Chapter 8 Axillary Nerve

Anatomy

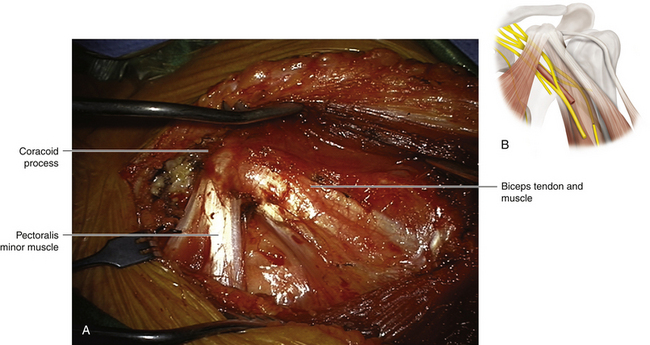

• The coracoid process of the scapula is a key landmark in axillary nerve dissection. It is palpable throughout every stage of the operation (Figure 8-1).

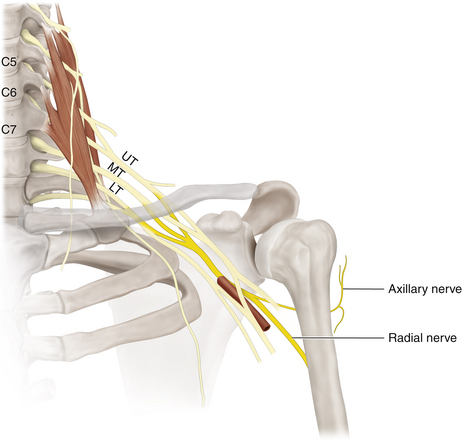

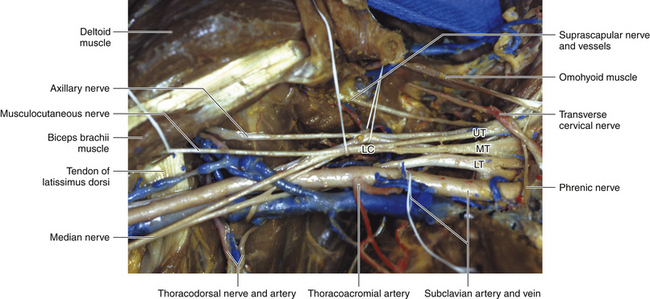

• The glenoid articular surface of the scapula is relatively small compared with the articular surface of the humerus. The integrity of the shoulder joint is much dependent on large and small muscles and their nerve supply. The spinal nerves exit the plane between the scalenus anterior and scalenus medius, and their fibers traverse the trunks, divisions, and cords to reach the named nerves that supply the muscles (Figures 8-2 and 8-3).

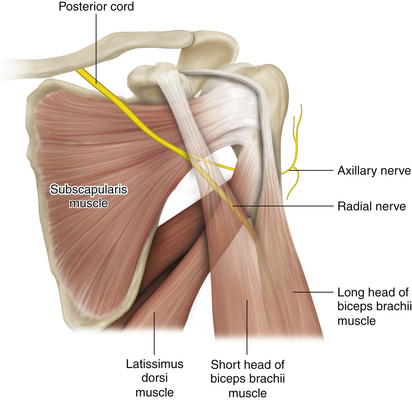

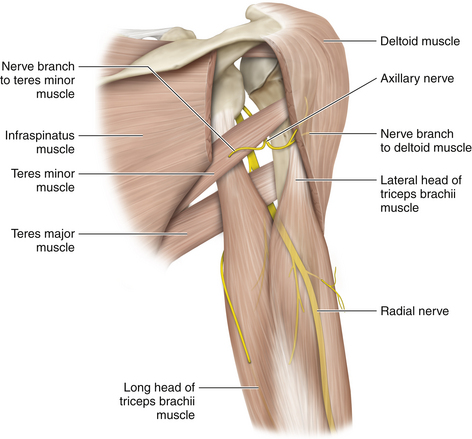

• The costal, concave surface of the scapula is covered by the subscapularis, which in turn is covered by thick fascia (Figure 8-4). The dorsal surface is covered by the supraspinatus and infraspinatus. The latter is crucial for external rotation of the humerus (Figure 8-5). Even if shoulder abduction and elbow flexion are restored after surgery, in the absence of external rotation the patient will have difficulty bringing food to the mouth.

• The origin of the teres major from the lateral side of the inferior angle of the scapula and the insertion of that muscle below the subscapularis into the humerus should be studied. The deltoid suspends the humerus at the shoulder joint, pulling it upward, and the teres major has the reverse action. Paralysis of the deltoid thins the muscle to reveal that the head of the humerus is being pulled down by the teres major and gravity.

• The origin of the deltoid, from the clavicle and the acromion and spine of the scapula, should be reviewed. The anterior origin does not impede the surgeon’s view of the brachial plexus, but the origin of the posterior deltoid may occasionally need partial division to make it easier to see the axillary nerve from the posterior approach. The deltoid is inserted into the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus. (This is a useful level at which to study the cross-sectional anatomy of the arm, because many relationship changes occur at this level: the median nerve in its relationship to the brachial artery, the ulnar nerve to the medial intermuscular septum, and the radial nerve to the humerus.)

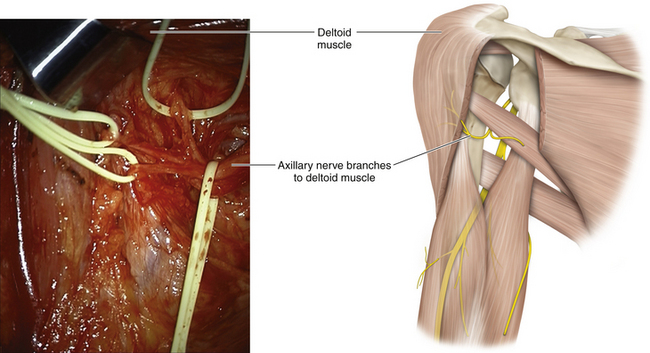

• The fibers of the deltoid are bunched into anterior, lateral, and posterior components. These three segments should be observed individually in cases of deltoid paralysis and in reinnervation following axillary nerve repair (Figure 8-6). The skin over the deltoid is supplied by C5 fibers, by way of the axillary and superior lateral brachial cutaneous nerves.

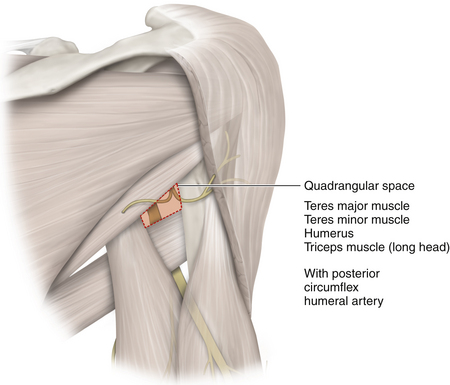

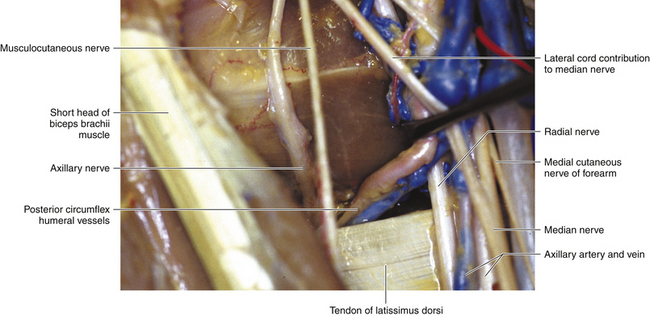

• The massive latissimus dorsi narrows to a shiny tendon of insertion, which winds around the inferior border of teres major en route to its insertion in the humerus. The quadrilateral space is bounded by the subscapularis above and the teres major below, but the surgeon uses the upper border of the thin, shiny tendon of latissimus dorsi, winding around teres major, as the guide to the space (Figure 8-7; see also Figure 8-3).

• The three muscles of the posterior wall of the axilla are all supplied by the posterior cord (subscapular nerve, nerve to latissimus dorsi, and nerve to teres major). When operating from the front, however, the fascia over the subscapularis and the tendon of latissimus dorsi form the background to the plexus.

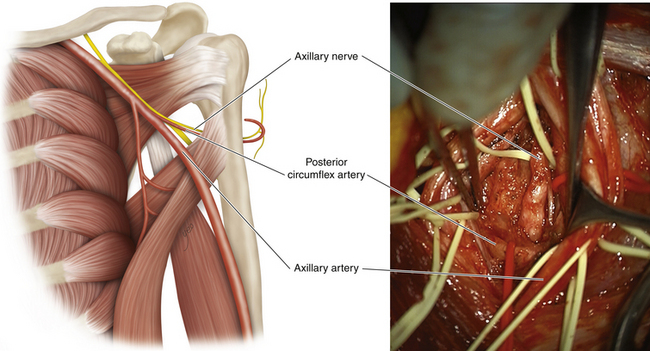

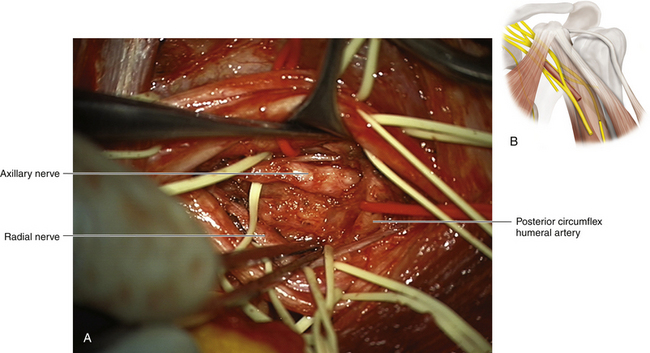

• Passing a fingertip above the upper border of the latissimus dorsi tendon leads the surgeon into the quadrangular space. Gentle tenting of the axillary artery will put tension on the posterior circumflex artery (which is of variable size). This vessel also leads to the quadrangular space and the identification of the axillary nerve (Figures 8-8 and 8-9).

• The axillary nerve departs from the radial nerve at the termination of the posterior cord and curls over the inferior edge of subscapularis to gain the quadrangular space. It runs around the surgical neck of the humerus, below the capsule of the shoulder joint.

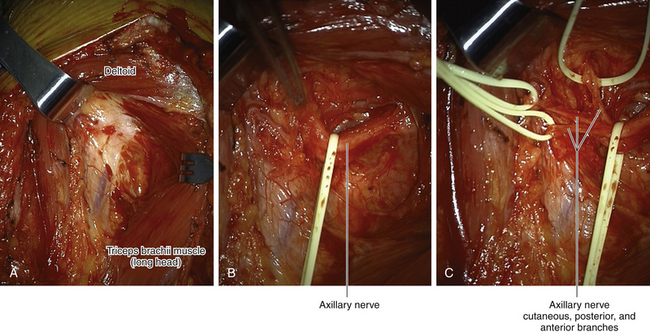

• When viewed from behind, the nerve emerges below the teres minor, between the separated long and lateral heads of the triceps muscle. At this stage, having given off the nerve supplying the teres minor, it may continue as two or three branches before gaining the undersurface of the deltoid muscle.

Technique

• Following the standard approach to the infraclavicular plexus, the surgeon dissects out the musculocutaneous nerve. The fascicles destined to supply this nerve are then separated from the lateral cord for ½ to 1 inch, without injuring either component. This step slackens the musculocutaneous nerve and improves visualization of the axillary nerve at a later phase of the operation, without damage to the musculocutaneous nerve.

• The surgeon must be particularly careful not to engage the mobilized musculocutaneous nerve in the teeth of self-retaining retractors while attention is being focused for some time on the axillary nerve in the depths of the wound. It is distressing for the patient and embarrassing for the surgeon to observe weak elbow flexion following surgery, added to the preexisting paralyzed shoulder abduction (Figure 8-10).

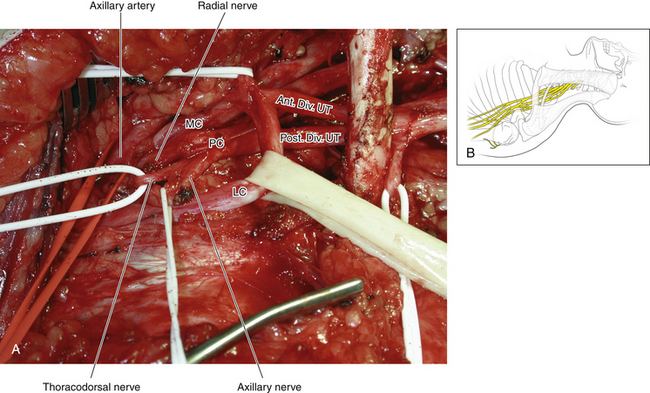

• The posterior cord is dissected by operating alternately both medial to and lateral to the axillary artery. The coracoid process is a constant landmark and guides the surgeon to the level of the takeoff of the axillary nerve from the posterior cord.

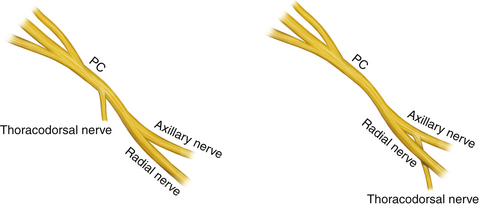

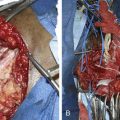

• The nerve to latissimus dorsi should be identified, because its point of origin is variable; this nerve should be protected while operating on the proximal axillary nerve (Figures 8-11 and 8-12).

• Every effort should be made to retain continuity of the damaged axillary nerve as the surgeon operates down into the quadrangular space, with the hope of finding viable distal nerve.

• If necessary, a separate incision is made over the posterior border of the deltoid (Figure 8-13). After the long and lateral heads of the triceps are separated, the axillary nerve will be seen issuing below the teres minor as one, two, or three branches. Grafts can be led from the axilla, through the quadrangular space, to these branches. This is usually a clean approach, because the scarring attending an axillary nerve injury is frequently (but not invariably) confined to the axilla.

• In the dissection laboratory, the display of the axillary nerve is straightforward. Scarring resulting from stretch injury or prior shoulder surgery, however, makes this operation significantly more difficult. The operating microscope may be used to provide bright illumination at the back of the axilla, for the benefit of both the surgeon and the assistant, so that fine sutures may be accurately placed into the fascicles of the distal stump. It is essential that the distal suture line be at a point where there are viable fascicles in the distal stump. There is no point in suturing grafts to wisps of fibrous tissue. Similarly, the proximal stump must be trimmed back, if necessary separating fascicles away from the posterior cord, until viable fascicles are found (with care taken to preserve the nerve to latissimus dorsi).

• The posterior incision should be marked out and access to it ensured before the drapes are applied. In most cases, an experienced surgeon can lead a graft from a viable proximal stump to a suitable distal stump in the quadrangular space from the anterior approach alone. If the surgeon decides to add the posterior approach, however, it is a significant nuisance not to have drawn out the incision and prepared and draped the posterior area before beginning the anterior approach.