Axillary and Inguinal Lymphadenectomy

Introduction

British surgeon Sir Berkeley Moynihan stated, “Surgery of cancer is not the surgery of the organs; it is the surgery of the lymphatic system.” This statement is especially true of breast cancer and melanoma, in which specific operations are carried out to remove regional lymph node metastases. Lymph node dissection (LND) was the standard of care for staging as well as treating these patients. However, sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) changed the way surgeons stage and treat both breast cancer and melanoma (see Chapter 48).

Axillary Lymph Node Dissection

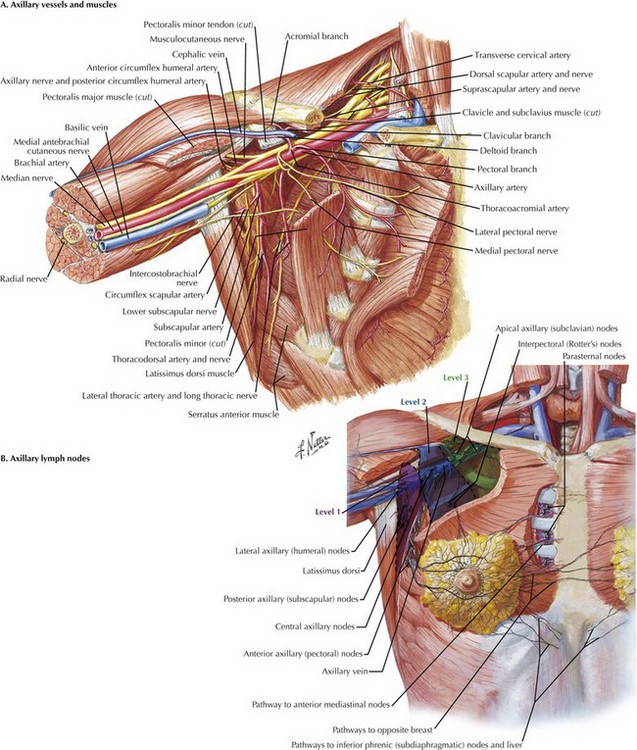

The boundaries of the axilla are the axillary vein superiorly, serratus anterior muscle and chest wall medially, subscapularis and teres minor posteriorly, latissimus dorsi laterally, and pectoralis minor and major muscles anteriorly (Fig. 49-1, A). These structures create a pyramid, with the apex positioned superiorly.

The lymph nodes of the axilla are divided into levels I, II, and III, on the basis of their anatomic location in relation to the pectoralis minor (Fig. 49-1, B). Level I nodes are lateral to the lateral edge of the pectoralis minor muscle, level II nodes are posterior to the pectoralis minor, and level III nodes are medial to the medial edge. Lymph nodes are also located between the pectoralis minor and major muscles (Rotter’s interpectoral nodes).

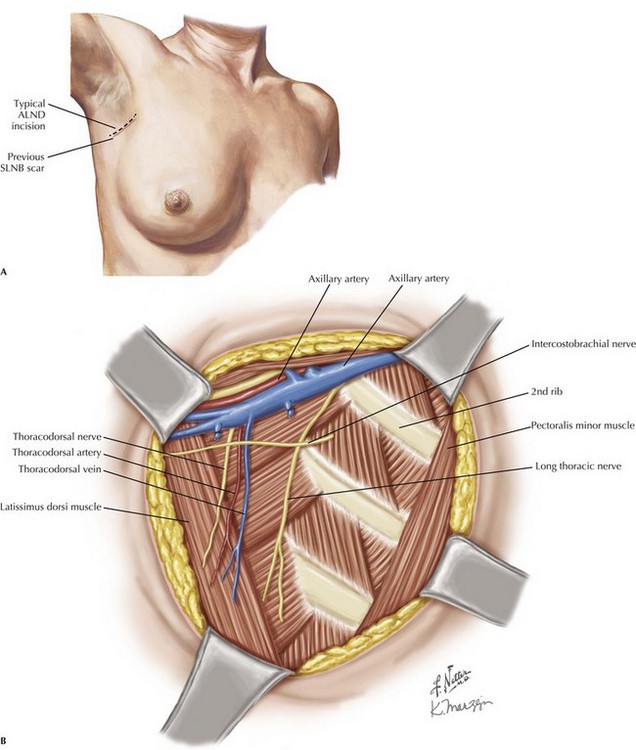

The patient should be positioned with the arm abducted 90 degrees. If the patient is undergoing a modified radical mastectomy, access to the axilla is gained through the mastectomy incision (see Chapter 46). Otherwise, a curvilinear incision at the inferior margin of the axillary hairline is typically used (Fig. 49-2, A). If present, a scar from previous SLNB should be used for the incision instead.

FIGURE 49–2 Axillary lymph node dissection.

ALND, Axillary lymph node dissection; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy.

After raising the skin flaps, the surgeon should identify the axillary vein (Fig. 49-2, B). This is typically performed by following the latissimus dorsi muscle to its insertion. Its tendon will course posterior to the lateral aspect of the axillary vein. Once identified, the axillary vein should be skeletonized inferiorly, with its inferior branches ligated. It is important to recognize the thoracodorsal vessels and nerve; these course inferiorly, but will actually enter the axillary vein posteriorly, and should not be ligated.

The thoracodorsal nerve is also important to identify, coursing laterally along the medial surface of the latissimus dorsi muscle (Fig. 49-2, B).

Inguinal Lymph Node Dissection

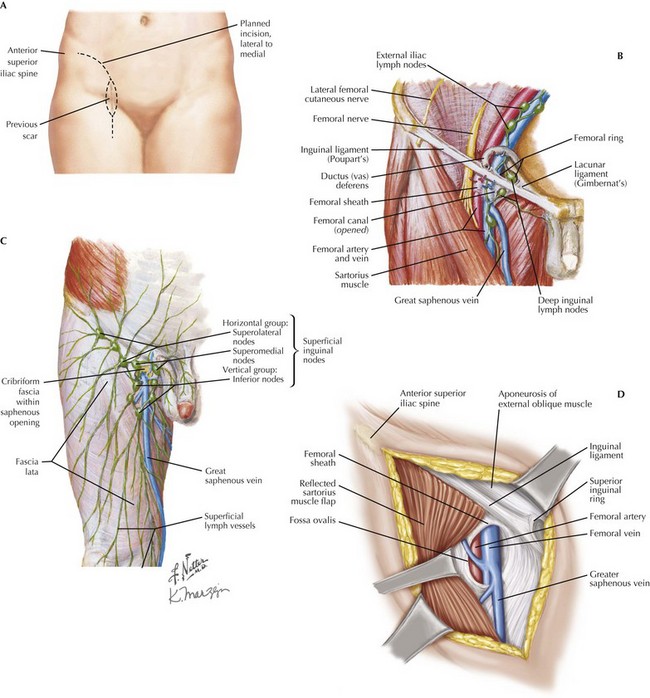

The lymphatic tissue of the inguinal region is divided into superficial and deep (Fig. 49-3). The superficial lymph nodes are those in the previously mentioned triangle, superficial to the fascia lata. The lymph tissue surrounds the greater saphenous vein medially and extends laterally and superiorly toward the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). These are the primary nodes removed during an ILND.

Access to this region is obtained through an elongated curvilinear incision (Fig. 49-3, A). Skin flaps are then raised laterally to the sartorius muscle and medially to the adductor longus muscle.

Typically, the surgeon starts the dissection by clearing the lymphatic tissue superior to the inguinal ligament and just medial to the ASIS. The dissection can then be carried inferiorly and laterally along the sartorius muscle (Fig. 49-3, B).

Once the lateral border of the specimen has been dissected, attention is turned to the medial border. While the medial border of the specimen is cleared, the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle will be identified with the superficial inguinal ring. Also identified is the femoral sheath, containing the femoral artery, vein, and nerve. Care is taken to identify the great saphenous vein, which will uniformly be superficial to the fascia of the medial thigh (Fig. 49-3, C). The great saphenous vein will then drain into the femoral vein through the saphenous opening or fossa ovalis.

If exposed femoral vessels are a concern after the specimen has been removed, a sartorius muscle flap may be used for coverage (Fig. 49-3, D). This maneuver involves dissecting the sartorius from its insertion on the ASIS and rotating it medially over the femoral vessels. This flap is then sutured into place along the inguinal ligament. Care should be taken to ensure that its medial blood supply remains intact.

Dzwierzynski, WW. Complete lymph node dissection for regional nodal metastasis. Clin Plast Surg. 2010;37(1):113–125.

Faries, MB, Thompson, JF, Cochran, A, et al. The impact on morbidity and length of stay of early versus delayed complete lymphadenectomy in melanoma: results of the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (I). Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(12):3324–3329.

Giuliano, AE, Hunt, KK, Ballman, KV, et al. Axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection in women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2011;305(6):569–575.

Schmidt, C. How to handle positive sentinel nodes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(24):1820–1823.