Problem 52 Back and leg pain in a middle-aged man

The clinical picture fits for an acute neurological problem.

Q.4

How should the patient be investigated?

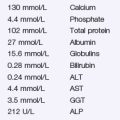

An investigation is performed as shown in Figures 52.1–52.3.

Answers

Further history should be directed towards excluding:

A.2 On physical examination evidence should be sought of overall state of health, e.g.:

Specific features referable to the symptoms and the need to be excluded:

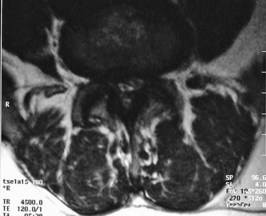

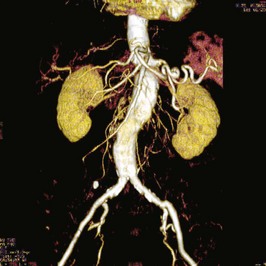

The sagittal MRI of this patient (Figure 52.1) reveals two problems. First, the patient has a congenitally narrow spinal canal. Any disc prolapse is more likely to cause a cauda equina compressive syndrome. Second, the patient has an L4/5 disc prolapse (Figure 52.2) which explains his clinical presentation. This compresses the thecal sac to the extent that little CSF is visible at this level. This compression leads to compromise of the nerve roots which form the cauda equina. Figure 52.3 is at the level of L3/4 disc and shows the normal appearance of the thecal sac and spinal canal.

Revision Points