CHAPTER 82 Bacterial, Parasitic, and Fungal Infections of the Liver, Including Liver Abscess

Lawrence S. Friedman served as an author of this chapter on previous editions of this textbook.

The liver serves as the initial site of filtration of absorbed intestinal luminal contents and is particularly susceptible to contact with microbial antigens of all varieties. In addition to infection by viruses (see Chapters 77 to 81), the liver can be affected by (1) spread of bacterial or parasitic infection from outside the liver; (2) primary infection by spirochetal, protozoal, helminthic, or fungal organisms; or (3) systemic effects of bacterial or granulomatous infections.

BACTERIAL INFECTIONS INVOLVING OR AFFECTING THE LIVER

GRAM-POSITIVE AND GRAM-NEGATIVE BACTERIA

Toxic Shock Syndrome: Staphylococcus aureus or Group A Streptococci

Toxic shock syndrome is a multisystem disease caused by toxic shock syndrome toxins, which are superantigens that cause T cell activation and massive cytokine release. Originally described in association with serious infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus, this syndrome is now more frequently a complication of group A streptococcal infections, particularly necrotizing fasciitis.1 Risk factors for S. aureus toxic shock syndrome include tampon use and surgical wound infection. Typical findings include a scarlatiniform rash, mucosal hyperemia, hypotension, vomiting, and diarrhea.2 Hepatic involvement is almost always present and can range from elevations of serum aminotransferase levels to jaundice and extensive necrosis. Histologic findings in the liver include microabscesses and granulomas. The diagnosis is confirmed by culture of toxigenic Streptococcus pyogenes or S. aureus from the wound, blood, or other body sites. For wound infections or necrotizing fasciitis, surgical intervention is critical. Clindamycin, in conjunction with another active agent, is recommended to interfere with bacterial toxin production. Antibiotics effective against S. aureus include nafcillin for methicillin-sensitive isolates and vancomycin or linezolid for methicillin-resistant isolates, whereas penicillin remains active against S. pyogenes. Intravenous immunoglobulin may have a benefit in the setting of toxic shock associated with S. pyogenes.3

Clostridia

Clostridial myonecrosis involving Clostridium perfringens usually is a mixed anaerobic infection that results in the rapid development of local wound pain, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. The skin lesions become discolored and even bullous, and gas gangrene spreads rapidly, leading to a high mortality rate. Jaundice may develop in up to 20% of patients with gas gangrene and is predominantly a consequence of massive intravascular hemolysis caused by an exotoxin elaborated by the bacterium.4 Evidence of liver involvement may include abscess formation and gas in the portal vein. Hepatic involvement does not appear to affect mortality. The presence of clostridial bacteria portends a poor prognosis in persons with cirrhosis.5 Surgical débridement with wide excision is essential; penicillin and clindamycin are effective antibiotics.

Actinomyces

Actinomycosis is caused most commonly by Actinomyces israelii, a gram-positive anaerobic bacterium. Although cervicofacial infection is the most frequent manifestation of actinomycotic infection, gastrointestinal involvement occurs in 13% to 60% of patients.6,7 Hepatic involvement is present in 15% of cases of abdominal actinomycosis and is believed to result from metastatic spread from other abdominal sites. Common presenting manifestations of actinomycotic liver abscess include fever, abdominal pain, and anorexia with weight loss.8,9 The course is more indolent than that seen with the usual causes of pyogenic hepatic abscess and thus may be mistaken for a tumor.8 Fistula formation and invasion of other surrounding tissues such as the pleural space can occur. Anemia, leukocytosis, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and an elevated serum alkaline phosphatase level are nearly universal. Radiographic findings are nonspecific; multiple abscesses may be seen in both lobes of the liver.

The diagnosis is based on aspiration of an abscess cavity and either visualization of characteristic sulfur granules or positive results on an anaerobic culture. Most abscesses resolve with prolonged courses of intravenous penicillin or oral tetracycline. Large abscesses can be drained percutaneously or resected surgically.10

Listeria

Hepatic invasion in adult human Listeria monocytogenes infection is uncommon. One report described thirty-four cases of listeriosis involving the liver, ranging from solitary to multiple abscesses and acute and granulomatous hepatitis.11 Hepatic histologic features include multiple abscesses and granulomas. Predisposing conditions include immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, and underlying liver disease, including cirrhosis, hemochromatosis, or chronic hepatitis. The diagnosis of disseminated listerial infection is based on a positive culture result from blood or isolation from an aspirate in the case of a liver abscess. Treatment is with ampicillin or penicillin, often with gentamicin for synergy.12

Shigella and Salmonella

Several case reports have described cholestatic hepatitis attributable to enteric infection with Shigella.13,14 Histologic findings in the liver have included portal and periportal infiltration with polymorphonuclear neutrophils, hepatocyte necrosis, and cholestasis.

Typhoid fever, caused by Salmonella typhi, is a systemic infection that frequently involves the liver. Elevation of serum aminotransferase levels is common, whereas the serum bilirubin level may rise in a minority of cases.15 Some patients may present with an acute hepatitis-like picture, characterized by fever and tender hepatomegaly.16 Cholecystitis and liver abscess may complicate hepatic involvement with S. typhi infection.17

Hepatic damage by S. typhi appears to be mediated by bacterial endotoxin, although organisms can be visualized within the liver tissue. Endotoxin may produce focal necrosis, a periportal mononuclear infiltrate, and Kupffer cell hyperplasia in the liver. These changes resemble those seen in gram-negative sepsis. Characteristic typhoid nodules scattered throughout the liver are the result of profound hypertrophy and proliferation of Kupffer cells. The clinical course can be severe, with a mortality rate approaching 20%, particularly with delayed treatment or in patients with other complications of Salmonella infection. The suggestion has been made that severe typhoid fever with jaundice and encephalopathy can be differentiated from acute liver failure by the presence of an elevated serum alkaline phosphatase level, mild hypoprothrombinemia, thrombocytopenia, hepatomegaly, and an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level greater than the alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level.18 Ciprofloxacin and ceftriaxone are first-line agents for the treatment of typhoid fever.

S. paratyphi A and B (Salmonella enterica serotypes paratyphi A and B) are the predominant causes of paratyphoid fever. As in typhoid fever, abnormalities in liver biochemical tests, particularly serum aminotransferase levels, with or without hepatomegaly, are common.19 Liver abscess is a rare complication.20 Treatment is with a third-generation cephalosporin or a fluoroquinolone.

Yersinia

The subacute septicemic form of the disease resembles typhoid fever or malaria. Multiple abscesses are distributed diffusely in the liver and spleen. In some cases, the occurrence of Y. enterocolitica liver abscesses may lead to the detection of underlying hemochromatosis.21,22 The mortality rate is approximately 50%. Fluoroquinolones are the preferred antibiotics.

Gonococci

In approximately 50% of patients with disseminated gonococcal infection, serum alkaline phosphatase levels are elevated, and in 30% to 40% of patients, AST levels are elevated.23 Jaundice is uncommon.

The most common hepatic complication of gonococcal infection is the Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome, a perihepatitis that is believed to result from direct spread of the infection from the pelvis (see later).23 Clinically, patients describe a sudden, sharp pain in the right upper quadrant. The pain may be confused with that of acute cholecystitis or pleurisy. Most patients have a history of pelvic inflammatory disease. The syndrome is distinguished from gonococcal bacteremia by a characteristic friction rub over the liver and negative blood culture results. The diagnosis is made by vaginal culture for gonococci. The overall prognosis of gonococcal infection appears to be unaffected by the presence of perihepatitis.24 Ceftriaxone is the antibiotic of choice.

Legionella

Legionella pneumophila, a fastidious gram-negative bacterium, is the cause of Legionnaires’ disease. Although pneumonia is the predominant clinical manifestation, abnormal liver biochemical test results are frequent, with elevations in serum aminotransferase levels in 50%, alkaline phosphatase levels in 45%, and bilirubin levels in 20% of cases (but usually without jaundice). Involvement of the liver does not influence clinical outcome. Liver histologic changes include microvesicular steatosis and focal necrosis; organisms can be seen occasionally. The diagnosis is confirmed by direct fluorescence of antibody in the serum or sputum or of antigen in the urine.25 The antibiotic of choice is azithromycin or a fluoroquinolone.

Burkholderia pseudomallei (Melioidosis)

Burkholderia pseudomallei is a soil-borne and water-borne gram-negative bacterium that is found predominantly in Southeast Asia. The clinical spectrum of melioidosis ranges from asymptomatic infection to fulminant septicemia with involvement of the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, and liver. Histologic changes in the liver include inflammatory infiltrates, multiple microabscesses, and focal necrosis. Organisms can be visualized with a Giemsa stain of a liver biopsy specimen.26 With chronic disease, granulomas may be seen. Some liver abscesses may demonstrate a “honeycombing” appearance on computed tomography.27 Abscesses may need to be drained or débrided, and ceftazidime or meropenem is the initial drug of choice followed by a prolonged course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, with or without doxycycline.28

Brucella

Brucellosis may be acquired from infected pigs, cattle, goats, and sheep (Brucella suis, Brucella abortus, Brucella melitensis, and Brucella ovis, respectively) and typically manifests as an acute febrile illness. Hepatic abnormalities are seen in a majority of infected persons, and jaundice may be present in severe cases. Typically, multiple noncaseating hepatic granulomas are found in liver biopsy specimens; less often, focal mononuclear infiltration of the portal tracts or lobules is seen.29 Rarely, brucellosis also may produce hepatosplenic abscesses.30,31 The diagnosis can be made by isolation of the organism from a cultured specimen of liver tissue and is confirmed by serologic testing in combination with a history of exposure to animals. Surgical drainage may be required for management of Brucella abscesses. The combination of streptomycin and doxycycline is the most effective antimicrobial therapy.

Coxiella burnetii (Q Fever)

Infection by Coxiella burnetii, typically acquired by inhalation of animal dusts, causes the clinical syndrome of Q fever, which is characterized by relapsing fevers, headache, myalgias, malaise, pneumonitis, and culture-negative endocarditis. Liver involvement is common.32 The predominant abnormality is an elevated serum alkaline phosphatase level, with minimal elevations of AST or bilirubin levels. The histologic hallmark in the liver is the presence of characteristic fibrin ring granulomas. The diagnosis is confirmed by serologic testing for complement-fixing antibodies.33 Treatment with doxycycline usually is effective.

Bartonella (Oroya Fever)

Endemic to Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, Bartonella bacilliformis is a gram-negative coccobacillus that causes an acute febrile illness accompanied by jaundice, hemolysis, hepatosplenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy. Centrilobular necrosis of the liver and splenic infarction may occur. As many as 40% of patients die of sepsis or hemolysis. Prompt treatment with chloramphenicol in combination with penicillin, clindamycin, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prevents fatal complications.34

Bacillary Angiomatosis and the Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

Bacillary angiomatosis is an infectious disorder that primarily affects persons with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) or other immunodeficiency states. The causative agents have been identified as the gram-negative bacilli Bartonella henselae and, in some cases, Bartonella quintana.35 Infection frequently is associated with exposure to cats.

Bacillary angiomatosis is characterized most commonly by multiple blood-red papular skin lesions, but disseminated infection with or without skin involvement also has been described.36 The causative bacilli can infect liver, lymph nodes, pleura, bronchi, bones, brain, bone marrow, and spleen. Additional manifestations include persistent fever, bacteremia, and sepsis. Hepatic infection should be suspected when serum aminotransferase levels are elevated in the absence of other explanations.

Hepatic infection in persons with bacillary angiomatosis may manifest as peliosis hepatis, or blood-filled cysts (see Chapter 83). Histologically, peliosis in patients with AIDS is characterized by an inflammatory myxoid stroma containing clumps of bacilli and dilated capillaries surrounding the blood-filled peliotic cysts. Increasingly, diagnosis of Bartonella infection is by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methods.37 Bacillary angiomatosis responds uniformly to therapy with erythromycin. For visceral infection, prolonged treatment with erythromycin or doxycycline should be administered.38

Bacterial Sepsis and Jaundice

Jaundice may complicate systemic sepsis caused by gram-negative or gram-positive organisms. Exotoxins and endotoxin liberated in overwhelming infection can directly or indirectly, through cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), inhibit the transport of bile acids and other organic anions across the hepatic sinusoidal and bile canalicular membranes, thereby leading to intrahepatic cholestasis (see Chapter 20).39 Serum bilirubin levels can reach 15 mg/dL or higher. The magnitude of the jaundice does not correlate with mortality. Results of cultures of liver biopsy specimens usually are negative.

CHLAMYDIA

Fitz-Hugh–Curtis Syndrome

Although perihepatitis was first associated with gonococcal salpingo-oophoritis (see earlier), it is now most frequently associated with Chlamydia trachomatis infection.40 The presentation is similar to perihepatitis caused by gonococcal infection, with right upper quadrant pain accompanying a urogenital infection such as pelvic inflammatory disease. The diagnosis can be made by direct visualization at laparoscopy or laparotomy and supported by pathologic demonstration of endometritis, salpingitis, and microbiologic detection of C. trachomatis in the genital tract. Liver biochemical test results are generally normal. The treatment of choice is a single dose of azithromycin or seven days of doxycycline.

RICKETTSIA

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

Mortality from Rocky Mountain spotted fever, a systemic tick-borne rickettsial illness, has decreased considerably as a result of prompt recognition of the classic maculopapular rash in association with fever and an exposure history. A small subset of patients, however, present with multiorgan manifestations and have a high mortality rate.41 A characteristic severe vasculitis develops in these patients and is believed to be the result of a microbe-induced coagulopathy. Hepatic involvement is frequent in multiorgan disease. In one postmortem study, rickettsiae were identified in the portal triads of eight of nine fatal cases. Portal tract inflammation, portal vasculitis, and sinusoidal erythrophagocytosis were consistent findings, but hepatic necrosis was negligible. The predominant clinical manifestation was jaundice; elevations of serum aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase levels varied. Jaundice probably results from a combination of inflammatory bile ductular obstruction and hemolysis and is associated with increased mortality.32,42

Ehrlichia

Ehrlichiae are rickettsiae that parasitize leukocytes. In the United States, human monocytic ehrlichiosis is caused principally by Ehrlichia chaffeensis and, less often, by Ehrlichia canis. Human granulocytic anaplasmosis (formerly known as human granulocytic ehrlichiosis) is caused by Anaplasma phagocytophilum.32,43 In contrast with Rocky Mountain spotted fever, a rash is often absent. Hepatic involvement is seen in greater than 80% of cases, usually in the form of mild, transient serum aminotransferase elevations. More marked aminotransferase elevations may occur occasionally, in association with cholestasis, hepatosplenomegaly, and liver failure. Liver injury is attributable to proliferation of organisms within hepatocytes and provocation of an immune response. Focal necrosis, fibrin ring granulomas, and cholestatic hepatitis can be observed. A mixed portal tract infiltrate and lymphoid sinusoidal infiltrate usually are seen. The disease generally resolves with appropriate antibiotic therapy with doxycycline.44

SPIROCHETES

Leptospirosis

Anicteric leptospirosis accounts for more than 90% of cases and is characterized by a biphasic illness. The first phase begins, often abruptly, with viral illness-like symptoms associated with fever, leptospiremia, and conjunctival suffusion, which serves as an important diagnostic clue. Following a brief period of improvement, the second phase in 95% of cases is characterized by myalgias, nausea, vomiting, abdominal tenderness, and, in some cases, aseptic meningitis.45 During this phase, a few patients have elevated serum aminotransferase and bilirubin levels with hepatomegaly.

Weil’s syndrome is a severe icteric form of leptospirosis and constitutes 5% to 10% of all cases. The first phase of this illness often is marked by jaundice, which may last for weeks. During the second phase, fever may be high, and hepatic and renal manifestations predominate. Jaundice may be marked, with serum bilirubin levels approaching 30 mg/dL (predominantly conjugated). Serum aminotransferase levels usually do not exceed five times the upper limit of normal.46 Acute tubular necrosis often develops and can lead to renal failure, which may be fatal. Hemorrhagic complications are frequent and are the result of capillary injury caused by immune complexes.45 Spirochetes are seen in renal tubules in a majority of autopsy specimens but rarely are found in the liver. Hepatic histologic findings generally are nonspecific and do not include necrosis. Altered mitochondria and disrupted membranes in hepatocytes on electron microscopy suggest the possibility of a toxin-mediated injury.

Syphilis

Secondary Syphilis

Liver involvement is characteristic of secondary syphilis.47 The frequency of hepatitis in secondary syphilis ranges from 1% to 50%.47,48 Symptoms and signs usually are nonspecific, including anorexia, weight loss, fever, malaise, and sore throat. A characteristic pruritic maculopapular rash involves the palms and soles. Jaundice, hepatomegaly, and tenderness in the right upper quadrant are less common. Almost all patients exhibit generalized lymphadenopathy. Biochemical testing generally reveals low-grade elevations of serum aminotransferase and bilirubin levels, with a disproportionate elevation of the serum alkaline phosphatase level; isolated elevation of the alkaline phosphatase is common.49 Proteinuria may be present.

Histologic examination of the liver in syphilitic hepatitis generally discloses focal necrosis in the periportal and centrilobular regions. The inflammatory infiltrate typically includes polymorphonuclear neutrophils, plasma cells, lymphocytes, eosinophils, and mast cells.47,48 Kupffer cell hyperplasia may be seen, but bile ductule injury is rare. Granulomas may be seen. Spirochetes may be demonstrated by silver staining in as many as 50% of patients. Resolution of these findings without sequelae follows treatment with penicillin.

Tertiary (Late) Syphilis

Tertiary syphilis is now rare. Although hepatic lesions are common in late syphilis, most patients are asymptomatic. Some patients describe anorexia, weight loss, fatigue, fever, or abdominal pain. The characteristic hepatic lesion in tertiary syphilis is the gumma, which can be single or multiple. It is necrotic centrally, with surrounding granulation tissue consisting of a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and endarteritis; exuberant deposition of scar tissue may occur, giving the liver a lobulated appearance (hepar lobatum). If hepatic involvement is unrecognized, hepatocellular dysfunction and portal hypertension with jaundice, ascites, and gastroesophageal varices can ensue. Hepatic gummas may resolve after therapy with penicillin.50

Lyme Disease

Lyme disease is a multisystem disease caused by the tick-borne spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Predominant manifestations are dermatologic, cardiac, neurologic, and musculoskeletal. Hepatic involvement has been described. Among 314 patients, abnormal liver biochemical test results with generally increased serum aminotransferase and lactate dehydrogenase levels were seen in 19%.51 Clinical findings included anorexia, nausea and vomiting, weight loss, right upper quadrant pain, and hepatomegaly, usually within days to weeks of the onset of illness and often accompanied by the sentinel rash, erythema migrans.52

In early stages of the illness, the spirochetes are believed to disseminate hematogenously from the skin to other organs, including the liver.53 One report has suggested that the Lyme spirochete also can cause acute hepatitis as a manifestation of reactivation,54 although the possibility of reinfection cannot be fully excluded. Histologic examination of the liver in Lyme hepatitis reveals hepatocyte ballooning, marked mitotic activity, microvesicular fat, Kupffer cell hyperplasia, a mixed sinusoidal infiltrate, and intraparenchymal and sinusoidal spirochetes.53

The diagnosis of Lyme disease is confirmed with serologic studies in patients with a typical clinical history. Hepatic involvement tends to be more frequent in disseminated disease but does not appear to affect overall outcome, which is excellent in primary disease after institution of treatment with oral doxycycline, amoxicillin, clarithromycin, or azithromycin.55 Ceftriaxone is the drug of choice for late disease.44,53

TUBERCULOSIS AND OTHER MYCOBACTERIA

Granulomas are found in liver biopsy specimens in approximately 25% of persons with pulmonary tuberculosis and 80% of those with extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Tuberculous granulomas can be distinguished from sarcoid granulomas by central caseation, acid-fast bacilli, and the presence of fewer granulomas, with a tendency to coalesce.56 Multiple granulomas in the liver also may be seen following vaccination with bacille Calmette-Guérin, especially in persons with an impaired immune response. Patients with multiple granulomas caused by tuberculosis rarely have clinically significant liver disease. Occasionally, tender hepatomegaly is found. Jaundice with elevated serum alkaline phosphatase levels may occur in miliary infection. The treatment of tuberculous granulomatous disease of the liver is the same as that for active pulmonary tuberculosis—namely, four-drug therapy.56 Hepatic involvement in Mycobacterium avium complex infection is discussed in Chapter 33.

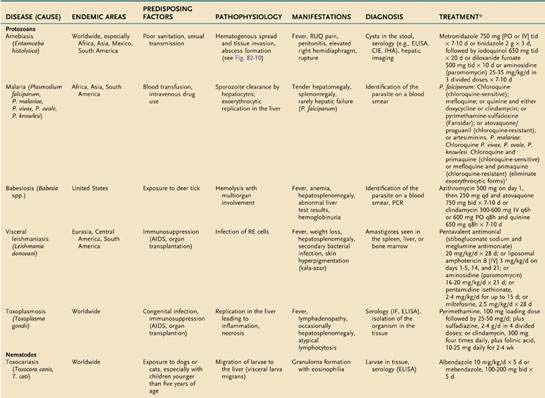

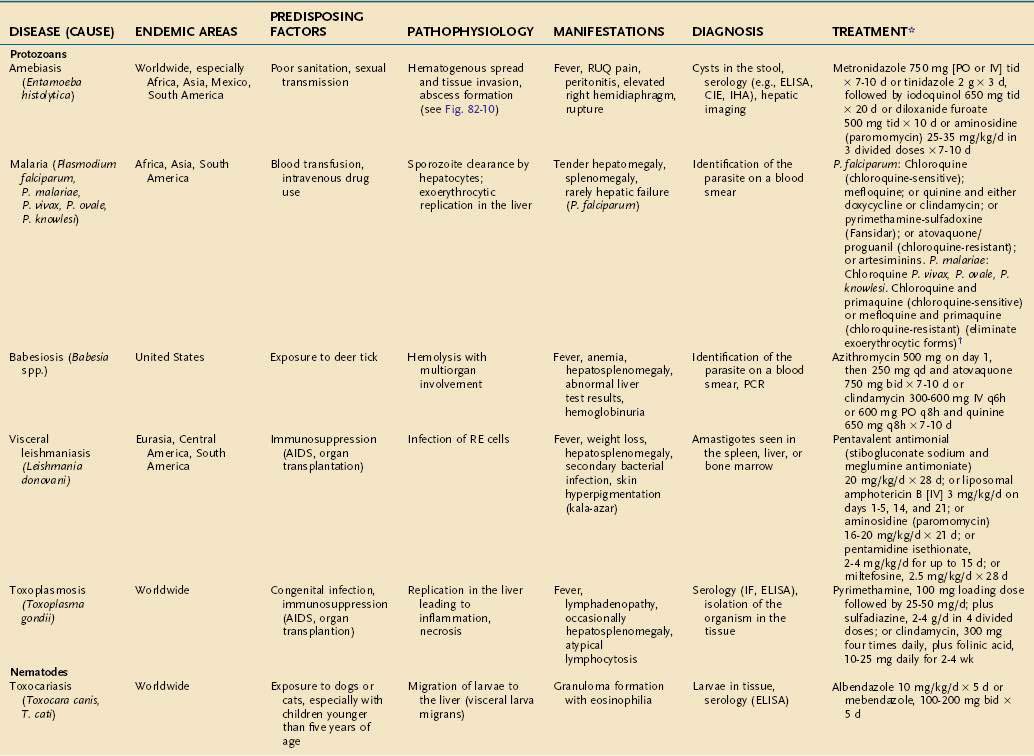

PARASITES (Tables 82-1 and 82-2)

Table 82-1 Parasitic Infections of the Liver and Biliary Tract: Classification by Pathologic Process

| PATHOLOGIC PROCESS | DISEASES |

|---|---|

| Liver Disease | |

| Granulomatous hepatitis | Capillariasis |

| Fascioliasis | |

| Schistosomiasis | |

| Strongyloidiasis | |

| Toxocariasis | |

| Portal fibrosis | Schistosomiasis |

| Hepatic abscess or necrosis | Amebic abscess |

| Toxoplasmosis | |

| Cystic liver disease | Echinococcosis |

| Peliosis hepatis | Bacillary angiomatosis |

| Reticuloendothelial Disease | |

| Kupffer cell infection or hyperplasia | Babesiosis |

| Malaria | |

| Toxoplasmosis | |

| Visceral leishmaniasis | |

| Biliary Tract Disease | |

| Cholangitis | Clonorchiasis/opisthorchiasis |

| Fascioliasis | |

| Biliary hyperplasia | Ascariasis |

| Clonorchiasis | |

| Cryptosporidiosis | |

| Fascioliasis | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | Clonorchiasis/opisthorchiasis |

PROTOZOA (see also Chapter 109)

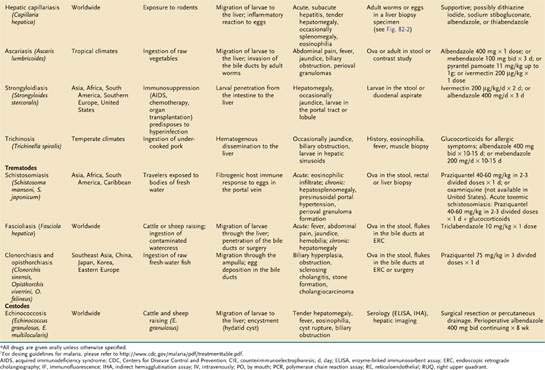

Malaria

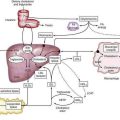

An estimated 300 to 500 million persons in more than 100 countries are infected with malaria each year. The liver is affected during two stages of the malarial life cycle: first in the pre-erythrocytic phase, and then in the erythrocytic phase, which coincides with clinical illness. The life cycle of the prototypical malarial parasite is illustrated in Figure 82-1.

Pathobiology of the Plasmodium Life Cycle

Malarial sporozoites injected by an infected mosquito circulate to the liver and enter hepatocytes. Maturation to schizonts ensues. When the schizont ruptures, merozoites are released into the bloodstream, where they enter erythrocytes. The major species of Plasmodium responsible for malaria differ with respect to the number of merozoites released and the maturation times. Infection by Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium malariae is not associated with a residual liver stage after the release of merozoites, whereas infection by Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium ovale is associated with a persistent exoerythrocytic stage, the hypnozoite, which persists in the liver and, when activated, can divide and mature into schizont forms. Plasmodium knowlesi has been identified as a fifth species capable of infecting humans and occasionally results in severe manifestations including jaundice, hepatic dysfunction, and acute kidney injury.57

The extent of hepatic injury varies with the malarial species (most severe with P. falciparum) and the severity of infection. Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia most commonly is seen as a result of hemolysis, but hepatocellular dysfunction is also possible, leading to conjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Moderate elevations of serum aminotransferase and 5′-nucleotidase levels may be observed.58 Synthetic dysfunction (e.g., prolongation of the prothrombin time, hypoalbuminemia) may be seen as well. In severe falciparum malaria, hypoglycemia and lactic acidosis are late and life-threatening complications.59 Reversible reductions in portal venous blood flow have been described during the acute phase of falciparum malaria, presumably as a consequence of micro-occlusion of portal venous branches by parasitized erythrocytes.59

Histopathologic Features

In acute falciparum malaria in a previously unexposed person, hepatic macrophages hypertrophy, and large quantities of malarial pigment (the result of hemoglobin degradation by the parasite) accumulate in Kupffer cells, which phagocytose parasitized and unparasitized erythrocytes.60 Histopathologic features include Kupffer cell hyperplasia with pigment deposition and a mononuclear infiltrate. Hepatocyte swelling and centrizonal necrosis may be seen. All abnormalities are reversible with treatment.

Clinical Features

Only the erythrocytic stage of malaria is associated with clinical illness. Symptoms and signs of acute infection typically develop 30 to 60 days following exposure and include fever, which often is hectic, malaise, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and myalgias. Jaundice caused by hemolysis is common in adults, especially in heavy infection with P. falciparum. In general, hepatic failure is seen only in association with concomitant viral hepatitis or with severe P. falciparum infection.61,62 One series identified evidence of hepatic encephalopathy in 15 of 86 patients with falciparum malaria and jaundice; four cases were fatal.61 Tender hepatomegaly with splenomegaly is common. Cytopenias are common in acute infection. The differential diagnosis includes viral hepatitis, gastroenteritis, amebic liver abscess, yellow fever, typhoid, tuberculosis, and brucellosis.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of acute malaria rests on the clinical history, physical examination, and identification of parasites on peripheral thin and thick blood smears. Because the number of parasites in the blood may be small, repeated smear examinations should be performed by an experienced examiner when the index of suspicion is high. P. knowlesi may resemble P. malariae in morphology, and PCR-based tests may help distinguish these two species.57 Rapid antigen detection assays are available but are less reliable than other diagnostic approaches.63

Treatment

The treatment of acute malaria depends on the species of parasite and, for falciparum infection, the pattern of chloroquine resistance. Chloroquine generally is effective in areas endemic for chloroquine-sensitive species. Resistant falciparum infections can be treated with mefloquine alone; quinine and either doxycycline or clindamycin; pyrimethamine-sulfadoxine (Fansidar); a combination of atovaquone and proguanil; or artemisinin derivatives including artemisinin, artemether, and artesunate.64 For P. vivax and P. ovale infections, the addition of primaquine (in persons without glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency) to chloroquine or mefloquine is indicated to eliminate the exoerythrocytic hypnozoites in the liver.65

Hyperreactive Malarial Splenomegaly (Tropical Splenomegaly Syndrome)

In endemic areas, repeated exposure to malaria may lead to an aberrant immunologic response characterized by overproduction of B lymphocytes, circulating malarial antibody, and increased levels of circulating immune complexes, resulting in dense hepatic sinusoidal lymphocytosis and stimulation of the reticuloendothelial cell system. The clinical picture includes massive splenomegaly, markedly elevated antimalarial antibody levels, and high serum immunoglobulin M (IgM) levels. Severe debilitating anemia caused by hypersplenism, especially in women of childbearing age, can result.66 Variceal bleeding is uncommon but may result from portal hypertension consequent to markedly increased splenic and portal venous blood flow. Treatment consists of lifelong antimalarial therapy and blood transfusions.

Babesiosis

Babesiosis, caused by Babesia species, is a malaria-like illness transmitted by the deer tick Ixodes scapularis.67 The disease is endemic to coastal areas of the Northeast and areas of the Midwest in the United States. Clinical features include fever, anemia, mild hepatosplenomegaly, abnormalities on liver biochemical tests, hemoglobinuria, and hemophagocytosis on bone marrow biopsy specimen. The disease is especially severe in asplenic and immunocompromised patients. In rare cases, marked pancytopenia occurs. Hepatic involvement reflects the severity of the systemic illness but generally is not severe. Uncomplicated cases are treated with a combination of the following active agents: (1) oral azithromycin, 500 mg single dose followed by 250 mg once daily, plus atovaquone, 750 mg twice daily, for 7 to 10 days; or (2) oral clindamycin, 600 mg three times daily, in combination with quinine, 650 mg three times daily, for 7 to 10 days. In severe cases, the clindamycin may be given intravenously and partial or complete exchange transfusion should be considered.44

Leishmaniasis

Visceral leishmaniasis is caused by Leishmania donovani and is endemic in the Mediterranean, central Asia, the former Soviet Union, the Middle East, China, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Africa, Central America, and South America.68 This entity should be considered in returning travelers and military personnel from these areas. Amastigotes are ingested by the sand fly (Lutzomyia in the New World, Phlebotomus in the Old World) and become flagellated promastigotes. Following injection into the human host, the promastigotes are phagocytosed by macrophages in the reticuloendothelial system, where they multiply.

Histopathologic Features

In visceral leishmaniasis, organisms usually can be found in mononuclear phagocytes of the liver, spleen, bone marrow, and lymph nodes. Proliferation of Kupffer cells often is seen, and amastigotes (Leishman-Donovan bodies) can be detected within these cells.69 Occasionally, parasite-bearing cells aggregate within noncaseating granulomas.70 Hepatocyte necrosis can range in degree from mild to severe. Healing is accompanied by fibrous deposition, and occasionally the liver takes on a cirrhotic appearance. Nevertheless, complications of chronic liver disease are rare.

Clinical Features

Physical findings include hepatomegaly, massive splenomegaly, jaundice or ascites in severe disease, generalized lymphadenopathy, and muscle wasting.71 Cutaneous gray hyperpigmentation, which prompted the name kala-azar (black fever), is characteristically seen in patients in India. Oral and nasopharyngeal nodules resulting from granuloma formation also may be seen.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on the history, physical examination, and microscopic demonstration of amastigotes by a Wright or Giemsa stain of affected tissue samples. The highest yield (90%) comes from aspiration of the spleen. Liver biopsy is less risky and associated with a yield nearly as great as that of splenic aspiration. The yield of bone marrow aspirates is 80%, and that of lymph node aspirates is 60%.54 Culture requires specialized media and may take several weeks. Serologic testing (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA], immunofluorescence, direct agglutination) can be used to support a presumptive diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis but is insensitive, particularly in immunocompromised hosts.72 The leishmanin skin test (Montenegro test) is not helpful in acute visceral disease. PCR-based testing of blood or other tissue may also be useful for diagnosis as well as monitoring.73

Treatment

Pentavalent antimonial compounds are the drugs of choice for all forms of leishmaniasis. Parenteral sodium stibogluconate and meglumine antimoniate are available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for treatment of infections in the United States. Treatment with antimonials should be administered for at least four weeks. Alternative parenteral agents include liposomal amphotericin B and aminosidine (paromomycin).74 Patients with AIDS and leishmaniasis often fail to respond to or relapse following treatment with conventional regimens.72 Miltefosine, a phosphocholine analog administered orally, has shown promise in visceral leishmaniasis, with a reported cure rate of 82% to 97%.75,76

Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasmosis, caused by Toxoplasma gondii, is found worldwide. In the United States, serologic surveys suggest that exposure to T. gondii has decreased from 14% to 9% among persons ages 12 to 49.77 The infection may be transmitted congenitally or occur as an opportunistic infection that causes cerebral mass lesions in patients with AIDS. Oocysts of T. gondii in soil, water, or contaminated meat are ingested and mature in the intestinal tract of humans to become sporozoites, which penetrate the intestinal mucosa, become tachyzoites, and circulate systemically, invading a wide array of cell types.78 Hepatic involvement has been observed in severe, disseminated infection.

Clinical Features

Although most primary infections are asymptomatic, acquired toxoplasmosis can manifest as a mononucleosis-like illness with fever, chills, headache, and regional lymphadenopathy.79 Hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and minimal elevations of serum aminotransferase levels are uncommon findings.80,81 Infections of immunocompromised hosts can result in pneumonia, myocarditis, encephalitis, and, rarely, hepatitis.78,82 Toxoplasmosis can produce atypical lymphocytosis, an otherwise unusual feature of parasitic disease.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is best made by detecting specific IgM or IgG antibody using highly specific indirect immunofluorescence or an enzyme immunoassay.83 Specialized histologic staining techniques and tissue culture systems can provide adjunctive diagnostic support. PCR analysis of serum and liver also can be helpful in ambiguous cases.84

Treatment

Antibiotic therapy should be administered to all persons with severe symptomatic infection and to immunocompromised or pregnant patients with acute uncomplicated infection. Treatment consists of a combination of pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine, plus folinic acid to minimize hematologic toxicity, for two to four weeks.78

HELMINTHS (see also Chapter 110)

Nematodes (Roundworms)

Toxocariasis

Toxocara canis and Toxocara cati infect dogs and cats, respectively. Infection occurs worldwide, especially in children, and is acquired when embryonated eggs are ingested in soil or contaminated food. The eggs hatch in the small intestine and release larvae that penetrate the intestinal wall, enter the portal venous circulation, and reach the liver and systemic circulation. Blocked by narrowing vascular channels, the immature worms bore through vessel walls and migrate through the tissues, where they cause hemorrhagic, necrotic, and secondary inflammatory responses. When larvae become trapped in tissue, they provoke granuloma formation with a predominance of eosinophils. Tissue larvae may remain in inflammatory capsules or granulomas for months to years. The liver, brain, and eye are affected most frequently.85

Clinical Features

Most infected persons are asymptomatic. Two clinical syndromes are recognized (1) visceral larva migrans and (2) “occult” infections associated with nonspecific symptoms, including abdominal pain, anorexia, fever, and wheezing.85

Visceral larva migrans is seen most commonly in children with a history of pica. Findings include fever, hepatomegaly, urticaria, leukocytosis with persistent eosinophilia, hypergammaglobulinemia, and elevated blood group isohemagglutinins.85 Toxocariasis has been implicated in the development of chronic cholestatic hepatitis86 as well as pyogenic liver abscess.87 Pulmonary manifestations include asthma and pneumonitis. Neurologic involvement can result in focal or generalized seizures, encephalopathy, and abnormal behavior.85 Ocular larva migrans often is associated with visual loss and strabismus and can manifest as a unilateral raised retinal lesion that resembles an ocular tumor.

Diagnosis

The possibility of toxocariasis should be considered in persons with a history of pica, exposure to dogs or cats, and persistent eosinophilia.88 Stool studies are not useful for toxocariasis because these organisms do not produce eggs in humans, nor do they remain in the gastrointestinal tract. A definitive diagnosis is made by identification of the larvae in affected tissues, although blind biopsies are not routinely recommended.85 The finding of an eosinophilic granuloma may be specific for visceral larva migrans.89 A liver biopsy may be necessary to differentiate visceral larva migrans from hepatic capillariasis (see later). A strongly positive result on an ELISA using larval antigens provides support for the diagnosis.

Treatment

Treatment is primarily supportive, as visceral larva migrans is generally self-limited. If required, antihelminthic therapy with albendazole, 10 mg/kg/day in two divided doses for five days, or mebendazole, 100 to 200 mg twice daily for five days, may be used. Severe pulmonary, cardiac, ophthalmologic, or neurologic manifestations may warrant use of systemic glucocorticoids.85

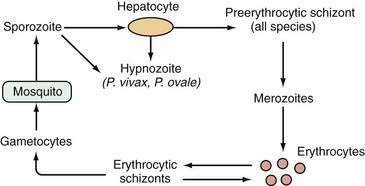

Hepatic Capillariasis

Clinical Features

Hepatic capillariasis typically manifests as acute or subacute hepatitis. Findings include fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea or constipation, anorexia, myalgias, arthralgias, tender hepatomegaly, and occasionally splenomegaly. Laboratory investigation may reveal leukocytosis with eosinophilia; mild elevations of serum AST, alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin levels; anemia; and an increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate. A chest radiograph may show pneumonitis.90

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is established by detection of adult worms or eggs in the liver (Fig. 82-2). Histologic findings in the liver include necrosis, fibrosis, and granulomas.90 A finding of C. hepatica eggs in stools is not indicative of acute infection and probably reflects passage of undercooked liver from an infected animal.

Ascariasis

Ascaris lumbricoides infects at least 1 billion persons, particularly in areas of lower socioeconomic standing.92 Humans are infected by ingesting embryonated eggs, usually adherent to raw vegetables. The eggs hatch in the small intestine, and the larvae penetrate the mucosa, enter the portal circulation, and reach the liver, pulmonary artery, and lungs; they grow in the alveolar spaces, are regurgitated and swallowed, and become mature adults in the intestine two to three months after ingestion. Then the cycle repeats itself.

Clinical Features

Symptoms generally occur in persons with a large worm burden; most infected persons are asymptomatic. Cough, fever, dyspnea, wheezing, substernal chest discomfort, and hepatomegaly may occur in the first two weeks. Chronic infection more frequently is characterized by episodic epigastric or periumbilical pain. If the worm burden is particularly heavy, small bowel complications such as obstruction, intussusception, volvulus, perforation, or appendicitis may occur.93 Fragments of disintegrating worms within the biliary tree can serve as nidi for the development of biliary calculi.94 Preexisting disease of the biliary tree or pancreatic duct can predispose the patient to migration of the worm into the bile ducts, with development of obstructive jaundice, cholangitis, or intrahepatic abscesses.92,95

Diagnosis

A history of regurgitating a worm or passing a large worm (15 to 40 cm long) in the stool suggests ascariasis. In the absence of such a history, the diagnosis is made by identification of characteristic eggs in stool specimens. Larvae also may be identified in sputum and gastric washings and in liver and lung biopsy specimens. In patients with biliary or pancreatic symptoms, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is performed. ERCP also allows extraction of the worm.96 Chest radiography may show an infiltrate, and eosinophilia may be present.

Treatment

One of the following regimens may be used: (1) a single dose of albendazole, 400 mg; (2) mebendazole, 100 mg twice daily for three days; (3) a single dose of ivermectin, 200 µg/kg; or (4) pyrantel pamoate, 11 mg/kg to a maximum of 1 g.97 Intestinal or biliary obstruction may require endoscopic or surgical intervention.

Strongyloidiasis

Strongyloides stercoralis is prevalent in the tropics and subtropics, southern and eastern Europe, and the United States. Infection usually is asymptomatic. Humans are infected by the filariform larvae, which penetrate intact skin, are carried to the lungs, migrate through the alveoli, and are swallowed to reach the intestine, where maturation ensues. Autoinfection can occur if the rhabditiform larvae transform into infective filariform larvae in the intestine; reinfection occurs by penetration of the bowel wall or perianal skin. Symptomatic infection results from a heavy infectious burden or infection in an immunocompromised patient. In the latter case, a hyperinfection syndrome may result from dissemination of filariform larvae into tissues that usually are not infected.98

Clinical Features

Acute infection can lead to a pruritic eruption, followed by fever, cough, wheezing, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and eosinophilia. In immunocompromised patients, the hyperinfection syndrome may be characterized by invasion of any organ, including the liver, lung, and brain. Hyperinfection should be considered particularly in the setting of sepsis caused by multiple organisms found in intestinal flora, a consequence of burrowing of larvae through the intestinal mucosa.99 When the liver is affected, features include jaundice and cholestatic liver biochemical test abnormalities. A liver biopsy specimen may show periportal inflammation, eosinophilic granulomatous hepatitis, or both. Larvae may be observed in intrahepatic bile canaliculi, lymphatic vessels, and small branches of the portal vein.98

Diagnosis

Serologic tests include counterimmunoelectrophoresis and ELISA and can be used for post-treatment evaluation.100 The diagnosis of active infection is firm when larvae are identified in the stool or intestinal biopsy specimens. An obstructive hepatobiliary picture in a person with known strongyloidiasis should alert the clinician to the possibility of dissemination.

Treatment

For treatment of acute infection, the drug of choice is ivermectin, 200 µg/kg/day for two days. Clearance rates are high. An alternative agent is albendazole, 400 mg/day for three days for adults and children older than two years of age, but retreatment may be necessary and this drug is less effective for disseminated disease. The hyperinfection syndrome requires longer courses of treatment than those used for the primary acute infection.101

Trichinosis

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is suggested by a characteristic history in a patient with fever and eosinophilia. Serologic assays for antibody to Trichinella may not be helpful in the acute phase of infection but can be useful after two weeks.102 Muscle biopsy may help to confirm the diagnosis. DNA-based tests are investigational.

Trematodes (Flukes)

Schistosomiasis (Bilharziasis)

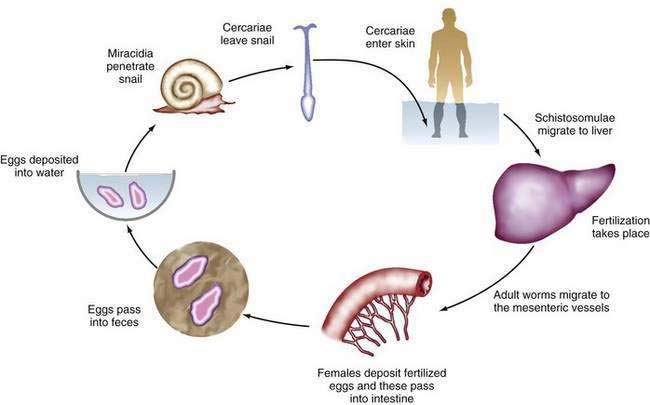

About 200 million persons worldwide are infected with trematodes of the genus Schistosoma. Schistosoma mansoni is found in the western hemisphere, Africa, and the Middle East; S. haematobium is found in Africa and the Middle East; S. japonicum and S. mekongi are found in the Far East; and S. intercalatum is found in parts of central Africa. The last two species are much less common than the other three and cause liver disease and colonic disease, respectively.103

The infectious cycle is initiated by penetration of the skin by free cercariae in fresh water (Fig. 82-3). The cercariae reach the pulmonary vessels within 24 hours, pass through the lungs, and reach the liver, where they lodge, develop into adults, and mate. Adult worms then migrate to their ultimate destinations in the inferior mesenteric venules (S. mansoni), superior mesenteric venules (S. japonicum), or veins around the bladder (S. haematobium). These locations correlate with the clinical complications associated with each species. Each female fluke can lay 300 to 3000 eggs daily. The eggs are deposited in the terminal venules and eventually migrate into the lumen of the involved organ, after which they are expelled in the stool or urine. Eggs remaining in the organ provoke a robust granulomatous response. Excreted eggs hatch immediately in fresh water and liberate early intermediate miracidia, which infect their snail hosts. The miracidia transform into cercariae within the snails and then are released into the water, from which they may again infect humans.103

Figure 82-3. The life cycle of Schistosoma species.

(From Gitlin N, Strauss R. Atlas of Clinical Hepatology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1995. p 72.)

Clinical Features

Untreated acute schistosomiasis invariably progresses to chronic disease. Mesenteric infection leads to hepatic complications, including periportal fibrosis, presinusoidal occlusion, and, ultimately, portal hypertension, as a result of the inflammatory reaction to eggs deposited in the liver. The development of periportal fibrosis appears to be related to production of TNF-α.104 The lungs and central nervous system may be affected when eggs or adult worms pass through the liver into the systemic circulation, especially in S. japonicum infection; pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale may result.105 With severe schistosomal infection, portal hypertension becomes progressive, leading to gastroesophageal varices, splenomegaly, and rarely ascites.

Chronic schistosomal infection may be complicated by increased susceptibility to Salmonella infections.106 Hepatitis B or hepatitis C viral coinfection also is common in persons living in endemic areas and may accelerate the progression of liver disease and development of hepatocellular carcinoma.107 In African intestinal schistosomiasis, pseudopolyps of the colon may develop, leading in some cases to protein-losing colopathy and formation of an inflammatory mass in the descending colon.

Diagnosis

The possibility of acute schistosomiasis should be considered in a patient with a history of exposure, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and fever. Multiple stool examinations for ova may be required to confirm the diagnosis because results frequently are negative in the early phase of disease. Serologic testing using counterimmunoelectrophoresis or ELISA cannot distinguish between past infection and active disease but may be useful in a returned traveler. Sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy may reveal rectosigmoid or transverse colon involvement and may be useful in chronic disease, when few eggs pass in the feces. Ultrasonography and liver biopsy are useful for demonstrating periportal (“pipestem” or “clay pipestem”) fibrosis (Fig. 82-4) but not for diagnosing acute infection because of their insensitivity for detecting schistosomal eggs.108 CT may show low-attenuation rings around main portal vein branches with marked enhancement.109

Treatment

Praziquantel, 40 mg/kg for S. mansoni or S. haematobium and 60 mg/kg for S. japonicum or S. mekongi given in one day in two to three divided doses four hours apart, is the therapeutic agent of choice. Oxamniquine is an effective alternative agent in patients who cannot tolerate praziquantel, but it is no longer available in the United States. Treatment of acute toxemic schistosomiasis often requires prednisone to suppress immune-mediated helminthicidal or drug reactions, in conjunction with praziquantel at the dose appropriate for the particular species for three to six days.103 Retreatment after two to three months is often necessary after Katayama fever.110

Band ligation and injection sclerotherapy of varices are effective in controlling variceal bleeding (see Chapter 90). Management of advanced chronic schistosomal liver disease may require placement of a distal splenorenal shunt or esophagogastric devascularization with splenectomy. Fortunately, since the advent of praziquantel, complicated schistosomal liver disease has become uncommon.

Fascioliasis

Fascioliasis is endemic in parts of Europe and Latin America, North Africa, Asia, the Western Pacific, and some parts of the United States. Fascioliasis is caused by the sheep liver fluke Fasciola hepatica. Eggs passed in the feces of infected mammals into fresh water give rise to miracidia that penetrate snails and eventually emerge as mobile cercariae, which attach to aquatic plants such as watercress. Hosts become infected when they consume plants containing encysted metacercariae, which then bore into the intestinal wall, enter the abdominal cavity, penetrate the hepatic capsule, and eventually settle in the bile ducts, where they attain maturity. Mature flukes release eggs that are passed in the host’s feces to complete the life cycle.111

Clinical Features

Three syndromes are recognized: acute or invasive, chronic latent, and chronic obstructive.112 The acute phase corresponds to the migration of young flukes through the liver and is marked by fever, pain in the right upper quadrant, and eosinophilia. Urticaria with dermatographia and nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms are common. Physical examination often reveals fever and a tender, enlarged liver. Splenomegaly is seen in as many as 25% of cases, but jaundice is rare and liver biochemical test abnormalities are mild.113 Eosinophilia can be profound, with eosinophils sometimes exceeding 80% of the differential leukocyte count.111

The latent phase corresponds with the settling of the flukes into the bile ducts and can last for months to years. Affected patients may experience vague gastrointestinal symptoms. Eosinophilia persists, and fever can occur.113

The chronic obstructive phase is a consequence of intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ductal inflammation and hyperplasia evoked by adult flukes. Recurrent biliary pain, cholangitis, cholelithiasis, and biliary obstruction may result. Blood loss from epithelial injury occurs, but overt hemobilia is rare. Liver biochemical testing commonly demonstrates a pattern suggestive of biliary obstruction.114 Long-term infection may lead to biliary cirrhosis and secondary sclerosing cholangitis, but no convincing association with biliary tract or hepatic malignancy has been demonstrated.115

Diagnosis

The diagnosis should be considered in a patient with prolonged fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea, tender hepatomegaly, and eosinophilia. Because eggs are not passed during the acute phase, diagnosis depends on the detection of antibody by counterimmunoelectrophoresis or ELISA. In the latent and chronic phases, a definitive diagnosis is based on the detection of eggs in stool, duodenal aspirate specimens, or bile.116 On occasion, ultrasonography or ERCP will demonstrate flukes in the gallbladder and bile duct.117 If one member of a family is diagnosed with fascioliasis, all household members should be evaluated.

Hepatic histologic findings include necrosis and granulomas with eosinophilic infiltrates and Charcot-Leyden crystals. Eosinophilic abscesses, epithelial hyperplasia of the bile ducts, and periportal fibrosis may be seen.118

Clonorchiasis and Opisthorchiasis

Clonorchis sinensis, Opisthorchis viverrini, and Opisthorchis felineus are trematodes of the family Opisthorchiidae. Infection by C. sinensis and O. viverrini is widespread in East and Southeast Asia and is linked to lower socioeconomic status. O. felineus infects humans and domestic animals in eastern Europe. All three have similar lifecycles and result in similar clinical manifestations. Eggs are passed in the feces into fresh water, consumed by snails, and hatch as free-swimming cercariae, which seek and penetrate fish or crayfish and encyst in skin or muscle as metacercariae. The mammalian host is infected when it consumes raw or undercooked fish. The metacercariae excyst in the small intestine and migrate into the ampulla of Vater and bile ducts, where they mature into adult flukes. Infection can be maintained for 2 decades or longer.116

Clinical Features

In general, acute infection is clinically silent. Occasional symptoms include fever, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Chronic manifestations correlate with the fluke burden and are dominated by hepatobiliary features: fever, pain in the right upper quadrant, tender hepatomegaly, and eosinophilia. If the worm burden in the bile ducts is heavy, chronic or intermittent biliary obstruction can ensue, with frequent cholelithiasis, cholecystitis, jaundice, and, ultimately, recurrent pyogenic cholangitis (see Chapter 68). Liver biochemical test results, especially serum alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin levels, are elevated. Long-standing infection leads to exuberant inflammation, resulting in periportal fibrosis, marked biliary epithelial hyperplasia and dysplasia, and, ultimately, a substantially increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma.116,120 Cholangiocarcinoma resulting from clonorchiasis or opisthorchiasis tends to be multicentric and arises in the secondary biliary radicles of the hilum of the liver. Cholangiocarcinoma should be suspected in infected persons with weight loss, jaundice, epigastric pain, or an abdominal mass (see Chapter 69).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of clonorchiasis or opisthorchiasis is made by detection of characteristic fluke eggs in the stool, except late in the disease when biliary obstruction has supervened. In these cases, the diagnosis is made by identifying flukes in the bile ducts or gallbladder at surgery or in bile obtained by postoperative drainage or percutaneous aspiration (Fig. 82-5). Endoscopic or intraoperative cholangiography reveals slender, uniform filling defects within intrahepatic ducts that are alternately dilated and strictured, mimicking sclerosing cholangitis. Serologic methods of diagnosis cannot distinguish between past or current infection.49,121

Treatment

All patients with clonorchiasis or opisthorchiasis should receive praziquantel, which is uniformly effective in a dose of 75 mg/kg in three divided doses over one day. Side effects are uncommon and include headache, dizziness, and nausea. After treatment, dead flukes may be seen in the stool or biliary drainage. When the burden of infecting organisms is high, the dead flukes and surrounding debris or stones may cause biliary obstruction, necessitating endoscopic or surgical drainage.115

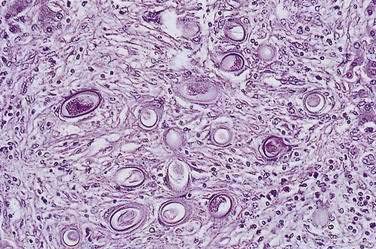

Cestodes (Tapeworms)

Echinococcosis

Clinical Features

Most patients with a hydatid cyst in the liver have no symptoms. As the cysts of E. granulosus grow within the liver (Fig. 82-6), they begin to cause low-grade fever, pain, tender hepatomegaly (usually affecting the right hepatic lobe), and eosinophilia. If the cysts grow large enough, they may rupture spontaneously or after trauma into the lungs, leading to dyspnea and hemoptysis. More extensive rupture into the peritoneum or lungs may lead to a life-threatening anaphylactic reaction to the cyst contents. Rupture into the biliary tract can cause cholangitis and obstruction; marked eosinophilia may be present. Superinfection of the hepatic cysts can lead to pyogenic liver abscesses in up to 20% of patients with hepatic disease. Rare complications of hydatid cysts or cyst rupture include pancreatitis, portal hypertension, Budd-Chiari syndrome, and rupture into the pericardial sac.

Figure 82-6. Liver resection specimen of a hydatid cyst caused by Echinococcus granulosus. Multiple daughter cysts are seen.

(Courtesy of Dr. Fiona Graeme-Cook, Boston, Mass.)

E. multilocularis is highly invasive; infection leads to formation of solid masses in the liver that are easily confused with cirrhosis or carcinoma. Alveolar hydatid disease is the term applied to hepatic nodules that appear on microscopy as alveoli-like microvesicles.122 Daughter cysts bud from the germinal membrane in an uncontrolled manner, with “invasion” of the surrounding liver parenchyma by the scolices. Infection of bile ducts and vessels and necrosis of parenchyma may result in cholangitis, liver abscess, sepsis, portal hypertension, hepatic vein occlusion, and biliary cirrhosis. Unfortunately, infection generally is not diagnosed until the lesions are inoperable because of extensive invasion or distant metastatic disease, and mortality rates are high, approaching 90%.122

Diagnosis

A history of exposure in a patient with hepatomegaly and an abdominal mass is highly suggestive of hepatic echinococcosis, but the most important diagnostic tools are radiology and serology. Ring-like calcifications in up to one fourth of hepatic cysts are visible on plain abdominal radiographs in patients infected with E. granulosus. The sensitivity and specificity of both ultrasonography and CT in confirming the diagnosis are high (Fig. 82-7).123 Both modalities can demonstrate intracystic septations and daughter cyst formation in about one half of the cysts. Contrast-enhanced CT may display avascular cysts with ring enhancement. Percutaneous aspiration of the cyst had traditionally been discouraged because of concern about anaphylactic reactions. Encouraging reports, however, suggest that under carefully controlled conditions, with use of thin needles and concomitant antihelminthic therapy, percutaneous aspiration for diagnosis and therapy may be safe.124,125 The detection of protoscolices or acid-fast hooklets in the cyst fluid confirms the diagnosis.126 An ELISA is the best serologic assay for diagnosis, with a sensitivity rate of 84% to 90%.127 Assays for detecting circulating antigen are likely to provide additional diagnostic benefit in the future. The Casoni skin test, used in the past, is nonspecific and no longer recommended.

Treatment

Promising data indicate that careful percutaneous drainage is a safe and effective alternative to surgery for the treatment of complicated cysts.128 In addition to surgery or drainage, administration of an antihelminthic, such as albendazole, 10 mg/kg/day for eight weeks, is recommended.129Puncture, aspiration, injection (of a scolicidal agent), and re-aspiration (PAIR) can be performed safely with long-term control of echinococcal cysts.125 Injection of hydatid liver cysts with albendazole has also been described.124 Therefore, nonsurgical approaches are now available for management of hydatid cysts. The decision between surgical and nonsurgical techniques depends on the extent and type of lesions.130 Cysts that cannot be treated surgically or percutaneously should be treated with albendazole, preferably, or mebendazole. Large doses and prolonged treatment are required (e.g., albendazole 10 mg/kg daily in two divided doses for 28 days, repeated three or four times, with 2-week breaks between courses).

Surgical resection is curative in up to one third of cases of E. multilocularis infection. In most cases the disease is advanced when the diagnosis is made. In such cases, palliative drainage procedures or long-term treatment with albendazole or other benzimidazole carbamates may prolong survival.122,131 Surgery appears to be the most effective approach for management of E. vogeli infection.

FUNGI

CANDIDIASIS

Candida species may cause invasive systemic infection with hepatic involvement in severely immunocompromised persons (see Chapters 33 and 34). The liver can become infected by C. albicans and related species in the setting of disseminated, multiorgan disease. Most disseminated infections occur in leukemic patients undergoing high-dose chemotherapy and become clinically evident during the period of recovery from severe neutropenia. In several series, hepatic candidiasis was present in 51% to 91% of predominantly leukemic patients with disseminated candidiasis.132,133 Disease often is overwhelming, with high mortality rates.133

Other, less frequent presentations in the compromised host include isolated or focal hepatic or hepatosplenic candidiasis.134 Focal candidiasis is believed to result from colonization of the gastrointestinal tract by Candida, which disseminates locally following the onset of neutropenia and mucosal injury caused by high-dose chemotherapy.134 Resulting fungemia of the portal vein seeds the liver and leads to formation of hepatic microabscesses and macroabscesses.

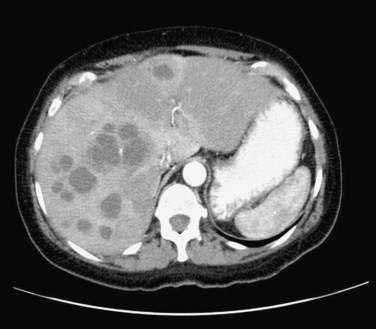

In either focal or disseminated candidiasis involving the liver, clinical features include fever, abdominal pain and distention, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and tender hepatomegaly. The serum alkaline phosphatase level is almost invariably elevated, with varying elevations in serum aminotransferase and bilirubin levels. CT of the abdomen is the most sensitive test to detect hepatic or splenic abscesses, which often are multicentric (Fig. 82-8).135 In cases diagnosed antemortem, liver biopsy or laparoscopy reveals macroscopic nodules, necrosis with microabscesses, and characteristic yeast or hyphal forms of Candida.136,137 The results of cultures of biopsy material are negative in most cases. PCR methodology has been used to diagnose hepatic candidiasis.138

Response rates to therapy with intravenous amphotericin B are better (almost 60%) for focal hepatic candidiasis than for disseminated disease. The success of treatment is currently far from optimal, however. Alternatives to amphotericin B are fluconazole; liposomal amphotericin; and intravenous echinocandins such as caspofungin, micafungin, or anidulafungin.139 The widespread use of prophylactic fluconazole in high-risk patients has resulted in lower rates of fatal visceral fungal infection while promoting a shift toward infections caused by other molds resistant to this agent.140

HISTOPLASMOSIS

Infection with Histoplasma capsulatum is acquired through the respiratory tract and in most cases is confined to the lungs. Severely immunocompromised persons (e.g., those with AIDS), however, are predisposed to disseminated histoplasmosis (see Chapter 33). The liver can be invaded in both acute and chronic progressive disseminated histoplasmosis. Fever, oropharyngeal ulcers, hepatomegaly, and splenomegaly may be present in patients with chronic disease.141 In children with acute hepatic disease, which appears to be an extension of primary pulmonary infection, marked hepatosplenomegaly is universal and is associated with high fever and lymphadenopathy. In one series of 111 cases of disseminated histoplasmosis, serum ALT levels were elevated in 39%, AST levels were elevated in 27%, and alkaline phosphatase levels were >200 U/L in 55%.142 Hepatosplenomegaly is present in approximately 30% of adults with acute disease (often the AIDS-defining illness).

Yeast forms can be identified in liver biopsy specimens with standard hematoxylin and eosin staining. The silver methenamine method is superior for detecting yeast forms in areas of caseating necrosis or in granulomas. The organism is difficult to culture and almost never grows from biopsy specimens. Serologic testing for complement-fixing antibodies is therefore helpful in confirming the diagnosis. In immunocompromised persons who may not be capable of mounting an antibody response, detection of H. capsulatum antigens in urine and serum can be useful.143 Treatment options include therapy with amphotericin B, fluconazole, or itraconazole.

LIVER ABSCESS

PYOGENIC

In the past, most cases of pyogenic liver abscess were a consequence of appendicitis complicated by pylephlebitis (portal vein inflammation) in a young patient. This presentation is less common today as a result of earlier diagnosis and effective antibiotic therapy. Most cases now are cryptogenic or occur in older men with underlying biliary tract disease.144 Predisposing conditions include malignancy, immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, and previous biliary surgery or interventional endoscopy.

Pathogenesis

Infections of the biliary tract (e.g., cholangitis, cholecystitis) are the most common identifiable source of liver abscess. Infection may spread to the liver from the bile duct, along a penetrating vessel, or from an adjacent septic focus (including pylephlebitis). Pyogenic liver abscess may arise as a late complication of endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile duct stones or within three to six weeks of a surgical biliary-intestinal anastomosis.144 Pyogenic liver abscesses may complicate recurrent pyogenic cholangitis, which is found predominantly in East and Southeast Asia and is characterized by recurring episodes of cholangitis, intrahepatic stone formation, and, in many cases, biliary parasitic infections (see Chapter 68). Less commonly, liver abscess is a complication of bacteremia arising from underlying abdominal disease, such as diverticulitis, appendicitis, perforated or penetrating peptic ulcer, gastrointestinal malignancy, inflammatory bowel disease, or peritonitis, or rarely from bacterial endocarditis or penetration of a foreign body through the wall of the colon. The risk of liver abscess may be increased in patients with underlying diabetes mellitus or cirrhosis.145,146 Occasionally, a pyogenic liver abscess may be the presentation of a hepatocellular or gallbladder carcinoma or a complication of chemoembolization or percutaneous ablation of a hepatic neoplasm.147

Microbiology

Most pyogenic liver abscesses are polymicrobial. The bacterial organisms that have been cultured from liver abscesses are listed in Table 82-3. The most frequently isolated organisms are Escherichia coli and Klebsiella, Proteus, Pseudomonas, and Streptococcus species, particularly the Streptococcus milleri group. Certain virulent strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae can cause liver abscess in the absence of underlying hepatobiliary disease, often with metastatic infection.148 With improved cultivation methods and earlier diagnosis, the number of cases caused by anaerobic organisms has increased. The most commonly identified anaerobic species are Bacteroides fragilis and Fusobacterium necrophorum; anaerobic streptococci also have been identified. Pyogenic abscess associated with recurrent pyogenic cholangitis may be caused by Salmonella typhi. Clostridium and Actinomyces species are uncommon causes of liver abscess, and rare cases are caused by Yersinia enterocolitica, Pasteurella multocida, Haemophilus parainfluenzae, and Listeria species. Septic melioidosis also has been described. Liver abscesses caused by Staphylococcus aureus infection are most common in children and patients with septicemia or other conditions associated with impaired host resistance, including chronic granulomatous disease.149 Fungal abscesses of the liver may occur in immunocompromised hosts, particularly those with a hematologic malignancy (see earlier).

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Laboratory findings include anemia, leukocytosis, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and abnormal liver biochemical test results, especially an elevated serum alkaline phosphatase level. Blood culture specimens will identify the causative organism in at least 50% of cases.150 Direct cultures of aspirated fluid are useful for identification of the organism and determination of antibiotic susceptibility and should be sent for both aerobic and anaerobic culture.151 Chest x-rays may show elevation of the right hemidiaphragm and atelectasis.

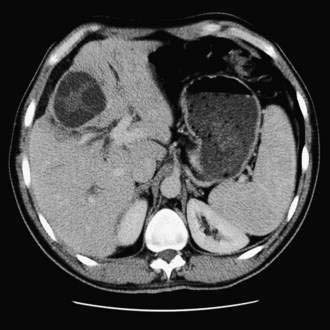

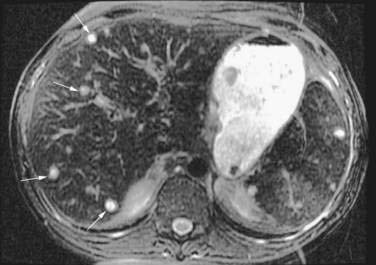

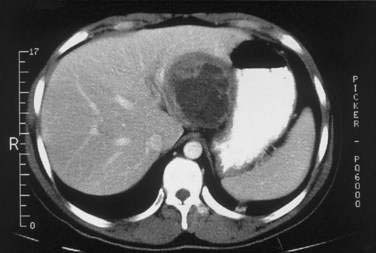

Ultrasonography and CT are the initial imaging modalities of choice. Abscesses as small as 1 cm in diameter can be detected. Ultrasonography is inexpensive and accurate and can guide needle aspiration of the abscess. Culture specimens of aspirated material yield positive results in 90% of cases (although the yield probably is lower if the patient has been receiving antibiotics). CT also is accurate, with a sensitivity rate approaching 100%, but is more expensive than ultrasonography. Hepatic abscesses are usually hypodense on a CT scan and may display a rim of contrast enhancement in less than 20% of cases (Fig. 82-9). CT permits precise localization of an abscess, assessment of its relationship to adjacent structures, and detection of gas in the abscess, which is associated with increased mortality. An abscess must be distinguished from other mass lesions in the liver, including cystic lesions, benign and malignant neoplasms, soft tissue tumors (neurofibroma, leiomyoma, and malignant fibrous histiocytoma), focal nodular hyperplasia, and hemangiomas (see Chapter 94), as well as inflammatory pseudotumors. Magnetic resonance imaging is more sensitive than CT for detecting small abscesses, which have low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images and enhance with gadolinium. ERCP is indicated in patients with imaging evidence of biliary stones or prominent cholestasis.152 Rarely, arteriography may be of value in distinguishing an abscess from a tumor.

Figure 82-9. Computed tomographic scan showing multiple pyogenic abscesses in the liver.

(Courtesy of Dr. Mukesh Harisinghani, Boston, Mass.)

Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver (also called plasma cell granuloma) is a rare, benign lesion characterized by proliferating fibrous tissue infiltrated by inflammatory cells. The cause is unknown. Affected persons (typically young men) often have a history of recent infection, but a causative infectious agent is rarely isolated from the lesion. Additional associated disorders include chronic inflammatory and autoimmune disorders, particularly ascending cholangitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis, as well as diabetes mellitus, Sjögren’s syndrome, gout, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, HIV infection, Epstein-Barr virus infection, and acute myeloblastic leukemia. Patients typically present with intermittent fever, abdominal discomfort, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, and malaise and have hepatomegaly, right upper quadrant tenderness, and jaundice on physical examination. Portal hypertension may develop. Laboratory findings also are similar to those associated with liver abscess, including polyclonal hyperglobulinemia in 50% of cases, and imaging studies generally are interpreted as showing a tumor or an abscess. Treatment generally has been by surgical resection of the lesion, although some patients may recover spontaneously or after treatment with antibiotics or glucocorticoids, once the diagnosis is made on the basis of needle biopsy findings.153,154

Prevention and Treatment

Pyogenic liver abscesses are best prevented by prompt treatment of acute biliary and abdominal infections and by adequate drainage of infected intra-abdominal collections under appropriate antibiotic coverage. Treatment of a hepatic abscess requires antibiotic therapy directed at the causative organism(s) and, in most cases, drainage of the abscess, usually percutaneously with radiologic guidance. An indwelling drainage catheter may be placed in the abscess until the cavity has resolved, particularly for lesions greater than 5 cm in size, although intermittent needle aspiration may be as effective as continuous catheter drainage for smaller lesions.155,156 With multiple abscesses, only the largest abscess may need to be aspirated; smaller lesions often resolve with antibiotic treatment alone, but rarely, each lesion may need drainage. For a small abscess, antibiotic therapy without drainage may suffice. Biliary decompression is essential when a hepatic abscess is associated with biliary tract obstruction or communication and may be accomplished through the endoscopic or transhepatic route (see Chapter 70). Surgical drainage of a hepatic abscess may be necessary in patients with incomplete percutaneous drainage, unresolved jaundice, renal impairment, a multiloculated abscess, or a ruptured abscess.157 A laparoscopic approach may be feasible in select cases.

Initial antibiotic coverage, pending culture results, should be broad in spectrum and include ampicillin and an aminoglycoside (when a biliary source is suspected) or a third-generation cephalosporin (when a colonic source is suspected), plus, in either case, metronidazole, to cover anaerobic organisms. If amebiasis is suspected, metronidazole should be started before aspiration is performed. Alternative regimens include combinations of a beta-lactam and beta-lactamase inhibitor active against enteric organisms, including anaerobes. After culture results and sensitivity profiles have been obtained, antibiotic therapy directed at the specific organism(s) should be administered intravenously for at least two weeks and then orally for up to six weeks.158 For streptococcal infections, the use of high-dose oral antibiotics for six months may be preferable.

The mortality rate for patients with hepatic abscesses treated with antibiotics and percutaneous drainage has improved since the 1980s.157,159 A worse prognosis is associated with a delay in diagnosis, multiple abscesses, multiple organisms cultured from blood, a fungal cause, shock, jaundice, hypoalbuminemia, a pleural effusion, an underlying biliary malignancy, multiorgan dysfunction, sepsis, or other associated medical diseases.157,160–164 Complications of pyogenic liver abscess include empyema, pleural or pericardial effusion, portal or splenic vein thrombosis, rupture into the pericardium, thoracic and abdominal fistula formation, and sepsis. Metastatic septic endophthalmitis occurs in as many as 10% of diabetic patients with a liver abscess caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae.148

AMEBIC

Amebiasis occurs in 10% of the world’s population and is most common in tropical and subtropical regions (see also Chapter 109).165,166 In the United States, it is a disease of young, often Hispanic adults. Endemic areas include Africa, Southeast Asia, Mexico, Venezuela, and Colombia. Amebic liver abscess is the most common extraintestinal manifestation of amebiasis. Compared with affected persons who reside in an endemic area, persons in whom an amebic liver abscess develops after travel to an endemic area are older and more likely to be male, have marked hepatomegaly, and have a large abscess or multiple abscesses. The occurrence of an amebic liver abscess in a person who has not traveled to or resided in an endemic area should raise the suspicion of underlying immunosuppression, particularly AIDS.167,168 Other persons at increased risk include inpatients in residential institutions and men who have sex with men. Host factors that contribute to the severity of disease include younger age, pregnancy, malnutrition, alcoholism, glucocorticoid use, and malignancy.

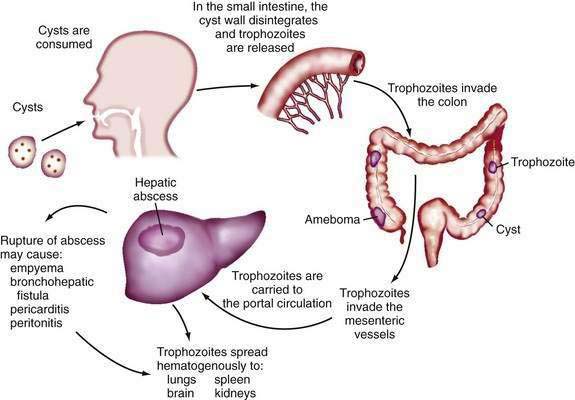

Pathogenesis

During its life cycle, Entamoeba histolytica exists as trophozoite or cyst forms (Fig. 82-10). After infection, amebic cysts pass through the gastrointestinal tract and become trophozoites in the colon, where they invade the mucosa and produce typical “flask-shaped” ulcers. The organism is carried by the portal vein circulation to the liver, where an abscess may develop. Occasionally, organisms travel beyond the liver and can establish abscesses in the lung or brain. Rupture of an amebic liver abscess into the pleural, pericardial, and peritoneal spaces can also occur.

Clinical Features

Amebic liver abscess is 10 times as common in men as in women and is rare in children.165 An amebic liver abscess is more likely than a pyogenic liver abscess to be associated with an acute presentation. Symptoms are present on average for two weeks by the time a diagnosis is made. A latency period between intestinal and subsequent liver infection of up to many years is possible, and less than 10% of patients report an antecedent history of bloody diarrhea with amebic dysentery.

Diagnosis