Chapter 34 Atrophic and dystrophic conditions

ATROPHIC CHANGES OF THE INTERNAL GENITAL ORGANS

Vulval atrophy in older women

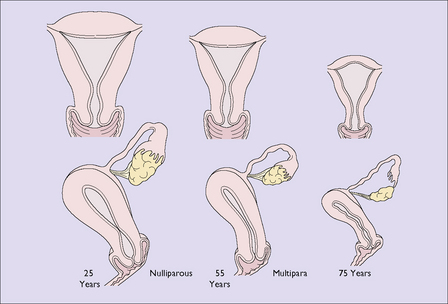

By the time a woman reaches the age of 75 the uterus, the Fallopian tubes and the ovaries have shrunk considerably (Fig. 34.1). In the uterus, the endometrium has become atrophic and the muscle fibres of the myometrium have been progressively replaced by fibrous tissue. The cervix has atrophied and the cervical canal may become obliterated. If the woman develops uterine infection the pus might not escape, leading to a pyometra. This may also occur if the woman develops an endometrial or cervical carcinoma. The woman may complain of lower abdominal pain, and an examination shows that the uterus is larger than expected for her age. The diagnosis is confirmed by ultrasound scanning, which shows that the uterine cavity is enlarged and filled with fluid. If carcinoma is detected it is treated appropriately; if it is not present, the cervix is dilated and a drain inserted for a few days.

The pelvic floor

Deprived of oestrogen, the blood supply to the muscles of the pelvic floor diminishes. The pelvic floor muscles lose their tone and the connective tissue loses its elasticity, with the result that pelvic floor tissues damaged during childbirth are likely to relax, with varying degrees of prolapse (see Ch. 38).

PRURITUS VULVAE (ITCHY VULVA)

There have been a number of attempts to classify the disorders of the vulval epithelium. The most recent is shown in Box 34.1.

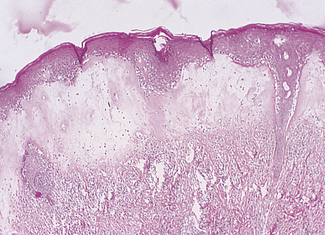

The most common vulval problem is lichen sclerosis, which presents with chronic pruritus, pain and dyspareunia if there is ulceration and fissures. The skin may be reddish or normal in colour, and atrophic shiny white plaques are seen. A skin biopsy shows that the horny layer is unchanged or hyperkeratinized, with thinning of the epidermis and the disappearance of the rete pegs. The dermis is oedematous, with some degree of hyalinization, and collections of round cells are seen (Fig. 34.2).

Squamous hyperplasia

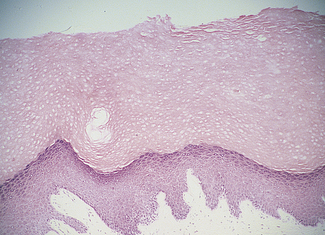

The skin is usually reddened with exaggerated folds. In certain areas lichenified white patches may be seen. A biopsy specimen will show a thickened epithelium, with elongated papillae which retain their normal shape. The dermis is oedematous and contains numbers of plasma cells (Fig. 34.3).

Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) is discussed in Chapter 37.

Aetiology

Studies of women who have pruritus show that this disease has a varied aetiology.

General skin diseases

The conditions listed in Table 34.1 are the usual skin diseases that may manifest as pruritus vulvae. Fungal infections may also cause vulval itch, although the itch is generally intercrural.

| Percentage of Cases | |

|---|---|

| General skin diseases (psoriasis, leucoderma, lichen planus, intertrigo, scabies) |

5 |

| General diseases (diabetes, ? deficiency diseases) |

5 |

| Allergic dermatitis | 5 |

| Vaginal discharges Trichomoniasis Candidiasis |

50 |

| Psychosomatic conditions | 35 |

Treatment

If the itch is severe, a sedative should be prescribed to help the woman sleep at night. Elderly women may obtain relief if hormone replacement treatment (see p. 325) is tried. The patient requires a good deal of support and reassurance over the period of treatment, but should be made aware that, in time, the itch ceases in about 90% of patients.