Back Pain

Perspective

Back pain is a common symptom causing patients to seek care in the emergency department (ED). It accounts for 2.3% of all physician visits,1 and 84% of the adult population have experienced low back pain in their lifetime.2 Forty-nine percent have experienced low back pain in the last 6 months,2 and 26% in the last 3 months.1 Total costs of low back pain in the United States exceed $100 billion per year.3 Although mechanical or nonspecific low back is the most common cause, the differential diagnosis includes several life-threatening and disabling conditions (Box 35-1). Developing a systematic approach that screens all the potential causes of back pain is the key to accurate clinical decision-making.

Epidemiology

Ninety-seven percent of patients visiting a physician for evaluation of acute low back pain, defined as lasting less than 6 weeks, are ultimately diagnosed with mechanical or nonspecific low back pain.4 The vast majority of these are strain and degenerative in origin, but a few percent have herniated disk, spinal stenosis, fracture, and congenital disorders. Seventy-two percent will have completely recovered at 1 year.5 For those with chronic back pain, defined as lasting longer than 3 months, persistence or a recurrence within 12 months is very common.6 About 1% of all patients with back pain have true sciatica.6 Back pain is the second most common cause of lost time in the workplace and an enormous source of health care expenditures and lost productivity.7,8 The prevalence of chronic low back pain is rising.9

Before these common mechanical causes are considered, several emergent diagnoses should be excluded, including aortic dissection, abdominal aortic aneurysm, cauda equina syndrome, epidural abscess, osteomyelitis, and tumor. The presence of certain symptoms (Box 35-2) should prompt a more thorough examination of these possibilities. Visceral causes constitute about 2% of the diagnoses in patients with back pain.4 Aortic dissection is a rare but catastrophic event, with mortality rates exceeding 90% if it is not diagnosed. Cauda equina syndrome (bilateral leg pain and weakness, urinary retention with overflow incontinence, fecal incontinence or decreased rectal tone, and “saddle anesthesia”) is a rare but rapidly progressive disabling complication usually caused by a large central herniated disk and less often by tumor or infection. Epidural abscess and vertebral osteomyelitis constitute 0.01% of the diagnoses in patients complaining primarily of back pain.4 Spinal carcinoma is uncommon (0.7%) in the general population with back pain,4 but in cancer patients, 80% who report back pain have spinal metastases. Metastasis to bone is seen commonly in breast, lung, prostate, kidney, and thyroid carcinomas. Other tumors include primary bone cancers, multiple myeloma, lymphoma, and retroperitoneal tumors. Inflammatory arthritis is the diagnosis for 0.3% of patients with back pain.4

Pathophysiology

The gelatinous nucleus pulposus is surrounded by the tough anulus fibrosus. The anulus thins posteriorly, creating the opportunity for the nucleus pulposus to herniate. This varies from bulging to protrusion to extrusion to sequestration. Ninety-five percent of clinically significant herniations occur at the L4-5 and L5-S1 disk spaces, causing radicular pain in the L5 and S1 dermatomes.4 Involvement of the L5 nerve root manifests with decreased sensation in the first web space, weakness with extension of the great toe, but normal reflexes. An S1 radiculopathy is characterized by diminished sensation of the lateral foot and small toe, impaired plantar flexion, and a decreased or absent ankle jerk. Anatomic disk bulging (52-81%) and annular tears with focal disk protrusion (32-67%) usually do not cause symptoms, whereas disk extrusion (0-18%) is usually symptomatic.10–13 Serial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies show that two thirds of herniated disks regress or resolve over 6 months.4 Three fourths of patients’ symptoms improve within 6 weeks. In the absence of suspected cauda equina syndrome, computed tomography (CT) or MRI is not indicated in the evaluation of patients with suspected disk herniation. Many patients with a herniated disk improve over time, and many asymptomatic patients have radiographic findings, so imaging is not helpful and may be misleading. This natural resolution of symptoms in disk disease is in contrast to spinal stenosis, which tends to remain the same or worsen over time.4 The ligamentum flavum can thicken with age and along with degenerative changes contributes to spinal stenosis.

Diagnostic Approach

The emergency physician first evaluates for potential life-threatening and disabling causes of back pain, including thoracic aortic dissection, ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, epidural abscess or compressive mass, spinal column injury with cord or root compression, and cauda equina syndrome. An accurate history and physical examination guide the investigation of possible more serious underlying pathologic process (see Boxes 35-1 and 35-2).4 Laboratory tests and imaging are needed in some cases, but it is usually possible to rule out significant pathology without recourse to extensive testing.

Rapid Assessment and Stabilization

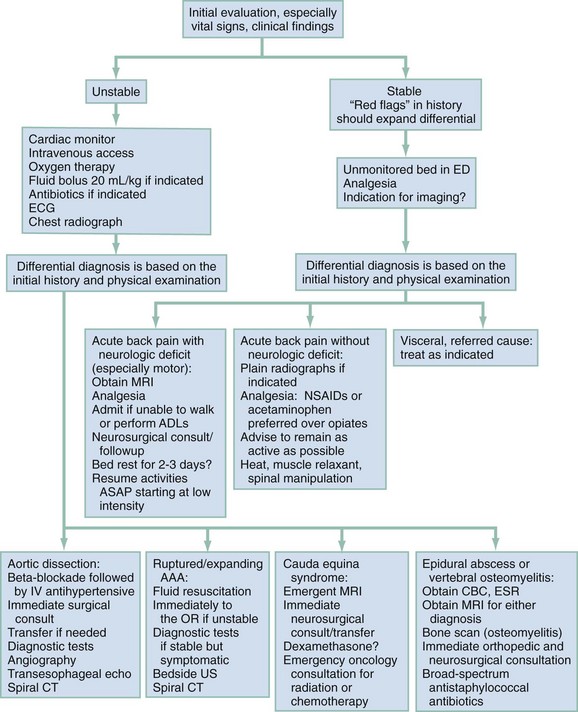

If the initial history and physical examination identify any suggestion of serious disease, rapid stabilization measures should ensue consistent with the cause of concern (Fig. 35-1). Management of aortic dissection, ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, and spinal cord and column injuries are covered in other chapters. If epidural abscess, hematoma, or cauda equina syndrome is suspected, emergent MRI is obtained, with neurosurgical consultation when indicated by the results of the scan. For epidural abscess, blood cultures are obtained, followed by intravenous administration of antibiotics against Staphylococcus aureus. For cauda equina syndrome,14 an urgent neurosurgical consultation is required. Once urinary retention occurs, the prognosis worsens and emergent spinal decompression is indicated. Although the evidence supporting steroid use is conflicting, dexamethasone is commonly used with the hope of decreasing compression from inflammation or to shrink tumor mass. For all patients with significant pain, including patients with “benign” causes for back pain, effective analgesia should be provided early in the evaluation.

Pivotal Findings

The history and physical examination should help sort patients into unstable and stable categories (see Fig 35-1). Certain findings will guide additional workup to discover causes for patients with neurologic deficits, and more serious spinal or visceral sources (see Box 35-2).

History

History of Present Illness.: The history helps to localize pain to the most likely structure and mechanism. The following questions are useful in differentiating between mechanical and nonmechanical causes and between unstable and stable patients and help guide appropriate management.

Where is the pain?: The patient is asked to point with one finger to the one spot where it hurts the most. Does the pain radiate, and if so, specifically where? Does the pain conform to a specific dermatomal area? Radicular pain, particularly extending below the knee in a dermatomal distribution, implies nerve root involvement. Sciatica radiates below the knees, causing focal motor and sensory loss. It worsens with bending, sitting, coughing, sneezing, and straining. Pain mainly in the paralumbar musculature without dermatomal radiculopathy implies nonspecific low back pain. Any associated chest or abdominal pain may indicate a visceral cause. Flank location implies a renal or retroperitoneal origin, and a higher location can be from the chest or pleura.

When did the pain start?: The patient should describe in detail what he or she was doing when the pain started. Has there been a recent change in type or intensity of physical activity? Is there any past history of back pain, and what therapeutic modalities were used to treat it? If there is a history of back pain, is there any difference between present and past pain? Acute onset associated with a specific task suggests a mechanical cause. Sudden-onset, severe back pain suggests a vascular cause. Slow onset or onset unrelated to activity suggests a nonmechanical cause (e.g., tumor). Nonmechanical pain may improve then recur, but the trend is progressive worsening.

Are there any aggravating or alleviating factors?: Cough or Valsalva maneuver that aggravates the pain in general favors a mechanical cause and may suggest a herniated disk. Back pain associated with tumors and infections often involves nighttime pain and persistent pain unrelieved by rest and analgesics. Spinal stenosis causes diffuse back pain, numbness, and tingling in one or both legs (pseudoclaudication). Symptoms are aggravated by ambulation (especially “downhill”) and relieved with spinal flexion (shopping cart sign), which increases spinal canal diameter, temporarily relieving the stenosis. Direct trauma may suggest contusion, strain, or fracture, whereas sudden deceleration is a risk for aortic dissection.

Is there motor or sensory loss, bowel or bladder dysfunction?: Back pain associated with progressive or severe neurologic symptoms, motor loss, urinary retention, or bowel incontinence requires MRI, which may indicate the need for emergent decompression.

Is there other pertinent history?: Other pertinent history should include past and present work history (a history of repeated loading would suggest mechanical cause); fever (suggesting infectious cause); medications (anticoagulants are associated with epidural hematomas, steroids are associated with infection and compression fractures); hematuria (suggesting nephrolithiasis or pyelonephritis); colic (nephrolithiasis, cholelithiasis); and pending litigation or worker’s compensation status (possible secondary gains).

Past Medical History.: In addition to any history of back disorders, a thorough inquiry about any systemic disease is important, including (1) cancer (metastatic disease), (2) inflammatory disease, (3) intravenous drug abuse (diskitis), (4) arthropathies, (5) endocrinopathies (hyperparathyroidism), (6) bleeding disorders, (7) osteoporosis, or (8) sickle cell disease. Previous atherosclerotic or vascular disease suggests aortic disease; previous kidney stones or alcohol-related disease may suggest related diseases. The medications or other modalities used to treat present and past symptoms may suggest possible treatment. Knowledge of current medications used by the patient gives clues about the presence of other systemic disease. Some diseases such as spondyloarthropathies (e.g., ankylosing spondylitis) have a familial component.

Physical Examination

Vital Signs.: Abnormal vital signs may suggest a life-threatening process (e.g., hypotension and tachycardia with ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, hypertension with aortic dissection, fever with abscess, osteomyelitis, or diskitis).

1. Observe the patient’s gait and movement in the examining room. Does the patient move cautiously, protecting himself or herself, or freely, appearing to be in little pain?

2. Examine the patient while he or she is standing, searching for scoliosis (may be structural or secondary to muscle spasm), increase or decrease in lumbar lordosis or thoracic kyphosis (may predispose to mechanical pain), or pelvic obliquity (may indicate muscle spasm, leg-length discrepancy, or uncompensated scoliosis).

3. Assess the range of motion for the low back. Significant mechanical pain usually worsens with flexion. Extension often eases pain caused by disk disease but may aggravate facet pain.

4. Perform the palpation in an orderly fashion with the fingertips to localize the area of greatest tenderness (e.g., specific spinous process; paravertebral musculature; sacroiliac joint suggesting inflammatory spondylitis).

Other Examinations, Including Neurologic Examination:

1. The neurologic assessment evaluates the asymmetry of reflexes (clinically, reflexes diminish with age, and uncovering asymmetry is key), dermatomal sensory loss, and focal muscle weakness (suggests nerve root impingement). If possible, motor testing of the legs is best done with the patient standing. Heel-walking and toe-walking indicate normal plantar and dorsiflexion strength, and a partial knee bend while bearing weight on one leg, then the other, indicates normal hip, buttock, and thigh muscle strength. A patient with a long history of back pain should be asked about previous motor, sensory, or reflex abnormality. The presence of clonus, hyper-reflexia, or upgoing toes (Babinski’s sign) indicates an upper motor neuron lesion.

2. A rectal examination can assess sphincter tone and anal wink. Testing for perianal sensation is necessary if there is any history of bowel or bladder dysfunction.

3. An examination for signs of systemic disease should include cardiac and pulmonary auscultation; abdominal examination for tenderness, aneurysm, or masses; and palpation of peripheral pulses.

4. The hips are examined for a musculoskeletal or inflammatory focus other than the back.

Straight Leg Raise.: The straight leg raise is the classic test for sciatic nerve root irritation. It is 92% sensitive but only 28% specific for disk disease.15 This test is often negative in patients with spinal stenosis. With the knee extended, the leg is elevated until pain is elicited. A positive result is pain radiating down the leg below the knee (not back, buttocks, or thigh pain) in a dermatomal distribution, reproductive of the patient’s symptoms, when the leg is elevated between 30 and 70 degrees. The crossed straight leg test (pain radiates below the knee on the side of nerve root irritation when the unaffected leg is raised) is only 28% sensitive but 90% specific for nerve root irritation on the contralateral side resulting from disk herniation. In a patient who may be malingering, the straight leg raise can be done with the patient sitting with the knees flexed at the side of the bed and then passively straightening the legs. If there is true nerve root irritation, results should be similar in the sitting and the supine positions.

Ancillary Testing

Laboratory Tests.: For mechanical causes of back pain, laboratory studies are of little use and are rarely ordered. For nonmechanical causes, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and white blood cell count are often obtained, but poor specificity, sensitivity, or both severely limit any meaningful interpretation of the results. Urinalysis is helpful in suspected cases of renal disease with referred back pain (nephrolithiasis, pyelonephritis, urinary tract infection).

Imaging.: Although patient satisfaction is reportedly higher when imaging is performed,16 early imaging is not useful and does not change management with uncomplicated mechanical low back pain of less than 6 weeks’ duration.17 Plain radiographs may be helpful if the patient has a history of trauma with bony tenderness. Pathologic fracture can occur with minimal or no trauma and is suspected in patients with rapid onset of back pain in the context of cancer, advanced age, osteoporosis, or prolonged glucocorticoid use,16 but plain radiographs should not be obtained if advanced imaging (e.g., CT, MRI) is planned. The vast majority of patients do not require radiographic evaluation in the ED.18,19

Whether to use plain film, CT, or MRI is influenced by several factors, including cost (plain film < CT < MRI), radiation exposure of the patient (MRI < plain film < CT), the detail of the information the imaging will provide (plain film < CT < MRI), and off-hours accessibility of an imaging modality at a particular facility (MRI < CT < plain film). Plain films give reasonable detail in showing fracture, particularly in the lumbar spine. However, CT will add greatly to bone detail over plain films. CT will often show additional lesser fractures after the plain film has already demonstrated the major fracture. The neurosurgeon or orthopedic surgeon will likely want CT or MRI after plain films have shown bone pathology in the back. In general, CT gives excellent bone detail and only moderate detail of soft tissue. MRI gives excellent detail of soft tissue and only moderate detail of bone. Plain film is used for straightforward evaluation for fracture, or as a screening tool for other issues when the prior probability of serious injury or pathology is low. CT is used if a spine fracture has been identified or a more complex fracture is suspected. MRI is used if a disk condition, hematoma, infection, or a mass is suspected to be the cause of the problem. Emergency MRI, CT, or, rarely, myelogram (in order of preference) is indicated if an acute, significant neurologic deficit such as motor loss, loss of reflexes, cauda equina syndrome, or one of the serious nonmechanical back pain sources is suspected.19,20 It can be difficult to differentiate true motor weakness from apparent weakness caused by pain during motor testing. For patients with acute back and radicular pain but no motor weakness and for those with chronic low back pain without neurologic deficit, use of MRI and CT increases costs and radiation exposure but does not improve outcome.21–23 The majority of patients with sciatica recover without surgery.24 Patients with chronic low back pain or radiculopathy without motor loss should undergo MRI or CT only if surgery or epidural steroid injection is indicated.19 For patients in whom infection or tumor is suspected, MRI (or bone scan followed by MRI) is the diagnostic test of choice.25 The degree of neurologic impairment, duration, and rate of worsening dictate whether these tests are performed on an emergent or urgent basis. If the motor loss in a muscle segment is rapidly progressive or 3/5 or less, MRI and neurosurgical consultation should be undertaken emergently. If motor loss is subacute, stable, and with 4/5 strength, it is possible to wait a day or two for imaging, with neurosurgical follow-up soon after. This should be arranged with the on-call neurosurgeon and medical imaging. The patient is instructed to return sooner if worsening weakness occurs.

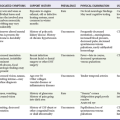

Differential Diagnosis

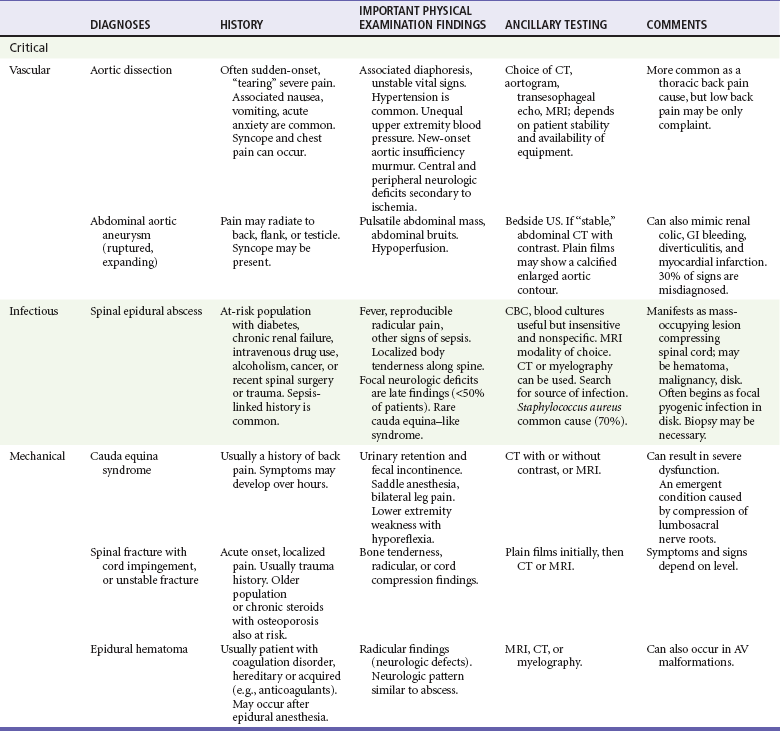

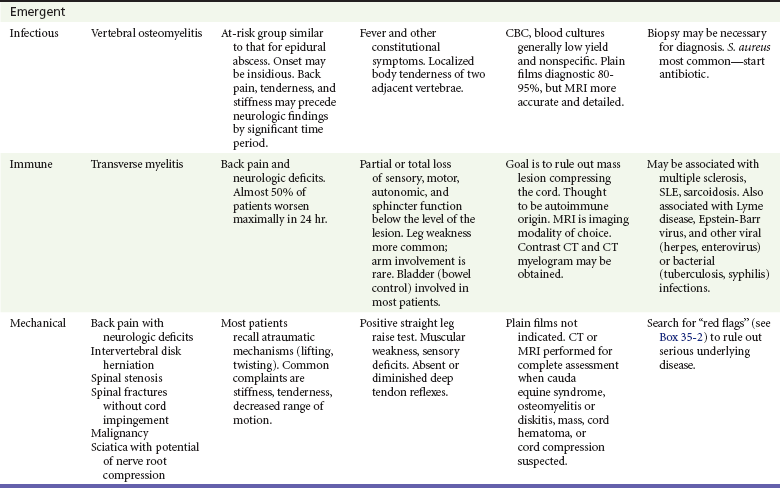

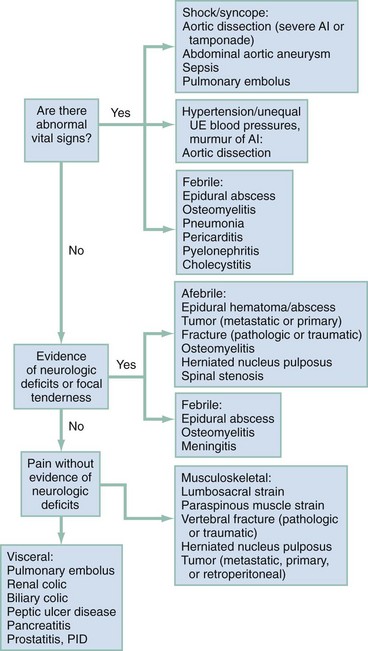

After stabilization and assessment, the clinical findings aid in narrowing the differential diagnosis (Table 35-1). An algorithm (see Fig. 35-1) that takes into account important differential considerations, such as abnormal vital signs, the presence of fever, and an abnormal neurologic examination, is a useful tool. After collecting this information, the emergency physician should be able to answer two additional key questions: Does the patient need emergent, urgent, or routine treatment? Does the patient need surgical or medical treatment? Young children with no clear explanation for their back pain should have early and more extensive evaluation for infection and tumor.

Empirical Management

The initial empirical management of acute back pain depends on the presenting vital signs and the patient’s overall appearance. Figure 35-2 details the specific management considerations for treating unstable patients.14,26–29 For a stable patient, early effective pain management can be of significant value. The choice of analgesic is dictated by the patient’s and physician’s perception of the degree of pain. Physicians notoriously underestimate and undertreat acute pain. If the pain is severe, intravenous opioids such as morphine or hydromorphone are the preferred analgesic and should be given in a titrated fashion. Frequent reassessment of the patient for an adequate response is required. After adequate response to the initial intravenous opioid, an oral agent can be administered in preparation for discharge. For patients with less severe symptoms, the first choice should be acetaminophen or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID).19 NSAIDs are effective for short-term relief of acute low back pain but are not superior to acetaminophen.30 Their safety profiles are considered in patients with acid peptic disease, renal insufficiency, diabetes, and cardiac or liver pathology. A short course of an oral opioid may be necessary. Benzodiazepines are often prescribed as an adjunct to opioid and nonopioid analgesia, and their anxiolytic and sedative properties may promote sleep and synergize pain relief. There is no credible evidence supporting the use or effectiveness of “muscle relaxants” or “antispasmodic agents,” such as methocarbamol (Robaxin and others) and cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril), and they have significant adverse effects.31,32 The best approach is to provide adequate analgesia for the patient, supplemented by a benzodiazepine when the pain syndrome is particularly severe. Other interventions shown to be effective include advice to be as active as pain allows,33 heat,34 and spinal manipulation (in highly selected cases).35–37

For some patients, chronic recurrent mechanical back pain is a long-term issue, and they may visit the ED during an acute exacerbation. Such patients need support and often a multidisciplinary approach to help manage their chronic pain or recurrent flare-ups. Management requires referral and follow-up at primary care or a pain clinic. This approach is discussed in Chapter 3. Primary care or pain management clinics often use adjuncts, such as lumbar supports,38 traction,39 acupuncture,40 spinal manipulative therapy,35 physical therapy or chiropractic therapy,36,37 back education,19,41 massage,42 exercise therapy,43,44 transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS),45 heat therapy,34 cognitive behavioral therapy,46 epidural injection of methylprednisolone,47 gabapentin for lumbar stenosis,48 duloxetine,49 and tricyclic or tetracyclic antidepressant therapy.50 Evidence for most of these treatments is modest, at best.

Disposition

Patients who are unable to walk or require continued intravenous analgesics for adequate pain control should be considered for admission to the hospital or the ED observation unit. If pain can be adequately controlled with oral analgesics, patients can be discharged with appropriate follow-up. Encourage patients to maintain activities as their pain allows, avoiding heavy lifting or twisting during the acute phase. Reassure the patient with acute mechanical back pain that the vast majority of patients eventually experience spontaneous relief of pain. Prescribe NSAIDs or acetaminophen, supplemented with short-course oral opioids for moderate to severe pain, and refer the patient for primary care. Oral opioids are highly effective for short-term relief and should be prescribed in adequate doses. With chronic back pain, however, opioid efficacy is less clear, and aberrant medication taking occurs in up to 24% of cases.51,52 Repeat visits to the ED for chronic back pain should prompt counseling of the patient regarding the necessity of management by the primary care physician or a pain management center. Opioid medication should not be administered or prescribed in the ED for such patients, absent a new, acute condition. In the chronic back pain population, prescription opioid abuse is epidemic. For such patients, simple analgesics such as NSAIDs are indicated. (See Chapters 3 and 189.) Patients should be advised to avoid strict or prolonged bed rest, as it is no more effective and may be worse than maintaining reasonable activities.33

References

1. Deyo, RA, Mirza, SK, Martin, BI. Back pain prevalence and visit rates: Estimates from U.S. national surveys, 2002. Spine. 2006;31:2724.

2. Cassidy, JD, Carroll, LJ, Côté, P. The Saskatchewan health and back pain survey: The prevalence of low back pain and related disability in Saskatchewan adults. Spine. 1998;23:1860.

3. Katz, JN. Lumbar disc disorders and low-back pain: Socioeconomic factors and consequences. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(Suppl 2):21.

4. Deyo, RA, Weinstein, JN. Primary care: Low back pain. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:363.

5. Henschke, N, et al. Prognosis in patients with recent onset low back pain in Australian primary care: Inception cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a171.

6. Borenstein, DG. Epidemiology, etiology, diagnostic evaluation, and treatment of low back pain. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1999;11:151.

7. Stewart, WF, Ricci, JA, Chee, E, Morganstein, D, Lipton, R. Lost productive time and cost due to common pain conditions in the U.S. workforce. JAMA. 2003;290:2443.

8. Luo, X, Pietrobon, R, Sun, SX, Liu, GG, Hey, L. Estimates and patterns of direct health care expenditures among individuals with back pain in the United States. Spine. 2004;29:79.

9. Freburger, JK, et al. The rising prevalence of chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:251.

10. Jarvik, JJ, Hollingworth, W, Heagerty, P, Haynor, DR, Deyo, RA. The longitudinal assessment of imaging and disability of the back (LAIDBack) study: Baseline data. Spine. 2001;26:1158.

11. Jensen, MC, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:69.

12. Stadnik, TW, et al. Annular tears and disk herniation: Prevalence and contrast enhancement on MR images in the absence of low back pain or sciatica. Radiology. 1998;206:49.

13. Weishaupt, D, Zanetti, M, Hodler, J, Boos, N. MR imaging of the lumbar spine: Prevalence of intervertebral disk extrusion and sequestration, nerve root compression, end plate abnormalities, and osteoarthritis of the facet joints in asymptomatic volunteers. Radiology. 1998;209:661.

14. Lavy, C, James, A, Wilson-MacDonald, J, Fairbank, J. Cauda equine syndrome. BMJ. 2009;338:b936.

15. van der Windt, D, et al. Physical examination for lumbar radiculopathy due to disc herniation in patients with low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 17, 2010.

16. Kendrick, D, et al. Radiography of the lumbar spine in primary care patients with low back pain: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2001;322:400.

17. Chou, R, Fu, R, Carrino, JA, Deyo, RA. Imaging strategies for low back pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:463.

18. Atlas, SJ, Deyo, RA. Evaluating and managing acute low back pain in the primary care setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:120.

19. Chou, R, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: A joint clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:478.

20. Chou, R, et al. Diagnostic imaging for low back pain: Advice for high-value health care from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:181.

21. Gilbert, FJ, et al. Low back pain: Influence of early MR imaging or CT on treatment and outcome-multicenter randomized trial. Radiology. 2004;231:342.

22. Modic, MT, et al. Acute low back pain and radiculopathy: MR imaging findings and their prognostic role and effect on outcome. Radiology. 2005;237:597.

23. Jarvik, JG, et al. Rapid magnetic resonance imaging vs radiographs for patients with low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2810.

24. Peul, WC, et al. Surgery versus prolonged conservative treatment for sciatica. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2245.

25. Joines, JD, McNutt, RA, Carey, TS, Deyo, RA, Rouhani, R. Finding cancer in primary care outpatients with low back pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:14.

26. Hiratzka, LF, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with thoracic aortic disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:e27–e129.

27. Hirsch, AT, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1239.

28. Darouiche, RO. Spinal epidural abscess. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2012.

29. Frohman, EM, Wingerchuk, DM. Clinical practice. Transverse myelitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:564.

30. Roelofs, PD, Deyo, RA, Koes, BW, Scholten, RJ, van Tulder, MW. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, 2008.

31. Chou, R, Peterson, K, Helfand, M. Comparative efficacy and safety of skeletal muscle relaxants for spasticity and musculoskeletal condition: A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:140.

32. van Tulder, MW, Touray, T, Furlan, AD, Solway, S, Bouter, LM. Muscle relaxants for non-specific low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2003.

33. Dahm, KT, Brurberg, KG, Jamtvedt, G, Hagen, KB. Advice to rest in bed versus advice to stay active for acute low-back pain and sciatica. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 6, 2010.

34. French, SD, Cameron, M, Walker, BF, Reggars, JW, Esterman, AJ. Superficial heat or cold for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, 2006.

35. Assendelft, WJ, Morton, SC, Yu, EI, Suttorp, MJ, Shekelle, PG. Spinal manipulative therapy for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, 2004.

36. Cherkin, DC, Sherman, KJ, Deyo, RA, Shekelle, PG. A review of the evidence for the effectiveness, safety and cost of acupuncture, massage therapy, and spinal manipulation for back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:898.

37. Walker, BF, French, SD, Grant, W, Green, S. Combined chiropractic interventions for low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, 2010.

38. van Duijvenbode, IC, Jellema, P, van Poppel, MN, van Tulder, MW. Lumbar supports for prevention and treatment of low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2008.

39. Clarke, JA, et al. Traction for low-back pain with or without sciatica. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, 2005.

40. Furlan, AD, et al. Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, 2008.

41. Engers, A, et al. Individual patient education for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, 2008.

42. Furlan, AD, Imamura, M, Dryden, T, Irvin, E. Massage for low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, 2008.

43. Hayden, JA, van Tulder, MW, Malmivaara, A, Koes, BW. Exercise therapy for treatment of non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3, 2005.

44. Choi, BK, Verbeek, JH, Tam, WW, Jiang, JY. Exercises for prevention of recurrences of low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, 2010.

45. Khadilkar, A, Odebiyi, DO, Brosseau, L, Wells, GA. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3, 2005.

46. Linton, SJ, Andersson, T. Can chronic disability be prevented? A randomized trial of a cognitive behavior intervention and two forms of information for patients with spinal pain. Spine. 2000;25:2825.

47. Wilson-MacDonald, J, Burt, G, Griffin, D, Glynn, C. Epidural steroid injection for nerve root compression: A randomised, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:352.

48. Yaksi, A, Ozgönenel, L, Ozgönenel, B. The efficiency of gabapentin therapy in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 2007;32:939.

49. Skijarevski, V, et al. Efficacy and safety of duloxetine in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine. 2010;35:e578.

50. Staiger, TO, Gaster, B, Sullivan, MD, Deyo, RA. Systematic review of antidepressants in the treatment of chronic low back pain. Spine. 2003;28:2540.

51. Deshpande, A, Furlan, A, Mailis-Gagnon, A, Atlas, S, Turk, D. Opioids for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, 2008.

52. Martell, BA, et al. Systematic review: Opioid treatment for chronic back pain: prevalence, efficacy, and association with addiction. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:116.