Chapter 93 Autograft Choice in Anterior: Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Should It Be Patellar Tendon or Hamstring Tendon?

The optimal graft choice for reconstruction of the deficient anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) remains controversial. Graft options currently in use include autogenous or autologous patellar tendon, ipsilateral patellar tendon, hamstring tendons (double or quadruple strand), quadriceps tendon (with or without patellar bone), xenografts, and synthetic replacements or augmentations. Autograft tissue currently is the most common source for grafts worldwide, with the main choices being the patellar tendon and hamstring tendons (semitendinosus and gracilis). The advantages and disadvantages of both these popular autografts have been discussed extensively in the literature. Both the quadruple-strand hamstring and bone patellar tendon grafts have demonstrated more than adequate load to failure and single pull strengths with multiple fixation configurations when biomechanically compared with native ACLs.1–3 Patellar tendon grafts have traditionally been favored for their robust strength, relative ease of operative fixation, and the potential for bone-to-bone ingrowth after implantation. Hamstring tendons are a relatively newer graft choice and have become popular for the relative ease and low morbidity of their harvest.

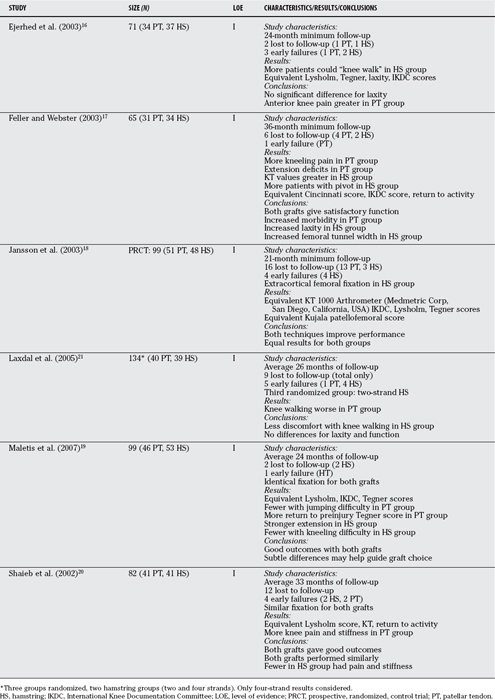

Eighteen studies were identified by the search criteria as prospective, randomized comparisons with patients being allocated to receive one of the two specified autografts. Seven of these were subsequently excluded because group assignment was not specified as being strictly by random allocation (birth date/year randomization was accepted, however, because this did not have the potential for manipulation).4–10 Three investigations were further eliminated because they used two-strand hamstring grafts (versus four).11–13 One investigation reported outcome data recorded at 12 months (vs. 24 months).14 Another study utilized a novel hamstring graft preparation (including a bone block) that was not believed to be a standard technique.15 The remaining six investigations met the full criteria for eligibility and were included in the final analysis.16–21

TECHNICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The majority of the studies used “aperture fixation” with interference screws for graft fixation on both the femoral and tibial sides of the joint. Metal screws were the preferred fixation for both grafts in the earlier studies, with a trend to bioabsorbable screws for fixation of soft-tissue grafts in more recent investigations. Two studies used extracortical fixation with either plate or endobutton (Smith & Nephew, Andover, Massachusetts, USA) fixation on the femoral side for hamstring grafts.17,18 Maletis and coworkers19 used bioabsorbable screws on both the femoral and tibial sides; this is the only study to use identical fixation for both grafts. None of the studies specified the tension at which the grafts were fixed. The flexion angle of the knee at the time of fixation was inconsistently reported and varied from hyperextension to up to 70 degrees of flexion. Rehabilitation protocols were similar, as were follow-up schedules.

CLINICAL OUTCOMES

Strength and range of motion were inconsistently reported among the studies. Although early follow-up (<1 year) often demonstrated strength differences, no consistent trends were noted across the studies for either graft in terms of flexion and extension strength at 2 years after reconstruction. Maletis and coworkers19 found persistent flexion weakness in the hamstring group and persistent quadriceps weakness in the patellar tendon group, but the deficits were small and of uncertain clinical significance. Similarly, although extension deficits were seen early in the BPTB group in several studies, the groups usually equilibrated at 2-year follow-up. In 2 studies, the extension deficit persisted.17,20

Two studies demonstrated a statistically significant proportion of patients in the hamstring group with an abnormal pivot shift examination at final follow-up.17,19 The severity of the pivot shift (i.e., a “glide” vs. an overt subluxation) was specified in only 1 study, and no patients demonstrated more than a grade 1 (glide).19 No differences were found between the grafts with respect to the one-leg hop test in the studies that reported this outcome.

FUNCTIONAL OUTCOMES

None of the investigations used a validated measure of health-related quality of life. The majority of the studies reported activity ratings and clinical composite measures that included some index of patient satisfaction. One study included the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), a generic measure of health-related quality of life, as part of the postoperative assessment.19 A significant increase in physical function occurred between years 1 and 2 after ACL reconstruction in both groups. No differences were demonstrated between the grafts at 2 years.

The Lysholm score is a 100-point scoring system for examining a patient’s knee-specific symptoms including mechanical locking, instability, pain, swelling, stair climbing, and squatting.22 Lysholm scores were used to assess outcome in 5 of the 6 studies. Significant improvement was found from preoperative to postoperative scores in all of these studies. No significant differences were noted in the Lysholm scores between the 2 grafts. Similarly, Tegner scores, a patient-reported measure of activity level, improved from preoperative to postoperative assessments in five studies and did not show a statistical difference between the grafts at final assessment. In 1 study, more patients were able to return to their preoperative activity level with a BPTB graft.19

COMPLICATIONS

Septic joint infections were rare with five reported from the six investigations (1%). Three cases resolved with arthroscopic lavage, administration of intravenous antibiotics, and retention of the original graft. In two cases, a staged revision reconstruction was necessary. No difference was seen in the rate of deep infection for the two grafts. Superficial infections were inconsistently reported, as were the rates of deep venous thrombosis, pretibial numbness, and arthro-fibrosis.

DISCUSSION

Utilizing only Level I, strictly randomized data, researchers found no major differences between the two grafts with respect to laxity, patient-assessed outcomes, or subjective scores (Table 93-1). The finding of a persistent pivot shift in a greater proportion of patients with hamstring reconstruction in 2 studies is an important observation. Both anterior knee pain and kneeling pain were experienced by more patients after BPTB grafts in all studies. The trials were international, including 4 Scandinavian, 2 American, and 1 Australian trial. The study group was young, active, and predominantly male. This would be consistent with the average patient requesting ACL reconstruction in the North American population.

In summarizing existing evidence, limitations are introduced by the heterogeneity and quality of the individual studies. In terms of heterogeneity, although the individual study designs and sample populations were similar—all were randomized trials conducted in young, active, predominantly male populations—the technical aspects of graft harvest, fixation, and tensioning were variable and may have introduced potentially important differences in graft survival and function at 2 years. Variations in epidemiologic quality among the individual trials might have led to overestimation or underestimation of treatment effects. Publication bias might have played a role in the original literature search because only 1 foreign language study was identified.8

Several previous reviews have been previously published comparing these 2 grafts with inconsistent findings. A “review of reviews” was undertaken by Poolman and coworkers23 to investigate the reasons for the discordant findings. Eleven such reviews were identified in that investigation, with 3 favoring the patellar tendon graft for stability and 6 favoring the hamstring graft to prevent anterior knee pain. The quality of the individual reviews was highly variable and believed to be the most significant reason for the differences in their findings.

This brief narrative review is intended to provide the surgeon with up-to-date data, which can be used to appropriately educate his or her patients in the consent process before ACL reconstruction. Furthermore, this work represents the beginnings of a more extensive analysis that will appear in the Cochrane database. A wealth of data can be derived from this sample of Level I randomized trials on ACL reconstruction. Further inference may be possible with the raw data from each study and/or a formal meta-analysis as per the Cochrane database methodology. The Cochrane review will attempt to provide overall estimates of treatment effect via statistical pooling of study data. Definitive information, however, can come only from a large randomized trial with long-term functional data as a primary end point. Table 93-2 provides a summary of recommendations.

| STATEMENT | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE | GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|---|

1 Noyes FR, Butler DL, Grood ES, et al. Biomechanical analysis of human ligament grafts used in knee-ligament repairs and reconstructions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66A:344-352.

2 Woo SL, Kanamori A, Zeminski J, et al. The effectiveness of reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament with hamstrings and patellar tendon. A cadaveric study comparing anterior tibial and rotational loads. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:907-914.

3 Woo SL, Chan SS, Yamaji T. Biomechanics of knee ligament healing, repair and reconstruction. J Biomech. 1997;30:431-439.

4 Aglietti P, Giron F, Buzzi R, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Bone-patellar tendon-bone compared with double semitendinosus and gracilis tendon grafts. A prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:2143-2155.

5 Aglietti P, Buzzi R, De Biase P, Zacherotti G. A comparison between patellar tendon and doubled semitendonosis/ gracilis for ACL reconstruction: A minimum 5 year follow up. J Sports Traumatol Rel Res. 1997;19:57-68.

6 Aune AK, Holm I, Risberg MA, et al. Four-strand hamstring tendon autograft compared with patellar tendon-bone autograft for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction—a randomized study with two-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:722-728.

7 Eriksson K, Anderberg P, Hamberg P, et al. A comparison of quadruple semitendinosus and patellar tendon grafts in reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83-B:348-354.

8 Ropke M, Becker R, Urbach D, Nebelung W. Semitendinosus tendon vs patellar ligament—clinical results after reconstruction of the ACL. Unfallchirurg. 2001;104:312-316.

9 Sajovic M, Vengust V, Komadina R, et al. A prospective, randomized comparison of semitendinosus and gracilis tendon versus patellar tendon autografts for ACL reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1933-1940.

10 Zaffagnini S, Maracci M, Lo Presti M, et al. Prospective and randomized evaluation of ACL reconstruction with three techniques: A clinical and radiographic evaluation at five years follow up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol. 2006;14:1060-1069.

11 Anderson AF, Snyder RB, Lipscomb AB. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction—a prospective randomized study of three surgical methods. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:272-279.

12 Beynnon B, Johnson RJ, Fleming BC, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament replacement: Comparison of bone-patellar tendon-bone grafts with two-strand hamstring grafts. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:1503-1513.

13 O’Neill DB. Arthroscopically assisted reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: A prospective randomized analysis of three techniques. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:803-813.

14 Beard DJ, Anderson JL, Davies S, et al. Hamstrings versus patellar tendon for ACL reconstruction: A randomized controlled trial. Knee. 2001;8:45-50.

15 Matsumoto A, Yoshiya S, Muratsu M, et al. A comparison of bone patellar tendon bone and bone hamstring bone autografts for ACL reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:213-219.

16 Ejerhed L, Kartus J, Sernert N, et al. Patellar tendon or semitendinosus tendon autografts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? A prospective randomized study with a two-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:19-25.

17 Feller JA, Webster KE. A randomized comparison of patellar tendon and hamstring tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:564-573.

18 Jansson KA, Linko E, Sandelin J, Harilainen A. A Prospective randomized study of patellar versus hamstring tendon autografts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:12-18.

19 Maletis GB, Cameron SL, Tengan JJ, et al. A prospective randomized study of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A comparison of patellar tendon and quadruple strand semitendonosis/gracilis tendons fixed with bioabsorbable interference screws. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:385-394.

20 Shaieb MD, Kan DM, Chang S, et al. A prospective randomized comparison of patellar tendon versus semitendinosus and gracilis tendon autografts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:214-220.

21 Laxdal G, Kartus J, Hansson L, et al. A prospective randomized comparison of bone patellar tendon bone and hamstring grafts for ACL reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:34-42.

22 Lysholm J, Gilquist J. Evaluation of knee ligament surgery results with special emphasis on the use of a scoring scale. Am J Sports Med. 1982;10:150-153.

23 Poolman RW, Aboulai JAK, Conter HJ, Bhandari M. Overlapping systematic reviews of ACL reconstruction comparing hamstring autograft with bone patellar tendon bone autograft: Why are they different? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1542-1552.