CHAPTER 21 Back Pain in Children and Adolescents

The prevalence of back pain in children and adolescents is increasing. Although it is assumed that pediatric back pain is rare, more recent studies have shown that more than 50% of children note episodes of back pain by 15 years of age.1–4 A survey of teenagers revealed that 39% complained of low back pain, but few presented for medical evaluation.5 Although the number of children and teens complaining of pain is increasing, children and adolescents who have a distinct diagnosis are decreasing in number. A study by Hensinger6 in 1985 found a specific diagnosis in 84% of children presenting for treatment of back pain. In a study 10 years later, a cause for back pain was identified in only 22% of 217 children evaluated with single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).7 The task of the evaluating surgeon is to identify which children are most likely to have an underlying musculoskeletal condition and require a comprehensive evaluation to identify the etiology of their pain.

History

The initial step in distinguishing which children require symptomatic treatment from children who warrant a complete radiographic evaluation is obtaining a detailed history. The characteristics of the pain are most helpful. Acute pain after trauma is seen with fractures, disc herniations, and apophyseal ring separations. Insidious pain without a clear-cut antecedent event is characteristic of developmental conditions, such as Scheuermann kyphosis, and benign neoplasms. Recurrent pain associated with athletics and relieved by rest leads to suspicion of overuse injuries such as spondylolysis. Unremitting pain, especially if it is worse at night or wakes the child from sleep, is most worrisome because it is seen in malignancies and infection.7,8

The patient’s age is very helpful in directing the evaluation of back pain. Back pain in children younger than 4 years is usually due to either infection or malignancy. A history of fever, limp, and malaise should be sought, and an immediate diagnostic evaluation should be performed. Children in the 1st decade of life commonly present with discitis and osteomyelitis, and malignant neoplasms, but they also may present with benign conditions such as eosinophilic granuloma.8 Patients older than 10 years are most likely to have back pain secondary to trauma or overuse, resulting in spondylolysis, disc herniations, or apophyseal fractures.9 Scheuermann kyphosis manifests in adolescence. Teens also rarely present with malignancies, so the physician should always remain cautious while weighing the relative frequency of conditions based on age.

A family history should be taken regarding back pain. Adolescents with ill-defined pain, no constitutional symptoms, no history of excessive athletic activity, no anatomically consistent neurologic complaints, and a positive family history often do not have a musculoskeletal etiology for their pain.2,8 Psychosomatic pain does occur in this age group, but remains a diagnosis of exclusion.

A complete review of systems should be obtained. Back pain associated with menses is rarely orthopaedic in nature. Flank pain may be renal in origin. A more recent study showed that 5% of children presenting to an emergency department for evaluation of back pain had urinary tract infections.10

Diagnostic Studies

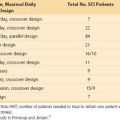

With the information obtained from the history and physical examination, a focused approach to diagnostic studies can be taken (Table 21–1). If the patient is 10 years of age or younger, if the duration of pain is 2 months or longer, if there is night pain, or if there are constitutional symptoms, standard radiographs of the spine should be obtained immediately. If the patient is older, the pain is of short duration, and the physical examination is completely normal, the patient may be observed for a short time. Most patients fall between these two groups, and the extent of the radiographic evaluation should be decided on an individual basis.

| X-ray | History of significant trauma; night pain, fever, or inability to walk; age ≤8 yr; duration of pain >2 mo |

| Bone scan | Negative plain x-rays with normal neurologic examination; persistent pain; history of athletic overuse |

| Computed tomography | Positive plain x-ray or bone scan |

| Magnetic resonance imaging | Abnormal neurologic examination; painful scoliosis in patient <8 yr old; painful left thoracic scoliosis |

| Laboratory tests | Night pain; fever; age <8 yr; constant pain |

Radiographs

Plain radiographs are the best screening examination for a child with back pain.7,11 Anteroposterior and lateral views of the spine should be obtained without pelvic shielding because the shield hides the sacrum, the sacroiliac joints, and the pelvis. The physician should carefully examine the films for alignment, disc space narrowing, endplate irregularities, and lytic or blastic lesions. Each pedicle should be identified on the anteroposterior view. If a question of a lesion arises, a focused coned-down view taken with the patient supine provides better bony detail.

The identification of scoliosis on screening films of a child with back pain should not lead to the conclusion that the curve is the cause of the pain. Although 33% of adolescents with the diagnosis of scoliosis complain of some back pain, it is usually located over the rib prominence and is rarely a presenting complaint.11 The apex of the curve should be carefully inspected for bony lesions in a child with painful scoliosis.

Bone Scan

SPECT combines the physiology of a bone scan with the ability to localize lesions precisely within the vertebra similar to a computed tomography (CT) scan. Increased uptake can be seen in the posterior elements in stress fractures, so SPECT is particularly helpful in diagnosing spondylolysis.12–15 A study of 100 patients 2 to 18 years old presenting with low back pain found that a negative SPECT scan was most helpful in ruling out an organic cause for back pain of less than 6 weeks’ duration.16

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI is used to image the neural axis in all children who have an abnormal neurologic examination. MRI can identify spinal neoplasms, cord abnormalities such as syringomyelia and tethers, discitis, and herniated discs. Auerbach and colleagues16 recommended MRI as the best imaging modality for patients with low back pain of greater than 6 weeks’ duration.

Differential Diagnosis

Table 21–2 summarizes differential diagnoses based on the child’s age.

| Age <5 yr | Tumor, discitis |

| Age 5-10 yr | Langerhans cell histiocytosis, discitis, tumor or leukemia |

| Age 10-18 yr | Scheuermann kyphosis, herniated disc or apophysis, spondylolysis, osteoid osteoma, tumor or leukemia |

Disc Herniation

Intervertebral disc herniation occasionally occurs in older children and teens. The onset of symptoms is usually related to acute or repetitive trauma.17 Back pain with radiation into the legs is a complaint in 82% of affected patients.18 Pain is exacerbated by activity and relieved by rest. As in adults, pain is worsened by sneezing, coughing, or straining.

Physical examination reveals decreased spinal flexibility, with inability to touch the toes. On bending toward the floor, the patient often lists to one side. The straight-leg raise test (Lasègue sign) is positive in 85% of children with herniated discs; objective neurologic findings, such as absent reflexes, motor weakness, and decreased sensation, are less common in children than in adults.19

Radiographs are generally normal, although if the child is sufficiently symptomatic, films may show an olisthetic scoliosis or trunk lean. There is an increased incidence of concomitant spinal abnormalities in patients with herniated discs. In particular, congenital spinal stenosis is frequently seen. Other findings include transitional vertebrae or spondylolisthesis.20

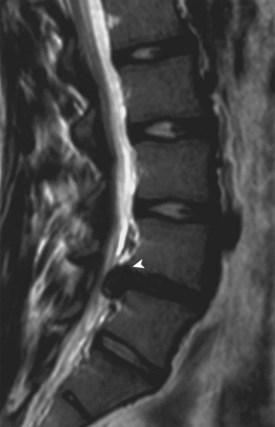

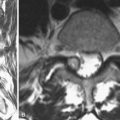

Disc herniation is seen best on MRI (Fig. 21–1). The involved disc is readily appreciated, and other processes that might produce sciatica, such as epidural abscess and spinal cord tumor, can be ruled out.8 Herniation of the disc can be differentiated from an avulsed vertebral apophysis on either MRI or CT scan. Correlation of MRI findings with the history and clinical examination is necessary because mild disc bulging can exist as a normal variant.

Treatment is initially conservative, consisting of anti-inflammatory medication and bed rest. Prolonged nonoperative management may lead to persistent pain, however, so if the patient does not respond to symptomatic treatment, disc excision should be performed.19 Short-term results are very encouraging, with 95% good and excellent results and nearly universal resolution of back and leg pain.19 Although long-term follow-up shows deterioration in results, with 24% reoperation after 30 years,21 outcome studies show that patients treated by discectomy as adolescents function better than adults after similar surgery.22 Surgical technique for adult and pediatric patients is similar. Some early reports indicate pediatric patients can safely undergo endoscopic percutaneous discectomy.23

Apophyseal Ring Fracture (Slipped Vertebral Apophysis)

The apophyseal ring fracture, also known as a slipped vertebral apophysis, occurs in adolescents and young adults. The etiology is either acute trauma resulting in rapid flexion and axial compression or cumulative microtrauma. The fracture typically develops at the junction of the posteroinferior vertebral body and the cartilaginous ring apophysis, with posterior displacement of the fragment into the spinal canal.24 CT scan can show the size and location of the bony fragment, with large central fragments being most common and most likely to result in significant pain if left untreated.25

The diagnosis is made radiographically. High-quality lateral radiographs may show an arc-shaped rim of cartilage, cartilage with attached underlying bone, or a small triangular bony fragment lying posterior to the vertebral body. The fragment is best visualized on CT scan.24 The levels most frequently injured are L4 or S1. Treatment is surgical removal of the avulsed fragment.

Developmental Disorders

Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolysis refers to a stress fracture of the pars interarticularis, occurring predominantly in the lower lumbar spine. The most frequent level is L5, followed by L4. It is extremely rare to have more than one vertebral level involved. Spondylolysis is bilateral in 80% of cases and unilateral in 20%. More recent studies show that 50% of young athletes presenting for evaluation of back pain have injuries to the pars interarticularis.26 The mechanism of injury is repetitive microtrauma in hyperextension, overloading the pars interarticularis, over time leading to stress fracture. Sports linked to a high incidence of spondylolysis are gymnastics, diving, ballet, and football. Gymnasts and football linemen have a fourfold increase in incidence of spondylolysis compared with the general pediatric population.27

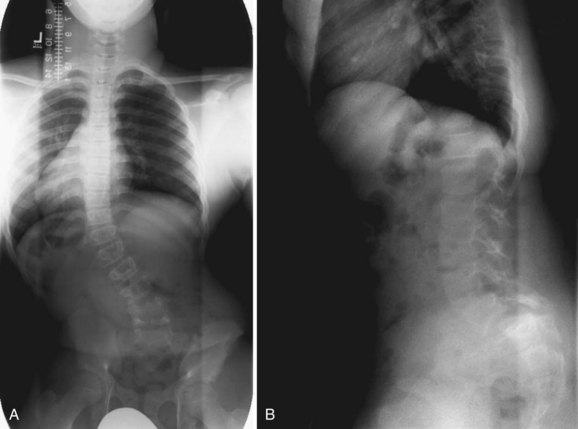

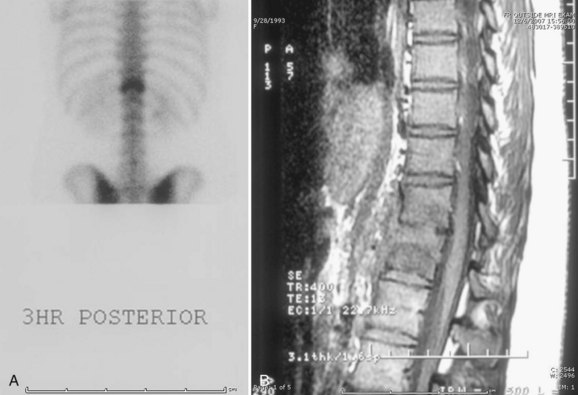

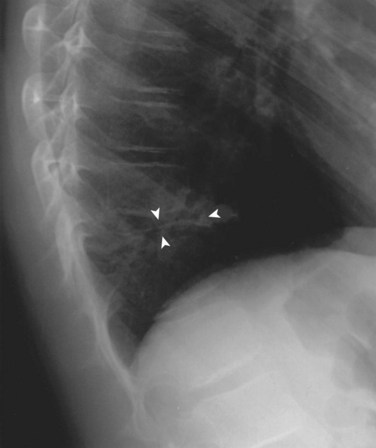

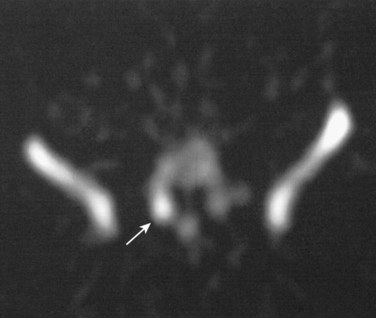

Lateral radiographs may show lysis across the pars interarticularis, and oblique radiographs can be helpful in less obvious cases (Fig. 21–2). The appearance of a collar on the “Scottie dog” suggests stress fracture. Often, plain radiographs are nondiagnostic. In these cases, scintigraphy can reveal increased tracer uptake at the involved level. The use of SPECT is particularly helpful in localizing increased uptake in the pars interarticularis (Fig. 21–3).13,14,28 A specific scintigraphic pattern, seen as a triangle of increased signal with increased uptake in the pedicles, has been described.29 Positive bone scans and SPECT imaging are generally seen in the prefracture state and in relatively acute injuries.30 The bone scan may not be “hot” in chronic spondylolysis.14

FIGURE 21–2 Lateral radiograph of lumbar spine shows spondylolysis of L5 in a 16-year-old volleyball player.

FIGURE 21–3 Increased uptake in pars interarticularis of an adolescent ballerina with spondylolysis.

MRI has also been used to diagnose spondylolysis, but false-positive scans can occur.31 Better bony definition of the fracture is obtained using CT scans. Additionally, CT is superior to MRI in the assessment of incomplete fractures and in establishing healing in patients with spondylolysis.32 The pars is imaged by using a reverse gantry angle and obtaining thin slices on the CT scan.33

Treatment of spondylolysis is initially nonoperative and primarily involves modifying the patient’s level of athletic activity.34 Cessation of sport until the resolution of symptoms is combined with a concomitant exercise program to stretch the hamstrings and strengthen the paraspinal and abdominal musculature. Resumption of activities is gradual. The patient’s technique or training should be modified to minimize recurrent fractures. Use of a antilordotic lumbar orthosis increases the success of nonoperative treatment, particularly in patients with acute injuries and “hot” bone scans.35,36 A more recent study found resolution of symptoms after bracing correlated with initial increased activity on SPECT scans and with decreased uptake on follow-up scans, whereas SPECT scans for patients whose pain did not improve showed no significant decrease in activity after bracing.37

The overall success rate of nonoperative treatment ranges from 73% to 100%.36 A multicenter study of 436 children and adolescents with CT-proven spondylolysis found 95% excellent results and 100% return to sport without surgery after 3 months of cessation of activity with use of a thoracolumbar orthosis.38 Patients who have normal radiographs but are found to have a stress reaction without fracture on further imaging are highly likely to improve (and not progress to radiographic fracture) with conservative treatment.39,40 Surgery is typically reserved for the few patients whose symptoms are refractory to 6 months of conservative measures and whose pain recurs with activity after initial nonoperative success.41

Spondylolisthesis is a related condition in which anterior slippage of a vertebral body occurs on the more distal vertebra. Most often, it is due to bilateral spondylolysis, with the portion of the vertebra anterior to the pars fracture slipping anteriorly. Dysplastic spondylolisthesis occurs in teens who have an elongated but intact pars interarticularis, which allows for the anterior translation without pars fracture.42

Patients with spondylolisthesis often present with complaints of low back pain. The pain may radiate into the legs. Physical findings mimic findings of spondylolysis, with the addition of a possible palpable step-off at the area of listhesis. In severe spondylolisthesis, the buttocks may appear “heart-shaped.” If there is significant hamstring tightness, gait alterations are seen: The teen appears to be shuffling with posterior pelvic tilt. Patients may have a painful, or olisthetic, scoliosis (Fig. 21–4).

Treatment is initially conservative in mild spondylolisthesis and surgical as the magnitude of the slip increases. Surgical treatment of high-grade spondylolisthesis is recommended, but preferred techniques vary among surgeons, and reduction remains controversial.43 The surgical treatment of spondylolisthesis and spondylolysis is discussed in further detail in Chapter 27.

Scheuermann Kyphosis

The diagnosis is made radiographically (Fig. 21–5). Criteria for the diagnosis of Scheuermann disease have been outlined by Sorenson as (1) three contiguous vertebral bodies with greater than 5 degrees of anterior wedging; (2) abnormal disc narrowing; (3) endplate irregularities; and (4) Schmorl nodes, defined as disc herniations into the vertebral bodies.

Most patients with Scheuermann disease can be managed nonoperatively.44 Physical therapy exercises and nonsteroidal medication can be helpful in relieving symptoms. The role of bracing is controversial. Patients with significant remaining spinal growth may benefit from orthotic treatment; it has been proposed that correction of deformity may be achieved in compliant patients.45 The Milwaukee brace is the orthosis of choice for the treatment of Scheuermann disease.46 Surgical correction of deformity and fusion is reserved for patients with severe kyphosis measuring greater than 75 degrees, patients whose symptoms are refractory to conservative measures, and patients who have significant cosmetic concerns.47 The management of Scheuermann kyphosis is discussed in Chapter 26.

Lumbar Scheuermann Disease

Lumbar Scheuermann disease is a less common variant in which increased kyphosis and endplate changes are seen in the lumbar spine.48 It also occurs most frequently in adolescence, and its cause is believed to be overuse. Microfractures occur in the vertebral endplates resulting in low back pain. Radiographs reveal endplate irregularities and disc space narrowing, anterior Schmorl nodes, and possible anterior wedging of the affected vertebrae leading to loss of lumbar lordosis. Radiographs may also show associated spondylolysis or scoliosis.15,49 The radiographic appearance of vertebral changes and disc space narrowing may resemble infection or tumor. Scintigraphy may reveal mildly increased uptake at one or two vertebral levels.15 MRI shows signal change and dehydration in the lumbar discs, with further disc deterioration occurring over time.50 Treatment is symptomatic, and pain is usually ameliorated with modification of activity or use of an orthosis.

Idiopathic Scoliosis

Most patients who have idiopathic scoliosis do not complain of back pain, but symptoms are not as uncommon as previously thought. In a study by Ramirez and colleagues,11 32% of 2442 children who were thought to have idiopathic curves complained of some degree of back pain. Left-sided thoracic curves, which were associated with spinal cord abnormalities, were the most common factor associated with a positive diagnosis on further evaluation. Plain radiographs were found to be sufficient in the evaluation of typical curves if the neurologic examination was normal. Careful inspection of the apex of the deformity and at the lumbosacral junction (for spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis) occasionally yields a cause for the pain and the scoliosis (see Fig. 21–4). In the absence of neurologic findings on physical examination, MRI was not helpful. A more recent study showed that MRI was useful in identifying neural axis abnormalities in 6% of 104 patients. Back pain and early age of onset of scoliosis were present in patients with MRI abnormalities.51

Syringomyelia

Syringomyelia is defined as cystic dilation of the central canal of the spinal cord. The dilation of the cord leads to abnormalities in the neurologic pathways that transmit pain and temperature. Although not always symptomatic, patients may complain of pain. There is a predisposition toward left thoracic scoliosis in patients with syringomyelia.52 Physical findings include scoliosis, foot deformities such as cavus, decreased sensation, and asymmetrical abdominal reflexes. The syrinx is clearly imaged on MRI. Treatment is neurosurgical decompression, although controversy exists regarding the size of syrinx that requires surgery.

Idiopathic Juvenile Osteoporosis

Idiopathic juvenile osteoporosis is a rare disease that usually affects children in the first 2 decades of life. Presenting symptoms include back and leg pain owing to compression fractures and pain during weight bearing.53,54 Radiographic findings include vertebral wedging owing to compression fractures with mildly increased kyphosis. Bone mineral density is decreased, but metabolic laboratory values are normal. The differential diagnosis includes leukemia. Orthotic management of back pain is usually sufficient. Medical management should be under the supervision of a pediatric rheumatologist. The disease is self-limiting, and symptoms resolve during puberty.55

Infectious and Inflammatory Etiologies

Discitis

Discitis is defined as a presumed bacterial infection of the intervertebral disc space. It is the most common cause of back pain in young children. The incidence of discitis is greatest in children 5 years old and younger, although it can occur in older children.56 The etiology is believed to be infectious. In an immature child, blood vessels traverse the vertebral endplates and terminate in the nucleus pulposus. In young children, the disc is vascular, and this allows for seeding of bacteria into the disc space.57–59 Presenting complaints vary but include back pain, refusal to walk, limping, and abdominal pain. The child usually is systemically ill, and patients often present to the emergency department. Approximately half have fever on presentation.

Physical examination reveals spinal stiffness, and often the spine is held in a flexed position. If asked to retrieve a toy from the floor, a child with discitis squats by bending the knees rather than bend the spine. Young children may exhibit Gowers sign when rising from the floor, using their upper extremities to push up on the legs as a strategy to minimize lumbar motion.60 Tenderness to palpation of the affected area may be present.

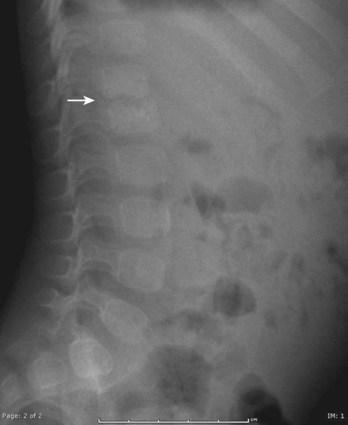

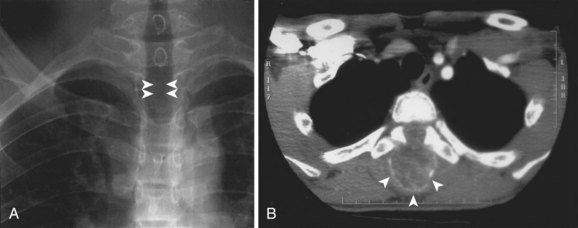

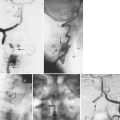

Radiographic findings are usually minimal at the time of presentation. Subtle disc space narrowing and paraspinal soft tissue swelling on the lateral view are the first radiographic changes (Fig. 21–6). Over time, endplate irregularities are seen. Because plain radiographs are usually normal at the time of presentation, further imaging is required. Technetium bone scans show increased uptake on both sides of the affected disc space (Fig. 21–7A). Bone scans are positive in 74% to 100% of children with discitis61,62; they lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment. MRI also localizes the infection and delineates the extent of soft tissue involvement (Fig. 21–7B). In patients who are refractory to treatment, MRI is useful in assessing whether or not a soft tissue abscess is present.63 MRI shows decreased signal on T1-weighted images and increased signal on T2-weighted images. If an abscess is present, there is peripheral enhancement with the administration of gadolinium.64

The evaluation of a child with possible discitis also includes obtaining laboratory studies. Elevations of erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein are seen in greater than 90% of children with discitis.8 The white blood cell count may be elevated, but is less reliable.57 Blood cultures should be obtained and are positive in greater than 50% of children with discitis.62

In the past, the treatment of discitis was controversial, but now there is more agreement that discitis represents a bacterial infection and should be treated with antibiotics.57,63,65 Cultures of the intervertebral disc are positive in 60% of children, with Staphylococcus aureus the most common organism. A more recent study of disc space cultures showed S. aureus was cultured in 55% and Kingella kingae was cultured in 27% of children with discitis.66 Because of the preponderance of S. aureus and the fact that 40% of cultures from the disc space remain negative, routine aspiration of the affected disc is not recommended.65 If the patient fails to improve quickly with antistaphylococcal antibiotics, fine-needle aspiration under CT guidance can be useful.67 Although administration of a second-generation cephalosporin for 3 weeks has been recommended,65 epidemiologic trends in antibiotic resistance may alter which antibiotic should be chosen. Surgical biopsy and débridement are reserved for patients who fail medical management, have a neurologic deficit, have an abscess on MRI, or whose diagnosis is in question.

The outcome of pediatric discitis is favorable. Ten-year radiographic follow-up has shown narrowed disc space (60% of children) or bony ankylosis (40%), but kyphosis is rare and generally mild, and patients are pain-free.68

Disc space infection in infants younger than 1 year of age is usually very aggressive and requires immediate diagnosis and treatment. Infants are often septic at presentation. Residual kyphosis after eradication of the infection has been described.69

Vertebral Osteomyelitis

The distinction between discitis and osteomyelitis in children is blurred. It is believed that osteomyelitis is a continuation of discitis,58 with the two entities representing a condition termed infectious spondylitis. Osteomyelitis produces more notable vertebral body radiographic changes. S. aureus is the most common organism.59

Opportunistic infections may also affect the vertebral column, especially in immunocompromised patients, such as patients with malignancies or who have had organ transplants. Fungal infections such as coccidioidomycosis are rare, but must be kept in mind in endemic regions.70

Tuberculosis is increasing in frequency and is seen most commonly in children from endemic regions. Symptoms include fever, malaise, weight loss, and night sweats. Neurologic findings occur more frequently in tuberculosis than in discitis.71 Radiographic changes are more advanced in children with tuberculous spondylitis and consist of bony destruction of the vertebral body, kyphosis, soft tissue abscesses, and soft tissue calcifications. CT findings include erosions with calcification and intraspinous, paravertebral, and epidural abscesses.72,73 Chest radiograph shows evidence of tuberculosis in 67% of children with tuberculous infection of the spine.72 The purified protein derivative test is usually positive except in children with immunologic challenge, in whom it remains nonreactive. Pathologic examination of tissue from fine-needle aspiration of the affected bone yields a positive diagnosis in 83% of children and teens74 and shows epithelioid giant cells and caseous necrosis or tubercle bacilli. Polymerase chain reaction has been used for faster identification of the organism.

Ankylosing Spondylitis and Rheumatologic Conditions

Ankylosing spondylitis is a rheumatologic condition characterized by loss of spinal mobility. It may manifest in adolescents as back pain. It occurs more frequently in boys than in girls. Physical findings include loss of lumbar flexibility so that lordosis does not reverse on forward flexion, increased kyphosis, and limited chest expansion with inspiration. Plain radiographs may reveal sclerosis, narrowing, or fusion of the sacroiliac joints. MRI has been shown to be superior to bone scan in identifying inflammation of the sacroiliac joint.75,76 Laboratory evaluation of patients with ankylosing spondylitis shows a high incidence of HLA-B27. Onset of ankylosing spondylitis before the age of 16 years has been linked to worse functional outcomes than in patients with onset in adulthood.77 Other rheumatologic conditions linked with back pain include polymyositis, dermatomyositis, and inflammatory bowel disease.

Hematologic Conditions

Sickle Cell Anemia and β-Thalassemia

In a study of pediatric patients presenting to a Canadian emergency department for the evaluation of back pain, 13% were found to have sickle cell anemia.10 The spine has been reported as the second most common site for pain crisis in these patients, second only to the knee. Anemia is present in 86%.78 Physical examination reveals tenderness to palpation. Treatment is pain management and admission to the hematology service.

β-thalassemia may also produce pain crises that affect the spine. In a more recent study, 25% of patients with thalassemia complained of low back pain.79

Neoplasms

Aneurysmal Bone Cysts

Aneurysmal bone cysts are nonmalignant expansile lytic lesions of bone that are characterized by their vascularity. Although not malignant tumors, they can be locally aggressive. Their etiology is unclear; a few familial cases have been identified.80 Approximately 15% of aneurysmal bone cysts affect the spinal column, with a predilection for the posterior elements. If of sufficient size, the lesion may extend into the anterior column.81,82 A large multicenter series of spinal aneurysmal bone cysts documented 30% were located in the cervical spine, 30% were in the thoracic spine, and 40% were in the lumbar spine.83

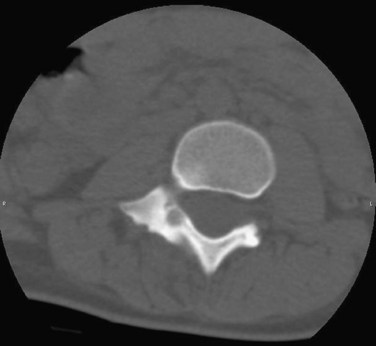

Radiographs show an expansile lytic lesion with a “bubbly” appearance. There is expansion of the cortex. CT scans best define the extent of the lesion and reveal the thin rim of surrounding bone (Fig. 21–8). Sacral lesions have been occasionally shown to affect more than one vertebral level.84

Treatment of aneurysmal bone cysts is surgical curettage with bone grafting.85 Because of the vascularity of the cysts, preoperative embolization is very helpful in reducing intraoperative blood loss and improving visualization.86–88 Spinal cord monitoring during embolization has been advocated to avoid vascular injury to the spinal cord.89 Scheduling the surgical resection shortly after embolization is necessary to prevent revascularization of the lesion before curettage. When resection of the lesion leads to mechanical instability, simultaneous fusion is recommended.90 There is a 10% to 14% recurrence rate after curettage and grafting for spinal aneurysmal bone cysts. A four-step surgical program, consisting of curettage, use of a high-speed bur, electrocautery, and bone grafting, with stabilization via short posterior fusion with instrumentation as needed, has been proposed more recently, with all patients disease-free at follow-up.91

In limited cases, repeat embolizations and radionuclide ablation have been used to treat spinal aneurysmal bone cysts definitively.88 Repeat embolization has been advocated in patients who do not have neurologic findings or pathologic fracture, in patients in whom the diagnosis is certain, and in patients whose lesions have recurred.92

Osteoid Osteoma

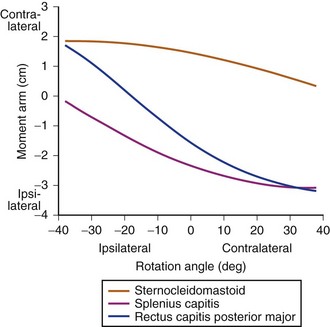

Physical examination reveals decreased spinal flexibility. Often patient stands with a list. The neurologic examination is generally normal. Plain radiographs are usually insufficient to make the diagnosis, but an olisthetic scoliosis might be apparent. When scoliosis is present, the lesion is usually located in the concavity of the apex of the curve.93 Bone scan is positive, with distinct increased uptake seen (Fig. 21–9). CT scans provide the best imaging of osteoid osteomas, with a small radiolucent nidus and surrounding sclerosis and new bone apparent (Fig. 21–10). MRI shows increased signal intensity in the muscles and surrounding bone.94 The MRI appearance and the tendency for enhancement in the soft tissues near the lesion may lead the physician to suspect a malignant tumor.95

FIGURE 21–9 Bone scan of a 15-year-old boy with a 2-year history of back pain shows increased uptake at T10.

Long-term administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication can provide pain relief in a small group of patients with spinal osteoid osteomas, so a trial of nonsurgical treatment is warranted. Usually, symptoms are sufficient to warrant surgical removal of the nidus, which typically results in immediate pain relief. Intraoperative CT has been used to target the nidus better and minimize bony resection.96 Newer treatments are under investigation, including percutaneous CT-guided drilling of the nidus with a bur and thermocoagulation.97,98 When scoliosis has been long-standing, persistence of the deformity is possible after successful removal of the osteoid osteoma.

Osteoblastoma

Although osteoblastoma is a less common benign lesion of the spine, 40% of osteoblastomas are located in the vertebrae. They also are located in the posterior elements of the spine, but because they are by definition larger than osteoid osteomas, they often extend anteriorly into the vertebral bodies.99 The primary symptom of osteoblastoma is back pain, which is usually less severe than in osteoid osteoma. Neurologic abnormalities may result from the size of the lesion and its encroachment on the spinal canal or neural foramina.94

The lesion can be usually seen on plain radiographs, but CT scans are invaluable in assessing the size and extent of osteoblastoma. As in osteoid osteoma, MRI in osteoblastoma can overestimate the extent and aggressiveness of the lesion.100 Plain radiographs also reveal scoliosis in approximately 40% of affected patients.93

Eosinophilic Granuloma (Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis)

Eosinophilic granuloma, also known as Langerhans cell histiocytosis or histiocytosis X, is a peculiar condition of childhood typified by the development of lytic lesions of bone. The lesions may occur singly or affect multiple areas of the skeleton, including the spine. When the condition is associated with systemic involvement, it is known as Hand-Schüller-Christian disease or the more severe Letterer-Siwe disease. Eosinophilic granuloma has a higher incidence in boys. The average age at diagnosis is 6 years, with most patients in the 1st decade of life.101

Radiographs show lytic lesions within the vertebral body or, more rarely, the posterior elements. Larger lesions lead to collapse of the vertebral body, which can be symmetrical or asymmetrical (Fig. 21–11). Although vertebra plana (also known as “coin-on-end” appearance) is the classically described spinal lesion in eosinophilic granuloma, only 40% of children with eosinophilic granuloma and vertebral lesions have been reported to have vertebra plana.102 Skeletal surveys often identify other sites of involvement, which supports the diagnosis. Typical sites of involvement include the skull, the pelvis, and the diaphyses of the long bones. Bone scan is positive in 90% of children with eosinophilic granuloma.103

The differential diagnosis includes leukemia, infection, and other malignant tumors such as Ewing sarcoma.104 If the radiographic appearance is atypical and other peripheral skeletal lesions are not identified, a surgical biopsy of the spinal lesion is warranted. Pathologic specimens show clonal proliferation of Langerhans-type histiocytes, eosinophils, and giant cells.105

Most patients with eosinophilic granuloma experience spontaneous resolution of disease. Because the condition seems to be self-limiting, the indications for treatment are few. Back pain resulting from a unifocal spinal lesion can usually be relieved by rest and the use of orthoses.101,105 Patients with neurologic compromise may be treated with low-dose radiation therapy or with surgical débridement of the lesion and stabilization.103,106 Radiation therapy has fallen out of favor as treatment for eosinophilic granuloma of the spine because of the potential for secondary malignancies. Multifocal disease, particularly when associated with systemic involvement, is treated with chemotherapy.107

The long-term outcome of eosinophilic granuloma in the absence of systemic disease is very good. Recurrence of disease is not seen in children.107,108 Over time, improvement in vertebral body height is seen, although complete restoration to normal is unusual.109,110

Malignant Tumors

Leukemia

Leukemia is the most common pediatric malignancy that produces back pain. Many children first present to the orthopaedic surgeon; 6% to 25% of children with acute leukemia have been reported to present initially with back pain.111,112 Most of these children are initially misdiagnosed, so the orthopaedic surgeon must have a high level of suspicion to evaluate these patients properly.113 The history may reveal symptoms of pallor, fatigue, loss of appetite, or fever. The parent should be questioned about a history of bruising or abnormal bleeding.

Radiographic findings are not always initially present but include generalized osteopenia, vertebral compression fractures, and metaphyseal leukemic lines. Vertebral compression fractures occur in 7% of children with acute lymphocytic leukemia (Fig. 21–12).112,114

FIGURE 21–12 Osteopenia and multiple compression fractures in a child presenting with back pain owing to leukemia.

The diagnosis can usually be made on laboratory examination, with abnormalities seen in any or all of the three cell lines—anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate is usually elevated. Of children with leukemia, 10% or more initially have normal automated counts.114,115 Inspection of the peripheral smear reveals the diagnosis in some of these children.

Vertebral Malignant Tumors

Malignant tumors of the spine cause significant back pain in more than 50% of children at the time of diagnosis.116 Although rare, these tumors must remain in the differential diagnosis of pediatric back pain. Pain may radiate into the legs, resembling the symptoms of a herniated disc. Patients with disc herniation are in the 2nd decade of life, whereas children with spinal or spinal cord tumors may be younger. Neurologic deficits and reflex changes are uncommon in disc herniation but frequent in tumors.117

Vertebral tumors include Ewing sarcoma and osteosarcoma.118 Osteosarcoma rarely affects the spine.119 Radiographs are variable, with osteolytic, osteoblastic, and mixed appearances possible. CT and MRI are used to stage the tumor. Treatment is difficult.

Of Ewing sarcomas, 10% occur in the spine, with the sacrum the most frequent site.120 The average age at presentation is 13.3 years.121 Relentless back pain is the primary symptom. Neurologic deficits are present in 58% of patients with spinal Ewing tumors.122 Radiographs may show an expansile lytic lesion with variable vertebral collapse. Cases of Ewing sarcoma that radiographically resemble vertebra plana have been reported, leading to the misdiagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma.122 MRI delineates the extent of the lesion and its accompanying soft tissue mass.

Spinal Metastasis

Neuroblastoma is the most frequent tumor to metastasize to the spine in children.123 In a more recent study of 29 malignant spine tumors, neuroblastoma represented one third of all cases.116 Radiographs usually show diffuse vertebral involvement. The thoracic spine is most frequently involved. An elevation of urinary normetanephrine may help in establishing the diagnosis.120 Other tumors that involve the spine include rhabdomyosarcoma, Wilms tumor, and primary neuroectodermal tumors.124

Spinal Cord Tumors

Common spinal cord tumors in children are astrocytomas and ependymomas. The onset of symptoms is indolent. Neurologic signs, such as deterioration of gait, delay in motor skills, and loss of bladder control, raise suspicion.125–127 Back pain is usually present, leading to initial referral to the orthopaedic surgeon in 31% to 58% of patients who are eventually diagnosed with spinal cord tumors.125,126 Physical examination reveals motor deficits, clonus, and possibly scoliosis. There may be limitation of spinal flexibility. Radiographs can show changes secondary to pressure or expansion of the tumor, including absence or thinning of the pedicle or widening of the intervertebral foramina. Spinal cord tumors are best seen on MRI.

Psychosomatic Pain (Conversion Reaction)

As discussed in the beginning of this chapter, there are children in whom an organic etiology for back pain cannot be found despite thorough evaluation. Back pain can be influenced by psychosocial factors that alter the patient’s perception of pain and the effect of pain on everyday life. Psychosomatic pain remains a diagnosis of exclusion. It is more prevalent in adolescents, particularly in teens whose family members have a history of similar back pain. A detailed social history often reveals problems at home or school, often resulting in anxiety and depression. Treatment is difficult but includes intervention by psychologists and physical therapists. More recent studies show that 71% of children and adolescents who have negative diagnostic evaluations for back pain continue to have pain at an average follow-up of 4.4 years.7 Even 8 years after initial evaluation, 62% of 58 patients were still symptomatic.128

1 Feldman DS, Hedden DM, Wright JG. The use of bone scan to investigate back pain in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:790-795.

2 Selbst SM, Lavelle JM, Soyupak SK, et al. Back pain in children who present to the emergency department. Clin Pediatr. 1999;38:401-406.

3 Anderson K, Sarwark JF, Conway JJ, et al. Quantitative assessment with SPECT imaging of stress injuries of the pars interarticularis and response to bracing. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:28-33.

4 Early SD, Kay RM, Tolo VT. Childhood diskitis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11:413-420.

5 Kayser R, Mahlfeld K, Nebelung W, et al. Vertebral collapse and normal peripheral blood cell count at the onset of acute lymphatic leukemia in childhood. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2000;9:55-57.

6 Dormans JP, Moroz L. Infection and tumors of the spine in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(Suppl):79-97.

1 Burton AK, Clarke RD, McClune TD, et al. The natural history of low back pain in adolescents. Spine. 1996;21:2323-2328.

2 Balague F, Skovron ML, Nordin M, et al. Low back pain in schoolchildren: A study of familial and psychological factors. Spine. 1995;20:1265-1270.

3 Harreby M, Nygaard B, Jessen T, et al. Risk factors for low back pain in a cohort of 1389 Danish school children: An epidemiologic study. Eur Spine J. 1999;8:444-450.

4 Olsen TL, Anderson RL, Dearwater SR, et al. The epidemiology of low back pain in an adolescent population. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:606-608.

5 Wedderkopp N, Leboeuf-Yde C, Andersen LB, et al. Back pain reporting pattern in a Danish population-based sample of children and adolescents. Spine. 2001;26:1879-1883.

6 Hensinger RN. Back pain in children. In: Bradford DS, Hensinger RN, editors. The Pediatric Spine. New York: Thieme; 1985:41.

7 Feldman DS, Hedden DM, Wright JG. The use of bone scan to investigate back pain in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:790-795.

8 Ginsburg GM, Bassett GS. Back pain in children and adolescents: Evaluation and differential diagnosis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1997;5:67.

9 Micheli LJ, Wood R. Back pain in young athletes: Significant differences from adults in causes and patterns. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:15-18.

10 Selbst SM, Lavelle JM, Soyupak SK, et al. Back pain in children who present to the emergency department. Clin Pediatr. 1999;38:401-406.

11 Ramirez N, Johnston CEII, Browne RH. The prevalence of back pain in children who have idiopathic scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:364-368.

12 Bellah RD, Summerville DA, Treves ST, et al. Low back pain in adolescent athletes: Detection of stress injury to the pars interarticularis with SPECT. Radiology. 1991;180:509-512.

13 Bodner RJ, Heyman S, Drummond DS, et al. The use of single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) in the diagnosis of low-back pain in young patients. Spine. 1988;13:1155-1160.

14 Lusins JO, Elting JJ, Cicoria AD, et al. SPECT evaluation of lumbar spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. Spine. 1994;19:608-612.

15 Mandell GA, Morales RW, Harcke HT, et al. Bone scintigraphy in patients with atypical lumbar Scheuermann disease. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13:622-627.

16 Auerbach JD, Ahn J, Zgonis MH, et al. Streamlining the evaluation of low back pain in children. Clin Orthop. 2008;466:1971-1977.

17 Grobler LJ, Simmons EH, Barrington TW. Intervertebral disc herniation in the adolescent. Spine. 1979;4:267-278.

18 Parisini P, DiSilvestre M, Greggi T, et al. Lumbar disc excision in children and adolescents. Spine. 2001;26:1997-2000.

19 DeLuca PF, Mason DE, Weiand R, et al. Excision of herniated nucleus pulposus in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 1994;14:318-322.

20 Epstein JA, Epstein NE, Marc J, et al. Lumbar intervertebral disc herniation in teenage children: Recognition and management of associated anomalies. Spine. 1984;9:427-432.

21 Luukkonen M, Partanen K, Vapalahti M. Lumbar disc herniations in children: A long-term clinical and magnetic resonance imaging follow-up study. Br J Neurosurg. 1997;11:280-285.

22 Durham SR, Sun PP, Sutton LN. Surgically treated lumbar disc disease in the pediatric population: An outcome study. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:1-6.

23 Mayer HM, Mellerowicz H, Dihlmann SW. Endoscopic discectomy in pediatric and juvenile lumbar disc herniations. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1996;5:39-43.

24 Takata K, Inoue S, Takahashi K, et al. Fracture of the posterior margin of a lumbar vertebral body. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70:589-594.

25 Chang CH, Lee ZL, Chen WJ, et al. Clinical significance of ring apophysis fracture in adolescent lumbar disc herniation. Spine. 2008;33:1750-1754.

26 Sassmannhausen G, Smith BG. Back pain in the young athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2002;21:121-132.

27 Jackson DW, Wiltse LL, Cirinciane RJ. Spondylolysis in the female gymnast. Clin Orthop. 1976;117:68-73.

28 Lawrence JP, Greene HS, Grauer JN. Back pain in athletes. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14:726-735.

29 Van der Wall H, Storey G, Magnussen J, et al. Distinguishing scintigraphic features of spondylolysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22:308-311.

30 Dutton JA, Hughes SP, Peters AM. SPECT in the management of patients with back pain and spondylolysis. Clin Nucl Med. 2000;25:93-96.

31 Yamane T, Yoshida T, Mimatsu K. Early diagnosis of lumbar spondylolysis by MRI. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:764-768.

32 Campbell RS, Grainger AJ, Hide IG, et al. Juvenile spondylolysis: A comparative analysis of CT, SPECT, and MRI. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34:63-67.

33 Harvey CJ, Richenberg JL, Saifuddin A, et al. The radiological investigation of lumbar spondylolysis. Clin Radiol. 1998;53:723-728.

34 Smith JA, Hu SS. Management of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in the pediatric and adolescent population. Orthop Clin North Am. 1999;30:487-499.

35 D’Hemecourt PA, Zurakowski D, Driemler S, et al. Spondylolysis: Returning the athlete to sport participation with brace treatment. Orthopedics. 2002;25:653-657.

36 Morita T, Ikata T, Katoh S, et al. Lumbar spondylolysis in children and adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:620-625.

37 Anderson K, Sarwark JF, Conway JJ, et al. Quantitative assessment with SPECT imaging of stress injuries of the pars interarticularis and response to bracing. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:28-33.

38 Kurd MF, Patel D, Norton R, et al. Nonoperative treatment of symptomatic spondylolysis. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20:560-564.

39 Sys J, Michielsen J, Bracke P, et al. Nonoperative treatment of active spondylolysis in elite athletes with normal x-ray findings: Literature review and results of conservative treatment. Eur Spine J. 2001;10:498-504.

40 Takemitsu M, El Rassi G, Woratanarat P, et al. Low back pain in pediatric athletes with unilateral tracer uptake at the pars interarticularis on single photon emission computed tomography. Spine. 2006;31:909-914.

41 Cavalier M, Herman MJ, Cheung EV, et al. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in children and adolescents: I. Diagnosis, natural history, and nonsurgical management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14:417-424.

42 Lonstein JE. Spondylolisthesis in children: Cause, natural history, and management. Spine. 1999;24:2640-2648.

43 Cheung EV, Herman MJ, Cavalier R, et al. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in children and adolescents: II. Surgical management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14:488-498.

44 Tribus CB. Scheuermann’s kyphosis in adolescents and adults: Diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6:36-43.

45 Pizzutillo PD. Nonsurgical treatment of kyphosis. Instr Course Lect. 2004;53:485-491.

46 Sachs B, Bradford D, Winter R, et al. Scheuermann kyphosis: Follow-up of Milwaukee brace treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69:50-57.

47 Lowe JG. Scheuermann’s disease. Orthop Clin North Am. 1999;30:475-487.

48 Blumenthal SL, Roach J, Herring JA. Lumbar Scheuermann’s: A clinical series and classification. Spine. 1986;12:929-932.

49 Ogilvie JW, Sherman J. Spondylolysis in Scheuermann’s disease. Spine. 1987;12:251-253.

50 Heithoff KB, Gundry CR, Burton CV, et al. Juvenile discogenic disease. Spine. 1994;19:335-340.

51 Benli IT, Uzumcujil O, Aydin E, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities of neural axis in Lenke-type 1 idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2006;31:1828-1833.

52 Akhtar OH, Rowe DE. Syringomyelia-associated scoliosis with and without the Chiari-I malformation. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16:407-417.

53 Dimar JRII, Campbell M, Glassman SD, et al. Idiopathic juvenile osteoporosis: An unusual cause of back pain in an adolescent. Am J Orthop. 1995;24:865-869.

54 Smith R. Idiopathic juvenile osteoporosis: Experience of twenty-one patients. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34:68-77.

55 Tortolani PJ, McCarthy EF, Sponseller PD. Bone mineral density deficiency in children. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10:57-66.

56 Early SD, Kay RM, Tolo VT. Childhood diskitis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11:413-420.

57 Ring D, Johnston CEII, Wenger DR. Pyogenic infectious spondylitis in children: The convergence of discitis and vertebral osteomyelitis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15:652-660.

58 Song KS, Ogden JA, Ganey T, et al. Contiguous discitis and osteomyelitis in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1997;17:470-477.

59 Tay BKB, Deckey J, Hu S. Spinal infections. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10:188-197.

60 Mirovsky Y, Copeliovich L, Halperin N. Gowers’ sign in children with discitis of the lumbar spine. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2005;14:68-70.

61 Crawford AH, Kucharzyk DW, Ruda R, et al. Discitis in children. Clin Orthop. 1991;266:70-79.

62 Wenger DR, Bobechko WP, Gilday DL. The spectrum of intervertebral disc-space infection in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60:100-108.

63 Ring D, Wenger DR. Magnetic resonance imaging scans in discitis: Sequential studies in a child who needed operative drainage. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:596-601.

64 DuLac P, Panuel M, Devred P, et al. MRI of disc-space infection in infants and children: Report of 12 cases. Pediatr Radiol. 1990;20:175-178.

65 Glazer PA, Hu SS. Pediatric spinal infections. Orthop Clin North Am. 1996;27:111-123.

66 Garron E, Viehweger E, Launay F, et al. Nontuberculous spondylodiscitis in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22:321-328.

67 Hoffer FA, Strand RD, Gebhardt MC. Percutaneous biopsy of pyogenic infection of the spine in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1988;8:442-444.

68 Kayser R, Mahlfeld K, Greulich M, et al. Spondylodiscitis in childhood: Results of a long-term study. Spine. 2005;30:318-323.

69 Eismont FJ, Bohlman HH, Soni PL, et al. Vertebral osteomyelitis in infants. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1982;64:32-35.

70 Wrobel CJ, Chappell ET, Taylor W. Clinical presentation, radiological findings, and treatment results of coccidiomycosis involving the spine: Report on 23 cases. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:33-39.

71 Mushkin AY, Kovalenko KN. Neurological complications of spinal tuberculosis in children. Int Orthop. 1999;23:210-212.

72 Magnus KG, Hoffman EB. Pyogenic spondylitis and early tuberculous spondylitis in children: Differential diagnosis with standard radiographs and CT. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:539-543.

73 Morris BS, Varma R, Barg A, et al. Multifocal musculoskeletal tuberculosis in children: Appearances on CT. Skeletal Radiol. 2002;31:1-8.

74 Francis IM, Das DK, Luthra UK, et al. Value of radiologically guided fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) in the diagnosis of spinal tuberculosis. Cytopathology. 1999;10:390-401.

75 Blum U, Buitrago-Tellez C, Mundinger A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for detection of active sacroiliitis: A prospective study comparing conventional radiography, scintigraphy, and contrast enhanced MRI. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:2107-2115.

76 Kurugoglu S, Kanberoglu K, Kanberoglu A, et al. MRI appearances of inflammatory vertebral osteitis in early ankylosing spondylitis. Pediatr Radiol. 2002;32:191-194.

77 Stone M, Warren RW, Bruckel J, et al. Juvenile-onset ankylosing spondylitis is associated with worse functional outcomes than adult-onset ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:445-451.

78 Roger E, Letts M. Sickle cell disease of the spine in children. Can J Surg. 1999;42:289-292.

79 Onur O, Sitti A, Gumruk R, et al. Beta thalassaemia: A report of 20 children. Clin Rheumatol. 1999;18:42-44.

80 DiCaprio MR, Murphy MJ, Camp RL. Aneurysmal bone cyst of the spine with familial incidence. Spine. 2000;25:1589-1592.

81 Hay MC, Paterson D, Taylor TKF. Aneurysmal bone cysts of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1978;60:406-411.

82 Vergel De Dios AM, Bond JR, Shives TC, et al. Aneurysmal bone cysts: A clinicopathologic study of 238 cases. Cancer. 1992;69:2921-2931.

83 Cottalorda J, Kohler R, Sales de Gauzy G, et al. Epidemiology of aneurysmal bone cyst in children: A multicenter study and literature review. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2004;13:389-394.

84 Papagelopoulos PJ, Choudhoury SN, Frassica FJ, et al. Treatment of aneurysmal bone cysts of the pelvis and sacrum. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:1674-1681.

85 Papagelopoulos PJ, Currier BL, Shaughnessy WJ, et al. Aneurysmal bone cyst of the spine: Management and outcome. Spine. 1998;23:621-628.

86 DeCristofaro R, Biagini R, Boriani S, et al. Selective arterial embolization in the treatment of aneurysmal bone cyst and angioma of bone. Skeletal Radiol. 1992;21:523-527.

87 DeKleuver M, Van der Heul RO, Veraart BB. Aneurysmal bone cyst of the spine: 31 cases and the importance of the surgical approach. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1998;7:286-292.

88 DeRosa GP, Graziano GP, Scott J. Arterial embolization of aneurysmal bone cyst of the lumbar spine: A report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:777-780.

89 Berenstein A, Young W, Ransohoff J, et al. Somatosensory evoked potentials during spinal angiography and therapeutic transvascular embolization. J Neurosurg. 1984;60:777-785.

90 Ozaki T, Halm H, Hillmann A, et al. Aneurysmal bone cysts of the spine. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1999;119:159-162.

91 Garg SM, Mehta S, Dormans JP. Modern surgical treatment of primary aneurysmal bone cyst of the spine in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25:387-392.

92 Boriani S, DeLure F, Campanacci L, et al. Aneurysmal bone cyst of the mobile spine: Report on 41 cases. Spine. 2001;26:27-35.

93 Saifuddin A, White J, Sherazi Z, et al. Osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma of the spine: Factors associated with the presence of scoliosis. Spine. 1998;23:47-53.

94 Ozaki T, Liljenqvist U, Hillmann A, et al. Osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma of the spine: Experiences with 22 patients. Clin Orthop. 2002;397:394-402.

95 Lefton DR, Torrisi JM, Haller JO. Vertebral osteoid osteoma masquerading as a malignant bone or soft-tissue tumor on MRI. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:72-75.

96 Rajasekaran S, Kamath V, Shetty AP. Intraoperative Iso-C three-dimensional navigation in excision of spinal osteoid osteomas. Spine. 2008;33:E25-E29.

97 Baunin C, Puget C, Assoun J, et al. Percutaneous resection of osteoid osteoma under CT guidance in eight children. Pediatr Radiol. 1994;24:185-188.

98 Cove JA, Taminiau AH, Obermann WR, et al. Osteoid osteoma of the spine treated with percutaneous computed tomography-guided thermocoagulation. Spine. 2000;25:1283-1286.

99 Boriani S, Capanna R, Donati D, et al. Osteoblastoma of the spine. Clin Orthop. 1992;278:37-45.

100 Shaikh MI, Saifuddin A, Pringle J, et al. Spinal osteoblastoma: CT and MR imaging with pathological correlation. Skeletal Radiol. 1999;28:33-40.

101 Levine SE, Dormans JP, Meyer JS, et al. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis of the spine in children. Clin Orthop. 1996;323:288-293.

102 Floman Y, Bar-On E, Mosheiff R, et al. Eosinophilic granuloma of the spine. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1997;6:260-265.

103 Ghanem I, Tolo VT, D’Ambra P, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of bone in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23:124-130.

104 Papagelopoulos PJ, Currier BL, Galanis E, et al. Vertebra plana caused by primary Ewing sarcoma: Case report and review of the literature. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2002;15:252-257.

105 Willman CL, Busque L, Griffith BB, et al. Langerhans histiocytosis (histiocytosis X): A clonal proliferative disease. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:154-160.

106 Yeom JS, Lee CK, Shin HY, et al. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis of the spine: Analysis of 23 cases. Spine. 1999;24:1740-1749.

107 Garg S, Mehta S, Dormans JP. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis of the spine in children: Long-term followup. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:1740-1750.

108 Plasschaert F, Craig C, Bell R, et al. Eosinophilic granuloma: A different behaviour in children than in adults. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:870-872.

109 Mammano S, Candiotto S, Balsana M. Cast and brace treatment of eosinophilic granuloma of the spine: Long-term follow-up. J Pediatr Orthop. 1997;17:821-827.

110 Raab P, Hohmann F, Kuhl J, et al. Vertebral remodeling in eosinophilic granuloma of the spine: A long-term follow-up. Spine. 1998;23:1351-1354.

111 Rogalsky RJ, Black GB, Reed MH. Orthopaedic manifestations of leukemia in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68:494-501.

112 Kobayashi D, Satsuma S, Kamegaya M, et al. Musculoskeletal conditions of acute leukemia and malignant lymphoma in children. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2005;14:156-161.

113 Santangelo JR, Thomson JD. Childhood leukemia presenting with back pain and vertebral compression fractures. Am J Orthop. 1999;28:257-260.

114 Meehan PL, Viroslav S, Schmitt EW. Vertebral collapse in childhood leukemia. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15:592-595.

115 Kayser R, Mahlfeld K, Nebelung W, et al. Vertebral collapse and normal peripheral blood cell count at the onset of acute lymphatic leukemia in childhood. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2000;9:55-57.

116 Conrad EUIII, Olszewski AD, Berger M, et al. Pediatric spine tumors with spinal cord compromise. J Pediatr Orthop. 1992;12:454-460.

117 Martinez-Lage JF, Martinez Robledo A, Lopez F, et al. Disc protrusion in the child: Particular features and comparison with neoplasms. Childs Nerv Syst. 1997;13:201-207.

118 Garg S, Dormans JP. Tumors and tumor-like conditions of the spine in children. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13:372-381.

119 Shives TC, Dahlin DC, Sim FH, et al. Osteosarcoma of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68:660-668.

120 Dormans JP, Moroz L. Infection and tumors of the spine in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(Suppl):79-97.

121 Venkateswaran L, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Merchant TE, et al. Primary Ewing tumor of the vertebrae: Clinical characteristics, prognostic factors, and outcome. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001;37:30-35.

122 Grubb MR, Currier BL, Pritchard DJ. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the spine. Spine. 1994;19:309-313.

123 Leeson MC, Makely JT, Carter JR. Metastatic skeletal disease in the pediatric population. J Pediatr Orthop. 1985;5:261-267.

124 Lam CH, Nagib MG. Nonteratomatous tumors in the pediatric sacral region. Spine. 2002;27:E284-E287.

125 Parker AP, Robinson RO, Bullock P. Difficulties in diagnosing intrinsic spinal cord tumours. Arch Dis Child. 1996;75:204-207.

126 Pena M, Galasko CS, Barrie JL. Delay in diagnosis of intradural spinal tumors. Spine. 1992;17:1110-1116.

127 Newton HB, Newton CL, Gatens C, et al. Spinal cord tumors: Review of etiology, diagnosis, and multidisciplinary approach to treatment. Cancer Pract. 1995;3:207-218.

128 Mirovsky Y, Yakim I, Halperin N, et al. Non-specific back pain in children and adolescents: A prospective study until maturity. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2002;11:275-278.