Chapter 35 Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation

INTRODUCTION

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and meniscus injuries are often combined with articular cartilage injuries, in which the cartilage injury is the most serious and most difficult to treat in the end. Noyes and coworkers18,19 and Shelbourne and associates24 found that acute and chronic ACL injuries were associated with articular cartilage injuries in 40% to 70% of knees. There are reports that in cases of meniscus injury, 40% to 50% of patients also have cartilage damage.25 Hjelle and colleagues11 reported on 1000 consecutive patients with symptoms requiring arthroscopy. Chondral or osteochondral lesions of any type were found in 61% of the patients. Curl and coworkers5 found that in 31,516 patients who underwent arthroscopy, 63% had a cartilage lesion and 19% had an Outerbridge grade IV cartilage lesion. Bone bruises have been reported in acute knee injuries12 and in combination with ACL injuries in 80%.17 The damage to the trabecular bone may heal, but the overlying cartilage may degrade over time.

INDICATIONS

The recognition of serious articular cartilage injuries, including bipolar lesions in young and middle-aged individuals, has along with increased experience widened the indications for ACI (Fig. 35-1).

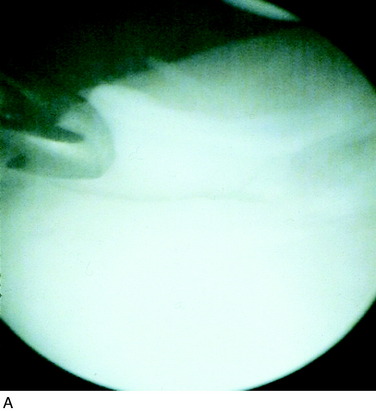

INTRAOPERATIVE EVALUATION

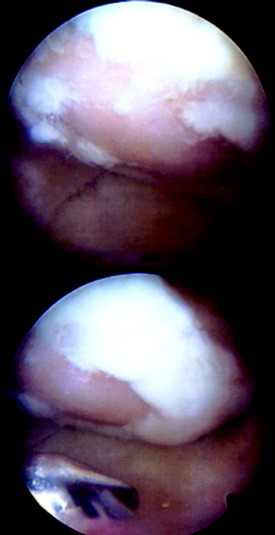

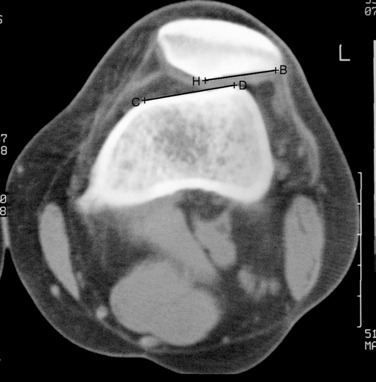

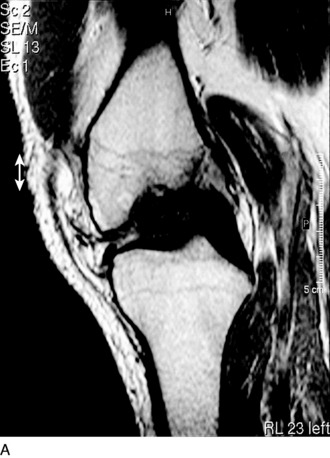

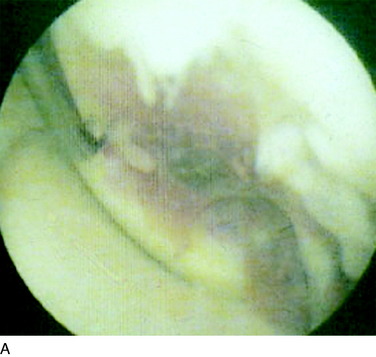

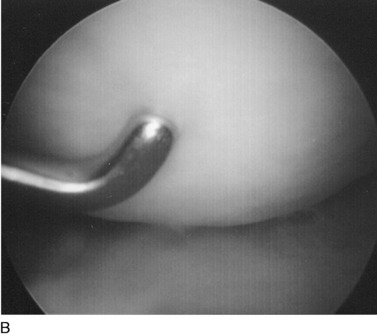

During the first-stage arthroscopy, knee stability is reassessed under anesthesia. The lesion is examined to decide whether it meets the indications for ACI. The lesion should be surrounded by healthy cartilage (but uncontainment is not a contraindication) and the opposing articular surface should be undamaged or have only minor superficial cartilage injury (Fig. 35-2). All intra-articular structures should be examined. The location, size, and depth should be noted using, for instance, the ICRS Knee Evaluation Package. Slices of cartilage with subchondral bone are harvested with a curet. The recommended harvest sites are the medial and lateral proximal rim of the femoral trochlea and the lateral aspect of the intercondylar notch in the knee joint. In more than 1400 patients who have had cartilage removed from the proximal medial trochlea for cell culturing, no complications or late symptoms have occurred from the donor site area. An optimal harvesting of cartilage is of great importance for the success of the cell culturing. Optimal cell quality is necessary for a successful result of this procedure and should be performed according to good laboratory practice or national regulations if present.

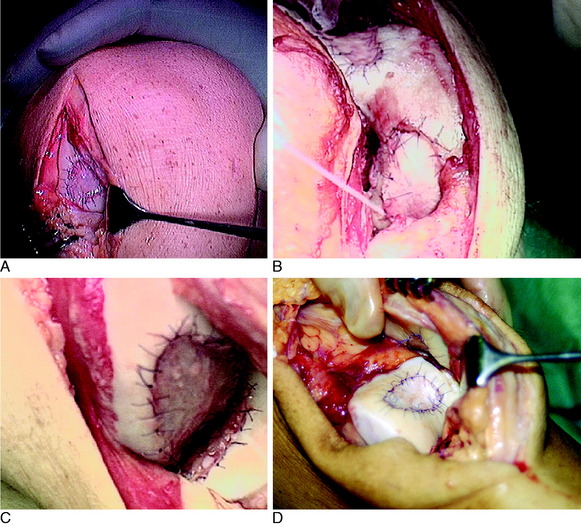

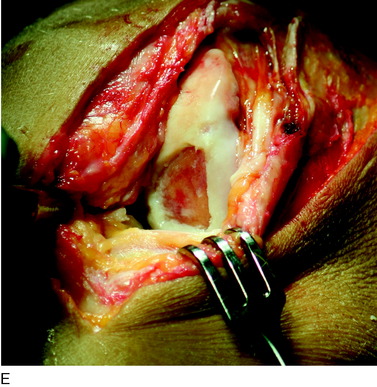

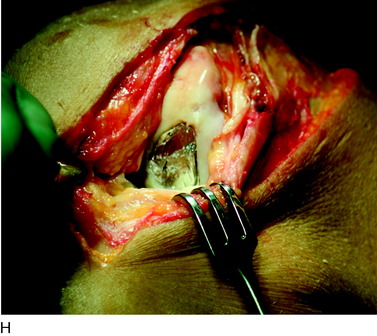

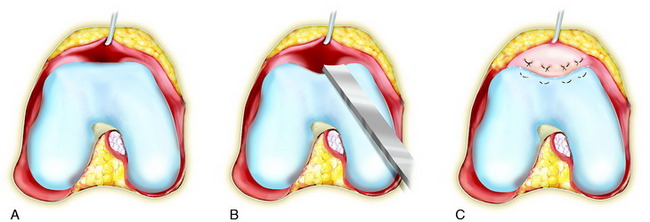

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE

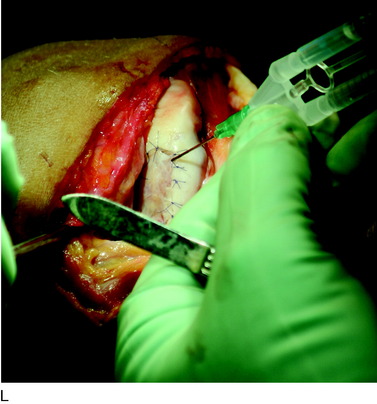

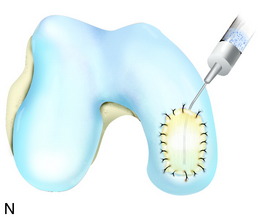

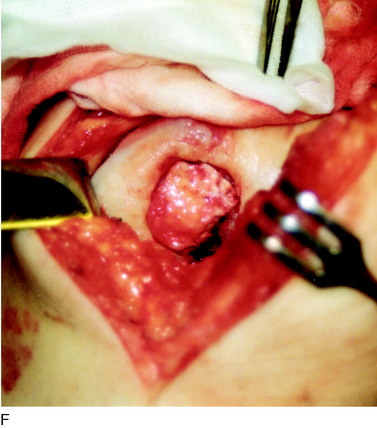

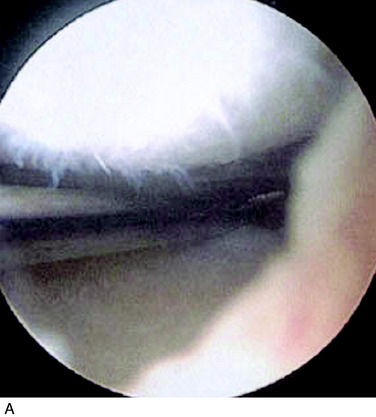

The flap is sutured to the cartilage rim of the defect at the level of the surrounding cartilage and the periosteum-cartilage border is sealed with fibrin glue. A gentle saline injection under the flap reveals any leakage along the cartilage rim, which must be sealed. After aspiration of the saline, the cultured chondrocytes are injected underneath the periosteal cover and the injection site is sutured and sealed (Fig. 35-3). The arthrotomy is closed in separate layers. Bandaging including the foot, lower leg, and knee is applied.

Concomitant Stabilizing Procedures

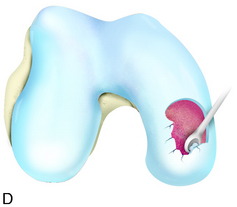

Patellofemoral lesions are often related to an unstable patella, and the patella must thus be stabilized for good healing. Stabilizing procedures may include anteromedialization of the tibial tuberosity and sometimes slight distalization owing to patella alta, lateral release, proximal medial soft tissue (medial patellofemoral ligament and vastus medialis obliquus) shortening, and trochlear groove plasty21 (if the patella is dysplastic) (Fig. 35-4).

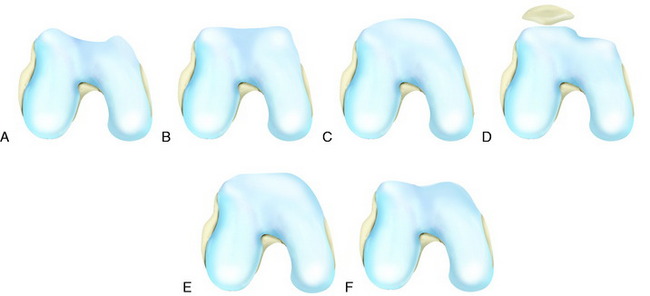

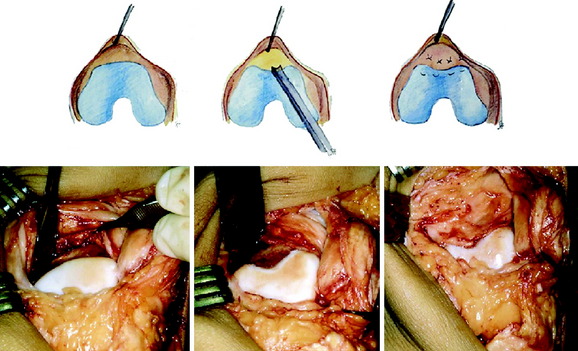

Patellofemoral (trochlear) lesions are often related to patellar instability. If a 6-month training program does not restore functional stability, the background factors present must be corrected. These factors are increased Q-angle (>15°–20°), patella alta, ligament instability (medial patellofemoral ligament [MPFL]), muscular imbalance (musculus vastus medialis obliquus [VMO] weakness) and trochlear dysplasia (flat, convex, and extended in a proximal direction or a flat articulating lateral trochlea) (Fig. 35-5).

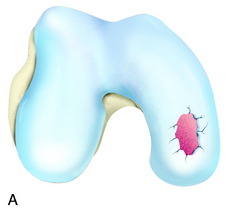

The trochlea groove plasty is performed to establish the skeletal stability of the patella in the trochlea groove in the first 0° to 30° of flexion when the patella is skeletally unstable. Release the synovial membrane from the proximal attachment to the trochlear articular cartilage with a knife. Dissect the membrane free from the femur. Take a curved osteotome and remove the cartilage and bone starting in the center, aiming to the top of the intercondylar notch. Extend 8 to 10 mm distal to the horizontal of the trochlear articular cartilage and widen the groove 15 mm medial and lateral to the center, for a total of approximately 30 mm. If the cortical femoral bone is flat or convex, continue the removal of the bone proximally. Reattach the synovial membrane to the articular cartilage using mattress sutures starting in the synovial edge, cutting through the edge surface 5 to 6 mm into the cartilage. Then, proceed transversely and return the suture through the articular cartilage and the synovial membrane. Adapt the synovial membrane to the cut edge of the articular surface. A maximum of three to five sutures should be used. Inject a layer of fibrin glue under the membrane and compress with a dry sponge for 60 to 120 seconds. Check the sliding of the patella in the new groove and adjust the edges when necessary. This technique preserves the congruity between the trochlea and the patella during the remaining flexion. The author does not address the patella dysplastic forms at any time (Fig. 35-6).

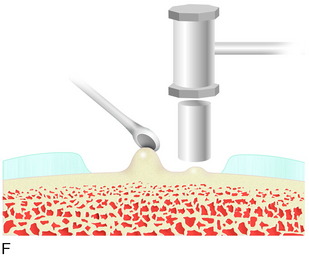

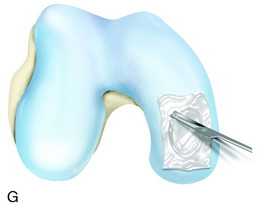

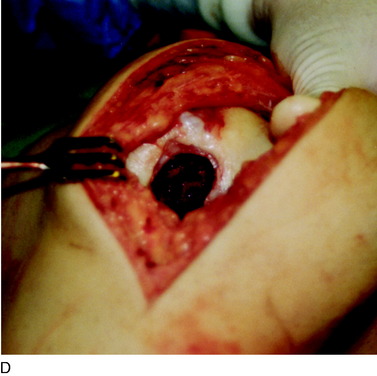

Concomitant Bone Grafting

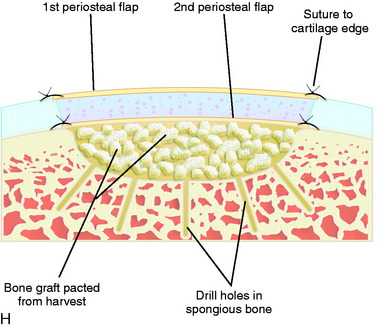

When treating osteochondral lesions with bone defects and pathologic bone deeper than 6 to 7 mm, ACI is not enough and staged or concomitant autologous bone grafting is required. A staged procedure is preferable when both bone grafting and high tibial osteotomy are required. This can then be done concomitantly with the cartilage harvesting. Start by abrading away the sclerotic bottom of the defect and all pathologic bone down to spongy bone and undercut the subchondral bone plate. Use a 2-mm burr and drill holes into the spongy bone. Débride the cartilage to healthy cartilage with vertical edges. Then, harvest the cancellous bone used for grafting the bony defect. If the bony defect is small, use bone from the tibia or femoral condyle; if the defect is larger, harvest the bone from the iliac crest. Pack the bone from the bottom up and contour the bone graft just below the subchondral bone plate. Harvest a periosteal flap to cover the bone graft at the level of the subchondral bone plate, the cambium layer facing the joint. Anchor the graft with horizontal sutures into the cartilage and inject fibrin glue under the flap for fixation to the bone graft. Use a dry sponge to compress the area for 2 to 3 minutes. This will avoid bleeding into the cartilage defect. When required, use bone sutures through small 1.2-mm drill holes or resorbable microanchors (Mitec). Harvest another periosteal flap and suture to the cartilage edges, with the cambium layer facing the defect. Use fibrin glue to seal off the intervals between the sutures. Test the watertightness with a gentle saline injection. If there is no leakage, aspirate the saline and inject the chondrocytes. Close the last opening and seal with fibrin glue (Fig. 35-7).

REHABILITATION

Return to professional athletic training and competition should be judged on an individual basis, including assessment of ROM, muscle strength and endurance, and arthroscopic evaluation and probing/indentation test of the repair area (Fig. 35-8).

AUTHOR’S EVIDENCE-BASED CLINICAL OUTCOMES

Subjective

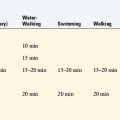

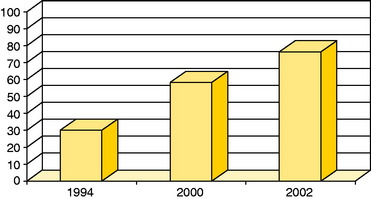

A clinical evaluation at an intermediate to long-term follow-up of the first 101 patients showed that overall, 77% were considered a good or excellent result.22 The patients were divided into groups according to the location and type of the lesion as well as concomitant ACL reconstruction. In the isolated femoral condyle group, 92% were clinically graded as good or excellent; in the OCD group, 89% were in this category; and in the femoral condyle with ACL reconstruction, 75% were in this category. Patients with multiple lesions had a 67% good or excellent rate. The patellar lesions were often treated with concomitant transfer of the tibial tubercle, medial patellofemoral ligament and VMO shortening, and trochlea groove plasty. At follow-up, 65% had a good or excellent result22 compared with 28% in the initial follow-up study.2

An early consecutive cohort of 61 patients were followed for a mean of 7.4 years (range, 5–11 years).20 At the 2-year follow-up, 50 patients had a good or excellent clinical result; at the 5-to 11-year follow-up, 51 patients were considered good or excellent.

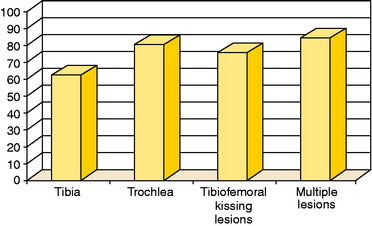

In a study published in 2003,23 58 patients with OCD were treated with ACI and followed an average of 5.6 years. The average age was 26.4 years, and the average defect size was 5.7 cm2, with a maximum defect of 12 cm2. Forty-eight patients had had a mean of 2.1 previous operations because of the injury. The modified Cincinnati clinical rating score was 2.0 points preoperatively and 9.8 points at follow-up. The overall clinical grading was excellent in 53%, good in 38%, fair in 7%, and poor in 2%. Self-assessed improvement was 93%23 (Figs. 35-9 to 35-12). At the ICRS meeting in Toronto in 2002,3 results were presented for patients treated with ACI for cartilage lesions on tibia and trochlea as well as tibiofemoral kissing lesions and multiple lesions (Fig. 35-13).

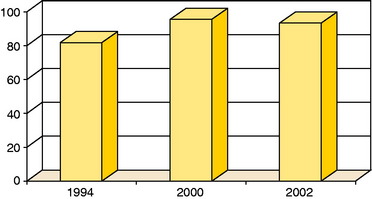

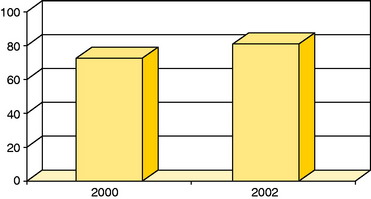

Figure 35-10 Good or excellent results in patients with ACI to femoral condyle lesions and concomitant anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in studies published in 2000 (n = 16)22 and 2002 (n = 11).20

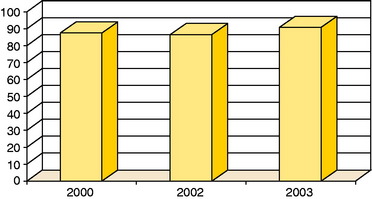

Figure 35-11 Good or excellent results in patients with osteochondritis dessicans (OCD) in studies published in 2000 (n = 18),22 2002 (n = 14),20 and 2003 (n = 58).23

Figure 35-12 Good or excellent results in patients with patella lesions in studies published in 1994 (n = 7),2 2000 (n = 19), and 2002 (n = 17).20

Objective

Different objective tools have been used to evaluate the repair after ACI of chondral and osteochondral lesions including arthroscopic macroscopic assessment and indentation tests as well as repair tissue biopsy for histology and histochemistry. In the first 101 patients, 37 biopsies from the repair tissue were assessed for collagen type II.22 There was correlation between hyaline-like repair tissue and good or excellent clinical outcomes.

In the 61-patient cohort, biopsies from the repair tissue were obtained in 12 patients.20 Eight of the biopsies were characterized as hyaline-like by Safranin O staining and homogeneous appearance under polarized light. Eight hyaline-like and 3 fibrous biopsies stained positive to aggrecan and cartilage oligomeric matrix protein. Hyaline-like biopsies stained positive for collagen type II and fibrous biopsies stained positive for collagen type I. All histologic evaluations were performed by independent scientists.20

An arthroscopic indentation probe was used to measure the stiffness of the repair tissue in 11 of the 61 patients at a mean of 54.3 months (range, 33–84 mo).20 The mean stiffness of repair tissue characterized as hyaline-like by histologic evaluation was 3.0 ± 1.1 N, compared with 1.5 ± 0.35 N of fibrous repair tissue. Good and excellent clinical results correlated with hyaline-like repair tissue, whereas fair or poor clinical results correlated with fibrous repair tissue.20

Vasara and associates26 arthroscopically measured the stiffness of the repair tissue 8 to 18 months after ACI using an indentation probe, and compared it with the stiffness of normal surrounding cartilage. The mean stiffness of the repair tissue was 2.04 ± 0.83 N, and the mean stiffness of the surrounding cartilage was 3.58 ± 1.04 N. Non-OCD repair tissue was stiffer (2.37 ± 0.72 N) than the repair tissue of OCD defects (1.45 ± 0.46 N).26

Functional

In the study of the first 101 consecutive patients with chondral or osteochondral lesions of the knee treated with ACI, the activity levels of the patients were evaluated.22 According to the Tegner/Wallgren score, the patients were able to resume an active lifestyle that included sports with high demands on the knee (e.g., soccer). The modified Cincinnati score was an average 9 out of 10, indicating the patients returned to high-level sports.22

In one study, 45 soccer players treated with ACI were followed for a mean of 40 months.16 Eighty-three percent of the young players below 26 years of age, high–skill-level players, and players operated within 12 months after trauma returned to preinjury levels. The time to return from surgery to soccer was 12 to 18 months.16

Twenty adolescent athletes were followed for a mean of 47 months after ACI.15 At follow-up, the 0 to 10 Tegner activity score had increased from 4 to 8 points, and 96% of patients had returned to impact sports, 60% at the same or higher level than before the injury. Treatment with ACI within 12 months from injury lead to 100% return to preinjury sport, whereas 42% of the chronic cases returned to preinjury sport.15

OUTCOMES FROM OTHER AUTHORS

Gillogly6–8 evaluated 112 patients 2 to 5 years after ACI. The locations of the lesions were diverse and included 15 lesions on the patella, 27 on the trochlea, and multiple lesions in 22. When using the clinician evaluation portion of the modified Cincinnati scale, 93% were considered good or excellent. Using the patient evaluation portion, 89% considered themselves good or excellent.

Minas14 reported on 130 patients treated with ACI in the patellofemoral joint with a follow-up of 2 to 9 years. In a patient satisfaction survey, 80% rated themselves as good or excellent.

Bentley and colleagues1 compared ACI and mosaicplasty in a randomized, prospective study of 100 consecutive patients (58 ACI and 42 mosaicplasty) with a follow-up mean of 19 months. Functional assessment using the modified Cincinnati and Stanmore rating systems as well as clinical assessment showed good or excellent results in 88% after ACI and 69% after mosaicplasty. Arthroscopic assessment 1 year after treatment showed good or excellent repair in 82% after ACI and 34% after mosaicplasty.

In another study, Knutsen and coworkers13 reported on 80 patients with single symptomatic cartilage defects on the femoral condyle treated with either ACI (N = 40) or microfracture (N = 40). Ten patients in each group were treated at four different hospitals. At the 2-year follow-up, both groups had significant clinical improvement. However, according to the Short-Form 36-item questionnaire (SF-36) physical component score, the improvement in the patients treated with microfracture was significantly better than in the ACI group. Three failures were reported, 2 in the ACI group and 1 in the microfracture group. Biopsies from the repair tissue were taken arthroscopically in 67 patients. In the ACI group, 72% of the biopsies showed hyaline-like tissue and 25% showed a mix of hyaline and fibrocartilage. Only 3% showed fibrocartilage. In the biopsies from the microfracture group, 40% were identified as hyaline-like, 29% were a mix of hyaline and fibrocartilage, and 31% contained fibrocartilage.13

Henderson and associates9,10 evaluated 53 patients (72 lesions) with MRI 3 months, 12 months, and 2 years after ACI. The 3-month MRI demonstrated a filling of the defect of at least 50% in 75.3% of the lesions, 46.3% had a near-normal signal, 68.1% had mild or no effusion, and 66.7% had mild or no underlying bone marrow edema. At 12 months, 94.2% had at least 50% defect fill with 86.9% demonstrating a near-normal signal. By 2 years, 97% had at least 50% defect fill with 97% had a near-normal signal. The values for mild or no effusion and mild or no bone marrow edema increased to 91.3% and 88.4%, respectively, at 12 months and 95.6% and 92.6%, respectively, at 2 years. A clinical evaluation of the patients and results from second-look arthroscopy and repair tissue biopsy correlated well with the 12-month MRI.9,10

Brown and colleagues4 evaluated 180 MRIs of 112 patients treated with cartilage resurfacing techniques, including microfracture (MRI done a mean of 15 mo) and ACI (MRI done a mean of 13 mo). Lesions treated with ACI showed better filling of the defect, but graft hypertrophy was present in 63%. The repair tissue after microfracture was depressed compared with the native cartilage and had a propensity for bone development and loss of adjacent cartilage.4

PREVENTION AND MANAGEMENT OF COMPLICATIONS

Local Complications: Periosteal

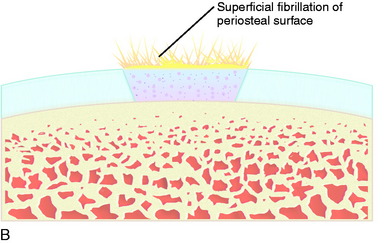

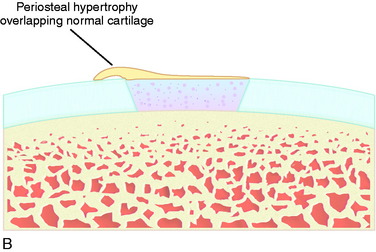

Superficial fibrillation of the periosteal surface that causes crepitus has occurred (Fig. 35-14). Periosteal hypertrophy overlapping the surrounding normal cartilage may cause symptoms of clicking, catching, or crepitus (Fig. 35-15). This complication may appear between 3 and 9 months postoperatively and, in most patients, disappears spontaneously during continued rehabilitation. When this problem interferes with the rehabilitation, it is first handled with change and modification of the rehabilitation program and then with gentle arthroscopic resection. The frequency of periosteal complications was initially reported to be about 25%. By improved surgical technique and adapted rehabilitation, the incidence of this problem has been reduced to 5% to 8%. Other authors have reported frequencies between 5% and 65%.

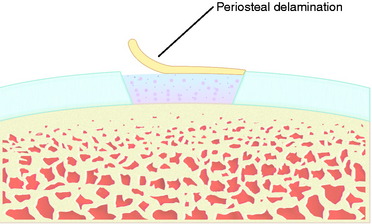

Periosteal delamination has occurred in a few cases (Fig. 35-16). The delamination can be marginal, partial, or total. In a marginal delamination, the periosteal flap is avulsed from the surrounding cartilage up to 10 mm and should be excised or gently débrided. In a partial delamination, the periosteal flap is partly separated from the underlying repair tissue and can be removed by shaving or excising the superficial periosteal delamination. A total periosteal delamination can either be detached or appear as a loose body. It should be removed from the joint or the transplanted area. Usually, the repair tissue will continue filling the defect and motion will stimulate it to produce a new sliding surface. During the 6 to 8 weeks after periosteum removal, ROM training and bicycling with low resistance should be performed, but no running is permitted. Periosteal complications are benign and, when adequately addressed, will have no impact on the end result.

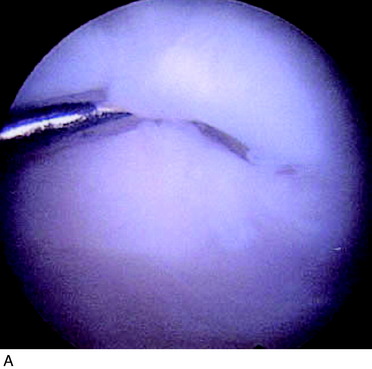

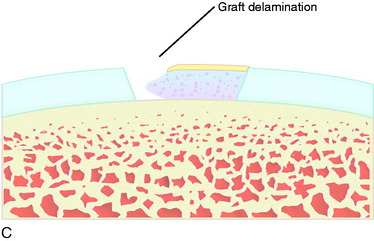

Local Complications: Graft Delamination

Separation and delamination of the total repair tissue down to the subchondral bone is a rare complication (Fig. 35-17). In a marginal graft delamination of less than 10 mm, the area is débrided and left alone. If any bone is visible, the bone is microfractured to create a fibrous repair filling, which will stabilize the area. In a partial graft delamination, the defect is excised and new cartilage is harvested for retransplantation of chondrocytes. In smaller defects up to 1.5 cm2, osteochondral cylinders or microfracture may be first options. In a total graft delamination, it either is detached in a small area or appears as a loose body. A loose body is removed and a delaminated graft excised. New cartilage is harvested for reoperation with ACI. Good results can be achieved after a second ACI procedure.

1 Bentley G., Biant L.C., Carrington R.W., et al. A prospective, randomized comparison of autologous chondrocyte implantation versus mosaicplasty for osteochondral defects in the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:223-230.

2 Brittberg M., Lindahl A., Nilsson A., et al. Treatment of deep cartilage defects in the knee with autologous chondrocyte transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:889-895.

3 Brittberg M., Peterson L., Björnum S., Lindahl A. Multiple lesions in the knee treated with autologous chondrocyte implantation. Toronto, Canada: Read at the meeting of the International Cartilage Repair Society, June 14-18, 2002.

4 Brown W.E., Potter H.G., Marx R.G., et al. Magnetic resonance imaging appearance of cartilage repair in the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;422:214-223.

5 Curl W.W., Krome J., Gordon E.S., et al. Cartilage injuries: a review of 31,516 knee arthroscopies. Arthroscopy. 1997;13:456-460.

6 Gillogly S.D. Clinical results of autologous chondrocyte implantation for large full-thickness chondral defects of the knee: 5-year experience with 112 consecutive patients. Keystone, CO: Read at the annual meeting of the American Society for Sports Medicine, June 2001.

7 Gillogly S.D. Autologuos chondrocyte implantation: complex defects and concomitant procedures. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2002;10:120-128.

8 Gillogly S.D. Treatment of large full-thickness chondral defects of the knee with autologous chondrocyte implantation. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(suppl 1):147-153.

9 Henderson I.J., Tuy B., Connell D., et al. Prospective clinical study of autologous chondrocyte implantation and correlation with MRI at 3 and 12 months. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:1060-1066.

10 Henderson I.J., Tuy B., Connell D., et al. Autologous chondrocyte implantation for treatment of focal chondral defects of the knee—a clinical, arthroscopic, MRI and histologic evaluation at 2 years. Knee. 2005;12:209-216.

11 Hjelle K., Solheim E., Strand T., et al. Articular cartilage defects in 1000 knee arthroscopies. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:730-734.

12 Johnson D.L., Urban W.P.Jr., Caborn D.N., et al. Articular cartilage changes seen with magnetic resonance imaging–detected bone bruises associated with acute anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:409-414.

13 Knutsen G., Engebretsen L., Ludvigsen T.C., et al. Autologous chondrocyte implantation compared with microfracture in the knee. A randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:455-464.

14 Minas T. A surgical algorithm for the management of patellofemoral disease. Philadelphia, PA: Read at the meeting Advanced Concepts in ACI, November 2007.

15 Mithöfer K., Minas T., Peterson L., et al. Functional outcome of knee articular cartilage repair in adolescent athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1147-1153.

16 Mithöfer K., Peterson L., Mandelbaum B.R., Minas T. Articular cartilage repair in soccer players with autologous chondrocyte transplantation: functional outcome and return to competition. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1639-1646.

17 Noyes F.R., Barber-Westin S.D., Butler D.L., Wilkins R.M. The role of allografts in repair and reconstruction of knee joint ligaments and menisci. Cannon W.D.Jr., editor. Instructional Course Lectures. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1998;Vol. 47:379-396.

18 Noyes F.R., Bassett R.W., Grood E.S., Butler D.L. Arthroscopy in acute traumatic hemarthrosis of the knee: incidence of anterior cruciate tears and other injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:687-695.

19 Noyes F.R., Mooar P.A., Matthews D.S., Butler D.L. The symptomatic anterior cruciate–deficient knee: part I. The long-term functional disability in athletically active individuals. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:154-162.

20 Peterson L., Brittberg M., Kiviranta I., et al. Autologous chondrocyte transplantation: biomechanics and long-term durability. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:2-12.

21 Peterson L., Karlsson J., Brittberg M. Patellar instability with recurrent dislocation due to patellofemoral dysplasia. Results after surgical treatment. Bull Hosp Jt Dis Orthop Inst. 1988;48:130-139.

22 Peterson L., Minas T., Brittberg M., et al. Two- to 9-year outcome after autologous chondrocyte transplantation of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;374:212-234.

23 Peterson L., Minas T., Brittberg M., Lindahl A. Treatment of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee with autologous chondrocyte transplantation: results at two to ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(suppl 2):17-25.

24 Shelbourne K.D., Jari S., Gray T. Outcome of untreated traumatic articular cartilage defects of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(suppl 2):8-16.

25 Schimmer R.C., Brülhart K.B., Duff C., Glinz W. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy: a 12-year follow-up and two-step evaluation of the long-term course. Arthroscopy. 1998;14:136-142.

26 Vasara A.I., Nieminen M.T., Jurvelin J.S., et al. Indentation stiffness of repair tissue after autologous chondrocyte transplantation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;433:233-242.