Chapter 37 Autologous gluteal augmentation with mid-pedicle superior pole perforator flaps

• Brief review of surgical techniques for gluteal augmentation.

• Explanation of the details of our surgical technique designed to provide autologous gluteal augmentation.

• Highlighting of common errors and pitfalls of this surgical technique and how to avoid them.

• Highlighting of possible surgical complications and how to approach them.

• Highlighting the methods of assessment of gluteal projection after gluteal augmentation with mid-pedicle superior pole perforator flaps.

Introduction

Gluteal augmentation has become increasingly common due to a rise in bariatric surgery in North America as well as because of ingrained cultural ideals, combined with increasingly easy access to esthetic surgery in South America. Projection of the gluteal region has become a sign of a well-sculpted body, and consequently, is a goal of individuals who seek body contouring procedures. While Bartels et al were the first to report silicone gluteal augmentation in 1969,1 more recently, numerous autologous procedures have been developed, including fat grafting, dermal-fat grafting, and, more recently, dermal-fat flaps.2–10 Indeed, fat grafting plays an important role in gluteal augmentation in selected patients with low complication rates; however, it may not work well in patients after weight loss. Excess of skin combined with muscle hypotonia and skin flaccidity in patients after significant weight loss may contraindicate fat grafting procedures. For these patients, Agris,11 based on the work of Pitanguy,12,13 proposed the use of dermal-fat suspension flaps for thigh and buttock lifts. In addition, Gonzalez-Ulloa,14 Guerrerosantos15 and many others have proposed several types of adipocutaneous flaps to improve contours in this region.16,17

Flaps proposed in the past have provided little projection to the upper gluteal region and are based on de-epithelialization of the gluteal region commonly discarded after major body contouring and circumferential body lift procedures. Pascal and Le Louarn18 should be credited for noticing the importance of preserving the de-epithelialized upper excess of soft tissue to better shape the gluteal region, avoiding the hollow aspect of the upper pole seen in patients with a lack of gluteal muscle tone. Progressive understanding of perforator anatomy in the gluteal region allows surgeons to respond appropriately to patient complaints and desires.19 The superior gluteal region, which is either discarded in body contouring procedures or simply de-epithelialized, can now be used to offer additional augmentation to the gluteal sagittal projection, treating the ptotic and sagging buttock. The edges of the superior gluteal dermal-fat flaps can be rotated to the midline to add volume to the gluteal region.

Preoperative Preparation

With the patient in a standing position, we pull the excess skin cephalad with our open hand on the hip region. Then, beginning about 4 cm above the coccyx, a line is marked in the direction of the iliac region, usually a little bit below the anterior iliac spine. This line will join a classic abdominoplasty scar at some position where it curves anterolaterally. When an abdominal scar does not exist, the line is marked on the projected scar of a supposed abdominoplasty. With the fingers pinching the skin at the lumbar region, we determine the amount of skin excess to be resected. Next, on the lumbar region, we mark a second line at the superior aspect of the skin excess. The second line is initially parallel to the first, but then continues laterally to the upper anterior iliac spine to be joined with the first line at either the classic abdominal scar or its supposed projected position. These markings result in a long fusiform-shaped area between two points, both beginning and finishing inferior to the anterior superior iliac spine (Fig. 37.1). The direction of this line depends on the skin excess and is usually asymmetric. Occasionally, the union point of these two lines extends as far as the hemiclavicular line or even into the pubic region.

Surgical Technique

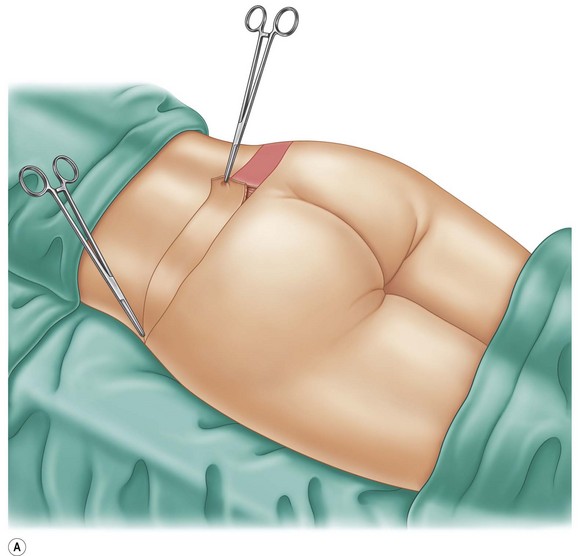

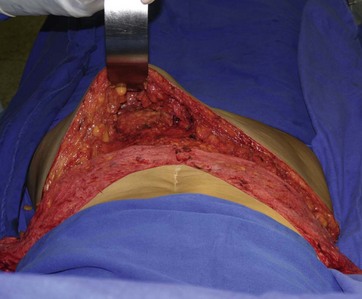

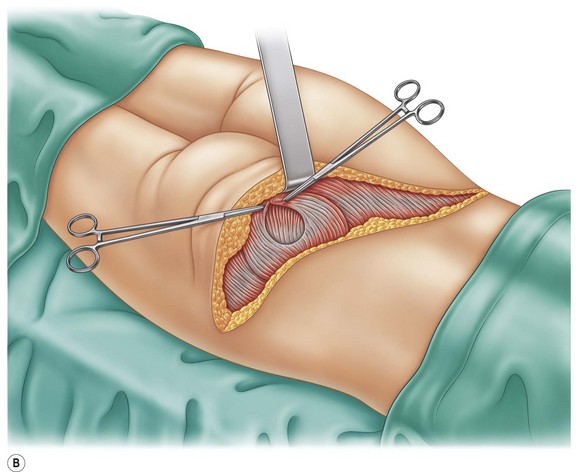

Under general or epidural anesthesia, the patient is placed in a ventral decubitus position. The fusiform-shaped area is de-epithelialized, and an incision is made along the inferior edge of this area to the gluteal muscle fascia and then in a direction near the gluteal fold, producing an adipocutaneous flap (a pocket to receive the dermal-fat rotation flaps) (Figs 37.2 and 37.3). Next, incisions are made along the superior edge of the fusiform-shaped area down to the lumbar–hip musculature aponeurosis. A sagittal incision along the midline of the fusiform-shaped area is then made. The medial and lateral segments of the dermal-fat flaps are undermined, maintaining a large pedicle in the region corresponding to the position of the gluteal perforator’s vessels. The two segments are rotated and either sutured together in the muscle plane or alternatively fixed with a Reverdin needle, and transcutaneous fixation sutures are tied to gauze and buttoned over the transfixed skin near the gluteal region (Fig. 37.4). The inferior adipocutaneous flaps are brought over the dermal-fat flaps in an upward direction and sutured to the upper lumbar–hip skin border using biplanar wound closure. The same procedure is performed on the contralateral side. We also perform numerous quilting sutures to fix the gluteal skin flaps to the aponeurosis after rotation of the dermal-fat flaps. This maneuver has proven to be efficient in diminishing the seroma rate in abdominoplasty and has similar effects in the gluteal region. Another maneuver used during the undermining of the dermal-fat skin flaps is to leave a fat layer over the gluteal fascia to decrease seroma formation. These technical details have been responsible for decreasing the duration of drainage.

In cases in which the preoperative marking lines reach the anterior abdominal wall, the operation is begun with the patient in the dorsal decubitus position, and after rotation of the two anterior dermal flaps to the back, the patient is changed to the ventral decubitus position, and the lumbar-hip dermal-fat flaps are fashioned. Two large suction drains are placed in each side at the end of both the dermal-fat flap insertion and adipocutaneous flap rotation, and the patient is kept in the hospital in either the ventral or lateral decubitus position until at least the first postoperative day. Overall, patients were satisfied with the surgical outcomes as well as the longevity of the new shape of the gluteal region achieved with this operation (Figs 37.5–37.11).

Optimizing Outcomes

Understanding the Geometric Shape of the Gluteal Region

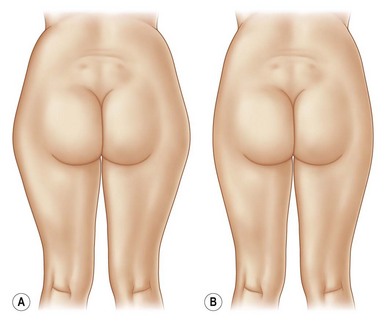

The beauty of the gluteal region involves the sagittal projection associated with the relative volume of and satisfactory fat distribution along the lower limbs. Several authors have developed a comprehensive classification system for the ideal fat distribution in the posterior region.20–22 In patients with weight loss, skin flaccidity, and muscle hypotonia, we favor augmentation of the upper gluteal pole only. Long-term follow up has demonstrated its benefits (Fig. 37.12).

Understanding the Relevance of the Upper Gluteal Pole Perforator Anatomy

In 2003, criticism was raised during the early conceptualization and development of dermal-fat flaps for autologous gluteal augmentation.23 The main concern was the perfusion of the flaps and the potential chance of ischemia and necrosis during the follow up period. Interestingly, Kankaya and co-workers classified the gluteal region into three vascular zones based on an anatomic study. This group found (in a cadaver study) that the superior gluteal zone contained 48.5% of perforators, whereas the central gluteal zone was noted to be the most poorly vascularized region.24 These findings corroborate our empirical and initial concern about the lack of gluteal perforators in the medial aspect, which may jeopardize dermal-fat flaps based on pedicles from this zone. For this reason, we always favor superior pole gluteal augmentation rather than mid-level gluteal augmentation. Our concern about the vascular supply of the dermal-fat flap has driven our choice of the superior pole mid-pedicle flaps.

Complications and Their Management

During our 7-year experience using this technique, we had only one patient with low perfusion of the skin flaps. Infection, even when proper antiseptic technique is performed, can be related to lack of blood supply and it was never seen in our patients. In order to avoid complications, procedures combined with gluteoplasty augmentation are rarely done. Liposuction of the lateral thighs might be performed to improve the shape of the gluteal region in selective patients (Fig. 37.13).

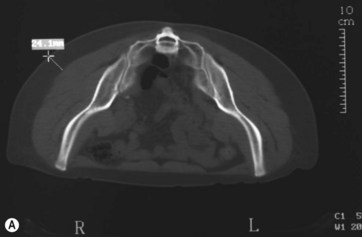

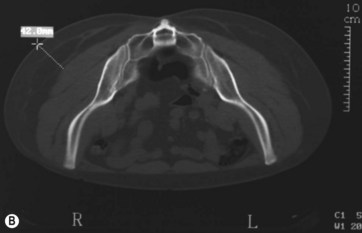

Assessment of Gluteal Projection and Possible Dermal-Fat Complications and Calcifications

Babuccu was the first to describe anthropometric measurements for gluteal morphology analysis after time, aging, and weight gain.25,26 Radiographic and anthropometrical tools, however, have not been routinely used for surgical outcome validation.

A simple equation was proposed to quantify the postoperative gluteal projection:

The overall conclusion of this study is that the goniometer method is preferred, since it shows less variability in each measurement (both before and after surgery). These measurements (both before and after surgery) correlated with each other and were equal to those measurements obtained using the CT scan method, which is much more expensive.27 We did not observe calcifications and/or any sign of fat necrosis during the postoperative period. We conclude that the goniometer is a simple and reliable device for measuring gluteal projections after any type of gluteoplasty technique (Fig. 37.14).

1 Bartels RJ, O’Malley JE, Douglas WM, et al. An unusual use of the Cronin breast prosthesis. Case report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1969;44:500–509.

2 Cardenas-Camarena L, Lacouture AM, Tobar-Losada A. Combined gluteoplasty: liposuction and lipoinjection. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:1524–1531.

3 Peren PA, Gomez JB, Guerrerosantos J, et al. Gluteus augmentation with fat grafting. Aesth Plast Surg. 2000;24:412–417.

4 Raposo-Amaral CE, Cetrulo CL, Jr., Guidi M de C, et al. Augmentation gluteoplasty using dermal fat autografting from the lower abdomen. Aesth Surg J. 2006;26:290–298.

5 Coban YK, Uzel M, Celik M. Correction of buttock ptosis with anchoring deepithelialized skin flaps. Aesth Plast Surg. 2004;28:116–119.

6 Rhode CE, Gerut ZE. Remodeling bodylift with high lateral tension. Aesth Surg J. 2005;25:576–582.

7 Sozer SO, Agullo FJ, Wolf C. Autoprosthesis buttock augmentation during lower body lift. Aesth Plast Surg. 2005;29:133–137.

8 Centeno RF. Autologous gluteal augmentation with circumferential body lift in the massive weight loss and aesthetic patient. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33:479–496.

9 Raposo-Amaral CE, Cetrulo CL, Jr., Guidi M de C, et al. Bilateral lumbar hip dermal fat rotation flaps: a novel technique for autologous augmentation gluteoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:1781–1788.

10 Colwell AS, Borud LJ. Autologous gluteal augmentation after massive weight loss: aesthetic analysis and role of the superior gluteal artery perforator flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:345–356.

11 Agris J. Use of dermal-fat suspension flaps for thigh and buttock lifts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;59:817–822.

12 Pitanguy I. Trochanteric lipodystrophy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1964;34:280–286.

13 Pitanguy I. Surgical reduction of the abdomen, thighs and buttocks. Surg Clin N Am. 1971;51:479–489.

14 Gonzalez-Ulloa M. Gluteoplasty: a ten-year report. Aesth Plast Surg. 1991;15:85–91.

15 Guerrerosantos J. Secondary hip-buttock-thigh plasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1984;11(3):491–503.

16 Gonzalez M, Guerrerosantos J. Deep planed torso-abdominoplasty combined with buttocks pexy. Aesth Plast Surg. 1997;21:245–253.

17 Regnault P, Daniel R. Secondary thigh-buttock deformities after classical techniques prevention and treatment. Clin Plast Surg. 1984;11(3):505–516.

18 Pascal JF, Le Louarn C. Remodeling bodylift with high lateral tension. Aesth Plast Surg. 2002;26:223–230.

19 Taylor GI. The angiosomes of the body and their supply to perforator flaps. Clin Plast Surg. 2003;30:331–342.

20 Cuenca-Guerra R, Quezada J. What makes buttocks beautiful? A review and classification of the determinants of gluteal beauty and the surgical techniques to achieve them. Aesth Plast Surg. 2004;28:340–347.

21 Cuenca-Guerra R, Lugo-Beltran I. Beautiful buttocks: Characteristics and surgical techniques. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33:321–332.

22 Mendieta CG. Classification system for gluteal evaluation. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33:333–346.

23 Raposo-Amaral CE, et al. Gluteal augmentation with dermal-fat flaps. Awarded Ivo Pitanguy-Ethicon Prize for best paper presentation at the 41st Annual Brazilian Congress of Plastic Surgery, in Florianópolis, Brazil, November 19–22, 2004.

24 Kankaya Y, Ulusoy MG, Oruç M, et al. Perforating arteries of gluteal region. Anatomic study. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;56:409–412.

25 Babuccu O, Kargi E, Hosnuter M, et al. Morphology of the gluteal region in the female population 5 to 83 years of age. Aesth Plast Surg. 2004;28:405–411.

26 Babuccu O, Gozil R, Ozmen S, et al. Gluteal region morphology: the effect of the weight gain and aging. Aesth Plast Surg. 2002;26:130–133.

27 Raposo-Amaral CE, Ferreira DM, Warren SM, et al. Quantifying augmentation gluteoplasty outcomes: a comparison of three instruments used to measure gluteal projection. Aesth Plast Surg. 2008;32:333–338.