical procedures, the rate of complications is proportional to the amount of weight loss produced by each operation: banding (7%), gastroplasty (18%), gastric bypass (17%), and BPD-DS (38%).16,42

Marginal ulcers are estimated to occur in 1% to 16% of gastric bypass patients.43,44 Perforated marginal ulcers occur in 1% of RNYGB patients. Ulcer perforation is linked to smoking and use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or glucocorticoids.45 The use of nonabsorbable sutures, as opposed to absorbable sutures, for the inner layer of the gastrojejunal anastomosis is associated with increased ulcer incidence.46 The presence of H. pylori also increases risk for marginal ulcers.47 Postoperatively, it is common practice for bariatric surgeons to begin a six-month ulcer prophylaxis program with proton pump inhibitors. If a marginal ulcer is recalcitrant to medical therapy, the possibility of a gastric-gastric fistula must be entertained. If a gastric-gastric fistula is present with a marginal ulcer, then surgical correction is mandated. Gastrointestinal bleeding occurs postoperatively in 2.0% of RNYGB, 0.7% of VBG, 0.3% of LAGB, and 0.2% of BPD-DS procedures. Another potential complication is an anastomotic gastric pouch or duodenal leak, which occurs after 2.2% of RNYGB, 1.0% of VBG, and 1.8% of BPD-DS procedures.16

Nutritional and vitamin deficiencies and electrolyte abnormalities occur in 16.9% of RNYGB patients and 2.5% of patients having VBG.16 Patients who do not take daily vitamins postoperatively or patients who experience frequent vomiting are at increased risk of developing such deficiencies, most common of which are protein, iron, vitamin B12, folate, calcium, and the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K.48

The parietal cells of the stomach produce intrinsic factor, which is necessary for vitamin B12 absorption in the terminal ileum. Patients who undergo RNYGB may develop vitamin B12 deficiency because RNYGB separates the parietal cells in the fundus and body of the stomach from the smaller gastric pouch, which receives ingested food. There is, therefore, no contact between ingested food and intrinsic factor until the intersection of the Roux limb in the jejunum.49,50 In addition, following RNYGB, the parietal cells of the stomach often cease to produce intrinsic factor, presumably because the fundus no longer has any contact with food.51 It has been shown that restrictive bariatric surgery does not cause vitamin B12 deficiency because the parietal cells remain in contact with the ingested food.52 Fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies are most often seen following BPD-DS operations because food has very little exposure to the biliary and pancreatic secretions necessary for fat digestion, and there is little exposure of food to the ileum, where fat is normally absorbed. Calcium and folate deficiency can occur because they are absorbed in the duodenum and proximal jejunum. These segments of the digestive tract are commonly bypassed in gastric bypass and duodenal switch surgery. The fat-soluble vitamin D is necessary for calcium absorption, and so vitamin D deficiency will further contribute to any calcium deficiency.48 Thiamine deficiency may lead to Wernicke’s encephalopathy, a syndrome of confusion, ataxia, ophthalmoplegia, and impaired short-term memory. If thiamine deficiency is suspected, the patient should be given intravenous or intramuscular thiamine immediately in order to increase the chances of symptom resolution.53

Meta-analysis has revealed that gastroesophageal reflux occurs postoperatively in 10.9% of RNYGB, 2.2% of VBG, and 4.7% of LAGB patients.16 Approximately half of LAGB patients will experience some degree of heartburn and acid regurgitation.54 Pseudoachalasia and esophageal dysmotility are late complications of LAGB and usually reverse on removal of the gastric band.55 Among RNYGB patients, postoperative dysphagia is significantly worse than normal weight controls, but not significantly worse than the patient’s matched preoperative symptoms.27

A high incidence of gallstone formation has been well documented when morbidly obese patients undergo rapid surgically induced weight loss.56 It was shown in a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial that a daily dosage of 600 mg ursodiol for the first six months after surgery reduces the incidence of gallstones to 2%.57 It is therefore recommended that all bariatric patients take ursodiol for six months postoperatively to reduce the risk of this largely preventable complication.

Beyond the type of procedure, there are identified risk factors for complications after bariatric surgery, including older age, male gender, greater BMI, comorbidities, and Medicare insurance status.58–62 The increased risk for Medicare patients is beyond age, given that eligibility for Medicare is disability, which may affect outcomes. Although patients with the most risk factors carry the highest risk for surgery, they also may derive the most benefit from bariatric surgery, given the disease burden they carry.63 Of note, complications may not affect long-term weight loss, which is the outcome that best predicts long-term mortality risk.9

VOLUME EFFECT AND CENTER OF EXCELLENCE MOVEMENT

Many of the reported studies regarding morbidity and mortality had been completed prior to the many improvements in current surgical technique.28 In addition, surgeon and hospital experience can mitigate the risks associated with weight loss surgery. The best demonstrated and most protective effect against complications is an experienced surgeon and hospital.63–66 Clearly, there is benefit in having this complex and demanding surgery performed by experienced and committed surgeons operating in a dedicated health care facility.

None of the previously mentioned perioperative risk factors can be modified, with the exception of the volume status of the surgeon and hospital. For gastric bypass surgery, it has been demonstrated that a high-volume surgeon and high-volume hospital lead to decreased morbidity and mortality.63–66

In the United States, this volume outcome effect has been recognized by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which now require Medicare patients to undergo surgery only at a Bariatric Surgery Center of Excellence.67 Numerous criteria enable a center to become a Bariatric Surgery Center of Excellence, but the primary criteria are a surgeon volume of more than 50 cases and hospital volume exceeding 125 cases annually. Although a referral to a Bariatric Surgery Center of Excellence may lead to decreased morbidity and mortality, this referral pattern must be balanced with appropriate and sufficient access to care for a vulnerable population without other therapeutic options.

Adams TD, Gress RE, Smith SC, et al. Long-term mortality after gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:753-61. (Ref 17.)

Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724-37. (Ref 15.)

Fontaine KR, Redden DT, Wang C, et al. Years of life lost due to obesity. JAMA. 2003;289:187-93. (Ref 5.)

Hagedorn JC, Encarnacion B, Brat GA, Morton JM. Does gastric bypass alter alcohol metabolism? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:543-8. (Ref 30.)

Klein S, Mittendorfer B, Eagon JC, et al. Gastric bypass surgery improves metabolic and hepatic abnormalities associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1564-72. (Ref 40.)

Maggard MA, Shugarman LR, Suttorp M, et al. Meta-analysis: surgical treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:547-59. (Ref 16.)

Nguyen NT, Goldman C, Rosenquist CJ, et al. Laparoscopic versus open gastric bypass: A randomized study of outcomes, quality of life, and costs. Ann Surg. 2001;234:279-89.

Nguyen NT, Paya M, Stevens CM, et al. The relationship between hospital volume and outcome in bariatric surgery at academic medical centers. Ann Surg. 2004;240:586-93. (Ref 64.)

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549-55. (Ref 1.)

Olshansky SJ, Passaro DJ, Hershow RC, et al. A potential decline in life expectancy in the United States in the 21st century. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1138-45. (Ref 6.)

Santry HP, Gillen DL, Lauderdale DS. Trends in bariatric surgical procedures. JAMA. 2005;294:1909-17. (Ref 7.)

Schauer PR, Ikramuddin S, Gourash W, et al. Outcomes after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2000;232:515-29. (Ref 29.)

Sjöström L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2683-93. (Ref 31.)

Sugerman HJ, Brewer WH, Shiffman ML, et al. A multicenter, placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, prospective trial of prophylactic ursodiol for the prevention of gallstone formation following gastric-bypass-induced rapid weight loss. Am J Surg. 1995;169:91-6. (Ref 57.)

Williams DB, Hagedorn JC, Lawson EH, et al. Gastric bypass reduces biochemical cardiac risk factors. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:8-13. (Ref 58.)

1. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549-55.

2. Yoon KH, Lee JH, Kim JW, et al. Epidemic obesity and type 2 diabetes in Asia. Lancet. 2006;368:1681-8.

3. Parikh NI, Pencina MJ, Wang TJ, et al. Increasing trends in incidence of overweight and obesity over 5 decades. Am J Med. 2007;120:242-50.

4. Mokdad AH, Bowman BA, Ford ES, et al. The continuing epidemics of obesity and diabetes in the United States. JAMA. 2001;286:1195-200.

5. Fontaine KR, Redden DT, Wang C, et al. Years of life lost due to obesity. JAMA. 2003;289:187-93.

6. Olshansky SJ, Passaro DJ, Hershow RC, et al. A potential decline in life expectancy in the United States in the 21st century. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1138-45.

7. Santry HP, Gillen DL, Lauderdale DS. Trends in bariatric surgical procedures. JAMA. 2005;294:1909-17.

8. NIH consensus statement covers treatment of obesity. Am Fam Physician. 1991;44:305-6.

9. Alvarado R, Alami RS, Hsu G, et al. The impact of preoperative weight loss in patients undergoing laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2005;15:1282-6.

10. Harnisch MC, Portenier DD, Pryor AD, et al. Preoperative weight gain does not predict failure of weight loss or co-morbidity resolution of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:445-50.

11. Sauerland S, Angrisani L, Belachew M, et al. Obesity surgery: Evidence-based guidelines of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (EAES). Surg Endosc. 2005;19:200-21.

12. Mong C, Van Dam J, Morton J, et al. Preoperative endoscopic screening for laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass has a low yield for anatomic findings. Obes Surg. 2008;18:1067-73.

13. Gutschow CA, Collet P, Prenzel K, et al. Long-term results and gastroesophageal reflux in a series of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:941-8.

14. Milone L, Daud A, Durak E, et al. Esophageal dilation after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1482-6.

15. Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724-37.

16. Maggard MA, Shugarman LR, Suttorp M, et al. Meta-analysis: Surgical treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:547-59.

17. Adams TD, Gress RE, Smith SC, et al. Long-term mortality after gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:753-61.

18. Adams TD, Stroup AM, Gress RE, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality after gastric bypass surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17:796-802.

19. Sansone RA, Wiederman MW, Schumacher DF, Routsong-Weichers L. The prevalence of self-harm behaviors among a sample of gastric surgery candidates. J Psychosom Res. 2008;65:441-4.

20. Hsu LK, Benotti PN, Dwyer J, et al. Nonsurgical factors that influence the outcome of bariatric surgery: A review. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:338-46.

21. Waters GS, Pories WJ, Swanson MS, et al. Long-term studies of mental health after the Greenville gastric bypass operation for morbid obesity. Am J Surg. 1991;161:154-7.

22. Hsu LK, Betancourt S, Sullivan SP. Eating disturbances before and after vertical banded gastroplasty: A pilot study. Int J Eat Disord. 1996;19:23-34.

23. Hsu LK, Sullivan SP, Benotti PN. Eating disturbances and outcome of gastric bypass surgery: A pilot study. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;21:385-90.

24. Dutta S, Morton J, Shepard E, et al. Methamphetamine use following bariatric surgery in an adolescent. Obes Surg. 2006;16:780-2.

25. Ertelt TW, Mitchell JE, Lancaster K, et al. Alcohol abuse and dependence before and after bariatric surgery: A review of the literature and report of a new data set. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:647-50.

26. Guisado Macias JA, Vaz Leal FJ. Psychopathological differences between morbidly obese binge eaters and non-binge eaters after bariatric surgery. Eat Weight Disord. 2003;8:315-18.

27. Clements RH, Gonzalez QH, Foster A, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms are more intense in morbidly obese patients and are improved with laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2003;13:610-14.

28. Nguyen NT, Goldman C, Rosenquist CJ, et al. Laparoscopic versus open gastric bypass: A randomized study of outcomes, quality of life, and costs. Ann Surg. 2001;234:279-89.

29. Schauer PR, Ikramuddin S, Gourash W, et al. Outcomes after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2000;232:515-29.

30. Hagedorn JC, Encarnacion B, Brat GA, Morton JM. Does gastric bypass alter alcohol metabolism? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:543-8.

31. Sjöström L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2683-93.

32. Foster A, Laws HL, Gonzalez QH, Clements RH. Gastrointestinal symptomatic outcome after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:750-3.

33. Frezza EE, Ikramuddin S, Gourash W, et al. Symptomatic improvement in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) following laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1027-31.

34. Perry Y, Courcoulas AP, Fernando HC, et al. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for recalcitrant gastroesophageal reflux disease in morbidly obese patients. JSLS. 2004;8:19-23.

35. Raftopoulos I, Awais O, Courcoulas AP, Luketich JD. Laparoscopic gastric bypass after antireflux surgery for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux in morbidly obese patients: Initial experience. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1373-80.

36. Abrams GA, Kunde SS, Lazenby AJ, Clements RH. Portal fibrosis and hepatic steatosis in morbidly obese subjects: A spectrum of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2004;40:475-83.

37. Dixon JB, Bhathal PS, O’Brien PE. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Predictors of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis in the severely obese. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:91-100.

38. Barker KB, Palekar NA, Bowers SP, et al. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: effect of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:368-73.

39. Wanless IR, Lentz JS. Fatty liver hepatitis (steatohepatitis) and obesity: An autopsy study with analysis of risk factors. Hepatology. 1990;12:1106-10.

40. Klein S, Mittendorfer B, Eagon JC, et al. Gastric bypass surgery improves metabolic and hepatic abnormalities associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1564-72.

41. Liu X, Lazenby AJ, Clements RH, et al. Resolution of nonalcoholic steatohepatits after gastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg. 2007;17:486-92.

42. Inge TH, Krebs NF, Garcia VF, et al. Bariatric surgery for severely overweight adolescents: Concerns and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2004;114:217-23.

43. Dallal RM, Bailey LA. Ulcer disease after gastric bypass surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:455-9.

44. Higa KD, Boone KB, Ho T. Complications of the laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 1,040 patients—what have we learned? Obes Surg. 2000;10:509-13.

45. Felix EL, Kettelle J, Mobley E, Swartz D. Perforated marginal ulcers after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2128-32.

46. Sacks BC, Mattar SG, Qureshi FG, et al. Incidence of marginal ulcers and the use of absorbable anastomotic sutures in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:11-16.

47. Rasmussen JJ, Fuller W, Ali MR. Marginal ulceration after laparoscopic gastric bypass: An analysis of predisposing factors in 260 patients. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1090-4.

48. Bloomberg RD, Fleishman A, Nalle JE, et al. Nutritional deficiencies following bariatric surgery: What have we learned? Obes Surg. 2005;15:145-54.

49. Skroubis G, Sakellaropoulos G, Pouggouras K, et al. Comparison of nutritional deficiencies after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and after biliopancreatic diversion with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2002;12:551-8.

50. Coupaye M, Puchaux K, Bogard C, et al. Nutritional consequences of adjustable gastric banding and gastric bypass: A 1-year prospective study. Obes Surg. 2009;19:56-65.

51. Marcuard SP, Sinar DR, Swanson MS, et al. Absence of luminal intrinsic factor after gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:1238-42.

52. Cooper PL, Brearley LK, Jamieson AC, Ball MJ. Nutritional consequences of modified vertical gastroplasty in obese subjects. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23:382-8.

53. Aasheim ET. Wernicke encephalopathy after bariatric surgery: A systematic review. Ann Surg. 2008;248:714-20.

54. Gustavsson S, Westling A. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: Complications and side effects responsible for the poor long-term outcome. Semin Laparosc Surg. 2002;9:115-24.

55. Facchiano E, Scaringi S, Sabate JM, et al. Is esophageal dysmotility after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding reversible? Obes Surg. 2007;17:832-5.

56. Shiffman ML, Sugerman HJ, Kellum JM, et al. Gallstone formation after rapid weight loss: A prospective study in patients undergoing gastric bypass surgery for treatment of morbid obesity. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:1000-5.

57. Sugerman HJ, Brewer WH, Shiffman ML, et al. A multicenter, placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, prospective trial of prophylactic ursodiol for the prevention of gallstone formation following gastric-bypass-induced rapid weight loss. Am J Surg. 1995;169:91-6.

58. Williams DB, Hagedorn JC, Lawson EH, et al. Gastric bypass reduces biochemical cardiac risk factors. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:8-13.

59. Benotti PN, Wood GC, Rodriguez H, et al. Perioperative outcomes and risk factors in gastric surgery for morbid obesity: A 9-year experience. Surgery. 2006;139:340-6.

60. Livingston EH, Huerta S, Arthur D, et al. Male gender is a predictor of morbidity and age a predictor of mortality for patients undergoing gastric bypass surgery. Ann Surg. 2002;236:576-82.

61. Livingston EH, Langert J. The impact of age and Medicare status on bariatric surgical outcomes. Arch Surg. 2006;141:1115-20.

62. Morton J, Hagedorn J, Encarnacion B, et al. Postoperative gastric bypass complications do not affect weight loss. Presented at the 11th Annual IFSO Meeting, Sydney, Australia, August 2006.

63. Wolfe BM, Morton JM. Weighing in on bariatric surgery: Procedure use, readmission rates, and mortality. JAMA. 2005;294:1960-3.

64. Nguyen NT, Paya M, Stevens CM, et al. The relationship between hospital volume and outcome in bariatric surgery at academic medical centers. Ann Surg. 2004;240:586-93.

65. Poulose BK, Griffin MR, Zhu Y, et al. National analysis of adverse patient safety for events in bariatric surgery. Am Surg. 2005;71:406-13.

66. Livingston EH, Ko CY. Assessing the relative contribution of individual risk factors on surgical outcome for gastric bypass surgery: a baseline probability analysis. J Surg Res. 2002;105:48-52.

67. Nguyen NT, Morton JM, Wolfe BM, et al. The SAGES Bariatric Surgery Outcome Initiative. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1429-38.