Chapter 15 Augmentation of Facial Structures with Autologous Fat

Introduction

With renewed interest in volumetric enhancement for facial rejuvenation, fat grafting is once again gaining popularity. It has been used successfully for soft tissue augmentation since 18931 and in 1909 Eugene Hollander described a technique to transplant fat using a needle and syringe.2 In 1926 Miller claimed that grafting fat through hollow metal cannulas gave a more natural and longer lasting correction than paraffin.3 Soon after the introduction of suction curettage of body fat for contouring, Teimourian and Illouz described the injection of semi-liquid fat into liposuction deformities4,5 and Chajchir described injecting suctioned fat into the face.6 Although some of the initial results were positive7,8 many were not.9,10 Illouz compared the longevity of grafted fat in the face to that of collagen.4 In the 1980s, many well-respected plastic surgeons denounced fat grafting based on negative results.11,12 As techniques changed, more positive results were obtained and surgeons began to realize that grafted fat could result in long-lasting contour changes.13–16 The technique developed by Coleman began in 1987 and evolved over the next few years to become a standard for fat grafting. It emphasizes basic sound surgical techniques with the gentle handling of tissues to make fat grafting predictable and reliable.

Indications and Contraindications

Fat Grafting For Facial Rejuvenation

The cheek is a relatively easy area to visualize in three dimensions. The immediate, intraoperative results of cheek augmentation with fat are the most similar to what will be seen as the final result.17 This is a good area to begin learning and practicing making three-dimensional changes in the face. On the other hand, the lower eyelid is one of the most difficult areas for structural fat grafting. Irregularities, lumps, and excess fat can easily be seen through the thin eyelid skin when the swelling resolves. The lower eyelid should be approached with caution and only after gaining confidence in other more forgiving areas of the face.

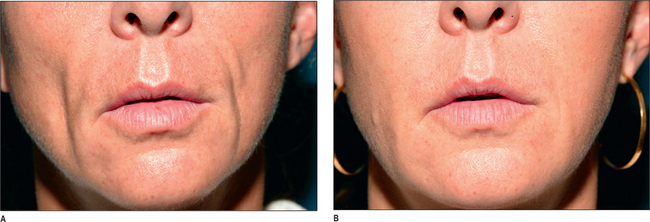

The lower lip has a slightly protuberant rim, which is less distinctive than the white roll of the upper lip. The fullness and depressions of an attractive lower lip are opposite to those of the upper lip, with a central cleft and more fullness laterally. The amount of vermilion visible is much greater in the lower lip than in the upper lip (Fig. 15.1).18,19

Fat Grafting for Change in Facial Proportion

Augmentation of the chin is accomplished by first placing fat over the entire anterior prominence of the mandible.20 The shape of the chin is then sculpted by placing additional fat in two small balls, leaving a slight central cleft between them. This creates not only a more prominent chin, but also a shapelier chin.

Mandibular augmentation creates a defined border separating the face from the neck. This is generally considered an attractive look and can be created by placing fat deep along the periosteum of the mandible as well as more superficially beneath the skin. The angle of the mandible should be identified and emphasized if it is not visible. A continuous line should then be developed from the angle to the chin (Fig. 15.2).

Fat Grafting for Reconstruction

Fat can be placed deep along the facial bones as well as more superficially beneath the skin to correct many apparent deficiencies of both bone and soft tissue. It has been used successfully to correct defects such as hemifacial microsomia and atrophy, post-traumatic defects, and post-surgical defects.21 Tissue lost after radical neck dissections can be supplemented with fat grafting to restore a normal facial appearance. In addition, the flattening of the posterior jaw line created by most facelift procedures can be corrected using fat grafts (Fig. 15.3).

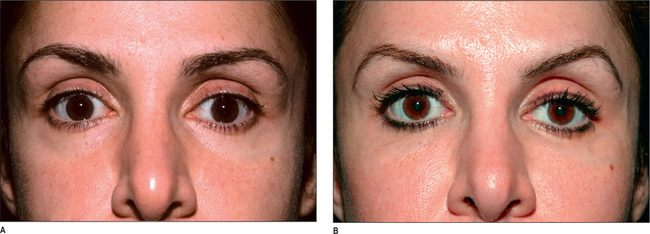

Fat Grafting for Lipoatrophy

There is a typical pattern of facial fat loss that occurs in patients who are HIV positive and who receive certain anti-retroviral medications. Unlike generalized aging, this loss of fat generally occurs in the buccal cheeks and is a characteristic of the disease. In addition, these patients may have loss of fat in the temples and in the periorbital region. All of these areas can be addressed with fat grafting to restore a healthier appearance to the patient. (Fig. 15.4)22,23

Preoperative History and Considerations

The primary unique consideration for the patient undergoing a fat grafting procedure is the present and future weight of the patient. Patients are ideally at their optimal weight and will not fluctuate significantly from that weight. Since the transferred/grafted fat remains viable, it will respond to weight changes as if it were still in its native site. Patients should understand that if they lose a significant amount of weight they can lose the correction obtained. Alternatively, if they gain a significant amount of weight, the fat placed may increase in volume. Additionally, volume increases have been noted in some patients treated with anti-retroviral medications.

Technique of fat Grafting

Harvesting

The detailed steps regarding harvesting of tissues have been previously described in the literature.24–26 The main objective of the harvesting portion of the procedure is to gently obtain intact tissue parcels that will remain viable during the grafting process. The choice of harvesting sites is based only on the area of desired contour change, as no clear correlation has been made between the harvest site and longevity of grafted fat.27,28 Small incisions are made adjacent to the harvest site and using a blunt lamis infiltrator, the tissue is infiltrated with 0.2% lidocaine with 1 : 200 000 epinephrine. Even when the patient is under general anesthesia, the local infiltration is performed for hemostatic purposes. Approximately 1 cc of anesthetic is infiltrated for each 1 cc of fat to be harvested. Superwet techniques should be avoided to maintain the architecture of the harvested fat. Fat is then harvested using a 10 cc syringe attached to a blunt, two-holed Coleman harvesting cannula. Syringes larger than 10 cc and plunger-locking devices are not used as these may create too much negative pressure and damage the parcels of fat. Instead, minimal negative pressure is created with the 10 cc syringe and the curetting action of the cannula. The most important consideration regarding harvesting of fat is maintaining the integrity of the fat cells and the normal architecture of the tissue. Any mechanical or chemical insult (straining, chopping, beating, washing) that damages this fragile tissue will result in eventual necrosis of the injected fat.

Placement

Depending on the extent of surgery, general, regional or local anesthesia may be used when fat is grafted. For larger body fat grafting cases, general anesthesia is preferred. Incisions for grafting the fat are positioned such that fat can be placed from at least two different directions. A blunt Type I Coleman cannula is used for the placement of the local anesthetic as well as the fat. Sharp needles should be used with extreme care in the subcutaneous planes for injection of local anesthetic and fat due to the risk of intravascular injection.29 The infiltration cannula is attached to a 1 cc Luer-Lok syringe filled with refined tissue and the fat is distributed into the tissue planes only as the cannula is withdrawn. Very small aliquots of fat (0.02-0.1 cc) are placed with each pass of the cannula such that each parcel of fat is surrounded by native tissue to ensure access to a blood supply and stability of the transplanted tissue. The fat should be grafted such that the desired shapes are formed during the infiltration of the fat. Because the fat is integrated into the host tissue, attempts at significant molding of the fat after placement are usually futile and can cause undesirable irregularities.

Fat grafting in the subcutaneous plane, as well as along the periosteum and into the muscle, has been described. The Coleman technique of structural fat grafting, however, does not promote the intentional placement of fat into the muscle, as it appears to cause a thickening of the muscle that is undesirable, especially in the lip. When correcting significant bony or structural deficiencies, it is usually essential to place fat deep along the periosteum and gradually add additional fat more superficially. Placement of fat in the subcutaneous plane gives a more significant volume change than the deeper, supraperiosteal grafts, and placement of fat just beneath the skin can result in an improvement in skin texture over time. Intradermal placement has been discouraged in the past, but has been revisited recently.30 Using a sharp 22-gauge needle attached to a 1 cc syringe of refined fat, small amounts of fat can be placed intradermally into scars and deep wrinkles. The long-term effect of this method of placement does not appear to be as reliable as the subcutaneous placement with a larger bore cannula, however, and is different from the subcision technique described by Carraway.7 Instead of undermining the area first with a sharp needle and then injecting the fat, it is recommended that the fat be placed first, followed by the release of any remaining adhesions or scar tissue using a ‘v-dissector’ or sharp needle afterward.31 This maneuver, however, is traumatic and may destabilize the fat. It should be used with caution and should be delayed until the intradermal and subcutaneous placement is completed.

Complications of fat Grafting

The most devastating and fortunately rare complication is an intravascular embolization.29 This has never occurred when using a blunt cannula. Therefore, sharp needles are discouraged, except when placing fat directly into the dermis. In addition, large boluses of fat should not be injected and injection guns should not be used when grafting fat.

Late complications include infections, which can result in resorption of the grafted fat. Strict sterile technique must be employed and cannulas that penetrate the oral mucosa should be considered contaminated and replaced. If lip augmentation is performed as part of a total facial rejuvenation procedure, it should be performed last. As previously mentioned, an increase or decrease in the size of the grafted area secondary to weight gain or loss can occur. Cosmetic concerns resulting from either too much or too little fat placed in an area as well as lumps and irregularities can occur. With experience, more accurate estimations of the correct volume and more precise placement techniques will be possible. In addition, contour deformities can occur in the donor site areas and incisions can remain visible for a prolonged period. Fat must be harvested carefully to avoid irregularities. Incisions can be lubricated with the oil obtained after centrifugation and/or revised later. This is not a complete list of complications and more exhaustive descriptions of potential complications32 and untoward effects are available.

Postoperative Care

Light touch can be instrumental in reducing swelling by encouraging lymphatic drainage. Deep massage, however, should be avoided in the first weeks after fat grafting. Although it is difficult to move the recently infiltrated fat, strong directed pressure could displace the fat and force it into an undesirable area. Recovery from this procedure usually requires a minimum of 2 weeks and sometimes as long as 6 weeks.32

1. Neuber F. Fettransplantation. Bericht über die Verhandlungen der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Chirurgie Zbl Chir. 1893;22:66.

2. Holländer E. Berliner klinischer. Wochenschrift. 18, 1909.

3. Miller C. Cannula implants and review of implantation techniques in esthetic surgery. Chicago: The Oak Press, 1926.

4. Illouz Y.G. The fat cell ‘graft’: a new technique to fill depressions. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;78(1):122-123.

5. Teimourian B. Repair of soft-tissue contour deficit by means of semiliquid fat graft. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;78(1):123-124.

6. Chajchir A., Benzaquen I. Liposuction fat grafts in face wrinkles and hemifacial atrophy. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1986;10(2):115-117.

7. Carraway J.H., Mellow C.G. Syringe aspiration and fat concentration: a simple technique for autologous fat injection. Ann Plast Surg. 1990;24(3):293-296.

8. Lewis C.M. Transplantation of autologous fat. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;88(6):1110-1111.

9. Ellenbogen R. Invited commentary on autologus fat injection. Ann Plast Surg. 1990;24:297.

10. Ersek R.A. Transplantation of purified autologous fat: a 3-year follow-up is disappointing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87(2):219-227.

11. Goldwyn R.M. Unproven treatment: whose benefit, whose responsibility? Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;81(6):946-947.

12. Fredricks S. Fat grafting injection for soft-tissue augumentation (Discussion). Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;84:935.

13. Ellenbogen R., Motykie G., Youn A., Svehlak S., Yamini D. Facial reshaping using less invasive methods. Aesthetic Surg J. 2005;25(2):144-152.

14. Coleman S.R. Long-term survival of fat transplants: controlled demonstrations. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1995;19(5):421-425.

15. Guerrerosantos J. Long-term outcome of autologous fat transplantation in aesthetic facial recontouring: sixteen years of experience with 1936 cases. Clin Plast Surg. 2000;27(4):515-543.

16. Trepsat F. Periorbital rejuvenation combining fat grafting and blepharoplasties. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2003;27(4):243-253.

17. Coleman S.R. Infraorbital and Cheek Regions Chapter 11. In: Structural fat grafting. St. Louis, MO: Quality Medical Pub; 2004:293-352.

18. Coleman S.R. Lips Chapter 9. In: Structural fat grafting. St. Louis, MO: Quality Medical Pub; 2004:203-236.

19. Coleman S.R. Lipoinfiltration of the upper lip white roll. Aesthetic Surg J. 1994;14(4):231-234.

20. Coleman S.R. Chin and Jawline Chapter 9. In: Structural fat grafting. St. Louis, MO: Quality Medical Pub; 2004:237-270.

21. Coleman S.R. Chapter 16: Revisional fat grafting of the cheek and lower eyelid. In Grotting J.C., editor: Reoperative aesthetic & reconstructive plastic surgery, 2nd ed, St. Louis, MO: Quality Medical Pub, 2006.

22. Burnouf M., Buffet M., Schwarzinger M., et al. Evaluation of Coleman lipostructure for treatment of facial lipoatrophy in patients with human immunodeficiency virus and parameters associated with the efficiency of this technique. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(10):1220-1224.

23. Coleman S.R. Discussion of treatment of facial fat atrophy related to treatment with protease inhibitors by autologous fat injection in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Plast Reconstr Surg. 114(2), 2004.

24. Coleman S. Hand rejuvenation with structural fat grafting. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110(7):1731-1743.

25. Coleman S. Structural fat grafting. St. Louis, MO: Quality Medical Pub, 2004.

26. Coleman S.R. Structural fat grafting. In: Nahai F., editor. The art of aesthetic surgery: principles & techniques. St. Louis, MO: Quality Medical Pub; 2005:289-363.

27. Rohrich R.J., Sorokin E.S., Brown S.A. In search of improved fat transfer viability: a quantitative analysis of the role of centrifugation and harvest site. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(1):391-395.

28. Ullmann Y., Shoshani O., Fodor A., et al. Searching for the favorable donor site for fat injection: in vivo study using the nude mice model. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(10):1304-1307.

29. Coleman S.R. Avoidance of arterial occlusion from injection of soft tissue fillers. Aesthetic Surg J. 2002;22(6):555-557.

30. Coleman S. Facial augmentation with structural fat grafting. Clin Plast Surg. 33(4), 2006.

31. Orentreich D.S., Orentreich N. Subcutaneous incisionless (subcision) surgery for the correction of depressed scars and wrinkles. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21(6):543-549.

32. Coleman S.R. Problems, complications and postprocedure care: chapter 4. In: Structural fat grafting. St. Louis, MO:: Quality Medical Pub; 2004:75-102.