CHAPTER 19 Axillary block

Clinical anatomy

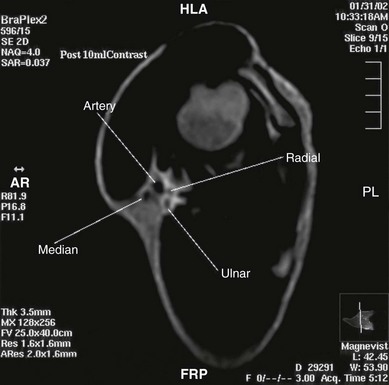

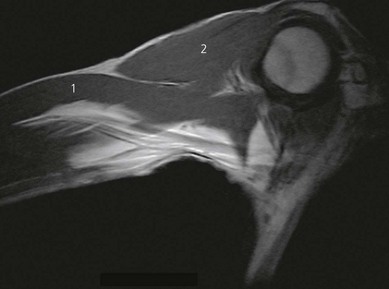

At the site of axillary block the terminal nerves of the brachial plexus form a particular pattern with the axillary artery (Fig. 19.1). Around the second part of the artery – the divisions being produced by the pectoralis minor muscle – the median nerve lies anteriorly, the radial nerve posteriorly, and the ulnar nerve posteromedially (Fig. 19.2). The axillary vein lies more medial. The musculocutaneous nerve has left the fascial sheath at the level of the coracoid and is thus unlikely to be anesthetized with single-injection axillary technique. The medial cutaneous nerve of arm and the intercostobrachial nerve lie subcutaneously.

Sonoanatomy

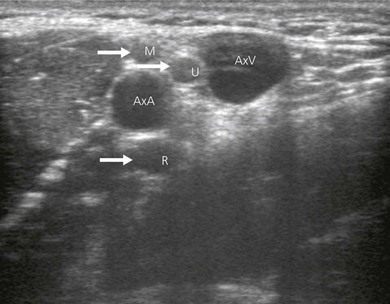

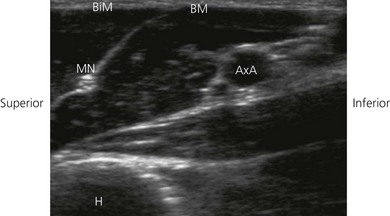

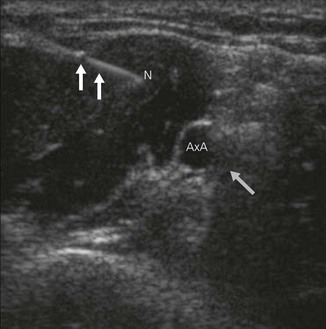

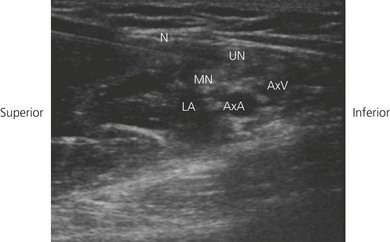

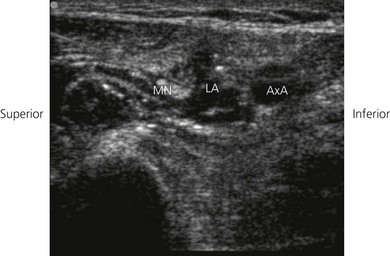

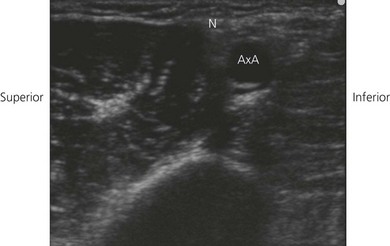

In ultrasound scanning of the axillary brachial plexus, the patient is positioned supine with the arm abducted 90° on an arm board. A linear 6–13 MHz ultrasound transducer is used. Begin the examination by scanning the upper arm in the axilla just distal to the border of the pectoralis muscle. A transverse or short-axis view is used. Perform a systematic anatomical survey from superficial to deep and above and below the axillary artery. Identify the humerus and the triceps, biceps and coracobrachialis muscles. Identify the pulsatile axillary artery. Decrease transducer pressure to allow axillary veins to expand and be identified. The Doppler options facilitate identification of the vascular structures, thereby contributing to minimizing vascular puncture. The nerves lie in a close relationship to the axillary artery near the apex of the axilla, before they start diverging. There is considerable variation in their relationship to the artery and they are very mobile; slight pressure of the transducer can displace the nerves. The nerves appear as hypoechoic structures with a hyperechoic circumference (Fig. 19.3). By sliding the ultrasound transducer proximally towards the apex of the axilla, the musculocutanous nerve can be traced to its origin from the lateral cord (Fig. 19.4). Distally, it diverges from the axillary artery to travel in the coracobrachialis muscle. The axillary nerve also originates from the posterior cord and can be seen going cephalad towards the surgical neck of the humerus. By moving the ultrasound transducer distally, the radial nerve can be traced winding around the humerus.

Technique

Landmark-based approach

The patient lies supine with the arm abducted (80°) and the elbow flexed (90°; Fig. 19.5). Hyperabduction should be avoided because it can make palpation of the artery difficult and distort the distribution of local anesthetic. The axillary artery is palpated as far proximally as possible under the lateral edge of the pectoralis major muscle, and fixed with the index and middle fingers. A 35-mm 21-G insulated stimulating needle is used. The stimulating current is set at 1.0 mA, 2 Hz, and 0.1 ms. The needle is advanced proximally at an angle of 30° in the direction (Fig. 19.6) of the neurovascular sheath. Entry of the needle into the neurovascular sheath is confirmed by a ‘fascial click’. The needle is advanced slowly until the appropriate muscle response is obtained.

Stimulation of the median nerve produces flexion of the middle and index fingers, thumb, and pronation and flexion of the wrist. Stimulation of the ulnar nerve produces flexion of the ring and little fingers with ulnar deviation of the wrist, while stimulation of the radial nerve will produce dorsiflexion of the fingers and wrist. Finger flexion alone in the case of the ring and little fingers could represent either ulnar or median stimulation. The needle position is adjusted while decreasing the current to 0.30 mA with maintenance of the muscle response (Fig. 19.7). A muscle response in the upper arm should not be accepted. Individual nerves can be targeted and located with ease. Ideally, the nerve(s) supplying the area of surgery should be sought.

Incremental injection of the local anesthetic is made with repeated aspiration. To block terminal nerves of the plexus, 40 mL of local anesthetic is sufficient. If a multiple-injection technique is used, 10 mL at each site is adequate. The stimulating current needs to be increased for the second and subsequent nerves because the previously injected local anesthetic will increase the electrical resistance in the area. To increase the likelihood of blocking the musculocutaneous nerve, digital pressure is maintained distal to the site of injection to encourage proximal spread of the local anesthetic within the axillary sheath; a tourniquet may be used for a similar effect (Figs 19.8 and 19.9). The arm is then placed across the chest.

If an upper arm tourniquet is to be used, additional block of the intercostobrachial nerve and medial cutaneous nerve of the arm is of value to reduce the cutaneous element of the pain due to the tourniquet. The intercostobrachial nerve is the lateral cutaneous branch of the second intercostal nerve. The medial cutaneous nerve of the arm originates from the medial cord of the brachial plexus. Block of both nerves can be achieved with a subcutaneous injection of local anesthetic in the medial aspect of the upper arm (Fig. 19.10). Injection should be made from the biceps muscle to the triceps muscle.

Musculocutaneous nerve block

The musculocutaneous nerve can be blocked as part of an infraclavicular technique using the vertical infraclavicular or coracoid approaches (see Ch. 18). An injection into the body of the coracobrachialis will also anesthetize it without the need to elicit paresthesia or a motor response. It can be blocked as part of the midhumeral approach (see Ch. 20). The lateral cutaneous nerve of the arm can be blocked at the elbow by an injection just lateral to the tendon of the biceps at the elbow crease. A 23-G needle is inserted to a depth of 2–3 cm and injection of 4 mL of local anesthetic is made.

Ultrasound-guided approach

Intravenous access, ECG, pulse oximetry and blood pressure monitoring are established. For the ultrasound-guided axillary block, the patient is placed in the supine position with the upper limb to be blocked abducted to 90° and flexed at the elbow, with the hand resting adjacent to the head. The operator stands or sits adjacent to the side to be blocked. For the axillary block, the ultrasound screen is placed below the shoulder on the side to be blocked (Fig. 19.11).

The ultrasound transducer is placed on the skin perpendicular to the long axis of the axillary artery, vein, and the elements of the brachial plexus (transverse plane) (Fig. 19.12). The round, pulsatile axillary artery is identified, and then minor adjustments are made to obtain a view of accompanying neuronal structures. The axillary vein will be more compressible than the axillary artery and generally possesses a thinner vessel wall. Minimal pressure should be exerted on the ultrasound tranducer to identify veins.

Figure 19.12 Orientation of the ultrasound transducer when performing the ultrasound-guided axillary block.

Long axis approach

A 21-GA × 50-mm insulated needle or 2-inch Tuohy needle (18-G) is inserted parallel to the axis of the beam of the ultrasound transducer (Fig. 19.13). The needle is introduced vertically down, either through the lateral part of the pectoralis major, or biceps brachii, or coracobrachialis muscles. The operator can slide and tilt the transducer to maintain the needle tip within the plane of imaging as much as possible. The needle tip is slowly advanced under ‘real-time’ imaging to bring the needle tip to rest just deep to the axillary artery and adjacent to the radial nerve. A dual injection technique in which local anesthetic solution is injected both deep (radial nerve) and superficial (median and ulnar nerves) to the axillary artery should be employed.

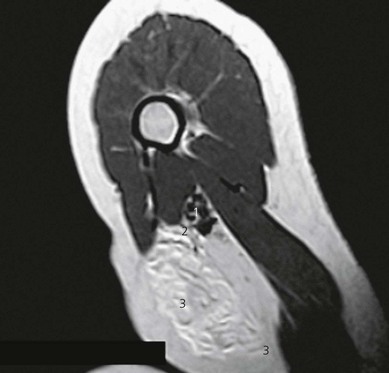

Once the needle tip has been confirmed by ultrasonography to lie in close proximity to the median, ulnar or radial nerves, this can be confirmed by using a nerve stimulator (Fig 19.14). Characteristic motor activity in the hand is seen. Test injections for assessment of local anesthetic spread should be small (0.5 to 2 mL). If the local anesthetic spread is not seen on the ultrasound screen, the injection should be stopped. The needle is readjusted to allow complete encirclement of the nerves with local anesthetic. Local anesthetic appears as a hypoechoic image (Fig 19.15). Typically, a decreased volume of local anesthetic is required compared to non-ultrasound-guided axillary blocks. Lidocaine, 2%, with epinephrine 1 : 200 000 and sodium bicarbonate 8.5% solution (1/10 mL of solution) 5–10 mL per nerve to a maximum of 40 mL may be used. Other longer acting local anesthetic agents may be substituted for longer lasting blocks if a catheter technique is not used.

The needle is withdrawn and the musculocutaneous nerve is identified in the corocobrachialis muscle or between the biceps and brachoradialis. Once the needle tip has been confirmed by ultrasonography to lie in close proximity to the musculocutaneous nerve, this can be confirmed by using a nerve stimulator. Characteristic motor activity is seen. A deposit of local anesthetic is made around the musculocutaneous nerve (Fig. 19.16). If the musculocutaneous nerve is not seen clearly, 10 mL of local anesthetic may be injected into the belly of the coracobrachialis muscle. A subcutaneous wheal is raised on the medial side of the arm to block the intercostobrachial nerve.

Short axis approach

A transverse image of axillary brachial plexus is obtained and then the needle is introduced in short axis of beam to reach the nerves individually (Figs 19.17 and 19.18). The disadvantage is that the needle is not clearly seen at all times and the needle tip position is indirectly ascertained by tissue motion and spread of local anesthetic. Between 4 and 10 mL of 2% lidocaine is deposited around each of the identified nerves.

Adverse effects

Bouaziz H, Narchi P, Mercier FJ, et al. The use of a selective axillary nerve block for outpatient hand surgery. Anesth Analg. 1998;86:746-748.

Chan VW, Perlas A, McCartney CJ, et al. Ultrasound guidance improves success rate of axillary brachial plexus block. Can J Anesth. 2007;54:176-182.

Finucane BT, Yilling F. Safety of supplementing axillary brachial plexus blocks. Anesthesiology. 1989;70:401-403.

Klaastad O, Smedby O, Thompson GE, et al. Distribution of local anesthetic in axillary brachial plexus block: a clinical and magnetic resonance imaging study. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1315-1324.

Lavoie J, Martin R, Tetrault JP, et al. Axillary plexus block using a peripheral nerve stimulator: single or multiple injections. Can J Anaesth. 1992;39:583-586.

Patridge BL, Katz J, Benirshoke K. Functional anatomy of the brachial plexus sheath: implications for anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1987;66:743-747.

Retzl G, Kapral S, Greher M, et al. Ultrasonographic findings of the axillary part of the brachial plexus. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2001;92:1271-1275.

Sites BS, Beach ML, Spence BC, et al. Ultrasound guidance improves the success rate of a perivascular axillary brachial plexus block. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50:678-684.

Vester-Andersen T, Christiansen C, Sorensen M, et al. Perivascular axillary block II: influence of volume of local anesthetic on neural blockade. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1983;27:95-98.