CHAPTER 42 Autologous Flap Use in Breast Reshaping after Massive Weight Loss

Key Points

Introduction

The degree of change in the breast shape and form depends on several factors that include:

Breast Reshaping Strategies

The aim of body contouring surgery is correction of the lost shape and form. In the MWL patient a thorough understanding of the deformity and the patient’s desires need appreciation. Many MWL patients display loss of volume from their breasts. However, depending on their genetic make up, race, highest weight, and the lost weight, the amount of fatty and glandular volume lost from each breast may vary. For some, the breasts will be completely deflated whereas others will still have significant macromastia. In between these extremes, there are variable breast shapes and sizes. For those with existing macromastia and ptosis, we commonly perform a Wise-pattern reduction and mastopexy or dermal bra suspension technique as has been described by Rubin and Agha-Mohammadi.1 For others who require breast volume, we now commonly employ the excess local tissue for autologous augmentation.

Autologous Breast Augmentation

Operative technique – commonly used autologous flaps

Lateral thoracic flap

The lateral thoracic flap lies in the thorax between the anterior and posterior axillary lines. In MWL patients, this region is often prominent and lax. Furthermore, the breast tail of Spence loses its demarcation with the lateral thoracic region and flows as a transverse fold in continuity with the back. For those patients who have significant circumferential laxity of the chest with mild vertical back excess, a lateral thoracic flap can be developed as part of a vertical thoracoplasty. In combination with a reverse abdominoplasty, we refer to this flap as the sickle modification of the spiral flap.2 The excess lateral thoracic tissue can be relatively extended to span over the thorax to the back. It represents all the tissue between the anterior axillary line and the posterior axillary line, which is further displaced posteriorly with weight gain and loss.

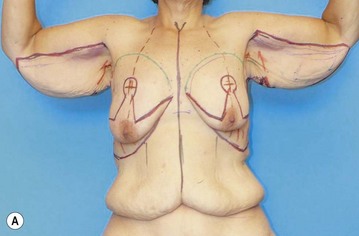

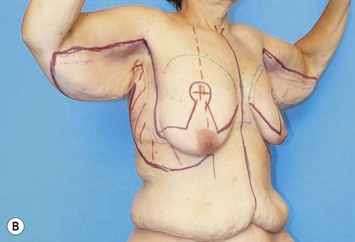

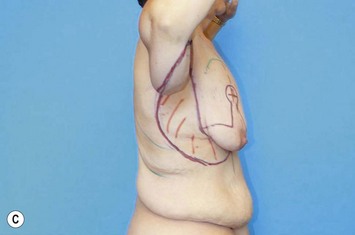

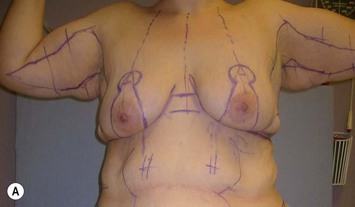

The preoperative markings are completed with the patient in the standing upright position. All anatomic landmarks are identified and marked (sternal notch, midclavicular point, meridian line, nipple–areola position, IMF, and the breast tail/lateral thoracic demarcation). The posterior marking of the vertical thoracoplasty is then drawn by pinching and advancing the circumferential excess up to the anterior axillary line (Fig. 42.1).

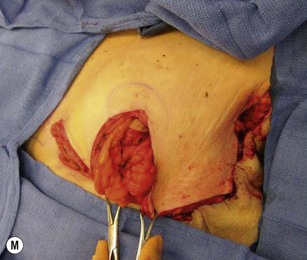

The flap can be approached in two ways. It can be developed in a vertical manner by incising over the anterior and posterior axillary lines toward the lateral thoracic fascia. Roughly parallel vertical incisions are made through to the lateral border of the pectoralis major muscle and the anterior border of the latissimus dorsi muscle. The flap is then elevated from axilla along the anterior border of the latissimus muscle over the serratus muscle fascia towards its continuation with the epigastric flap. The lateral thoracic flap is then rotated medially and spiraled into a submammary pocket. Alternatively, the flap can be elevated in continuity with the lateral breast tissue. The vertical incision is made over the posterior marking along the anterior latissimus dorsi border. The flap is released proximally at the axilla. It is then raised by undermining the lateral thoracic tissue from the posterior incision over the lateral thoracic fascia toward the breast tail and up to the anterior axillary line. The epigastric and lateral thoracic flap crescent is undermined cautiously toward the breast parenchyma, leaving major perforator vessels intact when possible. The flaps maintain their blood supply via perforators through the serratus muscle and the breast parenchyma. They are then secured in place via absorbable sutures (interrupted 2-0 Vicryl) to create a breast mound (Fig. 42.2). The IMF is then reconstructed as for the epigastric flap. The back tissue is then advanced all the way to the anterior axillary line and is secured to the underlying serratus muscle using large bites of non-absorbable sutures (#0 Surgilon). The breast tissue is then approximated to the posterior thoracic tissue via interrupted Vicryl sutures. In this manner, the breast tail/lateral thoracic demarcation is reconstructed and the breast mobility and laxity preserved (Figs 42.3 and 42.4).

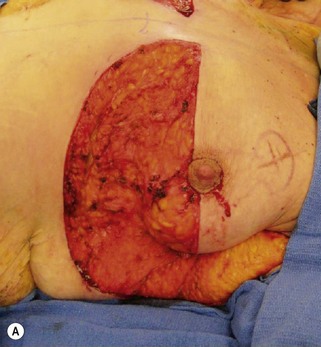

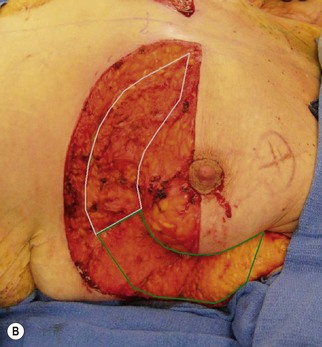

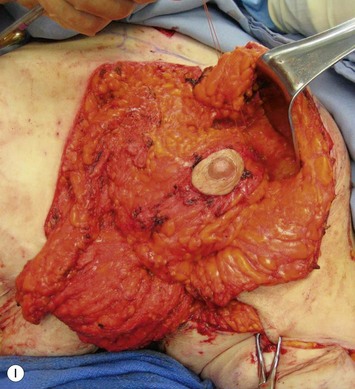

Fig. 42.2 Operative sequence of breast reshaping with epigastric and lateral thoracic flaps of the same patient as in Figure 42.1.

Courtesy of Siamak Agha-Mohammadi.

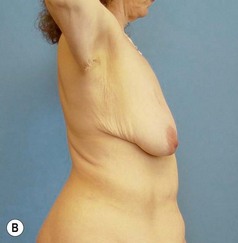

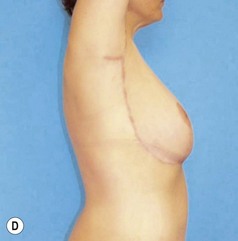

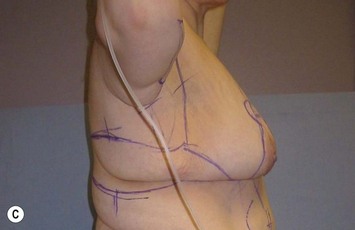

Fig. 42.3 A Pre-operative picture of the MWL patient in Figures 42.1 and 42.2 presenting with breast asymmetry, upper body laxity and arm laxity. B Postoperative picture of the same patient at 2 weeks. C, D Postoperative pictures of the same patient at 9 months. Patient had an L-brachioplasty, J-thoracoplasty, reverse abdominoplasty and asymmetrical breast reshaping with sickle modification of Spiral flap.

Courtesy of Siamak Agha-Mohammadi.

Spiral flap

For those patients who have moderate-to-significant degree of excess upper thoracic and back tissue in a vertical direction, the spiral flap will provide the most ample local tissue for autologous breast augmentation. The flap corresponds to the upper back fold that extends laterally over the chest and back and is typically excessive in those patients who have significant vertical upper torso laxity. The spiral flap takes advantage of the excess back tissue as a posterior thoracic flap in combination with the epigastric and lateral thoracic flaps.3 Use of this flap for autologous augmentation addresses both the issue of excess upper back laxity and breast volume loss. This dermoadipose flap is supplied through the posterior branches of intercostal vessels and branches derived from lateral thoracic fascia.

The spiral flap is particularly suited for those patients who have significant vertical laxity of the upper torso and significant loss of breast volume. The former characteristic typically presents as bilateral cascading lateral chest and back rolls. In these patients, the spiral flap is often combined with a Wise-pattern mastopexy. Similar to the lateral thoracic and epigastric flaps, the preoperative markings are completed with the patient in the standing upright position. All anatomic landmarks are identified and marked (sternal notch, midclavicular point, meridian line, nipple–areola position, and inframammary fold, anticipated new IMF position). The patient’s upper back roll in line with the breast tail is marked over the lateral chest and the back for excision. The markings extend from the midaxillary line transversely and converge medially as they approach the midback. The lower line is in continuity with the IMF or the lower incision of the reverse abdominoplasty markings. The upper marking is determined by pinching the excess back tissue while converging on the lower markings of the Wise-pattern mastopexy (Fig. 42.5). The size of the upper back roll is reflective of the volume of augmentation. The marked upper back roll is cut to the muscle fascia and then de-epithelialized from its apex towards its base at the midaxillary line while the patient is in a prone position. This defines the boundaries of the spiral flap.

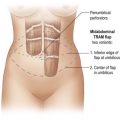

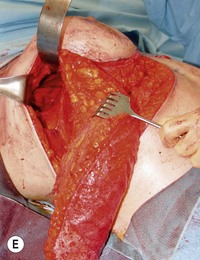

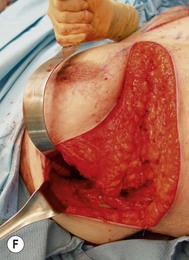

The flap is then elevated with the fascia of the underlying latissimus dorsi muscle toward its base. Dissection stops just beyond the anterior border. The base of the flap is left intact in continuity with the breast tail over the lateral thoracic fascia. After the donor site is closed in two layers, the patient is turned supine. The upper incision is extended up to the anterior axillary line. A submammary pocket is meticulously created as a crescent under the upper aspect of the breast mound and extended medially to the medial apex. A large pocket should be avoided since it will result in a flat, pancake-shaped breast. The apex of the flap is then spiraled through the submammary pocket and is pulled medially at the medial edge. The flap tip is then sutured in place at the medial edge to the underlying pectoralis major fascia over the fourth or fifth costochondrium (Fig. 42.6).

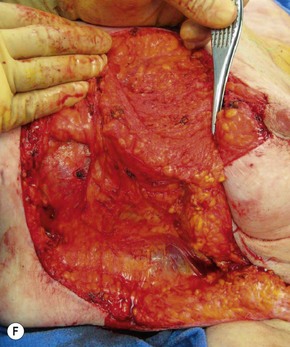

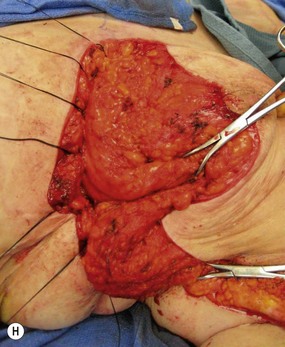

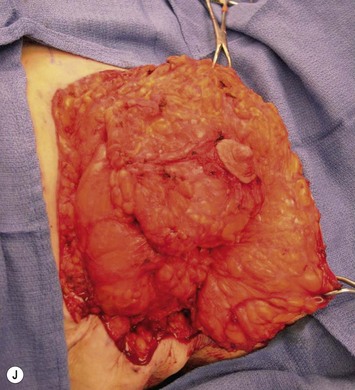

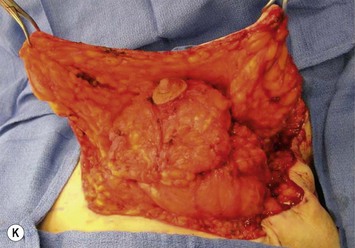

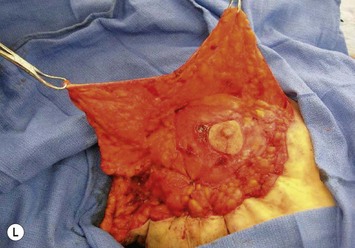

Fig. 42.6 Operative sequence of breast reshaping with the Spiral flap.

Courtesy of Dennis J. Hurwitz.

Our experience with the use of this technique in bariatric patients has proved aesthetically pleasing in reconstructing the breast mound and correcting the upper torso deformity (Fig. 42.7).

Postoperative Care

Postoperative care starts during the preoperative assessment of the MWL patient. All patients are cleared medically for the procedure, with chest X-ray and ECG and regular laboratory parameters as needed. In addition, we pay special attention to the patients’ nutritional deficiencies and obtain laboratory tests for total protein, albumin, prealbumin, vitamin A, vitamin B12, folate, and homocystine levels. All patients are placed on a perioperative nutritional supplement designed specifically for enhanced recovery after surgery.4 Patients are encouraged to donate autologous blood when possible for larger cases. There is no special postoperative care for breast reshaping than for that treating the whole body contouring patient. We do not usually use drains with these procedures. Patients are typically placed in a lightly compressive breast dressing for about 2 weeks. Heavy lifting and exercise is prohibited for about 4 weeks. Special attention is paid to appropriate hydration, transfusion, ambulation and use of sequential pneumatic compression stockings.

Discussion

The breast deflation, Cooper’s ligament laxity, loss of skin elasticity, and alteration of the three-dimensional breast connective tissue ultrastructure results in variable degrees of glandular and nipple areola ptosis. In MWL patients, the underlying deformities of the breasts are deflation and severe ptosis. Breast ptosis, as described by Regnault,5 is due to a discrepancy between breast volume and the overlying skin envelope. A variety of procedures have been employed in plastic surgery to rejuvenate the aging ptotic breast population. Surgical correction consists of increasing breast volume, reducing the skin envelope, or a combination of both in the form of an augmentation/mastopexy.6–10 Many of the described techniques are best suited for small to medium sized breasts of the aging population, including Benelli’s periareolar incision,11 Regnault’s B technique,9 cirumvertical incision,12 Lejour’s vertical incision,13 and Wise-pattern incision procedures.14 Even though these procedures produce enhanced projection of the assembled breasts, the younger postbariatric patient with MWL poses new challenges that require an alternative approach.

With massive weight gain both upper and lower body accumulate fat depositions that are not only dependent on the amount of calorie intake, but also determined by age, gender, and genetic predispositions of the patients. In addition, the patient’s tissue quality and zones of adherence play an important role in confining the local fatty depositions. In the upper body, hypertrophy of the fatty tissue results in a three-dimensional expansion of the subcutaneous tissue layer of the upper torso. This results in stretching of the superficial fascial system and dermal breakage of skin to a varying degree. Consequently, zones of adherence and demarcations become loose and the skin develops striae. MWL often results in dissolution of fat in the subcutaneous layer. Hence, the subcutaneous tissue becomes loose, deflated and sagging due to irreversible loss of the superficial fascial system and dermal elasticity. In the upper body, the deflated tissue appears as cascading rolls that extend from the sternum to the vertebral column.15 The breast deformity is also complex. The patients not only have severely ptotic breasts, but also the breast volume is unevenly lost resulting in flat pendulous breasts. Furthermore, the remaining overstretched breast skin is often significantly excessive and is of poor quality due to many cycles of expansion and reduction. Often, these patients require complete reshaping of their breasts to a rounder form as well as a breast lift. Postbariatric patients typically present with variable and asymmetric degrees of volume loss from each breast. The breast reshaping procedure includes some form of mastopexy with or without breast reduction or breast augmentation; depending on the volume lost and the patient’s desire.

1 Rubin JP, Agha-Mohammadi S. Approach to breast after weight loss. In: Rubin JP, Matasasso A, editors. Aesthetic surgery after massive weight loss. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:37-48.

2 Hurwitz DJ, Agha-Mohammadi S. Breast surgery in the massive weight-loss patient. in Procedures in Reconstructive Surgery series edited by Evans G. Nahabedian MY, editor. Cosmetic and reconstructive breast surgery. London, UK: Thieme Medical Publishers. 2009: 183-196.

3 Hurwitz DJ, Agha-Mohammadi S. Postbariatric surgery breast reshaping: the spiral flap. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;56(5):481-486.

4 Agha-Mohammadi S, Hurwitz DJ. Nutritional deficiency of post-bariatric body contouring patients: what every plastic surgeon should know? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122(2):604-613.

5 Regnault P. Breast ptosis. Definition and treatment. Clin Plast Surg. 1976;3(2):193-203.

6 Davis GM, Ringler SL, Short K, Sherrick D, Bengtson BP. Reduction mammaplasty: Long-term efficacy, morbidity and patient satisfaction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:1106.

7 Courtiss EH, Goldwyn RM. Reduction mammaplasty by the inferior pedicle technique: an alternative to free nipple and areola grafting for severe macromastia or extreme ptosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;59:500.

8 Georgiade GS, Riefkohl RE, Georgiade N. Inferior pyramidal technique. In: Goldwyn RM, editor. Reduction mammaplasty. Boston: Little, Brown; 1990:268-275.

9 Regnault P. Breast reduction: B technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;65:840.

10 Lassus C. A technique for breast reduction. Int Surg. 1970;53:69-72.

11 Benelli L. A new periareolar mammaplasty: The ‘round block’ technique. Aesth Plast Surg. 1990;14:93.

12 Mottura AA. Circumvertical reduction mammaplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2002;29(3):393-399.

13 Lejour M. Vertical mammaplasty and liposuction of the breast. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;94:100.

14 Wise RJ. A preliminary report on a method of planning the mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1956;17:365-370.

15 Agha-Mohammadi S, Hurwitz DJ. Management of upper abdominal laxity after massive weight loss: reverse abdominoplasty and intramammary fold reconstruction. Aesth Plast Surg. 2009. (in preparation)