15 Avoiding Complications

Basic Principles

Useful Strategies

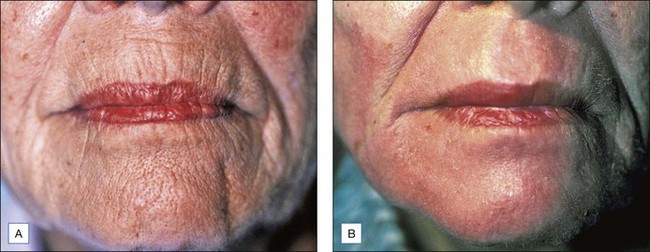

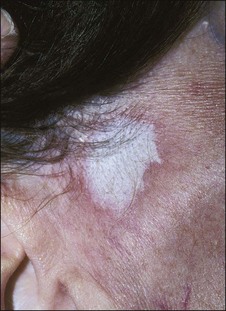

Figure 15.5 This patient has had an excellent result following a Baker’s peel without hyperpigmentation

See Boxes 15.1 and 15.2.

Educating Patients

• Discussing options

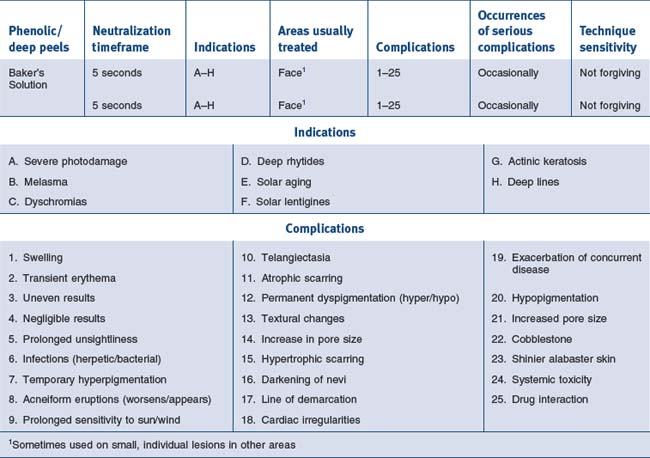

When discussing chemical peels with patients I arbitrarily divide them into three classes. Light peels, which are good for certain types of pigmentary disorder, textural abnormalities, and acne are described as ‘maintenance peels’ and do not require much downtime or carry much risk, but their results occur slowly (Fig. 15.7). Long term improvement is highly dependent on careful home programs which include the daily use of sunscreens and in many cases bleaching agents. Medium peels are described as capable of imparting a noticeable improvement in the patient’s appearance with the caveats of downtime while the patient is unpresentable, transient hyperpigmentation, and remote possibilities of more serious problems such as scarring. Deeper phenolic peels are described as more risky but absolutely necessary for deep wrinkles or severe photoaging. The possibility of serious complications, including hypopigmentation, scarring, systemic toxicity, and interaction with preexisting disease states or intraoperative medications, is carefully spelled out. I also discuss the medications we will be using or may need to use to carry out the procedure. These include local anesthetic with adrenaline, antibiotics, antiviral agents, and pain medications. It is also important to discuss the ‘no free lunch’ concept; that is, repeated applications of light peels ‘won’t make a dent in deep wrinkles’, but will often improve skin texture and dyspigmentation. Patients need to know that changes in skin color of either a transient or permanent nature are a major concern. As peels become deeper, the potential for permanent changes in skin color and lines of demarcation is greater (Fig. 15.8). Fair-skinned patients are told that there is a very high possibility of the skin being permanently lighter when deeper peels must be employed to efface deep rhytides. Very dark-skinned individuals are poor candidates for deep peels. Patients who tan well are told they might expect transient hyperpigmentation from any type of peel. Experience with curling irons and other forms of cutaneous trauma have often educated patients as to how their skin may respond to a peel.

The Psychology of Peels

Evaluating the Patient

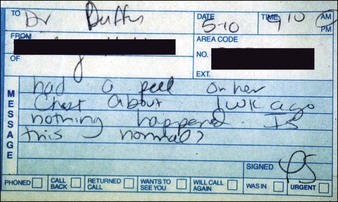

Patients exhibit their history on their skin (Fig. 15.9). Unlike other organs, this one is accessible. I ask them if they have been burned and look where they were burned. I ask them if they have had a brown spot after a burn or a light spot (Fig. 15.10). Look for surgical scars, ask about previous experience with burns (i.e., with curling irons) and whether the patient has had any procedures before. You frame your questions in the context of what effect something might have on the peel outcome. Do not forget to examine non-sun-exposed skin to see the patient’s true skin color.

• Personal habits/home regimens

Topical medications such as tretinoin (Retin-A), scrubs, cleansing granules, creams, and products bought at health food stores, as well as facial waxing, electrolysis, hair plucking, etc., can exert both preoperative and postoperative effects on peel outcomes (Fig. 15.11) Simple scrubbing to remove make-up immediately before a light peel can produce unexpectedly deep penetration of the agent. Sun exposure, certain types of medication, and certain skin types make a patient prone to specific types of complication.

• Sorting out patients

The most important evaluations have to do with patients who are going to need deep chemical peels. Patients with histories of hypertrophic scarring, dark-skinned patients, and patients with serious medical problems are not candidates for phenolic peels. Patients who do not use cosmetics (e.g., male patients) may be very poor candidates for deep chemical peels although they can certainly tolerate light and medium peels. I am particularly careful about employing periocular phenolic peels on patients who have had multiple blepharoplasties (Fig. 15.12) or who have undergone recent (less than 6 months) undermining plastic surgery or other types of resurfacing procedure. Heavy smokers are notoriously poor healers and are often poor candidates for deeper peels (Table 15.1).

Table 15.1 Factors in patient evaluation for phenol-based chemexfoliation

| General | General state of physical and mental health |

| Medications | |

| Pregnancy history | |

| History of herpes simplex | |

| Skin pigmentation classification evaluation | |

| History of hypertrophic scarring | |

| History of facial radiation or use of isotretinoin (Accutane) | |

| Realistic expectations | |

| Relative contraindications | Cardiac disease |

| Renal disease | |

| Hepatic disease | |

| Hormone replacement therapy | |

| Continued exposure to ultraviolet light | |

| History of radiation exposure or use of isotretinoin | |

| Contraindications | History of hypertrophic scarring or keloid formation |

| Fitzpatrick skin classification of IV–VI | |

| Recent facelift (deep chemical peeling in areas of recently undermined skin may result in vascular compromise and resultant scar formation) |

• Consultative ploys

Peel types/Patterns of complication

• Medium peels

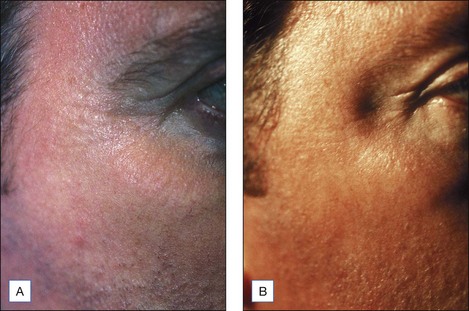

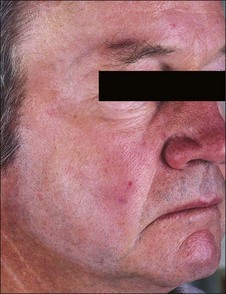

Most of the complications following medium peels consist of temporary dyschromias (usually hyperpigmentation) in darker skinned individuals and unpresentability for at least a week (Figs 15.14 and 15.15). Scarring is rare, but herpetic activation in susceptible individuals is common; accordingly, everyone who undergoes a medium peel receives at least 10 days of valacyclovir (Valtrex) 500 mg twice a day. Although downtime and the persistence of deep wrinkles are potential drawbacks, for many patients the texture, color, and vitality of the fresh skin is an enormous morale builder.

Light/Medium/Deep Peels: Complications and Observations

• Erythema

It takes experience to accurately judge the importance of the intensity and persistence of erythema as a marker of possible complications. The occurrence of erythema is directly related to peel depth as well as to hereditary and individual factors. In general, erythema fades following superficial peels in 3 to 5 days, medium peels in 15 to 30 days, and deep peels in 60 to 90 days. When intense erythema extends beyond these periods, it may be due to contact sensitization, the exacerbation of prior skin disease, or genetic susceptibility to erythema. Intense erythema may also be associated with scarring and delayed healing (Figs 15.16 and 15.17) One of the advantages in having tested patients for deeper peels is your ability to anticipate the duration of erythema. See Box 15.3.

• Scarring

Scarring is very rare following superficial and medium peels and uncommon following properly performed deep peels (Fig. 15.18). It can occur months after an uneventful deep peel, but quite often there will be signs or symptoms, most commonly in specific areas, which allow the practitioner to detect and treat these potential scars before they become hypertrophic.

Textural Changes

I have had one patient who developed ‘peau d’orange’ cobblestone textural changes following a periocular peel using straight phenol. He preferred his posttreatment appearance to his pretreatment rhytides (Fig. 15.19).

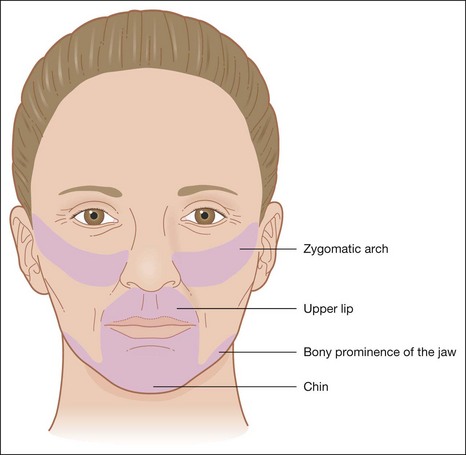

Areas of Predilection

Certain areas have a greater tendency for scarring. These include the zygomatic arch, the bony prominence of the jawline, the upper lips, and the chin (Fig. 15.20).

Scarring: The Red Flags

If I detect induration during the postoperative exam, I immediately institute treatment with class I topical steroids. I will often provide samples of these agents to patients to limit their use and ensure the patient will return. When hypertrophic scarring does occur, intralesional corticosteroids (triamcinolone acetonide 2.5–10 mg per mL) and Cordran tape used nightly are employed. It is interesting to note that dermabrasions and lasers produce scars in the same anatomical areas as deeper chemical peels (Figs 15.21 and 15.22).

Herpetic Scarring

In the era before antiviral medication, I observed four cases which developed mild atrophic scarring after herpes simplex complications. Two herpetic infections followed medium peels and two occurred following phenolic peels with atrophic scarring which was barely noticeable (Fig. 15.23).

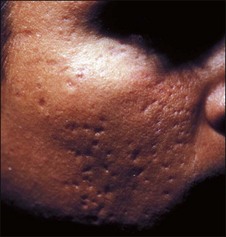

• Acne

Acneiform eruptions can occur following any type of peel and are most common following glycolic peels (Fig. 15.24). I have never personally observed cystic acne following any type of peeling. Acne following all types of peels may be initiated by occlusive ointments. Since such ointments can promote acne, patients are urged to use a very thin coat of antibiotic ointments, which should be removed before using the medications that I generally employ to minimize infections following medium and deep peels. Certain patients are more prone to acneiform eruptions; that is, those who have histories of acne or folliculitis. One of the major contributing factors to acne has to do with the use of soapless cleansers. The reinstitution of mild soap and water 3 or 4 days after deep peels and immediately after lighter peels is discussed.

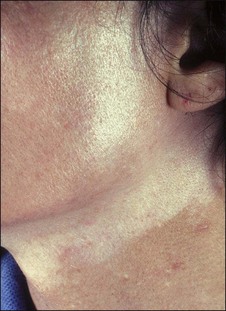

• Lines of demarcation

Deep peels routinely produce pigmentary changes (Fig. 15.25). I routinely feather the edge of deep peels with 25% to 30% TCA, particularly at the angle of the jaw and on the neck (Fig. 15.26) It is also worthwhile to peel earlobes when carrying out deep peels. Sun avoidance is the best treatment for patients who are prone to hyperpigmentation; it is also a good idea to carry out deeper peels during the winter months when there is simply less sun exposure. Lifestyle issues are a primary concern. Patients who cannot use or will not use sunscreens, or whose work or recreational habits keep them in the sun all the time, will be problematic. I do not routinely use any form of occlusion (tape, thymol iodide) except for deep rhytides involving the upper lip. Occlusion intensifies the wound, may increase the incidence of scarring and will definitely produce more hypopigmentation. When results are unsatisfactory I will repeat the peel again, sometimes using tape occlusion and salon-pas (oil of wintergreen) pads to promote a deeper peel. Patients are warned that the benefit–risk ratios change as the peel gets deeper.

Avoiding Complications Following all Types of Peel

• Pain

Glycolic acid and light TCA peels rarely require any kind of medication. Medium-depth TCA peels can be associated with brief but intense discomfort. For medium peels our usual method is to employ a combination of ice bags (Instant Cold Compresses, McKesson Medical-Surgical, Richmond, VA), a patient-held fan, and 2nd Skin. For medium peels the forehead seems to be the most uncomfortable area to peel and it is usually done first. A fan is provided as soon as the patient begins to report discomfort (Fig. 15.27) and then ice bags are applied long enough to chill the area (Fig. 15.28) The patient tells us when it is getting too cold. Immediately after blanching occurs, a hydrogel dressing is applied for several minutes (Fig. 15.29). This immediately stops the pain. Phenolic peels are not usually painful while they are being applied. Phenol itself is a topical anesthetic. However, the first night following a phenolic peel can be painful. Intraoperative pain is managed by nerve blocks and sublingual diazepam. Postoperatively following a deep peel the patient is sent home with an oral hydrocone/acetaminophen painkiller (Vicodin) for pain and zolpidem (Ambien) to aid sleep. Everything the patient is likely to need postoperatively should be prescribed well before the procedure is carried out and the use of these agents should be discussed. Having all the necessary medications at hand and discussing them before the peel, along with providing written instructions, is the best way to ensure compliance and proper post op care. Patients who are stoic and tolerate pain well are a particular risk for having complications associated with pain which they ignore.

• Preoperative preparation

Although many authorities advocate the use of extreme measures to degrease and defat the skin, including acetone and careful scrubbing, I have found this to be problematic. Vigorous rubbing to remove make-up is a common cause of irregular and sometimes deeper results following light chemical peels (Fig. 15.30). Patients should not wear any make-up on the day of the procedure at all. This includes particularly eye make-up, lipstick, etc. I also have patients wear a bandana to keep their hair off of the forehead and a shirt which is easy to remove over dressings. I discontinue scrubs and tretinoin, and substitute only mild soap and water, for several days before carrying out any type of peel on an individual basis. When you consider the fact that more than 20 variables and only 1.1 mm of skin separate peels that can scar from those that have almost no effect, it is easier to understand the continuing search for preparatory strategies to precisely control peel penetration. The rationale for vigorous degreasing of the face prior to peeling is that ‘a degreased face will lead to a more even peel’. However, vigorous degreasing with acetone, soap, alcohol or any combination of these also injures or destroys the epidermal barrier and allows more penetration of the peeling agent, resulting in deeper wounding and more complete and rapid absorption of the agent.

Observations/Procedural Ploys/Enhancing Results

• Alphahydroxy acid peels

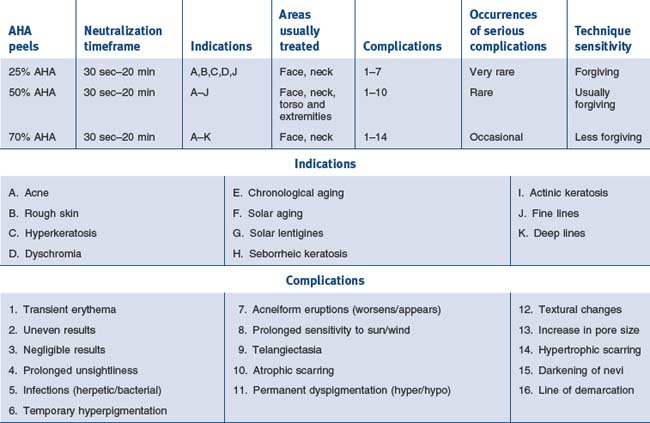

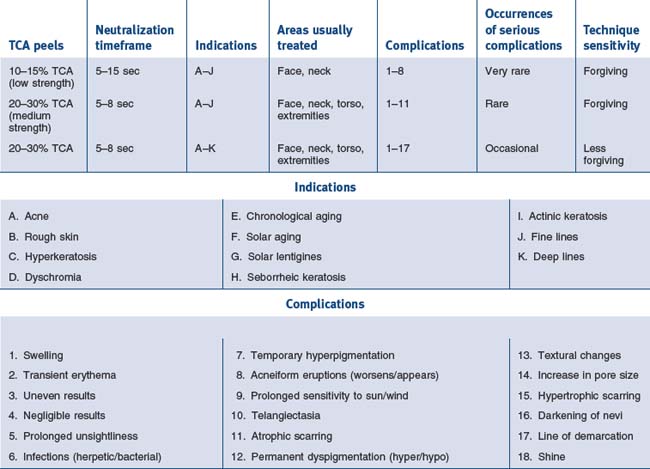

Younger patients often respond with vesiculation and unexpectedly deep peels to concentrations of alpha-hydroxy acids (AHAs) which are commonly used in older individuals (Fig. 15.31). We routinely use lower concentrations and shorter periods of contact in teenagers and young adults. Trivial changes in home treatment regimens (scrubs, tretinoin, exfoliants), as well as sun exposure, can produce unpredictably deep AHA peels. Some of our experiences with glycolic acid and light TCA peels are summarized in Tables 15.2 to 15.4. When carrying out AHA peels careful observation, looking for vesiculation, erythema or patient discomfort leads us to spot neutralize the area where this is occurring. We use soapless cleanser for this purpose. I have found the areas most susceptible to overly deep penetration to be the central and lateral cheek, the upper lip and the jawline. Patients with atopic dermatitis seem most susceptible to unexpectedly deep peels. Tolerance to AHA peels occurs over time and patients will often demand longer contact times. Exfoliation has been described as a felicitous event. Patients have associated desquamation with ‘getting their money’s worth’, particularly when undergoing a periocular peel. For patients with fine periocular wrinkling I sometimes combine full face AHA peels with 15% TCA periocularly, which will provide a little desquamation and satisfied patients.

• Baker’s solution

Baker’s solution is particularly effective when patients have palpable wrinkles and thick skin (Fig. 15.32).

Procedural Complications

Complications can occur at any point in the performance of chemical peels.

• Avoiding procedural complications/spillage/neutralization

Neutralizing Agents for Spillage

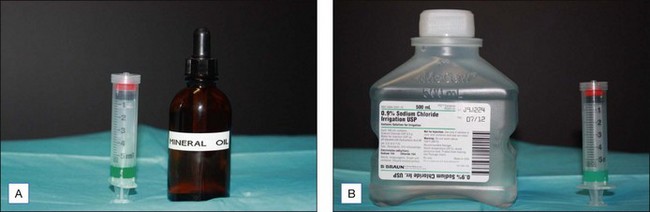

We use normal saline or bicarbonate of soda to neutralize TCA and AHA peels. The most important complication would be spillage into the eyes (an event which has fortunately never occurred in this office). In the case of TCA the eye is flooded with normal saline. If phenolic compounds are spilled into the eye, the eye should be flooded with mineral oil. The addition of water to phenolic agents increases their potency and absorption. We use a large syringe containing neutralizing agents as the easiest way to deliver them (Fig. 15.33).

• Setting up the table/avoiding procedural complications

General Rules

Q-Tip Practice

When using superficial and medium depth wounding agents I often use an OB/GYN swab which permits faster application of the escharotic (Fig. 15.34). More rapid application can also be effected using 3 small Q-tips. Be sure to roll them around as you press them to the side of the container individually because shared solution between the approximated swabs may drip. It is also worthwhile to practice using these swabs to determine the exact amount of solution you are applying. There is a certain level of light reflection that you will note. You must become accustomed to precision in this process. Wooden tipped applicators can also be tailored to size by peeling off varying amounts of the cotton and then recompressing it to make a smaller Q-tip. I have also practiced on my own forearm using a variety of peeling agents quickly applied and blotted off. This is a good way to determine the effect of volume on peeling depth. I used a surgical light to visualize the skin and determine the degree of wetness as I applied the solution.

Brody H. Complications of chemical resurfacing. Dermatologic Clinics. 2001;19:427-437.

Coleman WP, Lawrence N, editors. Skin resurfacing. Philadelphia: Williams and Wilkins, 1998.

Duffy DM. Informed consent for chemical peels and dermabrasion. Dermatologic Clinics. 1989;7:183-189.

Duffy DM. Cosmetic surgery and informed consent. Dermatologic Surgery. 1993;5:369-370.

Duffy DM. Alpha hydroxy acids/trichloroacetic acids risk/benefit strategies. Dermatologic Surgery. 1998;24(2):181-191.

Matarasso SL. Skin characteristics that affect peel penetration. Dermatologic Clinics. 1997;15(4):569-582.

Matarasso SL, Matarasso A. Analysis and treatment of the aging face. Dermatologic Clinics. 1997;15(4):549.

Menaker GM. Anesthesia for dermatologic surgery. Current Problems in Dermatology. 2001;13:80-85.

Monheit GD. Chemical peeling vs laser resurfacing. Dermatologic Surgery. 2001;27:213-214.

Monheit GD. Chemical peels. Current Problems in Dermatology. 2001;13:65-79.

Monheit GD. Fundamentals of cosmetic surgery. Dermatologic Clinics. 19(3), 2001.

Moy R, Lask G. Principles and techniques of cutaneous surgery. New York: McGraw Hill; 1996.

Rubin M. Manual of chemical peels. Philadelphia: JB Lippincot; 1995.

Zide BM, Swift R. How to block and tackle the face. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1998;101:840-851.

-hour procedure. Patients who undergo full face peeling should undergo cardiac monitoring to watch for phenol induced arrhythmias. I confine phenolic peels to one or two cosmetic areas at one sitting. Patients are hydrated by drinking several glasses of water prior to the procedure.

-hour procedure. Patients who undergo full face peeling should undergo cardiac monitoring to watch for phenol induced arrhythmias. I confine phenolic peels to one or two cosmetic areas at one sitting. Patients are hydrated by drinking several glasses of water prior to the procedure.