B

Backward failure, see Cardiac failure

Baclofen. Synthetic GABAB receptor agonist and skeletal muscle relaxant, used to treat muscle spasticity, e.g. following spinal injury and in multiple sclerosis. Acts at both spinal and supraspinal levels. Has also been used to treat alcohol withdrawal syndromes.

Bacteraemia. Presence of bacteria in the blood. May be present in SIRS and sepsis, but is not necessary for either diagnosis to be made.

Bacteria. Micro-organisms with a bilayered cytoplasmic membrane, a double-stranded loop of DNA and, in most cases, an outer cell wall containing muramic acid. Responsible for many diseases; mechanisms include the initiation of inflammatory pathways by endotoxins or exotoxins; direct toxic effects on/destruction of tissues or organ systems; impairment of host defensive mechanisms; invasion of host cells; and provocation of autoimmune processes. Early claims that bacterial infections had been conquered by the development of antibacterial drugs are now seen as premature in light of the increasing problem of bacterial resistance. Classified according to their ability to be stained by crystal violet after iodine fixation and alcohol decolorisation (Gram staining), various aspects of their metabolism and their morphology:

– aerobes:

– cocci (spherical-shaped), e.g. staphylococci, enterococci, streptococci species.

– bacilli (rod-shaped), e.g. bacillus, corynebacterium, mycobacterium species.

– cocci, e.g. peptococcus species.

– bacilli, e.g. actinomyces, propionibacterium, clostridium species.

– aerobes:

– cocci, e.g. neisseria species.

Bacterial contamination of breathing equipment, see Contamination of anaesthetic equipment

Bacterial resistance. Ability of bacteria to survive in the presence of antibacterial drugs. An increasingly significant problem in terms of cost, pressure on development of new antibiotics and impaired ability to treat infections both in critically ill patients and the community as a whole.

impermeability of the cell wall to the drug, e.g. pseudomonas and many antibiotics.

impermeability of the cell wall to the drug, e.g. pseudomonas and many antibiotics.

lack of intracellular binding site for the antibiotic, e.g. Streptococcus pneumoniae and penicillin resistance.

lack of intracellular binding site for the antibiotic, e.g. Streptococcus pneumoniae and penicillin resistance.

lack of target metabolic pathways, e.g. vancomycin is only effective against Gram-positive organisms because it affects synthesis of the peptidoglycan cell wall components that Gram-negative bacteria do not possess.

lack of target metabolic pathways, e.g. vancomycin is only effective against Gram-positive organisms because it affects synthesis of the peptidoglycan cell wall components that Gram-negative bacteria do not possess.

production of specific enzymes against the drug, e.g. penicillinase.

production of specific enzymes against the drug, e.g. penicillinase.

Factors that increase the likelihood of resistance occurring include indiscriminate use of antibacterial drugs, inappropriate choice of drug and use of suboptimal dosage regimens (including poor compliance by users, e.g. long-term anti-TB drug therapy). Regular consultation with microbiologists, use of antibiotic guidelines and infection control procedures, and microbiological surveillance may limit the problem. In the UK, the Department of Health has run several campaigns to increase awareness of the problem and encourage sensible prescribing of antibiotics. ‘Antimicrobial stewardship’ programmes (particularly in ITUs) strive to reduce the emergence of bacterial resistance, improve clinical outcomes and control costs, through the logical prescribing of antibacterial drugs.

Resistance may also occur in other micro-organisms, although the problem is greatest in bacteria.

Gandhi TN, DePestel DD, Collins CD, Nagel J, Washer LL (2010). Crit Care Med; 38 (Suppl.): S315–23

Bacterial translocation. Passage of bacteria across the bowel wall via lymphatics into the hepatic portal circulation, and thence possibly into the systemic circulation. Implicated in the pathophysiology of intra-abdominal or generalised sepsis and MODS, with increased bowel wall permeability resulting from inadequate oxygen delivery allowing bacteria or their components (e.g. endotoxins) to enter the circulation and activate various inflammatory mediator pathways, including cytokines. The inflammatory response may thus be initiated or maintained. Resting the bowel is thought to increase the chances of bacterial translocation; therefore early enteral feeding of critically ill patients (especially with a glutamine-enriched feed) is believed to be beneficial.

Although much evidence supports the occurrence of bacterial translocation, its actual significance in SIRS and MODS is disputed.

Bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein. Protein normally released by activated polymorphonuclear leucocytes. Binds to and neutralises endotoxin and is bactericidal against Gram-negative organisms (by increasing permeability of bacterial cell walls). May have a role in the future treatment of severe Gram-negative infections, e.g. meningococcal disease. Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein is closely related.

See also, Sepsis; Sepsis syndrome; Septic shock; Systemic inflammatory response syndrome

Bain breathing system, see Coaxial anaesthetic breathing systems

Bainbridge reflex. Reflex tachycardia following an increase in central venous pressure, e.g. after rapid infusion of fluid. Activation of atrial stretch receptors results in reduced vagal tone and tachycardia. Absent or diminished if the initial heart rate is high. Of uncertain significance but has been proposed to be involved in respiratory sinus arrhythmia and to act as a counterbalance to the baroreceptor reflex.

Balanced anaesthesia. Concept of using a combination of drugs and techniques (e.g. general and regional anaesthesia) to provide adequate analgesia, anaesthesia and muscle relaxation (triad of anaesthesia). Each drug reduces the requirement for the others, thereby reducing side effects due to any single agent, while also allowing faster recovery. Arose from Crile’s description of anociassociation in 1911, and Lundy’s refinement in 1926.

Ballistocardiography. Obsolete method for measurement of measure cardiac output and stroke volume via detection of body motion resulting from movement of blood within the body with each heartbeat.

Balloon pump, see Intra-aortic counter-pulsation balloon pump

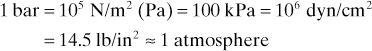

Bar. Unit of pressure. Although not an SI unit, commonly used when referring to the pressures at which anaesthetic gases are delivered from cylinders and piped gas supplies.

Baralyme. Calcium hydroxide 80% and barium octahydrate 20%. Used to absorb CO2. Although less efficient than soda lime, it produces less heat and is more stable in dry atmospheres. Used in spacecraft. Carbon monoxide production may occur when volatile agents containing the CHF2 moiety (desflurane, enflurane or isoflurane) are passed over dry warm baralyme, e.g. at the start of a Monday morning operating session following prolonged passage of dry gas through the absorber.

Barbiturate poisoning. Causes CNS depression with hypoventilation, hypotension, hypothermia and coma.

Skin blisters and muscle necrosis may also occur.

general measures as for poisoning and overdoses.

general measures as for poisoning and overdoses.

forced alkaline diuresis, dialysis or haemoperfusion may be indicated.

forced alkaline diuresis, dialysis or haemoperfusion may be indicated.

Barbiturates. Drugs derived from barbituric acid, itself derived from urea and malonic acid and first synthesised in 1864. The first sedative barbiturate, diethyl barbituric acid, was synthesised in 1903. Many others have been developed since, including phenobarbital in 1912, hexobarbital in 1932 (the first widely used iv barbiturate), thiopental in 1934, and methohexital (methohexitone) in 1957.

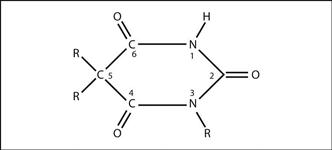

• Substitutions at certain positions of the molecule confer hypnotic or other properties to the compound (Fig. 22). Chemical classification:

oxybarbiturates: as shown. Slow onset and prolonged action, e.g. phenobarbital.

oxybarbiturates: as shown. Slow onset and prolonged action, e.g. phenobarbital.

Exist in two structural isomers, the enol and keto forms. The enol form is water-soluble at alkaline pH and undergoes dynamic structural isomerism to the lipid-soluble keto form upon exposure to physiological pH (e.g. after injection).

long-acting, e.g. phenobarbital.

long-acting, e.g. phenobarbital.

medium-acting, e.g. amobarbital.

medium-acting, e.g. amobarbital.

very short-acting, e.g. thiopental.

very short-acting, e.g. thiopental.

• Bind avidly to the alpha subunit of the GABAA receptor, potentiating the effects of endogenous GABA. Antagonism of AMPA-type glutamate receptors (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors) also contributes to CNS depression. Actions:

general CNS depression, especially cerebral cortex and ascending reticular activating system.

general CNS depression, especially cerebral cortex and ascending reticular activating system.

central respiratory depression (dose-related).

central respiratory depression (dose-related).

reduction of rapid eye movement sleep (with rebound increase after cessation of chronic use).

reduction of rapid eye movement sleep (with rebound increase after cessation of chronic use).

anticonvulsant or convulsant properties according to structure.

anticonvulsant or convulsant properties according to structure.

Oxidative and conjugative hepatic metabolism is followed by renal excretion. Cause hepatic enzyme induction.

Used mainly for induction of anaesthesia, and as anticonvulsant drugs. Have been replaced by benzodiazepines for use as sedatives and hypnotics, as the latter drugs are safer.

See also, γ-Aminobutyric acid receptors; Barbiturate poisoning

Bariatric surgery. Performed to induce significant and sustained weight loss in severe obesity, thereby preventing and indirectly treating the complications of obesity. Delivered as part of a multidisciplinary programme including diet/lifestyle modifications ± drug therapy.

• Indications (issued by NICE):

body mass index (BMI) ≥ 40 kg/m2 or 35–40 kg/m2 in the presence of related significant disease (e.g. diabetes, hypertension), where non-surgical measures have failed and patients are fit enough for anaesthesia and surgery.

body mass index (BMI) ≥ 40 kg/m2 or 35–40 kg/m2 in the presence of related significant disease (e.g. diabetes, hypertension), where non-surgical measures have failed and patients are fit enough for anaesthesia and surgery.

BMI > 50 kg/m2 as first-line treatment, if patients are fit enough for anaesthesia and surgery.

BMI > 50 kg/m2 as first-line treatment, if patients are fit enough for anaesthesia and surgery.

malabsorptive: biliopancreatic diversion ± duodenal switch.

malabsorptive: biliopancreatic diversion ± duodenal switch.

restrictive/malabsorptive: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (laparoscopic or open).

restrictive/malabsorptive: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (laparoscopic or open).

Anaesthetic considerations are as for all patients with morbid obesity.

Barker, Arthur E (1850–1916). English Professor of Surgery at University of London. Helped popularise spinal anaesthesia in the UK. In 1907, became the first to use hyperbaric solutions of local anaesthetic agents, combined with alterations in the patient’s posture, to vary the height of block achieved. Studied the effects of baricity of various local anaesthetic preparations by developing a glass spine model. Used specially prepared solutions of stovaine (combined with 5% glucose) from Paris.

Baroreceptor reflex (Pressoreceptor, Carotid sinus or Depressor reflex). Reflex involved in the short-term control of arterial BP. Increased BP stimulates baroreceptors in the carotid sinus and aortic arch, increasing afferent discharge in the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves respectively, that is inhibitory to the vasomotor centre and excitatory to the cardioinhibitory centre in the medulla. Vasomotor inhibition (reduced sympathetic activity) and increased cardioinhibitory activity (vagal stimulation) result in a lowering of BP and heart rate. The opposite changes occur following a fall in BP, with sympathetic stimulation and parasympathetic inhibition. Resultant peripheral vasoconstriction occurs mainly in non-vital vascular beds, e.g. skin, muscle, GIT.

The reflex is reset within 30 min if the change in BP is sustained. It may be depressed by certain drugs, e.g. halothane and possibly propofol.

Baroreceptors. Stretch mechanoreceptors in the walls of blood vessels and heart chambers. Respond to distension caused by increased pressure, and are involved in control of arterial BP.

carotid sinus and aortic arch:

carotid sinus and aortic arch:

– send afferent impulses via the carotid sinus nerve (branch of glossopharyngeal nerve) and vagus (afferents from aortic arch) to the vasomotor centre and cardioinhibitory centre in the medulla. Raised BP invokes the baroreceptor reflex.

– found in both atria. Involved in both short-term neural control of cardiac output and long-term humoral control of ECF volume.

– some discharge during atrial systole while others discharge during diastolic distension (more so when venous return is increased or during IPPV). The latter may be involved in the Bainbridge reflex. Discharge also results in increased urine production via stimulation of ANP secretion and inhibition of vasopressin release.

ventricular stretch receptors: stimulation causes reduced sympathetic activity in animals, but the clinical significance is doubtful. May also respond to chemical stimulation (Bezold–Jarisch reflex).

ventricular stretch receptors: stimulation causes reduced sympathetic activity in animals, but the clinical significance is doubtful. May also respond to chemical stimulation (Bezold–Jarisch reflex).

Other baroreceptors may be present in the mesentery, affecting local blood flow.

Barotrauma. Physical injury caused by an excessive pressure differential across the wall of a body cavity; in anaesthesia, the term usually refers to pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pneumoperitoneum or subcutaneous emphysema resulting from passage of air from the tracheobronchial tree and alveoli into adjacent tissues. Risk of barotrauma is increased by raised airway pressures, e.g. with IPPV and PEEP (especially if excessive tidal volume or air flow is delivered, or if the patient fails to synchronise with the ventilator). High frequency ventilation may reduce the risk. Diseased lungs with reduced compliance are more at risk of developing barotrauma, e.g. in asthma, ARDS; limiting inspiratory pressures at the expense of reduced minute volume and increased arterial PCO2 is increasingly used to reduce the risk of barotrauma in these patients (permissive hypercapnia). Evidence of pulmonary interstitial emphysema may be seen on the CXR (perivascular air, hilar air streaks and subpleural air cysts) before development of severe pneumothorax. In all cases, N2O will aggravate the problem.

Risk of barotrauma during anaesthesia is reduced by various pressure-limiting features of anaesthetic machines and breathing systems.

See also, Emphysema, subcutaneous; Ventilator-associated lung injury

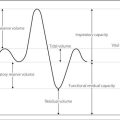

Basal metabolic rate (BMR). Amount of energy liberated by catabolism of food per unit time, under standardised conditions (i.e. a relaxed subject at comfortable temperature, 12–14 h after a meal). May be expressed corrected for body surface area.

O2 consumption: the subject breathes via a sealed circuit (containing a CO2 absorber) from an O2-filled spirometer. As O2 is consumed, the volume inside the spirometer falls, and a graph of volume against time is obtained. O2 consumption per unit time is corrected to standard temperature and pressure. Average energy liberated per litre of O2 consumed = 20.1 kJ (4.82 Cal; some variation occurs with different food sources); thus BMR may be calculated. A similar derivation can be obtained electronically by the bedside ‘metabolic cart’, e.g. when calculating energy balance in critically ill patients.

O2 consumption: the subject breathes via a sealed circuit (containing a CO2 absorber) from an O2-filled spirometer. As O2 is consumed, the volume inside the spirometer falls, and a graph of volume against time is obtained. O2 consumption per unit time is corrected to standard temperature and pressure. Average energy liberated per litre of O2 consumed = 20.1 kJ (4.82 Cal; some variation occurs with different food sources); thus BMR may be calculated. A similar derivation can be obtained electronically by the bedside ‘metabolic cart’, e.g. when calculating energy balance in critically ill patients.

• Metabolic rate is increased by:

circulating catecholamines, e.g. due to stress.

circulating catecholamines, e.g. due to stress.

recent feeding (specific dynamic action of foods).

recent feeding (specific dynamic action of foods).

Measurement of metabolic rate under basal conditions eliminates many of these variables.

Basal narcosis, see Rectal administration of anaesthetic agents

Base. Substance that can accept hydrogen ions, thereby reducing hydrogen ion concentration.

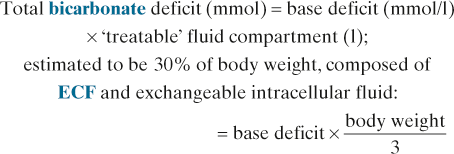

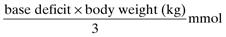

Base excess/deficit. Amount of acid or base (in mmol) required to restore 1 litre of blood to normal pH at PCO2 of 5.3 kPa (40 mmHg) and at body temperature. By convention, its value is negative in acidosis and positive in alkalosis. May be read from the Siggaard-Andersen nomogram. Useful as an indication of severity of the metabolic component of acid–base disturbance, and in the calculation of the appropriate dose of acid or base in its treatment. For example, in acidosis:

See also, Acid–base balance; Blood gas analyser; Blood gas interpretation

Basic life support, adult (BLS). Component of CPR without any equipment or drugs (i.e. suitable for anyone to administer). Known as the ‘ABC’ of resuscitation. Use with simple equipment, e.g. airways, facemasks, self-inflating bags, oesophageal obturators, LMA; it has been defined as ‘basic life support with airway adjuncts’. Latest European recommendations (2010):

ensure own safety and that of the victim.

ensure own safety and that of the victim.

Breathing: check first – look, listen and feel for up to 10 s. If breathing, turn into the recovery position, unless spinal cord injury is suspected. Summon help, asking for an automated external defibrillator (AED) if one is available; a solo rescuer should ‘phone first’ since the chance of successful defibrillation falls with increasing delay (although children, trauma or drowning victims, and poisoned or choking patients may benefit from 1 min of CPR before calling for help). If not breathing, summon help and, on returning, start cardiac massage; after 30 compressions give two slow effective breaths (700–1000 ml, each over 1 s) followed by another 30 compressions. Rapid breaths are more likely to inflate the stomach. Cricoid pressure should be applied if additional help is available. Risk of HIV infection and hepatitis is considered negligible. Inflating equipment and 100% O2 should be used if available.

Breathing: check first – look, listen and feel for up to 10 s. If breathing, turn into the recovery position, unless spinal cord injury is suspected. Summon help, asking for an automated external defibrillator (AED) if one is available; a solo rescuer should ‘phone first’ since the chance of successful defibrillation falls with increasing delay (although children, trauma or drowning victims, and poisoned or choking patients may benefit from 1 min of CPR before calling for help). If not breathing, summon help and, on returning, start cardiac massage; after 30 compressions give two slow effective breaths (700–1000 ml, each over 1 s) followed by another 30 compressions. Rapid breaths are more likely to inflate the stomach. Cricoid pressure should be applied if additional help is available. Risk of HIV infection and hepatitis is considered negligible. Inflating equipment and 100% O2 should be used if available.

in cases of choking, encourage coughing in conscious patients; clear the airway manually and use ≤ 5 back slaps then ≤ 5 abdominal thrusts (Heimlich manoeuvre) if not breathing or unable to speak, repeated as necessary; use basic life support (as above) if the patient becomes unconscious.

in cases of choking, encourage coughing in conscious patients; clear the airway manually and use ≤ 5 back slaps then ≤ 5 abdominal thrusts (Heimlich manoeuvre) if not breathing or unable to speak, repeated as necessary; use basic life support (as above) if the patient becomes unconscious.

European Resuscitation Council Guidelines (2010). Resuscitation; 81: 1219–76

See also Advanced life support, adult; Cardiac arrest; Cardiopulmonary resuscitation, neonatal; Cardiopulmonary resuscitation, paediatric; International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation; Resuscitation Council (UK)

Batson’s plexus. Valveless epidural venous plexus composed of anterior and posterior longitudinal veins, communicating at each vertebral level with venous rings that pass transversely around the dural sac. Also communicates with basivertebral veins passing from the middle of the posterior surface of each vertebral body, and with sacral, lumbar, thoracic and cervical veins. It thus connects pelvic veins with intracranial veins. Provides an alternative route for venous blood to reach the heart from the legs. Originally described to explain a route for metastatic spread of tumours. Distends when vena caval venous return is obstructed, e.g. in pregnancy, thus reducing the space available for local anaesthetic solution in epidural anaesthesia.

Beclometasone dipropionate (Beclomethasone). Inhaled corticosteroid, used to prevent bronchospasm in asthma by reducing airway inflammation.

Becquerel. SI unit of radioactivity. One becquerel = amount of radioactivity produced when one nucleus disintegrates per second.

Bed sores, see Decubitus ulcers

Bee stings, see Bites and stings

Beer–Lambert law. Combination of two laws describing absorption of monochromatic light by a transparent substance through which it passes:

Forms the basis for spectrophotometric techniques, e.g. enzyme assays, oximetry, near infrared spectroscopy.

[August Beer (1825–1863) and Johann Lambert (1728–1777), German physicists]

Bell–Magendie law. The dorsal roots of the spinal cord are sensory, the ventral roots motor.

[Sir Charles Bell (1774–1842), Scottish surgeon; François Magendie (1783–1855), French physiologist]

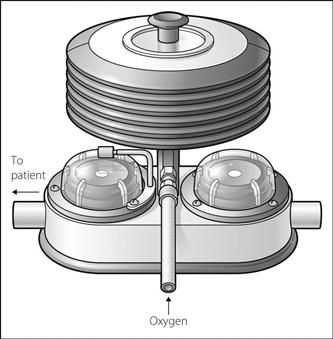

Bellows. Expansible container used to deliver controlled volumes of pressurised gas. May describe bellows incorporated into ventilators or hand-operated devices. The latter have been used in CPR and animal experiments for several centuries. More modern devices allow manual-controlled ventilation, and are either applied directly to the patient’s face or used in draw-over techniques.

Cardiff bellows: mainly used for resuscitation (rarely used now, self-inflating bags being preferred). Design:

Cardiff bellows: mainly used for resuscitation (rarely used now, self-inflating bags being preferred). Design:

– concertina bellows with a facemask at one end.

– non-rebreathing valve between the bellows and facemask.

Oxford bellows (Fig. 23): used for resuscitation or draw-over anaesthesia. Design:

Oxford bellows (Fig. 23): used for resuscitation or draw-over anaesthesia. Design:

– concertina bellows mounted on a block containing one-way valves.

In earlier models, an O2 inlet opened directly into the closed bellows system. This could allow build-up of excessive pressure, with risk of barotrauma.

Fig. 23 Oxford bellows

Bends, see Decompression sickness

Benzatropine mesylate (Benztropine). Anticholinergic drug, used to treat acute dystonic reactions and parkinsonism, especially drug-induced.

Benzodiazepine poisoning. Commonest overdose involving prescription drugs. Generally considered to be less serious than overdose with other sedatives, although death may occur, usually due to respiratory depression and aspiration of gastric contents. Of the benzodiazepines, temazepam is most sedating, and oxazepam least sedating, when taken in overdose. Often accompanied by alcohol poisoning.

Features are mainly those of CNS depression; hypoventilation and hypotension may also be present. Treatment is largely supportive. Flumazenil may be used but large doses may be required and the effects may be temporary; acute withdrawal and convulsions may be provoked in patients on chronic benzodiazepine therapy, those with alcohol dependence, or in cases of mixed drug overdoses (tricyclic antidepressants drug poisoning in particular).

Benzodiazepines. Group of drugs with sedative, anxiolytic and anticonvulsant properties. Also cause amnesia and muscle relaxation. Bind to the α and γ subunits of the GABAA receptor complex, potentiating the increase in chloride ion conductance caused by endogenous GABA. They thus enhance GABA-mediated inhibition in the brain and spinal cord, especially the limbic system and ascending reticular activating system.

premedication, e.g. diazepam, temazepam, lorazepam.

premedication, e.g. diazepam, temazepam, lorazepam.

sedation, e.g. diazepam, midazolam.

sedation, e.g. diazepam, midazolam.

as anticonvulsant drugs, e.g. diazepam, lorazepam, clonazepam.

as anticonvulsant drugs, e.g. diazepam, lorazepam, clonazepam.

induction of anaesthesia, e.g. midazolam.

induction of anaesthesia, e.g. midazolam.

Metabolism often produces active products with long half-lives that depend upon renal excretion, e.g. diazepam to temazepam and nordiazepam (the latter has a half-life of up to 900 h and is itself metabolised to oxazepam). In chronic use, benzodiazepines have largely replaced barbiturates as hypnotics and anxiolytics, since they cause fewer and less serious side effects. Overdosage is also less dangerous, usually requiring supportive treatment only. Hepatic enzyme induction is rare. A chronic dependence state may occur, with withdrawal featuring tremor, anxiety and confusion. Flumazenil is a specific benzodiazepine antagonist.

See also, γ-Aminobutyric acid receptors; Benzodiazepine poisoning

Benztropine, see Benzatropine

Benzylpenicillin (Penicillin G). Antibacterial drug, the first penicillin. Used mainly in infections caused by Gram-positive and -negative cocci, although its use is hampered by increasing bacterial resistance. The drug of choice in meningococcal disease, gas gangrene, tetanus, anthrax and diphtheria. Inactivated by gastric acid, thus poorly absorbed orally.

Bernard, Claude (1813–1878). French physiologist, whose many contributions to modern physiology include: demonstrating hepatic gluconeogenesis; proving that pancreatic secretions could digest food; discovering vasomotor nerves; and investigating the effects of curare at the neuromuscular junction. Also suggested the concept of the ‘internal environment’ (milieu intérieur) and homeostasis.

Bernoulli effect. Reduction of pressure when a fluid accelerates through a constriction. As velocity increases during passage through the constriction, kinetic energy increases. Total energy must remain the same, therefore potential energy (hence pressure) falls. Beyond the constriction, the pressure rises again. A second fluid may be entrained through a side arm into the area of lower pressure, causing mixing of the two fluids (Venturi principle).

Bert effect. Convulsions caused by acute O2 toxicity, seen with hyperbaric O2 therapy (3 atm).

Bezold–Jarisch reflex. Bradycardia, vasodilatation and hypotension following stimulation of ventricular receptors by ischaemia or drugs, e.g. nicotine and veratridine. Thought to involve inhibition of the baroreceptor reflex. Although of disputed clinical significance, a role in regulation of BP and the response to hypovolaemia has been suggested. The reflex may be activated during myocardial ischaemia or MI, and in rare cases of unexplained cardiovascular collapse following spinal/epidural anaesthesia.

Bicarbonate. Anion present in plasma at a concentration of 24–33 mmol/l, formed from dissociation of carbonic acid. Intimately involved with acid–base balance, as part of the major plasma buffer system. Filtered in the kidneys and reabsorbed to a variable extent, according to acid–base status. 80% of filtered bicarbonate is reabsorbed in the proximal tubule via formation of carbonic acid, which in turn forms CO2 and water aided by carbonic anhydrase. The bicarbonate ion itself does not pass easily across cell membranes.

increased blood pH shifts the oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve to the left, with increased affinity of haemoglobin for O2 and impaired O2 delivery to the tissues.

increased blood pH shifts the oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve to the left, with increased affinity of haemoglobin for O2 and impaired O2 delivery to the tissues.

severe tissue necrosis may follow extravasation.

severe tissue necrosis may follow extravasation.

For these reasons, treatment is usually reserved for pH below 7.1–7.2.

• Dose:

Presented as 8.4%, 4.2% and 1.26% solutions (1000 mmol/l, 500 mmol/l and 150 mmol/l respectively).

Bier, Karl August Gustav (1861–1949). Renowned German surgeon, Professor in Bonn and then Berlin. Introduced spinal anaesthesia using cocaine, describing its use on himself, his assistant and a series of patients, in 1899. Gave a classic description of the post-dural puncture headache he later suffered, and suggested CSF leakage during/after the injection as a possible cause. Also introduced IVRA, using procaine, in 1908. As consulting surgeon during World War I, he introduced the German steel helmet.

van Zundert A, Goerig M (2000). Reg Anesth Pain Med; 25: 26–33

Bier’s block, see Intravenous regional anaesthesia

Bigelow, Henry Jacob (1818–1890). US surgeon at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, he sponsored Wells’ abortive attempt at anaesthesia in 1845 and promoted and published the first account of Morton’s use of diethyl ether anaesthesia for surgery in 1846. Described several operations and the intraoperative events that occurred during them. Later, as a Professor, he became renowned for many contributions to surgery, including inventing a urological evacuator.

Biguanides. Hypoglycaemic drugs, used to treat non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Act by decreasing gluconeogenesis and by increasing glucose utilisation peripherally. Require some pancreatic islet cell function to be effective. May cause lactic acidosis, especially in renal or hepatic impairment. Lactic acidosis is particularly likely with phenformin, which is now unavailable in the UK. Metformin, the remaining biguanide, is used as first-line treatment in obese patients in whom diet alone is unsuccessful, or when a sulphonylurea alone is inadequate.

Biliary tract. Bile produced by the liver passes to the right and left hepatic ducts, which unite to form the common hepatic duct. This is joined by the cystic duct, which drains the gallbladder, to form the common bile duct; the latter drains into the duodenum (with the pancreatic duct) through the ampulla of Vater, the lumen of which is controlled by the sphincter of Oddi. Both infection of the biliary tree (cholangitis) and inflammation of the gallbladder (cholecystitis) may occur during critical illness.

Binding of drugs, see Pharmacokinetics; Protein-binding

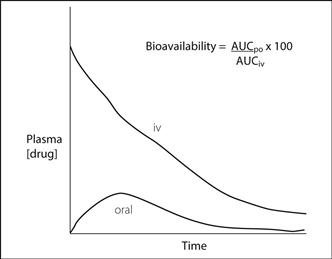

Bioavailability. Fraction of an administered dose of a drug that reaches the systemic circulation unchanged; iv injection thus provides 100% bioavailability. For an orally administered dose, it equals the area under the resultant concentration-against-time curve divided by that for an iv dose (Fig. 24). Low values of bioavailability occur with poorly absorbed oral drugs, or those that undergo extensive first-pass metabolism. Various formulations of the same drug may have different bioavailability. ‘Bioinequivalence’ is a statistically significant difference in bioavailability, whereas ‘therapeutic inequivalence’ is a clinically important difference, e.g. as may occur with different preparations of digoxin.

Fig. 24 Bioavailability

Biofeedback. Technique whereby bodily processes normally under involuntary control, e.g. heart rate, are displayed to the subject, enabling voluntary control to be learnt. Has been used to aid relaxation, and in chronic pain management when increased muscle tension is present, using the EMG as the displayed signal.

Bioimpedance cardiac output measurement, see Impedance plethysmography

an unusual clustering of illness in time or space.

an unusual clustering of illness in time or space.

an unusual age distribution of a common illness (e.g. apparent chickenpox in adults).

an unusual age distribution of a common illness (e.g. apparent chickenpox in adults).

disease that is more severe than expected.

disease that is more severe than expected.

disease outside its normal transmission season.

disease outside its normal transmission season.

multiple simultaneous epidemics of different diseases.

multiple simultaneous epidemics of different diseases.

unusual strains or variants of organisms or antimicrobial resistance patterns.

unusual strains or variants of organisms or antimicrobial resistance patterns.

botulism: a paralytic illness characterised by symmetric, descending flaccid paralysis of motor and autonomic nerves, usually beginning with the cranial nerves. Mortality is approximately 6% if appropriately treated.

botulism: a paralytic illness characterised by symmetric, descending flaccid paralysis of motor and autonomic nerves, usually beginning with the cranial nerves. Mortality is approximately 6% if appropriately treated.

Biotransformation, see Pharmacokinetics

Bispectral index monitor. Cerebral function monitor that uses a processed EEG obtained from a single frontal electrode to provide a measure of cerebral activity. Used to monitor anaesthetic depth in an attempt to prevent awareness. Produces a dimensionless number (the BIS number) ranging from 100 (fully awake) to 0 (no cerebral activity). The algorithm used to calculate the BIS value is commercially protected but is based on power spectral analysis of the EEG, the synchrony of slow and fast wave activity and the burst suppression ratio. Targeting a BIS number of 40–60 is advocated to reduce awareness and allow more rapid emergence from anaesthesia, although the evidence does not support its routine use.

Bisphosphonates. Group of drugs that inhibit osteoclast activity; used in Paget’s disease, osteoporosis, metastatic bone disease and hypercalcaemia. They are adsorbed on to hydroxyapatite crystals, interfering with bone turnover and thus slowing the rate of calcium mobilisation. May be given orally or by slow iv infusion, e.g. in severe hypercalcaemia of malignancy:

ibandronic acid: 2–4 mg by a single infusion.

ibandronic acid: 2–4 mg by a single infusion.

sodium clodronate: 300 mg/day for 7–10 days or 1.5 g by a single infusion.

sodium clodronate: 300 mg/day for 7–10 days or 1.5 g by a single infusion.

zoledronic acid: 4–5 mg (depending on the preparation) over 15 min by a single infusion.

zoledronic acid: 4–5 mg (depending on the preparation) over 15 min by a single infusion.

Side effects include hypocalcaemia, hypophosphataemia, pyrexia, flu-like illness, vomiting and headache. Blood dyscrasias, hyper- or hypotension, renal and hepatic dysfunction may rarely occur, especially with disodium pamidronate. Osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femoral fractures have also been reported, mainly associated with long-term administration.

Bites and stings. May include animal bites, and animal or plant stings. Problems are related to:

local tissue trauma itself: damage to vital organs, haemorrhage, oedema. Importance varies with the size, location and number of the wound(s).

local tissue trauma itself: damage to vital organs, haemorrhage, oedema. Importance varies with the size, location and number of the wound(s).

– respiratory: bronchospasm, pulmonary oedema, respiratory failure (type I or II), airway obstruction (from oedema).

– cardiovascular: hypertension (from neurotransmitter release), hypotension (from cardiac depression, hypovolaemia, vasodilatation), arrhythmias.

– neurological: confusion, coma, convulsions.

– neuromuscular: cranial nerve palsies and peripheral paralysis (from pre- or postsynaptic neuromuscular junction blockade), muscle spasms (from neurotransmitter release), rhabdomyolysis.

– gastrointestinal: nausea, vomiting.

– haematological: coagulation disorders, haemolysis.

– renal: impairment from myoglobinuria, hypotension and direct nephrotoxicity.

wound infection, either introduced at the time of injury or acquired secondarily.

wound infection, either introduced at the time of injury or acquired secondarily.

initial resuscitation as for trauma, anaphylaxis. Rapid transfer of victims of envenomation to hospital is the most important prehospital measure. Jewellery should be removed from the affected limb as swelling may be marked.

initial resuscitation as for trauma, anaphylaxis. Rapid transfer of victims of envenomation to hospital is the most important prehospital measure. Jewellery should be removed from the affected limb as swelling may be marked.

general supportive management according to the system affected. IV fluids are usually required. Blood should be taken early as certain venoms and antivenoms may interfere with grouping. Frequent assessment of all systems and degree of swelling are important. Antitetanus immunisation should be given. Broad-spectrum antibacterial drugs are often given.

general supportive management according to the system affected. IV fluids are usually required. Blood should be taken early as certain venoms and antivenoms may interfere with grouping. Frequent assessment of all systems and degree of swelling are important. Antitetanus immunisation should be given. Broad-spectrum antibacterial drugs are often given.

Singletary EM, Rochman AS, Bodmer JC, Holstege CP (2005). Med Clin North Am; 89: 1195–224

Bivalirudin. Recombinant hirudin used as anticoagulant in acute coronary syndromes.

• Dosage:

in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), including those with S-T segment elevation MI: 750 µg/kg iv initially followed by 1.75 mg/kg/h for up to 4 h after procedure.

in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), including those with S-T segment elevation MI: 750 µg/kg iv initially followed by 1.75 mg/kg/h for up to 4 h after procedure.

Bladder washouts. Main types used in ICU:

to remove debris and exclude catheter blockage as a cause of oliguria: sterile saline. Various solutions are available to remove phosphate deposits.

to remove debris and exclude catheter blockage as a cause of oliguria: sterile saline. Various solutions are available to remove phosphate deposits.

for urinary tract infection: chlorhexidine 1 : 5000 (may cause burning and haemorrhage); ineffective in pseudomonal infections. Saline may also be used. Amphotericin may be used in fungal infection.

for urinary tract infection: chlorhexidine 1 : 5000 (may cause burning and haemorrhage); ineffective in pseudomonal infections. Saline may also be used. Amphotericin may be used in fungal infection.

Blast injury, see Chest trauma

Bleeding time, see Coagulation studies

Bleomycin. Antibacterial cytotoxic drug, given iv or im to treat lymphomas and certain other solid tumours. Side effects include alveolitis, dose-dependent progressive pulmonary fibrosis, skin and allergic reactions (common) and myelosuppression (rare). Pulmonary fibrosis is thought to be exacerbated if high concentrations of O2 are administered, e.g. for anaesthesia. Suspicion of fibrosis (CXR changes or basal crepitations) is an indication to stop therapy.

Blood, artificial. Synthetic solutions capable of O2 transport and delivery to the tissues. Circumvent many of the complications of blood transfusion and avoid the need for blood compatibility testing. Two types have been investigated:

haemoglobin solutions:

haemoglobin solutions:

– the oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve of free haemoglobin is markedly shifted to the left of that for intraerythrocyte haemoglobin, reducing its usefulness.

– must be stored in O2-free atmosphere to avoid oxidisation to methaemoglobin.

Various modifications of the haemoglobin molecule have been made in order to prolong its half-life from under 1 h to over 24 h, including polymerisation with glutaraldehyde, linking haemoglobin with hydroxyethyl starch or dextran, cross-linking the α or β chains, and fusing the chains end to end (the latter has been done with recombinant human haemoglobin). Bovine haemoglobin, and encapsulation of haemoglobin within liposomes, has also been used. Many of these preparations are currently undergoing clinical trials.

perfluorocarbon solutions (e.g. Fluosol DA20) carry dissolved O2 in an amount directly proportional to its partial pressure, and have been used to supplement O2 delivery in organ ischaemia due to shock, arterial (including coronary) insufficiency and haemorrhage. Have been used for liquid ventilation. Even with high FIO2, O2 content is less than that of haemoglobin (newer compounds may be more efficient at O2 carriage). Accumulation in the reticuloendothelial system is of unknown significance. Clinical trials are continuing.

perfluorocarbon solutions (e.g. Fluosol DA20) carry dissolved O2 in an amount directly proportional to its partial pressure, and have been used to supplement O2 delivery in organ ischaemia due to shock, arterial (including coronary) insufficiency and haemorrhage. Have been used for liquid ventilation. Even with high FIO2, O2 content is less than that of haemoglobin (newer compounds may be more efficient at O2 carriage). Accumulation in the reticuloendothelial system is of unknown significance. Clinical trials are continuing.

Blood–brain barrier. Physiological boundary between the bloodstream and CNS, preventing transfer of hydrophilic substances from plasma to brain. The original concept was suggested by the lack of staining of brain tissue by aniline dyes given systemically. Passage of hydrophilic molecules is impeded by tight junctions between capillary endothelial cells in the brain and epithelial cells in the choroid plexus; glial cells also contribute. Active transport may still occur for specific molecules, e.g. glucose. Certain areas of the brain lie outside the barrier, e.g. the hypothalamus and areas lining the third and fourth ventricles (including the chemoreceptor trigger zone).

In the absence of active transport, the ability of chemicals to cross the barrier is proportional to their lipid solubility, and inversely proportional to molecular size and charge. Water, O2 and CO2 cross freely; charged ions and larger molecules take longer to cross, unless lipid-soluble. All substances eventually penetrate the brain; the rate of penetration is important clinically. Some drugs only cross the barrier in their unionised, non-protein-bound form, i.e. a small proportion of the injected dose, e.g. thiopental. Quaternary amines, such as neuromuscular blocking drugs and glycopyrronium, are permanently charged, and cross to a very limited extent (cf. atropine).

The effectiveness of the barrier is reduced in neonates compared with adults: hence the increased passage of drugs (e.g. opioid analgesic drugs) and other substances (e.g. bile salts, causing kernicterus). Localised pathology, e.g. trauma, malignancy and infection, may also reduce the integrity of the barrier.

Blood compatibility testing. Procedures performed on donor and recipient blood before blood transfusion, to determine compatibility. Necessary to avoid reactions caused by transfusion of red cells into a recipient whose plasma contains antibodies against them. ABO and Rhesus are the most relevant blood group systems clinically, although others may be important.

• Methods:

Blood cultures. Microbiological culture of blood, performed to detect circulating micro-organisms. Blood is taken under aseptic conditions and injected into (usually two) bottles containing culture medium, for aerobic and anaerobic incubation. Diluting the sample at least 4–5 times in the culture broth reduces the antimicrobial activity of serum and of any circulating drugs. Changing the hypodermic needle between taking blood and injection into the bottles is not now thought to be necessary, although contamination of the needle and bottles must be avoided. Sensitivity depends on the type of infection, the number of cultures and volume of blood taken. At least 2–3 cultures, each using at least 10–30 ml blood, are usually recommended. More samples may be required when there is concurrent antibacterial drug therapy (the sample may be diluted several times or the drug removed in the laboratory to increase the yield) or when endocarditis is suspected. False-positive results may be suggested by the organism recovered (e.g. bacillus species, coagulase-negative staphylococci, diphtheroids) and their presence in only a single culture out of many and after prolonged incubation.

Blood filters. Devices for removing microaggregates during blood transfusion. Platelet microaggregates form early in stored blood, with leucocytes and fibrin aggregates occurring after 7 days’ storage. Pulmonary microembolism has been suggested as a cause of pulmonary dysfunction following transfusion.

Standard iv giving sets suitable for blood transfusion contain screen filters of 170 µm pore size. Filtration of microaggregates requires microfilters of 20–40 µm pore size. The general use of microfilters is controversial; by activating complement in transfused blood they may increase formation of microaggregates within the recipient’s bloodstream. They add to expense, increase resistance to flow and may cause haemolysis. They have, however, been shown to be of use in extracorporeal circulation.

Leucodepletion filters are used in cell salvage, e.g. to remove cellular fragments, but their routine use has been questioned because of rare reports of severe hypotension in recipients, possibly related to release of bradykinin and/or other mediators when blood is passed over filters with a negative charge.

A filter capable of removing prion proteins that cause Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease is under evaluation.

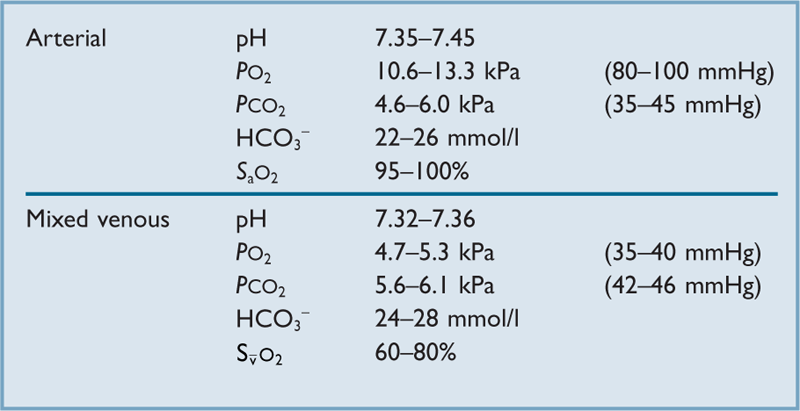

Blood flow. For any organ:

thus the haemodynamic correlate of Ohm’s law.

Perfusion pressure depends not only on arterial and venous pressures but also on local pressures within the capillary circulation.

vessel radius, controlled by humoral, neural and local mechanisms (autoregulation).

vessel radius, controlled by humoral, neural and local mechanisms (autoregulation).

blood viscosity. Reduced peripherally due to plasma skimming, which results in blood with reduced haematocrit leaving vessels via side branches. Reduced in anaemia.

blood viscosity. Reduced peripherally due to plasma skimming, which results in blood with reduced haematocrit leaving vessels via side branches. Reduced in anaemia.

Flow is normally laminar; i.e. it roughly obeys the Hagen–Poiseuille equation, although blood vessels are not rigid, arterial flow is pulsatile and blood is not an ideal fluid. Turbulent flow may occur in constricted arteries and in the hyperdynamic circulation, particularly in anaemia, when viscosity is reduced (see Reynolds’ number).

Blood/gas partition coefficients, see Partition coefficients

Blood gas analyser. Device used to measure blood gas tensions, pH, electrolytes, metabolites and haemoglobin derivatives. Incorporates a series of measuring electrodes ± a co-oximeter. Directly measured parameters include pH, PO2, PCO2. Bicarbonate, standard bicarbonate and base excess are derived. Inaccuracy may result from excess heparin (acidic), bubbles within the sample and metabolism by blood cells. The latter is reduced by rapid analysis after taking the sample, or storage of the sample on ice. O2, CO2 and pH electrodes require regular maintenance and two-point calibration.

See also Blood gas interpretation; Carbon dioxide measurement; Oxygen measurement; pH measurement

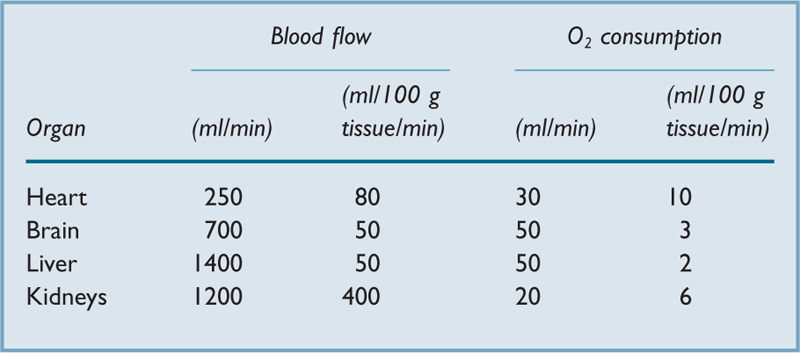

Blood gas interpretation. Normal ranges are shown in Table 10.

• Suggested plan for interpretation:

– knowledge of the FIO2 is required before interpretation is possible.

– calculation of the alveolar PO2 (from alveolar gas equation).

– calculation of the alveolar–arterial O2 difference.

– identification of acidaemia or alkalaemia, representing acidosis or alkalosis respectively.

– identification of a respiratory component by referring to the CO2 tension.

See also, Blood gas analyser; Carbon dioxide measurement; Carbon dioxide transport; Oxygen measurement; Oxygen transport; pH measurement

Blood groups. Each individual’s red cells bear certain antigens capable of producing an antibody response in another person. Some are only present on red cells, e.g. Rhesus antigens; others are also present on other tissue cells, e.g. ABO antigens. Immunoglobulins may be present intrinsically, e.g. ABO and Lewis, or following exposure to the antigen, e.g. Rhesus; they are usually IgG or IgM. Administration of blood cells to a recipient who has the corresponding antibody causes haemolysis and a severe reaction.

Minor blood groups may be important clinically following ABO-typed uncross-matched blood transfusion, or multiple transfusions; an atypical antibody in a recipient makes the finding of suitable donor blood difficult. Minor groups include the Kell, Duffy, Lewis and Kidd systems. Many more have been described; the significance of such diversity is unclear.

Blood loss, perioperative. Important as a guide to perioperative fluid requirements, and also as indicator of potential development of a coagulation disorder related to major haemorrhage.

clinical judgement of the patient’s volume status.

clinical judgement of the patient’s volume status.

observation of wound and swabs.

observation of wound and swabs.

Replacement with blood has been suggested if losses exceed 15–20% of blood volume in adults, or 10% in children, although greater losses may be allowed if the preoperative haemoglobin concentration is high. Recent guidelines suggest that, under stable conditions, a haemoglobin concentration of 7–10 g/dl should be a general indication for blood transfusion, depending on the circumstances. Until blood transfusion becomes necessary, losses may be replaced with colloid or crystalloid solutions (the latter in about 2–3 times the volume of the former).

• Blood loss may be reduced by:

local infiltration with vasopressor drugs.

local infiltration with vasopressor drugs.

appropriate positioning, e.g. head-up for ENT surgery.

appropriate positioning, e.g. head-up for ENT surgery.

spinal and epidural anaesthesia.

spinal and epidural anaesthesia.

• Bleeding may be increased by:

– raised intrathoracic pressure, e.g. due to respiratory obstruction, coughing, straining.

– fluid overload and cardiac failure.

– incompatible blood transfusion.

– DIC.

Blood patch, epidural. Procedure for the relief of post-dural puncture headache. 10–20 ml of the patient’s blood is drawn from a peripheral vein under sterile conditions, and injected immediately into the epidural space. Blood is thought to seal the dura, thus preventing further CSF leak, although cranial displacement of CSF resulting from epidural injection may also be important, at least initially. Maintaining the supine position for at least 2–4 h after patching is recommended to increase the chance of success, by reducing dislodgement of the clot from the dural puncture site. Should be avoided if the patient is febrile, in case of bacteraemia and subsequent epidural abscess. The sending of blood for culture at the time of patching has been suggested, in case infection does occur.

Blood pressure, see Arterial blood pressure; Diastolic blood pressure; Mean blood pressure; Systolic blood pressure

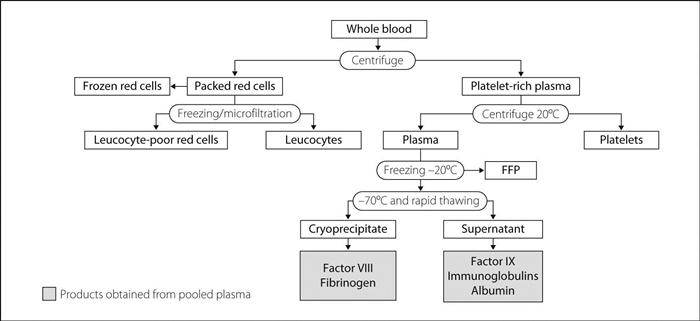

Blood products. Many products may be obtained from donated blood (Fig. 25), including:

whole blood: stored at 2–6°C for up to 35 days. 70 ml citrate preservative solution is added to 420 ml blood. The use of whole blood for blood transfusion is restricted in the UK. Heparinised whole blood (lasts for 2 days) has been used for paediatric cardiac surgery.

whole blood: stored at 2–6°C for up to 35 days. 70 ml citrate preservative solution is added to 420 ml blood. The use of whole blood for blood transfusion is restricted in the UK. Heparinised whole blood (lasts for 2 days) has been used for paediatric cardiac surgery.

packed red cells (plasma reduced): stored at 2–6°C for up to 35 days. Should be kept at room temperature for no more than 24 h. Haematocrit is approximately 0.55. Produced by removing all but 20 ml residual plasma from a unit of whole blood and suspending the cells in 100 ml SAG-M (saline–adenine–glucose–mannitol) solution to give a mean volume per unit of 280 ml. Since 1998, routinely depleted of leucocytes to decrease the risk of transmitting variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. One unit typically increases haemoglobin concentration in a 70-kg adult by 1 g/dl.

packed red cells (plasma reduced): stored at 2–6°C for up to 35 days. Should be kept at room temperature for no more than 24 h. Haematocrit is approximately 0.55. Produced by removing all but 20 ml residual plasma from a unit of whole blood and suspending the cells in 100 ml SAG-M (saline–adenine–glucose–mannitol) solution to give a mean volume per unit of 280 ml. Since 1998, routinely depleted of leucocytes to decrease the risk of transmitting variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. One unit typically increases haemoglobin concentration in a 70-kg adult by 1 g/dl.

platelets: stored at 22°C for up to 5 days. Obtained either from a single donor by plateletpheresis (one donation yielding 1–3 therapeutic dose units) or from multiple units of donated whole blood (one unit of platelets derived from four donors). Transfusion thresholds vary according to the clinical situation, the level of platelet function and laboratory evidence of coagulopathy, but typically include a platelet count of 50 × 109/l or less for surgery, unless platelet function is abnormal. One therapeutic dose unit (approximate volume 210–310 ml) normally increases the platelet count by 20–40 × 109/l, although some patients may exhibit ‘refractoriness’ (e.g. those with circulating antiplatelet antibodies). Filtered by microfilters; ordinary iv giving sets are suitable. Preferably should be ABO-compatible. Contains added citrate.

platelets: stored at 22°C for up to 5 days. Obtained either from a single donor by plateletpheresis (one donation yielding 1–3 therapeutic dose units) or from multiple units of donated whole blood (one unit of platelets derived from four donors). Transfusion thresholds vary according to the clinical situation, the level of platelet function and laboratory evidence of coagulopathy, but typically include a platelet count of 50 × 109/l or less for surgery, unless platelet function is abnormal. One therapeutic dose unit (approximate volume 210–310 ml) normally increases the platelet count by 20–40 × 109/l, although some patients may exhibit ‘refractoriness’ (e.g. those with circulating antiplatelet antibodies). Filtered by microfilters; ordinary iv giving sets are suitable. Preferably should be ABO-compatible. Contains added citrate.

fresh frozen plasma (FFP): stored at −30°C for up to 2 years. Must be ABO-compatible. Once thawed, can be stored at 4°C and must be given within 24 h, or kept at room temperature and given within 4 h. Contains all clotting factors, including fibrinogen, and is also a source of plasma cholinesterase. Contains added citrate. Viral infection risk is as for whole blood. In the UK, one unit of FFP is derived from plasma from a single donor, and FFP for children born after 1995 is derived from unpaid US donors. Indicated for treatment of various coagulopathies e.g. multifactor deficiencies associated with major haemorrhage and/or DIC. One adult therapeutic dose is 12–15 ml/kg or 4 units for a 70-kg adult, and would typically increase the fibrinogen concentration by 1 g/l.

fresh frozen plasma (FFP): stored at −30°C for up to 2 years. Must be ABO-compatible. Once thawed, can be stored at 4°C and must be given within 24 h, or kept at room temperature and given within 4 h. Contains all clotting factors, including fibrinogen, and is also a source of plasma cholinesterase. Contains added citrate. Viral infection risk is as for whole blood. In the UK, one unit of FFP is derived from plasma from a single donor, and FFP for children born after 1995 is derived from unpaid US donors. Indicated for treatment of various coagulopathies e.g. multifactor deficiencies associated with major haemorrhage and/or DIC. One adult therapeutic dose is 12–15 ml/kg or 4 units for a 70-kg adult, and would typically increase the fibrinogen concentration by 1 g/l.

human albumin solution (HAS; previously called plasma protein fraction, PPF): stored at room temperature for 2–5 years depending on the preparation. Heat-treated to kill viruses. Contains virtually no clotting factors. Available as 4.5% and 20% (salt-poor albumin) solutions; both contain 140–150 mmol/l sodium but the latter contains less sodium per gram of albumin. Licensed for blood volume expansion with or without hypoalbuminaemia. Use is controversial owing to its high cost and the absence of evidence demonstrating its superiority to other colloids. UK supplies are now sourced from the USA.

human albumin solution (HAS; previously called plasma protein fraction, PPF): stored at room temperature for 2–5 years depending on the preparation. Heat-treated to kill viruses. Contains virtually no clotting factors. Available as 4.5% and 20% (salt-poor albumin) solutions; both contain 140–150 mmol/l sodium but the latter contains less sodium per gram of albumin. Licensed for blood volume expansion with or without hypoalbuminaemia. Use is controversial owing to its high cost and the absence of evidence demonstrating its superiority to other colloids. UK supplies are now sourced from the USA.

factor concentrates, e.g. VIII and IX: now obtained by recombinant gene engineering, removing the risk of viral infection. Recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa) is licensed for the treatment of patients with acquired or congenital haemophilia, von Willebrand’s disease and inhibitors to factors VIII or IX of the clotting cascade. Factor VIIa enhances thrombin generation on the surfaces of activated platelets, thus having a mainly local effect with little impact on systemic coagulation. Increasingly used off-licence for arresting major traumatic, surgical and obstetric haemorrhage, although use is restricted owing to extremely high cost.

factor concentrates, e.g. VIII and IX: now obtained by recombinant gene engineering, removing the risk of viral infection. Recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa) is licensed for the treatment of patients with acquired or congenital haemophilia, von Willebrand’s disease and inhibitors to factors VIII or IX of the clotting cascade. Factor VIIa enhances thrombin generation on the surfaces of activated platelets, thus having a mainly local effect with little impact on systemic coagulation. Increasingly used off-licence for arresting major traumatic, surgical and obstetric haemorrhage, although use is restricted owing to extremely high cost.