Chapter 26 Avoidance and Management of Complications of Otosclerosis Surgery

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

Medical Conditions

Fluctuating hearing loss, episodic vertigo, and low-frequency sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) may indicate endolymphatic hydrops. Care must be taken to avoid confusing the early conductive hearing loss of prior audiograms (which may falsely appear as SNHL) with endolymphatic hydrops. Patients with endolymphatic hydrops who undergo stapes surgery have a higher rate of SNHL (presumably from dilation of the saccule that contacts the stapes footplate where it is at risk during stapedectomy or stapedotomy) and chronic dizziness. This condition may be a contraindication to surgery.1

A history of multiple fractures or blue sclera may allow the diagnosis of osteogenesis imperfecta to be made preoperatively.2

Lifelong hearing loss in one ear should alert the surgeon to the possibility of congenital footplate fixation. Congenital footplate fixation carries a higher than usual risk of gusher and SNHL.3 A CT scan should be performed preoperatively in patients with suspected congenital footplate fixation to look for abnormal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)–perilymph connections that predispose to gusher. If a high risk of a gusher is found, amplification is recommended. A genetic pedigree focused on hearing loss is helpful in identifying patients with X-linked progressive mixed deafness. Patients with this disorder are rare and unique in that a conductive hearing loss is seen on the audiogram with intact stapedial reflexes.4,5 During surgery, a stapes gusher is encountered with the attendant risk of SNHL. Although males are typically affected, heterozygous females may exhibit milder audiologic abnormalities.6

Physical Examination

Various findings have an impact on upcoming surgery, including the following:

OPERATING ROOM

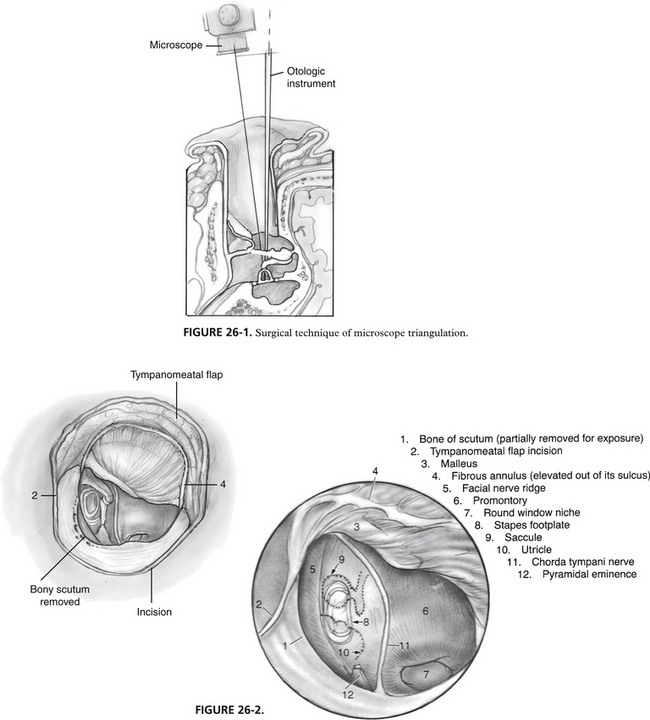

Surgical Technique Prerequisites for Residents

When surgeons are in training, much effort is put toward using proper methodology in the operating room. The technical difficulty associated with stapes surgery requires the surgeon to be facile with several key techniques. Residents and fellows should enter the operating room with previously demonstrated abilities in several areas. Preparation becomes more of an issue as the number of cases of surgically correctable otosclerosis decreases in most training programs.11 Limitation of hospital privileges may become more of an issue in the future if case availability precludes ascent to an acceptable level on an individual’s own learning curve. The following list is put forth for surgeons in training to use as preparation for successful performance of stapes surgery, while minimizing the risk of complications for the patient.

Surgical Equipment, Decisions, and Techniques

Prosthesis Type, Size, and Availability

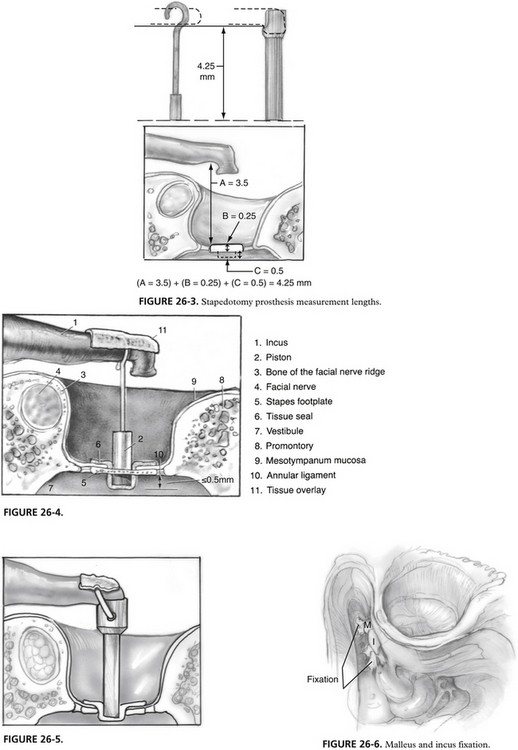

Three general prosthesis types exist: piston/wire, bucket handle, and polytef (Teflon) varieties. Few comparative data exist to compare the different types, but bucket handle prostheses may have a smaller incidence of incus necrosis in long-term follow-up. Piston/wire and Teflon varieties are probably easier to place. Self-crimping prostheses offer a new option in design, which may reduce the need for manual crimping.13 Long-term results with attention to incus necrosis would be of interest because the metal nitinol used in these prostheses contains a small percentage of nickel—a known cause of hypersensitivity reactions in other uses in humans such as jewelry.

Prostheses come in several different diameters, ranging from 0.3 to 0.8 mm most commonly. Experienced surgeons have indicated that 0.6 mm gives optimal results.14 Several studies have looked at alternative sizes, and there seems to be no degradation of results in the speech range down to 0.4 mm piston diameter.15 Prostheses measuring 0.3 mm show worse hearing results compared with prostheses measuring 0.4 mm.16 Lighter prostheses perform better in higher frequencies in situ in temporal bone studies.

Prosthesis length varies from patient to patient. Availability of the correct prosthesis is crucial to successful outcome. We prefer to use nonferromagnetic materials, in particular titanium bucket handle prostheses. Table 26-1 outlines the prostheses stocked in our operating suite. Note the inclusion of the incus replacement prosthesis (see the later discussion on incus necrosis).

Laser Stapedotomy versus Drill Stapedotomy

It is generally agreed among most surgeons that use of the laser reduces the risk of mechanical transmission of vibratory energy to the inner ear, making it a safer technique. Comparative data from primary stapedotomy question this tenet, viewing both techniques as effective and safe.17 Use of a laser does improve results in revision cases.18 In all cases, proper use of the laser reduces bleeding associated with tissue ablation, which is an advantage. Both techniques are accepted within the standard of care.

Stapedectomy versus Stapedotomy

For most otologists, the procedure of choice for otosclerosis has become stapedotomy. Compared with stapedectomy, the limited fenestra improves results in the high frequencies, and most authors report a reduction in SNHL as a result of the procedure.19–21 Stapedotomy carries a smaller rate of postoperative vestibular complaints. Stapedectomy remains a valuable alternative in the experience of some surgeons. Occasionally, a stapedotomy needs to be converted to a complete stapedectomy.

Stapedotomy Site

The stapedotomy should be placed posteroinferiorly in the central footplate region (see Fig. 26-2). This area does not overlay the saccule or utricle and gives the most margin for overpenetration on the medial side of the footplate. It is possible, and frequently necessary, to move the stapedotomy to other areas of the footplate because of anatomic concerns of the incus or structures surrounding the oval window niche.

Footplate/Vestibular Relationships

Almost all patients have a minimum safe distance of 1 mm between the medial surface of the footplate and the utricle or saccule. Penetration of the vestibule by more than 1 mm with instruments or the prosthesis may impinge the structures of the membranous labyrinth, producing vertigo with prosthesis movement. Perforation of the saccule or utricle may induce SNHL, vertigo, or both.22,23

Laser Type

Controversy regarding laser type, efficacy, and safety has arisen since the first laser stapedotomy performed by Perkins.24 Visible wavelength lasers have the added advantage of absorption by blood, providing hemostasis. Appropriate adjustment of the CO2 laser also can provide hemostasis. Visible wavelength lasers have the technologic advantage of being able to use the laser light as the aiming beam; this avoids needing to produce a visible wavelength light that also serves as the aiming beam, which may not accurately reflect where the therapeutic beam is aimed (as can occur with the helium-neon aiming beam with CO2 lasers). Theoretical concerns regarding absorption of energy from the KTP or argon laser by the inner ear have been voiced by several authors (visible wavelength lasers are transmitted through clear fluid). Several studies have proven equal safety of visible wavelength and CO2 lasers for laser stapedotomy.25,26

Stapedotomy in Children

Stapedotomy can be performed safely in children with surgical results as least as good as the results expected in adults.27 Children should be beyond the age of otitis media, and surgery should be attempted only under general anesthesia. Congenital footplate fixation requires special considerations, as discussed later.

MANAGEMENT OF COMPLICATIONS ENCOUNTERED AT PRIMARY SURGERY

Malleus and Incus Fixation

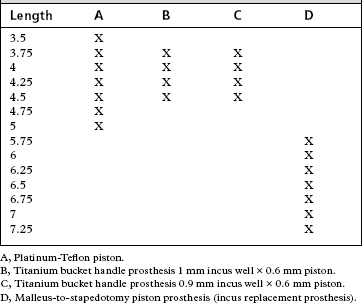

Routinely, every case should include a check of the mobility of the malleus and incus. Patients with otosclerosis have a higher incidence of hyalinization of the anterior malleal ligament, which may be the sole cause or a contributing factor in the conductive hearing impairment.29 This is best performed after division of the incudostapedial joint with gentle upward pressure on the undersurface of the handle of the malleus, while watching for movement at the lenticular process of the incus. Documentation of the state of function of the first two ossicles is crucial when evaluating and planning revision for patients who do not experience adequate improvement of hearing with the primary procedure. In addition, in approximately 1% of cases, fixation of the malleus and incus is discovered, allowing rectification during the primary procedure. A small or moderate amount of limitation of motion of the malleus and incus usually produces little in terms of conductive hearing loss, which is usually low frequency in nature. In cases where doubt exists about the severity of malleus and incus fixation with clearly appreciated footplate fixation, performance of the stapedotomy with postoperative testing before work on the malleus or incus or both shows good judgment.

Operative repair of the situation is best addressed with a mastoidotomy with extension into the root of the zygoma to allow exposure of the body of the incus and head of the malleus in the epitympanum (Fig. 26-6). Usually, fixation occurs at the superior malleolar ligament from the tegmen. The posterior process of the incus may also be involved, as can any suspensory ligament of the ossicular chain. Removal of offending bone and restoration of ossicular mobility can be performed with a laser.30 Larger wattages are necessary than those used on the stapes superstructure or footplate (we use the KTP laser with 5 to 8 W on continuous mode). A blood-soaked Gelfoam is placed as a “backstop” to protect the facial nerve with higher laser settings. Although a drill can remove bone as well, laser use minimizes the risk of transmission of damaging vibratory energy to the vestibule. If the stapes is also fixed, it is prudent to remove the stapes superstructure before mobilization of the malleus and incus. If the conductive hearing loss resides solely in the fixation of the malleus and incus, disarticulation of the incudostapedial joint to produce discontinuity is mandatory in cases where the laser is not used to remove the fixation (sometimes interposition of Gelfoam is necessary to keep the lenticular process of the incus from touching the capitulum of the stapes). Removal of bone in the mastoid can be performed comfortably in most patients under sedation if necessary.

Persistent Stapedial Artery and Vascular Anomalies

Rarely, a persistent stapedial artery is encountered running from the facial nerve through the arch of the stapes to the carotid artery. Even less commonly, an aberrant carotid is seen. Although the persistent stapedial artery is not seen with otoscopy, an aberrant carotid is visible, and can be mistaken for a glomus tumor. Most vascular anomalies occur in women.31 If a persistent stapedial artery is small, fine bipolar cautery or laser coagulation may be used to remove the vessel from the field, allowing completion of the procedure. With larger arteries, it may be prudent to stop the procedure and prescribe amplification.

Tympanosclerosis

One may discover ossicular fixation secondary to tympanosclerosis of the stapes footplate. Fixation of this type is not as vascular as otosclerosis and has a softer texture. Stapedotomy may be performed safely. Excellent early results may be achieved with some attrition over time.32–34

Osteogenesis Imperfecta

Osteogenesis imperfecta is a congenital disorder of bone inherited via autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive patterns. The triad of blue sclera, multiple fractures, and conductive hearing loss is known as Van der Hoeve’s syndrome. The mean age of hearing impairment is in the early 20s.35 Footplate fixation accounts for the conductive hearing loss. Footplates are typically thick and frequently very soft with increased vascularity, whereas crura may be atrophic.36 Progressive SNHL can be seen in a few patients.37 Despite a small increase in risk of SNHL in some series, stapedotomy remains a viable treatment for conductive hearing loss associated with this disorder.38

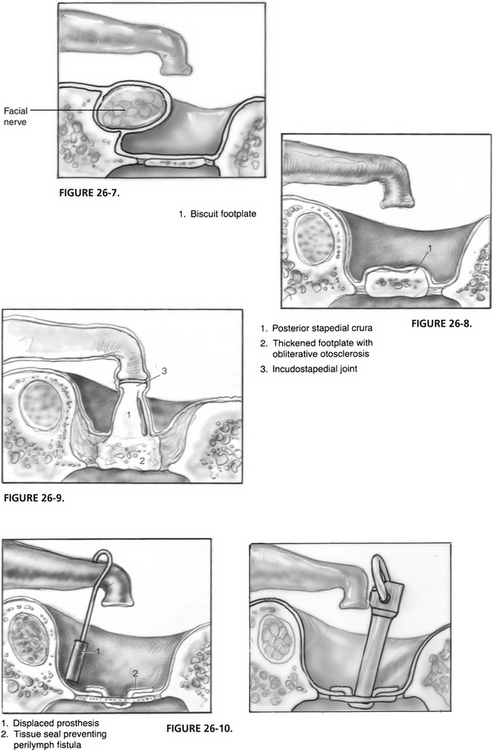

Overhanging Facial Nerve

The facial nerve can provide obstruction to completing successful stapes surgery and is encountered regularly (Fig. 26-7). Recognition of an aberrant or dehiscent facial nerve prevents injury. Twenty-five percent to 40% of temporal bone specimens include dehiscence of the bony fallopian canal. Inconveniently located dehiscence may be sites of trauma secondary to surgical instrumentation. Local anesthetic agents may also penetrate these areas more readily, causing postoperative facial paralysis. The reader is referred to Chapter 29 for management options. In some situations, coupling the technique used for narrow oval window enlargement becomes necessary for prosthesis placement. A dehiscent facial nerve rarely prevents successful surgical repair.

Narrow Oval Window Niche

Anatomic abnormalities or impingement on the oval window area by the facial nerve can produce narrowing so that prosthesis placement is difficult or impossible. Enlargement of the inferior margin of the oval window niche at the midpoint of the footplate just anterior to the junction of the subiculum and promontory can facilitate surgical success.39 Intermittent laser pulses produce char that is then removed with a rasp. Significant extra space can be gained with this technique because the bone is quite thick in this area. Care must be taken to prevent caloric overstimulation of the vestibule. In addition, the stapedotomy can be shifted inferiorly to the margin of the oval window to facilitate prosthesis placement. Overlapping the margin of the oval window can be dangerous because Reissner’s membrane and the basilar membrane occupy this area in the cochlear hook region.40

Congenitally Ectopic Facial Nerve

The facial nerve may be congenitally malpositioned entirely on the promontory side of the footplate, split with a portion on either side of the footplate, or pass through the arch of the stapes.41,42 The stapes crura are not attached to the footplate a high percentage of the time with abnormalities in the course of the facial nerve. If prosthesis placement can proceed without iatrogenic injury to the nerve, the case can be completed with the prosthesis placed above, between, or around the aberrant nerve. (Alternatively, few hearing devices produce facial paralysis!)

Biscuit Footplate

Manipulation of a biscuit footplate puts the patient at increased risk for footplate mobilization and SNHL (Fig. 26-8). Use of the laser allows removal of bone and performance of a footplate fenestra without significant energy transfer to the tenuous footplate. Care should be used to prevent heat transfer to the vestibule, which may put the inner ear at risk. Cases performed under local sedation allow the surgeon to sense when caloric stimulation begins for the patient as vertigo frequently begins. Cessation of laser use for several minutes allows cooling of the footplate and vestibule, allowing resumption of the bone removal process. Patients operated on under general anesthesia should have no more than 8 to 10 laser pulses in a row without allowing time for cooling. Excellent results are obtainable for the patient and surgeon.

Obliterative Otosclerosis

Obliteration of the oval window niche occurs from otosclerotic bone growth in some cases (Fig. 26-9). The area should not be drilled out using a diamond burr because reactivation and reformation of the otosclerotic growth may be stimulated, and a higher rate of SNHL may be realized. Bleeding is also frequently produced with such a technique.43–45 Footplate fenestration may be accomplished as with a biscuit footplate outlined previously.

Perilymphatic Gusher

The normal anatomic arrangement of the human ear allows flow of CSF into the perilymphatic space. Normally, extremely small connections between these two spaces exist. With enlarged connections (usually through the fundus of the internal auditory canal, through the modiolus of the cochlea, and possibly through an enlarged cochlear aqueduct), a rapid outpouring of perilymph occurs when the stapes footplate is removed as a barrier in either a stapedectomy or a stapedotomy. Known as a “gusher,” such an event can be associated with SNHL.46 Conditions known to increase the chance of this condition include enlarged vestibular aqueduct syndrome, X-linked progressive mixed deafness, congenital footplate fixation, and Mondini’s dysplasia.

Several authors recommend creation of a small control hole in the footplate before removal of the footplate if the technique of stapedectomy is used. It is much easier to handle this complication through a small footplate hole than with the entire footplate out. In the event a gusher is encountered that cannot be controlled with a vein and prosthesis, more extensive management becomes necessary. In this situation, management is similar to that of a CSF leak. Tissue is used to provide a seal for the oval window fenestra, preferably with a prosthesis providing tamponade (which is not always possible). A lumbar drain is placed to decrease the cerebrospinal and perilymph pressure. Postoperatively, the head of the bed is elevated at least 30 degrees, and bed rest is employed. Fluids are restricted, and oral acetazolamide may be prescribed. Prophylactic antibiotics are given.47 The patient is discharged 24 hours after the lumbar drain is clamped with no further fluid leak as judged by CSF rhinorrhea. Bed rest at home is recommended for another week.

Blood within the Vestibule

A bloodless field increases safety by allowing the surgeon to see all structures clearly. In addition, blood in the vestibule is associated with an increase in risk for sensorineural hearing impairment in animal studies and human experience.48 The ultimate surgical technique employs a completely bloodless oval window before entrance into the vestibule through the stapes footplate.

Sensorineural Hearing Loss

SNHL is perhaps the most disappointing and devastating complication for the patient and the surgeon. Complete or partial hearing loss can result from the most meticulously and appropriately performed stapes procedure. Most cases probably are due to surgical trauma, however. Intraoperative electronystagmographic studies performed during stapedectomy in the prelaser era implicate suctioning over the vestibule, drilling near the footplate or oval window niche, and manipulation of the footplate as the great offenders for vestibular and presumably for cochlear damage.49

COMPLICATIONS AFTER PRIMARY SURGERY

Medical Management

Acute Otitis Media

Acute otitis media occurs in the postoperative period in patients who have had stapes surgery. The infection is usually successfully treated without sequelae. Entrance of pathogenic organisms into the perilymph can produce SNHL and vestibular damage. Progression into the CSF has been reported with meningitis.8,50–52 Prophylactic antibiotics have not been shown to reduce the incidence of this complication and carry some risk, and are not recommended.

Barotrauma

Iatrogenic rearrangement of the normal anatomy may increase a patient’s chance of experiencing barotrauma of the inner ear after stapes surgery. We allow patients to fly in pressurized aircraft 2 days after surgery when a vein graft has been placed. No restrictions are placed for snorkeling or scuba diving after healing has occurred, provided that patients are able to self-insufflate through an open eustachian tube (as all patients should have for these activities even without previous ear surgery). A wide range of practices regarding postoperative restrictions exists among otologists. No significant differences have been shown in the prevalence of barotrauma based on individual physicians’ recommendations for these activities.53

Delayed Facial Nerve Paralysis

A few cases of delayed facial nerve paralysis have occurred. Typically, the onset of paralysis occurs 7 to 10 days after surgery and is associated with pain. Treatment with a tapering dose of steroids (initial dosing of prednisone, 30 mg twice daily tapering over 2 weeks) has brought about resolution in all cases.54

Hyperacusis

Almost all patients have some degree of phonophobia postoperatively. Reassurance is adequate treatment, with only a few patients experiencing a persistent problem.55

Binaural Diplacusis

The same tone is perceived as different pitches in each ear in one third of patients after stapes surgery. By 6 weeks postoperatively, the condition fades without treatment.56

Otosclerotic Inner Ear Syndrome

Balance disturbance may result from ongoing growth of the otosclerotic focus postoperatively. Patients complain of brief episodes of motion not severe enough to be termed spinning or of diffuse, persistent unsteadiness. Such complaints are hard to distinguish from perilymphatic fistula and other causes of postoperative vestibular complaints. A high percentage of patients respond to the administration of fluoride when the complaint is due to ongoing otosclerosis.57 We currently use calcium fluoride (Monocal), 2 tablets twice daily. Sodium fluoride (Flurocal) has been associated with gastric intolerance in a higher percentage of patients.58

Sensorineural Hearing Loss Progression

Otosclerosis induces a progressive SNHL in many patients.59–65 Otosclerosis can be a cause of SNHL without a conductive component.66 It can be extremely disappointing to see an excellent surgical result deteriorate because of progressive SNHL, leaving the patient with functionally significant hearing impairment. Convincing data exist that establish the role of fluoride in stabilizing SNHL associated with otosclerosis.67–73 We place patients with SNHL present at the time of surgery on calcium fluoride (2 tablets orally twice daily with meals) for 1 to 2 years after surgery. If hearing remains stable at that time, the treatment is stopped. Any further progression prompts further treatment. Patients who exhibit new-onset SNHL in the postoperative period are treated similarly. Patients whose otosclerosis produces severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss can be expected to do well with cochlear implants, although there is a higher incidence of facial nerve stimulation in such applications.74

Surgical Management

Conductive Hearing Loss

Return of conductive hearing loss is the most commonly experienced postoperative complication of stapedotomy, accounting for 50% to 70% of revision surgical procedures.76–80 Although exact rates are difficult to determine, 10% to 20% of cases require revision sometime during the patient’s lifetime. With the decrease in primary surgery, many experienced stapes surgeons perform revision surgery a significant percentage of the time.

Prosthesis Displacement

Hearing deterioration may be acute, as the prosthesis becomes dislodged, or chronic, as it is gradually displaced out of position (Fig. 26-10). This complication may be encountered many years after stapes surgery. The diagnosis is definitively made at reoperation, but may be suspected based on history and tuning fork and audiometric testing.

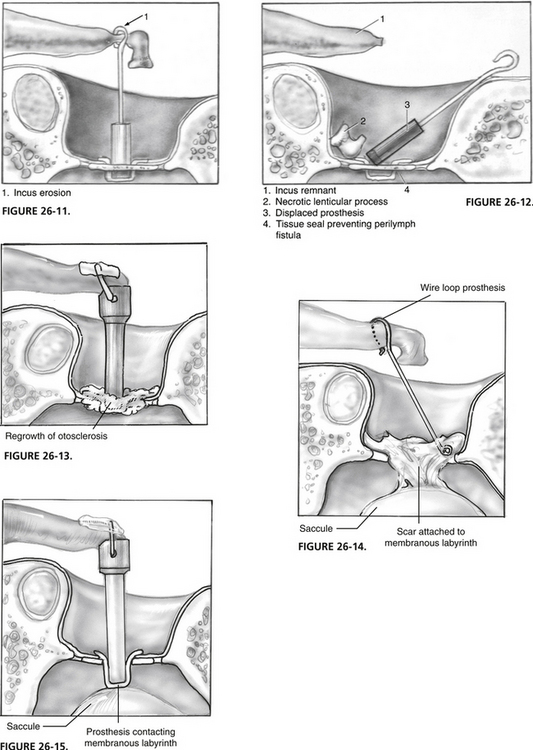

Incus Necrosis

Division of the incudostapedial joint reduces the blood supply to the distal incus. Vessels from the stapes superstructure provide a little perfusion, whereas vessels coursing from the stapedial tendon bring most of the blood to the distal incus. Channels for blood flow exist within the interior of the long process of the incus. Necrosis of this incus leads to prosthesis displacement (Figs. 26-11 and 26-12). Prostheses that crimp onto the incus may reduce further the only remaining blood supply coming from the direction of the body of the incus, increasing the chance of this complication. For this reason, some surgeons prefer a bucket handle prosthesis. Incus necrosis still occurs, no matter which prosthesis is used.

FIGURE 26-13 Otosclerosis regrowth.

FIGURE 26-14. Adhesions from oval window to membranous labyrinth.

FIGURE 26-15. Excess prosthesis length, which contacts the membranous labyrinth.

If an adequate amount of incus remains, a shepherd’s crook prosthesis can be used by crimping the prosthesis more proximally on the incus during revision surgery. Occasionally, it becomes necessary to bend the prosthesis around the facial nerve ridge to establish footplate contact. The amount of bend affects the length of prosthesis needed. In selected cases, application of an otologic cement may aid in prosthesis stabilization after repositioning or replacement.81 In the event the remnant incus cannot be used, the tympanic membrane is elevated from the lateral surface of the malleus, and a malleus-to-stapes footplate prosthesis is placed. Table 26-1 lists sizes of our preferred malleus-to-footplate prostheses.

Otosclerotic Regrowth

Otosclerosis continues to grow in some patients, producing prosthesis fixation or displacement (Fig. 26-13). At revision surgery, the cause of the conductive hearing impairment is best handled with prosthesis removal, laser enlargement of the stapedotomy, and placement of a fresh prosthesis.

Wire Loop Prosthesis

The dominant prosthesis used for many years for stapes surgery was the wire loop prosthesis. The wire loop prosthesis was used only in the technique of total stapedectomy. Return of conductive hearing impairment prompting revision frequently shows displacement of the oval window portion of the prosthesis. Because tissue was used to seal the stapedotomy in most instances, a large amount of scar usually exists in the oval window (Fig. 26-14). A properly adjusted laser allows removal of scar surrounding the oval window loop of the prosthesis. The wire loop prosthesis should not be grasped and removed because it frequently is attached to vital structures of the vestibule, producing a high chance of inner ear injury. It is necessary when revising these cases to leave a small membrane of tissue, if possible, over the vestibule, or to insert autologous tissue with the new prosthesis.

Long Prosthesis Overinsertion

Overinsertion of the long prosthesis into the vestibule may cause a sensation of vertigo with loud sounds (Fig. 26-15). If this occurs, prosthesis removal and replacement with a shorter version usually fixes the difficulty. Palpation of the freshly placed prosthesis by putting gentle pressure on the incus in patients under sedation identifies a too-long prosthesis while still in the operating room. With a too-long prosthesis, the patient experiences vertigo with this maneuver. Care should be taken to avoid overstimulation of the vestibule, which could produce SNHL.

Loose Prosthesis Syndrome

Loose coupling of the prosthesis to the incus produces characteristic sensations of sound distortion (see Fig. 26-11).77 A large conductive hearing loss may not exist on the audiogram; tuning forks may also be normal. Occasionally, severe symptoms of this type prompt revision surgery. Tightening the crimp or changing to a different prosthesis can completely alleviate the difficulty.

Perilymphatic Fistula

Perilymphatic fistula is a cause of postoperative dysequilibrium and SNHL. The signs and symptoms of perilymphatic fistula may be indistinguishable from normal postoperative findings.78,79 In addition, a perilymphatic fistula may be discovered at revision surgery with an asymptomatic patient. Fistulas seem to be much less common after stapedotomy compared with stapedectomy. Progressive SNHL or unremitting vestibular complaints or both may prompt re-exploration. Repair of a symptomatic perilymphatic fistula relieves vestibular complaints in approximately half of patients.

Reparative Granuloma

Reparative granuloma is defined as a histologically confirmed formation of granulation tissue involving the prosthesis and oval window in a symptomatic patient after stapes surgery. The lesion does not involve granulomatous inflammation.80 This unusual complication occurs in approximately 0.1% of all cases. Presenting symptoms usually surface 1 to 6 weeks after surgery, and most commonly involve vertigo, but may include SNHL, progressive mixed hearing loss, sudden hearing loss, and tinnitus.82 Management includes either immediate surgery with removal and replacement of prosthesis and grafting material or nonsurgical management comprising steroids and antibiotics. Surgical intervention seems to give a better outcome.

SURGICAL RISK REDUCTION IN REVISION SURGERY

Although variation occurs based on the adequacy and technique of primary surgery, revision stapes surgery is needed in a significant percentage of patients. Series from nations with centralized health care provide the best data because of controlled follow-up. A revision rate of 13% in one series of 4000 cases amassed by several surgeons has been reported.85 Revision may be necessary immediately after primary surgery or many years later, with an average time to revision of 8 to 12.5 years.86,87

Success rates for revision surgery have improved significantly over the past 20 years. Early reports found postoperative conductive hearing loss of 10 dB or less in less than half of patients.72,88 Modern results more closely approach those of primary surgery with closure to 10 dB or less in 90% of cases.

Use of a laser improves surgical outcome. Meta-analysis of revision stapes surgery comparing 11 studies without laser use (N = 1147 patients) with 4 studies that employed laser technique (N = 170 patients) showed a statistically significant (P = .0002) advantage in terms of safety and efficacy. Postoperative air-bone gaps of 10 dB or less were accomplished in 69% of cases in which a visible wavelength laser was used, whereas only 51% of patients on whom standard techniques were used had the same results.89

The risk of SNHL is greater with revision surgery. Rates seem to be higher when revision of stapedectomy is undertaken compared with cases with stapedotomy as the primary technique. Oval window drill-out is associated with an unacceptably high rate of inner ear injury and hearing loss and should be avoided.72 Reported rates of SNHL with revision surgery vary from 0 to 7.6%.44,72,86,90 We currently quote patients a rate of SNHL twice that of primary surgery.

1. Smith M.F.W., Hopp M.L. 1984 Santa Barbara State-of-the-Art Conference on Otosclerosis: Results, conclusions, consensus. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1986;95:1-4.

2. Garretsen T.J.T.M., Cremers W.R.J. Ear surgery in osteogenesis imperfecta. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;116:317-323.

3. Olson N.R., Lehman R.H. Cerebrospinal fluid otorrhea and the congenitally fixed stapes. Laryngoscope. 1968;78:352-360.

4. Snik A.F., Hombergen G.C., Mylanus E.A., et al. Air-bone gap in patients with X-linked stapes gusher syndrome. Am J Otol. 1995;16:241-246.

5. Cremers C.W. Audiologic features of X-linked progressive mixed deafness syndrome with perilymphatic gusher during stapes surgery. Am J Otol. 1985;6:243-246.

6. Cremers C.W., Huygen P.L. Clinical features of female heterozygotes in the X-linked mixed deafness syndrome (with perilymphatic gusher during stapes surgery). Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1983;6:179-185.

7. Brown J.S. Meningitis following stapes surgery: The pathway of spread to the intracranial cavity. Laryngoscope. 1967;77:1295-1303.

8. Clairmont A.A., Nicholson W.L., Turner J.S. Pseudomonas aeruginosa meningitis following stapedectomy. Laryngoscope. 1975;85:1076-1083.

9. Snyder B.D. Delayed meningitis following stapes surgery. Arch Neurol. 1979;36:174-175.

10. Gordon M.A., Silverstein H., Willcox T.O., et al. A re-evaluation of the 512-Hz Rinne tuning fork test as a patient selection criterion for laser stapedotomy. Am J Otol. 1998;6:712-717.

11. Harris J.P., Osborne E. A survey of otologic training in U.S. residency programs. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;116:342-345.

12. Majoras M. Electronystagmography during stapedectomy. Int Surg. 1967;47:323-327.

13. Rajan G.P., Atlas M.D., Subramaniam K., Eikelboom R.H. Eliminating the limitations of manual crimping in stapes surgery? A preliminary trial with the shape memory nitinol stapes piston. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:366-369.

14. Shea J.J. Thirty years of stapes surgery. J Laryngol Otol. 1988;102:14-19.

15. Fisch U. Stapedectomy versus stapedotomy. Am J Otol. 1982;4:112-117.

16. Grolman W., Tange R.A., de Bruijn A.J., et al. A retrospective study of the hearing results obtained after stapedotomy by the implantation of two Teflon pistons with a different diameter. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1997;254:422-424.

17. Sedwick J.D., Louden C.L., Shelton C. Stapedectomy versus stapedotomy: Do you really need a laser? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:177-180.

18. Wiet R.J., Kubek D.C., Lemberg P., et al. A meta-analysis review of revision stapes surgery with argon laser: Effectiveness and safety. Am J Otol. 1997;18:166-171.

19. Persson P., Harder H., Magnuson B. Hearing results in otosclerosis surgery after partial stapedectomy, total stapedectomy, and stapedotomy. Acta Otolaryngol. 1997;117:94-99.

20. Kursten R., Schneider B., Zrunek M. Long-term results after stapedectomy versus stapedotomy. Am J Otol. 1994;15:804-806.

21. Glasscock M.E.III, Storper I.S., Haynes D.S., et al. Twenty-five years of experience with stapedectomy. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:899-904.

22. Anson B.J., Bast T.H. Anatomical structure of the stapes and the relation of the stapedial footplate to vital parts of the labyrinth. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1958;67:389-399.

23. Pauw B.K.H., Pollack A.M., Fisch U. Utricle and saccule and cochlear duct in relation to stapedotomy: A histological human temporal bone study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991;100:966.

24. Perkins R.C. Laser stapedotomy for otosclerosis. Laryngoscope. 1980;91:228-241.

25. Vernick D.M. A comparison of the results of KTP and CO2 laser stapedotomy. Am J Otol. 1996;17:221-224.

26. Antonelli P.J., Gianoli G.J., Lundy L.B., et al. Early post-laser stapedotomy hearing thresholds. Am J Otol. 1998;19:443-446.

27. Robinson M. Juvenile otosclerosis: A 20-year study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1983;92:561-565.

28. Lippy W.H., Schuring A.G. Stapedectomy revision following sensorineural hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;92:580-582.

29. Nandapalan V., Pollak A., Langner A., Fisch U. The anterior and superior malleal ligaments in otosclerosis: A histopathologic observation. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23:854-861.

30. Seidman M.A. A new approach for malleus/incus fixation: No prosthesis necessary. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:669-673.

31. Pirodda A., Sorrenti G., Marliani A.F., et al. Arterial anomalies of the middle ear associated with stapes ankylosis. J Laryngol Otol. 1994;108:237-239.

32. Tos M., Lau T. Tympanosclerosis of the middle ear: Late results of surgical treatment. J Laryngol Otol. 1990;104:685-689.

33. Gormley P.K. Stapedectomy in tympanosclerosis. Am J Otol. 1987;8:123-130.

34. Giddings N.A., House J.W. Tympanosclerosis of the stapes—hearing results for various surgical treatments. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;107:644-650.

35. Pedersen U., Elbrond O. Stapedectomy in osteogenesis imperfecta. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1983;45:330-337.

36. Garretsen T.J.T.M., Cremers C.W.R.J. Stapes surgery in osteogenesis imperfecta: Analysis of postoperative hearing loss. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991;100:120-130.

37. Garretsen T.J.T.M., Cremers C.W.R.J. Ear surgery in osteogenesis imperfecta. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;116:317-323.

38. Vincent R., Gratacap B., Oates J., Sperling N. Stapedotomy in osteogenesis imperfecta: A prospective study of 23 consecutive cases. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26:859-865.

39. Inserra M.M., Mason T.P., Yoon P.J., Roberson J.B.Jr. Partial promontory technique in stapedotomy cases with narrow niche. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:443-446.

40. Stidham K., Roberson J.B.Jr. Cochlear hook anatomy: Evaluation of the spatial relationship of the basal cochlear duct to middle ear landmarks. Acta Otolaryngol. 2000;119:773-777.

41. Leek J.H. An anomalous facial nerve: The otologist’s albatross. Laryngoscope. 1974;84:1535-1544.

42. Willis R. Conductive deafness due to malplacement of the seventh nerve. J Otolaryngol. 1977;6:1-4.

43. Gherini S.G., Horn K.L., Bowman C.A., et al. Small fenestra stapedotomy using a fiberoptic hand-held argon laser in obliterative otosclerosis. Laryngoscope. 1990;100:1276-1282.

44. Derlacki E.L. Revision stapes surgery: Problems with some solutions. Laryngoscope. 1985;95:1047-1053.

45. Farrior D. Abstruse complications of stapes surgery: Diagnosis and treatment. In: Henry Ford Hospital International Symposium on Otosclerosis. Chicago: Little, Brown; 1962:509-521.

46. Glasscock M.E. The stapes gusher. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1973;98:82-91.

47. Brodie H.A. Prophylactic antibiotics for post-traumatic cerebrospinal fluid fistulae: A meta-analysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:749-752.

48. Radeloff A., Unkelbach M.H., Tillein J., et al. Impact of intrascalar blood on hearing. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:58-62.

49. Majoras M. Electronystagmography during stapedectomy. Int Surg. 1967;47:323-327.

50. Gristwood R.E. Acute otitis media following the stapedectomy operation. J Laryngol Otol. 1966;80:55-60.

51. Brown J.S. Meningitis following stapes surgery: The pathway of spread to the intracranial cavity. Laryngoscope. 1967;77:1295-1303.

52. Snyder B.D. Delayed meningitis following stapes surgery. Arch Neurol. 1979;36:174-175.

53. Harrill W.C., Jenkins H.A., Coker N.J. Barotrauma after stapes surgery: A survey of recommended restrictions and clinical experiences. Am J Otol. 1996;17:835-846.

54. Althaus S.R., House H.P. Delayed post-stapedectomy facial paralysis: A report of five cases. Laryngoscope. 1973;83:1234-1240.

55. Matthisen J. Phonophobia after stapedectomy. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh). 1969;68:73-77.

56. Bracewell A. Diplacusis binauralis—a complication of stapedectomy. J Laryngol Otol. 1966;80:55-60.

57. Cody T., Baker H. Otosclerosis: Vestibular symptoms and sensorineural hearing loss. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1978;87:778-796.

58. Das T.K., Susheela A.K., Gupto I.P., et al. Toxic effects of chronic fluoride ingestion on the upper gastrointestinal tract. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1994;18:194-199.

59. Cole J.M., Bartels L.J., Beresny G.M. Long-term effect of otosclerosis on bone conduction. Laryngoscope. 1979;89:1053-1060.

60. Vartiainen E., Virtaniemi J., Kemppainen M., et al. Hearing levels of patients with otosclerosis ten years after stapedectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;108:251-255.

61. Linthicum F.H. Correlations of sensorineural hearing impairment and otosclerosis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1966;75:512-524.

62. Balle V., Linthicum F.H.Jr. Proven cochlear otosclerosis: Sensorineural without conductive hearing loss. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1984;93:105-111.

63. Causse J.R., Uriel J., Berges J., et al. The enzymatic mechanism of the otospongiotic disease and NaF action on the enzymatic balance. Am J Otol. 1982;3:297-314.

64. Causse J.R., Causse J.B., Uriel J., et al. Sodium fluoride therapy. Am J Otol. 1993;14:482-490.

65. Forquer B.D., Linthicum F.H., Bennett C. Sodium fluoride: Effectiveness of treatment for cochlear otosclerosis. Am J Otol. 1986;7:121-125.

66. Bretlau P., Causse J., Causse J.B., et al. Otospongiosis and sodium fluoride: A blind experimental and clinical evaluation of the effect of sodium fluoride treatment in patients with otospongiosis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1985;94:103-107.

67. Bretlau P., Salomon G., Johnsen N.J., et al. Otospongiosis and sodium fluoride: A clinical double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sodium fluoride in otospongiosis. Am J Otol. 1989;10:2-20.

68. Shambaugh G.E.Jr., Scott A. Sodium fluoride for arrest of otosclerosis. Arch Otolaryngol. 1964;80:263-270.

69. Linthicum F.H., House H.P., Althaus S.R. The effect of sodium fluoride on otosclerotic activity as determined by strontium 85. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1973;82:609-613.

70. Pedersen C.B., Felding J.U. Stapes surgery: Complications and airway infection. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991;100:607-611.

71. Sheehy J.L., Nelson R.A., House H.P. Revision stapedectomy: A review of 258 cases. Laryngoscope. 1981;91:43-51.

72. Feldman B.A., Schuknecht H.F. Experiences with revision stapedectomy procedures. Laryngoscope. 1970;80:1281-1291.

73. Glasscock M.E., McKennan K.X., Levine S.C. Revision stapedectomy surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;96:141-148.

74. Marshall A.H., Fanning N., Symons S., et al. Cochlear implantation in cochlear otosclerosis. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1728-1733.

75. Pearman K., Dawes J.D.K. Post-stapedectomy conductive deafness and results of revision surgery. J Laryngol Otol. 1982;96:405-410.

76. Farrior J., Sutherland A. Revision stapes surgery. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:1155-1161.

77. McGee T.M. The loose-wire syndrome. Laryngoscope. 1981;91:1478-1483.

78. Moon C.N. Perilymphatic fistulas complicating the stapedectomy operation: A review of 49 cases. Laryngoscope. 1970;80:515-535.

79. Lippy W.H., Schuring A.G. Stapedectomy revision following sensorineural hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1984;92:580-582.

80. Fenton J.E., Turner J., Shirazi A., et al. Post-stapedectomy reparative granuloma: A misnomer. J Laryngol Otol. 1996;110:185-188.

81. Goebel J.A., Jacob A. Use of Mimix hydroxyapatite bone cement in ossicular reconstruction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132:727-734.

82. Seicshnaydre M.A., Sismanis A., Hughes G.B. Update of reparative granuloma: Survey of the American Otological Society and the American Neurotology Society. Am J Otol. 1994;15:155-160.

83. Von Haacke N.P. Cholesteatoma following stapedectomy. J Laryngol Otol. 1987;101:708-710.

84. Benecke J.E., Gadre A.K., Linthicum F.H. Chondrogenic potential of tragal perichondrium: A cause of hearing loss following stapedectomy. Laryngoscope. 1990;100:1292-1293.

85. Pedersen C.B. Revision surgery in otosclerosis: Operative findings in 186 patients. Clin Otolaryngol. 1994;19:446-450.

86. Pedersen C.B. Revision surgery in otosclerosis—an investigation of the factors which influence the hearing result. Clin Otolaryngol. 1996;21:385-388.

87. Prasad S., Kamerer D.B. Results of revision stapedectomy for conductive hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;109:742-747.

88. Crabtree J.A., Britton B.H., Powers W.H. An evaluation of revision stapes surgery. Laryngoscope. 1980;90:224-229.

89. Wiet R.J., Kubek D.C., Lemberg P., et al. A meta-analysis review of revision stapes surgery with argon laser: Effectiveness and safety. Am J Otol. 1997;18:166-171.

90. Hammerschlag P.E., Fishman A., Scheer A.A. A review of 308 cases of revision stapedectomy. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:1794-1800.